Abstract

Background

Our aim was to evaluate the association between the soluble form of neprilysin (sNEP) levels and long‐term all‐cause, cardiovascular, and acute heart failure (AHF) recurrent admissions in an ambulatory cohort of patients with heart failure. sNEP has emerged as a new biomarker with promising implications for prognosis and therapy in patients with heart failure. Reducing the recurrent admission rate of heart failure patients has become an important target of public health planning strategies.

Methods and Results

We measured sNEP levels in 1021 consecutive ambulatory heart failure patients. End points were the number of all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF hospitalizations during follow‐up. We used covariate‐adjusted incidence rate ratios to identify associations. At a median follow‐up of 3.4 years (interquartile range: 1.8–5.7), 391 (38.3%) patients died, 477 (46.7%) patients had 1901 all‐cause admissions, 324 (31.7%) patients had 770 cardiovascular admissions, and 218 (21.4%) patients had 488 AHF admissions. The medians for sNEP and amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide were 0.64 ng/mL (interquartile range: 0.39–1.22) and 1248 pg/mL (interquartile range: 538–2825), respectively. In a multivariate setting, the adjusted incidence rate ratios for the top (>1.22 ng/mL) versus the bottom (≤0.39 ng/mL) quartiles of sNEP were 1.37 (95% confidence interval: 1.03–1.82), P=0.032; 1.51 (95% confidence interval: 1.10–2.06), P=0.010; and 1.51 (95% confidence interval: 1.05–2.16), P=0.026 for all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF admissions, respectively.

Conclusions

Elevated sNEP levels predicted an increased risk of recurrent all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF admissions in ambulatory patients with heart failure.

Keywords: heart failure, neprilysin, readmission

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Biomarkers

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The circulating soluble form of the extracellular domain of neprilysin recently emerged as a promising biomarker for predicting cardiovascular death and time‐to‐first admission for heart failure in patients with chronic and acute heart failure.

In this work, we moved forward in the utility of soluble form of neprilysin for risk stratification by showing that elevated soluble form of neprilysin levels were positively and independently associated with the morbidity burden, specifically higher risk of recurrent all‐cause, cardiovascular, and heart failure admissions in patients with chronic heart failure.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Further studies should evaluate the role of this biomarker for guiding pharmacological therapy in heart failure.

Introduction

Hospitalizations in patients with heart failure (HF) remain high. Thus, reducing the rate of admissions is a critical goal of many programs and institutions.1, 2 However, the factors associated with the risk of hospitalization are not well characterized, and multiple statistical approaches have consistently shown poor ability to predict time‐to‐first admission.3, 4 To obtain a more realistic estimate of the global morbidity burden associated with HF, recent initiatives have proposed evaluating recurrent hospitalizations that occur during the natural history of the disease rather than “time‐to‐first” event.5, 6, 7 However, this transition may necessitate the collection of longitudinal data and the use of complex methodology to account for death as a terminal event (ie, conditioning for “informative censoring”).

The enzyme neprilysin breaks down various vasoactive peptides, including natriuretic peptides,8 and has a key role in the pathophysiology of HF. Over the past few years, neprilysin inhibition has emerged as a therapeutic target. The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with an ACE‐Inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM‐HF) trial revealed that sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker and neprilysin inhibitor, reduces the risk of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization for HF compared with enalapril in patients with chronic HF and reduced ejection fraction.9

The circulating soluble form of the extracellular domain of neprilysin (sNEP) has recently emerged as a promising biomarker in patients with chronic and acute heart failure (AHF) for predicting cardiovascular death and time‐to‐first admission for AHF.10, 11, 12 However, it is unknown whether this biomarker can be used to predict recurrent hospitalizations in patients with chronic HF. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between sNEP and the risk of long‐term repeated hospitalizations in a cohort of ambulatory patients with HF.

Methods

Study Population

From May 2006 to May 2013, we consecutively included in this study 1021 ambulatory patients treated at a multidisciplinary HF clinic. Data on patient demographics, medical history, vital signs, physical examination, 12‐lead ECG, laboratory test, echocardiogram, and medications were included in pre‐established electronic questionnaires and defined according to established definitions. Patients were referred to the HF clinic by the cardiology or internal medicine departments and to a lesser extent from the emergency or other hospital departments. The principal referral criterion was a HF diagnosis according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines, with at least 1 hospitalization for AHF or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Biomarkers, including sNEP, were analyzed from the same blood sample, stored at −80°, without previous freeze–thaw cycles. All samples were obtained between 09:00 am and 12:00 pm. All participants provided written informed consent, and the local ethics committee approved the study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 (revised in 1983) Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected by a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

