In this issue of JAMA, Zapata and colleagues discuss framing the provision of unnecessary medical care as a patient safety problem and managing this problem using the hospital Patient Safety Committee (1). The case presented highlights the lack of clarity around who is accountable for addressing overuse issues. All hospitals are concerned with the safety of their patients, and the authors provide a thoughtful discussion of the merits and challenges of using the patient safety infrastructure to target overuse. To retain focus on important safety issues while facilitating greater attention to the problem of overuse requires defining the relationship between overuse and patient safety.

In 1990, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” (2) As part of the IOM National Roundtable on Health Care Quality, problems with health care quality were classified as underuse (failure to provide a service that would have benefitted a patient), misuse (selection of an appropriate service but lack of patient benefit due to a preventable complication), and overuse (use of a service for which the potential for harm exceeds the potential for benefit). (3)

Traditionally, efforts to improve quality have focused mainly on underuse (i.e., not doing enough) and misuse (i.e., preventable complications). In recent years, overuse (i.e., doing too much) has been a topic of increasing interest amid a growing emphasis on optimizing care value, in which ‘value’ reflects the balance between net clinical benefit and cost. With this attention to overuse and value has come a promulgation of related terms and concepts. The term “low value care” generally refers to health care services with little potential benefit or for which less expensive similar alternatives are available. (4) Low-value care includes overused services but it also includes services that yield excessive cost compared to other options with equivalent benefit. Further, several terms have been used to refer to different specific types of overuse; these include overtreatment (provision of treatments that are more likely to harm than benefit patients) and overtesting (use of tests that are more likely to result in patient harm than patient benefit) as well as the related concept of overdiagnosis (diagnostic labeling of conditions that are not clinically relevant).(5) These categories of overuse are interrelated; overtesting can lead to overdiagnosis, overtreatment, more overtesting, or all of these.

Despite recent attention to overuse there are a number of challenges to addressing it. First, a key challenge is that overuse is inconsistently tracked and seldom prioritized, largely because few performance measures addressing overuse have been developed and validated. (6) Second, overuse is underappreciated as a problem that affects outcomes that are important to patients and clinicians for several reasons. Clinicians may underestimate the prevalence of overuse because identifying overuse is complex – determining appropriateness of an intervention is often clinically nuanced and may require knowledge of individual patient preferences. Third, harms from overuse often occur after a long cascade of interventions and may be difficult to recognize in connection with the upstream unnecessary service. Because clinical harms related to overuse are not appreciated, many clinicians view overuse as a cost issue and conflate efforts to reduce overuse with rationing. Fourth, as noted in the article by Zapata and colleagues, problems of overuse often have no clear administrative “home.” Rather, efforts to reduce overuse rely on a few motivated individuals working against a culture of care that tends to value doing more. For all of these reasons there may be little collective institutional energy for reducing overuse.

Overuse that results in clinical harm is a patient safety problem that should not be ignored by the safety community.(7,8) Safety, defined as “freedom from accidental injury”, was included among IOM’s six key dimensions of a high-quality healthcare system (9) and some safety issues are tracked almost universally by physician groups, hospitals, and health systems. (10) For example, a patient who undergoes an unnecessary contrast CT scan that is complicated by acute kidney injury and prolonged hospitalization has experienced clinical harm related to overuse and a compromise in safety. In this case overuse is definitely a patient safety issue. The harm can also occur downstream from an overused test. For example, if an unnecessary chest radiograph reveals a non-specific abnormality for which a CT is subsequently performed, a complication from that CT scan also represents a clinical harm related to overuse, although it might not be recognized as such.

Framing overuse through the lens of patient safety highlights overuse as an issue that affects clinical outcomes that are most important to patients and clinicians. The active inclusion of harms from overuse under the auspices of an institution’s patient safety infrastructure addresses some of the challenges to reducing overuse and has a number of practical benefits. First, this approach can help motivate and engage clinicians in overuse reduction efforts by drawing attention to the potential harms to patients from overuse and demonstrating that overuse is not simply a financial problem. Second, this approach can broaden the lens for quality improvement activities. Its inclusion reinforces the notion that in system redesign efforts, different aspects of quality must be considered in tandem to achieve desired results. (8,11,12) Third, this model gives overuse issues an administrative “home” within an institution rather than relying on a few individuals with interest in the area to bring important issues to general attention.

