Abstract

Context:

Total pancreatectomy followed by intrahepatic islet autotransplantation (TP/IAT) is performed to alleviate severe, unrelenting abdominal pain caused by chronic pancreatitis, to improve quality of life, and to prevent diabetes.

Objective:

To determine the cause of exercise-induced hypoglycemia that is a common complaint in TP/IAT recipients.

Design:

Participants completed 1 hour of steady-state exercise.

Setting:

Hospital research unit.

Patients and Other Participants:

We studied 14 TP/IAT recipients and 10 age- and body mass index–matched control subjects.

Interventions:

Peak oxygen uptake (VO2) was determined via a symptom-limited maximal cycle ergometer test. Fasted subjects then returned for a primed [6,6-2H2]-glucose infusion to measure endogenous glucose production while completing 1 hour of bicycle exercise at either 40% or 70% peak VO2.

Main Outcome Measures:

Blood samples were obtained to measure glucose metabolism and counterregulatory hormones before, during, and after exercise.

Results:

Although the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion did not differ between recipients and control subjects, aerobic capacity was significantly higher in controls than in recipients (40.4 ± 2.0 vs 27.2 ± 1.4 mL/kg per minute; P < 0.001). This difference resulted in workload differences between control subjects and recipients to reach steady-state exercise at 40% peak VO2 (P = 0.003). Control subjects significantly increased their endogenous glucose production from 12.0 ± 1.0 to 15.2 ± 1.0 µmol/kg per minute during moderate exercise (P = 0.01). Recipients did not increase endogenous glucose production during moderate exercise (40% peak VO2) but succeeded during heavy exercise, from 10.1 ± 0.4 to 14.8 ± 2.0 µmol/kg per minute (70% peak VO2; P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

Failure to increase endogenous glucose production during moderate exercise may be a key contributor to the hypoglycemia TP/IAT recipients experience.

TP/IAT recipients completed 1 hour of exercise and demonstrated deficient endogenous glucose production, which may explain the exercise-induced hypoglycemic episodes they experience.

Chronic pancreatitis with constant severe abdominal pain is a debilitating condition of various etiologies (1–3). It is often accompanied by diarrhea, weight loss, narcotic use, and severely impaired quality of life. Unsuccessful treatment regimens often continue 5 to 10 years before physicians resort to total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation (TP/IAT) (4), which is successful in reducing pain and narcotic use, improving quality of life, and avoiding diabetes caused by pancreatectomy (5–10). However, after TP/IAT many recipients experience hypoglycemic episodes (11, 12). Continuous glucose monitoring demonstrated that recipients experience blood glucose concentrations as low as 37 mg/dL (11). Repeated bouts of hypoglycemia result in symptom desensitization to low glucose levels and hypoglycemia unawareness (13, 14), which is extremely dangerous.

We have reported that exercise-induced hypoglycemia is common and has forced many recipients to eliminate moderate exercise-related activities that may lead to hypoglycemic episodes (11). During exercise euglycemia is maintained by reciprocal changes in insulin and glucagon secretion. Under normal physiologic conditions, as blood glucose concentrations begin to fall due to tissue utilization, glucagon secretion stimulates liver glycogenolysis to release glucose, which enters the systemic circulation and increases systemic blood glucose levels. It is not established how intrahepatically transplanted islets might affect the regulation of glycogenolysis. We have suggested that intrahepatically transplanted islets may imprecisely adjust insulin and glucagon secretion in relationship to systemic glucose levels because these islets are surrounded by free glucose during glycogenolysis (11).

In this study, we hypothesized that abnormalities in hepatic glucose production may contribute to the hypoglycemia recipients experience during exercise. TP/IAT recipients and control subjects completed an aerobic capacity test on a bicycle to standardize exercise intensity between subjects. Within a week, they returned for a 1-hour steady-state exercise session at 40% peak oxygen uptake (VO2). Some recipients returned for a higher-intensity exercise session at 70% peak VO2. A primed [6,6-2H2]-glucose infusion was used before, during, and after exercise to measure endogenous glucose production throughout each study.

Research Design and Methods

Recipients

After approval from the Western Institutional Review Board, 14 islet transplantation recipients and 10 age- and body mass index (BMI)–matched control subjects gave written, informed consent to participate in the study and were treated appropriately during the protocol.

