Abstract

Background

The bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (SA) is known to induce allergic inflammatory responses, including through secreted staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) superantigens. To quantify indoor environmental exposures to these potential allergens, which may be associated with worse asthma, we developed a method for the assessment of S. aureus and SE in home dust and applied it to a study of homes of inner-city adults with asthma.

Methods

We conducted laboratory experiments to optimize sample processing and real-time PCR methods for detection and quantification of SA (femB) and SEA-D, based on published primers. We applied this method to dust and dust extract from 24 homes. We compared results from real-time PCR to culture-based results from the same homes.

Results

The bacteremia DNA isolation method provided higher DNA yield than alternative kits. Culture-based results from homes demonstrated 12 of 24 (50%) bedrooms were contaminated with S. aureus, only one of which carried a SE gene (SEC). In contrast, femB was detected in 23 of 24 (96%) bedrooms with a median of 1.1 × 106 gene copies detected per gram of raw dust. Prevalence and median copy number (shown in parenthesis) of SE gene detection in bedroom dust was: SEA 25% (1.4 × 102); SEB 63% (1.4 × 103); SEC 63% (1.1 × 103); SED 21% (1.3 × 102).

Conclusions

Our culture-independent method to detect S. aureus and SE in home dust was more sensitive than our culture-based method. Prevalence of household exposure to S. aureus and SE allergens may be high among adults with asthma.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, staphylococcal enterotoxin, superantigen, indoor dust, allergy, asthma

1. Introduction

Indoor home environmental exposures to biotic material, particularly allergens and microbial endotoxin, are known to exacerbate allergic asthma among people with existing disease (Matsui et al., 2008). The bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (SA) also may induce allergic inflammatory host responses, including through secreted staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) superantigens (Bachert et al., 2012b). SA is known to aggravate eczema and a growing body of evidence suggests SA exposure may contribute to the development or exacerbation of a related disease, allergic asthma (Davis et al., 2015; Sinotobin et al., 2015; Song et al., 2014; Bachert et al., 2012a). While microbial exposures have been linked to both protection against and risk for asthma development, it is not known whether SA and SE exposures within the home environment impact respiratory symptoms and lung function in people with asthma.

While methods are established to quantify home environmental allergen exposure, corresponding methods for SA/SE detection and quantification have not yet been validated. In prior studies, microbial DNA-based methods using quantitative PCR (qPCR) methods have demonstrated good reliability and applicability to large cohorts for assessment of microbial exposures in home dust samples (Fujimura et al., 2012; Kaarakainen et al., 2009; Rintala et al., 2008; Scherer et al., 2014). DNA-based methods may provide a less biased estimate of microbial exposures than culture-based methods, which require organism viability and cultivability (Kaarakainen et al., 2009). This may be particularly important for studies, not of acute infection, but of immune modulation in the context of chronic disease outcomes.

While qPCR methods exist to confirm cultured isolates as S. aureus and evaluate whether such isolates carry certain staphylococcal enterotoxin genes (Klotz et al., 2003), no prior study has evaluated these methods for use in the complex environmental matrix of home dust. Hence, we adapted and optimized a microbial DNA-based method for home dust assessment for SA/SE and applied this method, comparing results from qPCR assessment to culture-based results, in a pilot study of the homes of inner-city adults with asthma. We hypothesized that detection of SA would be more common than detection of SEs, which are variably carried by staphylococcal strains, and that gene-based detection would be more sensitive than culture-based detection methods.

2. Methods

2.1 Method evaluation and optimization (Laboratory Study)

2.1.1 Genomic DNA isolation

Two bead-beating DNA Purification kits were compared for DNA isolation performance: BiOstic® Bacteremia and Powerlyzer® Powersoil® (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Each kit was tested using three replicates of: 1) overnight-grown staphylococcal culture (S. aureus ATCC 13565) only; 2) 50 mg of standard house dust (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) combined with overnight-grown staphylococcal culture (“spiked” dust); and 3) 50 mg of standard house dust only. A previous trial in our laboratory showed that qPCR fluorescence threshold values for DNA extracts from 50 mg aliquots of dust did not differ significantly from those from 100 mg aliquots. For each sample that contained staphylococcal culture, two different volumes of culture were tested using calibrated 1μl and 10μl inoculating loops (Fisher Scientific).