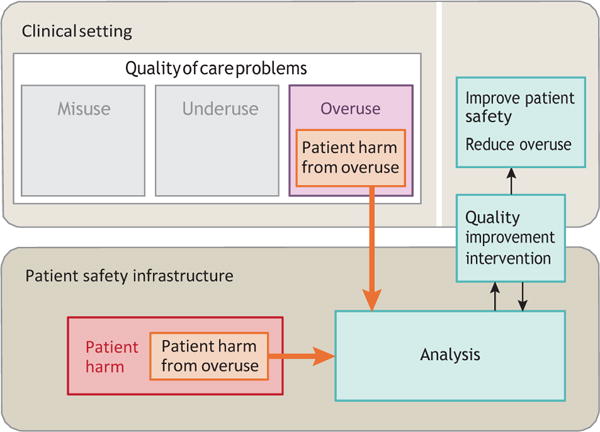

How might a formal integration of overuse harms into patient safety activities be implemented at the institution level (Figure 1)? Patient safety officers and committee members can work to standardize measurement of priority issues and track performance over time. When evaluating patient safety lapses committees can routinely assess the appropriateness of services that culminated in patient harm to help identify and address overuse. Analysis of safety lapses could incorporate evaluation of whether the intended service or those services leading up to the safety lapse were actually necessary, which may unmask harms attributable to overuse. Committees can also specifically seek out cases of harm from services known to represent overuse and encourage clinicians to bring such cases to their attention. Assessment and analysis activities can then be used to inform quality improvement efforts that seek to reduce patient harm while maximizing other important outcomes. These efforts could also benefit the community at large by leading to the development of much needed quality measures related to overuse. (6)

Figure 1.

Identification and Management of Overuse as a Patient Safety Problem

Patient harm from overuse can be identified in 2 ways. First, overused services delivered in the clinical setting that cause patient harm can be identified and addressed through the patient safety infrastructure. Second, overuse can be actively unmasked in cases of patient harm. Analyses of patient harm from overuse can lead to quality improvement interventions to reduce overuse and improve patient safety.

While this model has benefits, a taxonomy maintaining distinctions between safety and overuse is also useful to ensure that important issues are not overlooked. Many harms from overuse do not threaten patient safety in the traditional sense. For example, in the case presented by Zapata and colleagues, the patient had unnecessary laboratory testing and an unneeded radiograph, perhaps causing discomfort, some radiation exposure, and several unnecessary consultations; these may have been inconvenient for the patient and also may have distracted consultants from patients with more pressing clinical needs. In addition, there was financial harm to the health care system and perhaps to the patient associated with all of these unnecessary services. Broadening the scope of patient safety to include financial harms, subtle patient harms such as inconvenience or mild temporary discomfort, or harms to the health care system or other patients could dilute the important goals of the patient safety movement. This broader lens also could distract patient safety committees from evaluation of other lapses in safety that have more serious clinical implications, and could trivialize the often very real harms of overuse. While these types of harms from overuse are important to acknowledge and address to achieve related but distinct national goals around value, cost, and care quality, they should not be conflated with clinically important patient injury.

In the case presented by Zapata and colleagues, the patient safety committee ultimately reviewed the case and recommended a number of interventions to counteract overuse in the future. This outcome was positive but should not imply that all overuse should be viewed as a threat to patient safety. While overuse by definition has the potential for patient harm, in a practical sense, integrating overuse into the patient safety infrastructure only when overuse causes serious direct patient harm can reinforce its importance while retaining the integrity of the critical mission to protect patients. Regardless of which individual stakeholders and committees in the health care organization are responsible for monitoring and addressing, commitment from institutional leadership and adequate resources must be allocated to elevate the problem and address its complexity in a meaningful way. The patient safety infrastructure provides a mechanism for bringing overuse to broader attention and reducing its most harmful examples.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Korenstein’s and Dr. Lipitz-Snyderman’s work on this paper was supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (award number P30 CA008748).

References

- 1.Zapata and colleagues, JAMA

- 2.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Division of Health Care Services. Lohr KN, Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee to Design a Strategy for Quality Review and Assurance in Medicare., United States . Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1990. Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998;280(11):1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schpero WL. Limiting low-value care by “choosing wisely”. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(2):131–134. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.02.pfor2-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, et al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world [published online Januray 6, 2017] Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries EF, Struijs JN, Heijink R, Hendrikx RJ, Baan CA. Are low-value care measures up to the task? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):405. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1656-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Are bad outcomes from questionable clinical decisions preventable medical errors? A case of cascade iatrogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(5 Part 1):327–333. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_1-200209030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384–2390. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson WC, Berwick D, Bisgard J. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty-First Century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare.gov Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed 30 January 2017.

- 11.Emanuel L, Berwick D, Conway J, et al. Advances in Patient Safety. What Exactly Is Patient Safety? In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Vol. 1. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Assessment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf SH. Patient safety is not enough: targeting quality improvements to optimize the health of the population. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(1):33–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]