Abstract

Context:

The primary and definitive treatment of medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is surgical resection. Recurrent or residual disease is typically a result of incomplete surgical removal.

Objective:

Our objective is to develop a compound that assists in intraoperative visualization of cancer, which would have the potential to improve surgical cure rates and outcomes.

Results:

We report the biological characterization of Compound-17, which is labeled with IRdye800, allowing fluorescent visualization of MTC mouse models. We found that the agent has high affinity for two human MTC cell lines (TT and MZ-CRC1) in vitro and in vivo. We further tested the affinity of the compound in a newly developed MTC orthotopic xenograft model and found that Compound-17 produces fluorescent signals within MTC-derived orthotopic xenografts in comparison with a sequence-jumbled control compound and surrounding normal tissues.

Conclusions:

Compound-17 is a unique and effective molecule for MTC identification that may have therapeutic potential.

A mouse orthotopic medullary thyroid cancer model was developed and used to characterize a fluorescent-imaging agent, which may enhance intraoperative visualization and surgical resection.

Medullary thyroid cancers (MTCs) are derived from thyroid C-cells, named due to their calcitonin production, and account for 3% to 4% of thyroid cancers (1). For patients with MTC localized to the neck, complete surgical resection remains the best therapeutic option (2). These tumors are unresponsive to radioactive iodine therapy because they do not express the sodium–iodine symporter. External beam radiation is used for local control when surgery is no longer an option. Traditional chemotherapies are ineffective, and the Food and Drug Administration–approved multikinase inhibitors, vandetanib and cabozantinib, can result in high transient disease control rates but are not curative and are associated with toxicities (3, 4).

Achieving optimal surgical outcomes requires removal of all target tissue and minimizing surgery time and risk to other tissues. To accomplish this, imaging prior to surgery is imperative. Current imaging modalities have made impressive progress, but each has limitations. Ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography can be effectively used to identify primary tumors and used to determine gross lymph node involvement. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging using 18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine-PET and 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose-PET can identify between 35% and 45% of progressive MTC lesions (5). Nuclear medicine γ scintigraphy using 99mTc sestamibi can also be used but has poor sensitivity and lacks specificity due to uptake in a variety of tissues (6).

Complete removal depends on a surgeon’s ability to differentiate normal from diseased tissue. Intraoperative assessment is largely based on surgeon experience and pathological frozen sectioning analysis (FSA) of tissue that has been removed, typically lymph nodes and surgical margins. FSA is also time intensive as the surgeon waits for sample preparation, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and review by a pathologist (7). The other significant limitation of FSA is that it does not evaluate tissue left in situ. The extent of tissue removed is based on the discretion of the surgeon. This limitation of pathologic tissue identification during surgery points to a need for better intraoperative methods of assessment. Intraoperative imaging has been successfully adapted in other cancer types (8, 9). Fluorescence image–guided surgery using near-infrared (IR) fluorescent contrast agents has been shown to decrease residual tumor and improve survival in mouse models of melanoma and mammary adenocarcinomas (10). Similarly, proof of concept for using fluorescence-guided resection in papillary thyroid cancer was established in a transgenic BRAFV600E murine model (11). Tumor-specific imaging agents may improve patient outcomes if these agents can increase the accurate surgical removal of all malignant tissue (12).

An ideal molecule will be readily absorbed, nontoxic, available during the surgical procedure, and eliminated shortly after surgery. This molecule would need to be disease tissue specific with minimal uptake in normal tissues to reduce background activity (13). The molecule should be available intraoperatively to be seen easily by the surgeon. Near-IR agents enable visualization of fluorescence by the surgeon, which is not otherwise visible to the naked eye, and contribute relatively low auto-fluorescence. IRdye800 provides better tissue penetrance and brightness than most other near-IR agents while having a low toxicity profile (14), and thus was chosen as the label for our molecule.

A variety of near-IR fluorescent agents has been developed that allows the targeting of tumor cells in a specific manner (15, 16). Although the purpose of these molecules has generally been drug delivery, their tumor specificity could also be exploited to enhance intraoperative imaging. Our initial studies were based on a compound known as HN-1, TSPLNIHNGQKL, which has previously been shown to be internalized and is cytotoxic to cancer cells when conjugated to a toxin or inhibitory peptide (17–19). HN1 is a phage-derived peptide targeted initially to HNSCC cell lines. Its ability to internalize, requirement for micromolar concentrations, and fairly slow internalization (typically 24 hours) have been duplicated in other laboratories, and are suggestive of cell-penetrating peptides, although the mechanism is currently unknown (20). Further development and labeling with IRDye-800 led to Compound-17 described in this work.

In this study, we describe the properties of the IRDye-800–labeled HN-1 analog, called Compound-17, in a biological context. We demonstrate that this peptide has high affinity for two MTC cells in vitro and in vivo. The binding dynamics suggest the molecule behaves as a cell-penetrating peptide, which may associate with mitochondria of MTC cells. Our studies in a murine flank xenograft model verified the in vitro results, albeit with background fluorescence. To examine imaging with this molecule in situ, we established an orthotopic xenograft model of MTC using techniques that have been previously successful for differentiated thyroid cancer orthotopic models (21). This model allows us to examine localization of the imaging agent in a natural MTC setting by using existing vasculature and tumor microenvironment. It also decreases background fluorescence seen by our compound in the gastrointestinal and renal systems. We found that in both in vivo models of MTC (flank xenografts and orthotopic xenografts), the imaging peptide resulted in significant fluorescence at the site of the xenograft. We propose that this imaging molecule may have potential application to enhance surgical removal of MTC.

