Abstract

Background and objectives

A geriatric assessment is an appropriate method for identifying frail elderly patients. In CKD, it may contribute to optimize personalized care. However, a geriatric assessment is time consuming. The purpose of our study was to compare easy to apply frailty screening tools with the geriatric assessment in patients eligible for dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A total of 123 patients on incident dialysis ≥65 years old were included <3 weeks before to ≤2 weeks after dialysis initiation, and all underwent a geriatric assessment. Patients with impairment in two or more geriatric domains on the geriatric assessment were considered frail. The diagnostic abilities of six frailty screening tools were compared with the geriatric assessment: the Fried Frailty Index, the Groningen Frailty Indicator, Geriatric8, the Identification of Seniors at Risk, the Hospital Safety Program, and the clinical judgment of the nephrologist. Outcome measures were sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

Results

In total, 75% of patients were frail according to the geriatric assessment. Sensitivity of frailty screening tools ranged from 48% (Fried Frailty Index) to 88% (Geriatric8). The discriminating features of the clinical judgment were comparable with the other screening tools. The Identification of Seniors at Risk screening tool had the best discriminating abilities, with a sensitivity of 74%, a specificity of 80%, a positive predictive value of 91%, and a negative predictive value of 52%. The negative predictive value was poor for all tools, which means that almost one half of the patients screened as fit (nonfrail) had two or more geriatric impairments on the geriatric assessment.

Conclusions

All frailty screening tools are able to detect geriatric impairment in elderly patients eligible for dialysis. However, all applied screening tools, including the judgment of the nephrologist, lack the discriminating abilities to adequately rule out frailty compared with a geriatric assessment.

Keywords: dialysis; elderly; frailty; geriatric assessment; screening; Aged; Frail Elderly; Geriatric Assessment; Humans; Judgment; Nephrologists; Outcome Assessment (Health Care); renal dialysis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Risk; Safety; Sensitivity

Introduction

Worldwide, the incidence of ESRD in the elderly has risen in the past decades (1). This has resulted in a growing number of elderly patients starting dialysis (2). A substantial proportion of these patients exhibits functional and cognitive impairment (3,4) or will experience loss of personal independence within the first months to years on dialysis (5). These aspects affect quality of life and may lead to higher hospitalization rates and mortality rates (6). Furthermore, retrospective research in the elderly population (≥75 years old) with multiple comorbidities has shown no survival benefit of dialysis compared with conservative care (7–9). It is difficult to estimate upfront which elderly patients will benefit from dialysis initiation and for which vulnerable patients existence on dialysis will be challenging (10).

Emerging evidence exists on the role of frailty as a measurement for the heterogeneity of ageing in CKD (11,12). The phenotype of frailty is characterized by generalized decline in multiple physiologic systems, with exhaustion of functional reserves and vulnerability to a range of adverse outcomes, including disability (13). In patients eligible for dialysis, frailty is associated with poor survival (14,15). A prognostic evaluation of frailty may improve patient-centered care and decision making in ESRD (16).

There is general consensus that a geriatric assessment is the best systematic approach for the identification of frailty in clinical practice (17–19). The geriatric assessment is a multidimensional approach to evaluate the health status of elderly patients regarding somatic, functional, and psychosocial domains in a systematic and evidenced-based way (20). Components that it should consist of are (instrumental) activities of daily living; sensory deficits; mobility, including falls; mood and cognition; nutrition; comorbidity; polypharmacy; and social support. It can help to detect underlying geriatric impairment, which would otherwise be overlooked in seemingly fit patients. Additionally, it can form a starting point for personalized interventions to optimize the patients’ independence (21,22). In other fields of medicine, a geriatric assessment has shown to optimize treatment decisions, thereby improving quality of life (20,23,24).

An evaluation of patients with ESRD by means of a geriatric assessment has been suggested for improving informed decision making concerning dialysis initiation as well (25). A disadvantage is that it can be time consuming, and many fit elderly may undergo a full evaluation unnecessarily. Applying a short frailty screening tool could form a first step in selecting patients who would benefit most from a more comprehensive geriatric evaluation (19). Several frailty screening tools exist, of which the clinical overt disability in physical performance on the basis of the Fried criteria has been most frequently used in dialysis (26). An ideal screening tool for geriatric impairment in this setting should have a high sensitivity, which ensures that actually frail patients will be screened as frail, and sufficient specificity, so that the time-consuming process of a full geriatric assessment is optimally used.