Eleven of 14 recipients underwent TP/IAT at the University of Minnesota. Table 1 shows specific surgical details from each recipient’s TP/IAT. The surgical procedure of TP/IAT was performed as previously described (15). Briefly, the entire pancreas was resected, along with part of the duodenum, with gastrointestinal continuity restored by end-to-end duodenojejunostomy or Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy in the majority (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recipient Surgical Details From TP/IAT

| Recipient | Pylorus Spared | Distal Duodenum Spared | Roux-en-Y | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | No | Duodenojejunostomy |

| 2 | No | Yes | Yes | Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | No | Duodenoduodenostomy |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | No | Duodenoduodenostomy |

| 5 | Yes | No | No | Duodenojejunostomy |

| 6 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 7 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 8 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 9 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 10 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 11 | Yes | No | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 12 | Yes | No | No | Duodenojejunostomy |

| 13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy |

| 14 | Yes | Yes | No | Duodenojejunostomy |

Exercise protocol

Fourteen (12 female, 2 male) TP/IAT recipients and 10 (8 female, 2 male) healthy control subjects were studied. Ten of 14 recipients had a history of hypoglycemia with exercise. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 2. All recipients had islets infused into the hepatic portal vein [intrahepatic (IH)], and two of the recipients additionally had intraperitoneal islet placement [IH + intraperitoneal (IP)]. IP islet placement was used when the pressure in the hepatic portal vein became too high to safely infuse all the islets into the liver. Most of the recipients were insulin free; however, two recipients were using exogenous insulin to regulate glucose concentrations.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Islet Autotransplantation Recipients and Control Subjects Participating in the Exercise Study

| Recipients | Control Subjects | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (women/men) | 14 (12/2) | 10 (8/2) | |

| Age, y | 39 ± 3 | 35 ± 5 | 0.41 |

| Time since islet transplant, y | 5 ± 1 | — | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.6 ± 1.0 | 21.8 ± 0.8 | 0.19 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 0.02* |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 96 ± 2 | 86 ± 3 | 0.04* |

| RPE | 18.3 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 0.1 | 0.05* |

| Peak VO2, mL/kg per minute | 27.2 ± 1.4 | 40.4 ± 2.0 | <0.001* |

| Workload at 40% peak VO2, W | 46 ± 4 | 69 ± 7 | 0.003* |

Data are means ± standard error.

P < 0.05.

Day 1

All subjects underwent a symptom-limited maximal bicycle test to determine peak VO2 (16). Subjects exercised on a cycle ergometer. Oxygen consumption (L/minute and mL/kg per minute), carbon dioxide production (L/minute), and minute ventilation (L/minute) were measured via breath-by-breath analysis (Parvo Medics, Parvo Medics TrueOne 2400 Metabolic Measurement System; Sandy, UT). Data were recorded as an average over the preceding 15 seconds. Exercise was initiated at 20 W and increased by 30-W increments every 2 minutes until symptoms were maximal. Peak VO2 (mL/kg per minute) was recorded as the highest value over any 15-second period and in all cases corresponded to the value in the terminal portion of exercise. All subjects had heart rate, blood pressure, and electrocardiographic monitoring during the maximal bicycle test.

Day 2

On a separate day, but within a week, subjects returned after an overnight fast to undergo a constant level submaximal exercise test (16). Two intravenous catheters were inserted in the antecubital veins (unless the recipient had a venous port, in which case the port was used for drawing blood). A primed (12 mg/kg) [6,6-2H2]-glucose infusion (0.12 mg/kg per minute) was started 3 hours before exercise and continued until the protocol was complete. Subjects moved to the cycle ergometer 20 minutes before starting exercise (t = −20 minutes). At t = −5 minutes, subjects began breathing through the mouthpiece connected to the analyzer. Resting blood samples were drawn at t = −10, −5, and 0 minutes. Subjects began pedaling at a workload set to achieve 40% of each subject’s previously determined peak VO2. Because of the initial findings (see later) with a 40% VO2 workload, 8 of the 12 insulin-independent TP/IAT recipients returned on a different day for the 70% peak VO2 exercise session. Blood samples were drawn at t = 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after commencement of exercise. VO2 was measured continuously during the initial 15 minutes of exercise, and the cycle workload was adjusted as necessary during this period to achieve the desired VO2. Exercise was terminated after 60 minutes, and additional blood samples were drawn during recovery at t = 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after exercise. All protocols were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board, and all subjects gave written consent.