Materials and Methods

Conjugation of the IRDye-800

The labeled peptide was synthesized by standard solid state peptide synthesis. IRDye-800-NHS ester (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used to label the N-terminal monoprotected peptide in dimethyl sulfoxide and 4-methyl morpholine, using equimolar dye and peptide. The product was purified by reverse-phase C-18 high-performance liquid chromatography column to produce the desired monolysine-labeled product, which was lyophilized. The product had a single high-performance liquid chromatography peak on a C-18 column (>90% area by NIR800 emission detection of the dye).

Culture of cell lines

MZ-CRC1 cells were obtained from R. Gagel (MD Anderson, Houston, TX). TT cells were obtained from B. Nelkin (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). All cells were verified mycoplasma free by PCR. All cells were verified to be of thyroid origin by short tandem repeat profiling (22). Twenty thousand cells were plated on clear-bottom/black-plate 96-well (Corning Costar; 3603), and allowed to attach for 24 hours at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated serum (Gibco; Catalog 10437-028), 1% minimum essential medium nonessential amino acids (Gibco), and 1% l-glutamine (Gibco; Catalog 25030-164).

In vitro binding assay

Cells were rinsed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with media without supplemental fetal bovine serum for the remainder of the experiment. Cells were incubated for 2 hours in 10 µM Compound-17 at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Following incubation with Compound-17, cells were rinsed three times in 1× PBS, then lysed in M-PER (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with aprotinin (1 µg/mL), leupeptin (1µg/mL), pepstatin (1µg/mL), 20 µM Amidinophenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (APMSF), and 0.3 µM okadaic acid. Lysates were immediately examined on a Synergy H4 Hybrid Multimode Microplate Reader (BioTek).

Microscopy

A total of 6 × 104 cells was cultured on coverslips. Cells were carefully rinsed with 1× PBS and incubated in serum-free RPMI 1640 media with 10 µM Compound-17 and 200 µM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were then incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber for 1 hour. Stained cells were then rinsed in 1× PBS and incubated in serum-free RPMI 1640 media for 30 minutes. Cells were then rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% formalin for 10 minutes and coverslips were mounted using Duolink II Mounting Medium with 4,6-diamidino-2-DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All images were acquired at ambient temperature using an Olympus IX-81 microscope, with a 63× or 100× Plan Apo oil immersion objective (1.4 numerical aperture), and a QCAM Retiga Exi FAST 1394 camera, and analyzed using the Slidebook software package (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Subcutaneous xenografts

Cells were removed from the 10-cm3 tissue culture dish by incubation with 0.25% trypsin EDTA (Gibco). Cells were rinsed in 1× PBS and resuspended at 1 × 107 cells/mL in 1× PBS. For each of two cell lines (TT and MZ-CRC1), one million cells of each cell line were then combined with 100 µL matrigel and injected into separate flanks (TT-right; MZ-CRC1 left) of athymic nude mice (5 weeks old, obtained from Target Validation Shared Resource at Ohio State University). Development of tumors was monitored by visual examination until volumes could be determined by caliper measurements. Tumor volumes were determined using the following formula: tumor volume = 1/2 × [length × width (2)] (23). Once both tumors reached a minimum volume of 150 mm3, the animals were injected with 40 nmol Compound-17 via tail-vein injection. Animals were imaged using CRi Maestro at 3, 6, 24, 36, and 48 hours following the injection.

Near-IR fluorescence imaging

Forty-eight hours after injection, the animals were euthanized and skinned for imaging. The tumors along with internal organs were removed for imaging. The animals were imaged using both a CRi Maestro white light excitation imager (CRi, Woburn, MA) and a laser excitation FluobeamTM 800 NIR imaging system (Fluoptics, Grenoble, France). Comparisons between tissues were made by placing all tissues relevant to the comparison in the same image to equalize exposure time.

MTC orthotopic xenograft

Cell preparations and injection protocol

Cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin EDTA to remove from culture dishes. Cells were rinsed and resuspended in 1× PBS at 5 × 107 cells/mL and kept on ice. Athymic nude mice (∼5 to 6 weeks; Target Validation Shared Resource at Ohio State University) were anesthetized with isofluorane and skin sterilized by use of 4% chlorhexidine (Henry Schein Animal Health, Columbus, OH). A sterile field was established, and a vertical cervical incision was made. Visualization was achieved by use of a dissecting microscope. Strap muscles and submandibular glands were separated and reflected, respectively, using blunt dissection. Once trachea and thyroid were adequately visualized, and 10 μL cell suspension was injected into the target thyroid lobe using an insulin syringe needle (27 ga; Terumo, Somerset, NJ). Submandibular tissue was reapproximated, and the incision was closed by use of 6-0 absorbable surgical sutures. Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia, returned to their cage, and supplied with analgesics (2 mg/mL ibuprofen) for 7 days. All animal studies were done under protocols approved by Ohio State University Laboratory Animals Recourse.

US monitoring

Animals were examined weekly, starting the second week after injection, using a VisualSonics Vevo2100 system (Toronto, Canada). Mice were anesthetized as described previously. Three-dimensional images were obtained by use of a three-dimensional motor attachment. Aquasonic 100 gel (Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, NJ) and a MS-550D transducer were used to acquire images. The default Cardiac package was used for general imaging. Transducer probe was set at 32 Hz and 80% power. The two-dimensional gain was set at 20DB, with scan distance at 8 mm and scan size set at 0.05 mm. Volumes were calculated using the VeVo Laboratory suite.

Tissue collection

Following euthanasia, blood was collected for serum preparation. Tumors, along with heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract, were excised. Tumor(s) was measured by calipers to determine final volume using the following formula: (4/3) × π × (length/2) × (width/2) × (height/2).

