Abstract

Background

The prevalence of hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening (HALT) and reduced leaflet motion (RLM) is unknown in surgically implanted bioprostheses because systematic investigation of HALT and/or RLM is limited to a few catheter‐based valves. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of HALT and RLM by cardiac computed tomography in patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement and received a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis.

Methods and Results

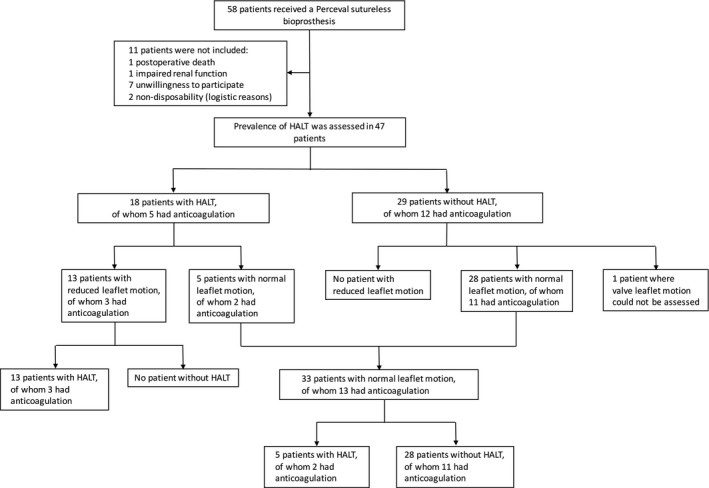

This was a single‐center prospective observational study that included 47 patients (83.5% of the total number of implantations) who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement with implantation of the Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis (LivaNova PLC, London, UK) at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden from 2012 to 2016 and were studied by cardiac computed tomography. Cardiac computed tomography was performed at a median of 491 days (range 36–1247 days) postoperatively. HALT was found in 18 (38%) patients and RLM in 13 (28%) patients. All patients with RLM had HALT. Among patients with HALT, 5 out of 18 patients (28%) were treated with anticoagulation (warfarin or any novel oral anticoagulant) at the time of cardiac computed tomography. Among patients with RLM, 3 out of 13 patients (23%) were treated with anticoagulation.

Conclusions

HALT and RLM were prevalent in the surgically implanted Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Both HALT and RLM were found in patients with ongoing anticoagulation treatment. Whether these findings are associated with adverse events needs further study.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT02671474.

Keywords: aortic valve surgery, bioprosthesis, cardiac computed tomography, leaflet motion, leaflet thickening

Subject Categories: Aortic Valve Replacement/Transcather Aortic Valve Implantation

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Hypo‐attenuated leaflet motion and reduced leaflet motion were prevalent in the surgically implanted Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis.

Both hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening and reduced leaflet motion were found in patients with ongoing anticoagulation treatment.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Whether hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening and reduced leaflet motion in the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis are associated with adverse events is currently unknown and warrants further investigation.

The findings cannot be regarded as recommendations regarding anticoagulation therapy following Perceval sutureless implantation since the study was not designed to investigate this.

Introduction

Recent reports have shown a high prevalence of hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening (HALT) with or without reduced leaflet motion (RLM) detected with cardiac computed tomography (CT) of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) prostheses.1, 2, 3, 4 The prevalence of RLM and HALT has been studied in a small number of different types of surgically implanted bioprostheses.4 Additional data for prosthetic heart valves have been requested by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5 Patients are frequently asymptomatic and the abnormalities have been detected incidentally. Leaflet thrombosis has been speculated to be the underlying cause of HALT and RLM because anticoagulation therapy with warfarin has been associated with a decreased prevalence of RLM. Furthermore, restoration of cusp thickness and leaflet motion has been noted in patients receiving warfarin. Although the clinical consequences of HALT and RLM are still uncertain, left‐sided prosthetic valve thrombosis is a risk factor for stroke,6, 7 and prosthetic valve thrombosis is associated with prosthesis dysfunction and reduced prosthesis durability.8

During recent years, sutureless surgical aortic bioprostheses have gained popularity as an alternative to conventional sutured stented bioprostheses for patients undergoing aortic valve replacement (AVR). Sutureless surgical aortic bioprostheses were introduced to facilitate implantation and shorten the procedure to reduce adverse effects associated with aortic cross‐clamping and cardiopulmonary bypass. The Perceval (LivaNova PLC, London, UK) valve is a sutureless aortic bioprosthesis made of bovine pericardium that received CE (Conformité Européenne) mark approval in 2011 and US FDA approval in 2016. It is currently the most frequently used sutureless prosthetic valve and has been implanted in more than 15 000 patients in more than 310 hospitals worldwide.9 The Perceval bioprosthesis shares structural similarities with current TAVI prosthetic valves, with a nickel‐titanium alloy stent supporting the valve and anchoring it to the aortic annulus. The prevalence of HALT and RLM in the Perceval bioprosthesis is unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of HALT and RLM by cardiac CT in patients who underwent surgical AVR and received a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. We also sought to examine the association between HALT and RLM.

Methods

Study Design

This was a single‐center prospective observational study approved by the regional Human Research Ethics Committee, Stockholm, Sweden. Informed consent was obtained from patients meeting the inclusion criteria. Study design and data collection were conducted by the study institution with no sponsor contribution.

