Abstract

Structural biology, like many other areas of modern science, produces an enormous amount of primary, derived, and “meta” data with a high demand on data storage and manipulations. Primary data comes from various steps of sample preparation, diffraction experiments, and functional studies. These data are not only used to obtain tangible results, like macromolecular structural models, but also to enrich and guide our analysis and interpretation of existing biomedical studies. Herein we define several categories of data resources, (a) Archives, (b) Repositories, (c) “Databases” and (d) Advanced Information Systems, that can accommodate primary, derived, or reference data. Data resources may be used either as web portals or internally by structural biology software. To be useful, each resource must be maintained, curated, and be integrated with other resources. Ideally, the system of interconnected resources should evolve toward comprehensive “hubs” or Advanced Information Systems. Such systems, encompassing the PDB and UniProt, are indispensable not only for structural biology, but for many related fields of science. The categories of data resources described herein are applicable well beyond our usual scientific endeavors.

Keywords: Database, repository, data resource, structural biology, archive, metadata, information system

1 Introduction

Physics was the driving force of science in the first half of the 20th century, followed by a shift of emphasis toward the biomedical sciences. We predict that the 21st century will be dominated by information technology and that the analysis of data will be even more important than the generation of new data. Massive amounts of data create significant challenges not only for data storage but also for organization, accessibility, data mining, and analysis. As discussed elsewhere in this book, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the crown jewel of structural biology and a well-known example of a data resource used widely in biomedical sciences [1]. Besides the PDB, there are a large number of repositories and databases used in structural biology, chemistry, life sciences, and big pharma, where they are crucial in the drug discovery process.

Modern research produces an enormous amount of primary data. Within structural biology, the primary data comes from the various steps of protein production and crystallization, from the X-ray and neutron diffraction experiments, cryo-EM, or from functional studies aimed at characterizing and/or verifying structure-function relationships. Technological advances and increased computational capabilities permit the collection of terabytes or even petabytes of primary experimental data in a very short time. For example, the Eiger 4M detector at station 30A-3 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) [2] can produce 750 images per second. This would result in 64.8 million data frames per day and assuming 2000 hour/year of ESRF operation (for further calculations, we assume that half of the time is used for sample changing, alignment, etc.), 2.7 billion data frames, totaling around 20 petabytes per year when operated at peak efficiency. Assuming conservatively that three data sets containing 1000 images each are sufficient to determine and deposit a macromolecular crystal structure, the output of station 30A-3 would be 270 times higher than the output of all 150 synchrotron stations located at roughly 40 synchrotrons around the world. The disparity between theoretical data production rate and structure determination rate reflects our limited ability to use information technology to select diffraction-quality crystals prior to diffraction experiments, to find and remove other bottlenecks, and to convert mountains of data into useful information. Structural biology is not unique in this respect. In modern science, we have learned how to generate massive amounts of data; but unfortunately, creating scientific knowledge is a much harder task. Modern scientists quite often forget that “data is not information, information is not knowledge, knowledge is not understanding, understanding is not wisdom [3].”

Effective transformation of results into information requires that data be associated with metadata – data about data – defining what the underlying data represents, what format it is in, who collected it etc. Metadata is crucial for organizing data into “databases.” In a narrow technical sense, a database is any organized set of data, a raw material from which information can be “mined”. The term “database” is also widely used to describe many data resources, but in our opinion, the term database should be reserved for resources that include some elements of an information system (IS), namely tools for extracting information from data that adhere to the basic paradigm: data-in, information-out. This is in contrast to the functionality of a data repository, which utilizes a data-in, data-out approach. In practice, the capabilities of information extraction tools of “database” resources available in structural biology are very diverse. Arguably, the Holy Grail – a full-fledged “information system” – remains to be implemented yet.

Data resources vary widely with respect to their design, complexity, accessibility, etc. Although data resources of all kinds can be useful, the impact of a resource is partially dependent on its sophistication/complexity and scope. For the purpose of this chapter, we define several specialized categories of data resources, such as (a) Archives, (b) Repositories, (c) “Databases” and (d) Advanced Information Systems1. Depending on the stage and scale of the project, each of these four categories has its advantages and disadvantages, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typical characteristics for four specialized categories of data resources

| Archives | Repositories | “Databases” | Advanced Information Systems (AIS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Complexity | Low | Medium | High | High |

|

| ||||

| Content | “Raw” (deposited) data with little or no metadata | Probably include some metadata | Extensively curated metadata | Extensively curated metadata, integrated with external resources |

|

| ||||

| Searches and Retrieval | Data not necessarily indexed, searching cumbersome | Data is indexed, facilitating searches | Search usually driven by a database (in a technical sense) | Efficient search and retrieval |

|

| ||||

| Data mining | Very difficult | Limited to basic statistics | Built-in data analysis and report generation tools. Precalculated result | Customizable tools for analysis of user data |

|

| ||||

| Data validation | No validation | Limited validation | Full validation | Full validation; Mechanism for moderated user’s corrections |

|

| ||||

| Data architecture | No organization; typically just a set of files | Partial organization (e.g. subfolders) | Data is structured and maybe distributed | Data is structured and maybe distributed |

|

| ||||

| Users/Audience | Usually limited to a single lab or institution | Collaborative/Public access | Single lab, Organization or Public | Organization or Public |

|

| ||||

| Cost | ||||

| Setup | Low | Medium - High | High | Very High |

| Storage | Low - Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Maintenance | Low | Medium - High | High - Very High | Very High |

| Annotation | N/A | Medium - High | High | Very High |

| Curation | N/A | Low - Medium | Medium - Very High | Very High |

Metadata is data that describes other data. Meta is a prefix that in most information technology usages means “an underlying definition or description.” Metadata summarizes basic information about data, which can make finding and working with particular instances of data easier.

2 Categories of Data Resources

Archives are the least sophisticated type of data resource in terms of complexity and are the most straightforward to implement. In the most simplistic terms, an archive is created when an experimenter collects experimental data on some sort of storage media. Data archives are usually not indexed and possess limited metadata. For that reason, they are usually easy to access and search by creators, but searching an archive created by somebody else can be a gargantuan task. Due to the low initial set-up cost, archives are usually the most feasible way to collect the first batch of primary data or to serve as a reference in computational studies. An electronic laboratory notebook (ELN) is a typical example of personalized archive for an experimenter, and a set of PDB files is a typical archive used during structural computations.