Exposure

We measured sNEP with a modified sandwich immunoassay (human neprilysin/CD10 ELISA kit; Aviscera Bioscience, Santa Clara, CA, code No. SK00724‐01, lot No. 20111893). To improve the analytic sensitivity of the method and to obtain a lower limit of sample quantification, several modifications were made10: (1) serum aliquots were diluted one quarter in dilution buffer provided by the manufacturer (DB09) before incubation; (2) the kit was transferred to an automated robotic platform (Basic Radim Immunoassay Operator 2 [BRIO 2], Radim SpA, Pomezia, Italy) that performed all incubations at a constant temperature of 30°C, with 1000 revolutions/min mixing; and (3) initial sample incubation was extended to 150 minutes to achieve a higher slope in the calibration curve and better assay sensitivity. The studied assay measures the 52 to 750 amino acid fraction of neprilysin as immunogen (extracellular soluble fraction). This assay displays 0% cross‐reactivity with the 2 metallopeptidases most similar to this sequence, namely, endothelin converting enzymes 1 and 2. It also does not display cross‐reactivity with erythrocyte cell‐surface antigen (KELL), another protein with strong homology with neprilysin. The modified protocol displayed an analytic linearity from 0.250 to 4 ng/mL. Samples with concentrations higher than 4 ng/mL were further diluted to a final measurement range from 0.250 to 64 ng/mL. At a positive control value of 1.4 ng/mL, intra‐assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.7% and 8.9%, respectively. The intra‐assay coefficient of variation at 0.642 ng/mL (median value) was 6.5%.

Follow‐Up and Outcomes

We followed up all patients at regular predefined intervals, with additional visits when medically necessary. The schedule of visits included at minimum quarterly visits with nurses; biannual visits with physicians; and elective visits with geriatricians, psychiatrists, and rehabilitation physicians. Patients who did not attend the regular visits were contacted by telephone. We selected the total number of unplanned hospitalizations (all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF related) as the coprimary end points. Cardiovascular admissions were those that occurred because of AHF, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), arrhythmias, stroke, or other cardiovascular causes such as rupture of an aneurysm, peripheral ischemia, or aortic dissection. Acute coronary syndrome complicated with HF was adjudicated as an acute coronary syndrome. We identified hospitalizations from the clinical records of patients in the HF unit and hospital wards and from the electronic Catalan history record. We identified fatal events from the clinical records of the HF unit, hospital wards, emergency room, and general practitioners and by contacting the patients’ relatives. Furthermore, we verified data by checking them against the databases of the Catalan and Spanish health systems. For this study, the personnel in charge of clinical management and/or end point adjudication were blinded to levels of sNEP.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±1 SD or median (interquartile range [IQR]) per variable distribution. Discrete variables are presented as percentages. Baseline characteristics among the sNEP level quartiles were compared by ANOVA, Kruskall–Wallis, or χ2 tests, as appropriate (Table 1). A P value for trend was also calculated using a 2‐tail Jonckheere‐Terpstra test.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variables | sNEP‐Q1 (n=256) | sNEP‐Q2 (n=255) | sNEP‐Q3 (n=255) | sNEP‐Q4 (n=255) | P Valuea | P for Trendb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical history | ||||||

| Age, y | 69±11 | 67±12 | 66±13 | 64±14 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Male, n (%) | 188 (73.4) | 191 (74.9) | 178 (69.8) | 178 (69.8) | 0.47 | 0.20 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.44±5.83 | 28.01±5.23 | 27.93±5.15 | 27.39±5.26 | 0.44 | 0.79 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 176 (68.8) | 164 (64.3) | 151 (59.2) | 146 (57.3) | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 91 (35.5) | 83 (32.5) | 98 (38.4) | 88 (34.5) | 0.57 | 0.84 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 127 (49.6) | 117 (45.9) | 116 (45.5) | 121 (47.5) | 0.78 | 0.62 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 35 (13.7) | 46 (18.0) | 44 (17.3) | 38 (14.9) | 0.50 | 0.77 |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 110 (43.0) | 108 (42.4) | 106 (41.6) | 102 (40.0) | 0.91 | 0.48 |

| COPD, n (%) | 43 (16.8) | 50 (19.6) | 37 (14.5) | 44 (17.3) | 0.50 | 0.72 |

| MI, n (%) | 117 (45.7) | 105 (41.2) | 112 (43.9) | 103 (40.4) | 0.60 | 0.34 |

| PAD, n (%) | 45 (17.6) | 39 (15.3) | 37 (14.5) | 26 (10.2) | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Ischemic etiology, n (%) | 153 (59.8) | 124 (48.6) | 125 (49.0) | 119 (46.7) | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| HF duration, dc | 23.7 (2.5, 68) | 27.7 (3.7, 71.5) | 24.0 (3, 72) | 24.7 (4, 72) | 0.81 | 0.44 |