In this analysis of the Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients Starting Dialysis (GOLD) Study, we have assessed the discriminating abilities of several screening instruments for detecting frailty in elderly patients eligible for dialysis compared with a more comprehensive geriatric assessment. For this analysis, we use the baseline results of the GOLD Study.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

These analyses include the baseline characteristics of the GOLD Study, a multicenter, prospective, cohort study assessing the relation between a geriatric assessment and poor outcome in patients with ESRD. All patients included in the GOLD Study were included in these analyses, except for patients who received conservative therapy. Participants were enrolled from 17 different hospitals across The Netherlands (Supplemental Appendix 1) in the period from August of 2014 to August of 2016. Consecutive patients eligible for dialysis were included between 3 weeks before and 2 weeks after the first dialysis session. Patients were excluded if informed consent was not provided, if they had insufficient understanding of the Dutch language, or if they suffered from a terminal nonrenal-related condition. If applicable, the caregiver of each patient was asked to participate as well. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the medical ethics review boards of all participating hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and participating caregivers before enrollment.

Data Collection and Analyses

Baseline demographic data collected from the medical charts and during the geriatric assessment included age, sex, education level, and living situation. Other clinical characteristics included cause of kidney failure, type of dialysis, acute or planned start of dialysis, BP, body mass index, and smoking habit.

For the geriatric assessment, participants were either visited at home (on a nondialysis day for patients on hemodialysis) or in the dialysis center before starting the dialysis session. The assessments were performed by the primary investigator (I.N.v.L.) or one of the trained research nurses. The geriatric assessment consisted of validated questionnaires or a structured assessment of the following seven domains (Tables 1 and 2): activities of daily living (Katz et al. [27]), instrumental activities of daily living (Lawton and Brody [28]), mobility (Timed-Up-and-Go [29]; the average of three measurements was recorded), depressive symptoms (the Geriatric Depression Scale [30]), nutrition (the Mini Nutritional Assessment [31]), comorbidity burden (the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics [32]), and cognition. The cognitive test battery consisted of four tests: the Mini Mental State Examination (33), the Enhanced Cued Recall (34), the Clock drawing test (35), and fluency (36). Cognitive impairment was defined as one or more abnormal cognitive test scores.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of elderly patients on incident dialysis (the Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients Starting Dialysis Study)

| Baseline characteristics | All, n=123 | Frail, n=92; 75% | Fit, n=31; 25% | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr | 76 (±7) | 76 (±7) | 74 (±7) | 0.28 |

| Sex (men), % | 64 | 60 | 77 | 0.08 |

| Single status/widow(er), % | 37 | 40 | 29 | 0.26 |

| Living in nursing home facility, % | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0.11 |

| University level of education, % | 21 | 19 | 29 | 0.22 |

| Cause of kidney failure, % | 0.16 | |||

| Vascular | 50 | 53 | 39 | |

| Diabetes | 19 | 20 | 16 | |

| GN | 3 | 2 | 7 | |

| Interstitial nephropathy | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Polycystic | 2 | 0 | 10 | |

| Other | 11 | 11 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 11 | 13 | |

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| Treatment modality hemodialysis, % | 76 | 79 | 68 | 0.10 |

| Acute-start dialysis, % | 23 | 28 | 6 | 0.01 |

| Systole, mmHg | 149 (±22) | 148 (±23) | 149 (±19) | 0.70 |

| Diastole, mmHg | 74 (±14) | 74 (±15) | 76 (±10) | 0.57 |

| Body mass index | 27 (±6) | 27 (±6) | 27 (±3) | 0.90 |

| Current or former smoker, % | 75 | 73 | 79 | 0.58 |

Mean (±SD).

Table 2.

Domains incorporated in the geriatric assessment and prevalence of impaired domains

| Domain, Test, and Category | Range | Cutoff | Source | Impairment,a % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL | ||||