Cells from microbial culture were suspended in the bead solutions for each kit, and these suspensions were added to the bead tubes. When dust was used, it was added directly to the bead tube before adding staphylococcal cells from microbial culture. DNA isolation then proceeded according to the manufacturer instructions for each kit. Purified extracts were analyzed for DNA concentration using a Qubit™ 3.0 Fluorometer (LifeTechnologies).

2.1.2 Real-time PCR protocol

TaqMan PCR assays were run as duplex reactions to test for both the femB gene and a single SE gene in each reaction; therefore, four reactions were carried out for each sample in order to test for the presence of four different SE genes (A, B, C and D). The primers and TaqMan probes (Klotz et al., 2003) were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics (Huntsville, AL, USA), as previously published, except the femB probe was labeled with an alternate fluorophore, JOE, rather than FAM, to accommodate the duplex reaction. Reaction mixtures (25 μl final volume) contained 1X TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (no UNG) (Applied Biosystems™); 50pmol each primer; 150nM TaqMan probe; and 5–9μl template DNA. Amplification was carried out using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems™) under the following parameters: 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

2.1.2.1. Detection of femB and SEA genes in spiked dust samples

Real-time PCR was performed using 9μl of DNA template isolated from the dust samples, as described above, to detect femB and SEA genes present in the S. aureus ATCC 13565 strain used for the spiked dust experiment.

2.1.3 Quantification of femB/SE genes

Standard curves for gene copy number were generated for femB and each of SEA-D genes. Plasmids containing the target gene sequences were cloned using the Qiagen PCR CloningPlus Kit (Qiagen; used for enterotoxin genes) or the TOPO® TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen; used for femB), following manufacturer instructions. Plasmids were isolated from transformed cells using the PureLink Quick Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Invitrogen), following manufacturer instructions. Purified extracts were analyzed for DNA concentration as described above. Gene copy number per microliter of stock plasmid solution was then calculated. The stock solution was then serially diluted to obtain concentrations that would provide ten-fold dilutions from 300000 to 30 gene copies per PCR reaction. Duplex real-time PCR reactions were performed, following the protocol described above, using 5μl of template DNA. Three replicates of each standard curve were performed. Quality control strains were used as follows: ATCC 13565 (sea); ATCC 14458 (seb); ATCC 19096 (sec); ATCC 23235 (sed). All quality control strains were S. aureus and therefore carried the femB gene.

2.2. Method application (Field Study)

2.2.1. Sample population

Households were recruited as a systematic subsample (homes of all adult participants with asthma able to be scheduled for home visit attendance by sub-study personnel between January 2014 and December 2015) from a larger-cohort study, “The effect of air quality on the adult asthmatic response (INHALE).” Home dust was collected from participant bedrooms during the enrollment home visit prior to intervention. Homes were recruited irrespective of housing type, number of occupants, or pet-keeping.

2.2.2. Dust collection for qPCR from homes

The participant’s bed and (if needed) bedroom floor dust was collected using a study vacuum fitted with a DUSTSTREAM® adaptor and filter (Indoor Biotechnologies, Charlottesville, USA). The target quantity was one half the filter, regardless of the time required to collect the sample. The total surface area and number of surfaces vacuumed were recorded. The study vacuum was disinfected using quaternary ammonium-based disinfectant wipes between home visits. The adaptor was washed in a deionized water and dilute detergent mixture in a sonicator, air-dried and disinfected with wipes as described above. Raw dust samples from the bed and bedroom floors of asthmatic adults were divided into aliquots: 50mg for direct DNA isolation and 150mg for extraction processing before DNA isolation (see below). If insufficient dust was available for both direct DNA isolation from raw dust and extraction, raw dust was prioritized. The 50mg raw dust for direct DNA isolation then was subjected to the final optimized DNA extraction and qPCR method for S. aureus and SEA-D assessment as described above.

