Abstract

Background

Prior work suggests blood pressure in African Americans (AAs) is more sensitive to the effects of aldosterone than in Caucasians. This mechanism may relate to a negative response of the vascular endothelium to aldosterone, including reduced glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity.

Methods

Thirty-three African Americans (eleven hypertensives, twenty-two controls) without evidence of diabetes or metabolic syndrome completed protocol. The protocol included measurement of in vivo microvascular endothelial function by digital pulse arterial tonometry and ex vivo measurement of endothelial function by videomicroscopy of arterioles obtained from these same subjects with and without exposure to aldosterone or spironolactone. Systemic and arteriolar G6PD activities were also measured.

Results

In vivo and ex vivo microvascular endothelial function were impaired in AAs with hypertension. One-hour exposure with aldosterone impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in arterioles from normotensive subjects while 1 hour of spironolactone exposure reversed endothelial dysfunction in arterioles from hypertensive subjects. G6PD activity was impaired in hypertensive arterioles.

Conclusions

Aldosterone-related endothelial dysfunction may be responsible for at least a portion of the greater blood pressure sensitivity to aldosterone in AAs. This may be in part related to vascular suppression of G6PD activity.

Keywords: Aldosterone, African American, Hypertension, Endothelial Function, Microvasculature

Introduction

Approximately sixty-five million American’s are hypertensive and African Americans (AAs) suffer disproportionately from the cardiovascular complications of this disease, which include coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, and renal failure.1–4 Hypertension also occurs earlier in life and with greater severity in AAs.5,6 While the biological underpinnings of this difference remain elusive, growing evidence suggest increased sensitivity to circulating aldosterone importantly contributes to an increased incidence of hypertension and its complications in AAs.7–9 High normal plasma aldosterone levels in humans are associated with increased risks of developing hypertension.14–16

Individuals exposed to excessive systemic aldosterone have endothelial dysfunction,10–12 and heightened aldosterone sensitivity in African Americans (AAs) may drive the development of hypertension through endothelial damage.13 Multiple studies have evaluated endothelial function in AAs with and without hypertension.14–19 The majority of the studies demonstrate impaired endothelial function in normotensive AAs and hypertensive AAs. Aldosterone may induce endothelial dysfunction through increased oxidative stress through multiple pathways, including suppression of G6PD activity.20 Currently, there are limited data as to the direct impact of aldosterone at a high normal physiological level on vascular endothelial function in AAs. There is also scant evidence regarding G6PD activity of human resistance arterioles in African Americans with hypertension relative to normotensive individuals. Further, while chronic mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism improves endothelial function in the conduit vessels of patients with primary hyperaldosteronism,11 little is known as to the direct impact of acute antagonism on endothelial function of the resistance vessels primarily responsible for controlling blood pressure. In this study, we explore these unanswered questions with both in vivo and ex vivo studies of vascular endothelial function in AA volunteers.

Methods

Subjects

The Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin approved the study protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study procedures. African Americans, as defined by having at least one grandparent of African American heritage, were eligible for enrollment. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg based on 3 averaged measurements at the time of screening or current anti-hypertensive treatment. Potential participants with a history of stroke, peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, active malignancy, poorly controlled hypertension at the time of screening (systolic blood pressure ≥170 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg), and prevalent illicit drug or alcohol abuse were excluded from participation. Individuals who met criteria metabolic syndrome were also excluded to eliminate confounding of the vascular studies results by prevalent metabolic syndrome. Individuals were considered to be eligible for the control group if their blood pressure was < 140/90 mmHg and had no history of anti-hypertensive medication use.

Study Protocol

Study procedures were performed in the Adult Translational Research Unit at the Medical College of Wisconsin from 7AM to 10AM. Hypertensive subjects were instructed to hold anti-hypertensive medications for one week prior to the study visit. All subjects were asked to hold any vasoactive medications 24 hours prior to the study. Subjects fasted overnight (12 hours) prior to the study visit. A medical history as well as subject weight, height, and waist circumference were measured and recorded. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured in triplicate and averaged. Subjects laid supine in a quiet, dimmed, temperature controlled (22–24°C) room for approximately 60 minutes prior to blood samples. After 60 minutes of rest, blood samples were obtained for measurement of G6PD activity, systemic markers of oxidative stress, renin activity, and aldosterone level. Participants then were instructed to stand for 20 minutes, and blood was drawn to measure plasma aldosterone level and renin activity following the 20 minute period. They were then asked to lay supine for 10 minutes after which digital pulse arterial tonometry (DPAT) was measured.