| Katz scale | 1–6 | ≥1 | Patient | 34 (n=42) |

| iADL | ||||

| Lawton and Brody | 1–7 | ≥1b | Patient | 78 (n=96) |

| Mobility | Patient | |||

| Timed-Up-and-Go | ||||

| No impairment | <10 s | 37 (n=45) | ||

| Moderate | 10–20 s | 39 (n=48) | ||

| Severe | >20 s | 25 (n=30) | ||

| Cognitive impairment | Patient | |||

| MMSE | 0–30 | <25 | 12 (n=15) | |

| Clock | 0–14 | ≤10 | 45 (n=55) | |

| ECR | 0–16 | <14 | 13 (n=16) | |

| Fluency | 0–40 | <15c | 39 (n=48) | |

| ≥1 Domain | 66d (n=81) | |||

| Depressive symptoms | Patient | |||

| GDS | ||||

| No impairment | 0–15 | <5 | 69 (n=85) | |

| Mild symptoms | 5–10 | 27 (n=33) | ||

| Severe symptoms | >10 | 4d (n=5) | ||

| Malnutrition | Patient | |||

| MNA | ||||

| No malnutrition | 0–30 | 24–30 | 45 (n=55) | |

| Risk of malnutrition | 17–23.5 | 50 (n=62) | ||

| Malnutrition | 0–17 | 6d (n=7) | ||

| Comorbidities | Chart | |||

| CIRS-G | ||||

| Severee | 0–12 | 35 (n=43) | ||

| Frailty | ||||

| Geriatric assessment | ||||

| ≥2 Geriatric impairmentsf | 0–7 | ≥2 | 75 (n=92) |

ADL, activities of daily living; iADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; ECR, Enhanced Cued Recall; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; CIRS-G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics.

Impairment: percentage of patients who scored below/above the cutoff value.

One or more impairment in iADL.

Less than 15 words.

Category used to calculate frailty.

CIRS-G≥2×score 3 or ≥1×score 4 (i)ADL (instrumental) activities of daily living.

Impairment in (i)ADL, severe mobility impairment, impairment in greater than or equal to cognitive domain, severe depressive symptoms, malnutrition, and severe comorbidity score.

The outcome of the geriatric assessment was composed by the sum of impairment in the seven geriatric domains: thus, a minimum score of zero points and a maximum of seven points could be obtained. Patients with impairment in two or more domains were considered frail (24).

In addition to the geriatric assessment, six different frailty screening tools were applied: the Groningen Frailty Indicator (37), the Fried Frailty Index, Geriatric8 (38), the Identification of Seniors at Risk-Hospitalized Patients screening (39), the Hospital Safety Program criteria (Veiligheidsmanagementsysteem; the elderly-specific component of the nationally implemented safety program) (40), and the clinical judgment of the nephrologist (frailty question). Because there is no consensus on the definition of frailty, we included several frailty screening tools that incorporate different aspects of frailty (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Discriminating test characteristics of all frailty measurements used in the Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients Starting Dialysis Study and the prevalence of frailty according the tests

| Screening Modality | Cutoff Value | Prevalence of Frailty, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fried Frailty Index | ≥3 | 48 | 59 (48–70) | 85 (66–96) | 92 (83–97) | 41 (34–49) |

| Groningen Frailty Indicator | ≥4 | 67 | 74 (64–83) | 52 (33–70) | 82 (76–87) | 40 (29–52) |

| G8 | ≤14 | 88 | 92 (85–97) | 26 (12–45) | 79 (75–82) | 53 (31–74) |

| ISAR-HP | ≥2 | 60 | 72 (61–81) | 79 (59–92) | 91 (83–96) | 48 (38–58) |

| VMS vulnerable elderly | ≥2 | 82 | 90 (79–96) | 38 (19–59) | 78 (72–83) | 60 (37–79) |

| Frailty question | ≥5 | 63 | 72 (61–82) | 67 (45–84) | 88 (80–93) | 42 (32–53) |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; G8, Geriatric8; ISAR-HP, Identification of Seniors at Risk-Hospitalized Patients; VMS, Veiligheidsmanagementsysteem (Hospital Safety Program criteria); frailty question, clinical judgment of the nephrologist.

Table 4.

Similarities between frailty screening instruments and geriatric assessment: percentage of questions addressing a geriatric issue

| Geriatric domain | GA, % | Fried, % | GFI, % | G8, % | ISAR-HP, % | VMS, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL | 14 | — | 13 | — | — | 25 |

| iADL | 14 | — | 7 | — | 50 | — |

| Mobility/physical performance/falls | 14 | 60 | 7 | 12 | 25 | 25 |

| Cognition | 14 | — | 7 | 12a | — | 25 |

| Mood | 14 | — | 33 | 12a | — | — |

| Malnutrition | 14 | 20 | 7 | 47 | — | 25 |

| Comorbidity | 14 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other items of the frailty measurements | ||||||

| Neurosensory impairmentb | — | — | 13 | — | — | — |

| General health | — | 20 | 7 | 12 | — | — |

| Polypharmacyc | — | — | 7 | 6 | — | — |

| Aged | — | — | — | 12 | — | — |

| Low educational level | 25 |

GA, Geriatric Assessment; Fried, Fried Frailty Index; GFI, Groningen Frailty Indicator; G8, Geriatric8; ISAR-HP, Identification of Seniors at Risk-Hospitalized Patients; VMS, Veiligheidsmanagementsysteem (Hospital Safety Program criteria); ADL, activities of daily living; —, no similarity; iADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Cognitive impairment or mood disturbances.