2.2.3. Dust collection for culture from homes

Using autoclaved dry electrostatic cloths as previously described (Davis et al., 2012a), a 30×30cm area of the participant’s pillow and a second 30×30cm area of a dry, dusty surface in the participant’s bedroom, typically the top of the television, was sampled. Personnel wore freshly-laundered scrubs and sterile gloves to perform the collections. A blank cloth was taken in each home to confirm that handling alone did not contaminate cloths. Cloths were placed into sterile stomacher bags for transport to the laboratory.

2.2.4. Culture-based assessment of S. aureus from bedroom surfaces

Electrostatic cloths were subjected to a double-enrichment protocol as previously described (Davis et al., 2012a), with a published modification (Davis et al., 2016) for use of Columbia CNA blood agar in place of blood agar without colistin to enhance specificity for Gram-positive staphylococci. Presumptive staphylococcal isolates were confirmed as S. aureus (SA) using PCR for the S. aureus-specific nuclease gene (nuc) (Sasaki et al., 2010) and for methicillin-resistant (MR-) or methicillin-susceptible (MS-) status via presence or absence, respectively, of the mecA or mecC gene based on a universal primer (Garcia-Alvarez et al., 2011). Carriage of sea-sed genes among confirmed MRSA and MSSA isolates was identified using qPCR as previously described (Klotz et al., 2003).

2.2.5. Home dust extraction

Evaluation of allergens in home dust is a common procedure in studies of participants with asthma; however, this protocol involves use of dust extracts instead of raw dust. In order to compare use of raw dust to dust extract prepared for allergen testing, 150mg of home dust from the same specimens was sieved and then the sieved dust was extracted using a standard protocol (Eggleston et al., 1999). Briefly, a clean sieve was placed over a clean sheet of paper on the floor of a biological safety hood. A dust sample was emptied onto the middle of the sieve mesh. A 1×1 inch square of material from an allergy pillow cover was used to rub the dust through the mesh until all the dust had passed through the sieve. The weight of the sieved dust was measured by first taring a glass storage tube and then adding the dust to the tube. Extraction buffer (phosphate buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20) was added to the dust at a ratio of 1:20 W/V. Tubes were rotated overnight at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged 5 min at 600 × g. Supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. Both the pelleted dust and dust extract for each sample were stored at −20°C until use.

2.2.6 DNA isolation from raw dust and dust extract

DNA was isolated from the raw dust and dust extract samples. For raw dust, a 50 mg sample was measured and placed directly in a BiOstic bead tube. For dust extract, an aliquot of 500μl of the sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 × g, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was then re-suspended using BiOstic bead solution and transferred to a BiOstic bead tube as described above. DNA isolation was carried out for all samples as described above.

2.2.7 Detection and quantification of femB and SE genes in house dust

Real-time PCR was carried out for raw and extracted house dust, as described above, using 9μl of template for each reaction. Resulting Ct values were transformed into gene copy numbers using a conversion algorithm based on the qPCR results from the plasmid standards described above; the conversion was performed in Stata 13 (College Station, TX).

2.2.8. Statistical analysis

Results from the culture-based and the DNA-based methods were descriptively compared. Log-normal data were transformed; qPCR results from raw dust were compared to qPCR results from home dust extract using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