| AHF hospitalizations in the past 12 months | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.61 | 0.31 |

| ICD, n (%) | 37 (14.5) | 30 (11.8) | 32 (12.5) | 37 (14.5) | 0.74 | 0.92 |

| CRT, n (%) | 25 (9.8) | 17 (6.7) | 20 (7.8) | 23 (9.0) | 0.60 | 0.89 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | 0.89 | 0.54 | ||||

| Class I | 13 (5.1) | 17 (6.7) | 18 (7.1) | 13 (5.1) | ||

| Class II | 185 (72.3) | 177 (69.4) | 172 (67.5) | 178 (69.8) | ||

| Class III or IV | 58 (22.7) | 61 (23.9) | 65 (25.5) | 64 (25.1) | ||

| Heart rate, bpm | 70±13 | 72±13 | 73±16 | 73±15 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 127±25 | 126±20 | 128±22 | 126±23 | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| LVEF <50%, n (%) | 228 (89.1) | 228 (89.4) | 222 (87.1) | 216 (84.7) | 0.36 | 0.10 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.7±1.7 | 13.0±2.0 | 12.9±1.9 | 13.0±1.9 | 0.42 | 0.22 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.54±0.99 | 1.58±1.13 | 1.70±1.52 | 1.65±1.51 | 0.55 | 0.69 |

| eGFR (MDRD), mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 57±26 | 60±32 | 58±33 | 59±27 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| eGFR at admission <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 150 (58.6) | 134 (52.5) | 149 (58.4) | 141 (55.3) | 0.46 | 0.77 |

| Serum sodium, mEq/Lc | 139 (137, 142) | 140 (137, 141) | 139 (137, 141) | 139 (137, 141) | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mLc | 1318 (612, 2858) | 1068 (517, 2474) | 1388 (462, 2979) | 1249 (550, 2916) | 0.70 | 0.99 |

| NT‐proBNP ≥1000 pg/mL, n (%) | 146 (57.0) | 133 (52.2) | 153 (60.0) | 146 (57.3) | 0.35 | 0.54 |

| Neprilysin, ng/mLc | 0.25 (0.25, 0.31) | 0.53 (0.47, 0.59) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.93) | 2.41 (1.60, 5.96) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Medical treatment | ||||||

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 231 (90.2) | 242 (94.9) | 225 (88.2) | 232 (91.0) | 0.05 | 0.58 |

| Spironolactone, n (%) | 146 (57.0) | 142 (55.7) | 146 (57.3) | 163 (63.9) | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide, n (%) | 47 (18.4) | 59 (23.1) | 57 (22.4) | 66 (25.9) | 0.23 | 0.06 |

| β‐Blockers, n (%) | 235 (91.8) | 236 (92.5) | 225 (88.2) | 227 (89.0) | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| ACEI, n (%) | 214 (83.6) | 214 (83.9) | 214 (83.9) | 205 (80.4) | 0.67 | 0.36 |

| ARB, n (%) | 73 (28.5) | 64 (25.1) | 68 (26.7) | 66 (25.9) | 0.84 | 0.61 |

| ACEI or ARB, n (%) | 233 (91.0) | 232 (91.0) | 229 (89.8) | 224 (87.8) | 0.62 | 0.21 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 70 (27.3) | 111 (43.5) | 99 (38.8) | 116 (45.5) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Ivabradine, n (%) | 28 (10.9) | 17 (6.7) | 25 (9.8) | 21 (8.2) | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| Hydralazine, n (%) | 77 (30.1) | 79 (31.0) | 96 (37.6) | 102 (40.0) | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 143 (55.9) | 147 (57.6) | 146 (57.3) | 137 (53.7) | 0.81 | 0.63 |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 65 (25.4) | 68 (26.7) | 55 (21.6) | 69 (27.1) | 0.46 | 0.99 |

| Statins, n (%) | 205 (80.1) | 187 (73.3) | 195 (76.5) | 190 (74.5) | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| Platelet inhibitors, n (%) | 176 (68.8) | 167 (65.5) | 158 (62.0) | 144 (56.5) | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 109 (42.6) | 125 (49.0) | 121 (47.5) | 124 (48.6) | 0.44 | 0.23 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±1 SD, unless otherwise specified. sNEP quartiles: sNEP‐Q1, ≤0.39 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q2, 0.396 to 0.644 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q3, 0.645 to 1.22 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q4, >1.22 ng/mL. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; AHF, acute heart failure; ARB, aldosterone receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; bpm, beats per minute; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAD, peripheral artery disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; sNEP, soluble form of neprilysin.

Omnibus P value.

P value for trend.

Variable expressed as median (interquartile range).