Hearing or vision loss.

>3 medications.

<80, 80-85, >85.

For the clinical judgment, the treating physician was asked to indicate how frail the patient was in his/her opinion on a scale from zero to ten, where zero was fit and ten was frail. A score of greater than or equal to five was a priori defined as frail. The details of the frailty screening tools can be found in Supplemental Appendix 2. For the Fried Frailty Index, maximal grip strength (best of three measurements) was measured in the dominant hand using an electronic hand dynamometer (Model EH101), and walking speed was measured as the fastest time of two measurements. Four screening tools were included in the initial data collection (the Groningen Frailty Indicator, the Fried Frailty Index, Geriatric8, and the frailty question), whereas two screening tools were constructed on the basis of the collected data (the Hospital Safety Program and the Identification of Seniors at Risk-Hospitalized Patients screening).

Statistical Analyses

The discriminative value of the six frailty screening modalities was assessed by comparing them with the outcome of the geriatric assessment. Differences between fit and frail patients on the basis of the geriatric assessment were assessed with chi-squared tests for categorical variables and paired t tests for continuous variables if normally distributed or Mann–Whitney U tests in non-normally distributed variables. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values were calculated using the outcome of two or more impaired domains of the geriatric assessment as the reference test (Table 3).

Data analysis was performed with SPSS version 22 software (15). A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The analysis included 123 consecutive elderly patients starting dialysis. The 54 patients treated with conservative care were not included. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics. Mean age was 76 (±7) years old, and 64% of the patients were men; 76% of patients started hemodialysis, and 24% started peritoneal dialysis.

Geriatric Impairment

Table 2 shows the proportion of patients experiencing impairment across each of the geriatric domains as identified with the geriatric assessment. In this population, functional impairment was high: 78% needed help with instrumental activities of daily life, 34% needed help with basic activities of daily living, and in 25% of patients, mobility was severely impaired. Cognitive impairment (impairment of one or more cognitive domains) was present in 66% of patients. Severe comorbidity burden (in addition to kidney failure) was found in 35% of patients. The risk of severe malnutrition and prevalence of severe depressive symptoms were low: 6% and 4%, respectively. However, risk of malnutrition reached 50%, and 27% of patients showed mild depressive symptoms.

Of all patients, 75% (n=92) had impairment in two or more domains and were considered frail. As shown in Table 1, frail patients did not differ from fit patients in age and treatment modality. In the frail group, more patients started acutely with dialysis (instead of planned) compared with in the fit group (28% versus 6%; P=0.01).

Screening Instruments

The prevalence of frailty differed widely according to the different frailty screening tools as shown in Table 3. The lowest percentage of frailty was found with the Fried Frailty Index (48%), and the highest percentage was with Geriatric8 (88%).

As can be seen in Table 4, the different tools focus on different aspects of frailty and allocate a different weight to the various items. Some additional items, such as age, general health, polypharmacy, educational level, and neurosensory impairment, are incorporated in one or more screening tools, whereas they are not part of the geriatric assessment. The Fried Frailty Index is the only screening tool using objective measurements (handgrip strength and walking speed); the other tools use only self-reported items.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of each of the six frailty screening tools for impaired geriatric assessment (two or more impaired domains) are listed in Table 3, and the absolute numbers can be found in Supplemental Appendix 3. Sensitivity for impaired geriatric assessment was highest for Geriatric8 (92%). However, only 12% of all patients were scored as fit, which resulted in low specificity (26%).