Assays and analytical techniques

Blood samples for measurement of plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, glucagon, and epinephrine were kept on ice and then centrifuged, and the plasma was separated and frozen at −80°C. Glucagon samples were collected in tubes containing Trasylol. Serum glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method (16, 17). Insulin, C-peptide, and glucagon were measured by radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Epinephrine was measured by adrenaline plasma enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (high sensitive) (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Plasma [6,6-2H2]-glucose was measured via gas chromatographic mass spectrometry.

Calculations

The systemic rate of endogenous glucose production (EGP) was calculated using Steele’s non–steady-state equation (18). EGP was calculated from the infusion rate of [6,6-2H2]-glucose and the ratio of [6,6-2H2]-glucose to endogenous glucose concentration (19, 20). Values from −30 to 0 minutes were averaged and considered basal for the insulin and C-peptide measurements.

Statistical analysis

The effect of exercise on metabolic and hormonal parameters between groups was analyzed by Student t test. Within each group, the effect of exercise was analyzed by one-factor analysis of variance for repeated measures followed by Fisher protected least significant difference for individual paired comparisons (Statview).

P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Recipients were 5 ± 1 years post–islet autotransplantation (Table 2). When we compared recipients and control subjects, there were no significant differences between age and BMI. The age range for control subjects was 22 to 62 years and for recipients was 23 to 58 years. Hemoglobin A1c was within normal range for both groups but significantly higher for recipients compared with control subjects (5.7 ± 0.2 vs 5.1 ± 0.1, respectively; P = 0.02). Fasting glucose was 96 ± 2 mg/dL in recipients and 86 ± 3 mg/dL for control subjects (P = 0.04).