3. Results

3.1. Results from the method evaluation and optimization (Laboratory Study)

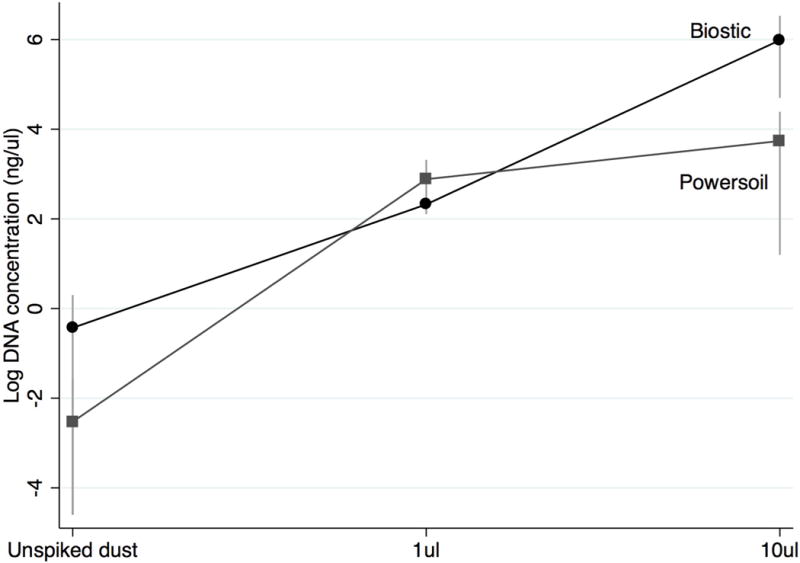

The two kits isolated comparable quantities of DNA from dust samples spiked with 1μl of bacterial culture; however, the bacteremia DNA isolation kit yielded higher concentrations of DNA than the soil DNA isolation kit for spiked samples containing 10μl of bacterial culture (Figure 1). Overall, spiked dust samples that were processed using the soil DNA isolation kit performed poorly in PCR compared to the bacteremia DNA isolation kit. For example, femB and SEA genes were detected by qPCR in all DNA samples isolated from the bacteremia DNA isolation kit while femB and SEA were detected in only one or two identically-prepared samples isolated by the soil DNA isolation kit. Concentrations of DNA isolated from dust samples not spiked with bacterial culture were not significantly different between the two types of kits used (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of DNA yield from dust spiked with calibrated volumes (1μl and 10μl) of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 13565 subjected to extraction using bacteremia and soil DNA isolation kits. n=3 replicates.

3.2. Detection of S. aureus femB and SEA-D genes in home dust by culture and real-time PCR (Field Study)

Between January 2014 and December 2015, sub-study personnel attended 24 home visits and collected dust from the bedroom of the adult with asthma. Application of isolation procedures to samples from bedrooms of adults with asthma demonstrated that while 12 (50%) of 24 homes had surfaces that were culture-positive for SA, 23 (96%) of 24 had detectable SA genes in house dust. Prevalence of SE detection in cultured SA isolates was 4% (1 isolate carrying SEC) but in raw dust was: SEA 25%; SEB 63%; SEC 63%; SED 21%. Real-time PCR results showed that SA was present in home dust at a median concentration of 1.1 × 106 gene copies per gram of raw dust while SE genes were detected at lower concentrations: SEA 1.4 × 102; SEB 1.4 × 103; SEC 1.1 × 103; SED 1.3 × 102 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detection of Staphylococcus aureus (femB) and SEA-D genes in the home dust of adults with asthma, comparing culture-dependent and culture-independent methods, and providing summary values for the number of gene copies detected using the culture-independent method in raw dust.

| Gene | Dust samples, n | Number of positive samples,

n (%) |

Test sensitivity | Number of gene copies per g (raw dust)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jointa | Culture | Real-time PCR | Culture | Real-time PCR | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | ||

|

S.

aureus (femB) |

n=24 | 24 (100) | 12 (50) | 23 (96) | 50% | 96% | 2.5 × 105 | 1.1 × 106 | 3.4 × 106 |

| SEA | n=24 | 6 (25) | 0 | 6 (25) | 0% | 100% | 1.4 × 102 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.7 × 102 |

| SEB | n=24 | 15 (63) | 0 | 15 (63) | 0% | 100% | 1.3 × 102 | 1.4 × 103 | 1.1 × 104 |

| SEC | n=24 | 16 (67) | 1 (4) | 15 (63) | 6% | 94% | 1.3 × 102 | 1.1 × 103 | 5.0 × 104 |

| SED | n=24 | 5 (21) | 0 | 5 (21) | 0% | 100% | 1.3 × 102 | 1.3 × 102 | 1.3 × 102 |

