Abstract

Objective

Adjusting to cancer is an ongoing process, yet few studies explore this adjustment from a qualitative perspective. The aim of our qualitative study was to understand how patients construct their experience of adjusting to living with cancer.

Method

Qualitative analysis was conducted of written narratives collected from four separate writing sessions as part of a larger expressive writing clinical trial with renal cell carcinoma patients. Thematic analysis and constant comparison were employed to code the primary patterns in the data into themes until thematic saturation was reached at 37 participants. A social constructivist perspective informed data interpretation.

Results

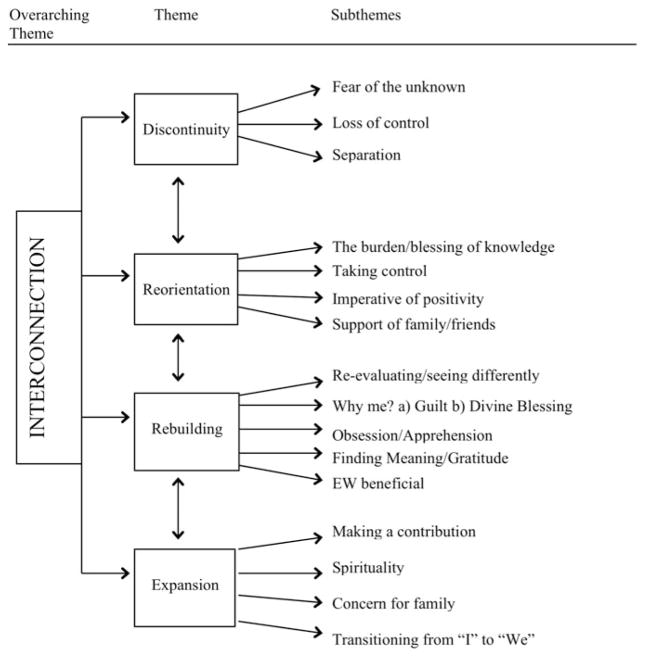

Interconnection described the overarching theme underlying the process of adjusting to cancer and involved four interrelated themes: (1) discontinuity—feelings of disconnection and loss following diagnosis; (2) reorientation—to the reality of cancer psychologically and physically; (3) rebuilding—struggling through existential distress to reconnect; and (4) expansion—finding meaning in interconnections with others. Participants related a dialectical movement in which disruption and loss catalyzed an ongoing process of finding meaning.

Significance of results

Our findings suggest that adjusting to living with cancer is an ongoing, iterative, nonlinear process. The dynamic interactions between the different themes in this process describe the transformation of meaning as participants move through and revisit prior themes in response to fluctuating symptoms and medical news. It is important that clinicians recognize the dynamic and ongoing process of adjusting to cancer to support patients in addressing their unmet psychosocial needs throughout the changing illness trajectory.

Keywords: Adjustment, Qualitative, Expressive writing, Kidney cancer, Meaning-making

INTRODUCTION

Change and uncertainty characterize both the physical manifestation and psychosocial experience of cancer. Such precariousness can contribute to ongoing psychological distress across the illness continuum (Zabora et al., 1997), an outcome known to adversely affect survivors’ quality-of-life (QoL) (Hewitt et al., 2006). The biopsychosocial nature of cancer necessitates an understanding of the human dimensions of the cancer experience alongside its physical processes (Bultz & Carlson, 2006). Researchers characterize the psychosocial challenges people with cancer experience as “ontological suffering,” the “existential plight of cancer,” or the “search for meaning” (Weisman & Worden, 1977; Arman & Rehnsfeldt, 2003). These terms describe similar existential and psychological processes wherein individuals struggle to reshape the shattered meaning and structure of their lives following the profound “biographical disruption” of confronting mortality (Bury, 1982; Becker, 1997; Park & Folkman, 1997). Some studies depict this process as positive psychological adjustment (Lee et al., 2004; Stanton et al., 2006; Horgan et al., 2011), while others report the development of greater distress and negative affect (Kernan & Lepore, 2009) or a complex and dialectical cancer experience entailing both growth and loss (Bruce et al., 2011; Sachs et al., 2013).

