Abstract

Background

The impact of different types of extracranial bleeding events on health‐related quality of life and health‐state utility among patients with atrial fibrillation is not well understood.

Methods and Results

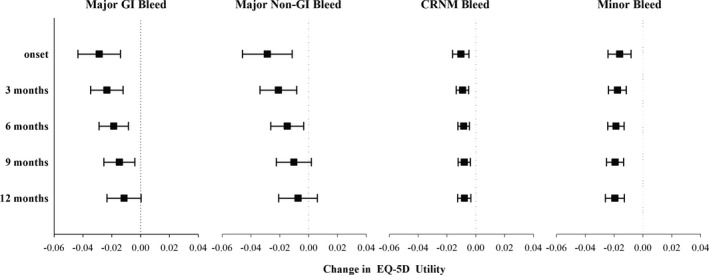

The ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) Trial compared edoxaban with warfarin with respect to the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation. Data from the EuroQol‐5D (EQ‐5D‐3L) questionnaire, prospectively collected at 3‐month intervals for up to 48 months, were used to estimate the impact of different categories of bleeding events on health‐state utility over 12 months following the event. Longitudinal mixed‐effect models revealed that major gastrointestinal bleeds and major nongastrointestinal bleeds were associated with significant immediate decreases in utility scores (−0.029 [−0.044 to −0.014; P<0.001] and −0.029 [−0.046 to −0.012; P=0.001], respectively). These effects decreased in magnitude over time, and were no longer significant for major nongastrointestinal bleeds at 9 months, but remained borderline significant for major gastrointestinal bleeds at 12 months. Clinically relevant nonmajor and minor bleeds were associated with smaller but measurable immediate impacts on utility (−0.010 [−0.016 to −0.005] and −0.016 [−0.024 to −0.008]; P<0.001 for both), which remained relatively constant and statistically significant over the 12 months following the bleeding event.

Conclusions

All categories of bleeding events were associated with negative impacts on health‐state utility in patients with atrial fibrillation. Major bleeds were associated with relatively large immediate decreases in utility scores that gradually diminished over 12 months; clinically relevant nonmajor and minor bleeds were associated with smaller immediate decreases in utility that persisted over 12 months.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/. Unique identifier: NCT00781391.

Keywords: anticoagulation, bleeding, quality of life, utility

Subject Categories: Complications, Quality and Outcomes, Arrhythmias

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The impact of different types of extracranial bleeding events on health‐state utility among patients with atrial fibrillation was examined using data from the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) trial.

Compared with clinically relevant nonmajor and minor bleeds, major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeds were associated with larger immediate decrements in utility scores that decreased gradually over the year following the bleeding event and were no longer statistically significant at 12 months.

In contrast, clinically relevant and minor bleeding events were associated with smaller but statistically significant initial decreases in utility that persisted for 12 months.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

These findings have potential use in future studies of the net clinical benefit and cost‐effectiveness of alternative strategies for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Introduction

Contemporary management of atrial fibrillation (AF) imposes many challenges. Anticoagulation in patients with AF involves a careful balance between maximizing the benefit with respect to the prevention of stroke while minimizing the bleeding risk. Several novel oral anticoagulants have been approved and released on the market as alternatives to warfarin in recent years; in a meta‐analysis, the novel oral anticoagulants significantly reduced stroke/systemic embolic event (SEE), mortality and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), while gastrointestinal bleeding was increased.1 Relative to warfarin, the novel oral anticoagulants have the additional benefit of greater ease of use.

Prior studies have revealed that patients with AF have impaired quality of life (QOL) and that QOL scores are influenced by age, sex, and baseline medical conditions.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Few studies have examined the impact of adverse events such as bleeding on QOL in patients with AF7 and little is known about the impact of different types of bleeding events on QOL, and whether and how that impact changes over time. Insight into the impact of different categories of nonfatal bleeding events on health‐state utility in patients with AF receiving oral anticoagulant therapy may provide a framework to improve understanding of the net clinical benefit and cost‐effectiveness of novel oral anticoagulant therapies relative to warfarin.

The ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation‐Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) Trial was a 3‐arm, randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy trial comparing 2 once‐daily dose regimens of edoxaban (higher dose [60 mg] and lower dose [30 mg]) to warfarin with respect to the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with AF. We used data from ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 to examine the impact of different categories of extracranial bleeding events on health‐state utility scores for patients with AF, and how the impact of bleeding events on health‐state utility changes over time since the event.

Methods

Study Population

The design, methods, and clinical results of the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 trial have been described previously.8, 9 Briefly, patients from 1393 centers in 46 countries were enrolled between November 2008 and November 2010. Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive warfarin, dose‐adjusted to achieve an international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 or to receive higher‐dose 60 mg, or lower‐dose 30‐mg edoxaban regimens; the dose of edoxaban in each arm was reduced by 50% in patients with anticipated increased exposure based on creatinine clearance, body weight, and concomitant permeability glycoprotein inhibitor use. Patients with a high risk of bleeding such as history of prior ICH, major bleeding or peptic ulcer disease within 1 year, hemorrhagic disorders, thrombocytopenia, need for dual antiplatelet therapy, severe renal failure, moderate or severe hepatic insufficiency, active infective endocarditis, uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure >170/100 mm Hg), or recent severe trauma, major surgery, or deep organ biopsy within the previous 10 days, were all excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site, and all patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Quality of Life Assessments

Quality of life was assessed using the self‐administered EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire, which was completed at baseline and at 3‐month intervals for up to 4 years (median 2.8 years) by a subsample of ≈80% of patients from the overall trial population. The EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire is a generic health status measure consisting of 5 domains (mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) that can be converted to utilities using an algorithm developed for the US population.10 Utilities are preference‐based health status measures and range from 0 to 1, with 1 representing perfect health and 0 corresponding to the worst imaginable health state.11 The EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire has been extensively validated and frequently used to assess health‐state utility and health‐related QOL in health economic studies for patients with cardiovascular disease.12 For the purposes of this study, only patients who had baseline and at least 1 follow‐up QOL assessment were included in the study population.

Bleeding End Points

The primary safety end point in ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 was adjudicated major bleeding. Spontaneous bleeding events requiring medical attention were adjudicated by an independent and blinded clinical events committee, according to prespecified criteria as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.13 The specific event categories included major gastrointestinal bleeding, major nongastrointestinal bleeding, and clinically relevant nonmajor (CRNM) bleeding. Major bleeds include symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intraarticular, or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome and/or bleeding causing a decrease in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or more, or leading to transfusion of 2 or more units of whole blood or red blood cells. CRNM bleeds are acute or subacute clinically overt bleeds that do not meet the criteria for major bleed but prompt a clinical response, in that they lead to at least 1 of the following: a hospital admission for bleeding; a physician‐guided medical or surgical treatment for bleeding; or a change in antithrombotic therapy (including interruption or discontinuation of study drug). Bleeding events that did not require medical attention were classified as minor bleeding, without clinical events committee adjudication.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics and QOL scores were compared between patients included versus excluded from this QOL study, and within the QOL study between those with versus without bleeding events, using 2‐sample Student t tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Standardized differences, assuming a threshold of 10% for a clinically meaningful difference,14 were calculated for the comparison of baseline characteristics in the study sample versus those patients excluded from the analysis, in order to evaluate the importance of statistically significant differences given the large sample sizes in both groups.15 Longitudinal mixed effect models were used to examine the impact of different categories of bleeding events on QOL scores by modeling bleeding events as time‐varying covariates.16 These models incorporate all available health status data from all follow‐up time points, and accommodate missing data under the assumption of missing at random. Variables included in the models were baseline QOL score, bleeding status, and time relative to the bleeding event. Linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of follow‐up time were considered, as well as all corresponding interactions between follow‐up time and bleeding status. The interactions between bleeding status and time elapsed since the bleeding events were added to the models to assess any changes in the impact of bleeding events over time. In addition, age, sex, and all other baseline clinical characteristics listed in Table were included in the model development. The models were optimized using a backward selection process and only variables with P<0.1 were retained.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

