Abstract

Human FCP1 in association with RNAP II reconstitutes a highly specific CTD phosphatase activity and is required for recycling RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) in vitro. Here we demonstrate that targeted recruitment of FCP1 to promoter templates, through fusion to a DNA-binding domain, stimulates transcription. We demonstrate that a short region at the C-terminus of the FCP1 protein is required and sufficient for activation, indicating that neither the N-terminal phosphatase domain nor the BRCT domains are required for transcription activity of DNA-bound FCP1. In addition, we demonstrate that the C-terminus region of FCP1 suffices for efficient binding in vivo to the RAP74 subunit of TFIIF and is also required for the exclusive nuclear localization of the protein. These findings suggest a role for FCP1 as a positive regulator of RNAP II transcription.

INTRODUCTION

RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) is a multisubunit enzyme responsible for transcription of protein coding genes in eukaryotes. The phosphorylation state of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest RNAP II subunit plays an important role in the regulation of transcript elongation (1,2). The elongation efficiency of RNAP II is regulated at least in part by dedicated protein kinases and phosphatases that establish the level of CTD phosphorylation. Two forms of RNAP II can be found in all eukaryotes (3). The form containing the phosphorylated CTD is called RNAP IIO. A second form contains an unphosphorylated CTD and is known as RNAP IIA. RNAP IIO catalyzes transcript elongation, while completion of the transcription cycle is dependent on dephosphorylation of RNAP IIO (1–6).

Recently a more complex CTD cycle in which different modified forms predominate at different stages of transcription has been suggested. It has been found that RNAP IIO phosphorylated at Ser5 is localized to promoters, whereas Ser2 phosphorylation occurs primarily during transcription elongation or termination (7). The CTD appears to be the regulatory focus of many factors which regulate mRNA processing (8–11). Moreover, several lines of evidence suggest that an interplay between positive and negative factors regulates transcription elongation. To date, one positively (P-TEFb) and two negatively acting (NELF and DSIF) factors have been identified. P-TEFb (positive transcription elongation factor) is a cyclin-dependent kinase composed of CDK9 and the regulatory partner cyclin T (12–15). Mammalian NELF (negative elongation factor) is a multiprotein complex with potential RNA-binding activity, while mammalian DSIF (DRB-sensitive inducing factor) is the homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spt4 and Spt5 proteins (16–18). Recent studies suggest that DSIF and NELF negatively regulate elongation through interaction with RNAP IIA and the positive P-TEFb alleviates DSIF/NELF inhibition by phosphorylation of the CTD. It has been suggested that P-TEFb phosphorylation of the RNAP II CTD might promote transcription elongation by preventing interaction of DSIF/NELF with RNAP II (19).

The emerging overall picture of the transcription cycle proposes that the phosphorylation state of the CTD and the association of RNA processing factors are dynamic during elongation: different modified forms predominate at different stages of transcription.

While several kinase are putative candidates of RNAP II phosphorylation changes during the transcription cycle (4–7), FCP1 protein is the only CTD phosphatase identified thus far (20–24). It has been demonstrated that in vitro FCP1 functions as a positive elongation factor dephosphorylating the CTD and allowing efficient incorporation of RNAP II into the transcription initiation complex (24). Clearly, understanding the molecular function of FCP1 in recycling RNAP II during different steps of the transcription cycle is pivotal to gain a clear picture of the RNPA II CTD cycle and gene expression.

To explore the function of FCP1 protein we have examined the basic biological properties of FCP1 and dissection of the protein has led to the definition of significant domains of the protein involved in nuclear localization and transcription function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

GAL4 derivatives. The pSG424 vector was used as backbone vector to obtain the GAL4–FCP1 constructs. An EcoRV–SpeI insert from BSK4.1FCP1 (kindly provided by Dr Reinberg) containing the full-length FCP1 cDNA (24) was inserted into the SmaI site of pSG424 via blunt ligation. From this construct, GAL4–FCP1(1–833) was obtained by deletion of a XbaI fragment containing the sequences encoding the C-terminal region of FCP1 protein. GAL4–FCP1(120–961) was constructed by inserting a BspHI–EcoRI fragment from BSK4.1 into the SmaI site of pSG424. GAL4–FCP1(1–428) was obtained by deletion of the BamHI fragment containing sequences from amino acid 428 to 961. To obtain GAL4–FCP1(428–961) the KpnI insert from GFP–FCP1(428–961) (see below) was inserted into the SmaI site of pSG424. From this construct, GAL4–FCP1(428–833) was obtained by deletion of the XbaI fragment encoding the C-terminus of the protein. GAL4–FCP1(833–961) was obtained by inserting the XhoI–EcoRI fragment from GFP–FCP1(833–961) (see below) into the SmaI site of pSG424. The GAL4–RAP74 construct was generated by subcloning a NcoI–XhoI fragment containing the RAP74 coding region from the pET-23dRAP74 vector (25) into the pSG424 vector via blunt ligation. GAL4–Fin13 was obtained by subcloning the Fin13 coding region from the pRKS-Fin13 vector (26) into pSG424.