These inconsistencies in the literature may point to the complexities and paradoxes (Leal et al., 2015) of the cancer experience. Patients’ narrative accounts are particularly useful for understanding the cancer experience, as they elucidate the nature of the continuing process of the illness trajectory, giving voice and shape to people’s experience by creating and giving meaning to their suffering (Kleinman, 1988; Charmaz, 1991; Frank, 2013). Qualitative analysis centers on narrative content and process, as individuals perceive, understand, and find meaning in their illness experiences through narration (Hydén, 1997). Recent reviews on the existential (Henoch & Danielson, 2009) and traumatic (Hefferon et al., 2009) impact of cancer noted that qualitative approaches can capture the complex and often dynamic psychosocial processes of living with cancer, filling a recognized gap in the research literature. Through systematic investigation of the richly detailed descriptions of individual narratives, qualitative methods map common patterns, producing knowledge and evidence about shared processes within the human experience.

To further uncover the complexity of the cancer adjustment process, we undertook a qualitative analysis of narratives collected as part of an expressive writing (EW) intervention with participants who had kidney cancer (renal cell carcinoma; RCC) (Milbury et al., 2014) (note: the terms “RCC” and “cancer” are used interchangeably in this article). We used thematic analysis and constant comparison to understand how people at different stages of cancer construct their experiences of adjustment across the illness trajectory. Our analysis of these shared stories lays bare the psychosocial reality of suffering beyond the clinical gaze, chronicling how people adjust to cancer, thus contributing to how clinicians can support patient well-being (Lee et al., 2004). Understanding the experience and repercussions of living with cancer is vital to providing quality care and support through diagnosis, treatment, and recovery, as well as designing responsive psychosocial interventions.

METHODS

The Parent Study

The original randomized controlled trial assessed the physical and psychological aspects of QoL at four timepoints post-intervention (Milbury et al., 2014) investigating the QoL benefits of EW for patients with RCC. We examined patients with RCC because this population is severely understudied regarding supportive care research. Respondents had either completed surgery six months previously or were receiving systemic or targeted chemotherapy. The control or neutral writing (NW) group wrote factually about health-related topics, while the EW group wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings regarding their cancer experience. Participants completed four 20-minute writing assignments at home over a 10-day period, with a 1- to 3-day interval between sessions. Table 1 provides the EW session prompts.

Table 1.

Prompts for the EW intervention

General instructions for each session:

|

Participants and Sampling

Patients recently diagnosed with stage I–IV RCC were eligible for participation. Patients had no serious intercurrent medical illness requiring hospitalization, were ≥18 years old, and able to read, write, and speak English. Some 277 participants were randomized to the EW (n = 138) and NW (n = 139) groups. The qualitative analysis used stratified purposeful sampling to select participants exclusively from the EW group (Table 2) according to disease stage to achieve greater variation (Patton, 2001). Sampling continued until thematic saturation was reached when through frequent meetings analyst-corroborated data analysis yielded no unique themes. Thematic saturation was achieved at 37 respondents. This study is covered by ongoing institutional review board approval. Each participant provided informed consent and completed all four writing assignments.

Table 2.

Demographic and medical characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | n | % | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 16 | 43.24 | |

| Male | 21 | 59.46 | |

| Age (years) | 40–71 | ||

| Education | |||

| High school graduate or some college | 11 | 29.73 | |

| College graduate or higher | 26 | 70.27 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 32 | 86.48 | |

| Latino | 3 | 8.10 | |

| Other | 2 | 5.4 | |

| Income | |||

| $20,000–50,000 | 10 | 27.02 | |

| $50,000–$100,000 | 27 | 72.97 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time | 19 | 51.35 | |