Study Population

All patients who had undergone surgical AVR with implantation of the Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden (October 2012 to February 2016) were eligible. The criterion to implant the Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis was aortic stenosis with indication for primary isolated nonemergent AVR. Implantation was considered feasible if the aortic annulus size was between 19 and 27 mm and the ratio between the diameter of the sinotubular junction and the diameter of the aortic annulus did not exceed 1.3. A type 0 bicuspid aortic valve was a contraindication for Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis implantation. Exclusion criteria were death, severely impaired renal function (glomerular filtration rate <30 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2), unwillingness to undergo CT examination, or inability to participate in the examination for logistical reasons.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical data were obtained by chart review. We investigated the associations between HALT and RLM and baseline, procedural, and follow‐up data. At the time of the cardiac CT examination, we collected data on antithrombotic treatment to assess its effect on the prevalence of HALT and RLM. Warfarin treatment was classified as being within therapeutic range if the international normalized ratio had been >2 within 7 days of CT. We also collected data on symptoms of heart failure according to the New York Heart Association functional classification and change in New York Heart Association class at cardiac CT examination.

Sutureless Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement

Information about the Perceval bioprosthesis design (Figure S1) is presented in the Methods section of Data S1. Patients underwent sutureless bioprosthesis AVR via either full sternotomy or partial upper hemisternotomy. The surgeon determined eligibility for implantation of a sutureless bioprosthesis and the preferred incision. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established with central arterial and central or peripheral percutaneous venous cannulation. Implantation was performed as previously described10 and details are presented in the Methods section of Data S1.

Peri‐ and Postprocedural Antithrombotic Regimen

Before initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass, 400 IU heparin/kg body weight was administered. If necessary, additional heparin was administered to maintain an activated clotting time of more than 480 s during cardiopulmonary bypass. After weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass, protamine was administered at a ratio of 1.0 to 1.3 mg/100 IU of the initial dose of heparin. All patients received tranexamic acid perioperatively (10–20 mg·kg−1 before surgery followed by an infusion of 5 to 10 mg·kg−1·h−1 during the operation).

According to the standard antithrombotic protocol for aortic bioprostheses at our center, postoperative antithrombotic treatment consisted of low‐molecular‐weight heparin until full mobilization and lifelong treatment with acetylsalicylic acid 75 mg once daily. Patients without a preoperative indication for oral anticoagulation did not receive oral anticoagulants postoperatively. In patients perioperatively receiving long‐term anticoagulation treatment, warfarin or novel oral anticoagulant (dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban) treatment was paused 3 days before the operation without bridging with low‐molecular‐weight heparin. In these patients, anticoagulation therapy was readministered at day 1 postoperatively. These patients were not treated with acetylsalicylic acid.

Cardiac Computed Tomography Data Acquisition

Details regarding cardiac CT data acquisition are presented in the Methods section of Data S1. All patients were scanned using a dual‐source 2×64‐row multidetector computed tomograph (Siemens Somatom Definition Flash; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) with retrospective ECG gating and individualized contrast medium administration.

Cardiac Computed Tomography Analysis

Details regarding cardiac CT analysis are presented in Data S1. Cardiac CT examinations were analyzed independently by 2 experienced readers (level 2 according to American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association levels of CT reading competence11). Joint readings involving a third experienced reader were subsequently performed to reach a consensus.

For assessment of leaflet anatomy and motion, multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) were used as still images from selected phases of the cardiac cycle, as well as dynamic images of the entire cardiac cycle. An examination was considered nondiagnostic if artifacts prevented reliable assessment of 1 or more valve leaflet (for example, because of motion or image noise).

HALT was defined according to the definition previously proposed1: evidence of 1 or more leaflet with hypo‐attenuated thickening, with or without rigidity, identifiable in at least 2 different MPR projections. To evaluate leaflet motion, time‐resolved 1‐mm MPR were used, providing high‐quality dynamic images of the prosthetic valve throughout the cardiac cycle, in the plane of the leaflets and in a perpendicular plane adjusted to the leaflet being assessed. Leaflet motion was considered normal or reduced based on visual assessment. Leaflet motion was considered reduced when the entire cusp displayed reduced motion. The opening area of the prosthetic valve was measured using planimetry in MPR.12

During subsequent separate reading sessions, the 2 readers performed additional analyses of leaflet motion, with access only to 3‐dimensional (3D) volume‐rendered (VR) images of the aortic‐valve bioprosthesis, blinded to findings of previous MPR analyses.

Statistical Methods

Variables were described using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means and SD or medians and interquartile range (quartile Q1, Q3) for continuous variables. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or analysis of variance, and categorical or binary variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. A 2‐sided P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

Between October 2012 and February 2016, a total of 58 patients received a Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis at our center. All procedures were primary isolated AVR because of aortic stenosis. One patient had a subarachnoid hemorrhage and died 127 days postoperatively, before initiation of the study. Fifty‐seven patients were eligible for participation in the study. Ten patients were not included in the study (1 with impaired renal function, 7 unwilling to participate in the study, 2 who were indisposed for logistical reasons). Cardiac CT was performed between February and March 2016 in 47 patients (83.5% of the patients who were eligible for participation). All cardiac CT examinations were diagnostic regarding the evaluation of HALT. One examination was nondiagnostic regarding the assessment of valve leaflet motion because of motion artifacts as the result of irregular heart rhythm. Patient characteristics at the time of surgery are shown in Table 1. Cardiac CT was performed at a median of 491 days (range 36–1247 days, Q1 287, Q3 933 days) postoperatively. Patient age, sex, and surgical risk score assessed with EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Score) II did not differ significantly between excluded patients and patients who underwent cardiac CT examination (age: 73.3 years versus 74.5 years, P=0.51; female sex: 82% versus 77%, P=0.71; EuroSCORE II: 2.70 versus 1.68, P=0.20).

Table 1.