Archives that are actively used by multiple contributors tend to grow very fast and become difficult to manage, especially when data are more complex than anticipated by the archive creator. This is usually the stage at which the archive has to be converted into a repository. Repositories are characterized by the use of additional mechanisms (metadata) to index and annotate the primary data. Data in repositories may need to be validated in order to be presented in a more consistent manner and to facilitate searches by different contributors and users. A repository may either remain to be of small-scale with a minimal set of metadata on top of an archive or become very sophisticated with capabilities similar to a database. Repositories are the most prominent category that implies public accessibility, which may or may not be true for the other three categories. Repositories are usually less sophisticated than fully-fledged “databases”, but their role and impact cannot be underestimated. For example, the Protein Data Bank is a gigantic repository [4] that handles a wide array of complicated data and serves as a central reference of macromolecular structural data. The UniProt repository plays a similar role for known protein sequences and for that reason is a few orders of magnitude larger in terms of the number of records [5].

The third category of data resource, the “database”, is characterized by the paradigm of “data in, information out.” All data are structured, and there are mechanisms to enforce internal and sometimes external consistency. Well-designed databases use various validation tools to analyze all incoming data and ensure their consistency with external resources. This type of resource has pre-defined data mining tools available for casual users, as well as sophisticated tools to carry out custom analysis of the underlying data. An example of a pre-defined report is an automatically generated draft of the methods section of a scientific manuscript providing information about protein production and diffraction experiments [6]. The ability to add a materials/methods section of a manuscript with minimal or no intervention would serve as the ultimate confirmation of the accuracy and usefulness of the database. One feature that distinguishes a database from a repository is the ability to update the data it contains. The inability to change the data in a repository is not only due to technical limitations but mainly because the repository is not necessarily the owner of the data.

An Advanced Information Systems (AIS) will invariably have a “database” at its core, but will have more connections to other data resources, pulling together information from disparate sources to provide as complete a picture as possible. AIS will have sophisticated tools to allow users to analyze the data, and may include mechanisms to allow others to access the data in an automated fashion. Registered users may have the ability to update information in an AIS, and well-designed systems will have a mechanism to keep track of the changes.

It is also important to keep in mind that boundaries among these four categories are fluid and subjective. A data resource of one archetype may also possess characteristics of other data resource categories. For example, although the PDB exhibits prominent properties of a repository, it also has many properties of a database, such as the ability to perform advanced searches on many fields regarding the experimental details and subsequently combine the results of different queries. The PDB policy of “obsoleting” deposits, which requires the agreement of the deposit’s author, is one characteristic that arguably makes it more of a repository than a “database”. The degree of connectivity with other resources will distinguish AIS. It is also important to note that data resources can evolve into more sophisticated resources, or regress to more primitive forms when maintenance is no longer possible.

The storage and deployment of diffraction images is a typical example used to illustrate the usefulness of different categories of data resources in the life cycle of a project in structural biology. For example, the ftp server of CSGID [7] (http://www.csgid.org/pages/diffraction_images) was a simple data resource that fell in the “archive” category. This archive was very useful at collecting and preserving all the diffraction images collected by the CSGID and later SSGCID [8] projects. The CSGID ftp server was easy to set up and ready for use in a matter of days. Although it was essentially impossible to retrieve the data by means other than the target accession code, the CSGID ftp server was successfully used to share diffraction data between research groups and external users. There are other archives of diffraction images in other organizations. Virtually all synchrotron facilities have temporary “archives” of collected data that are wiped-out after a certain period of time. The http://ProteinDiffraction.org server in its current form is a mix of such a repository and “database”, yet the ultimate goal of this project is to transform it into an IS-Database that has every bit of information structurally organized and fully validated. The transformation of the CSGID ftp server into the http://ProteinDiffraction.org server is a good example of resource evolution without change of the data contained in it.

3 Structural Biology Data Resources

3.1 Primary Data Repositories

Despite the fact that many scientists treat the final structural models (both macromolecular and small molecular) as primary data, the models themselves are only interpretations of the experimental data and should be treated as derived data. In fact, only diffraction images (in crystallography), recorded spectra (in NMR), and unprocessed images (in electron microscopy) should be considered as “primary” data. A long-term, large-scale storage of diffraction images has recently become possible due to reduced cost of media and improved data access and storage technologies [9]; however, the cost associated with data management remained steady or even increased due to the complexity of modern crystallography experiments. The anticipated size of a repository has a direct influence on the technical aspects of the design and also on the maintenance of the resource. A resource that has 10 or 100 diffraction experiments will have different issues than a resource that can accommodate 100,000 or one million experiments. Maintaining the homogeneity of the data using automated systems becomes more difficult as the scale of a resource grows and the experimental complexity and resulting variability of data types increases.

The first large-scale public archives of macromolecular diffraction images were implemented independently by structural genomics consortia [7, 10]. Some synchrotron facilities have also created large scale archives, but only a very limited subset of data are publicly available. For example, the Store. Synchrotron [11] implemented at the Australian Synchrotron facility, based on the MyTardis system [12] that claims thousands of archived diffraction experiments makes only 35 of them publicly available. To ensure standardization of data and metadata, the IUCr established the Diffraction Data Deposition Working Group (DDDWG) [13]. Recently, two repositories that allow deposition of diffraction images of macromolecular structures emerged – proteindiffraction.org and SBGrid DB [14] that explore community needs and assess the technical capabilities and limitations. Proteindiffraction.org also aims to provide an information system that would allow better data dissemination.

3.2 Reference Repositories

Although structural models are derived data, they serve as a foundation for many further studies and are treated as primary reference data. The reference data resources are usually repositories augmented with database functionality to facilitate data searches. Analysis of a large group of data requires the use of auxiliary tools. The prime example of the data repository used in structural biology is the earlier version of the PDB [15]. This repository is covered in another chapter in this book in detail, but for clarity of presentation, we briefly discuss it also here. The PDB repository [4] has five access sites: the wwPDB site, three data centers (PDBe, PDBj and RCSB PDB), and an NMR specific component, the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB). While the wwPDB site allows data validation and deposition as well as archive download, the remaining sites have more database capabilities that allow for data dissemination. All three PDB data centers utilize the common mmCIF format [16] to store the same underlying structural data, however, the design, information content, and analysis tools of each site are different. The three data centers create different user experiences and illustrate the different ways for a repository to evolve into an Advanced Information System.