The joint number of positive samples is a combination of results from the culture and real-time PCR protocols; if either protocol detected SA or SE, joint prevalence is positive (gold standard). Sensitivity is calculated by dividing the number positive for each test by the number positive determined by the gold standard (Gordis, 2014).

Q1: 25th percentile; Q2: 50th or median percentile; Q3: 75th percentile

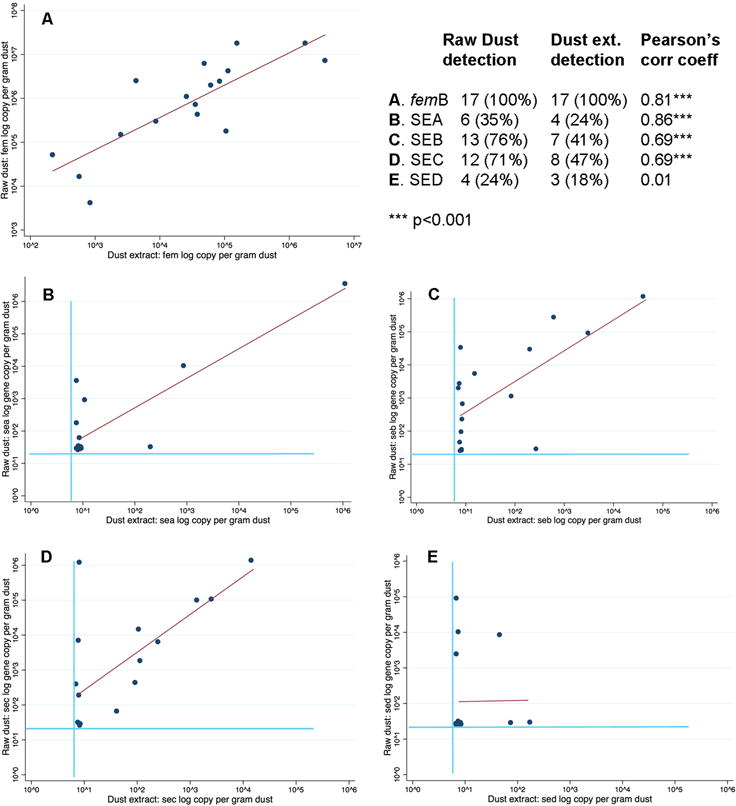

Sufficient dust was available from 17 homes to compare results from raw dust (50mg aliquot) to dust extract (prepared from a 150mg aliquot) from the same dust sample. The median difference in S. aureus DNA yield from raw dust compared to dust extract was 1.24 × 106 gene copies per gram of dust. Dust extract and raw dust demonstrated moderate to strong SA and SEA-C gene correlation (Pearson’s coefficient ~0.70 or higher), but weaker correlation for SED genes (Figure 2A–E).

Figure 2.

Detection of S. aureus (femB) and SEA-D genes in dust from 17 homes, comparing log number of gene copies per gram of dust detected in raw dust versus dust extract. Light-colored lines represent the limits of detection (LOD); points have been jittered to better illustrate the data, given the large numbers of data points at or below the LOD; the dark-colored line represents the line of best fit.