Day 1

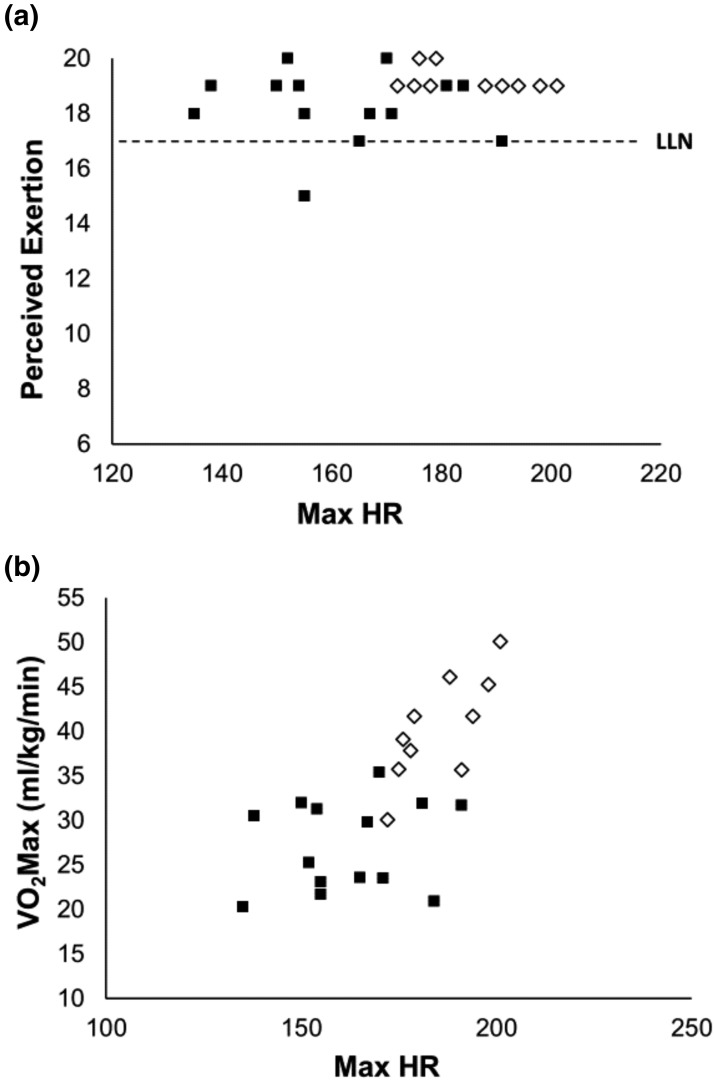

When we compared the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), recipients perceived they were exercising to their maximal capacity, although their values were slightly lower than those of the control subjects [Table 2, Fig. 1(a)]. RPE was 18.3 ± 0.4 in recipients and 19.3 ± 0.1 in control subjects (P = 0.05). However, these values were not consistent with their maximal heart rate during the aerobic capacity exercise test, which was significantly lower than that of the controls [Table 2, Fig. 1(b)]. This difference led to lower aerobic capacity results for recipients than for control subjects [Table 2, Fig. 1(b)]. Peak VO2 was significantly higher in control subjects than in recipients (40.4 ± 2.0 vs 27.2 ± 1.4 mL/kg per minute, respectively; P < 0.001), and that value was associated with a higher workload to reach 40% of peak VO2 (69 ± 7 vs 46 ± 4 W; P = 0.003; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Day 1. (a) Borg RPE vs maximum heart rate (HR). (b) Aerobic capacity (mL/kg per minute) vs maximum HR in TP/IAT recipients (black squares) and control subjects (open diamond). LLN, lower limit of normal for very hard to maximal exertion during exercise.

Day 2

Resting heart rate was 74 ± 4 beats per minute (bpm) for recipients and 66 ± 3 bpm for control subjects (P = ns). During the 1-hour steady state exercise session at 40% peak VO2, recipients and control subjects increased their heart rate to 111 ± 4 bpm and 117 ± 5 bpm, respectively (P = 0.30).