Repositories of small molecule structures are indispensable for macromolecular crystallography because they serve as reference resources for all ligands bound to the macromolecules. The most renowned resource of this kind is the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) – a database of organic and metal-organic molecules, which comes additionally with a comprehensive package of tools for data mining and data analysis [17]. An alternative is the Crystallography Open Database (COD) [18], which is an open-access archive of organic, inorganic, and metal-organic compounds and minerals. There are also several other, specialized databases available, such as ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [19] and CRYSTMET (metals, alloys and intermetallics) [20].

In addition to structural information, an enriched set of metadata about small molecules, chemical substances and their compounds – including but not limited to identity, chemical properties and biological activity – can be accessed using the resources forming PubChem [21] and ChEMBL [22]. Similarly, information about proteins can be accessed from the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) [5], while information about protein location, function and interactions can be accessed from Gene Ontology (GO) [23] or Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [24].

3.3 Derived Data Resources

The growing number of macromolecular structures in the PDB provides a solid foundation for and increases the scientific potential of derivative data resources that build upon the data from the PDB. These resources can be divided into three categories: classification/cataloguing, data presentation/analysis/processing, and data aggregation.

Typical examples of classification of the structural data present in the PDB are fold classification databases like CATH [25] and SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins) [26]. These databases aim to classify protein folds in terms of evolutionary relationships as well as structure and sequence similarity. The classifications provided by SCOP and CATH have become the de facto standards for describing the fold of a protein that is newly characterized in structural terms. The SCOP database is also a reference database for non-redundant folds and domains used by many structural bioinformatics tools.

SCOP is an interesting example illustrating the necessity of the long-term maintenance of widely adopted databases. The original SCOP classification was last updated in 2009. In 2012, some authors of the original SCOP developed a backwards compatible continuation called SCOPe [27], which is currently up-to-date with the PDB. In 2014, the laboratory which originally developed SCOP renovated the original SCOP classification system and called it SCOP2 [28]. As pointed out by the developers of SCOP2, the simple tree-like hierarchy used in SCOP was replaced by a network of nodes in SCOP2.

There are many other, specialized data resources that try to catalogue and classify a different structural aspect beyond fold classifications. For example, several resources for membrane proteins have been developed. One of the first publicly available membrane protein databases was the Protein Data Bank of Transmembrane Proteins (PDBTM; http://pdbtm.enzim.hu) maintained by the Hungarian Institute of Enzymology [29–31]. It continues to provide an up-to-date list of 3-D structures of transmembrane proteins based on the detection of transmembrane helices in the structure using the program TMDET [32]. As of April 2016, this resource contained 2771 PDB entries. MPStruc, the database of Membrane Proteins of Known 3-D structure [33], established by Stephen White’s group, not only identifies unique membrane protein structures (609 as of April 2016) but also provides the MPExplorer tool which can provide hydropathy plots based upon thermodynamic and biological principles, allowing examination of topological properties of membrane proteins (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/). The MemProtMD [34] has used the Coarse-Grained Self Assembly Molecular Dynamics simulations to compile the database of structures of over 2000 intrinsic membrane proteins inserted into simulated lipid bilayers. The “Membrane Protein Data Bank [35]” is still available on the Internet but has not been updated since 2011, also illustrating the problem of database maintenance.

An interesting example of classification of protein features is the KnotProt database [36], which runs a program detecting self-entanglements in protein chains in order to identify proteins whose 3-D structures form knots or slipknots. KnotProt currently contains nearly 1400 entries, and it also allows users to submit structural data to check if they correspond to a knotted structure. The KnotProt effectively replaced several previous databases that were still available, but not maintained. The lack of maintenance and curation may have created inconsistencies between resources, leaving users with ambiguous information.

Bioinformatics services are another type of structural biology resources that build upon the structures in the PDB. A prominent example is PDBsum [37]. This service applies different tools and resources in order to present at-a-glance overview of a protein structure. It includes analysis of structural attributes such as protein surfaces, cavities, and ligands, as well as interaction attributes such as the protein-protein, protein-DNA/RNA, and protein-small molecule interactions. The approach adapted by PDBsum is gradually being incorporated into the PDB access sites such as the RCSB, PDBe and PDBj.

Another well-established resource that supplements the PDB is the Uppsala Electron Density Server (EDS) [38]. In addition to the basic information about the deposit, EDS calculates the electron density maps from the deposited structure factors (if available) and provides the user with a straightforward way to check the real-space model correlation and to download and inspect electron density maps. The EDS is used internally by COOT [39, 40], PyMOL [41] and other programs to download ready-to-view electron density maps for inspection. As with many servers that reach the end of an initial funding period, this server is still available and running in an automatic mode, but it is no longer supported or developed, and there is no mechanism to correct errors, despite its widespread usefulness and appreciation [42].

Another type of structural bioinformatics resource provides data analysis/processing. An example of such data resource is PDB_REDO [43], which automatically re-refines the structures with available structure factors in the PDB using the latest versions of crystallographic tools, and makes the revised structures and re-refinement statistics available for download. The PDB_REDO partially implements the concept of the “living PDB.” [44]; however, fully automated re-refinement has a long way to go [45, 46]. Somewhat related data resources that provide pre-calculated results are the repositories of comparative models. The ProteinModelPortal [47] provides a gateway to several repositories of pre-calculated comparative models, such as ModBase [48] and SWISS-MODEL Repository [49]. Several databases provide pre-computed results useful for the analysis of the macromolecular structures deposited in the PDB. For example, PDBFlex [50] provides a database of pre-calculated structural alignments of different structures of the same protein and analyze them to explore the flexibility of protein structures. PDBePISA implements a repository of pre-calculated PISA results for all PDB deposits [51, 52]. These results may be used to analyze protein-protein interfaces and for prediction of energetically-favorable assemblies.