Patient and Procedural Characteristics

| Total Population (n=47) | No HALT (n=29) | HALT (n=18) | P Value | Normal Leaflet Motion (n=33) | RLM (n=13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 74.5 (5.4) | 75.6 (3.9) | 72.8 (7.1) | 0.082 | 76.5 (4.3) | 69.8 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 36 (77%) | 22 (76%) | 14 (78%) | 0.88 | 26 (79%) | 9 (69%) | 0.49 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.70 (4.96) | 27.5 (3.9) | 28.1 (6.5) | 0.69 | 27.1 (3.9) | 29.4 (7.0) | 0.16 |

| Ministernotomy | 40 (85%) | 23 (79%) | 17 (94%) | 0.35 | 26 (79%) | 13 (100%) | 0.20 |

| Prosthesis size | 0.41 | 0.40 | |||||

| Small | 4 (9%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (12%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Medium | 18 (38%) | 11 (38%) | 7 (39%) | 14 (42%) | 4 (31%) | ||

| Large | 20 (43%) | 11 (38%) | 9 (50%) | 12 (36%) | 7 (54%) | ||

| Extra large | 5 (11%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (11%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (15%) | ||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.85 | 0.84 | |||||

| >50% | 44 (94%) | 27 (93%) | 17 (94%) | 31 (94%) | 12 (92%) | ||

| 30% to 50% | 3 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (8%) | ||

| <30% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate | 0.56 | 0.27 | |||||

| >60 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 | 32 (68%) | 21 (72%) | 11 (61%) | 23 (70%) | 8 (62%) | ||

| 45 to 60 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 | 10 (21%) | 6 (21%) | 4 (22%) | 8 (24%) | 2 (15%) | ||

| 30 to 45 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 | 4 (9%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (15%) | ||

| 15 to 30 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (21%) | 4 (14%) | 6 (33%) | 0.11 | 5 (15%) | 5 (38%) | 0.084 |

| Insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus | 3 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (11%) | 0.30 | 1 (3%) | 2 (15%) | 0.13 |

| Hypertension | 34 (72%) | 21 (72%) | 13 (72%) | 0.99 | 25 (76%) | 9 (69%) | 0.65 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Transient ischemic attack | 6 (13%) | 4 (14%) | 2 (11%) | 0.79 | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 0.77 |

| Chronic lung disease | 4 (9%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.099 | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.26 |

| Hemodialysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Neurologic dysfunction | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Critical preoperative state | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.43 | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.53 |

| Active cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| History of cancer | 5 (11%) | 4 (14%) | 1 (6%) | 0.37 | 5 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0.14 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0.20 | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0.11 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (13%) | 5 (17%) | 1 (6%) | 0.24 | 5 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0.14 |

| New York Heart Association class | 0.42 | 0.91 | |||||

| I | 3 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (8%) | ||

| II | 23 (49%) | 12 (41%) | 11 (61%) | 16 (48%) | 7 (54%) | ||

| III | 21 (45%) | 15 (52%) | 6 (33%) | 15 (45%) | 5 (38%) | ||

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Previous cardiac surgery | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.43 | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.53 |

| Pacemaker | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| EuroSCORE II, mean (SD) | 2.01 (1.07) | 2.08 (1.17) | 1.91 (0.92) | 0.62 | 2.09 (1.13) | 1.82 (0.97) | 0.45 |

| Days between operation and CT, median (Q1, Q3) | 491 (287, 933) | 547 (287, 989) | 420 (289, 50) | 0.65 | 583 (364, 1045) | 331 (272, 492) | 0.095 |

Baseline and procedural characteristics in relation to HALT and leaflet motion in 47 patients who underwent cardiac CT at different time points after surgical aortic valve replacement with the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Data are n (%) unless otherwise noted. CT indicates computed tomography; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Score II; HALT, hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening; Q, quartile; RLM, reduced leaflet motion.

HALT and RLM

Validation of CT evaluation methods is presented in the Results section of Data S1. HALT was found in 18 (38%) patients, of which 10 (56%) had 1 affected leaflet, 6 (33%) had 2 affected leaflets, and 2 (11%) had HALT of all 3 leaflets. Ten right aortic valve cusps, 8 left cusps, and 10 noncoronary cusps had HALT. The mean HALT leaflet thickening was 3 mm (range 1–5 mm; Figure S2). At discharge after AVR, transaortic pressure gradients were comparable between patients with and without HALT (mean transaortic pressure gradient 15.2±5.3 mm Hg versus 15.5±5.6 mm Hg, P=0.84). RLM was seen in 13 of 18 (72%) patients with HALT. Thirty‐one patients (66%) had evidence of hypo‐attenuated lesions different from leaflet thickening (a majority located below the insertion of the prosthetic valve leaflets).

RLM was found in 13 (28%) patients, of which 11 patients had 1 leaflet with reduced motion and 2 patients had 2 leaflets with reduced motion. RLM was found in 3 right aortic valve cusps, 5 left cusps, and 7 noncoronary cusps (Figures S3 and S4). None of the patients with RLM showed clinical symptoms of aortic stenosis. At discharge after AVR, transaortic pressure gradients were comparable between patients with normal and RLM (mean transaortic pressure gradient 14.5±4.1 mm Hg versus 16.2±6.9 mm Hg, P=0.32). All patients with RLM had evidence of HALT of at least 1 leaflet and there was a significant association between RLM and the presence of HALT (P<0.001). Dynamic images are presented in Videos S1 through S7.