| Characteristic | Major GI Bleeding | Major Non‐GI Bleedinga | CRNM Bleeding | Minor Bleeding | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event (N=207) | No Eventb (N=9801) | P Value | Event (N=152) | No Eventb (N=9836) | P Value | Event (N=1419) | No Eventb (N=8874) | P Value | Event (N=714) | No Eventb (N=9418) | P Value | |

| Age, y, mean±SD | 74.6±8.6 | 70.3±9.5 | <0.001 | 73.6±8.8 | 70.4±9.5 | <0.001 | 72.1±9.2 | 70.2±9.5 | <0.001 | 72.3±9.2 | 70.3±9.5 | <0.001 |

| Male | 61.4 | 61.5 | 0.974 | 69.7 | 61.4 | 0.035 | 60.2 | 61.7 | 0.291 | 61.9 | 61.4 | 0.777 |

| Previous use of vitamin K antagonist | 64.7 | 58.8 | 0.084 | 64.5 | 58.8 | 0.156 | 62.6 | 58.2 | 0.001 | 67.1 | 58.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 38.2 | 36.6 | 0.639 | 40.8 | 36.5 | 0.281 | 38.3 | 36.4 | 0.159 | 40.9 | 36.3 | 0.014 |

| Dyslipidemia | 57.5 | 54.7 | 0.421 | 58.6 | 54.6 | 0.335 | 58.4 | 54.3 | 0.003 | 65.4 | 54.0 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 95.2 | 95.0 | 0.933 | 95.4 | 95.1 | 0.853 | 93.9 | 95.2 | 0.051 | 94.1 | 95.1 | 0.252 |

| Prior MI | 13.5 | 11.3 | 0.328 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 0.848 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 0.883 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 0.632 |

| Prior stroke | 16.4 | 18.3 | 0.485 | 17.8 | 18.3 | 0.864 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 0.952 | 17.1 | 18.4 | 0.401 |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 11.1 | 12.2 | 0.649 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 0.895 | 13.5 | 12.0 | 0.107 | 14.8 | 12.1 | 0.031 |

| Prior PAD | 7.7 | 4.2 | 0.014 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 0.849 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.996 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 0.503 |

| Congestive heart failure | 61.8 | 60.0 | 0.584 | 48.0 | 60.1 | 0.002 | 51.2 | 61.1 | <0.001 | 47.9 | 60.6 | <0.001 |

| Prior CAD | 38.8 | 33.5 | 0.106 | 37.5 | 33.5 | 0.303 | 35.5 | 33.4 | 0.120 | 35.3 | 33.5 | 0.338 |

| Prior CABG | 14.0 | 7.3 | <0.001 | 13.8 | 7.4 | 0.002 | 10.0 | 7.2 | <0.001 | 14.8 | 7.1 | <0.001 |

| History of ICH bleed | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.000 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.407 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.584 |

| History of non‐ICH bleed | 17.4 | 9.0 | <0.001 | 13.2 | 9.0 | 0.078 | 16.8 | 8.3 | <0.001 | 16.1 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| History of gastrointestinal bleed | 5.8 | 3.0 | 0.018 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 0.225 | 5.1 | 2.8 | <0.001 | 5.3 | 2.9 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance in mg/dL, mean±SD | 69.4±28.4 | 79.1±32.4 | <0.001 | 76.2±38.7 | 78.9±32.2 | 0.307 | 76.1±31.0 | 79.2±32.5 | <0.001 | 76.8±31.1 | 79.1±32.5 | 0.074 |

| CHADS2 score (0–6), mean±SD | 3.0±1.1 | 2.8±1.0 | 0.004 | 2.9±1.0 | 2.9±1.0 | 0.259 | 2.9±1.0 | 2.8±1.0 | 0.386 | 2.9±1.0 | 2.9±1.0 | 0.488 |

| EuroQol‐5D utility, mean±SD | 0.821±0.166 | 0.837±0.152 | 0.147 | 0.843±0.159 | 0.837±0.152 | 0.619 | 0.843±0.147 | 0.836±0.153 | 0.110 | 0.833±0.163 | 0.837±0.152 | 0.522 |

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHADS2, scoring system for the long‐term risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation: acronym stands for Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age≥75y, Diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire; GI, gastrointestinal; ICH intracranial hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Only extracranial bleeds are included.