The Protein Structure Initiative Structural Biology Knowledge Base (PSI SBKB) [53], which was based on aggregating data from a number of resources created by the PSI programs, has become an important “added value” resource. By combining tools such as KB-Rank and KB-Role with searches through multiple resources, it allows users to identify connections between sequence, structure, annotation, and function. Unfortunately, due to the termination of the PSI, operation of the PSI SBKB is currently scheduled to end in July 2017.

Recently, the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative has started building a prototype of the “super-aggregator” DataMed, intended as a one-stop service providing an entry point to all biomedical and health-care related data resources (http://biocaddie.org). Currently, it has indexed a single structural biology resource – the PDB. However, as it also includes data repositories from other domains (e.g. sequence, gene expression, proteomics, clinical trials, and others), it already allows for identifying potential relationships among the PDB structures and datasets from these different domains [54].

4 Data Management in Structural Biology

From the onset of the high-throughput era, different laboratories recognized the need for efficient tools for tracking experimental protocols, parameters, personnel, reagents, remarks, and results. Different tools emerged to serve the particular needs of individual laboratories and their workflows. Apart from generic electronic lab notebooks (ELN) and generic laboratory information management systems (LIMS), several databases specializing in the handling of structural biology pipelines have been developed. The development was mainly motivated and supported by the structural genomics programs to accommodate the needs of laboratories, consortia, and shared user facilities such as synchrotrons, but was later demonstrated to be very productive as tailored LIMS to track experiments in collaborations and laboratories of any size. Examples of databases that are used by structural genomics are SESAME [55] and LabDB [6]. SESAME was initially developed as a database for tracking NMR experiments at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison [55] and was further enhanced to serve the needs of the Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics (CESG) [56]. LabDB, on the other hand, was initially developed as a LIMS for a single laboratory to track crystallization experiments and to serve as a companion database to HKL-3000 [57], which allowed for a tight integration of experimental and computational parts into a unified crystallographic pipeline. LabDB was later adopted as a central LIMS by several structural genomics centers and was enhanced with data harvesting and data analysis capabilities for different experiments. ISPyB is yet another example of a database used to track experiments. It was designed for the ESRF synchrotron to allow users to track their samples and experiments and is now an integral part of the data collection systems at the ESRF and Diamond synchrotrons, and is crucial for further automation.

4.1 Reporting/Data Analysis

The actions and results of structural biology and data mining programs during data processing and structure refinement can also be viewed as data resources for the purpose of keeping track of history, reporting, and data analysis. Simple project management tools exist both in the CCP4 Interface and PHENIX. Using a text-file based database, both of these project management tools allow tracking jobs, associated files, and runtime parameters. In addition to the text file, other metadata about the history of data harvesting and processing are stored alongside structure factors in MTZ files. Simpler job handling panels that utilize an underlying databases are also available in many web servers, such as Robetta [58], Molprobity [59], TLSMD [60] or Surface Entropy Reduction prediction (SERp) server [61].

On the other hand, HKL-3000 runs a full relational database backend (HKLDB) and stores the complete histories of diffraction experiments, data processing, and structure determination. HKLDB seamlessly integrates with LabDB to provide an experimental history of the crystal. The approach of running a full relational database in this scenario also allows for effective project management and collaboration within and between labs and institutions, as well as large-scale data analysis of different approaches and results. The HKLDB/LabDB system has also provided essential data resources to support the statistics and reporting tools used in several structural genomics web portals, such as the CSGID database.

5 Data Resources Used Internally by Structural Biology Software

Many crystallographic software packages use one or several data resources to perform their tasks. These data collections may include external, unprocessed data sets such as sequence databases, collections of structures, or data prepared for specific application. The data resources used in different applications can be of various sizes, have different sophistication levels, and be characterized by different curation levels. Very often, the fact that the software relies on these resources is not obvious, as the user faces only the interface, and the usage of some kind of a database either as a data source or data storage is an internal implementation detail. The quality and type of used data resources may significantly impact the outcome of the application; therefore, it is important to realize what types of data resources are used internally by specific applications. Here, we would like to highlight several notable, application-specific data resources that form the foundation of various tools used in structural biology.

One reason that an application or data resource may incorporate information from other data resources is to provide additional information that cannot be produced by the program itself or is computationally expensive to recreate. For example, the information content (resolution) of a macromolecular diffraction experiment is typically not sufficient to build a satisfactory model of a macromolecule without prior knowledge about protein geometry; thus, the majority of macromolecular structures are modeled and refined using “restrained refinement”. As the name implies, during such refinement atoms are not permitted to move freely but are restricted by various “rules”. There are several classes of restraints that are commonly used (covered in other chapters), but for the purpose of this chapter, we will focus on restraints (and their preparation) that are based on different data resources.

The most basic restraints that are used for the refinement of macromolecular structures are restraints that are applied to the monomer residues and small molecule residues. Programs that perform either reciprocal-space refinement, such as REFMAC [62], PHENIX [63] or SHELXL [64], or real-space refinement, e.g. COOT [40], use an archive of text files to store pre-generated definitions of monomers and some small molecules. Since this is the primary source of correct geometries for the refined residues, any inaccuracies in the restraint library would easily propagate to the refined structure and its interpretation [62]. While structural units of macromolecule monomers, such as amino acids and nucleic acid bases, are well defined due to abundant information, small-molecule ligands may have a much wider variation and may be represented by only a limited number of experimental data. Therefore, it was necessary to put a significant effort toward the development of software like LIBCHECK [65], PURY [66], eLBOW [67], and AceDRG [68]. Built on top of prior knowledge of bond lengths and bond and dihedral angles from small molecular crystallography databases such as CSD or COD and ab initio calculations, these data resources perform additional validation and generate custom definitions of the small molecule. Moreover, software such as PURY may also modify or augment the existing data resources to present a more consistent library of restraints for the refinement program.