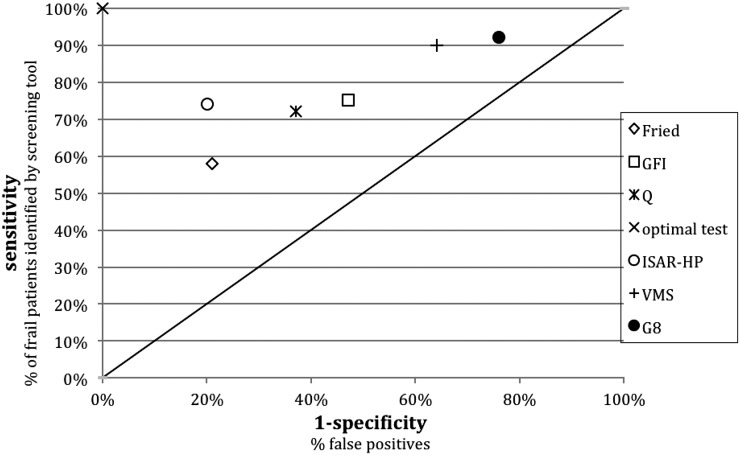

Figure 1 shows the relationship between sensitivity and false positives (1 − specificity). Optimal test characteristics of a screening instrument would be a 0% false positive score (100% specificity; x axis) and a 100% sensitivity (y axis), represented by the X in Figure 1. The diagonal line represents a random guess (i.e., 50:50 chance), which would not be discriminative at all. The Identification of Seniors at Risk most closely approximates the left upper corner, with a high specificity (79%) and a fairly good sensitivity (72%). The positive predictive value of the Identification of Seniors at Risk was high (91%). This resulted in six of 68 patients being incorrectly screened as potentially frail. However, the negative predictive value was low for this tool (48%), meaning that 24 of 46 patients were misidentified and considered fit while having two or more impaired geriatric domains (Supplemental Appendix 3). The differences between the tools were small, and none of the tests scored >60% for their negative predictive value. The discriminating abilities of the tools did not improve when we compared them with three or more impairments on the geriatric assessment (Supplemental Appendix 4).

Figure 1.

Frailty screenings tools compared with the geriatric assessment (two or more impairments). Diagonal represents a random guess (i.e., 50–50 chance). Fried, Fried Frailty Index; G8, Geriatric8; GFI, Groningen Frailty Indicator; ISAR-HP, Identification of Seniors at Risk-Hospitalized Patients; Q, frailty question; VMS, Veiligheidsmanagementsysteem (Hospital Safety Program criteria).

The clinical judgment of the nephrologist, the frailty question, had moderate discriminating ability for geriatric impairment compared with the five frailty screening tools.

Discussion

This cross-sectional analysis of elderly patients enrolled in the GOLD Study shows that geriatric impairment is highly prevalent at the time of dialysis initiation, with 78% of patients showing functional dependency (impairment in instrumental activities of daily living) and 66% showing cognitive impairment. Three quarters of the study population (75%) had significant impairment in two or more geriatric domains and were considered frail. Because a geriatric assessment can be time consuming, we set out to compare frailty screening tools that can select those patients who could benefit from a more comprehensive geriatric assessment in the context of decision making concerning dialysis initiation. High sensitivity is important for this approach, which ensures that frail patients will accurately be screened as frail. In addition, specificity should be adequate, because an overinclusive measure will not save time. Only Geriatric8 and the Hospital Safety Program criteria stand out for having a good sensitivity, but both lack discriminative abilities; using Geriatric8 as an initial screening tool would select 88% of all patients for a time-consuming geriatric assessment, whereas in only 75% of patients, two or more impaired domains will be found. Because Geriatrc8 is not sufficiently discriminative here, using this tool is not sensible when there is a scarcity of resources to perform a geriatric assessment. Of the frailty screening tools, the Identification of Seniors at Risk has the best discriminating abilities in the ESRD population, showing the highest specificity and a fairly good sensitivity, and 91% of patients with a positive Identification of Seniors at Risk are frail according to the geriatric assessment (high positive predictive value). However, the negative predictive value is poor (48%). Consequently, more than one half of the patients who are screened as fit will, in fact, have two or more impairments on the geriatric assessment, and a negative frailty screening cannot be used to adequately rule out frailty. In conclusion, frailty screening instruments do not seem to be particularly helpful in preselecting frail patients who may benefit from an additional geriatric evaluation process.

Another observation that arises from these data is that the discriminating features of clinical judgment (frailty question) are comparable with the screening tools. Thus, the gut feeling of the nephrologist seems to be as useful as a screening tool to detect geriatric impairment. How valuable the clinical judgment is in detecting vulnerable patients at risk for poor outcome was illustrated before by the surprise question: “would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” The odds of dying were 3.5 if the answer was no (95% confidence interval, 1.36 to 9.07) compared with yes (41). Nonetheless, as can be observed from the low negative predictive value, clinical judgment detects vulnerable patients but will still overlook a large population in whom geriatric impairment exists.

With the increase in the elderly ESRD population, the need for evidence to support the decision-making progress increases. Several studies assessed the potential of screening instruments for distinguishing between fit patients eligible for dialysis and patients in whom the burdens of dialysis may not outweigh the benefits and for whom conservative care should be discussed more extensively as an alternative option. Multiple risk stratification algorithms have been developed for (short-term) mortality, incorporating laboratory data and comorbidity burden (25,42–44). Presence of functional impairment is scored as well but only to a limited extent. Because functional impairment together with impairment in other geriatric domains influence quality of life, these mortality risk models may not suffice as a screening tool for identifying high-risk patients, because they lack sufficient information to support shared decision making concerning dialysis initiation (10). An advantage of an initial frailty screening may be that it does not only detect patients at risk for poor outcome (14) but it additionally identifies patients with potential geriatric impairment who may benefit from a subsequent comprehensive assessment and geriatric rehabilitation.