The sample sizes for the “no event” categories differ according to the category of bleed because of censoring in data selection. All results are % of patients unless otherwise specified.

To avoid potential confounding of other vascular events on the estimated impact of bleeding events on QOL outcomes, patients who experienced any stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, or systemic embolic event were censored on the date of the first thrombotic event. In addition, patients who experienced multiple bleeding events of either the same or different types were censored on the date of the second bleeding event. Any QOL measures on or after the date of censoring were thereby excluded from the analysis.

All analyses were performed using SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a 2‐tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

Results

Patient Population and Baseline QOL

A total of 21 105 patients were enrolled in the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial, of whom 10 706 had baseline and at least 1 follow‐up EQ‐5D collected. Most of the standardized differences between the patients included versus excluded from the QOL study were <10%; only the standardized differences in creatinine clearance, CHADS2 score, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were slightly higher than 10% (Table S1). These results suggest no substantial difference between the 2 cohorts. Patients excluded specifically because of having no follow‐up QOL assessments (n=236) had lower mean baseline EQ‐5D utility scores than those included in the analysis (0.836 versus 0.808, P=0.004); because the analysis adjusts for baseline score, this is unlikely to impact our findings. There were 2492 patients in the QOL study population for whom a spontaneous nonintracranial bleed was reported as a first event; 207 of these were major gastrointestinal bleeds, and 152, 1419, and 714 were major nongastrointestinal, CRNM, and minor bleeds, respectively. One hundred thirty‐seven ICH were observed in the study population, though only 23 of these ICH events were the first event for the patient; therefore, ICH bleed was not analyzed because of small sample size.

For each bleeding category, patients with versus without a bleeding event were older and more likely to have a history of non‐ICH bleeding history and prior coronary artery bypass graft at baseline (Table). Baseline EQ‐5D utility scores did not differ for patients with versus without a bleeding event. Completeness of QOL data collection was high (>90%) throughout the entire study period among the 10 706 patients who were included in this analysis (Table S2), although it tended to be slightly lower for patients with versus without major gastrointestinal bleeding events beginning at the 6‐month follow‐up and thereafter.

Impact of Bleeding on Quality of Life

After adjusting for baseline score and clinical and demographic characteristics, results from the longitudinal mixed effect models revealed that all categories of bleeding events were associated with a significant immediate reduction in EQ‐5D utility (Figure). Major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeding events had similar immediate impacts on utility (−0.029 [95% CI: −0.044–0.014; P<0.001] and −0.029 [95% CI: −0.046 to −0.012; P=0.001], respectively). CRNM and minor bleeding events were associated with smaller but measurable immediate impacts on utility (−0.010 [95% CI: −0.016 to −0.005; P<0.001] and −0.016 [95% CI: −0.024 to −0.008; P<0.001], respectively).

Figure 1.

Estimated impact of bleeding events on EQ‐5D utility. EQ‐5D indicates EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire; GI, gastrointestinal; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor.

Figure demonstrates the estimated impact of bleeding over time, for each of the categories of bleeding events. For major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeds, the impact on utility scores consistently decreased in magnitude over time; while the impact of major nongastrointestinal bleeds was no longer statistically significant at 9 months, the impact of major gastrointestinal bleeds on utility scores remained borderline significantly (−0.011 points, P=0.058) at 12 months. The impacts of CRNM and minor bleeding events on utility were smaller but persisted throughout 12 months with no clear temporal trend.