Measurement of Endothelial Function

Digital Peripheral Arterial Tonometry (DPAT)

DPAT represents a measurement of primarily microvascular endothelial function that is in part NO dependent.21 Measurements were performed simultaneously with FMD measurements using EndoPAT 2000 (Itamar Medical Ltd, Caesarea, Israel). This involves the placement of fingertip-mounted probes to the participant’s index fingers that act as pneumonic cuffs allowing for measurements of digital pulse volume. The probes contain an inflatable air cushion and allow for pressure changes to be transmitted and digitalized. Cuff inflation pressure was electronically set at 70 mmHg or 10 mmHg below diastolic pressure. Baseline measurements in both index fingers were obtained for 2 minutes and 20 seconds prior to forearm cuff inflation. DPAT measurements were measured and reported in an automated fashion. DPAT is calculated as the ratio of the post-deflation pulse amplitude to the baseline pulse amplitude ratio in the arm experiencing hyperemia compared to the same ratio in the opposite (control) arm for the 90–150 second period post-cuff occlusion. In test-retest studies performed on 16 subjects on two separate days without an intervention, our laboratory intra-class correlation coefficient for DPAT measurements is 0.75.

Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilation of Arterioles by Videomicroscopy

Human subcutaneous arterioles were obtained by gluteal adipose pad biopsy in a subgroup of subjects as previously described.21–23 Briefly, local anesthesia (1% lidocaine) injected into the skin over the gluteal area using sterile technique. Approximately 1–1.5 cm vertical incision was made in the upper lateral gluteal quadrant on the patient’s non-dominant side to expose the gluteal subcutaneous adipose tissue. Approximately 2–2.5 cm3 of subcutaneous adipose was removed from adipose depot overlaying the superior margin of the gluteus maximus muscle. The incision was subsequently closed using absorbable suture followed by steristrips. The adipose tissue sample was transferred immediately into cold HEPES buffer (4°C) and immediately analyzed.

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation of arterioles dissected from the adipose samples was measured as previously described.21–23 Briefly, vessels were suspended in a micro-organ chamber, with the lumen cannulated on each end by a glass pipet and maintained in warm Krebs buffer at 37°C in 21% oxygen. Vasodilation is the percentage change from baseline diameter measured following exposure to endothelin-1 pre-constriction (to 50% −70% of pre-constriction diameter). The endothelial-dependent percent vasodilation was evaluated at each dose of acetylcholine from 10−10 to 10−5 M. Our prior work shows endothelial-dependent vasodilation from these gluteal vessels to acetylcholine (Ach, Sigma, St. Louis) is approximately 95% endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) synthase dependent.21, 22 Smooth muscle reactivity was determine at the end of each acetylcholine dose-response experiment using papaverine (0.2 mM) (Pap, 2 × 10−4 mol/L, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The studies were then repeated for all vessels after pretreatment for an hour with either spironolactone (10 µM) or aldosterone (20 ng/dL), a concentration known to be at the upper limit of the normal range.22

Quantification of Arteriolar G6PD Activity

Arteriolar G6PD activity was measured from vessels of a sub-group of subjects who underwent gluteal adipose pad biopsy. The method for measuring G6PD activity from tissue samples was adapted for vessel from prior cell culture work.23 Homogenated microvessels were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (0.9%) and centrifuged at 2000 × g at 4 C° for 10 minutes. Centrifuges samples were divided between two cuvettes containing buffer (50 mM Tris, 1mM MgCl2, pH 8.1). Enzyme activity was determined using a plate-reader spectrophotometer by measuring the rate of increase of absorbance at 340 nm from the conversion of NADP+ to NADPH by either G6PD or 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6-PGD). The rate of change in activity was measured over a five minute period. In one cuvette, substrate for both G6PD and 6-PDG were added [glucose-6-phosphate (50µM), 6-phosphogluconate (30 µM), and NADP+ (800 µM)]. To the second cuvette, only substrates for 6-PDG were added [6-phosphogluconate (30 µM), and NADP+ (800 µM)]. Subtracting the activity of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase from the total dehydrogenase activity provided arteriolar G6PD activity. G6PD activity measurements were normalized to the protein level. Samples with < 0.1 µg of protein were excluded from the analysis. Results are reported as nmol/ min/mg protein.

