Abstract

Background

Environmental cold‐induced hypertension is common, but how to treat cold‐induced hypertension remains an obstacle. Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) is a mild cold‐sensing nonselective cation channel that is activated by menthol. Little is known about the effect of TRPM8 activation by menthol on mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and the vascular function in cold‐induced hypertension.

Methods and Results

Primary vascular smooth muscle cells from wild‐type or Trpm8−/− mice were cultured. In vitro, we confirmed that sarcoplasmic reticulum–resident TRPM8 participated in the regulation of cellular and mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in the vascular smooth muscle cells. TRPM8 activation by menthol antagonized angiotensin II induced mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and excess reactive oxygen species generation by preserving pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, which hindered reactive oxygen species–triggered Ca2+ influx and the activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. In vivo, long‐term noxious cold stimulation dramatically increased vasoconstriction and blood pressure. The activation of TRPM8 by dietary menthol inhibited vascular reactive oxygen species generation, vasoconstriction, and lowered blood pressure through attenuating excessive mitochondrial reactive oxygen species mediated the activation of RhoA/Rho kinase in a TRPM8‐dependent manner. These effects of menthol were further validated in angiotensin II–induced hypertensive mice.

Conclusions

Long‐term dietary menthol treatment targeting and preserving mitochondrial function may represent a nonpharmaceutical measure for environmental noxious cold–induced hypertension.

Keywords: calcium, hypertension, mitochondria, mouse, reactive oxygen species, sarcoplasmic reticulum, TRPM8 protein

Subject Categories: ACE/Angiotension Receptors/Renin Angiotensin System, Oxidant Stress, Hypertension, Vascular Biology

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Activation of sarcoplasmic reticulum–resident transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 channel regulates the mitochondrial function of vascular smooth muscle cells and antagonizes vascular dysfunction in hypertension.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Chronic dietary menthol targeting and preserving mitochondrial function might be a novel strategy for the management of hypertension at a population level.

Introduction

Noxious cold temperature is a nonmodifiable risk factor for hypertension. The prevalence of hypertension and related cardiovascular diseases is higher in people who live in colder areas or during colder months.1, 2 The pathogenesis of cold‐induced hypertension (CIH) involves the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system, and the inflammatory process. Among them, the overdrive of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system plays a crucial role in the development of CIH.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Although antagonism of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system was recommended to improve CIH, how to prevent CIH through nonpharmaceutical therapy in the general population remains unknown.

Mitochondria, Ca2+, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are each integral to vascular function and are thought to be involved in the development of hypertension. Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and several complexes of electron transport have been reported to be Ca2+ dependent.8 Increased physiological levels of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is the coordinated upregulation of the entire oxidative phosphorylation activity.9 PDH is one of the key dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, the activity of which is blunted by Angiotensin II (Ang II) by increasing PDH phosphorylation in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).10 Meanwhile, mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ overload impairs mitochondrial function and leads to ROS generation.11 Excessive mitochondrial ROS is implicated in the development of vascular dysfunction.12 Ang II–induced mitochondrial ROS generation promotes Ca2+ influx and, subsequently, contraction in arterial smooth muscle.13 Under pathological conditions of cytosolic Ca2+ overload, mitochondria are capable of taking up large amounts of Ca2+.14 This vicious cycle might be an important factor contributing to the excess mitochondrial ROS production in VSMCs. Indeed, ROS‐mediated upregulation of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway promotes vasoconstriction and contributes to high blood pressure (BP).15 It is worth investigating whether ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts this vicious cycle and attenuates vascular dysfunction in hypertension.

Currently, application of ROS scavengers, which eliminate the total levels of tissue and cellular ROS, has not generally achieved favorable effects on ameliorating cardiovascular diseases.16 Using mitochondria‐targeted antioxidants to alleviate mitochondrial oxidative stress might efficiently attenuate hypertension.12 The transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) channel is a mild cold‐sensing nonselective cation channel that can be activated by its specific agonist, menthol. Our previous study demonstrates that the activation of vascular TRPM8 by menthol has a favorable antihypertensive effect through inhibition of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway.17 Recently, others have shown that TRPM8 exists in both the cytomembrane and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.18 Furthermore, TRPM8 can function as an endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channel, which regulates mitochondrial function and ROS production through coupling the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake.19 It remains to be determined whether the SR‐resident TRPM8 channel regulates the vascular mitochondrial function and antagonizes noxious cold–induced vascular dysfunction in CIH.

In this study, we hypothesized that the activation of TRPM8 by chronic dietary menthol has a beneficial effect on CIH through ameliorating the vascular mitochondrial dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strain, Diet, and Treatment

TRPM8 knockout (Trpm8−/−) mice were obtained from the laboratory of Dr Patapoutian. C57BL/6J wild‐type (WT) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. To obtain an isogenic strain, heterozygous knockout mice were generated by breeding Trpm8−/− mice with WT C57BL/6J mice as previously described.20 Briefly, we intercrossed the heterozygous mice to generate Trpm8−/− mice and WT littermates, which were identified by tail DNA polymerase chain reaction screening.20 These homozygous Trpm8−/− mice and their WT littermates were maintained and male mice were used for experiments. Control mice were maintained at a temperature of 23 to 25°C, whereas mice treated with cold stimulation (CS) were exposed to 4°C in a temperature‐controlled and ventilated chamber for 4 hours every day and then maintained at a temperature of 23 to 25°C for 24 weeks (n=12 per group).21 Meanwhile, the mice were given either a normal chow diet or a normal chow diet plus 0.5% menthol (Sigma‐Aldrich). The experimental procedures were approved by the experimental animal ethics committee and conducted according to the institutional animal care guidelines (Daping Hospital, Third Military Medical University).

Cell Culture

Primary VSMCs from WT or Trpm8−/− mice were isolated and cultured as previously described.22 Briefly, freshly isolated aortas were washed twice with PBS at 4°C and carefully freed from all connective and fat tissues. The endothelium was removed by rubbing. The aortas were cut into 2‐mm sections and incubated in a 0.2% collagenase solution at 37°C with frequent shaking to detach the VSMCs from the aorta. The VSMCs were pelleted from the solution by centrifugation at 250 g for 15 minutes at 4°C, washed with PBS, and seeded onto culture plates containing DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). All cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2. Positive staining for actin was performed to identify the purity of VSMC cultures. Experiments were performed with VSMCs at passage 3 to 5.

BP Measurement

Systolic BP levels were routinely measured by tail‐cuff plethysmography (Softron BP‐98A system). On completing the scheduled treatment, mice were surgically implanted with telemetric transmitters (Data Sciences International) as previously described.23, 24 A TA11PA‐C10 radiotelemetry transmitter (Data Sciences International) for mice was used. To insert the catheter into the carotid artery in mice, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (4%) inhalation and anesthesia was maintained with mask ventilation (isoflurane 1.8%). The animals were positioned on a temperature‐controlled heating pad to maintain normothermia (37±1°C) during the surgery. After surgery, the animals were allowed to recover for 10 days, and then 24‐hour ambulatory systolic and diastolic pressures were monitored in conscious unrestrained states with a radiotelemetry data acquisition program (Dataquest ART 3.1; Data Sciences).

Implantation of Osmotic Pump

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane as described above. Ang II (0.7 mg/kg per day) was infused into mice using a 14‐day osmotic pump (Alzet). Pumps were implanted under the skin in the back of the mice.25

Vasoreactivity Measurement Using Wire Myographs

Vasoreactivity of freshly isolated mesenteric arteries was measured in a 4‐chamber wire myograph (model 610M; Danish Myo Technology) as previously described with some modifications.17 After the animals were euthanized, the mesenteric vascular bed was removed and placed in oxygenated ice‐cold Krebs solution containing (in mmol/L) 119 NaCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 11.1 d‐glucose. The second branches of the mesenteric artery were dissected and carefully freed from connective tissues. The mesenteric arterial segments were mounted in the myograph, bathed in Krebs solution, and continuously ventilated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The arterial segments were stretched to an optimal baseline tension and then stabilized for 60 minutes. Then, KCl (60 mmol/L) was injected into the organ bath to induce contraction to confirm the functional integrity of rings. The contractile response was elicited by phenylephrine (from 10−9 to 10−5 mol/L) to induce contraction response of mesenteric arteries.

