Abstract

Around the globe many people are suffering from oral pain and other problems of the mouth or teeth. This public health problem is growing rapidly in developing countries where oral health services are limited. Significant proportions of people are underserved; insufficient oral health care is either due to low availability and accessibility of oral health care or because oral health care is costly. In all countries, the poor and disadvantaged population groups are heavily affected by a high burden of oral disease compared to well-off people. Promotion of oral health and prevention of oral diseases must be provided through financially fair primary health care and public health intervention. Integrated approaches are the most cost-effective and realistic way to close the gap in oral health between rich and poor. The World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Health Programme will work with the newly established WHO Collaborating Centre, Kuwait University, to strengthen the development of appropriate models for primary oral health care.

Key Words: Global burden of oral disease, Inequity in oral health, Oral health care coverage, Oral health promotion, Integrated disease prevention, WHO collaborating centres

Introduction

Around the globe many people are suffering from oral pain and other problems of the mouth or teeth. This public health problem is growing rapidly in developing countries where oral health services are limited. Significant proportions of people are underserved; insufficient oral health care is either due to low availability and accessibility of oral health care or because oral health care is costly. In all countries, the poor and disadvantaged population groups are heavily affected by a high burden of oral disease compared to people who are well off. Promotion of oral health and prevention of oral diseases must be provided through financially fair primary health care and public health intervention. Integrated approaches are the most cost-effective and realistic way to close the gap in oral health between rich and poor. The World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Health Programme has developed policies and strategic directions for the improvement of oral health in the 21st century [1]. Four strategic directions provide the framework for focussing WHO's technical work for oral health: (1) reducing the burden of oral disease and disability, especially in poor and marginalized populations; (2) promoting healthy lifestyles and reducing risk factors to oral health that arise from environmental, economic, social and behavioural causes; (3) developing oral health systems that equitably improve oral health outcomes, respond to people's needs and legitimate demands and are financially fair, and (4) framing policies in oral health based on integration of oral health into national and community health programmes and promoting oral health as an effective dimension of developmental policy of society.

In 2007, the Oral Health Programme was given a unique mandate for strengthening the work for oral health by its two governing bodies, i.e. the Executive Board and the World Health Assembly (WHA). A comprehensive report on global oral health was prepared by the Secretariat (WHO Oral Health) for the governing bodies, and the WHA subsequently agreed on a resolution (WHA.60.17) which reads: ‘Oral health: action plan for promotion and integrated disease prevention’ [2,3]. This statement is a wide-ranging policy that gives direction to better oral health for people in the 193 member states. The WHO statement is an impetus for countries to develop or adjust national oral health programmes, and the policy is a strong support for the global actions that have been carried out by the WHO Oral Health Programme in recent years. The action plan for oral health promotion and integrated disease prevention encompasses several elements.

The Resolution Urges Member States to:

Adopt measures to ensure that oral health is incorporated into policies for the integrated prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases

Take measures to ensure that evidence-based approaches are used

Consider mechanisms to provide essential oral health care and incorporate oral health within the framework of primary health care

Consider the development and implementation of fluoridation programmes

Take steps to ensure that prevention of oral cancer is an integral part of national cancer control programmes

Ensure the prevention of oral disease associated with HIV/AIDS and the promotion of oral health and quality of life for people living with HIV

Develop and implement oral health promotion for school children as part of activities in health-promoting schools

Scale up capacity to produce oral health personnel

Develop and implement, in countries affected by noma, national programmes to control the disease within national programmes for the integrated management of childhood illness and reduction of malnutrition and poverty

Incorporate an oral health information system into health surveillance plans

Strengthen oral health research

Address human resources and workforce planning for oral health as part of every plan for health

Consider increasing the budgetary provisions that are dedicated to the prevention and control of oral and craniofacial diseases and conditions

The Resolution Requests the Director-General to:

Raise awareness of the global challenges in improving oral health, specifically, the needs of low-income countries and of poor and disadvantaged population groups

Ensure that WHO provides advice and technical support to member states for the development and implementation of oral health programmes

Promote continually international cooperation and interaction with and among all actors concerned with the implementation of the oral health action plan, including collaborating centres and non-governmental organizations

Communicate to UNICEF and other organizations of the United Nation system that undertake health-related activities

Policy Frameworks for Primary Health Care

The Ottawa Global Conference on Health Promotion in 1986 was the first of its kind focusing on healthy environments and lifestyles, and health systems oriented towards health promotion and disease prevention. In 2009, the 7th WHO Global Conference on Health Promotion took place in Nairobi, Kenya, and for the first time in history, oral health was addressed through a special session organized by the WHO Oral Health Programme [4]. According to the general concept of the conference, the discussions focused on community empowerment, oral health literacy and health behaviour, strengthening oral health systems, oral health through schools, partnerships and intersectoral action, and capacity building for primary health care and oral health promotion. The oral health inputs for the Nairobi call for action included:

A declaration that oral health is a human right and essential to general health and quality of life

Promotion of oral health and prevention of oral diseases must be provided through primary health care and general health promotion; integrated approaches are the most cost-effective and realistic way to close the gap in implementation of sound interventions for oral health around the globe

National and community capacity building for promoting oral health and integrated oral disease prevention requires policy and appropriate human and financial resources to reduce the gap between the poor and rich

Recently, WHO initiated a global analysis of social determinants of health and an important report from the WHO Commission on the social determinants of health was issued [5]. From the very beginning, the WHO Global Oral Health Programme contributed to the work carried out by the Commission by focusing on the social determinants of oral health. In a subsequent WHO publication [6], equity and implications for public health programmes have been outlined with the focus on priority problems in public health. The oral health chapter of this publication [7,8] suggests several entry points for public health action and development of primary oral health care is considered most important for countries tackling the persistent inequities in oral health.

Primary Health Care

The WHO Alma-Ata declaration of 1978 defined primary health care as [9]:

‘Essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination. It forms an integral part both of the country's health system, of which it is the central function and main focus, and of the overall social and economic development of the community. It is the first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system, bringing health care as close as possible to where people live and work, and constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process.’

The 2008 World Health Report was confined to revitalization of primary health care [10]. According to WHO, the service delivery reforms advocated by the primary health care movement aim to put people at the centre of health care to make services more effective, efficient and equitable. Health services that do this start from a close and direct relationship between individuals and communities and their caregivers. This, then, provides the basis for person-centeredness, continuity, comprehensiveness and integration, which constitute the distinctive features of primary care. Primary health care is commonly viewed as a first level of care or as the entry point to the health care system. It can also be taken to mean a particular approach to care concerned with continuing care, accessibility, community involvement and collaboration between sectors. Table 1 summarizes what the WHO sees as the differences between primary health care and care provided in conventional settings such as clinics or hospital outpatient departments or through disease control programmes that shape many health services in resource-limited settings.

Table 1.

Dimensions of care that distinguish conventional health care from people-centred primary health care [10]

| Conventional ambulatory medical care in clinics or outpatient departments | Disease control programmes | People-centred primary care |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on illness and cure | Focus on priority diseases | Focus on health needs |

| Relationship limited to the moment of consultation | Relationship limited to programme implementation | Enduring personal relationship |

| Episodic curative care | Programme-defined disease control interventions | Comprehensive, continuous and personcentred care |

| Responsibility limited to effective and safe advice to the patient at the moment of consultation | Responsibility for disease-control targets among the target population | Responsibility for the health of all in the community along the life cycle; responsibility for tackling determinants of ill-health |

| Users are consumers of the care they purchase | Population groups are targets of disease-control interventions | People are partners in managing their own health and that of their community |

Policy for Primary Health Care

The 2008 World Health Report on Primary Health Care [10] highlights the importance of four essential reforms: (1) coverage reforms that ensure that (oral) health systems contribute to equity in (oral) health and social justice and end exclusion, primarily by moving towards universal access and social health protection; (2) service delivery reforms that re-organize (oral) health services around people's needs and expectations to make them more socially relevant and responsive to the changing world while producing better oral health outcomes; (3) public policy reforms that secure healthier communities by integrating public health actions with primary care, pursuing healthy public policies across sectors and strengthening national and transnational public health interventions, and (4) leadership reforms that replace disproportionate reliance on command and control on the one hand and laissez-faire disengagement of the state on the other by inclusive, participatory, negotiation-based leadership.