4. Discussion

Our work identified that the majority of Staphylococcus aureus gene copy numbers in the analyzed home dust fell within the limits of detection of our protocol (96%), suggesting that household staphylococcal exposures may be common among urban adults with asthma. Compared to culture-based assessment, bacterial gene-based testing of home dust was more sensitive to detect SA and SE genes. Prior studies have employed culture-based methods to evaluate environmental S. aureus in the homes of participants with asthma (Davis et al., 2012a) or have used culture-independent 16S sequencing to evaluate Staphylococcus genus-level abundance among the suite of dust bacteria (microbiome) to assess risk for development of allergic diseases, including asthma (Ege et al., 2012, Ege et al., 2011, Pakarinen et al., 2008). To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a targeted, culture-independent method to assess S. aureus and staphylococcal enterotoxin genes in dust collected from the homes of people with existing asthma.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to measure staphylococcal enterotoxins in home dust and one of the first to examine S. aureus specifically using culture-independent methods. Our findings of a high prevalence of S. aureus in home environments is consistent with high environmental contamination rates noted for methicillin-resistant S. aureus in the context of culture-based studies on household transmission (Davis et al., 2012b; Fritz et al., 2014; Knox et al., 2012; Uhlemann et al., 2011). Previous work that employed qPCR methods to quantify other bacteria in home dust found that quantities differed between phyla, with lower median concentrations noted for Streptomyces spp. (100–102 cells/mg dust) and Clostridium spp. (102–103 cells/mg dust) and relatively higher median concentrations for Enterobacteriaceae (103 cells/cm2 dust) and Bifidobacteriacae spp. (104 cells/mg dust) (Kaarakainen et al., 2009; Rinatala and Nevalainen, 2006; Scherer et al., 2014; Valknonen et al., 2015).

Our results support the use of this method in either raw dust or dust extract for molecular detection of S. aureus (femB) and SEA-C. However, further evaluation is needed to determine if dust extract performs as well as raw dust for untested staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEE, SEF, etc.) and SED. In addition, it is possible that the strong correlation observed for SEA findings between raw dust and dust extract was influenced by a single outlier. Therefore, researchers collecting home dust for both S. aureus and staphylococcal enterotoxin testing are recommended to reserve at least a 50mg aliquot of raw dust for these tests. Given that we identified lower gene copy numbers in dust extracts compared to raw dust, future studies may examine what steps in the dust extraction process result in the loss of bacterial genes.

The finding of better performance of tests conducted using DNA extracted via the bacteremia DNA isolation kit versus the soil DNA isolation kit was unexpected given that the soil DNA isolation kit is designed for organic soil matrices. The bacteremia DNA isolation kit includes a heat incubation step that may encourage breaking down of bacterial cell walls more thoroughly than is possible with the soil DNA extraction kit. In addition, we noted clogging of the spin filters of the soil DNA extraction kit for samples spiked with 10μl S. aureus cells, which may have contributed to loss of bacterial DNA; we did not note clogging with the spin filters of the bacteremia DNA isolation kit for any samples.

The field study application identified additional sample processing challenges. In particular, processing of raw dust was difficult when large quantities of human hair were incorporated into the vacuumed dust; this was a rare but predictable occurrence given that samples were collected from the bed and bedroom floor. Sample processing and DNA extraction challenges from a sampling containing hair have been noted in a prior study (Fujimura et al., 2012). The process of sieving, which is part of the dust extract protocol for allergen testing, removes larger constituents, like hair, from the home dust and renders the products easier to handle. However, if S. aureus cells are associated with these constituents, then sieving may contribute to discrepancies between findings from raw dust and dust extract.

Several factors limit conclusions from this study. First, the sample size for homes evaluated in the field study may have provided inadequate power to detect correlations between raw dust and dust extract for SED; it is possible that with a larger sample size, we would have concluded that dust extract performed as well as raw dust for all tested enterotoxins. Second, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Replication of these results in larger cohorts, among child participants, and in non-urban settings will enhance confidence in this methodology. Finally, comparison of culture-based and culture-independent findings were limited by evaluation using different samples. We were unable to render the vacuum dust collection process completely sterile given modest resources, and this could represent a source of bias. It is possible that S. aureus isolates were present in the sampling location captured by the vacuum dust method but were not in the sampling location captured by the electrostatic cloth. That said, the culture-based sample collection and the culture-independent sample collection were performed using established protocols and hence, our evaluation should be considered a comparison of the entire protocol.