Calcitonin

To obtain blood serum, blood-obtained posteuthanasia was allowed to clot for 15 minutes at room temperature and then centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes to separate serum from clotted blood. Serum was stored at −80°C for no more than 3 months while all experiments were completed. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay procedure was performed following manufacturer’s (Biomerica, Irvine, CA) instructions. Briefly, wells were prepared, and reagents were added, combined with thawed serum, and incubated at room temperature for 4 hours. After rinsing and adding a colorimetric reagent, the plate was examined on a Dynatech MR7000 plate reader (Guernsey, UK) at 405 nm and at 450 nm. Data were input into a spreadsheet program for analysis.

H&E and calcitonin staining

Tumors and tissues were fixed in 10% zinc formalin (Thermo Scientific) for 3 days and then paraffin embedded and sectioned (4 µm). H&E staining was performed by the Solid Tumor Pathology Core at Ohio State University, as described previously (24). Calcitonin antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), and staining was performed using a 1:400 dilution of the primary antibody.

Statistical analysis

Wilcoxon rank–sums test was used to compare calcitonin levels between age-matched noninjected mice and mice bearing a xenograft. Spearman correlation was calculated for calcitonin concentration and the volume at necropsy.

Compound-17 in orthotopic xenografts

A total of 40 nmol Compound-17 was injected into the animal via tail-vein injection. The animals were imaged using both a CRi Maestro white light excitation imager and a laser excitation FluobeamTM 800 NIR imaging system (Fluoptics, Grenoble, France). Tumors and equal volume of muscle tissue were excised and compared for fluorescence.

Results

In vitro characterization of Compound-17 MTC interaction

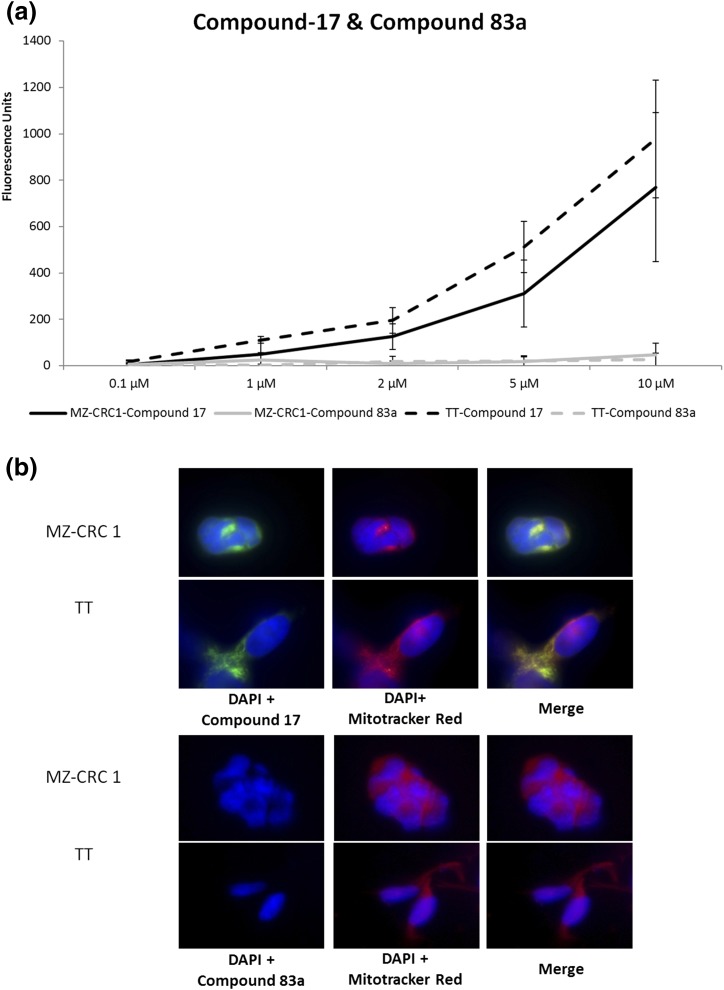

We examined the ability of Compound-17 to bind to two MTC cell lines in vitro. MTC cells were exposed to Compound-17 and were compared with both nontreated control cells and cells treated with a negative control (Compound-83a), which is a sequence-jumbled version of the amino acids in HN-1 and Compound-17. Both MTC cell lines exposed to Compound-17 showed fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner, so that increasing concentration of Compound-17 correlated with increased fluorescence intensity. In contrast, cells exposed to Compound-83a had no detectable fluorescence [Fig. 1(a)]. TT cells were slightly better at binding/engaging/internalizing Compound-17 than MZ-CRC1 cells [Fig. 1(a)].

Figure 1.

(a) Increased fluorescence is proportional to compound concentration. A scrambled control (Compound-83a) does not show fluorescence, indicating this compound does not interact with MTC cells in vitro. This increase in fluorescence in micromolar range suggests activity as a cell-penetrating peptide. Results shown are the mean of three independent experiments. (b) In vitro fluorescence of Compound-17 in MTC cells. Imaging of individual MTC cells indicates that Compound-17 staining overlaps with mitochondria in MTC cells. Fluorescence from Compound-83a cannot be detected in MTC cells (bottom).

We examined the subcellular localization of Compound-17 in the MTC cells. MTC cells were incubated with Compound-17 and Mito-tracker. Figure 1(b) shows localization of Compound-17 (shown in green) and the mitochondria (Mito-tracker in red) in both MTC cell lines. Localization of Compound-17 in a similar location with Mito-tracker (yellow overlay) suggests that it colocalizes with mitochondria.