The workup of a frailty screening instrument followed by a geriatric assessment in the process of shared decision making in elderly patients is increasingly used in daily practice (45). However, reports on comparison of different frailty tools in patients on dialysis are sparse. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the discriminating abilities of frailty screening tools in the incident dialysis population. Johansen et al. (46) compared two frailty definitions, performance based and self-reported function, based in patients on prevalent hemodialysis from the US Renal Data System. Frailty was prevalent in 31% according to the performance-based definition and 52% according to the self-reported definition, and 27% of patients were frail according to both definitions. Both frailty tests were associated with mortality, with patients who met both definitions having the highest mortality risk (hazard ratio, 2.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.51 to 4.01). No comparison was made with a more comprehensive geriatric assessment. In one small report, the Groningen Frailty Indicator was applied in patients with ESRD (n=65), and frail patients (Groningen Frailty Indicator ≥4) were referred to a geriatrician for additional assessment. Over one half of geriatric problems detected by the geriatrician were not reported in the nephrologists’ notes. The problems that were overlooked mainly concerned mental health, cognition, and neurosensory deficits. No sensitivity/specificity analysis could be performed (47). Another report comparing the Groningen Frailty Indicator, the Identification of Seniors at Risk, and the Hospital Safety Program criteria with an extended Fried Frailty Index as a gold standard showed a comparable performance for the Groningen Frailty Indicator and the Identification of Seniors at Risk in a heterogeneous group (n=95) of patients who were predialysis and patients established on dialysis (45). In geriatric oncology, the use of screening tools to assess functional reserves before the start of chemotherapy is more common practice. However, in this population, screening tools lacked the discriminating abilities to select patients in the oncology department for further geriatric evaluation as well (19).

Although its importance has been recognized in CKD (14,15), thus far, no consensus exists on the definition of frailty and the components of which it consists (48). Assessment of frailty in ESRD mainly focuses on overt clinical disability on the basis of the Fried criteria, which include poor endurance, muscle weakness, and malnutrition. However, because frailty is a phenotype of decreased physiologic reserve and multisystem dysregulation associated with increased vulnerability to stressors (13), cognitive and psychosocial issues may contribute as well and should not be ignored (48).

In addition, the cutoff value of two or more geriatric impairments of the geriatric assessment is arbitrary. However, previous research showed that the risk of disability and mortality was higher in patients meeting a cutoff score of two or more geriatric impairments (49,50). If we change the cutoff value for frailty in our study to three or more impairments, the prevalence of frailty would decrease to 44%. Overall, the discriminating abilities of the tests do not improve. In addition, using a combination of two frailty screening tools does not lead to better discriminating abilities, because sensitivity increases but specificity decreases (data not shown). Future research should focus on establishing greater uniformity in the cutoff values and the content of a geriatric assessment to allow for a better comparison.

Predictive values are related to the prevalence of the outcome. Consequently, in a population in which frailty would be less prevalent, the screening tools would have a lower positive predictive value. The prevalence of frailty in our study is comparable with that in two other studies in patients on incident dialysis (68% and 73%) (14,15). Both studies used a modified definition of the Fried Frailty Index. Even in young patients, the prevalence of frailty was found to be high (40%) (15). Therefore, the generalizability of the predictive values of the screening tests in general is good. As in our study, impairment in instrumental activities of daily living is the most frequently encountered geriatric impairment (78%); the Identification of Seniors at Risk, which has a particular focus on instrumental activities of daily living, has the best positive predictive value of all tools. Because the Fried Frailty Index focuses on the physical performance phenotype exclusively, it is not surprising that sensitivity for frailty according to the multidimensional geriatric assessment is poor. However, tools that incorporate a wider range of geriatric impairments (Table 4) lack specificity.

This is a unique cohort of patients on incident dialysis undergoing a geriatric assessment. However, there are some limitations. First, it is a selected cohort, in which the decision to start dialysis has already been made. Although it is likely that the discriminating abilities of the frailty screening tools for geriatric impairment are comparable for elderly patients who choose conservative therapy and may exhibit a higher burden of geriatric impairment, data are currently lacking. Second, the frailty question is not a validated test but merely a Visual Analog Scale to objectify the clinical judgment of the physician on frailty. The cutoff value was predefined, but this was not on the basis of available evidence, because this approach has not been used before. Thus, such a screening method should be used with caution in clinical practice. Third, a geriatric assessment such as that used in this study is not a replacement for a consultation with a geriatrician, and detection of depressive symptoms with the geriatric depression scale is not comparable with a full psychologic examination. Also, there is a great deal of variation in the way that geriatric assessments are conducted. Several combinations of tools and various models are available for implementation of geriatric assessment; in oncology practice, an expert panel could not endorse one over another (20). The use of a uniform assessment would enhance comparability in clinical research. Fourth, although emerging evidence exists on the predictive value of a geriatric assessment in decision making in elderly patients in other fields of medicine (24,20), the relation between a geriatric assessment and poor outcome after dialysis initiation has not been fully established yet. However, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial geriatric impairments were shown to be related to mortality and hospitalizations (6). This will be the subject of the longitudinal analysis of the GOLD Study.