Quantification of Superoxide Production

In a small subset of vessels (N=3 hypertensives, N=2 normotensives), vascular superoxide production was measured using the chemiluminescence day L-012.24 Vessels were incubated with or without 10 µM of spironolactone in HBSS buffer at room temperature for 1 hour. Vessels were then transferred to 96-well plates containing 200 µl HBSS, 10 µM NADH, and 400 µM L-012 (Wako, VA, USA). Vessels were pre-incubated in dark at 37 C for 10 min and kinetic reads taken every 60 seconds over a 10 minute interval (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices). Background luminescence was subtracted, and measurements were normalized to the protein level and reported as RLU/min/µg protein. Results were log transformed to assure a normal distribution of the data

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using R 2.13, SigmaStat 12.0 and SPSS 21.0. DPAT and arteriolar G6PD activity were natural log and log transformed, respectively, to assure normal data distribution of these variables. The study was powered with DAPT as a primary outcome. Assuming a difference in mean of 0.53 and σ=0.50, 22 normotensive and 11 hypertensive subjects give 80% to see a difference between groups at α=0.05. To account for missing data in plasma renin, plasma aldosterone, and systematic G6PD activity we assumed that our data were missing at random and developed imputation models for these missing components. Multiple imputations (100 imputations for each outcome) were performed. Statistical analyses with these variables were applied separately for each of the imputed datasets and the results were aggregated using the methodology proposed by Little and Rubin (R. Little and D. Rubin, Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2nd ed., Wiley, 2002) and implemented in the R package “norm” (www.r-project.org). Participant baseline characteristics, in vivo measures of endothelial function and vascular stiffness, G6PD activity, standing plasma aldosterone, and both supine and standing plasma aldosterone to renin activity ratio were expressed as mean± SE and compared using unpaired-t-test or chi-square test as appropriate. Ach dose-response curves comparing normotensive subjects and hypertensive, comparing vessels expose to spironolactone to those not exposed to spironolactone, and comparing vessels exposed to aldosterone to those unexposed were analyzed by separate two-way mixed analyses of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc analyses at each Ach dose was performed if P<0.05 to evaluated for interaction and the overall difference between the dose and percent vasodilation. Age adjustments for measurements of endothelial function (DPAT and percent vasodilation to 10−5 M Ach) were performed using generalized linear models. Correlations between measurements of G6PD activity, plasma aldosterone, plasma renin, and measures of endothelial function and vascular stiffness were analyzed for significance using Pearson’s r or Spearman’s ρ as appropriate. In vitro measurements of arteriolar vasodilation, G6PD activity, and superoxide production were not computed using multiple imputations given these data were obtained from a subset of participant’s by study design. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject Demographics