Patient and procedural characteristics are presented in Table 1 but the study was underpowered to detect possible associations between these characteristics and the risk of HALT and RLM. Patients with RLM were younger than patients with normal leaflet motion (69.8±5.4 years versus 76.5±4.3 years, P<0.001). We investigated a possible relation between time interval from operation to CT, and HALT/RLM but found none. However, the study might have been underpowered to detect such a difference. Implanted prosthesis size and prosthetic valve opening area in relation to HALT and leaflet motion are presented in Table S1.

Antithrombotic Treatment

All patients treated with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant had been taking the medication for at least 5 months without interruption before CT examination. Both HALT and RLM were found in patients treated with acetylsalicylic acid, warfarin, or a novel oral anticoagulant (Table 2, Figure). All patients with HALT or RLM and oral anticoagulant treatment at the time of CT had ongoing anticoagulant treatment at the time of operation or started it within 1 month after the operation. There was no time effect in relation to type of antithrombotic therapy (novel oral anticoagulant or warfarin) used during the study period.

Table 2.

Antithrombotic Treatment at the Time of CT

| Total Population (n=47) | No HALT (n=29) | HALT (n=18) | P Value | Normal Leaflet Motion (n=33) | RLM (n=13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulation treatment at the time of computed tomography | |||||||

| Warfarin | 8/47 (17%) | 4/29 (14%) | 4/18 (22%) | 0.45 | 6/33 (18%) | 2/13 (15%) | 0.82 |

| Any novel oral anticoagulant | 9/47 (19%) | 8/29 (28%) | 1/18 (6%) | 0.062 | 7/33 (21%) | 1/13 (8%) | 0.28 |

| Warfarin or any novel oral anticoagulant | 17/47 (36%) | 12/29 (41%) | 5/18 (28%) | 0.35 | 13/33 (39%) | 3/13 (23%) | 0.30 |

| Rivaroxaban | 2/47 (4%) | 2/29 (7%) | 0 | 0.25 | 2/33 (6%) | 0 | 0.36 |

| Apixaban | 7/47 (15%) | 6/29 (21%) | 1/18 (6%) | 0.16 | 5/33 (15%) | 1/13 (8%) | 0.50 |

| Dabigatran | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Platelet inhibition treatment at the time of computed tomography | |||||||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 28/47 (60%) | 15/29 (52%) | 13/18 (72%) | 0.16 | 19/33 (58%) | 9/13 (69%) | 0.47 |

Anticoagulant and platelet inhibition treatment at the time of cardiac computed tomography in relation to HALT and leaflet motion in 47 patients who underwent computed tomography at different time points after surgical aortic valve replacement with the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Data are n (%) unless otherwise noted. HALT indicates hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening; RLM, reduced leaflet motion.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart and prevalence of hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening and reduced leaflet motion in relation to anticoagulation treatment (warfarin or any novel oral anticoagulant). HALT indicates hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes are shown in Table 3. Three (6%) patients had a perioperative stroke, and 1 (2%) transient ischemic attack (at 406 days postoperatively) occurred during follow‐up. Two of these 4 patients with a cerebrovascular thromboembolic event had HALT and RLM and 2 had neither HALT nor RLM at CT examination. There were no other significant differences in clinical outcomes between the groups but the study was not designed to detect such differences.

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes

| Total Population (n=47) | No HALT (n=29) | HALT (n=18) | P Value | Normal Leaflet Motion (n=33) | RLM (n=13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paravalvular leakage grade at discharge | 0.25 | 0.36 | |||||

| None | 45 (96%) | 27 (93%) | 18 (100%) | 31 (94%) | 13 (100%) | ||

| Mild | 2 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Reoperation because of paravalvular leakage | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Device embolization perioperatively | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Conversion to sternotomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Transaortic pressure gradient at discharge | |||||||

| Maximum, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 28.9 (10.7) | 27.3 (7.3) | 31.7 (14.7) | 0.20 | 28.2 (9.5) | 31.3 (13.8) | 0.40 |

| Mean, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 15.1 (5.3) | 14.5 (4.1) | 16.2 (6.9) | 0.32 | 15.2 (5.3) | 15.5 (5.6) | 0.84 |

| New‐onset atrial fibrillation | 22 (47%) | 15 (52%) | 7 (39%) | 0.39 | 16 (48%) | 6 (46%) | 0.89 |

| Atrial fibrillation before discharge | 28 (60%) | 20 (69%) | 8 (44%) | 0.096 | 21 (64%) | 6 (46%) | 0.28 |

| Atrial fibrillation after discharge | 13 (28%) | 11 (38%) | 2 (11%) | 0.046 | 11 (33%) | 1 (8%) | 0.075 |

| De novo pacemaker | 6 (13%) | 2 (7%) | 4 (22%) | 0.13 | 3 (9%) | 3 (23%) | 0.20 |

| Stroke postoperatively excluding perioperatively | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· | 0 | 0 | ··· |

| Stroke perioperatively | 3 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (11%) | 0.30 | 1 (3%) | 2 (15%) | 0.13 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.43 | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.53 |

Clinical outcomes in relation to HALT and leaflet motion in 47 patients who underwent cardiac computed tomography at different time points after surgical aortic valve replacement with the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Data are n (%) unless otherwise noted. HALT indicates hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening; RLM, reduced leaflet motion.

Discussion

In this study, cardiac CT revealed a high prevalence of HALT and RLM among patients with a surgically implanted Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. HALT was found in all patients with RLM. Both HALT and RLM were found in patients with ongoing anticoagulation treatment.