With the rapid growth of the PDB, it became possible to develop new applications that efficiently leverage the knowledge gained from existing structures. The applications useful in macromolecular model building are usually supported by underlying data resources that are derived from the PDB. These underlying data resources are usually highly abstracted and curated with only relevant data extracted to serve the algorithm with a significant boost in quality, validity, or speed. For example, as the number of high resolution structures in the PDB increases, libraries of amino-acid side-chain rotamers evolve over time – leading to popular libraries like the backbone-independent library [69] or the backbone-dependent one [70]. Amino acid side-chain rotamers are commonly stored as a simple combination of the representative χ angles or actual atom coordinates and rotamer occurrence frequencies and are widely used in model-building and refining software including COOT, PHENIX, or ROSETTA. Sometimes for specific purposes, especially for exhaustive search as in Fitmunk [71] or Rapper [72], more complicated conformer libraries containing many curated conformations from representative structures are used. Additionally, some model building programs such as ARP/wARP [73], Buccaneer [74], and RESOLVE [75] use larger fragments of proteins to build the complete model.

Another way a data resource can be used by structural software is to serve as an internal reference of structures or structural features, such as those used for molecular replacement or model building. For example, BALBES [68] and MORDA [76] molecular replacement pipelines use a prepared database of PDB structures to search for a model suitable for molecular replacement and to carry out the structure determination – an approach that is extremely successful when the simple approach of using a manually selected model fails. Similarly PHASER [77] and AMoRe [78] allow users to create their own small archives of structures that are used to try alternate solutions. Robetta [58] and MODELLER [79] can use prior knowledge in an archive of individual domains or protein fragments to build a complete multi-domain homology model.

Structural biologists rely on various tools not only during structure refinement, but also before and after the experiment, in order to design experiments and analyze structural models, respectively. For example, tools predicting different properties from protein sequence, including protein secondary structure (e.g. JPred4 [80]), intrinsic disorder (e.g. IUPred [81]), or protein crystallization propensity (e.g. PDPredictor [82], XtalPred [83]) utilize information derived from protein structures (IUPred), protein structures and sequence databases (JPred4), or databases of crystallization trials (PDBPredictor, XtalPred). Tools that predict function from the determined structure, such as ProFUNC [84], combine multiple algorithms and databases.

Utilities that analyze the PDB for various interactions include Bio3D [85], MED-SuMo [86], PDBeMotif [87] and the NEIGHBORHOOD database [88]. Although all were built upon the concept about the interactions between different residues in the protein structure network, these databases have different focuses. While Bio3D and MED-SuMo focus upon the analysis of a single structure, PDBeMotif focuses on the search of a pre-defined motif, and NEIGHBORHOOD database focus on the analysis of a group of structures or even the whole PDB. Running one of these databases in the backend would facilitate various types of front-end application [88]. For example, CheckMyMetal (CMM) [89] is a web service for the validation of metal-binding environments in macromolecule structures built on top of the NEIGHBORHOOD database.

6 Concluding Remarks

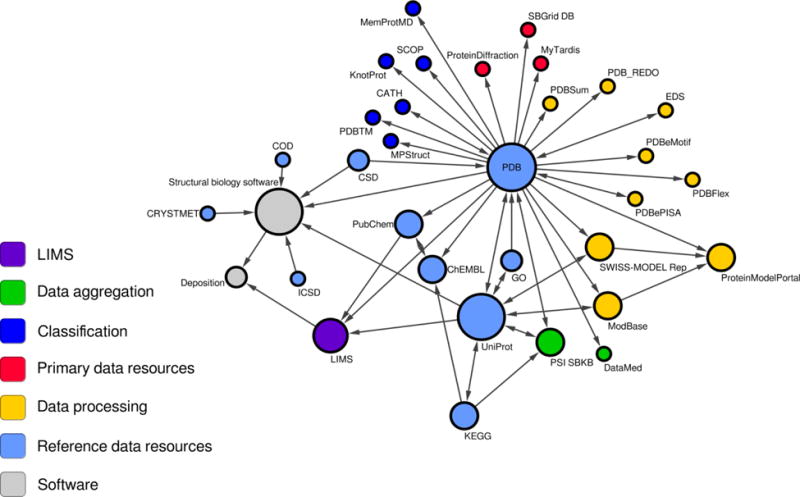

The databases and other data resources used in structural biology are not limited to web portals or servers used to access the databases. The internal use of databases by crystallographic software pointedly illustrates that these resources also underlie various structural biology applications. The use of a database can be completely hidden, because it is utilized only by a particular application. Hence, a scientist may utilize a database without even realizing it. Structural biology data resources are also very deeply interconnected with each other, with reference repositories such as PDB and UniProt being accessed by many others (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Visualization of data exchange between data resources mentioned in this chapter. The selected cross-references are visualized as a graph, where each node corresponds to a particular resource and an edge represent data exchange or reference. The radius of each node illustrates the number of resources that use or reference a given data resource. Different roles of the data resources are color coded. The arrows show the direction of “data flow”.

It is difficult to measure the impact of a data resource. The simplest metric is the number of accesses; these days, however, this number is skewed by automatic robots that scan these resources monthly or even weekly. For that reason, despite significant differences in the usefulness of various structures in the PDB, they have very similar, high number of accesses. Another metric is the number of citations; however, researchers quite often do not cite the servers that they used to create hypotheses and citations in supplementary materials are not indexed. A good illustration of the disparity between the number of citations and the number of accesses is provided by one of the ribosome structures, 4wqf, which has been downloaded 9375 times, but which has been officially cited just once according to the Thomson Reuters Data Citation Index [90]. For that reason, some resources create resource-specific metrics to measure their usefulness. For example, the publishers of the articles describing the servers developed in our laboratory, CMM and Fitmunk, report that these articles were accessed/read 2013 and 505 times as of June 2016. These publications were cited 47 and 1 times, respectively (according to Web of Science in June, 2016). However, internal statistics reveal the servers were used 14625 and 157 times, respectively.