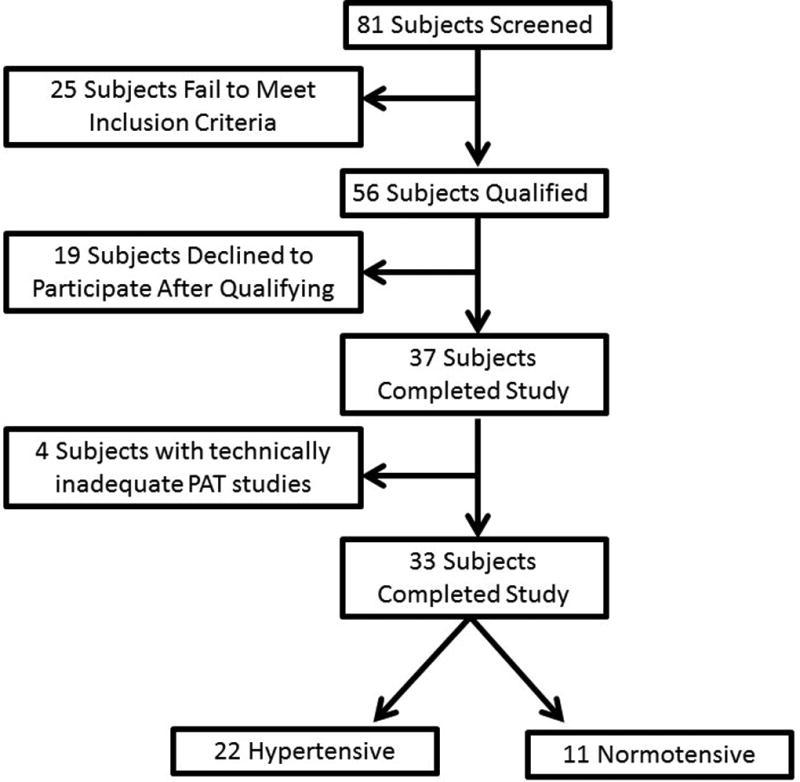

A total of 81 subjects were screened for the study. Twenty-five subjects failed to meet inclusion criteria following screening. 19 individuals who met criteria for enrollment declined participation following screening, resulting in thirty-seven subjects who underwent in vivo vascular studies. 24 subjects elected to undergo adipose tissue biopsy available for vasoreactivity experiments. Four subjects had technically inadequate in vivo studies, leaving 33 subjects (11 hypertensive subjects, 22 normotensive controls) for analyses of in vivo data. The baseline characteristics of these 33 subjects are shown in Tables 1 and 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to their sex, heart rate, liver function tests, lipid profile, body mass index, and fasting glucose. Hypertensive subjects were borderline significantly older than normotensive subjects by an average of 7.5 years (hypertensive 48.4±8.9, normotensive 40.9±9.7, P=0.05). Both diastolic blood pressure (hypertensive 85±27, normotensive 72± 12, P=0.01), and systolic blood pressure (hypertensive 145±17, normotensive 118 ± 14, P<0.001, respectively) were higher in hypertensive patients. There were no significant differences between supine or standing measures of systemic aldosterone and renin levels. No subjects were on chronic mineralocorticoid inhibitor therapy. Three of the 11 hypertensive subjects were on either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Two subjects were on b-blockade (one atenolol, one metoprolol), and one on hydralazine.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics

| Hypertensive (N=11) | Normotensive (N=22) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean | Mean | P-value | |

|

| |||

| Age | 48±9 | 41± 10 | 0.05 |

|

|

|||

| Sex (% female) | 54.5%(6) | 40.9%(9) | 0.16 |

|

|

|||

| Current Smoker | 45.5%(5) | 22.7%(5) | 0.37 |

|

|

|||

| Family history of Early CAD | 25.0%(3) | 20.8%(5) | 0.78 |

|

|

|||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.6 ± 6.6 | 27.5 ± 5.9 | 0.20 |

|

|

|||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 73± 15 | 76 ± 16 | 0.68 |

|

|

|||

| AST (U/L) | 21 ± 5 | 23 ± 13 | 0.64 |

|

|

|||

| ALT(U/L) | 18 ± 8 | 19 ± 13 | 0.78 |

|

|

|||

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 61± 26 | 55± 13 | 0.38 |

|

|

|||

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 113 ± 34 | 94 ± 29 | 0.11 |

|

|

|||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 82± 30 | 97± 74 | 0.56 |

|

|

|||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190 ± 38 | 168± 27 | 0.07 |

|

|

|||

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 145 ± 17 | 118± 14 | <0.001 |

|

|

|||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 85 ± 27 | 72 ± 12 | 0.01 |

|

|

|||

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 63 ± 9 | 64± 11 | 0.82 |

All data presented as mean±SD

Table 2.

Systemic Renin Concentration, Aldosterone Concentration, and G6PD Activity

| Hypertensive | Normotensive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | |||

| Serum G6PD Activity | 219± 21 | 245 ± 16 | 0.33 |

| Supine renin level (ng/mL/hr) | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 0.68 |

| Standing renin level (ng/mL/hr) | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.84 |