The following aspects were crucial in the decision on how to analyze these data: (1) Since this was a HF cohort, we expect a high mortality rate; (2) There was a positive association between the number of admissions and an increased risk of subsequent death; and (3) Patient's follow‐up is usually truncated by death as terminal event, and thus, precluding new hospital readmissions. This kind of informative dropout (or censoring) can have a profound effect on the estimates, with a larger effect as the correlation between the 2 underlying processes increases. To overcome this difficulty, we used a bivariate negative binomial regression that simultaneously models the number of admissions (as counts) and mortality (as terminal event). Regression estimates for both outcomes are mutually adjusted by means of shared frailty (accounting for the positive correlation between the 2 outcomes).13 The length of stay of each admission episode was subtracted from the total observation time under the rationale that when the patient is admitted he/she is not at risk for a new admission. Crude and adjusted rates (number of events per 1 person‐year) are presented across sNEP level quartiles. We selected explanatory variables for the multivariable regression model with subject‐matter knowledge as the main criterion. Starting with this initial (oversaturated) model, a backward elimination procedure was applied with the aim to exclude variables with P≥0.25. This means that important predictors in the HF setting were left in the model unless their level of significance was >0.25. The algorithm used for backward elimination—multivariable fractional polynomial method—simultaneously determines the appropriate functional form of continuous covariates14; for our exposure sNEP, a fractional polynomial of ‐1 (inverse transformation of sNEP) was the best transformation suggested. The covariates included in the final models are listed in Table 2 and Figure 2. Risk estimates are presented as incidence rate ratios (IRR). Because of the novelty of this type of statistical methodology, there were no parameters for discrimination and calibration; thus, they are not presented. We set a 2‐sided P value of <0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were performed with Stata 14.2 (Stata Statistical Software, Release 14 [2015]; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We used the “Bivcnto” Stata module for multivariable regression analyses.

Table 2.

sNEP and Risk of Recurrent Hospitalizations

| sNEP Quartiles | IRR | 95% CI | P Value | Omnibus P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause admissionsa | ||||

| Q1 | 1.000 | ··· | ··· | 0.139 |

| Q2 | 1.072 | 0.807 to 1.425 | 0.631 | |

| Q3 | 1.227 | 0.924 to 1.628 | 0.157 | |

| Q4 | 1.369 | 1.028 to 1.824 | 0.032 | |

| Cardiovascular admissionsb | ||||

| Q1 | 1.000 | ··· | ··· | 0.045 |

| Q2 | 1.105 | 0.802 to 1.523 | 0.543 | |

| Q3 | 1.334 | 0.973 to 1.827 | 0.073 | |

| Q4 | 1.509 | 1.103 to 2.064 | 0.010 | |

| Acute heart failure admissionsc | ||||

| Q1 | 1.000 | ··· | ··· | 0.045 |

| Q2 | 0.979 | 0.673 to 1.423 | 0.910 | |

| Q3 | 1.334 | 0.930 to 1.914 | 0.117 | |

| Q4 | 1.507 | 1.051 to 2.162 | 0.026 | |

sNEP quartiles: sNEP‐Q1, ≤0.39 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q2, 0.396 to 0.644 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q3, 0.645 to 1.22 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q4, >1.22 ng/mL. CI indicates confidence interval; HF, heart failure; IRR, incidence rate ratio; NT‐proBNP, amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; sNEP, soluble form of neprilysin.

Model's covariates:

All‐cause rehospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, heart rate, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium, NT‐proBNP, left ventricular ejection fraction categories (<40%, 40–49%, ≥50%), and treatment with β‐blockers.

Cardiovascular hospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium, NT‐proBNP, and treatment with β‐blockers.

Acute heart failure hospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, sodium, NT‐proBNP, left ventricular ejection fraction categories (<40%, 40–49%, ≥50%), and treatment with β‐blockers.

Results

Baseline Characteristics Across sNEP Level Quartiles

The mean age of the sample was 66.3±12.8 years; 28.0% of the participants were women, 87.6% exhibited LVEF <40%, 51% had ischemic etiology, 24.3% were New York Heart Association class III/IV at baseline, and the median (IQR) number of admissions for AHF within the past 12 months were 1.1, 2 The median (IQR) levels of sNEP and amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide were 0.64 ng/mL (IQR: 0.39–1.22) and 1248 pg/mL (IQR: 538–2825), respectively. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics stratified by quartiles of sNEP. Age, history of hypertension, peripheral artery disease, and ischemic etiology were inversely associated with sNEP quartiles. By contrast, heart rate was positively associated with sNEP quartiles. No significant differences were found among pharmacological treatments, except for digoxin and hydralazine, which were more frequently prescribed among the upper sNEP quartiles. Conversely, antiplatelet use occurred less frequently among the lower quartiles. We found no significant differences in sex, body mass index, HF duration, New York Heart Association functional class, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, sodium, renal function markers, or amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide among quartiles of sNEP.