This chapter presents a survey of the data resources that we find useful for structural biology during the sample preparation, experiment planning and execution, structure determination, and structure-function exploration of proteins and nucleic acids, as summarized in Table 2. It also presents the data resources that are sometimes used “behind-the-scenes” but can have significant impact on the productivity, reproducibility, and validity of experiments. In the rapidly evolving world of information technology and data science, we expect that parts of this chapter could become outdated quickly. For example, although we are strong promoters of using DOIs to permanently and unambiguously identify and locate a data resource, in our observation most resources do not currently assign DOIs. When new versions of data resources become available, the old URL may become obsolete and replaced by an updated URL. Therefore, to locate the corresponding data resource mentioned in this chapter, one may want to harness search engines to find the updated location. We would also like to refer the readers to the biosharing.org portal, which hosts references to various data standards, databases, and policies in the life, environmental, and biomedical sciences, and to re3data.org - a global registry of research data repositories for finding other useful data resources not limited to structural biology.

Table 2.

The data resources in structural biology described in this chapter and their characteristics

| Common/ abbreviated name |

Full name | Type | Category1 | Link | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archive | Repo sitor y |

Databas e/AIS |

||||

| Primary data repositories | ||||||

| proteindiffraction.org | Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography | protein diffraction images | − | +++ | ++ | http://proteindiffraction.org/ |

| SBGrid DB | The Structural Biology Data Grid | protein diffraction images | − | +++++ | − | https://data.sbgrid.org/ |

| Store.Synchrotron | Protein diffraction images | ++ | +++ | − | https://store.synchrotron.org.au/public_data/ | |

| Reference repositories | ||||||

| PDB** | Protein Data Bank | macromolecular structures and structure factors | − | ++++ | + | http://wwpdb.org/ |

| CSD | Cambridge Structural Database | small molecular structures | − | ++ | +++ | http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ |

| COD | Crystallography Open Database | small molecular structures | + | +++ | + | http://www.crystallography.net/ |

| ICSD | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database | Inorganic molecular structures | − | ++ | +++ | https://icsd.fiz-karlsruhe.de |

| CRYSTMET | Metals, alloys and intermetallics structures | − | ++ | +++ | ||

| PubChem | PubChem | chemical substances and their activity | − | + | ++++ | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| ChEMBL | chemical substances and their activity | − | + | ++++ | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ | |

| UniProt | Universal Protein Resource | protein sequences | − | + | ++++ | http://www.uniprot.org/ |

| GO | Gene Ontology | function of gene products | − | − | +++++ | http://geneontology.org/ |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes | integrated resource about biological systems | − | − | +++++ | http://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| Derived data resources | ||||||

| Classification | ||||||

| SCOP | Structural Classification of Proteins | protein fold classification | + | ++ | ++ | http://scop.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/scop/ |

| SCOP2 | Structural Classification of Proteins 2 | protein fold classification | − | ++ | +++ | http://scop2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/ |

| SCOPe | Structural Classification of Proteins – extended | protein fold classification | − | + | ++++ | http://scop.berkeley.edu/ |

| CATH | CATH | protein fold classification | − | + | ++++ | http://www.cathdb.info/ |

| PDBTM | Protein Data Bank of Transmembrane Proteins | selection and classification of membrane proteins | − | ++++ | + | http://pdbtm.enzim.hu |

| MPStruc | Membrane Proteins of Known 3-D structure | selection and classification of membrane proteins | − | +++ | ++ | http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/ |

| MemProtMD | A Database of Membrane Proteins Embedded in Lipid Bilayers | selection of membrane proteins and MD simulations in lipid bilayers | − | +++ | ++ | http://sbcb.bioch.ox.ac.uk/memprotmd/ |

| KnotProt | database of “knotted” proteins | − | + | ++++ | http://knotprot.cent.uw.edu.pl/ | |

| Data presentation/analysis/processing | ||||||

| PDBSum | PDBsum | macromolecules and their properties | − | ++ | +++ | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/cgi-bin/pdbsum/GetPage.pl?pdbcode=index.html |

| EDS | Uppsala Electron Density Server | macromolecules andready to use electron density maps | + | + | +++ | http://eds.bmc.uu.se/eds/ |

| RSCB/PDBe/PDBj** | access sites to wwPDB | − | + | ++++ | http://www.rcsb.org/(br/)http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/(br/)http://pdbj.org/ | |

| PDB_REDO | PDB_REDO | automatically re-refined macromolecular structures | + | ++ | ++ | http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/pdb_redo/ |

| ProteinModelPortal ModBase SWISS-MODEL Repository |

automatically generated comparative models | + | ++ | ++ | http://www.proteinmodelportal.org/(br/)http://modbase.compbio.ucsf.edu/modbase-cgi/index.cgi(br/)http://swissmodel.expasy.org/repository/ | |

| PDBePISA | analysis of assemblies and interfaces | +++ | + | + | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/ | |

| PDBFlex | analysis of protein conformation variability | − | − | +++++ | http://pdbflex.org/ | |

| PDBeMOTIF | search of 3D and sequence motifs in proteins | − | − | +++++ | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe-site/pdbemotif/ | |

| Data aggregation | ||||||

| PSI SBKB | Protein Structure Initiative Structural Biology Knowledge Base | + | ++++ | http://sbkb.org/ | ||

| DataMed/bioCADDIE | Biomedial and Healthcare Data Discovery Index Ecosystem | N/A | N/A | N/A | http://biocaddie.org | |

| Data management | ||||||

| SESAME | LIMS | +++++ | http://www.sesame.wisc.edu/ | |||

| LabDB | LIMS | +++++ | https://jurand.med.virginia.edu/labdb | |||

| ISPyB | Information System for Protein crYstallography Beamline | experiment tracking at synchrotrons | +++++ | https://wwws.esrf.fr/ispyb | ||

Each resource was assigned a score (from − to +++++) how well it represents a given category of data resource. As mentioned in the text, the boundaries between particular categories are not well defined, therefore the scores presented here are arbitrary – presented scores are author’s subjective evaluation. “Database” and AIS types have been scored together because the boundaries between these two are especially ill defined.

the RCSB/PDBe/PDBj sites add additional database functionalities and data aggregation on top of the wwPDB repository, therefore are listed separately.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ewa Niedzialkowska, Kasia Handing, Ivan Shabalin, Esther Sheler, Ethan Steen, Cody LaRowe, and Barat Venkataramany for help and numerous discussions/suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HG008424, GM053163, GM117325, GM117080 as well as with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN272201200026C.

Footnotes

Herein we use the term “database” to mean a resource that includes not only a conventional database, but also an interface that facilitates data searches, data retrieval, and data analysis. This alleviates the need to know the internal architecture of the data and the particular query language of the underlying database.