| Supine aldosterone level (ng/dL) | 6.72 ± 1.10 | 6.81 ± 0.83 | 0.94 |

| Standing aldosterone level (ng/dL) | 4.41 ± 0.91 | 4.61 ± 0.67 | 0.86 |

| Supine aldosterone to renin ratio | 35.0 ± 9.3 | 43.9 ± 27.1 | 0.75 |

| Standing aldosterone to renin ratio | 74.7 ± 51.4 | 92.4 ± 36.5 | 0.79 |

All data presented as mean±SE

In Vivo Measurement of Endothelial Function

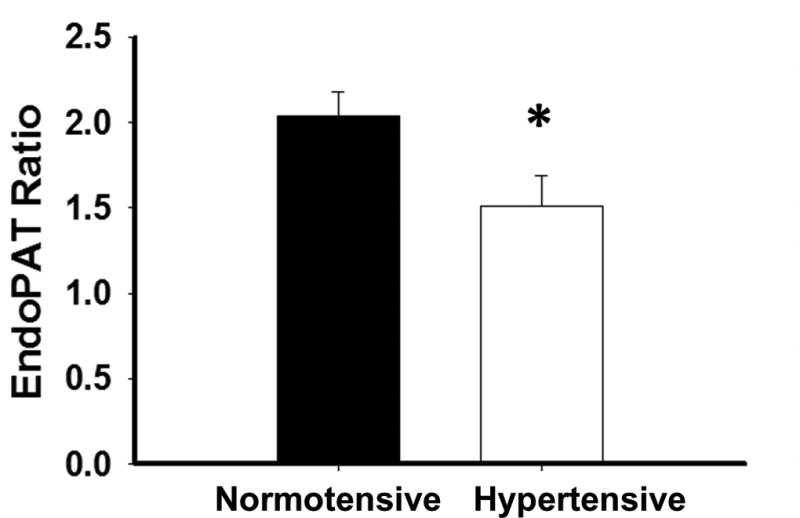

DPAT ratio was significantly lower in the hypertensive subjects compared to normotensive (1.51±0.56 vs. 2.03±0.62, P=0.03) (Figure 2). This difference remained significant following age adjustment (P=0.014).

Figure 2.

Endothelial function by digital pulse arterial tonometry is impaired in AAs with hypertension. *-P=0.03 (N=33 total, N=22 normotensive, N=11 Hypertensive)

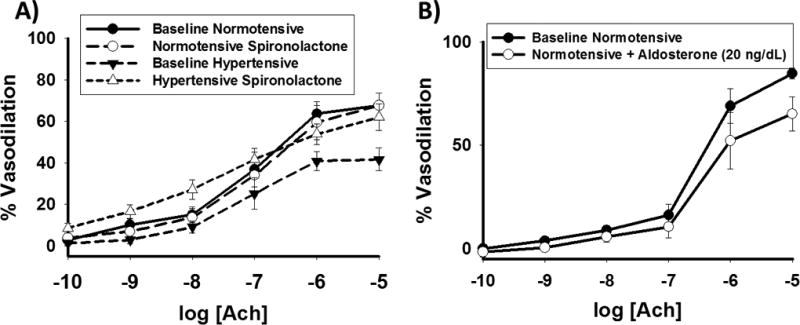

Impact of Aldosterone and Spironolactone Exposure on Microvascular Endothelial Function in Arterioles from Subjects with and without Hypertension

Normotensive and hypertensive groups did not differ with respect to vasodilation with 0.2mM concentration of papaverine [normotensive 94.9% (N=9) vs hypertensive 98.1% (N=6), P=0.40]. There were no significant differences in baseline arteriolar diameter between hypertensive subjects and normotensive controls (80.5±25 vs. 78.8±42 µm, P=0.92). Endothelium-dependent vasodilation to maximum dose Ach (10−5 M) was significantly decreased in those with hypertension compared to normotensive groups [41.9 ± 16.0% (N=6) vs. 65.9 ± 18.8% (N=9) P=0.02]. This difference remained significant follow age adjustment (P=0.02). Comparing dose-response curves to Ach, 1 hour of exposure to spironolactone reversed arteriolar endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive AA arterioles (P=0.01, Figure 3a). Vasodilation to the peak dose of Ach (10−5 M) was lower in hypertensive subjects compared to normotensive subjects (41.9±16.0 vs. 65.9±18.8%, P=0.02, P=0.01 following age-adjustment). Spironolactone exposure had no impact on vasodilation in vessels from normotensive subjects (P=0.77, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(A) 1 hour of spironolactone exposure (10 µM) reverses arteriolar endothelial dysfunction in AAs with hypertension (P=0.01 overall, *-P<0.04 at the indicated doses of acetylcholine, N=7 hypertensive, N=8 normotensive) (B) 1 hour of aldosterone exposure (20 ng/mL) impairs endothelial function in arterioles from normotensive AAs (P=0.02 overall, *-P<0.05 at the indicated doses of acetylcholine, N=5). Ach- acetylcholine in molar concentrations.

In addition, we tested Ach mediated vasodilation of arterioles from 5 additional normotensive individuals with and without 1 hour or pre-incubation with aldosterone. Normotensive AAs showed decrease vasodilator response to all doses of Ach following exposure to aldosterone (P=0.02, Figure 3b).