Outcomes

At a median follow‐up of 3.4 years (IQR: 1.8–5.7), 391 (38.3%) patients died, 1901 all‐cause admissions occurred in 477 patients (46.7%), 770 cardiovascular admissions occurred in 324 patients (31.7%), and 488 AHF admissions occurred in 218 patients (21.4%). The average numbers of all‐cause, cardiovascular, and HF admissions were 1.29±2.1, 0.7±1.4, and 0.45±1.2, respectively. The proportions of patients with 2 or more admissions were 23.5%, 9.6%, and 5.0% for all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF, respectively.

sNEP and Recurrent Hospitalizations

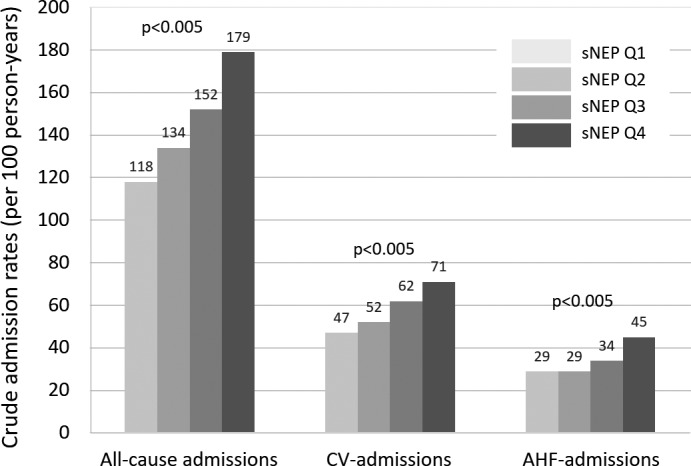

Crude admission rates across sNEP quartiles showed a significant and stepwise increase from lower to higher quartiles (P<0.005) for all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF admissions, as shown in Figure 1. The magnitude of these associations was greater for cardiovascular and AHF admissions.

Figure 1.

Crude all‐cause, cardiovascular, and acute heart failure admission rates (per 100 person‐years) across sNEP quartiles. AHF indicates acute heart failure; CV, cardiovascular; sNEP, serum neprilysin. sNEP quartiles: sNEP‐Q1, ≤0.39 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q2, 0.396 to 0.644 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q3, 0.645 to 1.22 ng/mL; sNEP‐Q4, >1.22 ng/mL.

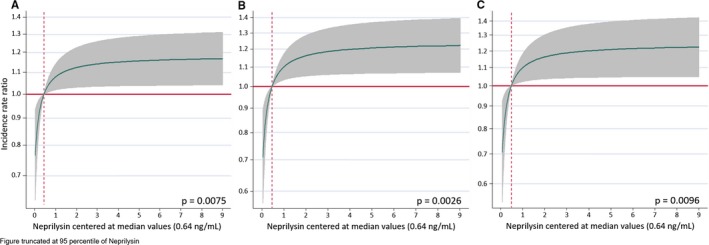

After multivariate adjustment, sNEP levels as a continuous variable were positively and significantly associated with the risk of recurrent hospitalizations. For all 3 end points, the continuum of sNEP values showed a curvilinear trajectory with an initial exponential increase in risk (up to 2 ng/mL) and a plateau effect afterward (Figure 2A through 2C). When sNEP levels were modeled as quartiles, we observed a positive and significant association for all 3 end points, as shown by a monotonic increased risk among quartiles (Table 2). The adjusted IRR for the top (>1.22 ng/mL) versus the bottom (≤0.39 ng/mL) quartiles for sNEP were 1.37 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03–1.82), P=0.032; 1.51 (95% CI: 1.10–2.06), P=0.010; and 1.51 (95% CI: 1.05–2.16), P=0.026 for all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF admissions, respectively.

Figure 2.

Functional form of sNEP. A, All‐cause readmissions. B, Cardiovascular readmissions. C, Acute heart failure readmissions. Estimates of risk were adjusted for: (A) All‐cause rehospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, heart rate, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium, NT‐proBNP, left ventricular ejection fraction categories (<40%, 40–49%, ≥50%), and treatment with β‐blockers. B, Cardiovascular hospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium, NT‐proBNP, and treatment with β‐blockers. C, Acute heart failure hospitalizations: age, HF duration, NYHA class, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, sodium, NT‐proBNP, left ventricular ejection fraction categories (<40%, 40–49%, ≥50%), and treatment with β‐blockers. Vertical dotted lines represent the median on sNEP. Horizontal red lines represent zero risk. HF indicates heart failure; NT‐proBNP, amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; sNEP, serum neprilysin.