A geriatric assessment may fill a knowledge gap in optimizing personalized care in elderly patients, but a large disadvantage is that it can be time consuming. A screening tool preceding a geriatric assessment, identifying the potentially frail patients who would actually benefit from this comprehensive assessment, would be useful. We have shown that screening tools are able to detect geriatric impairment in patients eligible for dialysis. The vast majority of the appointed patients are genuinely frail and could benefit from a long-term care plan and additional attention to help improve or maintain functional and psychosocial abilities. However, all applied screening tools lack the discriminating abilities to adequately rule out frailty compared with a geriatric assessment. Although the clinical judgment of the nephrologist performs similarly to the screening tools, it does not adequately select patients with or without geriatric impairment. Almost one half of the patients screened as fit did have a considerable number of geriatric impairments. Frailty screening tools could be used as a first step to detect frailty, but future research should focus on establishing a more reliable preselection method for elderly patients who could benefit from a more comprehensive geriatric assessment.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients and medical staff who participated in this project.

This work was made possible by the Cornelis de Visser Stichting, Stichting Medicina et Scientia, and AstraZenica.

The funding sources had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, interpretation, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients Starting Dialysis Study Investigators: Dianet Dialysis Center: F.T.J.B.; Diakonessenhuis Utrecht: M.E.H.; University Medical Center Utrecht: A.C. Abrahams, M.L.B., and M.C.V.; St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein: H.H. Vincent; Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem: C.E. Douma, C. Verburg; Bernhoven Hospital, Uden: J. Lips; Gelderse Vallei Hospital, Ede: M.A. Siezenga; Ter Gooi Hospital, Hilversum: L.E. Gamadia; Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam: I. Keur; Zaans Medical Center, Zaandam: R.J.L. Klaassen; Jeroen Bosch Hospital, Hertogenbosch: E.K. Hoogeveen; Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht: E.F.H. van Bommel; St. Franciscus Hospital, Rotterdam: Y.C. Schrama; Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam: P.J.G. van de Ven; and Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda: J.W. Eijgenraam.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11801116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System: Atlas of ESRD, Vol. 2, Chapter 1, incidence prevalence patient characteristics and modality. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/2012/view/v2_01.aspx. Accessed August 22, 2016