| Part-time | 6 | 16.21 | |

| Unemployed | 1 | 2.70 | |

| Retired | 11 | 29.73 | |

| Group stage | |||

| I | 11 | 29.73 | |

| II | 6 | 16.21 | |

| III | 4 | 10.81 | |

| IV | 13 | 35.13 | |

| Missing | 2 | 5.40 | |

| Surgery | 18 | 48.65 | |

| Systemic treatment | 15 | 40.54 | |

| Targeted treatment | 6 | 16.22 | |

| Time since diagnosis (days) | |||

| 0–100 | 19 | 81.03 | |

| 100–400 | 3 | 8.1 | |

| 400–1,000 | 5 | 13.51 | |

| over 1,000 | 6 | 16.22 | |

| Cancer other than RCC | 6 | 16.22 | |

| Recurrence | 5 | 13.51 | |

RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

Qualitative Analysis: Thematic Analysis and Constant Comparison

Diverse analysts experienced in qualitative research, a cultural anthropologist, a qualitative methodology specialist, and a psychology student independently analyzed the data to ensure interpretive validation and diminish researcher bias. Analysis focused on participants’ narratives of adjusting to cancer, reassessing their life histories in the wake of a cancer diagnosis (Bury, 1982; Becker, 1994). We adopted a social constructionist perspective which assumes that meaning and reality are socially constructed through language as the fundamental vehicle for social interactions. Thus, examining participants’ narratives reveals how they construct their experiences (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). Deidentified patient narratives were uploaded into ATLAS.ti to facilitate data management. This analysis utilized inductive thematic analysis and constant comparison (Tuckett, 2005; Braun & Clarke, 2006), as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Steps taken in qualitative analysis to ensure rigor

| Familiarization | The first stage entailed familiarization with the data, reading and rereading respondents’ narratives, noting salient ideas and patterns for an overview of all the data and generating of initial codes. |

| Development of initial codes | Three analysts experienced in qualitative research independently inductively coded 10 transcripts, and then met to review, compare, and define codes establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria for development of initial codes. The coding framework remained open to refinement as the analysis proceeded through constant comparison and inductive thematic analysis. |

| Systematic application of codes | Application of initial codes systematically to all the data, using constant comparison to move between individual narratives and the entire data set to ensure coherence and consistency in development of categories and themes. |

| Constant comparison | Through constant comparison of codes both within and across individual narratives, emergent and recurring patterns were merged into categories and themes drawn from the data. |

| Reviewing of themes | We compared and discussed interpretations to reach consensus, to further refine emerging themes, to assure accuracy between integration of data and interpretations, and to ensure that themes were appropriate. |

| Refining and linking themes | Ongoing analysis refining themes and links between themes to form the coherent overall story told by the analysis. Themes were inductively derived from the data. |

| Peer debriefing | To enhance credibility, each step of the analysis was reviewed in periodic meetings of the analytic team, and findings were discussed by the research team to ensure applicability and accuracy between integration of data and interpretation, verifying that assertions were supported by the data. |

| Use of quotes | Participants’ verbatim quotes are used to substantiate analytic findings, providing evidence of how the data built the interpretation. |

RESULTS

Meta-Theme: Interconnection

The overarching theme framing adjusting to RCC was interconnection—describing the common process uniting respondents’ experiences of finding meaning in living with cancer from within an awareness of their mortality. For most of us, knowledge of our mortality is merely theoretical. On an everyday level, we live with an illusory sense of immortality. A cancer diagnosis, however, reveals the hidden truth of our mortality. As one participant stated, “My immortality I thought I had isn’t there after all” [#635].

Respondents narrated a transition described through four interconnected themes: discontinuity, reorientation, rebuilding, and expansion (detailed below; see Figure 1). The narratives chronicle a dialectical movement where disruption and loss catalyzed a process of reorientation, rebuilding meaning, and moving onto appreciation of life as expanded interconnection. Each of these four themes interacts and affects the other in an ongoing, complex, nonlinear process. While participants relate a general transition from diagnosis to expansion, the trajectory described is iterative, as moving through these different themes they often revisit a previous theme according to fluctuating symptoms, medical news, and the presence or absence of support:

November and December were dark months. I found myself sliding into a depression I couldn’t retrieve myself from . . . apprehensive about this follow-up in January. Did they get it all? Is it over? [#234]

Fig. 1.

Conceptual frame of interconnection.

The raw emotional experiences described are not discrete but overlap, portraying a fluid, messy, and dynamic movement along the cancer trajectory. Interconnection describes the connections between these themes and the quality of expansion as the transformed meaning of life.