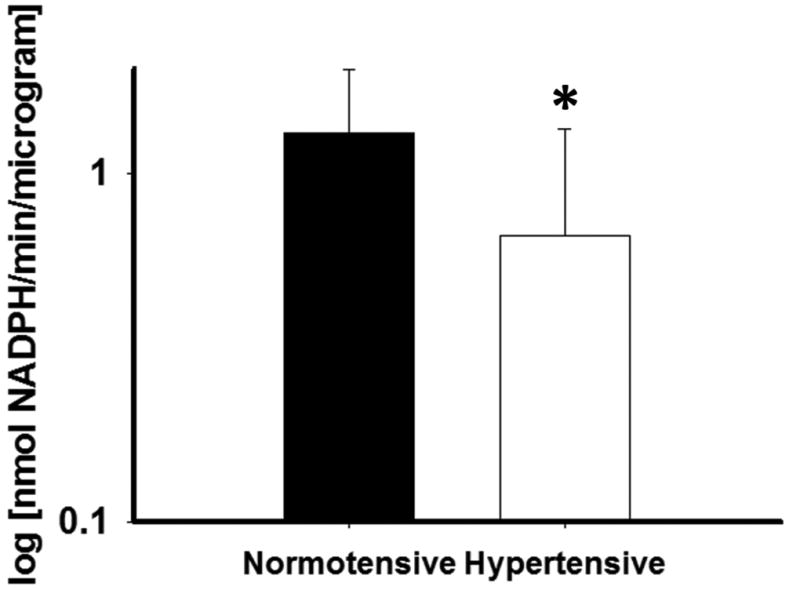

Arteriolar G6PD Activity and Superoxide Production

G6PD activity level in arterioles (log transformed) measured from a sub-group of subjects who underwent gluteal adipose pad biopsy was significantly lower for the hypertensive subjects compared to normotensive controls, [0.66 ± 0.68 (N=8) vs 1.33 ± 0.68 log (nmol NADPH/min/microgram) (N=16), P=0.03, Figure 4]. Spironolactone exposure significantly reduced superoxide production as measured by L-012 fluorescence [3.13±0.37 vs. 2.73±0.24 log (RLU/min/µg protein), P=0.03]

Figure 4.

G6PD activity is impaired in arterioles for AAs with hypertension relative to normotensive AA controls. (N=16 normotensive, N=8 hypertensive, *-P=0.03).

Aldosterone Levels and Associations with G6PD Activity and Microvascular Function

For 10 of the 15 subjects [6 hypertensive (none on medical therapy), 4 normotensive] with arteriolar vasodilatory measurements, matching supine and standing aldosterone levels were available for comparison. Vasodilation to peak dose Ach did not correlate with supine or standing aldosterone levels, (r=−0.21, P=0.50; r=−0.19, P=0.54). DPAT did not correlate with either supine or standing aldosterone levels (r=0.18, P=0.34 and r=0.17, P=0.38). G6PD activity level did not correlate with either DPAT (r=0.16, P=0.44) or vasodilation to peak dose Ach (r=0.39, P=0.20).

Discussion

Several recent studies suggest increased blood pressure sensitivity to aldosterone along with a closer association between aldosterone and hypertension in AAs.8, 9 Our study extends these findings by suggesting aldosterone may act to increase blood pressure by inducing endothelial dysfunction in human resistance vessels at physiological concentrations. In vivo and in vitro measures of microvascular endothelial function confirm impaired microvascular function in hypertensive AAs compared to normotensive AAs. Short term (1 hour) aldosterone exposure at a physiological concentration impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation in subcutaneous gluteal arterioles of normotensive AA. Conversely, short-term mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism with spironolactone reverses endothelial dysfunction in arterioles from hypertensive AAs and reduces vascular oxidative stress. Finally, arteriolar G6PD activity is lower in hypertensive AAs compared to normotensive AA individuals, and spironolactone reduces superoxide production in human arterioles. Therefore, we demonstrate that impaired endothelial function could be a biologically plausible mechanism responsible for the positive correlation of aldosterone with blood pressure in AAs seen in prior work.8, 9

The physiological connection between hypertension and endothelial dysfunction is well established.25 Current data suggest a complex interplay between both entities leading to both pathological phenotypes.13 AAs may have an increased susceptibility to endothelial dysfunction with more severe dysfunction in the face of equivalent hypertension,14, 19 perhaps related to intrinsically lower NO bioavailability in part due to excessive oxidative stress from multiple sources including NADPH Oxidase.26 We further these findings by demonstrating that impairment of endothelial function in resistance arterioles from AAs may in part be due to increased sensitivity to physiological levels of aldosterone, and oxidative stress may be related to reduced G6PD activity. Our data also importantly translate prior work linking reduced G6PD activity to aldosterone exposure and endothelial dysfunction in cell culture and animals to human physiology.20, 23 The lack of a difference in systemic G6PD activity between groups despite differences in at the vascular level may reflect tissue-specific differences in regulation of G6PD abundance and activity.