- 2.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook WL, Jassal SV: Functional dependencies among the elderly on hemodialysis. Kidney Int 73: 1289–1295, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray AM, Knopman DS: Cognitive impairment in CKD: No longer an occult burden. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 615–618, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Loon IN, Wouters TR, Boereboom FT, Bots ML, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME: The relevance of geriatric impairments in patients starting dialysis: A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1245–1259, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A: Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1611–1619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ: Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 633–640, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couchoud C, Hemmelgarn B, Kotanko P, Germain MJ, Moranne O, Davison SN: Supportive care: Time to change our prognostic tools and their use in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1892–1901, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swidler M: Considerations in starting a patient with advanced frailty on dialysis: Complex biology meets challenging ethics. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1421–1428, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roshanravan B, Khatri M, Robinson-Cohen C, Levin G, Patel KV, de Boer IH, Seliger S, Ruzinski J, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum B: A prospective study of frailty in nephrology-referred patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 912–921, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group : Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: M146–M156, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG: Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2960–2967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL: Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 172: 1071–1077, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, Boyarsky B, Gimenez L, Jaar BG, Walston JD, Segev DL: Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 896–901, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajabali N, Rolfson D, Bagshaw SM: Assessment and utility of frailty measures in critical illness, cardiology, and cardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol 32: 1157–1165, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogendijk EO, van der Horst HE, Deeg DJ, Frijters DH, Prins BA, Jansen AP, Nijpels G, van Hout HP: The identification of frail older adults in primary care: Comparing the accuracy of five simple instruments. Age Ageing 42: 262–265, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC: Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol 13: e437–e444, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M, Falandry C, Artz A, Brain E, Colloca G, Flamaing J, Karnakis T, Kenis C, Audisio RA, Mohile S, Repetto L, Van Leeuwen B, Milisen K, Hurria A: International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32: 2595–2603, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jassal SV: Geriatric assessment, falls and rehabilitation in patients starting or established on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 35: 630–634, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gambert SR: Comprehensive geriatric assessment: A multidimensional process designed to assess an elderly person’s functional ability, physical health, cognitive and mental health, and socio-environmental situation. Available at https://www.asn-online.org/education/distancelearning/curricula/geriatrics/. Accessed September 1, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilotto A, Cella A, Pilotto A, Daragjati J, Veronese N, Musacchio C, Mello AM, Logroscino G, Padovani A, Prete C, Panza F: Three decades of comprehensive geriatric assessment: Evidence coming from different healthcare settings and specific clinical conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18: 192.e1–192.e11, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamaker ME, Schiphorst AH, ten Bokkel Huinink D, Schaar C, van Munster BC: The effect of a geriatric evaluation on treatment decisions for older cancer patients--A systematic review. Acta Oncol 53: 289–296, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couchoud CG, Beuscart JB, Aldigier JC, Brunet PJ, Moranne OP, Registry REIN: Development of a risk stratification algorithm to improve patient-centered care and decision making for incident elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 88: 1178–1186, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohm C, Storsley L, Tangri N: The assessment of frailty in older people with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24: 498–504, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW: Studies of illness in the aged. The index of adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185: 914–919, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9: 179–186, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S: The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39: 142–148, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman B, Heisel MJ, Delavan RL: Psychometric properties of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in functionally impaired, cognitively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1570–1576, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, Nourhashemi F, Bennahum D, Lauque S, Albarede J: The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition 15: 116–122, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M, Tomlinson G, Naglie G, Cook WL, Jassal SV: Geriatric comorbidities, such as falls, confer an independent mortality risk to elderly dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1396–1400, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saka E, Mihci E, Topcuoglu MA, Balkan S: Enhanced cued recall has a high utility as a screening test in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in Turkish people. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 21: 745–751, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sunderland T, Hill JL, Mellow AM, Lawlor BA, Gundersheimer J, Newhouse PA, Grafman JH: Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc 37: 725–729, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canning SJ, Leach L, Stuss D, Ngo L, Black SE: Diagnostic utility of abbreviated fluency measures in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Neurology 62: 556–562, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters LL, Boter H, Buskens E, Slaets JP: Measurement properties of the Groningen frailty indicator in home-dwelling and institutionalized elderly people. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13: 546–551, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, Fonck M, Soubeyran PL: Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol 23: 2166–2172, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, van Gemert EA, de Haan RJ, Schuurmans MJ, de Rooij SE: Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized older patients with distinct risk profiles for functional decline: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 7: e29621, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oud FM, de Rooij SE, Schuurman T, Duijvelaar KM, van Munster BC: [Predictive value of the VMS theme ‘Frail elderly’: Delirium, falling and mortality in elderly hospital patients]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 159: A8491, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, Dalton C, MacKay K, Pellegrino B, Anantharaman P, Schmidt R: Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1379–1384, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mauri JM, Vela E, Clèries M: Development of a predictive model for early death in diabetic patients entering hemodialysis: A population-based study. Acta Diabetol 45: 203–209, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thamer M, Kaufman JS, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Cotter DJ, Bang H: Predicting early death among elderly dialysis patients: Development and validation of a risk score to assist shared decision making for dialysis initiation. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 1024–1032, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ: Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 72–79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Munster BC, Drost D, Kalf A, Vogtlander NP: Discriminative value of frailty screening instruments in end-stage renal disease. Clin Kidney J 9: 606–610, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Kornak J, Grimes B, Chertow GM: Comparison of self-report-based and physical performance-based frailty definitions among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 600–607, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meulendijks FG, Hamaker ME, Boereboom FTJ, Kalf A, Vögtlander NPJ, van Munster BC: Groningen frailty indicator in older patients with end-stage renal disease. Ren Fail 37: 1419–1424, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Painter P, Kuskowski M: A closer look at frailty in ESRD: Getting the measure right. Hemodial Int 17: 41–49, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, Dignam J, Martin K, Petrylak DP, Stadler WM, Rodin M: A pilot study of the vulnerable elders survey-13 compared with the comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older patients with prostate cancer who receive androgen ablation. Cancer 109: 802–810, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owusu C, Koroukian SM, Schluchter M, Bakaki P, Berger NA: Screening older cancer patients for a comprehensive geriatric assessment: A comparison of three instruments. J Geriatr Oncol 2: 121–129, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.