Characterization of Compound-17 in a MTC subcutaneous flank xenograft model

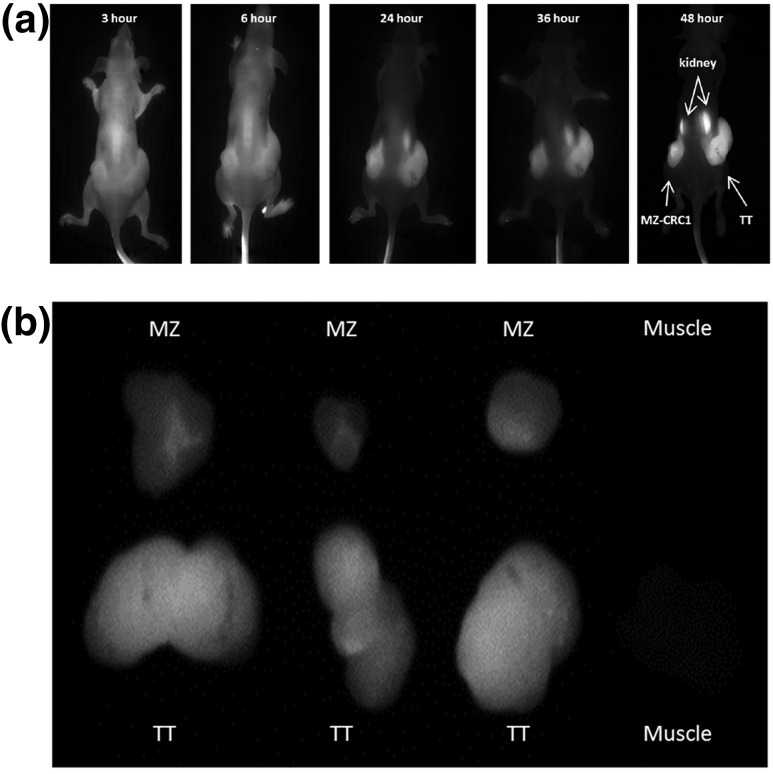

We examined the localization of Compound-17 in a subcutaneous flank xenograft model for both MTC cells. Tumors that were at least 150 mm3 were used in the experiment. Compound-17 was distributed relatively equally throughout the body in the 3- and 6-hour images [Fig. 2(a)]. Beginning at 24 hours and through the end of the experiment (48 hours) revealed retention of the agent in the tumor xenografts compared with the rest of the body, leading to improved visualization of xenografts over time [Fig. 2(a)]. As observed in Fig. 2(a), uptake is generalized in early time points, and increased signal-to-background in the xenografts is observed at later time points. We made future observations using the 24- to 48-hour time points because of the better target-to-background ratio. Both cell lines appear to be equally capable of concentrating Compound-17 within the corresponding xenograft [Fig. 2(a)].

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence of Compound-17 in MTC flank subcutaneous xenograft models. Forty-eight hours after injection, mice were euthanized, and an image was taken after skin removal (upper panel). The images were obtained on CRi Maestro white light excitation imager, as described in Materials and Methods. (b) Increased concentration of Compound-17 was observed in tumor (lower left) in comparison with muscle tissue. The highest concentration in organs was observed in kidneys (lower right panel), although some fluorescence could be observed in the lung and gastrointestinal tract. The images were obtained with FluobeamTM 800 NIR imaging system, as described in Materials and Methods.

To examine whether the compound was retained nonspecifically within other organs, at 48 hours the animals were euthanized and the internal organs from the animal were removed and examined ex vivo for fluorescence. We found increased fluorescence in the MTC xenografts compared with size-matched muscle tissue [Fig. 2(b), left panel] and with heart and lung [Fig. 2(b), right panel]. Increased fluorescence was observed in kidneys relative to muscle and other tissues, consistent with renal excretion [Fig. 2(b), right panel].

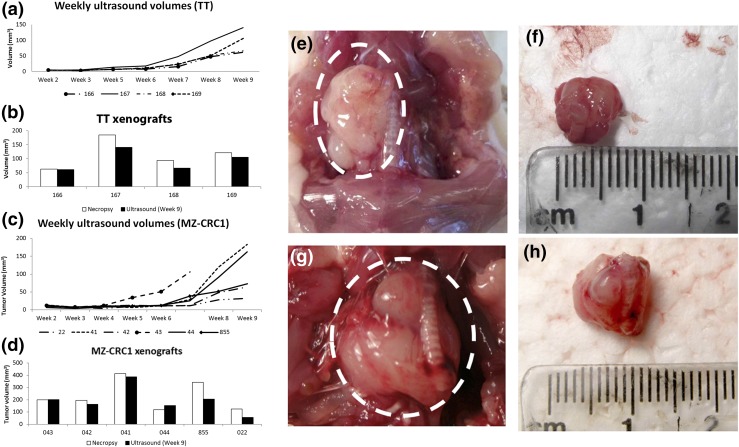

Characterization of MTC orthotopic xenografts

To examine the concentration of Compound-17 in the thyroid microenvironment, we established orthotopic xenografts for both TT and MZ-CRC1 cell lines by injecting each cell line into the thyroid lobes of five (TT) or six (MZ-CRC1) animals. Xenografts were successfully established in all animals injected with the TT cell lines, and in five of six of the animals injected with the MZ-CRC1 cell line. Growth of the xenografts was followed weekly with three-dimensional US starting at the second week after injection. Orthotopic xenografts were detectable as early as 3 weeks as a small hypodense nodule in the injected thyroid lobe (data not shown). As the xenografts enlarged, they took on a round contour and remained hypodense compared with surrounding tissues. Larger tumors were observed to extend to the contralateral side of the neck posterior to the trachea and esophagus. There was little variability in growth between each orthotopic xenograft in animals injected with TT cells [Fig. 3(a)]. Some difference was observed in final volume of orthotopic xenografts as calculated by the US software and volumes determined by caliper measurements following necropsy in xenografts derived from MZ-CRC1 cells [Fig. 3(c)].

Figure 3.