Discussion

Bleeding is the most common complication associated with anticoagulation management in patients with AF. The frequent (3‐month intervals) assessment of QOL with the EQ‐5D questionnaire in the ENGAGE AF—TIMI 48 trial allowed us to estimate the impact of extracranial bleeding events on health‐state utility over the course of 12 months following the event. All categories of bleeding events were associated with significant immediate decreases in EQ‐5D utility. Compared with CRNM and minor bleeds, major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeds were associated with larger immediate decrements in utility scores that decreased gradually over the year following the bleeding event and were no longer statistically significant at 12 months. In contrast, CRNM and minor bleeding events were associated with smaller but statistically significant initial decreases in utility that persisted for 12 months. The persistence of this decrease is unexpected, and may be because of unmeasured confounding in the population that experiences minor bleeds. The larger relative magnitude of the impact of minor versus CRNM bleeds on utility may be related to the fact that by definition, CRNM bleeding events require some degree of medical intervention, whereas minor bleeding events do not.

To put the estimated immediate disutilities associated with major, CRNM, and minor bleeding events of −0.020, −0.010, and −0.016 from our study in context, a study of complication‐specific changes in utility based on longitudinal data from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus reported decreases in EQ‐5D‐derived utility scores ranging from −0.026, −0.045, and −0.049 for myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and renal failure, to −0.083, −0.099, and −0.122 for blindness, stroke, and amputation, respectively.17 The estimated immediate decreases in EQ‐5D utility scores with bleeding events from our study are comparable to estimates reported in other studies involving other patient populations. For example, using data from the TRANSLATE‐ACS (Treatment With Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Inhibitors: Longitudinal Assessment of Treatment Patterns and Events After Acute Coronary Syndrome) study, Amin et al18 reported that among patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction, bleeding events, classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria, that occurred between discharge and 6 months postacute myocardial infarction were associated with a mean reduction in utility scores of 0.033 points at 6 months. More severe bleeding events (BARC types 3 or 4) were associated with larger decrements in utility (−0.045 points), whereas even minor bleeds (BARC type 1) were associated with smaller but still detectable decreases in utility. A similar finding was observed for patients with acute myocardial infarction with respect to nuisance bleeding, which was found to be independently associated with worse QOL at 1 month.19 Our study is unique, however, given its examination of the trajectory of QOL outcomes over 12 months following the bleeding event. The lack of statistical significance with respect to the estimated utility decrements at 9 months for major nongastrointestinal bleeds and at 12 months for major gastrointestinal and major nongastrointestinal bleeds may be because of the relatively small number of events (207 and 152 major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeds, respectively, as compared with 1419 and 714 CRNM and minor bleeds, respectively) or survivor bias resulting from a higher death rate for patients with more severe bleeds.

These estimates of the pattern of utility changes over time for bleeding events in patients with AF have implications for the estimation of quality‐adjusted life years in cost‐effectiveness studies. In recent years, studies of the cost‐effectiveness of anticoagulation or other approaches to stroke prevention in patients with AF have generally applied utility estimates from a limited number of available sources including the Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study and the national catalog of preference‐based scores for chronic conditions in the United States.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 However, both of these sources are based on data obtained from general community populations, and therefore the utility/disutility estimates may not pertain to patients with AF. Moreover, in cost‐effectiveness analyses, the impact of bleeding events is often assumed to be transient.23, 24, 27 For example, published cost‐effectiveness analyses comparing apixaban and edoxaban versus warfarin assumed disutilities of −0.1511 lasting 2 weeks for major extracranial hemorrhage, −0.0582 lasting 2 days for CRNM bleeds, and −0.013 lasting 2 days for minor bleeds.28, 29 Even with the assumption of no impact on utility beyond 1 year for all categories of extracranial bleeds, results from the current study suggest that disutilities for all categories of bleeds from the patient's perspective may be greater in magnitude than previously assumed. This could have an impact for the evaluation of net clinical benefit, comparative effectiveness, and cost‐effectiveness evaluation of alternative anticoagulation strategies, for which chronic utility and temporary disutility weights are or might be used to combine different clinical events into a common metric.