Evaluation of ROS Generation in Aorta

ROS were detected using a dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescent probe for cytosolic ROS detection or MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen) for mitochondrial ROS detection. To assess superoxide production, the thoracic aorta was freshly isolated and carefully freed from connective and fat tissues in ice‐cold gassed (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Krebs solution under a dissecting microscope with some modifications.26 Briefly, the unfixed frozen aortas were quickly cut into 10‐μm thick sections using a freezing microtome and placed on Krebs‐moistened glass slides. After a 30‐minute incubation period in warm (37°C) Krebs solution, the samples were incubated at 37°C in the dark with 10 μmol/L DHE (diluted in Krebs solution) or 5 μmol/L MitoSOX Red (diluted in Krebs solution) for 30 minutes, followed by a 15‐minute wash in Krebs solution. To quantify the fluorescence, the glass slides were placed on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon TE2000; Nikon Corporation) outfitted with a 10X PlanFluor objective lens. Images were acquired and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed using NIS‐Elements 3.0 software (Nikon Instruments).

Intracellular Free Calcium Measurement

VSMCs were pretreated with menthol (100 μmol/L) or vehicle (ethanol) for 2 hours, followed by Ang II (200 nmol/L) or vehicle (saline) treatment for 4 hours. After indicated treatment, the cells were loaded with Ca2+ indicator Fura 2‐AM (2 μmol/L; Invitrogen) and 0.025% Pluronic F‐127 in physiological saline solution containing (in mmol/L) 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 11 d‐glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4), in the dark for 40 minutes at 37°C. Then, the cells were washed 3 times using physiological saline solution with or without Ca2+. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescent plate reader (Fluoroskan Ascent Fluorometer; Thermo Scientific) at emission wavelengths of 510 nm, with excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm. The changes in intracellular calcium [Ca2+]c were calculated as the ratios of the transient increases in fluorescence intensity at 340 and 380 nm.23

Mitochondrial Calcium Measurement

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was measured as previously reported with some modifications.27 The VMSCs were pretreated with menthol (100 μmol/L) or vehicle (ethanol) for 2 hours, followed by Ang II (200 nmol/L) or vehicle (saline) treatment for 4 hours. Cells were incubated with Rhod 2‐AM (5 μmol/L; Invitrogen) and 0.025% Pluronic F‐127 in extracellular solution containing (in mmol/L) 120 NaCl, 6 KCl, 0.3 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 12 glucose, 12 sucrose, and 10 HEPES‐free acid (pH 7.4), for 40 minutes at 37°C in the dark. Cells were washed 3 times with the extracellular solution with or without Ca2+ (in mmol/L): 120 NaCl, 6 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 12 glucose, 5 EGTA, and 10 HEPES‐free acid (pH 7.4). Fluorescence intensity was acquired by a fluorescent plate reader (Fluoroskan Ascent Fluorometer; Thermo Scientific) at excitation wavelengths of 552 nm, with emission wavelengths of 581 nm. Data for Rhod 2‐AM were presented as F/F0, where F is the emission at 581 nm induced by excitation at 552 nm, and F0 is the value during the pretreatment period in each experiment.

Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiratory Function and ROS Production in Permeabilized VSMCs

Mitochondrial respiratory function was determined in a 2‐channel titration injection respirometer and coupled fluorospectrometers (Oxygraph‐2k; Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). VSMCs were pretreated with menthol (100 μmol/L) or vehicle (ethanol) for 2 hours, followed by Ang II (200 nmol/L) or vehicle (saline) treatment for 4 hours. VSMCs were harvested with trypsin digestion and centrifuged at 600 rpm for 6 minutes at room temperature. Then, the pellet was resuspended in mitochondrial respiration medium (MiR05) for high‐resolution respirometry and real‐time measurement of mitochondrial ROS production. The cell suspension was transferred separately to oxygraph chambers at a final density of ≈1.5×106 cells/mL. After 10 minutes of equilibration, closing the chambers and data were acquired using DatLab software 6.1 (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria).

To assess VSMC mitochondrial respiratory function and ROS production, we applied specially designed substrate‐uncoupler‐inhibitor titrations in an extended experimental protocol as previously reported with some modifications.28 For ROS production measurement, the H2O2 calibration need to be performed before each assay. Amplex UltraRed (10 μmol/L; Invitrogeon) and horseradish peroxidase (1 U/mL; Sigma‐Aldrich) were sequentially titrated into each chamber, and 0.1 μmol/L H2O2 (Sigma‐Aldrich) was added, which was injected stepwise up to 0.3 μmol/L. Then, the linear H2O2 calibration was performed on the Amp‐Channel in DatLab.29 Routine respiration (no additives) was measured when the respiration was equalized. Then, digitonin (100 μg/106 cells) was titrated to permeabilize the plasma membrane. The respiratory leak state of complex I (CI) was detected after titration with glutamate (5 mmol/L) and malate (2 mmol/L) in the absence of ADP. The oxidative phosphorylation function of CI was induced after adding 5 mmol/L of ADP. Succinate (100 mmol/L) was added to induce oxidative phosphorylation via convergent input through both CI and complex II (CII; oxidative phosphorylation of CI and CII). Subsequently, oligomycin (0.5 μmol/L) was used to inhibit ATP synthase and induce the leak state of both CI and CII. When the respiration was stabilized, carbonyl cyanide 4‐trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone (injected stepwise up to 1.5 μmol/L) was immediately titrated to obtain the maximal uncoupled respiratory capacity of the electron transfer system. Uncoupled respiratory function of CII was measured after adding rotenone (0.5 μmol/L). Antimycin A (2.5 μmol/L) was titrated to induce residual oxygen consumption.

PDH Activity Assay

PDH activity was measured with microplate assay kits (ScienCell). Briefly, this colormetric assay is based on PDH‐catalyzed oxidation of pyruvate, where the resulting NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) can then convert a nearly colorless probe to a colored product. The intensity of the colored product is proportional to the amount of PDH in the samples, exhibiting maximum absorbance at 440 nm.

Isolation and Fraction of Subcellular Compartments

Separation of subcellular compartments, including SR fraction, cytosol, mitochondria, and nuclear from primary cultured VSMCs were isolated and purified as previously described.30 Briefly, cells were harvested with trypsin digestion and centrifuged 3 times at 600g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant and resuspended cell pellet was discarded in 20 mL of ice‐cold IBcells‐1 solution (mannitol 225 mmol/L, sucrose 75 mmol/L, EGTA 0.1 mmol/L, Tris‐HCl Ph 7.4). Cells were homogenized at 4000 rpm using a Teflon pestle. Centrifuge the homogenate at 600g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant and centrifuge at 600g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant and centrifuge at 7000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant for further separation of cytosolic and SR fractions. The pellet contains mitochondria fraction. To perform such subfraction, centrifuge supernatant at 20 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Centrifugation of the supernatant at 100 000g for 1 hour results in the separation of SR and cytosolic fraction. Gently resuspend the pellet containing mitochondria in 20 mL of ice‐cold IBcells‐2 solution (mannitol 225 mmol/L, sucrose 75 mmol/L, and 30 mmol/L Tris‐HCl Ph 7.4). Centrifuge the suspension at 7000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Collect and resuspend the mitochondrial pellet in 20 mL of ice‐cold IBcells‐2 solution. Centrifuge at 10 000g for 10 minutes at 4°C resulting in the isolation of mitochondria.

Determination of RhoA Activation

RhoA activation assay was performed as previously described.31 Briefly, samples were lysed in hypertonic buffer and GTP‐bound RohA was immunoprecipitated from cleared lysate (500 μg) with 400 μg of glutathione‐agarose–bound glutathione S‐transferase–tagged Rhotekin RhoA binding domain for RhoA. Beads were washed 3 times and the immunoprecipitate resolved on 15% SDS‐PAGE. Active RhoA was normalized to total RhoA by Western blot analysis.