Oral Health Care Globally

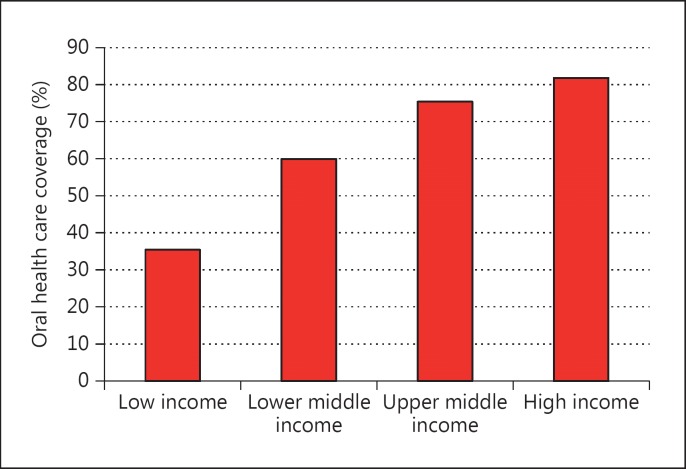

Many people around the globe suffer from oral pain or discomfort. It is a human right, however, that people be served by essential oral health care for ensuring quality of life. In numerous countries significant proportions of the population are not covered by such care; in particular, this is the case in low- and middle-income countries with a critical shortage of oral manpower. The availability of dentists across countries is shown in figure 1 [11]. Information about the number of dentists per 100,000 people is presented according to national income level. The availability of dentists is dramatically low for developing countries. In such case, primary health care workers specially trained in oral health and other ancillary staff may assist in early detection of illness or disease and provide essential care. The shortage of oral manpower is one important reason for the low coverage of oral health care observed in these countries. Less accessibility is another determining factor for people's use of oral health services. Oral health care is costly and imposes a heavy barrier on the use of services for many poor people. The global inequities in oral health care based on findings from the World Health Survey are illustrated in figure 2 [12]. Among adult people with an expressed need for oral health care, the mean oral health coverage varies substantially from the level of 40% in low-income countries to about 80% of people in high-income countries.

Fig. 1.

Mean number of dentists per 100,000 populations in countries, by national income level [11].

Fig. 2.

Mean oral health care coverage (%) in adults 18+ years of age with expressed need, by national income level [12].

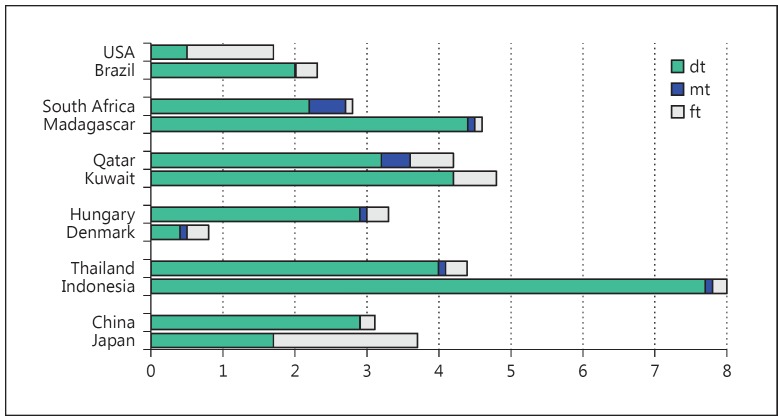

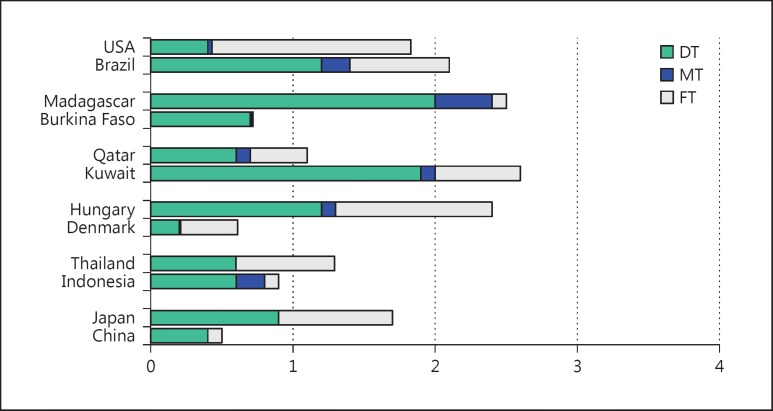

The unmet need for oral health care is well documented by country surveys carried out in all 6 WHO regions [13]. According to the WHO Global Oral Health Data Bank [14], in some countries the prevalence of dental caries among children may well remain moderate or low; however, the d/D component of the dental caries experience index is very high; such information for children aged 5-6 and 12 years for selected countries are given in figures 3 and 4. A parallel pattern of relatively high D component is observed among young adults of several countries (fig. 5). Universally, from low- to high-income countries, the poor and disadvantaged population groups have a high burden of oral disease and are underserved compared to well-off people. The lack of affordable oral health care because of direct payment or limited cost-sharing mechanisms frequently makes oral health a political issue. Within a country, variations in the individual's need for care and effective use of curative or preventive services are caused by structural factors like education, personal income, employment, accessibility of oral health services and existence of third-party payment systems [7]. Around the world there are also significant differences in oral health care coverage by age group; the political priority in oral health care is mostly given to children while older people are a highly neglected target group. A call for public health action for better oral health care of older people was expressed recently by WHO [15].

Fig. 3.

Mean number of primary teeth with experience of dental caries (dmft) among 5- to 6-year-olds of selected countries within WHO regions. dt = decayed teeth; mt = missing teeth due to caries; ft = filled teeth [14].

Fig. 4.

Mean number of permanent teeth with experience of dental caries (DMFT) among 12-year-olds of selected countries within WHO regions. DT = Decayed Teeth; MT = Missing Teeth; FT = Filled Teeth [14].