Previous Studies of HALT and RLM

Three recently published series have reported on HALT and/or RLM detected with CT in patients who received TAVI prostheses.1, 3, 4 In 1 of these reports, a small number of different types of surgically implanted bioprostheses was also studied.4 None of these studies investigated both HALT and RLM systematically. In a series of 156 consecutive patients undergoing CT after a median of 5 days after implantation of the SAPIEN 3 (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) transcatheter valve, HALT was found in 10.3% with RLM in 50% of these cases.1 HALT was clinically insignificant in all cases and reversible by anticoagulation treatment with phenprocoumon for 3 months. In a report of 140 patients who underwent CT 1 to 3 months after implantation of the SAPIEN XT (Edwards Lifesciences) transcatheter valve, HALT was reported in 5 (4%) patients, of whom 4 were asymptomatic.3 None of these patients received anticoagulation treatment at the time of the CT scan. HALT was reversible by anticoagulation treatment with warfarin for 3 months in all 5 patients.

The Assessment of Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Bioprosthetic Valve Thrombosis and Its Treatment with Anticoagulation (RESOLVE) registry and Subclinical Aortic Valve Bioprosthesis Thrombosis Assessed with Four‐Dimensional Computed Tomography (SAVORY) registry reported the prevalence of subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves on the basis of 890 patients (84% TAVI patients, 16% surgical AVR patients) who had interpretable CT imaging done after either TAVI or surgical AVR. Reduced leaflet motion was diagnosed in 3.6% of the patients with surgical valves versus 13% of patients with transcatheter valves. Six different types of surgical bioprostheses were studied and the prevalence of RLM ranged 0% to 11% between these prosthesis types. Prevalence of RLM ranged 0% to 30% in studied transcatheter valve types. HALT was found in all patients with RLM. Patients with reduced leaflet motion had a small increase in aortic valve gradients measured with transthoracic echocardiography at CT examination. The prevalence of RLM was lower among patients receiving anticoagulation therapy compared with patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy at the time of cardiac CT (4% versus 15%). Reduced leaflet motion resolved in all 36 patients who received anticoagulation for 3 months but persisted in 20 of 22 patients not receiving anticoagulation. Reduced leaflet motion was associated with increased rates of transient ischemic attacks (4.18 versus 0.60 per 100 person‐years).

In summary, these 3 previous reports indicate that HALT and RLM can be detected on cardiac CT and could be associated with increased rates of transient ischemic attacks and a small increase in valve gradients. HALT and RLM have been demonstrated in practically all studied prosthesis types, including surgically implanted bioprostheses. Anticoagulation treatment at the time of CT has been associated with a decreased incidence of RLM and both HALT and RLM resolved with anticoagulation treatment for 3 to 6 months.1, 3, 4 These findings have led to the interpretation that HALT and RLM could be either early markers of leaflet thrombosis or equivalent to subclinical leaflet thrombosis.

Prevalence of HALT and RLM

The reported prevalence of HALT and RLM has varied considerably between published series. There are several differences between these series that might explain the variability, (eg, multiple prosthesis types, both transcatheter and surgical), the timing of cardiac CT after valve implantation, and different cardiac CT techniques.

The prevalence of HALT in the Perceval sutureless aortic bioprosthesis was high (38%) compared with previous TAVI studies (4–10%).1, 3 This may in part be related to the different prosthetic designs and to the fact that CT acquisition was generally performed late in our study, at a median of 491 days after Perceval implantation. Another explanation of the high prevalence of HALT in the present study may be the high diagnostic quality of the cardiac CT scans, with no nondiagnostic examinations, compared with 28% nondiagnostic scans in 1 previous study,3 together with the thorough evaluation by 2 experienced readers, assessing time‐resolved MPR as well as VR images.

The prevalence of RLM found in this study was higher than that reported from the RESOLVE/SAVORY study. There are differences between the RESOLVE/SAVORY study and our study. First, the diagnosis of RLM differed between the two studies, since RESOLVE/SAVORY used only 3D VR to diagnose RLM, but in our study 3D VR was only used for comparative studies and the reported prevalence of RLM was based on MPR results. Evaluation of RLM based on 3D VR images alone correlated moderately with findings based on MPR, but interobserver variability was greater for 3D VR. No cases of RLM were missed when evaluating VR images alone, but there were 3 false‐positive cases as compared with MPR assessments. Based on these findings, it is unlikely that the use of different RLM diagnosis criteria used in RESOLVE/SAVORY and our study could explain the large difference in the prevalence of RLM in surgical implanted bioprostheses between the two studies. Secondly, baseline characteristic in the RESOLVE/SAVORY surgical cohort differed from characteristics of the patients included in our study. Patients in our study were more likely to be female (77% versus 36%) and were older (74.5 years versus 71.9 years). They also more frequently had a history of transient ischemic attacks (13% versus 2.2%) but less frequently of stroke (0% versus 6.6%) and atrial fibrillation (13% versus 22.6%). Anticoagulation at the time of discharge after the operation as well as at the time of CT was more common in our cohort compared with the RESOLVE/SAVORY surgical cohort. The differences in baseline characteristics might have contributed to the differences in prevalence of RLM in surgical implanted bioprostheses between the two studies. Finally, the time interval between operation and CT differed substantially between the studies. In our study, the median time from aortic valve replacement to CT was 491 days versus 163 days in RESOLVE/SAVORY surgical cohort. The association between time interval between operation and CT and the prevalence of RLM has not been thoroughly studied, and it is unclear whether this might have influenced the differences in RLM prevalence between the 2 studies.

The large difference in prevalence of RLM in surgically implanted bioprostheses in RESOLVE/SAVORY versus in surgically implanted sutureless bioprostheses in our study could either be because of different baseline characteristics or differences in time between operation and CT. However, it cannot be excluded that the prevalence of RLM is higher in the sutureless bioprosthetic valve studied compared with standard surgically implanted bioprostheses. The Perceval prosthesis has several features in common with transcatheter valves (eg, the stent design, which could hypothetically affect the tendency for RLM).