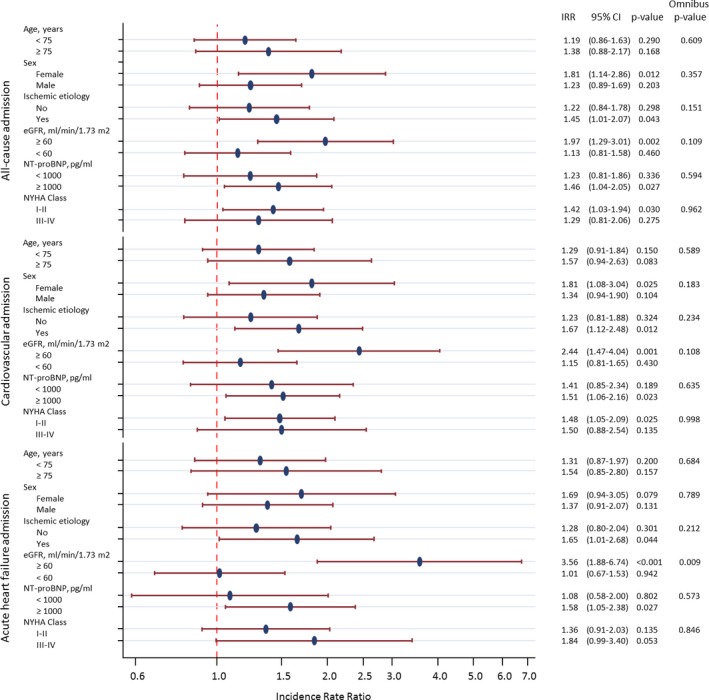

We found no interactions between sNEP levels and any of the most important subgroups (ie, age, sex, New York Heart Association class, ischemic etiology, and amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide status), except for the presence of renal dysfunction (Figure 3). Thus, when renal dysfunction was present, the magnitude of the association between sNEP levels and the end points was less evident.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis. CI indicates confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula); IRR, incidence rate ratio; NT‐proBNP, amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

A sensitivity analysis that included high‐sensitivity troponin T and ST‐2 when available (n=803) revealed that sNEP levels (top quartile: >1.27 ng/mL versus bottom quartile: <0.42 ng/mL) remained significantly associated with a higher risk of recurrent all‐cause admission (IRR: 1.50 [95% CI: 1.14–1.96], P=0.004), cardiovascular admission (IRR: 1.63 [95% CI: 1.19–2.23], P=0.002), and AHF admission (IRR: 1.94 [95% CI: 1.34–2.81], P<0.001).

Discussion

In this large cohort of ambulatory patients with chronic HF and predominantly reduced LVEF, we found that sNEP levels were strongly associated with the risk of recurrent long‐term all‐cause, cardiovascular, and AHF admissions. These results replicate our previous findings10, 11, 12 and provide further evidence regarding the utility of this biomarker in the prediction of recurrent hospitalizations, an end point of clinical significance that currently cannot be predicted accurately with standard prognostic factors.3, 4

Existing approaches aimed to investigate the predictive ability of a biomarker and the risk of hospitalization are usually based on time‐to‐first event analysis. Indeed, time‐to‐first admission in short‐term analyses has become an important target for planning decision strategies.3, 4, 15 However, this traditional approach does not include information regarding events that take place after the initial event; thus, it is not an optimal approach to evaluating chronic conditions such as HF, where recurrent hospitalizations are common.5, 7, 16 In addition, compared with analyses of repeated events, time‐to‐first‐event approaches are much less powerful for detecting treatment differences and/or biomarker predictivity.5, 7, 16 Recent initiatives have advocated a more comprehensive portrayal of the natural course of HF by analyzing all hospitalizations that occur during follow‐up.5, 6, 7, 16, 17 Furthermore, recent HF trials have reported the effect of interventions on repeated events.18, 19 For example, the ongoing multinational trial PARAGON‐HF, which was designed to evaluate the effect of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction, selected as a primary end point the cumulative number of a composite of cardiovascular deaths and HF admissions (first and recurrent) (trial no. NCT01920711 on clinicaltrials.gov).

sNEP as a Biomarker in HF

Neprilysin, also called neutral endopeptidase, is a ubiquitous zinc‐dependent enzyme with diverse substrates.8 In the cardiovascular system, neprilysin cleaves various vasoactive peptides, some of which have opposing vascular and neuroendocrine effects. For example, the neprilysin targets natriuretic peptide, adrenomedullin, and bradykinin have vasodilation effects, while angiotensins I and II and endothelin‐1 have vasoconstriction effects.8 Long after it was first discovered, neprilysin is once again relevant to cardiovascular medicine because of the impressive clinical benefits that resulted from the combination of neprilysin inhibition and angiotensin 2 type 1 receptor blockade in the PARADIGM‐HF trial.9, 18