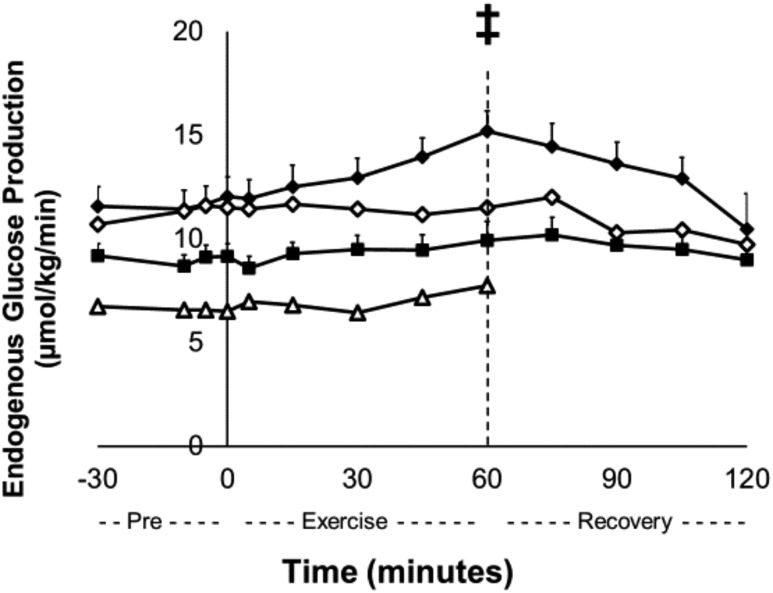

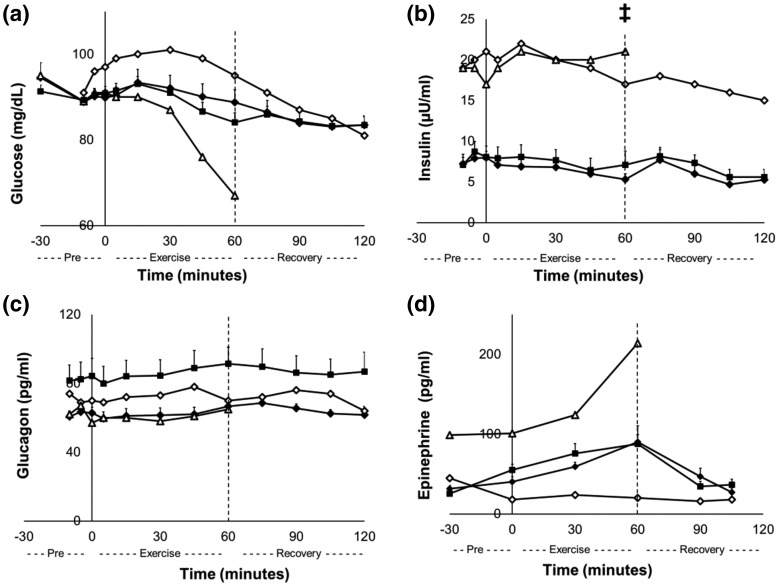

There were no significant differences in fasting plasma glucose between control subjects and insulin-independent recipients when exercising at 40% peak VO2. During exercise, EGP increased from 12.0 ± 1.0 µmol/kg per minute at minute 0 to 15.2 ± 1.0 µmol/kg per minute at minute 60 in the control subjects (P = 0.01), but EGP in the recipients did not change. The exercise protocol did not change EGP in the insulin-treated recipients, including the one who experienced low glucose levels (Fig. 2). Insulin-independent recipients reduced their blood glucose levels from 91 ± 2 mg/dL at the start of the exercise session (minute 0) to 84 ± 2 mg/dL at the end of the exercise session (minute 60; Δglucose, P < 0.001). One recipient experienced the onset of hypoglycemia, and her exercise protocol was promptly terminated early at 60 minutes [Fig. 3(a)]. This recipient was insulin-treated (12 units at bedtime and 1 unit/15 g carbohydrate at mealtime) and had elevated insulin [Fig. 3(b)] and low C-peptide levels (data not shown) throughout the protocol. In addition to the insulin-treated recipient who developed hypoglycemia, another recipient was using lower amounts of exogenous insulin (5 units at bedtime) and had higher insulin levels [Fig. 3(b)] but comparable C-peptide (data not shown) levels to control subjects and insulin-independent recipients. This recipient did not experience hypoglycemia with the exercise protocol [Fig. 3(a)]. With these two recipients who were taking exogenous insulin excluded, there were no differences in insulin levels between the control and recipient groups [Fig. 3(b)] or C-peptide levels (data not shown) throughout the protocol. However, the exercise protocol decreased insulin and C-peptide levels in control subjects from 8 ± 1 µU/mL to 5 ± 1 µU/mL and from 0.94 ± 0.08 ng/mL to 0.74 ± 0.06 ng/mL, respectively, from the start of exercise (minute 0) to the end of the exercise session (minute 60; P < 0.05); recipients did not change [P = ns; Fig. 3(b)]. Glucagon concentrations in recipients and controls were not significantly different from each other and did not change throughout the exercise protocol [Fig. 3(c)]. Glucagon concentrations in the insulin-treated recipients, including the subject who became hypoglycemic, did not change with the exercise protocol (11). Epinephrine concentrations did not change during the exercise protocol in either control subjects or insulin-independent recipients and did not differ significantly, except in the insulin-treated recipient whose glucose concentrations fell during exercise, who did have increased epinephrine concentrations during exercise [Fig. 3(a) and 3(d)].

Figure 2.

Day 2. Endogenous glucose production at rest, during exercise, and during recovery in TP/IAT recipients at 40% peak VO2. Control subjects (black diamonds), TP/IAT recipients (black squares), insulin-treated TP/IAT recipient 1 (open triangles), and insulin-treated TP/IAT recipient 2 (open diamonds). ‡P < 0.05: control subjects minute 0 vs minute 60. Data are means ± standard error.

Figure 3.

Day 2. (a) Blood glucose, (b) insulin, (c) glucagon, and (d) epinephrine at rest, during exercise, and during recovery in TP/IAT recipients at 40% peak VO2. Control subjects (black diamonds), TP/IAT recipients (black squares), insulin-treated TP/IAT recipient 1 (open triangles), and insulin-treated TP/IAT recipient 2 (open diamonds). ‡P < 0.05: control subjects minute 0 vs minute 60. Data are means ± standard error.