Anticoagulation Therapy

Both HALT and reduced leaflet motion were found in patients with ongoing anticoagulation treatment. In previous studies, because of CT characteristics and findings that resolved with anticoagulation treatment, thrombosis has been considered to be a likely cause of HALT and RLM.2 The number of patients in the current study may be too small to detect differences in anticoagulation therapy. However, HALT and RLM were noted in patients receiving ongoing anticoagulation therapy, indicating that anticoagulation therapy is not a guarantee against these phenomena. This finding is supported by findings of a recent larger series of bioprosthetic valves.4, 13, 14

Although both HALT and RLM have been shown to resolve with anticoagulation therapy in previous studies, this treatment may not be generally recommended because anticoagulation generally carries a risk of major bleeding complications.15 In addition, there are sparse data regarding the association between HALT and RLM and adverse clinical events, and the risk–benefit ratio of anticoagulation treatment for HALT or RLM remains uncertain. Furthermore, it is not known for how long anticoagulation therapy should be continued or what happens when anticoagulation treatment is subsequently discontinued. Guidelines for the possible treatment of HALT and RLM are currently lacking. Current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and European Society of Cardiology guidelines state that anticoagulation treatment with a vitamin K antagonist may be considered for the first 3 months after bioprosthetic surgical AVR,16, 17 but there is no strong evidence supporting this statement and many centers prescribe only low‐dose acetylsalicylic acid after the procedure. Anticoagulation treatment recommendations after Perceval sutureless valve implantation follow the standard antithrombotic protocol for bioprosthetic valves at the implanting center.18 Our analyses cannot be regarded as recommendations regarding anticoagulation treatment after Perceval sutureless valve implantation because our findings regarding HALT and RLM are descriptive and their potential clinical implications are unknown.

Underlying Mechanism

As for other valve types, the underlying mechanism of HALT and RLM in Perceval sutureless bioprostheses is unknown. Leaflet thrombosis has been speculated to be the underlying cause because restoration of cusp thickness and leaflet motion has been noted in patients receiving warfarin. All patients with RLM in this study, as well as in a previous TAVI study,4 had evidence of HALT and it seems likely that the reduced leaflet motion is secondary to the thickening of the valve leaflets. It has been speculated that the leaflet material of transcatheter and surgical bioprostheses may to some degree be procoagulant.1 The Perceval prosthesis has several features in common with transcatheter valves (eg, the stent design may cause blood trauma and thereby induce a hypercoagulable state).1, 19 After insertion into the aortic annulus, the Perceval prosthesis inflow ring is dilated with a balloon catheter. However, the balloon should only be in contact with the inflow ring and not the prosthetic leaflets during inflation. Furthermore, HALT and RLM have been observed in both balloon‐expandable and self‐expandable transcatheter valves.1, 2, 3 Another theory relates to the fact that degenerated native valve material is not removed during TAVI procedures, which may increase the risk for HALT and RLM because the remnant native valve may be a procoagulant.1 However, in the current report, the prevalence of HALT and RLM was high despite excision of the native valve followed by complete decalcification. We found that patients with RLM were younger than patients with normal leaflet motion; however, previous data regarding the association between age and RLM are conflicting.4

Clinical Implications of HALT and RLM

The potential clinical consequences of HALT and RLM in bioprostheses in general and the Perceval sutureless valve in particular are uncertain, and only 1 previous report has shown an association between RLM and cerebrovascular events.4 The incidence of stroke after Perceval sutureless valve implantation has been reported to be low and comparable to the incidence after conventional stented surgical bioprosthesis implantation.20, 21 Implantation of the Perceval sutureless valve has been associated with satisfactory hemodynamic performance without any overall increase in transvalvular gradients over time, and a low incidence of adverse events such as structural valve degeneration or clinically apparent valve thrombosis.20, 21 However, maximum follow‐up is currently limited to 5 years with very few patients followed for more than 2 years postoperatively, which prohibits definitive conclusions regarding clinical outcomes. The potential for increased risks of adverse events related to HALT and RLM warrants systematic investigation.5

Limitations and Strengths

This was a single‐center observational study with the aim to investigate the prevalence of HALT and RLM in the Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis and it was not designed to find predictors of, nor adverse events associated with, these phenomena. The study might have been underpowered to detect differences regarding patient characteristics, postoperative outcomes, and anticoagulation treatment. It is noteworthy that several patients receiving anticoagulation therapy at the time of the CT scan demonstrated HALT as well as RLM. Patients were not included in the study at the time of valve replacement and therefore the time intervals between AVR and CT examinations varied considerably. Furthermore, no echocardiographic analyses were performed as a part of this study. Because the Perceval sutureless prosthesis has similarities with both conventional surgical as well as transcatheter aortic bioprostheses, investigation of HALT and RLM of this prosthesis is of particular interest. Other strengths of this study include the high proportion of included patients and a very low rate of nondiagnostic cardiac CT examinations.

Conclusion

HALT and RLM were frequent findings in the Perceval sutureless bioprosthesis. HALT was found in all patients with RLM. Both HALT and RLM were found in patients with ongoing anticoagulation treatment. Whether these CT findings are associated with adverse events is currently unknown and needs further study.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Mats Kleberg Foundation and a donation from Mr Fredrik Lundberg. Dalén was financially supported by Hirsch Fellowship.

Disclosures

Svenarud is a consultant for LivaNova. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Prosthesis Size

Figure S1. Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis (LivaNova, Milan, Italy).