Neprilysin, like other membrane‐bound metalloproteases, is released from the cell surface, producing a nonmembrane‐associated form that retains catalytic activity.8 Values for neprilysin activity in serum were reported 30 years ago in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.20 Evidence supporting its use as a biomarker is more recent. sNEP levels are consistently associated with risk of the composite of cardiovascular death and/or HF first readmission in chronic and AHF,10, 11, 12 independent of traditional risk factors such as natriuretic peptides. Interestingly, for this same composite end point, a head‐to‐head comparison of sNEP versus amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide levels in 797 patients with ambulatory HF revealed good calibration and similar discrimination and reclassification for both biomarkers. However, only sNEP improved overall goodness‐of‐fit.12

More recently, and in concordance with our findings, sNEP was positively associated with a higher risk of recurrent hospitalizations in a small sample of patients admitted with AHF.21 sNEP values in AHF and chronic HF were not significantly different, and the prognostic effect in both HF conditions had a similar effect size.10, 11, 12, 21 In light of previous findings and those of the present study, we postulate that sNEP levels are a reliable surrogate for neprilysin activity and, therefore, a proxy for various neurohormonal processes, including natriuretic peptide degradation.8 Moreover, sNEP has some potential advantages over standard biomarkers such as natriuretic peptides: First, sNEP levels are less affected by comorbidities such as obesity and renal dysfunction.8, 10, 11, 12 Second, sNEP levels are not substantially affected by age, sex, or functional/clinical status.8, 10, 11, 12, 21 For example, mean sNEP values in patients with acute and chronic HF are similar, suggesting that this biomarker may have more of a role in identifying phenotypes rather than clinical or hemodynamic scenarios.8, 10, 11, 12, 21 However, there are some areas of concern that must be addressed: First, there is little information about the stability of sNEP, and preanalytical management of samples is not well defined.8 Second, data comparisons among the different commercially available immunoassays have revealed a lack of reproducibility; thus, these assays require further refinement and validation.8 Third, there is little information about the role of sNEP in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction; indeed, a recent study found that sNEP levels did not predict adverse outcomes in a population of patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction.22 Fourth, since neprilysin activity affects the degradation of >50 vasopeptides, its exact pathophysiological role in chronic HF is not yet fully understood.

Future Directions

The results of the PARADIGM‐HF trial support the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan, a combination of an angiotensin receptor blocker and neprilysin inhibitor, as a therapeutic agent in patients with chronic HF. In the PARADIGM‐HF trial, sacubitril/valsartan reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization for HF compared with enalapril in patients with chronic HF and reduced LVEF.9 An analysis of recurrent hospitalizations revealed that the sacubitril/valsartan group had 15.6%, 16.0%, and 23.0% fewer all‐cause, cardiovascular, and HF hospitalizations, respectively, than the enalapril group.18 However, although these benefits likely apply to the most important subgroups of HF, we speculate that measuring neprilysin activity may be useful not only for identifying patients who will benefit the most from sacubitril/valsartan but also for tailoring the intensity of treatment.

Study Limitations

There are important limitations to the present study that need to be addressed: First, this is an observational single‐center study, and these conditions may influence the applicability of our results to other populations and impede conclusions regarding cause and effect. Second, as stated above, there are serious analytical issues with respect to sNEP measurement that must be resolved before it can be implemented in daily clinical practice. Third, our study sample comprised mainly patients with HF of ischemic etiology and reduced LVEF. As such, it is unclear whether our findings can be extrapolated to the entire spectrum of patients with HF. Fourth, the lack of serial assessment of this biomarker precluded obtaining information regarding the kinetics of sNEP during the follow‐up. Fifth, because of the novelty of the statistical methodology that we used, there are no parameters for discrimination and calibration; thus, they are not presented.

Conclusion

In patients with chronic HF, levels of sNEP were positively and independently associated with the risk of recurrent all‐cause, cardiovascular, and HF admissions in a long‐term follow‐up period. Further studies are warranted to confirm these results and explore whether sNEP levels can be used to tailor angiotensin receptor blocker and neprilysin inhibitor therapy in patients with HF.

Sources of Funding

The study was funded by grants from Biomedical Research Networking Centres (CIBER) Cardiovascular 16/11/00420, 16/11/00403, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), and Integrated Project of Excellence PIE15/00013.