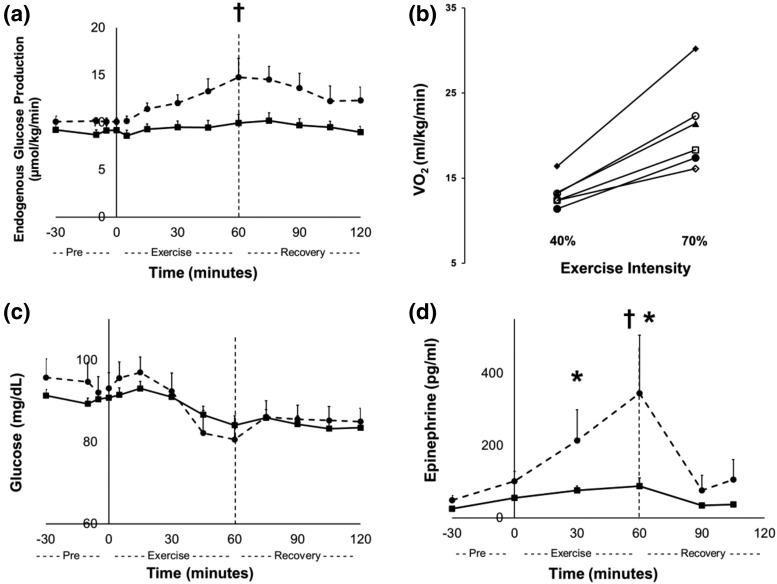

Because TP/IAT recipients had deficient EGP during moderate exercise (40% peak VO2), we examined the effects of a higher-intensity exercise protocol on EGP at 70% peak VO2 in 8 recipients. Six of these recipients successfully completed this second exercise protocol. During the 70% peak VO2 exercise session, EGP significantly increased, from 10.1 ± 0.4 µmol/kg per minute at minute 0 to 14.8 ± 2.0 µmol/kg per minute at minute 60 in recipients [P = 0.002; Fig. 4(a)]. However, this increase at 70% was no greater than control subjects developed at 40% peak VO2. As expected, recipients consumed more oxygen during the higher-intensity exercise protocol than at light exercise intensity [40% peak VO2; P = 0.003; Fig. 4(b)]. Epinephrine levels were significantly higher in recipients during the 70% peak VO2 compared with their 40% peak VO2 exercise session [minute 30 to 60; P < 0.05; Fig. 4(d)]. This finding is consistent with the greater perceived exertion that was reported during the 40% VO2 studies for the recipients and the control subjects. No differences were found between insulin, C-peptide, and glucagon levels during the 40% and 70% peak VO2 exercise sessions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of results at 40% and 70% peak VO2 in TP/IAT recipients. (a) Endogenous glucose production, (b) VO2, (c) blood glucose, and (d) epinephrine. Figures 4(a), 4(c), and 4(d) are at rest, during exercise, and during recovery in TP/IAT recipients. Black squares are recipients at 40% peak VO2, and black circles and dashed lines are recipients at 70% peak VO2. TP/IAT recipients at 70% peak VO2 minute 0 vs minute 60; †P < 0.05. TP/IAT recipients at 40% vs 70% peak VO2; *P < 0.05. Data are means ± standard error. In Fig. 4(b) each line represents a recipient who completed both 60-minute exercise sessions (six total). Two of eight recipients who began the 70% peak VO2 exercise session did not complete the 1-hour session. One hour of exercise at 70% peak VO2 increased recipient EGP from 10.1 ± 0.4 to 14.8 ± 2.0 µmol/kg per minute (P < 0.05), a level reached by the controls at 40% peak VO2 [Figs. 2 and 4(a)]. This level was associated with increased epinephrine levels in the recipients, which were not seen in controls at 40% peak VO2 [101 ± 28 to 360 ± 161; P < 0.05 vs 55 ± 7 to 88 ± 23 pg/mL; P = ns; Figs. 3(d) and 4(d)].

Discussion

In healthy exercising people blood glucose is regulated by insulin, glucagon, epinephrine, and the autonomic nervous system (21–25). In normal subjects exercise decreases insulin secretion and increases blood glucose (22). The role of the autonomic nervous system in regulating blood glucose is clear during exercise in healthy people whose islets receive pancreatic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves that are activated during exercise to downregulate insulin secretion. However, vagal innervations of islets seems unlikely to play a role in the regulation of blood glucose in TP/IAT recipients, given that transplanted islets are not likely to have physiologically meaningful vagal innervation.