(a) TT orthotopic xenograft in situ. (b) TT orthotopic xenograft ex vivo. (c) MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenograft in situ. (d) MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenograft ex vivo. (e) Volumes of TT orthotopic xenografts as calculated by US imaging. (f) Volume comparison of TT orthotopic xenografts by US at 9 weeks and by caliper measurement at necropsy. (g) Volumes of MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenografts as calculated by US imaging. (h) Volume comparison of MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenografts by US at 9 weeks and by caliper measurement at necropsy.

Ex vivo examination of MTC orthotopic xenografts

Orthotopic xenografts were allowed to grow for 9 weeks prior to necropsy. Photo documentation was obtained both in vivo and ex vivo en block with trachea with representative animals from each cell line shown in Fig. 3(e–h). Growth of the tumors was noted to be either spherical or mildly lobulated and well encapsulated [Fig. 3(e–h)]. Invasion into surrounding tissues was not observed [Fig. 3(e–h)]. Mass effect on the trachea and thyroid was observed in some animals [Fig. 3(e–h)]. These tumors did not demonstrate high vascularity [Fig. 4(a)]. Final US were performed 3 days prior to necropsy.

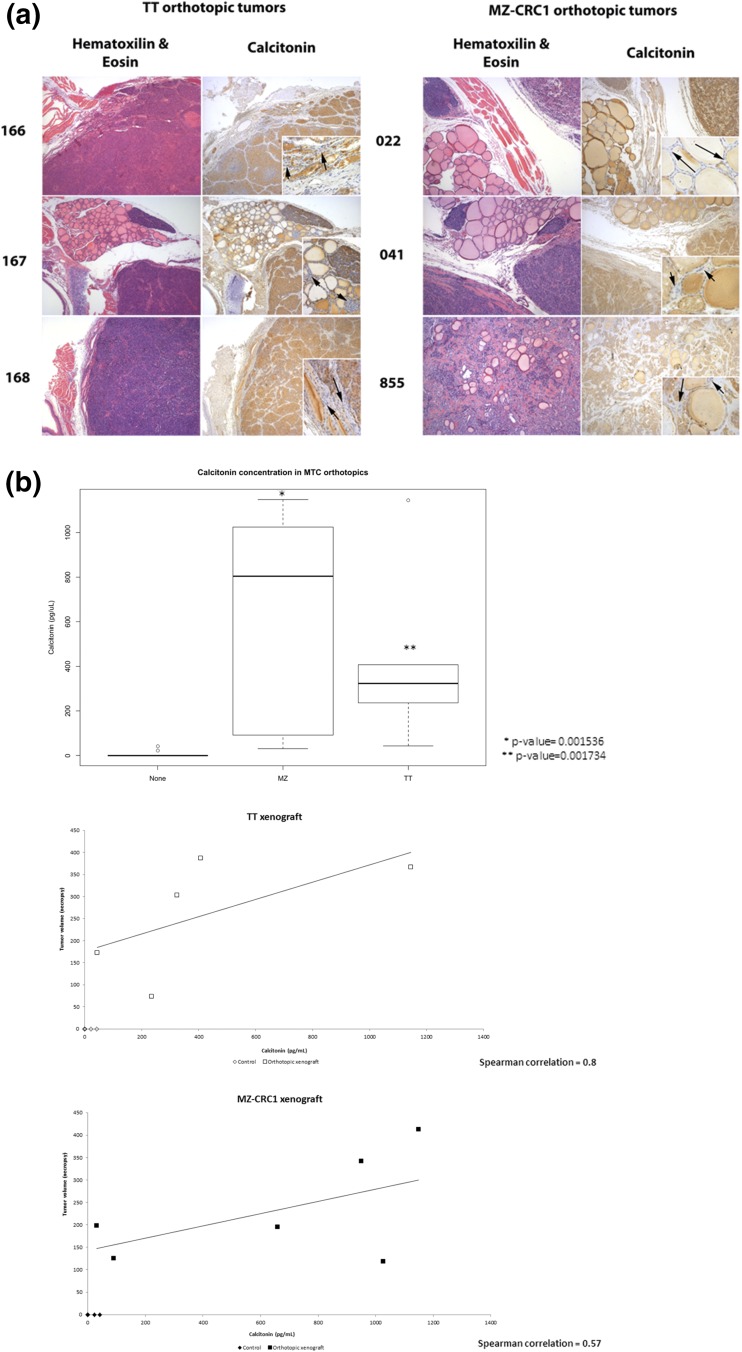

Figure 4.

(a) Histological examination of orthotopic xenografts. Orthotopic xenografts developing from both MTC cell lines grow intrathyroidal (TT, 166 and 168; MZ-CRC1, 855) and adjacent to the thyroid (TT, 167; MZ-CRC1, 022 and 041). Calcitonin staining confirms origin of tumors as calcitonin-producing TT or MZ-CRC1 cells. Insets show that follicular cells are negative for calcitonin staining in the remaining normal tissue. Arrows within insets indicate unstained follicular cells. (b) Calcitonin concentration is increased in mice bearing MTC orthotopic xenografts. Wilcoxon rank test comparison showed increased serum calcitonin levels of orthotopic xenograft-bearing mice compared to controls. Necropsy tumor volumes also correlated with calcitonin levels. Spearman correlation was moderately positive for MZ-CRC1 tumors (0.57) and strongly positive for TT (0.8).