References

- 1.Rose PW, Prlic A, Bi C, Bluhm WF, Christie CH, Dutta S, et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: views of structural biology for basic and applied research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D345–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1214. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ESRF ID30A-3/MASSIF-3 [Internet] 2015 [updated 12/20/2015; cited 4/28/2016]. Available from: http://www.esrf.eu/home/UsersAndScience/Experiments/MX/About_our_beamlines/id30a-3–massif-3.html.

- 3.Stoll C, Schubert G. Data is not information, information is not knowledge, knowledge is not understanding, understanding is not wisdom [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang YH, Rose PW, Hsu CN. Citing a Data Repository: A Case Study of the Protein Data Bank. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UniProt Consortium. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D204–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman MD, Grabowski M, Domagalski MJ, Maclean EM, Chruszcz M, Minor W. Data management in the modern structural biology and biomedical research environment. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1140:1–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0354-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson WF. Structural genomics and drug discovery for infectious diseases. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9(5):507–17. doi: 10.2174/187152609789105713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myler PJ, Stacy R, Stewart L, Staker BL, Van Voorhis WC, Varani G, et al. The Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease (SSGCID) Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9(5):493–506. doi: 10.2174/187152609789105687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A history of storage cost [Internet] 2014 [cited 4/29/2016]. Available from: http://www.mkomo.com/cost-per-gigabyte.

- 10.Elsliger MA, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Wooley J, Wuthrich K, et al. The JCSG high-throughput structural biology pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;F66(Pt 10):1137–42. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110038212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer GR, Aragao D, Mudie NJ, Caradoc-Davies TT, McGowan S, Bertling PJ, et al. Operation of the Australian Store.Synchrotron for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2014;D70(Pt 10):2510–9. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714016174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Androulakis S, Schmidberger J, Bate MA, DeGori R, Beitz A, Keong C, et al. Federated repositories of X-ray diffraction images. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64(Pt 7):810–4. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908015540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terwilliger TC. Archiving raw crystallographic data. Acta Crystallogr. 2014;D70(Pt 10):2500–1. doi: 10.1107/S139900471402118X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer PA, Socias S, Key J, Ransey E, Tjon EC, Buschiazzo A, et al. Data publication with the structural biology data grid supports live analysis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10882. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein FC, Koetzle TF, Williams GJ, Meyer EF, Jr, Brice MD, Rodgers JR, et al. The Protein Data Bank: a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. J Mol Biol. 1977;112(3):535–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westbrook JD, Bourne PE. STAR/mmCIF: an ontology for macromolecular structure. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(2):159–68. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen FH. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Crystallogr. 2002;B58(Pt 3 Pt 1):380–8. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grazulis S, Daskevic A, Merkys A, Chateigner D, Lutterotti L, Quiros M, et al. Crystallography Open Database (COD): an open-access collection of crystal structures and platform for world-wide collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D420–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr900. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belsky A, Hellenbrandt M, Karen VL, Luksch P. New developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design. Acta Crystallogr. 2002;B58(Pt 3 Pt 1):364–9. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102006948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White PS, Rodgers JR, Le Page Y. CRYSTMET: a database of the structures and powder patterns of metals and intermetallics. Acta Crystallogr. 2002;B58(Pt 3 Pt 1):343–8. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102002902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A, et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1202–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bento AP, Gaulton A, Hersey A, Bellis LJ, Chambers J, Davies M, et al. The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1083–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1031. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene LH, Lewis TE, Addou S, Cuff A, Dallman T, Dibley M, et al. The CATH domain structure database: new protocols and classification levels give a more comprehensive resource for exploring evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D291–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl959. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247(4):536–40. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox NK, Brenner SE, Chandonia JM. SCOPe: Structural Classification of Proteins–extended, integrating SCOP and ASTRAL data and classification of new structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D304–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1240. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreeva A, Howorth D, Chothia C, Kulesha E, Murzin AG. SCOP2 prototype: a new approach to protein structure mining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D310–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1242. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozma D, Simon I, Tusnady GE. PDBTM: Protein Data Bank of transmembrane proteins after 8 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D524–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1169. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tusnady GE, Dosztanyi Z, Simon I. Transmembrane proteins in the Protein Data Bank: identification and classification. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):2964–72. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tusnady GE, Dosztanyi Z, Simon I. PDB_TM: selection and membrane localization of transmembrane proteins in the protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D275–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki002. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tusnady GE, Dosztanyi Z, Simon I. TMDET: web server for detecting transmembrane regions of proteins by using their 3D coordinates. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(7):1276–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moraes I, Evans G, Sanchez-Weatherby J, Newstead S, Stewart PD. Membrane protein structure determination - the next generation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(1 Pt A):78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stansfeld PJ, Goose JE, Caffrey M, Carpenter EP, Parker JL, Newstead S, et al. MemProtMD: Automated Insertion of Membrane Protein Structures into Explicit Lipid Membranes. Structure. 2015;23(7):1350–61. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raman P, Cherezov V, Caffrey M. The Membrane Protein Data Bank. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(1):36–51. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sulkowska JI, Rawdon EJ, Millett KC, Onuchic JN, Stasiak A. Conservation of complex knotting and slipknotting patterns in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(26):E1715–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205918109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laskowski RA. PDBsum new things. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D355–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn860. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleywegt GJ, Harris MR, Zou JY, Taylor TC, Wahlby A, Jones TA. The Uppsala Electron-Density Server. Acta Crystallogr. 2004;D60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2240–9. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904013253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. 2004;D60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version~1.3r1. 2010 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shabalin IG, Dauter Z, Jaskolski M, Minor W, Wlodawer A. Crystallography and chemistry should always go together: a cautionary tale of protein complexes with cisplatin and carboplatin. Acta Crystallogr. 2015;D71:1965–79. doi: 10.1107/S139900471500629X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joosten RP, Joosten K, Cohen SX, Vriend G, Perrakis A. Automatic rebuilding and optimization of crystallographic structures in the Protein Data Bank. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(24):3392–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terwilliger TC, Bricogne G. Continuous mutual improvement of macromolecular structure models in the PDB and of X-ray crystallographic software: the dual role of deposited experimental data. Acta Crystallogr. 2014;D70(Pt 10):2533–43. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714017040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper DR, Porebski PJ, Chruszcz M, Minor W. X-ray crystallography: Assessment and validation of protein-small molecule complexes for drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6(8):771–82. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.585154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chruszcz M, Domagalski M, Osinski T, Wlodawer A, Minor W. Unmet challenges of structural genomics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(5):587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haas J, Roth S, Arnold K, Kiefer F, Schmidt T, Bordoli L, et al. The Protein Model Portal–a comprehensive resource for protein structure and model information. Database (Oxford) 2013;2013:bat031. doi: 10.1093/database/bat031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold K, Kiefer F, Kopp J, Battey JN, Podvinec M, Westbrook JD, et al. The Protein Model Portal. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2009;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10969-008-9048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository of annotated three-dimensional protein structure homology models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D230–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh008. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hrabe T, Li Z, Sedova M, Rotkiewicz P, Jaroszewski L, Godzik A. PDBFlex: exploring flexibility in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D423–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krissinel E. Crystal contacts as nature’s docking solutions. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(1):133–43. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gabanyi MJ, Adams PD, Arnold K, Bordoli L, Carter LG, Flippen-Andersen J, et al. The Structural Biology Knowledgebase: a portal to protein structures, sequences, functions, and methods. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2011;12(2):45–54. doi: 10.1007/s10969-011-9106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohno-machado L, Alter G, Fore I, Martone M, Sansone S, Xu H. bioCADDIE white paper - Data Discovery Index. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zolnai Z, Lee PT, Li J, Chapman MR, Newman CS, Phillips GN, Jr, et al. Project management system for structural and functional proteomics: Sesame. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2003;4(1):11–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1024684404761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markley JL, Aceti DJ, Bingman CA, Fox BG, Frederick RO, Makino S, et al. The Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2009;10(2):165–79. doi: 10.1007/s10969-008-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution - from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. 2006;D62:859–66. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim DE, Chivian D, Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W526–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. 2006;D62(Pt 4):439–50. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldschmidt L, Cooper DR, Derewenda ZS, Eisenberg D. Toward rational protein crystallization: A Web server for the design of crystallizable protein variants. Protein Sci. 2007;16(8):1569–76. doi: 10.1110/ps.072914007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. 2011;D67(Pt 4):355–67. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66(Pt 2):213–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–22. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lebedev AA, Young P, Isupov MN, Moroz OV, Vagin AA, Murshudov GN. JLigand: a graphical tool for the CCP4 template-restraint library. Acta Crystallogr. 2012;D68(Pt 4):431–40. doi: 10.1107/S090744491200251X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andrejasic M, Praaenikar J, Turk D. PURY: a database of geometric restraints of hetero compounds for refinement in complexes with macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64(Pt 11):1093–109. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908027388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams PD, Baker D, Brunger AT, Das R, DiMaio F, Read RJ, et al. Advances, interactions, and future developments in the CNS, Phenix, and Rosetta structural biology software systems. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:265–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64(Pt 1):125–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Adrendall WB, de Bakker PIW, Word JM, Prisant MG, et al. Structure validation by C alpha geometry: phi,psi and C beta deviation. Proteins. 2003;50(3):437–50. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL., Jr A smoothed backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins derived from adaptive kernel density estimates and regressions. Structure. 2011;19(6):844–58. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Porebski PJ, Cymborowski M, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Minor W. Fitmunk: improving protein structures by accurate, automatic modeling of side-chain conformations. Acta Crystallogr. 2016;D72(Pt 2):266–80. doi: 10.1107/S2059798315024730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Furnham N, Dore AS, Chirgadze DY, de Bakker PI, Depristo MA, Blundell TL. Knowledge-based real-space explorations for low-resolution structure determination. Structure. 2006;14(8):1313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joosten K, Cohen SX, Emsley P, Mooij W, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. A knowledge-driven approach for crystallographic protein model completion. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64(Pt 4):416–24. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cowtan K. Completion of autobuilt protein models using a database of protein fragments. Acta Crystallogr. 2012;D68(Pt 4):328–35. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911039655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terwilliger TC. Automated main-chain model building by template matching and iterative fragment extension. Acta Crystallogr. 2003;D59(Pt 1):38–44. doi: 10.1107/S0907444902018036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.MoRDa - Automatic Molecular Replacement Pipeline [Internet] 2014 [cited 4/29/2016]. Available from: http://www.biomexsolutions.co.uk/morda.