Western Immunoblotting

Cells or tissues were lysed in a buffer containing 0.5 mol/L Tris, 1% NP40, 1% Triton X‐100, 1 g/L sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.5 mol/L NaCl, 0.2 mol/L EDTA, 0.01 mol/L EGTA, and 0.2 mmol/L protease inhibitor, then placed at −20°C for 20 minutes. Samples were centrifuged at 12 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris. The supernatant was collected, and the sample protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio‐Rad Protein Assay). Fifty‐microgram portions of the sample protein were separated on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels and Western blotting performed as we previously described.23 The primary antibodies used included TRPM8 (NB200‐145, Novus Biologicals), RhoA (sc‐418), MYPT1 (sc‐514261), p‐MYPT1 (sc‐377531), tubulin (sc‐134237), IP3R (sc‐271197), β‐actin (sc‐47778), and AT1R (sc‐515884) and were purchased from Santa Cruz; MLC (#3672), p‐MLC (#3675), and PDH (#2784) were purchased from Cell Signaling; and p‐PDH (ab92696) and VDAC (ab15895) were purchased from Abcam.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean±SEM. Kolmogorov–Smirnov or Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to determine whether each variable had a normal distribution. Significant differences were evaluated by 2‐tailed Student t test or ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test as appropriate. Repeated‐measures analysis was used for the comparisons of repeated measures quantitative variables. Two‐way ANOVA was used to determine the role of menthol and CS on the ROS generation and protein expression in mice aortas. The contractions were expressed as folds over KCl‐induced contraction. Concentration‐contraction curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression curve fitting using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0) to estimate Emax as the maximal response. Concentration‐response curves were analyzed by 1‐way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using either GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0) or SPSS (version 19.0, SPSS Inc).

Results

SR‐Resident TRPM8 Couples the SR Ca2+ Release to Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake in VSMCs

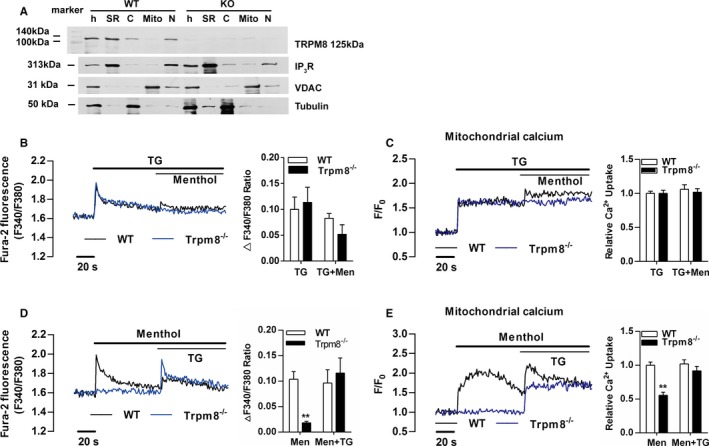

First, we examined the presence of TRPM8 in purified SR of primary cultured VSMCs from mouse aortas using the ultracentrifugation. Western blotting confirmed the colocalization of TRPM8 with the SR marker IP3R in the SR fraction of VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 1A). To assess immediate consequences of TRPM8 activation in VSMCs, we monitored menthol‐induced changes of Ca2+ concentration in cytosol ([Ca2+]c) and mitochondria ([Ca2+]m) in Ca2+‐free medium. Changes of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m in response to 300 μmol/L of menthol stimulation were simultaneously monitored using Fura‐2 and Rhod‐2, respectively. Menthol did not induce virtual [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m transients after depletion of Ca2+ stores in the SR by thapsigargin (Figure 1B and 1C). However, menthol‐induced [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m transients were detected before thapsigargin treatment in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 1D and 1E). This suggests that SR‐resident TRPM8 couples the SR Ca2+ release to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in VSMCs.

Figure 1.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) is a functional Ca2+ channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) coupling Ca2+ release to mitochondria in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). A, TRPM8 immunoreactivity was detected by the monoclonal anti‐TRPM8 antibody (125 kDa) in homogenates (h) and SR fractions of VSMCs from wild‐type (WT) but not Trpm8−/− mice. IP 3R served as an SR marker, voltage‐dependent anion channel as a mitochondrial marker, and tubulin as a cytosolic marker. Menthol (300 μmol/L)‐induced Ca2+ concentration changes in cytosol (B) and mitochondria (C) in Ca2+‐free medium was blunted by depleting calcium store using thapsigargin (TG, 1 μmol/L) in cultured VSMCs from WT and Trpm8−/− mice. After menthol (300 μmol/L) treatment, TG (1 μmol/L) induced Ca2+ concentration changes in cytosol (D) and mitochondria (E) in Ca2+‐free medium in cultured WT and Trpm8−/− VSMCs. **P<0.01 vs WT. C indicates cytosol; Mito, mitochondrial fraction; N, nuclear fraction. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. n=3. Men indicates menthol.

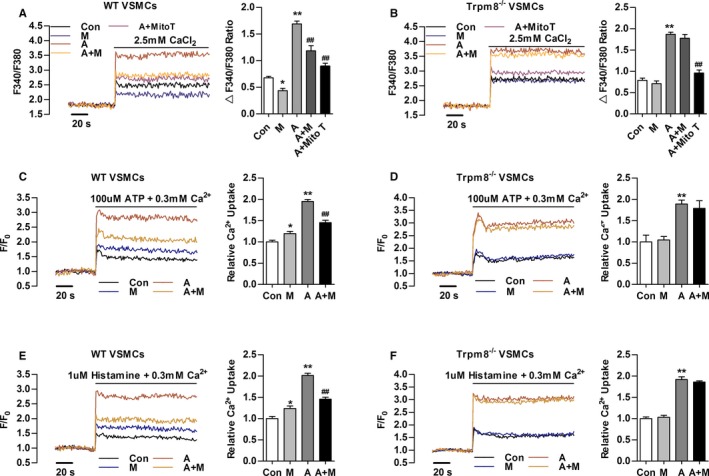

Activation of TRPM8 by Menthol Inhibits Ang II–Induced Cytosolic Ca2+ Influx and Mitochondrial Ca2+ Overload

The Ca2+ influx through plasma membrane induced by Ang II contributes to [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m elevation.13 Menthol pretreatment significantly hindered Ang II–induced Ca2+ influx in VSMCs from WT but not TRPM8−/− mice. Ang II–induced Ca2+ influx was also significantly blunted by MitoTEMPO (Sigma‐Aldrich) treatment (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by menthol inhibits Angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced cytosolic Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial Ca2+ elevation. A and B, Change in Fura‐2 fluorescence intensity showing that menthol pretreatment blunted Ang II–induced Ca2+ influx in primary cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from wild‐type (WT) but not Trpm8−/− mice in Ca2+‐free 60 mmol/L K+‐containing solution. MitoTEMPO (Mito T, 20 μmol/L) treatment hindered Ang II–induced Ca2+ influx. Mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics in WT (C) and Trpm8−/− (D) VSMCs treated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP, 100 μmol/L) in 0.3 mmol/L extracellular Ca2+. Mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics in WT (E) and Trpm8−/− (F) VSMCs treated by histamine (1 μmol/L) in 0.3 mmol/L extracellular Ca2+. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle (saline or ethanol as appropriate [Con]); ## P<0.01 vs Ang II. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. n=3. A indicates angiotensin II; A+M, menthol plus Ang II treatment; M, menthol.

After the indicated treatment, ATP‐ or histamine‐induced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was moderately increased in menthol‐treated VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 2C through 2F). Ang II treatment dramatically enhanced ATP‐ or histamine‐induced mitochondrial Ca2+ elevation. This elevation was inhibited by menthol in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 2C through 2F). Taken together, these results suggest activation of TRPM8 by menthol confers to mitochondria the ability to antagonize Ang II–induced cytosolic Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial Ca2+ overload.