Histological examination of MTC orthotopic xenografts

Tumors were sectioned and processed for histologic examination. In some orthotopic xenografts, as shown in Fig. 4(a) (166, 168, and 855), tumor cells were seen growing around thyroid follicles. A capsule of connective tissue is seen around the xenografts. It is unclear whether this connective tissue is a host reaction or derived from the thyroid capsule, accommodating the growth of the tumor. Vasculature is seen coursing through the surrounding connective tissue, but the xenograft does not appear very vascular and no vascular invasion was observed. No metastasis to lymph nodes was observed, although tumors were removed en block with the trachea but not surrounding tissues, and consequently, lymph nodes were not present in sections used for histological analysis. Calcitonin staining was also performed, demonstrating expression of calcitonin in the orthotopic xenografts. Histology using calcitonin has confirmed that most of the component cells of the xenograft are derived from C-cells [Fig. 4(a)]. Although the colloid retains the secondary staining in the adjacent normal thyroid (where present), the follicular cells surrounding those follicles are negative for calcitonin immunoactivity [insets, Fig. 4(a)]. Histologic examination was also performed in brain, lung, and liver stained. No metastasis to these organs was observed (data not shown).

Examination of serum calcitonin levels for MTC orthotopic xenograft-bearing mice

There was a significant increase in calcitonin levels of mice bearing MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenografts (P value = 0.001536) and in mice bearing TT orthotopic xenografts (P value = 0.001734) compared with age-matched controls [Fig. 4(b)]. We also examined the relationship between the tumor volume at necropsy and calcitonin concentration in the serum and found a moderate correlation between tumor volume and serum calcitonin concentration in MZ-CRC1 xenograft-bearing mice (Spearman = 0.57) and a strong correlation between xenograft volume and serum calcitonin concentration in TT xenograft-bearing mice (Spearman = 0.8) [Fig. 4(b)].

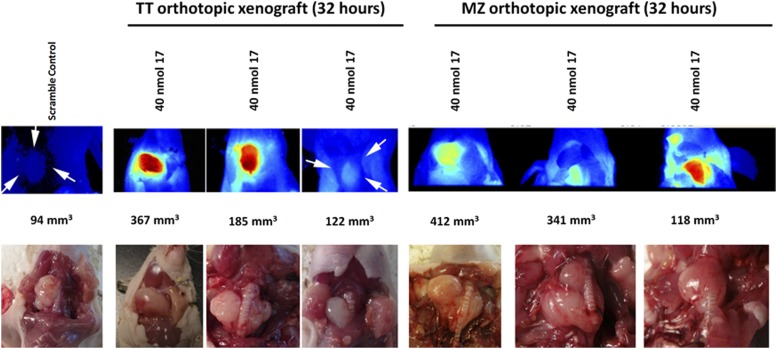

Imaging of Compound-17 in a MTC orthotopic model

We used the previously described orthotopic xenograft to examine the ability of Compound-17 to accumulate at the site of the orthotopic xenograft. Using the fluorescently labeled Compound-17, we determined that the compound concentrated in the orthotopic xenograft following tail-vein injection, although there was some variability between the different mice in part related to the size of the xenograft (Fig. 5). Importantly, surrounding tissue did not fluoresce, indicating that Compound-17 specifically is internalized/binds to tumor cell–derived xenografts. Mice injected with sequence-jumbled control (Compound-83a) did not have specific (or indeed, any detectable) fluorescence (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

High fluorescence observed in TT and MZ-CRC1 orthotopic xenografts. A total of 40 nmol Compound-83a (left, scramble control) or Compound-17 was injected by tail vein. The images were obtained following animal euthanasia and exposure of the orthotopic xenograft by neck incision 48 hours after injection. Images were obtained on CRi Maestro white light excitation imager, as described in Materials and Methods. Compound-17 allows imaging of orthotopic xenografts, whereas little to no fluorescence is observed in scrambled control or surrounding tissues of Compound-17–injected mice. The bottom panel includes bright field images of the orthotopic xenografts in situ following fluorescence imaging. White arrows indicate the location of the xenograft.

Discussion

We report the biological evaluation of a near-IR imaging molecule in MTC. Our initial experiments show that this molecule can bind and/or be internalized in two MTC cell lines using an in vitro assay. Microscopic evaluation using the same assay, along with the relatively high concentration needed for rapid internalization, suggests that the molecule behaves as a cell-penetrating peptide (11, 20, 25). We examined cellular localization of Compound-17 in MTC cells using fluorescence microscopy and found that fluorescence in treated cells coincided with localization of mitochondria. This localization may be due to internalization at that location or to localization of a fluorescent metabolite at that location. The negative control compound (83a) demonstrated virtually no fluorescence in vitro, indicating specificity of Compound-17. The mechanism by which Compound-17 binds to and enters the cells is presently unknown. Hong and Clayman (15) described a peptide called HN1, which they found to be concentrated in squamous cancer cells most likely via receptor-mediated endocytosis, but that mechanism was not fully characterized. Compound-17 is partially derived from the same amino acids and may have a similar entry mechanism, but is far more rapidly taken up (H. Ding, et al., unpublished observation). Other cell-penetrating peptides are internalized through interactions with integrins (26). Considering the apparent localization of Compound-17 to the mitochondria, there are a number of mitochondrial substances that may be important for its retention in the cell. For example, LyP-1, a cell-penetrating peptide previously described, is bound by p32, a mitochondrial chaperone protein that is responsible for oxidative phosphorylation (27–29). In cells with very high metabolic activity, such as cancer cells, p32 is expressed at the cell membrane and not in the mitochondria, like in normal tissues.

We also observed specific fluorescence in flank xenografts in vivo [Fig. 2(a)] and ex vivo [Fig. 2(b)] that demonstrated excellent signal-to-background ratio over the time examined and renal excretion. Interestingly, the agent appears to diffuse equally and extensively through the entire tumor with different retention rates. The agent does not appear to be retained in or near the blood vessels or lymphatics. This could potentially lead to a more complete visualization of all tumor tissues, and not just the highly vascularized area of the tumor, although this requires further studies to confirm.