Results from an analysis of data from the RE‐LY trial examining the impact of therapy with dabigatran versus warfarin on health‐state utility in patients with no major clinical events found no evidence to suggest that the relative complexity and inconveniences of management with warfarin versus dabigatran yielded any measurable decrement in health‐state utility.30 The double‐blind double‐dummy design of the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 trial precluded us from exploring the impact of international normalized ratio monitoring and dose adjustment on QOL in our analysis.

Study Limitations

This study should be considered in light of several important limitations. The ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 trial enrolled subjects with AF at medium or high risk of thromboembolic events, and excluded subjects with AF caused by a reversible disorder, severe renal dysfunction, a high risk of bleeding, and moderate or severe mitral stenosis. Our results may not apply to patients outside of the select enrolled trial population. The EuroQol 5 Dimension questionnaire is a simple, generic health status questionnaire, for which each of the 5 component domains is measured on a 3‐level scale (indicating no problem, some or moderate problem, and extreme problem); as a result it may have limited ability to delineate minor but important clinical differences in health status. Despite adjustment for potential confounders in all models, there remains the possibility of unmeasured confounding. The exclusion of patients with no or limited QOL information might introduce the possibility of selection bias. Since we observed slightly more missing data in patients with a major gastrointestinal bleed, it is possible that the missing data could affect our results if the assumption of missing at random does not hold, though this seems unlikely given the high rate of QOL data collection across all bleeding categories and follow‐up time points. This study considered only the first bleeding event within a patient; thus the results may not accurately relate to the impact of a second bleeding event of either the same or different type on health‐state utility.

Conclusions

In summary, in this large‐scale prospective study of patients with AF, we found that all categories of bleeding events were associated with measurable immediate decreases in health‐state utility. Major gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal bleeds had relatively large immediate decrements, which decreased in magnitude over time and were no longer statistically significant at 12 months. CRNM and minor bleeding events were associated with smaller initial decrements in utility that remained statistically significant and relatively consistent in magnitude through 12 months after the bleeding event. Collectively, these findings have potential use in future studies of the net clinical benefit and cost‐effectiveness of alternative strategies for stroke prevention in patients with AF.

Sources of Funding

The study was funded by a grant from Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.

Disclosures

Dr Kwong is an employee of Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Antman reports receiving grant support through his institution from Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Ruff reports receiving consulting fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim and grant support through his institution from Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Giugliano reports receiving consulting fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Merck; lecture fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, and Sanofi; and grant support through his institution from Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, and AstraZeneca. Dr Cohen reports receiving institutional grant support from Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Magnuson reports receiving institutional grant support and consulting fees from Daiichi Sankyo. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between Patients in the Study Population and Those Excluded From Analysis*

Table S2. Quality of Life Compliance by Bleeding Status

Appendix S1. The Members of the Operations, Executive, Steering, Data Monitoring, Clinical Events Committees, Countries, Participating Centers, Principal Investigators, and Primary Study Coordinators of the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 Trial.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006703 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006703.)28862934