Fig. 5.

Mean number of permanent teeth with experience of dental caries (DMFT) among 35- to 44-year-olds of selected countries within WHO regions. DT = Decayed Teeth; MT = Missing Teeth; FT = Filled Teeth [14].

Primary Health Care for Oral Health

The WHA60.17 resolution is a political call for countries to strengthen their oral health systems by incorporating primary oral health care into national public health programmes. The development or adjustment of oral health systems in particular must consider the needs of the underserved poor and disadvantaged population groups and reach out to the community. Important activities for primary oral health care to address are the following:

Healthy and safe environments for oral health

Food supply and nutrition

Water and sanitation

Health-promoting schools

Age-friendly primary health care for oral health

Maternal and child oral health care

Health communication/oral health education

Disease prevention methods

Early detection

Pain control - emergency care for oral health

Provision of essential drugs

Treatment of common oral diseases and injuries

Comprehensive oral health care

Continuity of oral health care

Supportive referral systems

Priority to those people most in need

Primary Oral Health Care - An Important Area of Work for WHO Collaborating Centres

Currently, the WHO Oral Health Programme facilitates the development of primary health care models applicable to different community settings around the world. For further progress in this work, the Programme initiated the designation of the Kuwait University as a WHO Collaborating Centre (WHOCC) for Primary Oral Health Care. It is hoped that the designation of this new WHOCC will help optimal WHO assistance to countries for improved oral health care coverage and effective orientation of public health intervention towards health promotion and integrated disease prevention.

What is a WHOCC? Institutions are designated as WHOCC by the Director-General under a formal mechanism of collaboration to carry out activities in support of the Organization's programme at all levels. Overall, WHOCCs work on a diverse range of subjects across all WHO's technical programmes. Their activities include, for example, carrying out research for WHO, assisting in the development of WHO guidelines, gathering and analysing data for a WHO report, dissemination of information, providing a training course by request of WHO, standardization of terminology, or provision of technical advice to WHO.

WHOCCs have been designated since the establishment of WHO. As of 2012, WHO's network of WHOCCs brings together more than 800 highly regarded academic and scientific institutions in over 80 countries, supporting WHO technical programmes (e.g. the WHO Oral Health Programme) and priorities with time, expertise and funding. The designation is initially agreed for 4 years, and can be renewed before it ends. During the period of designation, the centre implements an agreed list of activities in support of WHO technical programmes independent of financial support given to the institution by WHO. The collaboration brings benefits to both parties. WHO gains access to top centres worldwide as well as the institutional capacity to support its global health work and ensure its scientific validity. Institutions benefit from enhanced visibility and recognition by national authorities, calling public attention to the health issues on which they work. The designation also opens up improved opportunities to exchange information and develop technical cooperation with other institutions, in particular at international level, and to mobilize additional resources from funding partners. Collaborating centres are encouraged to develop working relations with other centres and national institutions recognized by WHO by setting up or joining collaborative networks with the support of WHO.

Conclusions

The public health staff of Kuwait University has demonstrated considerable technical expertise in primary oral health care and as a WHOCC it is foreseen that the staff may further assist WHO in its ongoing work of creating appropriate primary health care models for oral health. The terms of reference and the 4-year work plan provide details of the activities planned for the years 2013 through 2017; WHO highly appreciates the engagement by the WHOCC staff for effective implementation of these activities and better oral health for all.

Disclosure Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE. Global policy for improvement of oral health in the 21st century - implications to oral health research of World Health Assembly 2007, World Health Organization. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health - World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 2008;58:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen PE, Kwan S. The 7th WHO Global Conference on Health Promotion - towards integration of oral health (Nairobi, Kenya 2009) Community Dent Health. 2010;27((suppl 1)):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blas E, Sivansankara Kurup A. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwan S, Petersen PE. Oral health: equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Sivansankara KA, editors. Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes. Geneva: WHO; 2010. pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen PE, Kwan S. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes - the case of oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization.1978: Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on PHC, Alma-Ata, 6-12 September. Available from http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf

- 10.World Health Organization . Primary health care: now more than ever. Geneva: WHO; 2008. The World Health Report 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. The World Health Report 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseinpoor AR, Itani L, Petersen PE. Socio-economic inequality in oral healthcare coverage. Results from the World Health Survey. J Dent Res. 2012;91:275–281. doi: 10.1177/0022034511432341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen PE. Oral health. In: Heggenhaugen K, Quah S, editors. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 677–685. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . WHO Global Oral Health Data Bank (2011). Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen PE, Kandelman D, Arpin S, Ogawa H. Global oral health of older people - call for public health action. Community Dent Health. 2010;27(suppl 2):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]