To better evaluate the practicality of Compound-17 in an intraoperative setting, we developed an orthotopic model of MTC in mice. Xenografts were established by direct injection into the thyroid bed during survival surgery, as previously described for various thyroid cancer cell lines (30–33). This allowed xenograft growth and development in a microenvironment that includes surrounding thyroid follicular cells, vasculature, and paracrine signaling. We confirmed the orthotopic location of the xenografts by murine neck US, which provides a noninvasive method similar to that used in humans. Alternative monitoring systems typically use bioluminescence, which requires genetically altered cells. MTC cell lines are slow growing, and the process of introducing a luciferase gene may have detrimental effects, including the selection of subclones. Because of tumor heterogeneity and the nuance of using US, there may have been some animals that had incomplete US imaging of their tumors, and, as a result in those cases, the total volume of the tumors on three-dimensional US underestimates the actual disease burden. Although there is a learning curve in using US for this application, it is a valuable tool that allows use of unlabeled cell lines and is noninvasive. Overall, we found that growth curves are smooth and consistent among animals, and that the volume of the tumors as recorded at final US closely approximates the volumes as measured during necropsy. Whereas reports of papillary thyroid carcinoma and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma orthotopic xenografts suggest large xenografts (100 to 200 mm3) in 4 to 5 weeks (33), MTC orthotopic tumors achieved those large volumes between 9 and 10 weeks, correlating with their slow growth in vitro. Another helpful adjunct in evaluating tumor growth in the MTC orthotopic model is the measurement of serum calcitonin via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Calcitonin is a useful biomarker in humans with MTC (34). In animals with MTC xenografts, we found increased calcitonin concentrations compared with age- and sex-matched control animals. Although this was not applicable to the evaluation of Compound-17 in these animals, this served as a proof of concept that calcitonin was produced by the tumors and could potentially be used as a biomarker for pharmacodynamics measure of drug activity or response to therapy.

The use of Compound-17 in the MTC orthotopic model demonstrates its potential application in surgical resection. The tumors demonstrate intense fluorescence compared with surrounding tissues. There is minor background fluorescence in the surrounding muscle, trachea, and esophagus. In patients with widespread locoregional disease as well as in patients with locoregional recurrence in the operative setting, this level of resolution would prove valuable in differentiating scar tissue from active disease. This level of differentiation may be even more valuable in sensitive regions such as around the recurrent laryngeal nerve and other cranial nerves during lateral neck dissection. The ability to discriminate between malignant and nonmalignant tissue in real time without the need for biopsy is the ultimate goal to minimize risk to the patient and to obtain a more complete resection. Although Compound-17 is an excellent candidate, further studies are necessary to move it forward for use in humans as well as to maximize its potential in other applications. This includes evaluating its breadth of sensitivity and specificity, mechanism of action, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, and tolerability. Determining the optimal timing of administration of the compound prior to imaging is needed to maximize the signal-to-background ratio. Although there is appreciable work to be done, Compound-17 appears to have the potential for a significant impact for patients with MTC.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ohio State University-Comprehensive Cancer Center Target Validation Shared Resource and Small Animal Imaging Core for use of facilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health SPORE Grant P50CA168505 (to M.D.R.), Pelotonia Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (to K.K.R.), and Career Development Program Grant P50CA168505 from National Institutes of Health SPORE (to J.E.P.). We also acknowledge support from National Cancer Institute Grant P30CA016058 and the Stefanie Spielman Foundation (to M.F.T.). C.L.W. and M.F.T. are also supported by the Wright Center of Innovation in Biomedical Imaging and Ohio TECH 10-012. C.L.W. is supported by the following: Award UL1TR000090 from the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences (the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health); Richard P. and Marie R. Bremer Medical Research Fund and William H. Davis Endowment for Basic Medical Research from Ohio State University Medical Center (the remarks and opinions are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Davis/Bremer Research Fund or Ohio State University Medical Center); and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Clinical Loan Repayment Program.

Author contributions: K.K.R. contributed to data acquisition and analysis/interpretation, and participated in preparation of the article. S.E.J. contributed to data acquisition and analysis/interpretation, and participated in preparation of the article. H.D., L.G., D.S., and M.S. contributed to data collection. C.L.W. contributed to the molecule design. S.K. synthesized the molecule. M.D.R., M.F.T., and J.E.P. participated in the conception and design of the study and revised and approved the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- FSA

- frozen sectioning analysis

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- IR

- infrared

- MTC

- medullary thyroid cancer

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PET

- positron emission tomography

- US

- ultrasound.