These studies were performed to search for mechanisms that might explain why TP/IAT recipients have bouts of hypoglycemia when exercising moderately. Our approach used 1 hour of moderate exercise (40% peak VO2) in TP/IAT recipients and matched control subjects in combination with tracer-based measurement of EGP while blood samples were drawn for determination of EGP and for glucose, insulin, C-peptide, glucagon, and epinephrine. An important and unanticipated observation was made that although the Borg RPE was in the same range for the controls and recipients, maximal heart rates were lower in the recipients. The lower heart rate in the recipients was associated with a lower overall peak VO2. These data may indicate that recipients perceived the intensity of their exercise sessions differently than control subjects, which would be consistent with a history of chronic illness, feelings of diminished robustness, and a previous history of unrecognized mild hypoglycemia during exertion. The primary observation was that compared with control subjects, TP/IAT recipients had lower levels of EGP before exercise began, and, more importantly, they had no increase in EGP during exercise. One TP/IAT recipient developed hypoglycemia with an accompanying increase in epinephrine, but neither glucagon or EGP increased. In healthy people, the Borg RPE is a reliable measure of perceived effort during exercise (26, 27). An RPE of 17 to 20 indicates very hard to maximal exertion (28, 29), and both our recipients and control subjects believed they were in that range [Fig. 1(a)]. Given the deficiency in EGP seen at 40% peak VO2 in TP/IAT recipients, we restudied all available recipients at the higher-intensity exercise protocol (70% peak VO2). The higher-intensity exercise session succeeded in increasing EGP to the level seen in controls undergoing exercise at 40% peak VO2. Another difference was that the recipients had an increase in epinephrine levels at 70% peak VO2, in contrast to the lack of increased epinephrine levels in both controls and all but one recipient at 40% peak VO2. We suggest it was the increased epinephrine level that increased EGP at 70% peak VO2. Interestingly, type 1 diabetic recipients of intrahepatic alloislet transplant have not reported hypoglycemic episodes with exercise, but they have been reported to have higher epinephrine levels and higher EGP during hypoglycemic clamps (30). Intrahepatic alloislet recipients would be of interest to study during exercise, with recognition that there are important, complicating differences in these two groups. Alloislet recipients have type 1 diabetes, they do not undergo total pancreatectomy with surgical revision of the proximal small intestine, and they use immunosuppressive drugs, some of which cause abnormalities in beta cell function. Because of the important differences in these two groups, they should both be studied on the basis of their own merits with their own controls, which for the alloislet recipients would be matched type 1 diabetic subjects who have not had pancreatectomy but who do take immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. To the best of our knowledge, our data are the first to show that, compared with normal control subjects, TP/IAT recipients have low basal EGP and do not increase EGP during moderate exercise. This abnormality may contribute to the decrease in blood glucose TP/IAT recipients experience during moderate exercise. We do not mean to imply that deficient EGP caused hypoglycemia, the initiating mechanism for which remains obscure. But we do suggest that the failure of EGP to increase during mild exercise may contribute to hypoglycemia in the sense that it would deprive autoislet recipients of normal counterregulation of hypoglycemia during its onset.

Conclusions

Although TP/IAT is a highly effective treatment of chronic pancreatitis in alleviating pain and avoiding diabetes, some recipients experience exercise-induced hypoglycemia. This study has identified a deficiency in endogenous glucose production as a potential contributing mechanism for the hypoglycemic episodes TP/IAT recipients experience during exercise. Additionally, a difference in the Borg RPE between healthy subjects and recipients was uncovered. Additional studies are needed to fully explore the subtle differences between types, duration, and intensity of exercise and hypoglycemia in TP/IAT recipients. Understanding these interrelationships should enable physicians and recipients to better manage daily exercise without experiencing hypoglycemic episodes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Washington Pharmacy (Investigational Drug Services) and the Clinical Research Center and their nursing and support staff for assistance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1 39994 (R.P.R.), the American Diabetes Association Mentor-Based Grant (R.P.R.), and National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through Clinical and Translational Sciences Awards Program Grants UL1TR000423, KL2TR000421, and TL1TR000422.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- bpm

- beats per minute

- EGP

- endogenous glucose production

- IH

- intrahepatic

- IP

- intraperitoneal

- RPE

- Rating of Perceived Exertion

- TP/IAT

- intrahepatic islet autotransplantation

- VO2

- oxygen uptake.