An earlier version of the analysis was presented as a poster at the American Heart Association Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Conference, June 3, 2014 in Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, Camm AJ, Weitz JI, Lewis BS, Parkhomenko A, Yamashita T, Antman EM. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hagens VE, Ranchor AV, Sonderen EV, Bosker HA, Kamp O, Tijssen JG, Kingma JH, Crijns HJ, van Gelder IC; RACE Study Group . Effect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation: results from the rate control versus electrical cardioversion (RACE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thral G, Lane D, Carroll D, Lip GYH. Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2006; 119:448.e1–448.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freeman JV, Simon DN, Go AS, Spertus J, Fonarow GC, Gersh BJ, Hylek EM, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Thomas LE, Chang P, Peterson ED, Piccini JP. Association between atrial fibrillation symptoms, quality of life, and patient outcomes results from the outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation (ORBIT‐AF). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reynolds MR, Lavelle T, Essebag V, Cohen DJ, Zimetbaum P. Influence of age, sex, and atrial fibrillation recurrence on quality of life outcomes in a population of patients with new‐onset atrial fibrillation: the Fibrillation Registry Assessing Costs, Therapies, Adverse events and Lifestyle (FRACTAL) study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reynolds MR, Ellis E, Zimetbaum P. Quality of life in atrial fibrillation: measurement tools and impact of interventions. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:762–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lancaster TR, Singer DE, Sheehan MA, Oertel LB, Maraventano SW, Hughes RA, Kistler P. The impact of long‐term warfarin therapy on quality of life: evidence from a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1944–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, Crugnale SE, Bocanegra T, Mercuri M, Hanyok J, Patel I, Shi M, Salazar D, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Evaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: design and rationale for the Effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation‐Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48). Am Heart J. 2010;160:635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Phil D, Weitz JI, Spinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The EuroQol Group . Euro‐Qol: a new facility for measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal. J Health Econ. 1986;5:1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using EQ‐5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non‐surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavior Sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects implications for managed care. P T. 2008;33:700–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayes A, Arima H, Woodward M, Chalmers J, Poultzer N, Hamet P, Clarke P. Changes in quality of life associated with complications of diabetes: results from the ADVANCE study. Value Health. 2016;19:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amin AP, Wang TY, McCoy L, Bach RG, Effron MB, Peterson ED, Cohen DJ. Impact of bleeding on quality of life in patients on DAPT: insights from TRANSLATE‐ACS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:59–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amin AP, Bachuwar A, Reid KJ, Chhatriwalla AK, Salisbury AC, Yeh RW, Kosiborod M, Wang TY, Alexander KP, Gosch K, Cohen DJ, Spertus JA, Bach RG. Nuisance bleeding with prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy after acute myocardial infarction and its impact on health status. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2130–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrington AR, Armstrong EP, Nolan PE, Malone DC. Cost‐effectiveness of apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2013;44:1676–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Obrien CL, Gage BF. Costs and effectiveness of ximelagatran for stroke prophylaxis in chronic atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2005;293:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canestaro WJ, Patrick AR, Avorn J, Ito K, Matlin OS, Brennan TA, Shrank WH, Choudhy NK. Cost‐effectiveness of oral anticoagulants for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sullivan PW, Arant TW, Ellis SL, Ulrich H. The cost effectiveness of anticoagulation management services for patients with atrial fibrillation and at high risk of stroke in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:1021–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Freeman JV, Zhu RP, Owens DK, Garber AM, Hutton DW, Go AS, Wang PJ, Turakhia MP. Cost‐effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Dorn N, Peterson K, Martin PA. The Beaver Dam health Outcomes Study: initial catalog of health‐state quality factors. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V. A national catalog of preference‐based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Care. 2005;43:736–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coyle D, Coyle K, Cameron C, Lee K, Kelly S, Steiner S, Wells GA. Cost‐effectiveness of new oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in preventing stroke and other cardiovascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation. Value Health. 2013;16:498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magnuson EA, Vilain K, Wang K, Li H, Kwong WJ, Antman EM, Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Cohen DJ. Cost‐effectiveness of edoxaban vs warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation based on results of the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170:1140–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dorian P, Kongnakorn T, Phatak H, Rublee DA, Kuznik A, Lanitis T, Liu LZ, Iloeje U, Hernandez L, Lip GYH. Cost‐effectiveness of apixaban vs. current standard of care for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1897–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monz BU, Connolly SH, Korhonen M, Noack H, Pooley J. Assessing the impact of dabigartran and warfarin on health‐related quality of life: results from an RE‐LY sub‐study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between Patients in the Study Population and Those Excluded From Analysis*

Table S2. Quality of Life Compliance by Bleeding Status

Appendix S1. The Members of the Operations, Executive, Steering, Data Monitoring, Clinical Events Committees, Countries, Participating Centers, Principal Investigators, and Primary Study Coordinators of the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 Trial.