GFP derivatives. the pEGFP plasmids (Clontech) were used as backbone vectors for all GFP constructs. GFP–FCP1wt was constructed by inserting the EcoRI fragment from GAL4-FCP1 into the EcoRI site of pEGFP-C1. From this construct GFP–FCP1(1–833) was generated by deletion of the Acc651–XbaI fragment containing sequences encoding the C-terminus region. GFP–FCP1(428–833) was constructed by subcloning the BamHI fragment (sequence encoding amino acids 428–833) from GFP–FCP1(1–833) into the pEGFP-C1 vector. A BamHI fragment from GFP–FCP1wt containing sequence encoding amino acids 428–961 was subcloned into the BamHI site of the pGFPC1 vector. GFP–FCP1(833–961) was generated by subcloning a PCR product encoding the corresponding amino acids into pEGFP-C1.

FLAG derivatives. The pCMV-FLAG-FCP1 construct was obtained by inserting the SalI insert from pBSK4.1 into the SalI site of the pCMV-Tag2C vector (Stratagene). pCMV-FLAG-FCP1(1–833) was obtained by inserting an EcoRI–XbaI fragment from GAL4–FCP1(1–833) into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of the pCMV-Tag2A vector. Finally, pCMV-FLAG-FCP1(833–961) was constructed by subcloning a PCR product encoding the corresponding amino acids into the pCMV-Tag vectors. All constructs were verified by sequencing. A complete description of each plasmid construction used in this study is available on request.

Cell culture and transfections

293 and Cos cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient DNA transfections were performed as described (27–29), with LipofectAMINE reagent (Gibco BRL) in 2 cm multiwell dishes, using 100 ng of reporter DNA along with 500 ng of each activator as indicated in the text. Twenty nanograms of Renilla luciferase expression plasmid (pRL-CMV; Promega) were co-transfected for normalization of transfections efficiencies. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and extracts were assayed for luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay (Promega).

Co-immunoprecipitation

To prepare mammalian cell lysates after transfection of FLAG–FCP1 derivatives, 293 cells were resuspended in BC100 buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO4, 5 mM MgCl2). For co-immunoprecipitation analysis, the appropriate amount of lysate was incubated overnight with agarose-conjugated M2 anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma). The beads were then washed five times with BC100 without MgCl2. Finally, the beads were boiled for 5 min in SDS loading buffer and the supernatant was fractionated by electrophoresis. RAP74 protein was detected by western blotting of FLAG-immunoprecipitated lysates using a mixture of two commercially available antisera (C-18 and N-16; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

GFP analysis

Cos cells were grown on coverslips and 1 µg of GFP-expressing plasmid DNA was transfected using LipofectAMINE reagent. After 36 h, the transfected cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and washed in PBS, followed by DAPI-mediated nuclear staining. Cells were then mounted on slides and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Images were captured using a cooled charge-coupled device and analyzed with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging).