- 77.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr. 2007;D63(Pt 1):32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trapani S, Navaza J. AMoRe: classical and modern. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64(Pt 1):11–6. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907044460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Webb B, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1137:1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0366-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Drozdetskiy A, Cole C, Procter J, Barton GJ. JPred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W389–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3433–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Babnigg G, Joachimiak A. Predicting protein crystallization propensity from protein sequence. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2010;11(1):71–80. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Slabinski L, Jaroszewski L, Rychlewski L, Wilson IA, Lesley SA, Godzik A. XtalPred: a web server for prediction of protein crystallizability. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(24):3403–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laskowski RA, Watson JD, Thornton JM. ProFunc: a server for predicting protein function from 3D structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W89–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki414. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skjaerven L, Yao XQ, Scarabelli G, Grant BJ. Integrating protein structural dynamics and evolutionary analysis with Bio3D. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Doppelt-Azeroual O, Moriaud F, Adcock SA, Delfaud F. A review of MED-SuMo applications. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9(3):344–57. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909030344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Golovin A, Henrick K. MSDmotif: exploring protein sites and motifs. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:312. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zheng H, Chruszcz M, Lasota P, Lebioda L, Minor W. Data mining of metal ion environments present in protein structures. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102(9):1765–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zheng H, Chordia MD, Cooper DR, Chruszcz M, Muller P, Sheldrick GM, et al. Validation of metal-binding sites in macromolecular structures with the CheckMyMetal web server. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(1):156–70. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Web of Science [Internet] 2016 [cited 05/02/2016]. Available from: http://wokinfo.com/products_tools/multidisciplinary/dci/