Figure S2. Cardiac computed tomography multiplanar reformatted reconstructions of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis in middiastole. The noncoronary cusp (A) was normal, with no signs of hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening. The left cusp (B) was markedly thickened with hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening. The maximum leaflet thickness was 5 mm (C). The 3‐valve leaflets are shown simultaneously; 2 of them normal and the left cusp with hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening (D).

Figure S3. Multiplanar reformatted reconstructions for evaluation of leaflet motion in a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Top panels show images in diastole and bottom panels show images of maximum leaflet opening in systole. Images to the left show the normal right cusp (white circle) in diastole (A) and fully open in systole (B). Images to the right show the noncoronary cusp (dashed circle) of the same patient in diastole (C) and with reduced leaflet opening in systole (D). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the noncoronary cusp was also present. Dynamic images are presented in Videos S1A through S1D, S2A, S2B, and S3A through S3D.

Figure S4. 3D Volume‐rendered en face images of the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Top panels show images in diastole and bottom panels show images in systole. Images to the left show a normal bioprosthesis in diastole (A) and in systole (B). To the right, a bioprosthesis with reduced motion of the right cusp (white arrow) is shown in diastole (C) and in systole (D). Dynamic 4D volume‐rendered images are presented in Videos S4 through S7).

Videos S1. A through D, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with normal motion of all 3 leaflets. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of all 3 leaflets. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the right cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the right cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images). C, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the left cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images). D, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the noncoronary cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the noncoronary cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images).

Videos S2. A and B, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with reduced leaflet motion of one cusp. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced leaflet motion of the left cusp and normal leaflet motion of the other 2 cusps. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing markedly reduced motion of the left cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the left cusp is present.

Videos S3. A through D, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with reduced leaflet motion of 2 cusps. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced leaflet motion of the left and right cusps and normal leaflet motion of the noncoronary cusp. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced motion of the left cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the left cusp is present. C, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the right cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced motion of the right cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the right cusp is present, involving only the basal parts of the leaflet. D, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the noncoronary cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the noncoronary cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images).

Videos S4 through S7. Cardiac computed tomography (CT) time‐resolved volume rendered (4D VR) en face images of 4 different Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprostheses. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player.

Video S4. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with normal motion of all 3 leaflets, throughout the cardiac cycle.

Video S5. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with normal motion of all 3 leaflets, throughout the cardiac cycle.

Video S6. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with reduced leaflet motion of the left cusp.

Video S7. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with reduced leaflet motion of the right cusp. Reduced motion is also present in a portion of the left cusp, but not in the entire cusp (which is more reliably evaluated using multiplanar reformatted images).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005251 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005251.)28862959

References

- 1. Pache G, Schoechlin S, Blanke P, Dorfs S, Jander N, Arepalli CD, Gick M, Buettner HJ, Leipsic J, Langer M, Neumann FJ, Ruile P. Early hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening in balloon‐expandable transcatheter aortic heart valves. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2263–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, Chakravarty T, Kofoed KF, de Backer O, Asch FM, Ruiz CE, Olsen NT, Trento A, Friedman J, Berman D, Cheng W, Kashif M, Jelnin V, Kliger CA, Guo H, Pichard AD, Weissman NJ, Kapadia S, Manasse E, Bhatt DL, Leon MB, Sondergaard L. Possible subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2015–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leetmaa T, Hansson NC, Leipsic J, Jensen K, Poulsen SH, Andersen HR, Jensen JM, Webb J, Blanke P, Tang M, Norgaard BL. Early aortic transcatheter heart valve thrombosis: diagnostic value of contrast‐enhanced multidetector computed tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e001596. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chakravarty T, Sondergaard L, Friedman J, De Backer O, Berman D, Kofoed KF, Jilaihawi H, Shiota T, Abramowitz Y, Jorgensen TH, Rami T, Israr S, Fontana G, de Knegt M, Fuchs A, Lyden P, Trento A, Bhatt DL, Leon MB, Makkar RR; Resolve, Investigators S . Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. Lancet. 2017; pii: S0140‐6736(17)30757‐2. DOI: 10.1016/S0140‐6736(17)30757‐2. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laschinger JC, Wu C, Ibrahim NG, Shuren JE. Reduced leaflet motion in bioprosthetic aortic valves—the FDA perspective. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1996–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anselmino M, Andria A. Embolization from biological prosthetic aortic root. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:228–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pozsonyi Z, Lengyel M. Successful thrombolysis of late, non‐obstructive mitral bioprosthetic valve thrombosis: case report and review of the literature. J Heart Valve Dis. 2011;20:526–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roudaut R, Serri K, Lafitte S. Thrombosis of prosthetic heart valves: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Heart. 2007;93:137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LivaNova PLC announces the first patient enrolled in the PERSIST‐AVR Trial. Available at: http://www.livanova.com/investor-relations/pressreleases/news_release_2153818. Accessed May 21, 2016.