RESULTS

Artificial recruitment of FCP1 activates transcription

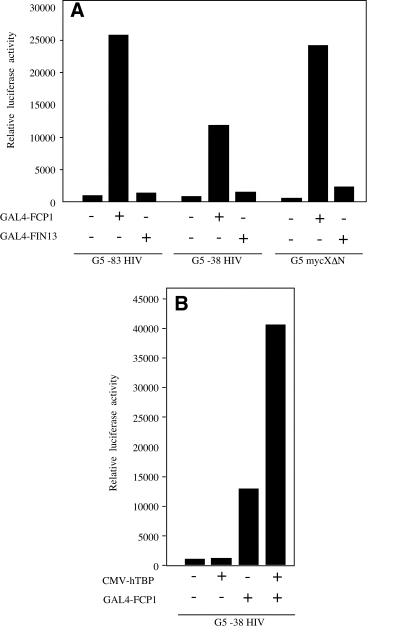

To investigate the proposed role of FCP1 protein in RNAP II transcription in vivo we analyzed the functional consequences of ectopic expression of FCP1 in transient transfections. We found that FCP1 overexpression does not significantly affect transcription driven by various RNAP II promoters such as the HIV-1 LTR, SV40 and c-myc (data not shown). Clearly, the lack of promoter specificity of FCP1 poses a severe limitation to functional studies of this factor in the regulation of transcription. To examine the role of FCP1 in transcription in a promoter-specific manner, we fused the FCP1 coding region to a sequence-specific DNA-binding domain (GAL4 DBD) and tested the ability of the fusion protein to modulate transcription of promoters containing appropriate GAL4 DNA-binding sequences. To evaluate the specificity of FCP1 on transcription we also examined the functional consequences of the nuclear phosphatase FIN13 (27). Both GAL4–FCP1 and GAL4–FIN13 were analyzed for ability to activate transcription driven by the G5–83HIV, G5–38HIV and G5–mycXΔN promoters, all bearing five GAL4 DNA-binding sites (28). As shown in Figure 1A, artificial recruitment of the FCP1 protein strongly activates transcription independently of the promoter context. Conversely, the GAL4–FIN13 fusion protein did not significantly affect transcription from any of the promoters tested. The finding that GAL4–FCP1 is able to activate, albeit to a minor extent, the minimal HIV-1 promoter (G5–38HIV) containing only the TATA box element, suggests that GAL4–FCP1 activates transcription independently of the presence of a canonical upstream transactivator.

Figure 1.

(A) Artificial recruitment of FCP1 protein to promoter template effectively activates transcription. Transfections of 293 cells were carried out using 100 ng of the indicated reporters together with 500 ng of GAL4–FCP1 or GAL4–FIN13 expression vectors as indicated. Each histogram bar represents the mean of at least three independent transfections made in duplicate. (B) Synergy between hTBP and FCP1 recruited to promoter DNA. The G5–38HIV reporter (100 ng) was transfected into 293 together with the indicated effectors (500 ng). In both panels, data are presented as luciferase activity relative to the sample without effector after normalization.

We and others have previously demonstrated that in vivo recruitment of TBP to a TATA box-containing promoter is a limiting step for transcription activation in mammalian cells and enforced expression of hTBP activates transcription of simple TATA-containing promoters (30–33). We reasoned that ectopic overexpression of two transcription factors that function at different steps during the transcription cycle should result in a synergistic effect. Thus, we tested whether synergistic activation of the G5–38HIV reporter could be seen when ectopic hTBP protein was co-expressed along with GAL4–FCP1 fusion protein. As shown in Figure 1B, a robust synergistic effect was found when both hTBP and GAL4–FCP1 were co-expressed. These findings strongly suggest that the observed synergy is likely due to the concerted action of different stimulatory factors affecting different rate-limiting steps in transcription. Thus, GAL4–FCP1 seems to act at a step different from hTBP recruitment. Because it was shown that FCP1 is a stochiometric component of the human RNAP II holoenzyme complex (23), a plausible rationale for GAL4–FCP1-mediated activation might involve recruitment of the RNAP II holoenzyme.