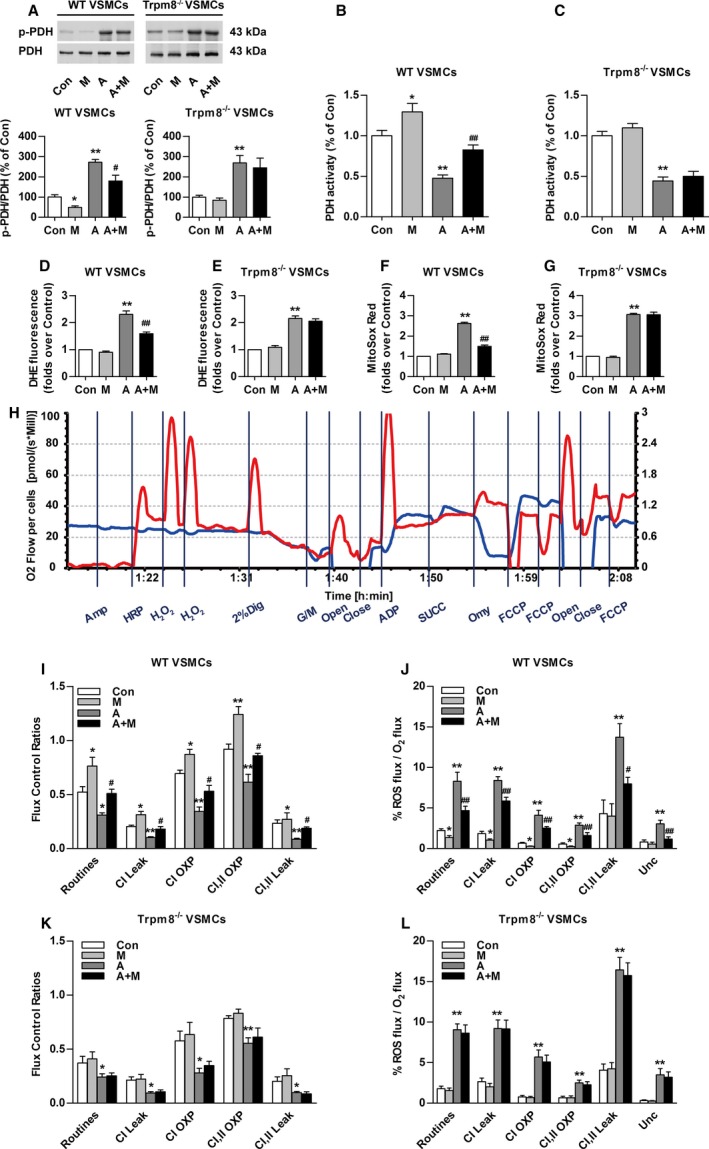

Activation of TRPM8 by Menthol Antagonizes Ang II–Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Blunts Excess ROS Generation

Mitochondrial Ca2+ transients promote mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity.19 Consistent with previous research,10 Ang II increased the ratio of phosphorylated PDH (p‐PDH) to total PDH in VSMCs from WT and Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 3A). Menthol treatment significantly blunted Ang II–induced PDH phosphorylation in a TRPM8‐dependent manner. We determined whether PDH activity follows the phosphorylation pattern. It showed that menthol administration significantly enhanced PDH activity and ameliorated Ang II–impaired PDH activity in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 3B and 3C). Menthol treatment blunted Ang II–induced total level of ROS generation in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 3D through 3G). Mitochondrial respiratory function and ROS generation in the electron transfer system were determined (Figure 3H).28, 29 The menthol‐treated VSMCs displayed a general improvement in mitochondrial respiratory function as well as decreased mitochondrial ROS production in electron transfer chain (Figure 3I and 3J). Ang II treatment significantly reduced the flux control ratios of routine respiratory, CI Leak, CI OXP, CI,II OXP, and CI,II Leak, but increased mitochondrial ROS production. Administration with menthol significantly improved Ang II–induced mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and ROS production in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 3I through 3L). Together, these results suggest that the activation of TRPM8 by menthol confers to mitochondria the ability to preserve the activity of PDH and antagonize Ang II–induced mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and excess ROS generation.

Figure 3.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation attenuates Angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. A, Western blot analysis of Ser293‐phosphorylated pyruvate dehydrogenase‐E1α (p‐PDH) and total pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) in primary cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from wild‐type (WT) or Trpm8−/− mice pretreated with menthol (100 μmol/L) or vehicle (ethanol) for 2 hours, followed by Ang II (200 nmol/L) or vehicle (saline) treatment for another 4 hours. n=3. The effect of menthol and/or Ang II on PDH activity of VSMCs from WT (B) or Trpm8−/− (C) mice was also determined. n=8. D through G, Total cytosolic (dihydroethidium [DHE]) and mitochondrial ROS (MitoSOX Red) were measured in primary cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from WT and Trpm8−/− mice. VSMCs were pretreated with menthol (M, 100 μmol/L) or vehicle (ethanol) for 2 hours, followed by Ang II (200 nmol/L) or vehicle (saline) treatment for another 4 hours. n=9 per group for DHE measurement, and n=10 per group for MitoSOX Red measurement. H, The representative image shows the measurement of mitochondrial respiratory function and ROS generation by Oxygraph‐2K. VSMCs mitochondrial respiratory function and ROS production were measured by a specially designed substrate‐uncoupler‐inhibitor titrations protocol. The red line indicates O2 consumption and the blue line shows H2O2 generation in response to the application of substrates for complex I (CI) and complex II (CII). The values are expressed in pmol/s per 106 cells. Summarized data for oxygen consumption capacity (I) and H2O2 generation (J) in the mitochondria of WT VSMCs. K and L, The same experiments as in (I and J) were performed with Trpm8−/− VSMCs. n=5 for the vehicle (saline or ethanol as appropriate) group and the menthol group. n=8 for the Ang II group, and n=6 for the menthol plus Ang II treatment group in WT VSMCs. n=6 for the vehicle group and menthol group, and n=5 for the Ang II group and menthol plus Ang II treatment group in Trpm8−/− VSMCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs Ang II. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. A indicates angiotensin II; A+M, menthol plus angiotensin II treatment; Amp, Amplex UltraRed; Close, inserting the stoppers to seal the chambers; Con, vehicle (saline or ethanol as appropriate); Dig, digitonin; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide 4‐trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone; G/M, glutamine and malate; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; M, menthol; Men, menthol; Omy, oligomycin; open, pulling out the stoppers for reoxygenation; OXP, oxidative phosphorylation; Unc, uncoupler; succinate.

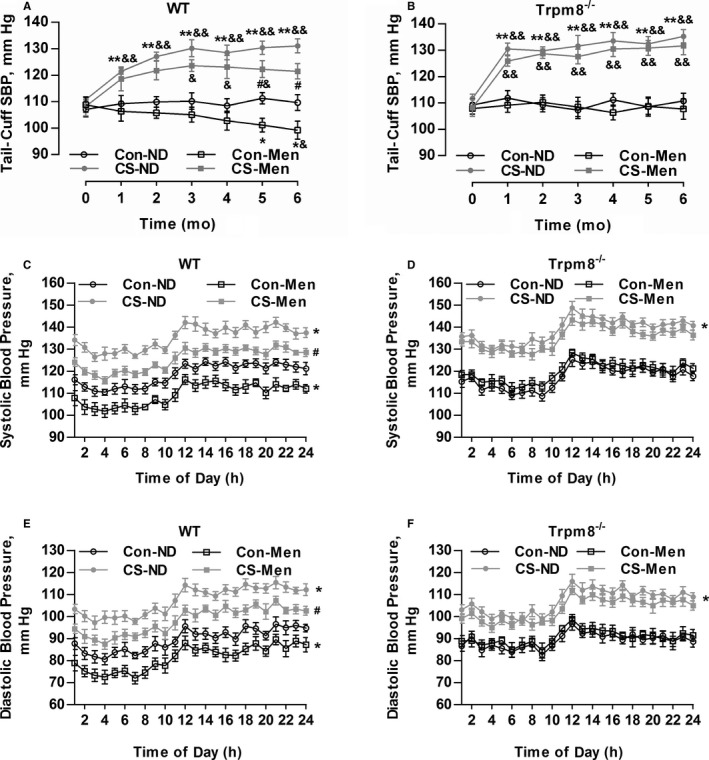

Chronic Activation of TRPM8 by Dietary Menthol Ameliorates CIH

A CIH model in mice was established as previously described.4, 21 CS significantly increased systolic BP compared with mice without CS (Figure 4A and 4B). The level of plasma Ang II was elevated in mice with CS compared with mice without CS (data not shown). Telemetric ambulatory BP shows that the cold‐induced elevation of systolic BP and diastolic BP were attenuated by dietary menthol supplementation in WT mice (Figure 4C and 4E). This effect of menthol was absent in Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 4D and 4F).