References

- 1.Fagin JA, Wells SAJ Jr. Biologic and clinical perspectives on thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1054–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells SA Jr, Asa SL, Dralle H, Elisei R, Evans DB, Gagel RF, Lee N, Machens A, Moley JF, Pacini F, Raue F, Frank-Raue K, Robinson B, Rosenthal MS, Santoro M, Schlumberger M, Shah M, Waguespack SG; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma . Revised American Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2015;25(6):567–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau NG, Haddad RI. Vandetanib for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(3):524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabanillas ME, Hu MI, Durand JB, Busaidy NL. Challenges associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy for metastatic thyroid cancer. J Thyroid Res. 2011;2011:985780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbeek HHG, Plukker JTM, Koopmans KP, de Groot JW, Hofstra RM, Muller Kobold AC, van der Horst-Schrivers AN, Brouwers AH, Links TP. Clinical relevance of 18F-FDG PET and 18F-DOPA PET in recurrent medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(12):1863–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotthardt M, Lohmann B, Behr TM, Bauhofer A, Franzius C, Schipper ML, Wagner M, Höffken H, Sitter H, Rothmund M, Joseph K, Nies C. Clinical value of parathyroid scintigraphy with technetium-99m methoxyisobutylisonitrile: discrepancies in clinical data and a systematic metaanalysis of the literature. World J Surg. 2004;28(1):100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008:pdb.prot4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen HJ; ALA-Glioma Study Group . Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stummer W, Novotny A, Stepp H, Goetz C, Bise K, Reulen HJ. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrins: a prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(6):1003–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen QT, Olson ES, Aguilera TA, Jiang T, Scadeng M, Ellies LG, Tsien RY. Surgery with molecular fluorescence imaging using activatable cell-penetrating peptides decreases residual cancer and improves survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4317–4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orosco RK, Savariar EN, Weissbrod PA, Diaz-Perez JA, Bouvet M, Tsien RY, Nguyen QT. Molecular targeting of papillary thyroid carcinoma with fluorescently labeled ratiometric activatable cell penetrating peptides in a transgenic murine model. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113(2):138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenthal EL, Warram JM, de Boer E, Basilion JP, Biel MA, Bogyo M, Bouvet M, Brigman BE, Colson YL, DeMeester SR, Gurtner GC, Ishizawa T, Jacobs PM, Keereweer S, Liao JC, Nguyen QT, Olson JM, Paulsen KD, Rieves D, Sumer BD, Tweedle MF, Vahrmeijer AL, Weichert JP, Wilson BC, Zenn MR, Zinn KR, van Dam GM. Successful translation of fluorescence navigation during oncologic surgery: a consensus report. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(1):144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tweedle MF. Peptide-targeted diagnostics and radiotherapeutics. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42(7):958–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall MV, Draney D, Sevick-Muraca EM, Olive DM. Single-dose intravenous toxicity study of IRDye 800CW in Sprague-Dawley rats. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12(6):583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong FD, Clayman GL. Isolation of a peptide for targeted drug delivery into human head and neck solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60(23):6551–6556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Un F, Zhou B, Yen Y. The utility of tumor-specifically internalizing peptides for targeted siRNA delivery into human solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(11):4685–4690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao L, Gorin MA, Zhang M, Ventura AC, Pomerantz WC, Merajver SD, Teknos TN, Mapp AK, Pan Q. Preclinical development of a bifunctional cancer cell homing, PKCepsilon inhibitory peptide for the treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5829–5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potala S, Verma RS. Targeting head and neck squamous cell carcinoma using a novel fusion toxin-diphtheria toxin/HN-1. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(2):1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright CL, Pan Q, Knopp MV, Tweedle MF. Advancing theranostics with tumor-targeting peptides for precision otolaryngology. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016;2(2):98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudas J, Idler C, Sprinzl G, Bernkop-Schnuerch A, Riechelmann H.. Identification of HN-1-peptide target in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011:140316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tran Cao HS, Kaushal S, Snyder CS, Ongkeko WM, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Real-time imaging of tumor progression in a fluorescent orthotopic mouse model of thyroid cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(11):4415–4422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweppe RE, Klopper JP, Korch C, Pugazhenthi U, Benezra M, Knauf JA, Fagin JA, Marlow LA, Copland JA, Smallridge RC, Haugen BR. Deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines reveals cross-contamination resulting in cell line redundancy and misidentification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4331–4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faustino-Rocha A, Oliveira PA, Pinho-Oliveira J, Teixeira-Guedes C, Soares-Maia R, da Costa RG, Colaço B, Pires MJ, Colaço J, Ferreira R, Ginja M. Estimation of rat mammary tumor volume using caliper and ultrasonography measurements. Lab Anim (NY). 2013;42(6):217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson FL, Cappellano CH. Histotechnology: A Self-Instructional Text. Chicago, IL: ASCP Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heitz F, Morris MC, Divita G. Twenty years of cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(2):195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruoslahti E. Tumor penetrating peptides for improved drug delivery [published online ahead of print April 1, 2016]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Fogal V, Zhang L, Krajewski S, Ruoslahti E. Mitochondrial/cell-surface protein p32/gC1qR as a molecular target in tumor cells and tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):7210–7218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fogal V, Richardson AD, Karmali PP, Scheffler IE, Smith JW, Ruoslahti E. Mitochondrial p32 protein is a critical regulator of tumor metabolism via maintenance of oxidative phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(6):1303–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yagi M, Uchiumi T, Takazaki S, Okuno B, Nomura M, Yoshida S, Kanki T, Kang D. p32/gC1qR is indispensable for fetal development and mitochondrial translation: importance of its RNA-binding ability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(19):9717–9737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nucera C, Nehs MA, Mekel M, Zhang X, Hodin R, Lawler J, Nose V, Parangi S. A novel orthotopic mouse model of human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2009;19(10):1077–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanden Borre P, Gunda V, McFadden DG, Sadow PM, Varmeh S, Bernasconi M, Parangi S. Combined BRAF(V600E)- and SRC-inhibition induces apoptosis, evokes an immune response and reduces tumor growth in an immunocompetent orthotopic mouse model of anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(12):3996–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonello ZA, Nucera C. Orthotopic mouse models for the preclinical and translational study of targeted therapies against metastatic human thyroid carcinoma with BRAF(V600E) or wild-type BRAF. Oncogene. 2014;33(47):5397–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison JA, Pike LA, Lund G, Zhou Q, Kessler BE, Bauerle KT, Sams SB, Haugen BR, Schweppe RE. Characterization of thyroid cancer cell lines in murine orthotopic and intracardiac metastasis models. Horm Cancer. 2015;6(2-3):87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bihan H, Becker KL, Snider RH, Nylen E, Vittaz L, Lauret C, Modigliani E, Moretti JL, Cohen R. Calcitonin precursor levels in human medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2003;13(8):819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]