References

- 1.Braganza JM, Lee SH, McCloy RF, McMahon MJ. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet. 2011;377(9772):1184–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta V, Toskes PP. Diagnosis and management of chronic pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(958):491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan S, Forsmark CE. Pain management in chronic pancreatitis: a treatment algorithm. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(3):323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland DER, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, Hering BJ, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Vickers SM, Bland B, Balamurugan AN, Freeman ML, Pruett TL. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(4):409–424, discussion 424–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondet JJ, Carlson AM, Kobayashi T, Jie T, Bellin M, Hering BJ, Freeman ML, Beilman GJ, Sutherland DE. The role of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(6):1477–1501, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh RM, Saavedra JR, Lentz G, Guerron AD, Scheman J, Stevens T, Trucco M, Bottino R, Hatipoglu B. Improved quality of life following total pancreatectomy and auto-islet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(8):1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, D’Alessio D, Choe KA, James LE, Gelrud A, Matthews JB, Rilo HL. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(5):680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcea G, Weaver J, Phillips J, Pollard CA, Ilouz SC, Webb MA, Berry DP, Dennison AR. Total pancreatectomy with and without islet cell transplantation for chronic pancreatitis: a series of 85 consecutive patients. Pancreas. 2009;38(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto S. Autologous islet cell transplantation to prevent surgical diabetes. J Diabetes. 2011;3(4):328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan K, Owczarski SM, Borckardt J, Madan A, Nishimura M, Adams DB. Pain control and quality of life after pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(1):129–133, discussion 133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellin MD, Parazzoli S, Oseid E, Bogachus LD, Schuetz C, Patti ME, Dunn T, Pruett T, Balamurugan AN, Hering B, Beilman G, Sutherland DE, Robertson RP. Defective glucagon secretion during hypoglycemia after intrahepatic but not nonhepatic islet autotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1880–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin YK, Faiman C, Johnston PC, Walsh RM, Stevens T, Bottino R, Hatipoglu BA. Spontaneous hypoglycemia after islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(10):3669–3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cryer PE. Mechanisms of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure and its component syndromes in diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3592–3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cryer PE. Mechanisms of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinnakotla S, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Radosevich DM, Arain M, Amateau SK, Mallery JS, Schwarzenberg SJ, Clavel A, Wilhelm J, Robertson RP, Berry L, Cook M, Hering BJ, Sutherland DE, Pruett TL. Factors predicting outcomes after a total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation lessons learned from over 500 cases. Ann Surg. 2015;262(4):610–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redmon JB, Kubo SH, Robertson RP. Glucose, insulin, and glucagon levels during exercise in pancreas transplant recipients. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(4):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadish AH, Litle RL, Sternberg JC. A new and rapid method for the determination of glucose by measurement of rate of oxygen consumption. Clin Chem. 1968;14(2):116–131. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele R, Bjerknes C, Rathgeb I, Altszuler N. Glucose uptake and production during the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes. 1968;17(7):415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah M, Law JH, Micheletto F, Sathananthan M, Dalla Man C, Cobelli C, Rizza RA, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Vella A. Contribution of endogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 to glucose metabolism after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes. 2014;63(2):483–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu R, Di Camillo B, Toffolo G, Basu A, Shah P, Vella A, Rizza R, Cobelli C. Use of a novel triple-tracer approach to assess postprandial glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(1):E55–E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen KF, Price TB, Bergeron R. Regulation of net hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis during exercise: impact of type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(9):4656–4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taborsky GJ Jr, Mundinger TO. Minireview: the role of the autonomic nervous system in mediating the glucagon response to hypoglycemia. Endocrinology. 2012;153(3):1055–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller RE. Pancreatic neuroendocrinology: peripheral neural mechanisms in the regulation of the islets of Langerhans. Endocr Rev. 1981;2(4):471–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahrén B, Taborsky GJ Jr, Porte D Jr. Neuropeptidergic versus cholinergic and adrenergic regulation of islet hormone secretion. Diabetologia. 1986;29(12):827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Diaz R, Caicedo A. Novel approaches to studying the role of innervation in the biology of pancreatic islets. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42(1):39–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eston RG, Williams JG. Reliability of ratings of perceived effort regulation of exercise intensity. Br J Sports Med. 1988;22(4):153–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loe H, Rognmo O, Saltin B, Wisloff U.. Aerobic capacity reference data in 3816 healthy men and women 20–90 years. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(5):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noble BJ. Clinical applications of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borg G, Lane B, Rhoda J, eds. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickels MR, Peleckis AJ, Markmann E, Dalton-Bakes C, Kong SM, Teff KL, Naji A. Long-term improvement in glucose control and counterregulation by islet transplantation for type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4421–4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]