Figure 4.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by dietary menthol attenuates cold‐induced hypertension. A and B, Dietary menthol (0.5%) attenuated cold stimulation (CS)–induced elevation of systolic blood pressure (SBP) in wild‐type (WT) mice but not Trpm8−/− mice. n=6 in mice fed a normal diet (ND), n=8 in mice fed on menthol in normal temperature, and n=10 in CS‐ND and CS‐menthol group. C through F, After 6 months of treatment, the results of telemetric ambulatory blood pressure showed that dietary menthol supplementation lowered SBP and diastolic BP in WT mice in a TRPM8‐dependent manner. n=6. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs mice fed an ND; # P<0.05 vs mice with CS and ND; & P<0.05, && P<0.01 vs baseline (0 month) using repeated‐measures ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Con‐Men indicates mice fed on menthol in normal temperature; Con‐ND, mice fed an ND; CS‐Men, mice fed on menthol treated by CS.

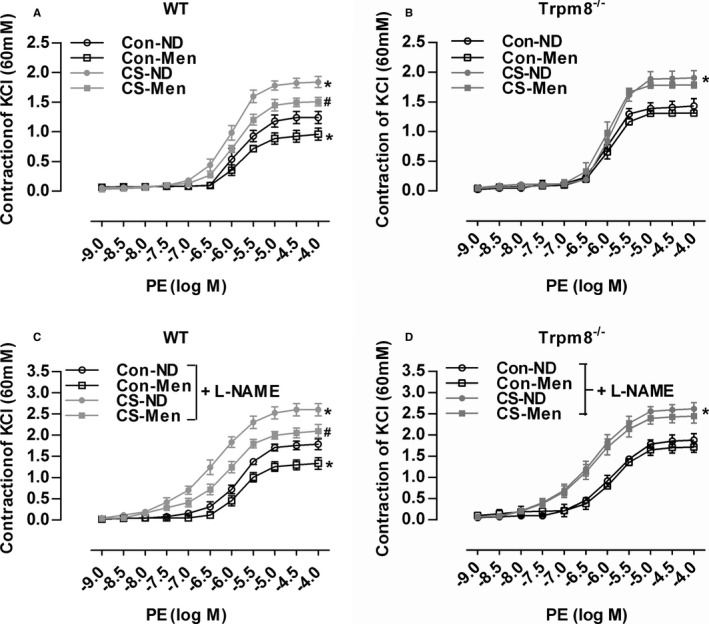

Chronic Activation of TRPM8 by Dietary Menthol Attenuates Vasoconstriction

Enhanced vasoconstriction contributes to hypertension.15 Dietary menthol significantly attenuated vasoconstriction induced by CS in WT mice but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 5A and 5B). In the presence of L‐NAME, vasoconstriction in WT mice was improved by dietary menthol in a TRPM8‐dependent manner (Figure 5C and 5D). Indicating that activation of TRPM8 by dietary menthol ameliorates CIH via inhibition of enhanced vasoconstriction.

Figure 5.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by dietary menthol attenuates vasoconstriction in cold‐induced hypertension. A and B, Dietary menthol (normal diet [ND] plus menthol supplementation [0.5%]) attenuated cold stimulation (CS)–induced vasoconstriction of mesenteric arterial rings in wild‐type (WT) but not Trpm8−/− mice. C and D, Phenylephrine (PE)‐induced vasoconstriction in mesenteric arterial rings pretreated by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG‐nitro‐l‐arginine methyl ester (L‐NAME). n=5 in WT and Trpm8−/− normal temperature (Con)‐ND group, and n=6 per group for the rest. *P<0.05 vs Con‐ND; # P<0.05 vs CS‐ND. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Men indicates menthol.

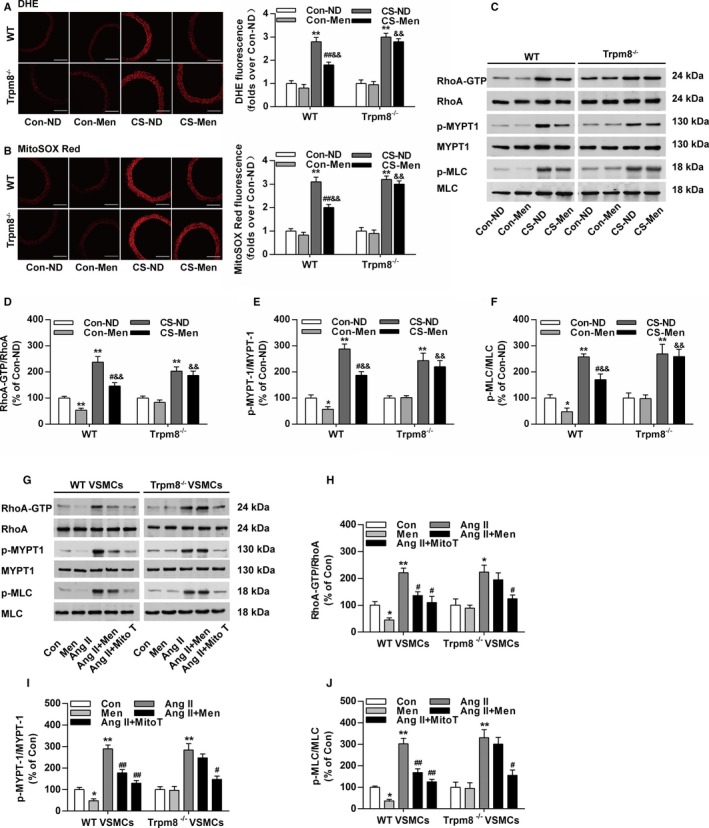

Dietary Menthol Inhibits ROS Production and RhoA/Rho Kinase Pathway Activation in CIH

The excessive ROS‐induced activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway contributes to enhanced vasoconstriction and hypertension.32, 33 ROS production in aortic rings was markedly enhanced in CS‐treated mice compared with the control WT and Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 6A and 6B). Chronic dietary menthol significantly reduced the DHE and MitoSOX Red fluorescence intensity in CS‐treated WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 6A and 6B). The ratios of RhoA‐GTP/RhoA, phosphorylated myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1/myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1, and myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase p‐MLC/MLC were significantly up‐regulated in CS‐treated WT and Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 6C through 6F). Chronic dietary menthol inhibited RhoA‐GTP, phosphorylated myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 and p‐MLC expression in WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 6C through 6F). These results suggest that the activation of TRPM8 by dietary menthol inhibited ROS generation and RhoA/Rho kinase pathway activation in the vasculature from CIH.

Figure 6.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by menthol blunts reactive oxygen species (ROS)–induced Ras homolog gene family, member A (RhoA) activation in cold‐induced hypertension. A, Cytosolic ROS measured by dihydroethidium (DHE) and (B) mitochondrial ROS measured by MitoSOX Red in the aortas from wild‐type (WT) and Trpm8−/− mice fed a normal diet (ND) or menthol treated by normal temperature (Con) or cold stimulation (CS). Bar, 200 μm. n=5. C through F, Western blot analysis of RhoA activation, myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 (MYPT1), Ser695‐phosphorylated MYPT1 (p‐MYPT1), myosin light chain (MLC), and Ser19‐phosphorylated MLC (p‐MLC) in aortas form WT and Trpm8−/− mice treated by Con‐ND, Con‐menthol, CS‐ND, or CS‐menthol. n=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs normal temperature‐ND; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs CS‐ND; && P<0.01 vs normal temperature‐menthol. G through J, Western blot analysis of RhoA activation, MYPT1, p‐MYPT1, MLC, and p‐MLC in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). The activation of TRPM8 by menthol pretreatment (100 μmol/L) inhibited the expression ratios of RhoA‐GTP/RhoA, p‐MYPT1/MYPT1, and p‐MLC/MLC in VSMCs treated by Angiotensin II (Ang II; 200 nmol/L). This effect of menthol was similar with mitoTEMPO (Mito T, 20 μmol/L). n=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs normal temperature; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs Ang II. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Men indicates ND plus menthol supplementation (0.5%); Con, vehicle (saline or ethanol as appropriate).