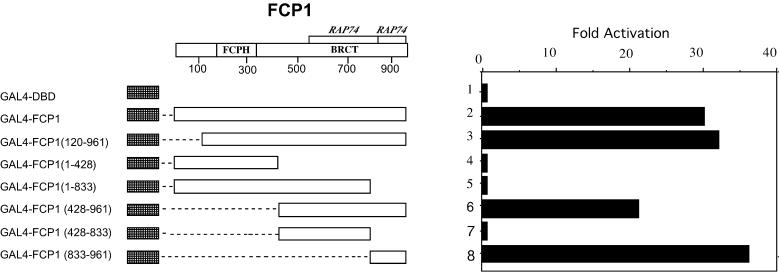

Sequences responsible for FCP1-mediated transactivation

To delineate the regions of human FCP1 that are functionally responsible for transcription activation in vivo a number of deletion mutants of GAL4–FCP1 were constructed and tested in transient transfections. As shown in Figure 2, we found that GAL4–FCP1(120–961) strongly activates transcription at levels indistinguishable from the full-length protein. FCP1(120–961) is identical to the previously isolated FCP1a (22,23) and in vitro results demonstrated that the 120–961 protein has a compromised phosphatase activity (24). In contrast, the GAL4–FCP1(1–428) fusion is ineffective in stimulating transcription while GAL4–FCP1(428–961) activates transcription at a level comparable to the GAL4–FCP1wt construct. Thus, the region from amino acid 1 to 120, which is required for in vitro CTD phosphatase activity, is dispensable for transcription activity as assessed in this type of assay, while the C-terminal region of the protein (amino acids 428–961) retains the ability to activate transcription. The FCP1 sequence downstream of amino acid 428 contains the interacting region for binding to RAP74 protein (22,23), the major subunit of the TFIIF factor. As shown in Figure 2, we found that neither GAL4–FCP1(428–833) nor GAL4–FCP1(1–833) activates transcription. In contrast, the GAL4–FCP1(833–961) fusion protein activates transcription at the same level as GAL4–FCP1wt. Western blot analysis of the transfected cells demonstrated that the various GAL4 fusions were expressed at comparable levels (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Identification of FCP1 domains critical for activation. A schematic representation of FCP1 protein and the GAL4–FCP1 fusion constructs is presented on the left. G5–83HIV reporter (100 ng) was co-transfected into 293 cells with the indicated expression vectors (500 ng). Data are presented as fold activation relative to the sample without effector after normalization. Each histogram bar represents the mean of at least three independent transfections.

These results define the sequences responsible for FCP1-mediated transactivation between amino acids 833 and 961 of FCP1 protein and the same region is also required and sufficient for binding to RAP74 (23; see below). Furthermore, FCP1 contains a BRCT domain (34–36) which has been shown to be important for proper function of this protein in yeast (37). It has been demonstrated that the BRCT domain of BRCA1 and some other proteins belonging to the BRCT family (38,39) are capable of stimulating transcription from a GAL4-responsive promoter when tethered via the GAL4 DBD (39). However, our results exclude the possibility that the FCP1 BRCT domain (amino acids 619–713) can function as a transactivation domain when artificially recruited on a GAL4-responsive promoter.

Collectively, our data demonstrate that the short region at the C-terminus of FCP1 is necessary and sufficient for transcription activation and that neither the N-terminus region encompassing the conserved phosphatase motif nor the BRCT domain are required for activation, at least in this in vivo transcriptional assay.

Interaction between FCP1 and RAP74

The FCP1 protein was originally isolated as a RAP74-interacting protein in a yeast two-hybrid screening. RAP74 is the major subunit of the TFIIF general factor and it has been shown that RAP74 and FCP1 are both components of the mammalian holoenzyme (23). This raised the possibility that the transcriptional activation observed on artificial recruitment of FCP1 protein could be related to recruitment on the targeted promoter of RAP74 and/or other components of the mammalian holoenzyme.