Our data also show that mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition with spironolactone acutely reverses resistance vessel endothelial dysfunction in resistance arterioles from AAs with hypertension. We extend the growing body of literature describing the anti-hypertensive effects of mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition in AAs by supporting the concept that the effect may be in part secondary to inhibition of endothelium-based resistance vessel mineralocorticoid receptors.8, 9, 27, 28 Given the rapidity of the improvement to exposure, the ameliorative effect of mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition on endothelial function in this study is most likely generated via inhibition of the non-genomic, pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative stress effects of mineralocorticoid receptor activity.29 Similarly, aldosterone’s acute effects on human resistance arterioles are likely through non-genomic effects and could be via a combination of both mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent and independent responses.12, 30, 31 Mineralocorticoid receptor activation could be enhanced in the hypertensive population by oxidative-stress related inhibition of 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (11 β-HSDH2).32 Additionally, our data suggest that despite the wide-ranging systemic effects of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid inhibition on organs such as heart and kidney, the effects of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptor inhibitor on the vasculature in part mediate the overall anti-hypertensive effects of these exposures.

Our study has several limitations. We did not find correlations between systemic measurements of aldosterone and measurements of resistance vessel endothelial function. This may reflect a combination of a relatively small study population and/or differences between systemic and local vascular tissue concentrations of aldosterone that were not investigated in this study. We also only enrolled African American subjects in this study. As such, we cannot specifically comment on differences in microvascular responses to aldosterone and spironolactone between AAs and non AAs with our data. Antihypertensive medications were held only for one week prior to the study, and other vasoactive medications were held for only 24 hours prior to the study. While prior studies have not shown a significant impact of holding these medications acutely on endothelial function,33 we recognize that antihypertensive medications may not fully have been washed out by the date of study for each subject. We did not control subject sodium intake in this study that could influence our findings. However, given that free-living individuals in the US take in over twice the daily recommended dietary sodium, this is unlikely to be confounding the study results.34 Lastly, the subjects included in the study were not genotyped for G6PD, nor were subjects asked to if they have a family history of G6PD deficiency and therefore we cannot strictly rule out these factors as possible confounders. Balanced against these limitations are the novel findings regarding the acute impact of physiological aldosterone exposure and mineralocorticoid inhibition on human arterioles in AAs bolstering the concept that mineralocorticoid inhibition may have a biological foundation for superior efficacy in hypertension in AAs.

Conclusion

Resistance arterioles from AAs with hypertension exhibit endothelial dysfunction that appears in part related to sensitivity to aldosterone at physiological levels and mediated by mineralocorticoid receptor activation. This may account for reductions in G6PD activity in these resistance arterioles, contributing to vascular oxidative stress. Together with prior data, the current work suggests that the etiology of hypertension in AAs at least in part is related to sensitivity to aldosterone even at physiological levels. These data support further translational work to determine whether mineralocorticoid blockade may offer superior efficacy relative to current anti-hypertensive regimens recommended for AAs with hypertension.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study subject enrollment.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was funded by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Elsa Shoeneich Medical Research Fund. Dr Widlansky receives grant support from the NIH (K23HL089326 and HL081587), the Doris Duke Foundation, and Merck, Sharp, & Dohme Corp. Drs. Dharmashankar and Wang have been funded by T32HL007792.

Funding for a portion of this work was received from the NIH.