To further examine the effect of TRPM8 activation on mitochondrial ROS mediated RhoA/Rho kinase activation, we performed studies in primary cultured aortic VSMCs. It showed that mitochondrial‐targeting ROS scavenger MitoTEMPO efficiently inhibited Ang II–induced RhoA/Rho kinase pathway activation (Figure 6G through 6J). Menthol treatment similarly inhibited the activation of RhoA pathway in VSMCs from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 6G through 6J). These results suggest that the activation of TRPM8 by menthol prevents excessive mitochondrial ROS‐mediated RhoA/Rho kinase pathway activation in the vasculature from CIH.

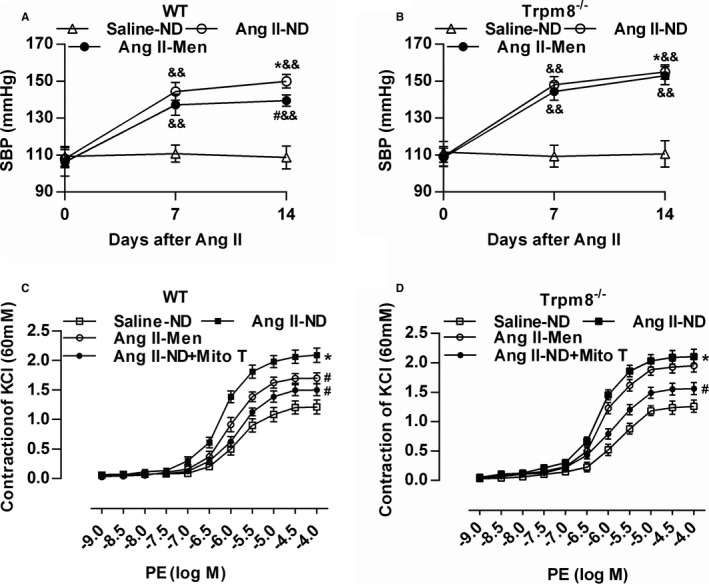

Activation of TRPM8 by Dietary Menthol Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Ang II–Induced Hypertensive Mice

Because CS caused an elevation of plasma Ang II levels (data not shown), we wanted to further validate whether the activation of TRPM8 antagonizes Ang II–induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Mice were fed a normal diet with or without menthol supplementation for 2 weeks before Ang II infusion. Ang II infusion for 14 days caused a dramatic elevation of systolic BP (Figure 7A and 7B). Menthol treatment significantly lowered systolic BP in WT mice, but this effect of menthol was absent in Trpm8−/− mice. MitoTEMPO preincubation significantly decreased vasoconstriction in mesenteric arteries from Ang II–induced hypertensive mice. Dietary menthol attenuated Ang II–induced vasoconstriction in WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 7C and 7D).

Figure 7.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by dietary menthol attenuates vascular dysfunction in Angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced hypertensive mice. A and B, Dietary menthol (0.5%) for 2 weeks before Ang II infusion (0.7 mg/kg per day) partially normalized systolic blood pressure in wild‐type (WT) but not Trpm8−/− mice. n=6 for Saline‐normal diet (ND) group, and n=8 for Ang II groups. C and D, Dietary menthol ameliorated mesenteric artery constriction in Ang II–treated WT mice but not Trpm8−/− mice. Preincubation of mitoTEMPO (Mito T, 50 μmol/L) for 2 hours blunted the enhanced vasoconstriction from Ang II–induced hypertensive mice. n=6. *P<0.05 vs saline‐ND; # P<0.05 vs Ang II‐ND; && P<0.01 vs baseline (0 day) using repeated‐measures ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Men indicates ND plus menthol supplementation (0.5%).

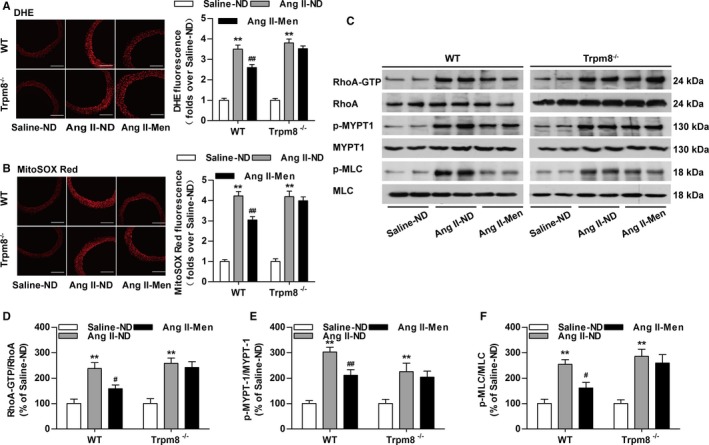

Activation of TRPM8 by Dietary Menthol Blunts ROS Generation and RhoA/Rho Kinase Pathway Activation in Ang II–Induced Hypertensive Mice

Dietary menthol blunted Ang II infusion–induced ROS production in WT but not Trpm8−/− mice (Figure 8A and 8B). Dietary menthol also inhibited the expression of RhoA‐GTP, phosphorylated myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1, and p‐MLC in vasculatures from Ang II infusion–induced hypertensive mice in vivo in a TRPM8‐dependent manner (Figure 8C through 8F). Taken together, these results suggest that the activation of TRPM8 by dietary menthol can attenuate Ang II–induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension by inhibiting ROS‐mediated RhoA/Rho kinase activation (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by dietary menthol inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and vasoconstriction in Angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced hypertensive mice. A, Cytosolic ROS measured by dihydroethidium (DHE) and (B) mitochondrial ROS measured by MitoSOX Red in the aortas from wild‐type (WT) and Trpm8−/− mice. Bar, 200 μm. n=6. C through F, Western blot analysis of RhoA activation, myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 (MYPT1), Ser695‐phosphorylated MYPT1 (p‐MYPT1), myosin light chain (MLC), and Ser19‐phosphorylated MLC (p‐MLC) in aortas. n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs saline‐normal diet (ND); # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs Ang II‐ND. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Men indicates ND plus menthol supplementation (0.5%).

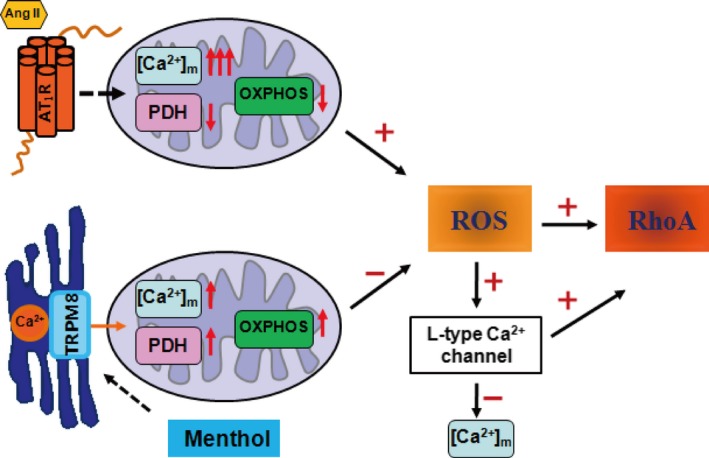

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the protective effect of transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8) activation by menthol in vascular smooth muscle cell function. On angiotensin II (Ang II) stimulation, the Ca2+ concentration in mitochondria [Ca2+]m is increased and the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) is impaired, leading to the dysfunction of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and the excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vascular smooth muscle cells. The activation of TRPM8 by menthol couples sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, which promotes the activity of PDH and OXPHOS, and inhibited ROS production. Preserving mitochondrial function by menthol blunts Ang II–induced [Ca2+]m overload and mitochondrial dysfunction through inhibiting ROS‐triggered Ca2+ influx through the L‐type Ca2+ channel.

Discussion

The major findings in this study are: (1) TRPM8 is also localized in SR and regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration and mitochondrial respiratory function in VSMCs; (2) the activation of TRPM8 by menthol attenuates Ang II–induced Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial dysfunction–induced ROS generation; (3) ROS‐mediated RhoA/Rho kinase pathway activation is blunted by menthol treatment in a TRPM8‐dependent manner in vitro and in vivo; and (4) chronic dietary menthol attenuates vascular dysfunction and hypertension in cold‐ or Ang II–treated WT but not Trpm8−/− mice. These results suggest that the antihypertensive effect of TRPM8 activation by menthol is associated with blunted Ca2+ overload–induced mitochondrial dysfunction and excessive ROS production in the vasculature, especially in CIH.