Disclosures

Julio Núñez has received speaker fees from Novartis, Vifor Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and Abbott. Sanchis has received speaker fees from Astra Zeneca and Abbott. Miñana has received speaker fees from Abbott. Antoni Bayes‐Genis received board membership fees and travel expenses from Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Critical Diagnostics. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005712 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005712.)28862951

References

- 1. United States Department of Health and Human Services . Hospital quality overview. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/staticpages/for consumers/for‐consumers.aspx. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- 2. Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012;126:501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, Patlolla V, Bernheim SM, Keenan PS, Krumholz HM. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1371–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frizzell JD, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Yancy CW, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC, Laskey WK. Prediction of 30‐day all‐cause readmissions in patients hospitalized for heart failure: comparison of machine learning and other statistical approaches. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anker SD, McMurray JJ. Time to move on from ‘time‐to‐first’: should all events be included in the analysis of clinical trials? Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2764–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rogers JK, Pocock SJ, McMurray JJ, Granger CB, Michelson EL, Östergren J, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Yusuf S. Analysing recurrent hospitalizations in heart failure: a review of statistical methodology, with application to CHARM‐Preserved. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bayes‐Genis A, Núñez J, Núñez E, Martínez JB, Ferrer MP, de Antonio M, Zamora E, Sanchis J, Rosés JL. Multi‐biomarker profiling and recurrent hospitalizations in heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bayes‐Genis A, Barallat J, Richards AM. A test in context: neprilysin: function, inhibition, and biomarker. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bayes‐Genis A, Barallat J, Galan A, de Antonio M, Domingo M, Zamora E, Urrutia A, Lupón J. Soluble neprilysin is predictive of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bayés‐Genís A, Barallat J, Pascual D, Nuñez J, Miñana G, Sánchez‐Mas J, Galan A, Sanchis J, Zamora E, Pérez‐Martínez MT, Lupón J. Prognostic value and kinetics of soluble neprilysin in acute heart failure: a pilot study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayes‐Genis A, Barallat J, Galán A, de Antonio M, Domingo M, Zamora E, Gastelurrutia P, Vila J, Peñafiel J, Gálvez‐Montón C, Lupón J. Multimarker strategy for heart failure prognostication. Value of neurohormonal biomarkers: neprilysin vs NT‐proBNP. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68:1075–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu X, Hardin JW. Regression models for bivariate count outcomes. Stata J. 2016;16:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model‐Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Analysis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Di Tano G, De Maria R, Gonzini L, Aspromonte N, Di Lenarda A, Feola M, Marini M, Milli M, Misuraca G, Mortara A, Oliva F, Pulignano G, Russo G, Senni M, Tavazzi L; IN‐HF Outcome Investigators . The 30‐day metric in acute heart failure revisited: data from IN‐HF Outcome, an Italian nationwide cardiology registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:1032–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rogers JK, Jhund PS, Perez AC, Böhm M, Cleland JG, Gullestad L, Kjekshus J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Wikstrand J, Wedel H, McMurray JJ, Pocock SJ. Effect of rosuvastatin on repeat heart failure hospitalizations: the CORONA Trial (Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Núñez J, Núñez E, Sanchis J. Spironolactone in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Rev Clin Esp. 2016;216:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile M, Andersen K, Arango JL, Arnold JM, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Boytsov S, Burgess LJ, Cabrera W, Calvo C, Chen CH, Dukat A, Duarte YC, Erglis A, Fu M, Gomez E, Gonzàlez‐Medina A, Hagège AA, Huang J, Katova T, Kiatchoosakun S, Kim KS, Kozan Ö, Llamas EB, Martinez F, Merkely B, Mendoza I, Mosterd A, Negrusz‐Kawecka M, Peuhkurinen K, Ramires FJ, Refsgaard J, Rosenthal A, Senni M, Sibulo AS Jr, Silva‐Cardoso J, Squire IB, Starling RC, Teerlink JR, Vanhaecke J, Vinereanu D, Wong RC; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Coordinators . Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2015;131:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Núñez J, Llàcer P, Bertomeu‐González V, Bosch MJ, Merlos P, García‐Blas S, Montagud V, Bodí V, Bertomeu‐Martínez V, Pedrosa V, Mendizábal A, Cordero A, Gallego J, Palau P, Miñana G, Santas E, Morell S, Llàcer A, Chorro FJ, Sanchis J, Fácila L; CHANCE‐HF Investigators . Carbohydrate antigen‐125‐guided therapy in acute heart failure: CHANCE‐HF: a randomized study. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson AR, Coalson JJ, Ashton J, Larumbide M, Erdös EG. Neutral endopeptidase in serum samples from patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Comparison with angiotensin‐converting enzyme. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Núñez J, Núñez E, Miñana G, Carratalá A, Sanchis J, Lupón J, Barallat J, Pastor MC, Pascual‐Figal D, Bayés‐Genís A. Serum neprilysin and recurrent hospitalizations after acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:742–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goliasch G, Pavo N, Zotter‐Tufaro C, Kammerlander A, Duca F, Mascherbauer J, Bonderman D. Soluble neprilysin does not correlate with outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]