Footnotes

We have no conflicts of interest to report relevant to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: a rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142248.54761.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissela B, Schneider A, Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Miller R, Alwell K, et al. Stroke in a biracial population: the excess burden of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 2004;35:426–31. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110982.74967.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–13. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weir MR, Saunders E. Pharmacologic management of systemic hypertension in blacks. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:46H–52H. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weir MR. Salt intake and hypertensive renal injury in African-Americans. A therapeutic perspective. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:635–44. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00048-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Gharbawy AH, Nadig VS, Kotchen JM, Grim CE, Sagar KB, Kaldunski M, et al. Arterial pressure, left ventricular mass, and aldosterone in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:845–50. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.3.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu W, Eckert GJ, Hannon TS, Liu H, Pratt LM, Wagner MA, et al. Racial differences in sensitivity of blood pressure to aldosterone. Hypertension. 2014;63:1212–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grim CE, Cowley AW, Jr, Hamet P, Gaudet D, Kaldunski ML, Kotchen JM, et al. Hyperaldosteronism and hypertension: ethnic differences. Hypertension. 2005;45:766–72. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154364.00763.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G, Yin GS, Tang JY, Ma DJ, Ru J, Huang XH. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with primary aldosteronism: a biomarker of target organ damage. J Hum Hypertens. 2014 doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Green SA, Renfroe KY, Calhoun DA. Impaired endothelium-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation in hypertensive subjects with hyperaldosteronism. Circulation. 2004;109:2857–61. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129307.26791.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farquharson CA, Struthers AD. Aldosterone induces acute endothelial dysfunction in vivo in humans: evidence for an aldosterone-induced vasculopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:425–31. doi: 10.1042/cs1030425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dharmashankar K, Widlansky ME. Vascular endothelial function and hypertension: insights and directions. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:448–55. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duck MM, Hoffman RP. Impaired endothelial function in healthy African-American adolescents compared with Caucasians. J Pediatr. 2007;150:400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, Panza JA. Racial differences in nitric oxide-mediated vasodilator response to mental stress in the forearm circulation. Hypertension. 1998;31:1235–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassett DR, Jr, Duey WJ, Walker AJ, Howley ET, Bond V. Racial differences in maximal vasodilatory capacity of forearm resistance vessels in normotensive young adults. Am J Hypertens. 1992;5:781–6. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.11.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein CM, Lang CC, Nelson R, Brown M, Wood AJ. Vasodilation in black Americans: attenuated nitric oxide-mediated responses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62:436–43. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perregaux D, Chaudhuri A, Rao S, Airen A, Wilson M, Sung BH, et al. Brachial vascular reactivity in blacks. Hypertension. 2000;36:866–71. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn DF, Duffy SJ, Tomasian D, Holbrook M, Rescorl L, Russell J, et al. Effects of black race on forearm resistance vessel function. Hypertension. 2002;40:195–201. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000024571.69634.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leopold JA, Dam A, Maron BA, Scribner AW, Liao R, Handy DE, et al. Aldosterone impairs vascular reactivity by decreasing glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity. Nat Med. 2007;13:189–97. doi: 10.1038/nm1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nohria A, Gerhard-Herman M, Creager MA, Hurley S, Mitra D, Ganz P. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of digital pulse volume amplitude in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:545–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01285.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Rifai N, et al. Serum aldosterone and the incidence of hypertension in nonhypertensive persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:33–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leopold JA, Zhang YY, Scribner AW, Stanton RC, Loscalzo J. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase overexpression decreases endothelial cell oxidant stress and increases bioavailable nitric oxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:411–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000056744.26901.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishinaka Y, Aramaki Y, Yoshida H, Masuya H, Sugawara T, Ichimori Y. A new sensitive chemiluminescence probe, L-012, for measuring the production of superoxide anion by cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:554–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Epstein SE. Abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT, Malinski T. Race-specific differences in endothelial function: predisposition of African Americans to vascular diseases. Circulation. 2004;109:2511–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129087.81352.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flack JM, Oparil S, Pratt JH, Roniker B, Garthwaite S, Kleiman JH, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of eplerenone and losartan in hypertensive black and white patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1148–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA. Efficacy of low-dose spironolactone in subjects with resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:925–30. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sowers JR, Whaley-Connell A, Epstein M. Narrative review: the emerging clinical implications of the role of aldosterone in the metabolic syndrome and resistant hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:776–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dooley R, Harvey BJ, Thomas W. Non-genomic actions of aldosterone: from receptors and signals to membrane targets. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;350:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagata D, Takahashi M, Sawai K, Tagami T, Usui T, Shimatsu A, et al. Molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect of aldosterone on endothelial NO synthase activity. Hypertension. 2006;48:165–71. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000226054.53527.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garbrecht MR, Krozowski ZS, Snyder JM, Schmidt TJ. Reduction of glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding by the 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 inhibitor, Thiram. Steroids. 2006;71:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gokce N, Holbrook M, Hunter LM, Palmisano J, Vigalok E, Keaney JF, Jr, et al. Acute effects of vasoactive drug treatment on brachial artery reactivity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:761–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sodium:the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [AccessedNovember 24];2013 Feb; Available at: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/salt/pdfs/Sodium_Fact_Sheet.pdf. 14 A.D.