Proper function of SR and mitochondria is crucial for cellular homeostasis, and dysfunction at either site links to cardiovascular diseases.34 Ca2+ is the most prominent signaling factor that transfers from the SR to mitochondria. TRPM8 is a newly identified Ca2+ release channel in the endoplasmic reticulum.19 The activation of TRPM8 by menthol couples endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and thereby modulates mitochondrial function and ROS generation in keratinocytes.19 Three key dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid have been reported to be Ca2+ dependent.8 Mitochondrial Ca2+ transients promote mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity.19 PDH is one of the key dehydrogenases. Here, we showed that SR‐resident TRPM8 activation by menthol promotes SR Ca2+ release, which was associated with the increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in VSMCs. Menthol‐induced mitochondrial Ca2+ transients promotes PDH activity and mitochondrial respiratory function. After menthol incubation, beneficial effects were shown in WT but not Trpm8−/− VSMCs, which included moderately increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, upregulated PDH activity, enhanced mitochondrial respiratory function, decreased ROS production, and reduced Ca2+ influx. The detailed mechanism in which SR‐resident TRPM8 couples SR Ca2+ release to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake needs further investigation.

The cytosolic accumulation of Ca2+ subsequently results in mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial dysfunction.35 In the present study, Ang II treatment dramatically elevated cytosolic Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Analysis of mitochondrial function reveals that Ang II impairs PDH activity and mitochondrial respiratory function, which exacerbates ROS generation in electron transfer chain. Meanwhile, the activation of TRPM8 by menthol sufficiently blunts Ang II–induced Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial dysfunction. More importantly, mitochondrial ROS production and ROS‐mediated activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway are also attenuated by menthol treatment in a TRPM8‐dependent manner. However, various treatments might change intracellular ROS, but not a single factor directly modifies ROS and activates RhoA or L‐type calcium channels. In addition, further experiments are necessary to confirm that SR‐localized TRPM8 directly regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ levels.

RhoA can be directly activated by ROS through a redox‐sensitive motif.36 RhoA activation leads to the stimulation of Rho kinase and myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 phosphorylation, which results in increased MLC phosphorylation and smooth muscle contraction. The main regulatory mechanism of smooth muscle contraction is phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of MLC.37 The upregulation of RhoA/Rho kinase activity increased Ca2+ sensitization and enhanced vascular reactivity in hypertension.38 ROS‐dependent RhoA/Rho kinase activation in the artery has been shown to contribute to Ang II–induced hypertension in rats.39 Inhibition of RhoA/Rho kinase activation prevented long‐term Ang II infusion–induced vascular hypertrophy and fibrosis and hypertension.40, 41 In line with others' findings, our study found that TRPM8 activation blunted ROS‐induced RhoA/Rho kinase activation. However, whether TRPM8 activation affects other RhoA/Rho kinase pathways in the vasculatures cannot be ruled out. This question is worthy of further investigation.

Ang II induces hypertension through multiple mechanisms. Activation of RhoA and subsequently Rho kinase is one of the downstream signaling pathways.42 ROS‐dependent RhoA/Rho kinase activation has been shown to contribute to Ang II–induced hypertension in the artery of rats.39 Inhibition of RhoA/Rho kinase activation prevented long‐term Ang II infusion–induced vascular hypertrophy and fibrosis and hypertension.40, 41

The overdrive of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system contributes to the development of CIH. Functionally coupled Ca2+ and ROS signaling events are involved in Ang II–induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension.13 Dysfunctional mitochondria are one of the major sources of cellular ROS. A positive feedback loop in which mitochondrial‐generated ROS induces nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases activity has also been established.43 The crosstalk between nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase and mitochondria is associated with ROS‐stimulated Ca2+ flux through L‐type Ca2+ channels in Ang II–treated VSMCs.13, 44, 45 This result is compatible with our findings. Disrupting Ang II signaling by enhancing H2O2 decomposition with MitoTEMPO or inhibiting mitochondrial ROS generation with menthol treatment abolishes the stimulatory effect of ROS on L‐type Ca2+ channel activity. The blocking effect on L‐type Ca2+ channels by menthol was supported by the observations that menthol hindered CaCl2‐triggered Ca2+ influx and vasoconstriction in Ca2+‐free solution with high levels of K+.46 Our previous findings also confirm that menthol administration effectively inhibits the extracellular Ca2+ influx in the vasculature from WT but not Trpm8−/− mice.17 The inhibitory effect of menthol on L‐type Ca2+ channel current was also observed in ventricular myocytes.47 Moreover, menthol administration was also shown to increase the cytosolic Ca2+ levels in other cell types, such as neurons and brown adipocytes.20, 48, 49 This study indicated that the inhibition of ROS‐triggered Ca2+ overload by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction was responsible for the favorable effect of TRPM8 activation by menthol on vascular tone regulation. Consistent with this, MitoTEMPO and menthol treatment attenuates vasoconstriction and activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in cold‐ or Ang II–induced hypertensive mice.

TRPM8 is a cold sensor that can be activated by mild cold temperatures (10–23°C) and by cooling agents such as menthol.49 Thus, TRPM8 might be implicated in the regulation of vascular tone even at a constant temperature. During CS (4°C for 2 hours), the core body temperatures of mice were slightly decreased but were maintained above the average activation threshold (<26°C) of the TRPM8 channel (data not shown).50 This indicates that noxious cold treatment does not activate TRPM8 channels in deep tissues and organs. Our data show that noxious cold–induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension can be ameliorated by chronic dietary menthol supplementation.

Perspectives

The implications of our observations are broad. First, TRPM8 is identified as a functional channel resident in SR that couples Ca2+ transferring from SR to mitochondria in VSMCs. The activation of TRPM8 by menthol may participate in the communications between these 2 organelles. Second, we demonstrate that the activation of TRPM8 by menthol promotes mitochondrial function and confers to mitochondria the ability to antagonize the detrimental effects of Ang II. Targeting and preserving mitochondrial function by TRPM8 activation may lead to the development of therapies for CIH. Finally, menthol treatment has been demonstrated to blunt ROS‐induced Ca2+ influx in VMSCs. Intervening at the ROS amplification loop subsequently tones down Ca2+ influx and may prove to be a promising treatment for hypertension. Thus, dietary menthol might be a nonpharmaceutical measure for the prevention of hypertension in the general population, especially in patients with exposure to a cold environment.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81470536, 81370366, 81270392, and 81400351), the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB531205), and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of Ministry of Education of China. Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (cstc2012jjA10123).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lijuan Wang (Chongqing Institute of Hypertension, China) for technical assistance.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005495 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005495.)28768647

Contributor Information

Daoyan Liu, Email: daoyanliu@yahoo.com.

Zhiming Zhu, Email: zhuzm@yahoo.com.