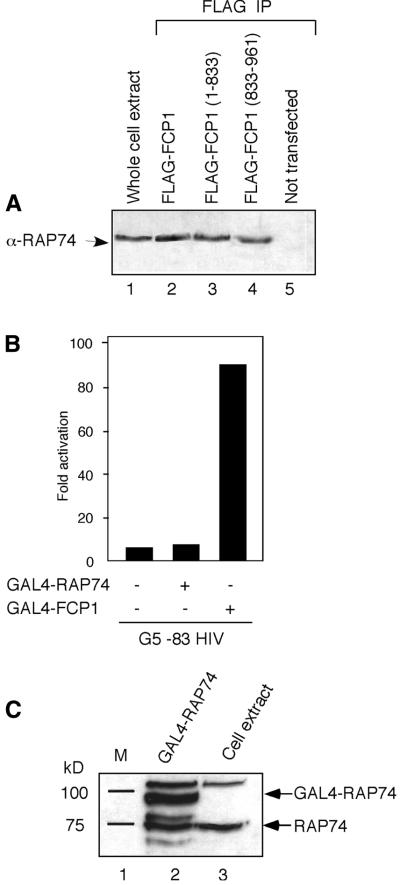

To analyze the interaction between FCP1 and RAP74 we carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments using exogenous FLAG-tagged FCP1 proteins. 293 cells were transfected with pCMVFLAG-FCP1wt, pCMVFLAG-FCP1(833–961) or pCMVFLAG-FCP1(1–833) vector. Protein extracts from transiently transfected cells were immunoprecipitated with a FLAG antibody and tested for RAP74 co-immunoprecipitation by western blotting using a mixture of RAP74 N-terminal and C-terminal antibodies. As reported in Figure 3A (lane 2), FCP1wt protein co-immunoprecipitates endogenous RAP74. Interestingly, we found that the FCP1(833–961) C-terminal tail region binds RAP74 protein in vivo with an efficiency indistinguishable from that observed using FCP1wt protein. In contrast, we found that FCP1(1–833) protein, lacking the C-terminal tail, showed a strongly compromised ability to bind RAP74 (Fig. 3A, lane 3; note the difference in the amounts of protein loaded on the gel). These results extend the previous findings showing that the FCP1 C-terminal region from amino acid 880 to 962 interacts with RAP74 in the yeast two-hybrid assay, demonstrating that the same previously defined region is also important for binding to RAP74 in human cells. Moreover, our results revealed a good correlation between the ability of FCP1 to activate transcription when brought into the vicinity of a promoter and its ability to bind to RAP74.

Figure 3.

Interactions between FCP1 and RAP74. (A) FCP1-containing complexes from cells expressing FLAG–FCP1wt, FLAG–FCP1(1–833) or FLAG–FCP1(833–961) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with agarose-conjugated M2 anti-FLAG antibody and analyzed for the presence of RAP74 by western blotting. Lane 1, volume corresponding to 20% of the input was loaded on the gel; lane 3, 5-fold more cell extract was immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody and loaded on the gel to obtain a similar intensity of signal. (B) Artificial recruitment of RAP74 protein to promoter template does not activate transcription. G5–83HIV reporter (100 ng) was co-transfected with GAL4–RAP74 or GAL4–FCP1 expression vectors (500 ng) as indicated. Data are presented as fold activation relative to the sample without effector after normalization. Each histogram bar represents the mean of at least three independent transfections. (C) Western blot of untransfected and GAL4–RAP74 293 transfected cells with RAP74 antibody displays the relative level of expression of GAL4–RAP74 compared to the endogenous RAP74 protein.

To further address the role of RAP74 in GAL4 fusion transcription, we fused RAP74 protein to the GAL4 DBD and tested the ability of GAL4–RAP74 fusion protein to modulate transcription. As shown in Figure 3B, while GAL4–FCP1 induces strong activation of the reporter vector, artificial recruitment of RAP74 protein does not activate transcription. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the GAL4–RAP74 fusion is efficiently expressed as compared to endogenous RAP74 protein (Fig. 3C).

These data demonstrate that artificial recruitment of FCP1 but not of RAP74 is sufficient to activate transcription and that the activity of DNA-bound FCP1 is mediated at least in part by its interaction with RAP74.