- 10. Fischlein T, Meuris B, Hakim‐Meibodi K, Misfeld M, Carrel T, Zembala M, Gaggianesi S, Madonna F, Laborde F, Asch F, Haverich A; Investigators CT . The sutureless aortic valve at 1 year: a large multicenter cohort study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1617–1626.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Budoff MJ, Cohen MC, Garcia MJ, Hodgson JM, Hundley WG, Lima JA, Manning WJ, Pohost GM, Raggi PM, Rodgers GP, Rumberger JA, Taylor AJ, Creager MA, Hirshfeld JW Jr, Lorell BH, Merli G, Rodgers GP, Tracy CM, Weitz HH; American College of Cardiology F, American Heart A, American College of Physicians Task Force on Clinical C, American Society of E, American Society of Nuclear C, Society of Atherosclerosis I, Society for Cardiovascular A, Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed T . ACCF/AHA clinical competence statement on cardiac imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2005;112:598–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pflederer T, Achenbach S. Aortic valve stenosis: CT contributions to diagnosis and therapy. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2010;4:355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansson NC, Grove EL, Andersen HR, Leipsic J, Mathiassen ON, Jensen JM, Jensen KT, Blanke P, Leetmaa T, Tang M, Krusell LR, Klaaborg KE, Christiansen EH, Terp K, Terkelsen CJ, Poulsen SH, Webb J, Botker HE, Norgaard BL. Transcatheter aortic valve thrombosis: incidence, predisposing factors, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2059–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yanagisawa R, Hayashida K, Yamada Y, Tanaka M, Yashima F, Inohara T, Arai T, Kawakami T, Maekawa Y, Tsuruta H, Itabashi Y, Murata M, Sano M, Okamoto K, Yoshitake A, Shimizu H, Jinzaki M, Fukuda K. Incidence, predictors, and mid‐term outcomes of possible leaflet thrombosis after TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; pii: S1936‐878X(16)30897‐X. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.11.005. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reynolds MW, Fahrbach K, Hauch O, Wygant G, Estok R, Cella C, Nalysnyk L. Warfarin anticoagulation and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2004;126:1938–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM III, Thomas JD; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:e57–e185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of C, European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic S , Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Baron‐Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A, Falk V, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Pierard L, Price S, Schafers HJ, Schuler G, Stepinska J, Swedberg K, Takkenberg J, Von Oppell UO, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zembala M. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2451–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perceval sutureless aortic heart valve instructions for use. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/P150011d.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2016.

- 19. Huck V, Schneider MF, Gorzelanny C, Schneider SW. The various states of von Willebrand factor and their function in physiology and pathophysiology. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meuris B, Flameng WJ, Laborde F, Folliguet TA, Haverich A, Shrestha M. Five‐year results of the pilot trial of a sutureless valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shrestha M, Fischlein T, Meuris B, Flameng W, Carrel T, Madonna F, Misfeld M , Folliguet T, Haverich A, Laborde F. European multicentre experience with the sutureless Perceval valve: clinical and haemodynamic outcomes up to 5 years in over 700 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Prosthesis Size

Figure S1. Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis (LivaNova, Milan, Italy).

Figure S2. Cardiac computed tomography multiplanar reformatted reconstructions of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis in middiastole. The noncoronary cusp (A) was normal, with no signs of hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening. The left cusp (B) was markedly thickened with hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening. The maximum leaflet thickness was 5 mm (C). The 3‐valve leaflets are shown simultaneously; 2 of them normal and the left cusp with hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening (D).

Figure S3. Multiplanar reformatted reconstructions for evaluation of leaflet motion in a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Top panels show images in diastole and bottom panels show images of maximum leaflet opening in systole. Images to the left show the normal right cusp (white circle) in diastole (A) and fully open in systole (B). Images to the right show the noncoronary cusp (dashed circle) of the same patient in diastole (C) and with reduced leaflet opening in systole (D). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the noncoronary cusp was also present. Dynamic images are presented in Videos S1A through S1D, S2A, S2B, and S3A through S3D.

Figure S4. 3D Volume‐rendered en face images of the Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis. Top panels show images in diastole and bottom panels show images in systole. Images to the left show a normal bioprosthesis in diastole (A) and in systole (B). To the right, a bioprosthesis with reduced motion of the right cusp (white arrow) is shown in diastole (C) and in systole (D). Dynamic 4D volume‐rendered images are presented in Videos S4 through S7).

Videos S1. A through D, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with normal motion of all 3 leaflets. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of all 3 leaflets. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the right cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the right cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images). C, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the left cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images). D, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the noncoronary cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the noncoronary cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images).

Videos S2. A and B, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with reduced leaflet motion of one cusp. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced leaflet motion of the left cusp and normal leaflet motion of the other 2 cusps. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing markedly reduced motion of the left cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the left cusp is present.

Videos S3. A through D, Cardiac computed tomography (CT) dynamic multiplanar reformatted reconstructions (MPR) of a Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis, with reduced leaflet motion of 2 cusps. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player. A, Images reconstructed in the opening plane of the valve, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced leaflet motion of the left and right cusps and normal leaflet motion of the noncoronary cusp. B, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the left cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced motion of the left cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the left cusp is present. C, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the right cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing reduced motion of the right cusp (located to the right in the dynamic images). Hypo‐attenuated leaflet thickening of the right cusp is present, involving only the basal parts of the leaflet. D, Images reconstructed perpendicularly to the noncoronary cusp, throughout the cardiac cycle, showing normal motion of the noncoronary cusp (located to the left in the dynamic images).

Videos S4 through S7. Cardiac computed tomography (CT) time‐resolved volume rendered (4D VR) en face images of 4 different Perceval sutureless aortic valve bioprostheses. Preferred program for viewing: VLC Media Player.

Video S4. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with normal motion of all 3 leaflets, throughout the cardiac cycle.

Video S5. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with normal motion of all 3 leaflets, throughout the cardiac cycle.

Video S6. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with reduced leaflet motion of the left cusp.

Video S7. Aortic valve bioprosthesis with reduced leaflet motion of the right cusp. Reduced motion is also present in a portion of the left cusp, but not in the entire cusp (which is more reliably evaluated using multiplanar reformatted images).