Themes

Discontinuity and Loss Following Diagnosis

Participants recounted how a cancer diagnosis brought the initial shock of facing their own mortality:

When I discovered in June I had RCC on each kidney, my world came to a screeching halt! The first thing I wondered was, would I be here for Christmas? [#234]

Experiencing an abrupt disruption in their normal lives initiated a transition process expressed by the interrelated categories of fear of the unknown, loss of control, and separation:

You have depended on this corporeal being for all these years, and it has let you down. Now the control of your body has slipped from your hands out to doctors, nurses, and new technology. You readily give them control, but only in return for your freedom. You desperately want to be free of this overwhelming dread, which hangs over your head. Every action is tempered by this cancer you do not control . . . We know life is forever changed. [#509]

These narratives convey the sense of discontinuity that respondents experience in facing their uncertain future after a cancer diagnosis. Others related feeling “so alone,” having been separated by this experience:

Can’t tell friends and family [about the aloneness]—they’ll think they didn’t do enough. Lasting image—the two-hour abdominal ultrasound—cold, empty room; abrupt doctor w/zero bedside manner. Feeling so alone. So alone. [#231]

These feelings of isolation and estrangement express the disconnectedness respondents experienced with the “overwhelming dread which hangs over your head,” which is not shared by those living a “normal” life.

Reorientation to Cancer Psychologically and Physically

Participants struggled to reorient to the new reality of cancer both physically and emotionally. For all, reorientation entailed managing the embodiment of cancer by addressing the immediacy of treatment. Turning to the practical also helped anchor and focus participants during an emotionally turbulent time. Handling these physical and emotional challenges took the form of: (1) the burden/blessing of knowledge; (2) taking control; (3) the imperative of positivity; and (4) support of family and friends. Participants sought information about their condition to allay anxiety:

As things went along and I learned more about cancer, the worrying got easier. [#322]

Conversely, being informed about cancer could also be disquieting:

Everyone is touched by this affliction. I’ve read a lot about cancer, treatments, survival, projections . . . My dad, granddad, and uncle all died of complications brought on by prostrate cancer . . . These statistics weigh heavily on your mind. [#234]

By taking control of treatment options, respondents felt they were regaining the control lost to the precipitous calamity of cancer:

When I finally took charge of my illness and contacted MD Anderson, I started to feel much more confident . . . but more than that I was able to get back in control of my life. As soon as I was accepted as a patient, I started feeling really good . . . before I took charge I was waking up every night and worrying. [#491]

Others sought to address their existential distress through controlling their attitude. One woman who expressed substantial emotional turbulence, anger, and existential distress in her first three narratives suddenly decided that she must adopt a positive attitude in her fourth:

I’ve been working on this attitude of mine. I’ve been reading about cancer and how attitude is everything . . . I’m going to stand up to this illness and make it go away! Wait ‘til my doctor sees me next . . . I know I can will this away. [#336]

In forcing themselves to be positive, participants were subtly aware that this exacerbated experiences of distress and loss:

I always put on my “happy face” when discussing it . . . I have “Cancer Lite.” No chemo, no radiation, stage I, successful operation. So by doing my “Cancer Lite” routine I bury my feelings of frustration, anger, and loss . . . this “Cancer Lite” feels false and unreal. [#231]

These desperate, forced attempts to will a positive attitude into an imperative were distinct from accounts where respondents developed optimism, through appreciation of supportive family and friends:

While I don’t recommend cancer as a life encounter, my experience is along with the devastation it wreaks there’s a positive side to the experience, at least for those of us with supportive family and friends. Being thankful for and appreciative of good family, good friends, and good doctors must be balanced alongside the associated hardships. [#276]

Support of family and friends was crucial to addressing the physical and emotional challenges of cancer and to finding meaning and benefit in the illness experience. Participants related this sustenance was “what keeps you going,” the constant that grounded them in the midst of the bewildering changes of adapting to cancer. Others, however, felt estranged from loved ones:

I don’t ever talk to my family and friends about this because they just won’t talk about it. [#293].

Rebuilding a New Life and Meaning

Participants sought to make meaning of their illness experience during and after treatment through reevaluating their sense of self, relationships with others, spirituality, and the meaning of life. By engaging in an intrapersonal inquiry, they rebuilt a life transformed by the knowledge and experiential suffering of impending death. These reflections were expressed as “Why me?”—articulated both as guilt and as a divine blessing, obsession/apprehension, reevaluating/finding meaning/gratitude, and EW as beneficial to adjustment. Some respondents articulated obsession and guilt regarding cancer:

I think of my cancer several times during the day. It doesn’t go away. This has floored me. It’s left me doubting everything to do with me!! What I think, how I feel, the way I pray, the way I love, my faith, my fear of the hereafter. I believe in God. I’m not afraid to die, but what I fear is if he has truly forgiven me. Cancer has brought into the present what wrongs I’ve done in the past . . . Why me? [#222]

The anxious doubt, obsession, and guilt this woman expressed led to contradictory feelings indicating difficulty in confronting her suffering. Other participants, however, perceived cancer as a blessing:

Then you ask why? But there is no answer for this . . . So why is because God has decided this is the cross you should bear . . . To make you whole to enter the next life . . . So accept this trial from God. [#509]

Rather than engaging in self-recrimination, these patients accepted cancer as “a new chance in life” [#224], leading to reevaluation/finding meaning and gratitude:

Cancer does put fear into one’s mind, it also opens up one’s eyes. I truly feel this is God’s way to slow me down and open my eyes . . . I am a blessed person. I feel in many ways God has let me see deep inside my soul, and it’s up to me to take the proper pathway. [#618]

A third of our participants explicitly mentioned that telling their stories was beneficial to their adjustment process:

I’m extremely thankful my recovery is doing so well . . . Being able to put my thoughts down on paper has helped me look past what’s happened, and start looking to the future . . . I’d highly recommend this writing exercise as a final part of recovery therapy. [#234]

In these quotes, respondents articulate how through self-reflection they sought meaning in reevaluating and transforming the suffering endured with cancer. Many related how getting in touch with their illness experience was crucial to transitioning through the challenges of cancer toward adjustment.

Expansion as Connecting and Giving to Others

Respondents related that through the interconnected and ongoing nature of this process they developed an awareness and appreciation of contributing altruistically to an expansive life, which formed the basis for reintegrating into life and living the future. These altered life values were expressed in the interrelated forms of making a contribution, spirituality, concern for family, and transitioning from an “I” to a “we” existence. Participation in the expansion of life was often expressed spiritually as contributing to something larger than oneself:

Cancer is part of my personal ministry to let others know having cancer can be a blessing regardless of the outcome. [#529]

Concern for family was prominently expressed both as (1) a sense of loss as cancer threatened sharing life with family and (2) contributing to the family’s future well-being:

You see I’m not ready to go, not regarding leaving my husband and family. No one wants to leave their loved ones. I want to see my new granddaughter crawl, walk, and call my name. [#415]

Experiencing life is what life is. Nothing more, nothing less. Giving of oneself makes life, receiving is a by-product of giving. In living my life this way, it’s the one thing I wish to pass on to my kids. [#234]

Transitioning from an “I” to a “we” existence expresses awareness of living with an expanded sense of self, one that is inclusive of others—family, other cancer sufferers, and humanity:

We all have to accept what is in store for us. We all struggle in our lifetime. [#635]

DISCUSSION

These findings describe the common patterns reported across a heterogeneous group of RCC survivors on the human experience of ongoing adjustment to cancer in reevaluating their illness experience in order to find meaning in interconnection. The theme interconnection describes a dialectic of loss and recovery; by encountering loss, an awareness of the value of life as expansive communion with, and continuity through, others develops. Respondents chronicle a transition starting with: (1) discontinuity, following a cancer diagnosis, prompting (2) reorientation to the biopsychosocial reality of cancer, to (3) rebuilding, seeking ways to reintegrate their shattered lives, and (4) expansion, developing a framework that values life as expanded interconnections with self and others. In confronting mortality, participants reclaimed a sense of immortality through an existential reevaluation of the meaning and purpose of life founded upon contributing to an expansive awareness of a shared humanity. This is an expanded view of self and life. Other studies have reported the development of increased empathy and connection with humanity in facing life-threatening illnesses (Schwartzberg, 1994; Barakat et al., 2006).

The life-threatening, uncertain, and persistent nature of cancer describes a precarious reality requiring a flexible and evolving process in adjusting to this condition. The meta-theme of interconnection describes such a dynamic adjustment process. Participants suggest that the dialectic between the states in this process drove the transformation of the meaning of life as expansion. Value is found precisely in the dialectic of “balancing . . . devastation . . . and the positive side of the experience” [#276]. This involves a framework in which life as expansiveness has value whether experienced as suffering or blessing, where “having cancer can be a blessing regardless of the outcome” [#529]. This is a view beyond the merely dualistic, one grounded in the value of continuing, expanded interconnection.