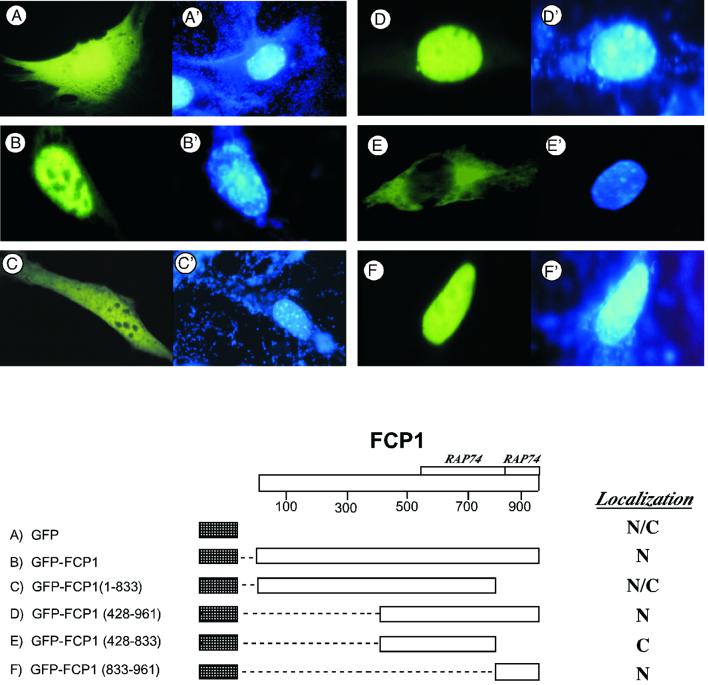

The C-terminal tail of FCP1 is required for nuclear localization

The results obtained in the previous section define the 128 amino acids at the C-terminus of the FCP1 protein as the region necessary and sufficient to confer the potential to strongly activate transcription when tethered to a targeted promoter. FCP1 is a nuclear protein (40) and computer-assisted analysis of the FCP1 protein sequence indicates the presence of three putative NLS at positions 79–85, 829–835 and 876–879, respectively. To verify if the NLS predicted by computer analysis were able to confer nuclear localization to FCP1 protein we constructed a panel of GFP–FCP1 fusion proteins as schematically shown in Figure 4. The GFP constructs were transfected into Cos cells and a representative example of our analysis is shown in Figure 4. Full-length FCP1 was exclusively localized to the nucleus. The C-terminus deletion FCP1(1–833) showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence, indicating the absence of an efficient nuclear localization signal. Thus, the region from amino acid 833 to 961 contains a sequence required for the exclusive nuclear accumulation of FCP1. We confirmed this result by using deletion constructs from the N-terminus. While FCP1(428–833) accumulates predominantly in the cytoplasm, FCP1(428–961) localized exclusively to the nucleus. Finally, we determined that the C-terminal region from amino acid 833 to 961 was sufficient to confer nuclear localization to the GFP fusion. The results shown in Figure 4 clearly demonstrate the presence of a functional NLS at the C-terminus of FCP1 between amino acids 833 and 961, as demonstrated by this domain being necessary and sufficient to confer nuclear localization when fused to the unrelated ubiquitous protein GFP.

Figure 4.

Nuclear localization of FCP1. Cos cells were transfected with the GFP fusion expression vectors encoding the indicated region of FCP1. (Top) Fluorescence microscopy images of GFP-positive cells from each transfection along with nuclear DAPI staining. (Bottom) Schematic representation of the GFP fusion constructs with their respective subcellular localization indicated as (N) nuclear, (C) cytoplasmic or (N/C) nuclear and cytoplasmic.

DISCUSSION

We here present evidence that targeted recruitment of FCP1 phosphatase to a promoter template strongly stimulates transcription and a short RAP74-interacting region in the C-terminal tail is required and sufficient for activity. The same C-terminus region is also required to direct FCP1 to the nucleus.

The primary sequence of FCP1 contains a motif denoted FCPH, common to a family of phosphatases acting on phosphate esters, that is within residues conserved among different putative CTD phosphatases. It has been shown that FCP1 in association with RNAP II reconstitutes a highly specific CTD phosphatase activity in vitro and that the FCPH motif is required for this activity (24). In vitro transcription studies have shown that the FCP1 CTD phosphatase allows recycling of RNAP II and the N-terminal domain of FCP1 is necessary for catalytic activity. Interestingly, in vitro stimulation of transcription elongation by FCP1 is independent of its catalytic activity (24). We found that the transcription activity of FCP1 protein when fused to GAL4 is independent of the presence of the N-terminal phosphatase domain. Thus, it appears that FCP1 can positively influence transcription both in vitro and in vivo in a manner that does not involve the presence of the FCPH domain. FCP1 contains a BRCT domain, found in a large family of proteins involved in cell cycle-related processes (34,35). Despite the sequence homology and functional proximity shared by several BRCT-containing proteins, it is not clear whether different BRCT domains confer a common biological activity. The BRCT region of BRCA1 and a few other BRCT proteins have been shown to activate transcription when targeted to an artificial promoter (39). However, we found that the BRCT domain is dispensable for ability of DNA-bound FCP1 to activate transcription.

In accord with the results reported here, it was recently reported that yFcp1 fused to a LexA DNA-binding domain activates transcription in yeast (37). Thus, it appears that in both yeast and mammalian cells artificial recruitment of FCP1 suffices to activate transcription in the absence of upstream activators. Most notably, in both yeast and mammalian cells the RAP74-interacting C-terminal domain is required and sufficient for activity of DNA-bound FCP1. Interestingly, determination of the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of RAP74 has recently been reported and it has been proposed that the predicted amphipathic α-helix structure at the acidic C-terminus of FCP1 might be responsible for binding to the concave hydrophobic/basic feature on the surface of the C-terminal domain of RAP74 (41). However, we found that direct recruitment of RAP74 to a promoter template through GAL4 DNA-binding sites is insufficient to activate transcription. In fact, we found that FCP1, but not RAP74, activates transcription by artificial recruitment. In addition to interacting with RAP74, it has recently been shown that yFcp1 also interacts with TFIIB. Although here we have not addressed the putative interactions between human FCP1 and TFIIB proteins, in accord with previous results we found that a GAL4–TFIIB fusion fails to activate transcription (33; data not shown).