References

- 1. Brook RD, Weder AB, Rajagopalan S. “Environmental hypertensionology” the effects of environmental factors on blood pressure in clinical practice and research. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsumoto M, Ishikawa S, Kajii E. Cumulative effects of weather on stroke incidence: a multi‐community cohort study in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun Z. Cardiovascular responses to cold exposure. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2010;2:495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crosswhite P, Sun Z. Ribonucleic acid interference knockdown of interleukin 6 attenuates cold‐induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:1484–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun Z, Cade R, Zhang Z, Alouidor J, Van H. Angiotensinogen gene knockout delays and attenuates cold‐induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shechtman O, Fregly MJ, van Bergen P, Papanek PE. Prevention of cold‐induced increase in blood pressure of rats by captopril. Hypertension. 1991;17:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peng JF, Kimura B, Fregly MJ, Phillips MI. Reduction of cold‐induced hypertension by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to angiotensinogen mRNA and AT1‐receptor mRNA in brain and blood. Hypertension. 1998;31:1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Denton RM, McCormack JG, Edgell NJ. Role of calcium ions in the regulation of intramitochondrial metabolism. Effects of Na+, Mg2+ and ruthenium red on the Ca2+‐stimulated oxidation of oxoglutarate and on pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in intact rat heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1980;190:107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love‐hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–C833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mori J, Alrob OA, Wagg CS, Harris RA, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. ANG II causes insulin resistance and induces cardiac metabolic switch and inefficiency: a critical role of PDK4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1103–H1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ, Lederer WJ. Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:10479–10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaplin NL, Nieves‐Cintron M, Fresquez AM, Navedo MF, Amberg GC. Arterial smooth muscle mitochondria amplify hydrogen peroxide microdomains functionally coupled to L‐type calcium channels. Circ Res. 2015;117:1013–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murphy E, Ardehali H, Balaban RS, DiLisa F, Dorn GW II, Kitsis RN, Otsu K, Ping P, Rizzuto R, Sack MN, Wallace D, Youle RJ; American Heart Association Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences CoCC, Council on Functional G, Translational B . Mitochondrial function, biology, and role in disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Res. 2016;118:1960–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun Q, Yue P, Ying Z, Cardounel AJ, Brook RD, Devlin R, Hwang JS, Zweier JL, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S. Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species‐mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1760–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sugamura K, Keaney JF Jr. Reactive oxygen species in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:978–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun J, Yang T, Wang P, Ma S, Zhu Z, Pu Y, Li L, Zhao Y, Xiong S, Liu D, Zhu Z. Activation of cold‐sensing transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 antagonizes vasoconstriction and hypertension through attenuating RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. Hypertension. 2014;63:1354–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen GY, Jiao HX, Wang MY, Wang RX, Lin MJ. [Decreased amplitude of [Ca(2)(+)]i elevation induced by menthol in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells of pulmonary hypertensive rats]. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2014;66:267–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bidaux G, Borowiec AS, Gordienko D, Beck B, Shapovalov GG, Lemonnier L, Flourakis M, Vandenberghe M, Slomianny C, Dewailly E, Delcourt P, Desruelles E, Ritaine A, Polakowska R, Lesage J, Chami M, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Epidermal TRPM8 channel isoform controls the balance between keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in a cold‐dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E3345–E3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ma S, Yu H, Zhao Z, Luo Z, Chen J, Ni Y, Jin R, Ma L, Wang P, Zhu Z, Li L, Zhong J, Liu D, Nilius B, Zhu Z. Activation of the cold‐sensing TRPM8 channel triggers UCP1‐dependent thermogenesis and prevents obesity. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu Z, Zhu S, Zhu J, van der Giet M, Tepel M. Endothelial dysfunction in cold‐induced hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang S, Liang B, Viollet B, Zou MH. Inhibition of the AMP‐activated protein kinase‐α2 accentuates agonist‐induced vascular smooth muscle contraction and high blood pressure in mice. Hypertension. 2011;57:1010–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li L, Wang F, Wei X, Liang Y, Cui Y, Gao F, Zhong J, Pu Y, Zhao Y, Yan Z, Arendshorst WJ, Nilius B, Chen J, Liu D, Zhu Z. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation by dietary capsaicin promotes urinary sodium excretion by inhibiting epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit‐mediated sodium reabsorption. Hypertension. 2014;64:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang D, Luo Z, Ma S, Wong WT, Ma L, Zhong J, He H, Zhao Z, Cao T, Yan Z, Liu D, Arendshorst WJ, Huang Y, Tepel M, Zhu Z. Activation of TRPV1 by dietary capsaicin improves endothelium‐dependent vasorelaxation and prevents hypertension. Cell Metab. 2010;12:130–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norlander AE, Saleh MA, Kamat NV, Ko B, Gnecco J, Zhu L, Dale BL, Iwakura Y, Hoover RS, McDonough AA, Madhur MS. Interleukin‐17A regulates renal sodium transporters and renal injury in angiotensin II‐induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma S, Ma L, Yang D, Luo Z, Hao X, Liu D, Zhu Z. Uncoupling protein 2 ablation exacerbates high‐salt intake‐induced vascular dysfunction. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feng S, Li H, Tai Y, Huang J, Su Y, Abramowitz J, Zhu MX, Birnbaumer L, Wang Y. Canonical transient receptor potential 3 channels regulate mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11011–11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xiong S, Wang P, Ma L, Gao P, Gong L, Li L, Li Q, Sun F, Zhou X, He H, Chen J, Yan Z, Liu D, Zhu Z. Ameliorating endothelial mitochondrial dysfunction restores coronary function via transient receptor potential vanilloid 1‐mediated protein kinase A/uncoupling protein 2 pathway. Hypertension. 2016;67:451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hickey AJ, Renshaw GM, Speers‐Roesch B, Richards JG, Wang Y, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ. A radical approach to beating hypoxia: depressed free radical release from heart fibres of the hypoxia‐tolerant epaulette shark (Hemiscyllum ocellatum). J Comp Physiol B. 2012;182:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wieckowski MR, Giorgi C, Lebiedzinska M, Duszynski J, Pinton P. Isolation of mitochondria‐associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1582–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meng Y, Li T, Zhou GS, Chen Y, Yu CH, Pang MX, Li W, Li Y, Zhang WY, Li X. The angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2/angiotensin (1‐7)/Mas axis protects against lung fibroblast migration and lung fibrosis by inhibiting the NOX4‐derived ROS‐mediated RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22:241–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jin L, Ying Z, Webb RC. Activation of Rho/Rho kinase signaling pathway by reactive oxygen species in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1495–H1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brown DI, Griendling KK. Regulation of signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2015;116:531–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paillard M, Tubbs E, Thiebaut PA, Gomez L, Fauconnier J, Da Silva CC, Teixeira G, Mewton N, Belaidi E, Durand A, Abrial M, Lacampagne A, Rieusset J, Ovize M. Depressing mitochondria‐reticulum interactions protects cardiomyocytes from lethal hypoxia‐reoxygenation injury. Circulation. 2013;128:1555–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCarron JG, Olson ML, Chalmers S. Mitochondrial regulation of cytosolic Ca(2)(+) signals in smooth muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heo J, Campbell SL. Mechanism of redox‐mediated guanine nucleotide exchange on redox‐active Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31003–31010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loirand G, Guerin P, Pacaud P. Rho kinases in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2006;98:322–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of calcium signaling by angiotensin II: implications in vascular physiology and pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1302–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jin L, Ying Z, Hilgers RH, Yin J, Zhao X, Imig JD, Webb RC. Increased RhoA/Rho‐kinase signaling mediates spontaneous tone in aorta from angiotensin II‐induced hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Higashi M, Shimokawa H, Hattori T, Hiroki J, Mukai Y, Morikawa K, Ichiki T, Takahashi S, Takeshita A. Long‐term inhibition of Rho‐kinase suppresses angiotensin II‐induced cardiovascular hypertrophy in rats in vivo—effect on endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase system. Circ Res. 2003;93:767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wirth A. Rho kinase and hypertension. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seko T, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Okamoto R, Moriki N, Onishi K, Isaka N, Hartshorne DJ, Nakano T. Activation of RhoA and inhibition of myosin phosphatase as important components in hypertension in vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2003;92:411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dikalov SI, Li W, Doughan AK, Blanco RR, Zafari AM. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and calcium uptake regulate activation of phagocytic NADPH oxidase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1134–R1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chaplin NL, Amberg GC. Hydrogen peroxide mediates oxidant‐dependent stimulation of arterial smooth muscle L‐type calcium channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1382–C1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chaplin NL, Amberg GC. Stimulation of arterial smooth muscle L‐type calcium channels by hydrogen peroxide requires protein kinase C. Channels (Austin). 2012;6:385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheang WS, Lam MY, Wong WT, Tian XY, Lau CW, Zhu Z, Yao X, Huang Y. Menthol relaxes rat aortae, mesenteric and coronary arteries by inhibiting calcium influx. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;702:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baylie RL, Cheng H, Langton PD, James AF. Inhibition of the cardiac L‐type calcium channel current by the TRPM8 agonist, (‐)‐menthol. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wondergem R, Ecay TW, Mahieu F, Owsianik G, Nilius B. HGF/SF and menthol increase human glioblastoma cell calcium and migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Julius D. TRP channels and pain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:355–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]