5. Conclusions

While an increasing body of evidence links human colonization with S. aureus to asthma development and exacerbation, the role of home environmental exposures to this bacterium and its products has yet to be elucidated. Asthma control strategies have focused on reduction of indoor environmental exposures for other biotic material, such as allergens. The protocol and findings presented here together provide a foundation for evaluation of home dust for S. aureus and staphylococcal enterotoxins using culture-independent methods that will be important in future epidemiologic research and intervention strategies to combat the rising epidemic of asthma.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Johns Hopkins Fisher Center Discovery Program (004MAT2014 to E.M.); NIH NIEHS (R01ES023447 to E.M.); NIH NIAID (1K24AI114769 to E.M.); NIH ORIP (K01OD019918 to M.D.); the INHALE project was funded by NIH NIEHS (K24ES021098 to G.D.; and K01ES021789 to S.B.); student support for I.J-B. was funded by NIH NIEHS (1R25ES022865); and NRSA (NHLBI): 1F32HL120396, and KL2 (NIH): 4KL2TR001077-04 (to E.B.). This work was presented at the 2016 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) annual meeting in Los Angeles (L20, abstract published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, Volume 137, Issue 2, AB395).

References

- Bachert C, van Steen K, Zhang N, Holtappels G, Cattaert T, Maus B, Buhl R, Taube C, Korn S, Kowalski M, Bousquet J, Howarth P. Specific IgE against Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: An independent risk factor for asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012a;130(2):376–381.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachert C, Zhang N. Chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma: Novel understanding of the role of IgE ‘above atopy’. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2012b;272(2):133–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02559.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MF, Baron P, Price LB, Williams DL, Jeyaseelan S, Hambleton IR, Diette GB, Breysse PN, McCormack MC. Dry collection and culture methods for recovery of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from indoor home environments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012a;78(7):2474–2476. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06886-11. http://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.06886-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MF, Hu B, Carroll KC, Bilker WB, Tolomeo P, Cluzet VC, Baron P, Ferguson JM, Morris DO, Rankin SC, Lautenbach E, Nachamkin I. Comparison of culture-based methods for identification of colonization with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in the context of cocolonization. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2016;54(7):1907–1911. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00132-16. http://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00132-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MF, Iverson SA, Baron P, Vasse A, Silbergeld EK, Lautenbach E, Morris DO. Household transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococci. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012b;12(9):703–716. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70156-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MF, Peng RD, McCormack MC, Matsui EC. Staphylococcus aureus colonization is associated with wheeze and asthma among US children and young adults. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135(3):811–813.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.052. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ege MJ, Mayer M, Schwaiger K, Mattes J, Pershagen G, van Hage M, Scheynius A, Bauer J, von Mutius E. Environmental bacteria and childhood asthma. Allergy. 2012;67(12):1565–1571. doi: 10.1111/all.12028. http://doi.org/10.1111/all.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ege MJ, Mayer M, Normand AC, Genuneit J, Cookson WOCM, Braun-Fahrländer C, Heederick D, Piarroux R, von Mutius E. Exposure to environmental microorganisms and childhood asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(8):701–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007302. http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1007302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston PA, Wood RA, Rand C, Nixon WJ, Chen PH, Lukk P. Removal of cockroach allergen from inner-city homes. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999;104(4):842–846. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70296-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Singh LN, Thompson RM, Wallace MA, Whitney K, Al-Zubeidi D, Burnham CAD, Fraser VJ. Contamination of environmental surfaces with Staphylococcus aureus in households with children infected with methicillin-resistant S. aureus. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(11):1030–1038. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1218. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura KE, Rauch M, Matsui E, Iwai S, Calatroni A, Lynn H, Mitchell H, Johnson CC, Gern JE, Togias A, Boushey HA, Kennedy S, Lynch SV. Development of a standardized approach for environmental microbiota investigations related to asthma development in children. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2012;91(2):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.08.016. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Álvarez L, Holden MTG, Lindsay H, Webb CR, Brown DFJ, Curran MD, Walpole E, Brooks S, Pickard DJ, Teale C, Parkhill J, Bentley SD, Edwards GF, Girvan EK, Kearns AM, Pichon B, Hill RLR, Larsen AR, Skov RL, Peacock SJ, Maskell DJ, Holmes MA. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine populations in the UK and Denmark: a descriptive study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11(8):595–603. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis L. Epidemiology. Fifth ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarakainen P, Rintala H, Vepsäläinen A, Hyvärinen A, Nevalainen A, Meklin T. Microbial content of house dust samples determined with qPCR. The Science of the Total Environment. 2009;407(16):4673–4680. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.04.046. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M, Opper S, Heeg K, Zimmermann S. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins A to D by real-time fluorescence PCR assay. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(10):4683–4687. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4683-4687.2003. http://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.10.4683-4687.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J, Uhlemann AC, Miller M, Hafer C, Vasquez G, Vavagiakis P, Shi Q, Lowy FD. Environmental contamination as a risk factor for intra-household Staphylococcus aureus transmission. PloS one. 2012;7(11):e49900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049900. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049900.t004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui EC, Hansel NN, McCormack MC, Rusher R, Breysse PN, Diette GB. Asthma in the inner city and the indoor environment. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2008;28(3):665–686. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.03.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakarinen J, Hyvärinen A, Salkinoja-Salonen M, Laitinen S, Nevalainen A, Mäkelä MJ, Haahtela T, Von Hertzen L. Predominance of Gram-positive bacteria in house dust in the low-allergy risk Russian Karelia. Environmental Microbiology. 2008;10(12):3317–3325. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01723.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintala H, Nevalainen A. Quantitative measurement of streptomycetes using real-time PCR. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2006;8:745–749. doi: 10.1039/b602485h. http://doi.org/10.1039/B602485H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintala H, Pitkäranta M, Toivola M, Paulin L, Nevalainen A. Diversity and seasonal dynamics of bacterial community in indoor environment. BMC Microbiology. 2008;8:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-56. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-8-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Tsubakishita S, Tanaka Y, Sakusabe A, Ohtsuka M, Hirotaki S, Kawakami T, Fukata T, Hiramatsu K. Multiplex-PCR method for species identification of coagulase-positive staphylococci. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(3):765–769. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01232-09. http://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01232-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer E, Rocchi S, Reboux G, Vandentorren S, Roussel S, Vacheyrou M, Raherison C, Millon L. qPCR standard operating procedure for measuring microorganisms in dust from dwellings in large cohort studies. The Science of the Total Environment. 2014:466–467. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.054. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sintobin I, Keil T, Lau S, Grabenhenrich L, Holtappels G, Reich A, Wahn U, Bachert C. Is immunoglobulin E to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins associated with asthma at 20 years? Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2015;26(5):461–465. doi: 10.1111/pai.12396. http://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WJ, Chang YS, Lim MK, Yun EH, Kim SH, Kang HR, Park HW, Tomassen P, Choi MH, Min KU, Cho SH, Bachert C. Staphylococcal enterotoxin sensitization in a community-based population: a potential role in adult-onset asthma. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2014;44(4):553–562. doi: 10.1111/cea.12239. http://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlemann AC, Knox J, Miller M, Hafer C, Vasquez G, Ryan M, Vavagiakis P, Shi Qiuhu, Lowy FD. The environment as an unrecognized reservoir for community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300: a case-control study. PloS one. 2011;6(7):e22407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022407. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022407.t004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen M, Wouters IM, Täubel M, Rintala H, Lenters V, Vasara R, Genuneit J, Braun-Fahrländer C, Piarroux R, von Mutius E, Heederik D, Hyvärinen A. Bacterial exposures and associations with atopy and asthma in children. PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0131594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]