The data presented demonstrate that FCP1 is able to activate core promoters in the absence of upstream activators and co-expression with hTBP results in a strong synergistic activation of transcription. Thus, GAL4–FCP1 seems to act at a step different from hTBP recruitment. These findings strongly suggest that the synergy is likely due to the concerted action of different stimulatory factors affecting different rate-limiting steps in transcription. Because it was shown that FCP1 is a stochiometric component of the human RNAP II holoenzyme complex (23), a plausible rationale for the GAL4–FCP1-mediated activation might involve recruitment of the RNAP II holoenzyme.

Collectively, our findings along with a recent study in yeast (37) demonstrate that FCP1 phosphatase has a specific ability to activate transcription when artificially recruited to a promoter template and that such function is conserved between yeast and mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Burton and Basilico for reagents and Drs R. Dalla Favera and W. Gu for valuable comments and help. This work was supported by grants from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC), Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Programma Nazionale di Ricerca AIDS (grant 40A.0.57) and MURST (COFIN).

References

- 1.Dahmus M.E. (1996) Reversible phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 19009–19012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zawel L., Lu,H., Cisek,L.J., Corden,J.L. and Reinberg,D. (1993) The cycling of RNA polymerase II during transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol., 58, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahmus M.E. (1994) The role of multisite phosphorylation in the regulation of RNA polymerase II activity. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 48, 143–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conaway J., Shilatifard,A., Dvir,A. and Conaway,R.C. (2000) Control of elongation by RNA polymerase II. Trends Cell Biol., 25, 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reines D., Conaway,R.C. and Conaway,J.W. (1999) Mechanism and regulation of transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 342–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uptain S.M., Kane,C.M. and Chamberlin,M.J. (1997) Basic mechanisms of transcript elongation and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 66, 117–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komarnitsky P., Cho,E.-J. and Buratowski,S. (2000) Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev., 14, 2452–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho E.J., Takagi,C.R., Moore,C.R. and Buratowski,S. (1997) mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev., 11, 3319–3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose Y. and Manley,J.L. (1998) RNA polymerase II is an essential mRNA polyadenylation factor. Nature, 395, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCracken S., Fong,N., Yankulov,K., Ballantyne,S., Pan,G., Grenblatt,J., Patterson,S.D., Wickens,M. and Bentley,D.L. (1997) The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature, 385, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCracken S., Fong,N., Rosonina,E., Yankulov,K., Brothers,G., Siderovki,D., Hessel,A., Foster,S., Shuman,S. and Bentley,D.L. (1997) 5′-Capping enzymes are targeted to pre-mRNA by binding to phosphorylated carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev., 11, 3306–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall N.F. and Price,D.H. (1995) Purification of P-TEFb, a transcription factor required for the transition into productive elongation. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 12335–12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall N.F., Peng,J., Xie,Z. and Price,D.H. (1996) Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 27176–27183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y., Pe’ery,T., Peng,J., Ramanathan,Y., Marshall,N., Marshall,T., Amendt,B., Mathews,M.B. and Price,D.H. (1997) Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for HIV-1 Tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev., 11, 2622–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price D.H. (2000) P-TEFb, a cyclin-dependent kinase controlling elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 2629–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi Y., Takagi,T., Wada,T., Yano,K., Furuya,A., Sugimoto,S., Hasegawa,J. and Handa,H. (1999) NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell, 97, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wada T., Takagi,T., Yamaguchi,Y., Watanabe,D. and Handa,H. (1998) Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J., 17, 7395–7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada T., Takagi,T., Yamaguchi,Y., Ferdous,A., Imai,T., Hirose,S., Sugimoto,S., Yano,K., Hartzog,G.A., Winston,F., Buratowski,S. and Handa,H. (1998) DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev., 12, 343–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada T., Orphanides,G., Hasegawa,J., Kim,D.K., Shima,D., Yamaguchi,Y., Fukuda,A., Hisatake,K., Oh,S., Reinberg,D. and Handa,H. (2000) FACT relieves DSIF/NELF-mediated inhibition of transcriptional elongation and reveals functional differences between P-TEFb and TFIIH. Mol. Cell, 5, 1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers R.S. and Dahmus,M.E. (1994) Purification and characterization of a phosphatase from HeLa cells which dephosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 26243–26248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers R.S. and Kane,C.M. (1996) Purification and characterization of an RNA polymerase II phosphatase from yeast. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 24498–24504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Archambault J., Chambers,R.S., Kobor,M.S., Ho,Y., Cartier,M., Bolotin,D., Andrews,B., Kane,C.M. and Greenblatt,J. (1997) An essential component of a C-terminal domain phosphatase that interacts with transcription factor IIF in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 14300–14305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archambault J., Pan,G., Dahmus,G.K., Cartier,M., Marshall,N., Zhang,S., Dahmus,M.E. and Greenblatt,J. (1998) FCP1, the RAP74-interacting subunit of a human protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase IIO. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 27593–27601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho H., Kim,T.K., Mancebo,H., Lane,W.S., Flores,O. and Reinberg,D. (1999) A protein phosphatase functions to recycle RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev., 13, 1540–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B.Q. and Burton,Z.F. (1995) Functional domains of human RAP74 including a masked polymerase binding site. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 27035–27044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guthridge M.A., Bellosta,P., Tavoloni,N. and Basilico,C. (1997) FIN13, a novel growth factor-inducible serine-threonine phosphatase which can inhibit cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5485–5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majello B., Napolitano,G., Giordano,A. and Lania,L. (1999) Transcriptional regulation by targeted recruitment of cyclin-dependent CDK9 kinase in vivo. Oncogene, 18, 4598–4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napolitano G., Licciardo,P., Gallo,P., Majello,B., Giordano,A. and Lania,L. (1999) The CDK9-associated Cyclins T1 and T2 exert opposite effects on HIV-1 Tat activity. AIDS, 13, 1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Licciardo P., Napolitano,G., Majello,B. and Lania,L. (2001) Inhibition of Tat transactivation by the RNA polymerase II CTD-phosphatase FCP1. AIDS, 15, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majello B., Napolitano,G., De Luca,P. and Lania,L. (1998) Recruitment of human TBP selectively activates RNA polymerase II TATA-dependent promoters. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 16509–16516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He S. and Weintraub,S.J. (1998) Stepwise recruitment of components of the preinitiation complex by upstream activators in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 2876–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nevado J., Gaudreau,L., Adam,M. and Ptashne,M. (1999) Transcriptional activation by artificial recruitment in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 2674–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorris D.R. and Struhl,K. (2000) Artificial recruitment of TFIID, but not RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, activates transcription in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 4350–4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bork P., Hofmann,K., Bucher,P., Neuwald,S.F., Altschul,S.F. and Koonin,E.V. (1997) A superfamily of conserved domains in DNA damage-responsive cell cycle checkpoint proteins. FASEB J., 11, 68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X., Morera,S., Bates,P.A., Whitehead,P.C., Coffer,A.I., Hainbucher,K., Nash,R.A., Sternberg,M.J., Lindahl,T. and Freemont,P.S. (1988) Structure of an XRCC1 BRCT domain: a new protein–protein interaction module. EMBO J., 17, 6404–6411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobor M.S., Archambault,J., Lester,W., Holstege,F.C., Gileadi,O., Jansma,D.B., Jennings,E.G., Kouyoumdjian,F., Davidson,A.R., Young,R.A. and Greenblatt,J. (1999) An unusual eukaryotic protein phosphatase required for transcription by RNA polymerase II and CTD dephosphorylation in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell, 4, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobor M.S., Simon,L.D., Omichinski,J., Zhong,G., Archambault,J. and Greenblatt,J. (2000) A motif shared by TFIIF and TFIIB mediates their interaction with the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain phosphatase Fcp1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7438–7449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman M.S. and Verma,I.M. (1996) Transcriptional activation by BRCA1. Nature, 382, 678–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyake T., Hu,Y.F., Yu,D.S. and Li,R. (2000) A functional comparison of BRCA1 C-terminal domains in transcription activation and chromatin remodeling. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 40169–40173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubois M.F., Marshall,N.F., Nguyen,V.T., Dahmus,G.K., Bonnet,F., Dahmus,M.E. and Bensaude,O. (1999) Heat shock of HeLa cells inactivates a nuclear protein phosphatase specific for dephosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 1338–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamada, K., De Angelis,J., Roeder,R.G. and Burley,S.K. (2001) Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of the RAP74 subunit of human transcription factor IIF. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 3115–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]