Our analysis aligns with Becker’s (1994; 1997) work on the complex struggle to create continuity within the chaotic disruption of illness. The transformational process outlined also substantiates Moch’s (1989) “health within illness” model, in which “getting in touch with” the illness experience expands the human potential, and posttraumatic growth models (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2006; Zoellner & Maercker, 2006) that portray the seeming contradiction of growth and expansion that emerge from engaging openly with psychological suffering (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995; Taylor, 2000). Given this dialectical nature of adjustment, identifying which factors are beneficial or harmful to this process is complex. Our study findings indicate that facile interpretations of suffering as “bad” and positivity as “good” cannot adequately portray the complexity of the cancer experience. Rather, attention needs to be placed on adjustment as an ongoing developmental and dialectical process. Participants’ diverse experiences reveal a distinction between the development and forcing of positivity. Those embracing suffering and mortality developed positive meaning in expansion and interconnections with others. Conversely, those who approached positivity as an imperative and a magic bullet that would save them psychologically and physically were desperately attempting to diminish their pain, fear, and suffering. Instead, avoiding pain only exacerbated their distress, as emotional avoidance curtails articulation, and thus processing, of these experiences in the transformative space found in our shared human experience. Our findings support research that has indicated that social constraints inhibiting or preventing discussion of illness impedes the social-cognitive processing of these experiences, resulting in poorer psychological adjustment (Lepore, 2001; Schmidt & Andrykowski, 2004).

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

As a qualitative study, our findings are not generalizable, reflecting the experiences of this group of people with RCC, but they may be applicable to other populations. However, our findings concur with other researchers describing the transformation of the psychosocial distress of the cancer experience into positive growth in other cancer populations, supporting the commonality and applicability of this process across different cancer populations (Taylor, 2000; Andrykowski et al., 2008). Working with solely written narratives resulted in a static dataset, limiting further clarification and exploration of emergent themes. Although the aim to describe adjusting to cancer did not specifically guide data collection, respondents’ narration of their illness experiences is naturally framed as a process through the use of unconscious structures, conventions, and norms by which they find coherence and meaning through narration (Green & Thorogood, 2004). Due to the nature of the database and the intent of this manuscript, we were also not able to conduct analyses examining potential differences in outcomes related to demographic, medical, or temporal characteristics.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

While supporting other studies that highlighted the irrevocable changes cancer can bring about in survivors’ lives (Arman & Rehnsfeldt, 2003; Andrykowski et al., 2008; Kenne Sarenmalm et al., 2009), our work contributes to an understanding of the iterative and dialectical nature of the cancer adjustment process. Participants reported that the reiteration of this process was stimulated by ongoing surveillance, given the uncertainties and mutability of cancer, persistent adverse treatment effects, and fears of recurrence accompanying regular medical follow-ups. As these phenomena are common across many cancers, this study contributes to the observable, but often forgotten, crucial understanding of the dynamic as opposed to static nature of the cancer trajectory.

In summary, this analysis affirms adjustment as an ongoing dynamic existential process requiring monitoring by clinicians across the survivorship trajectory. Thus, these findings suggest that supportive care professionals need to attend to survivors’ changing psychosocial needs, acknowledging, facilitating, and coaching them in strategies for managing and preventing distress or finding benefit, as appropriate. Participants confirm that empathetic social support facilitated social-cognitive transition through providing a safe environment for articulating, understanding, and reintegrating distressing events and feelings (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Brennan, 2001) in the transformative space of interrelatedness. However, efforts to find benefit during the initial stages of managing distress can be associated with avoidance and therefore negative psychological adjustment, underscoring the importance of the timing of such interventions (Tomich & Helgeson, 2004). Confronting mortality and the existential suffering it engenders is disturbing, making visible the common mortality we all share. Clinicians are in a unique position to provide empathetic care but may require training to address their own discomfort regarding human suffering and mortality to assist patients in doing the same (Clayton et al., 2005). Moreover, as adjustment is a dynamic construct changing over time (Cox, 2003; Knobf, 2011), supportive care may be most effective if its delivery is context- and patient-related.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by NCI grant R01CA090966 (PI, Lorenzo Cohen, PH.D.) and NIH/NCCIH 1 K01 AT007559 (PI, Kathrin Milbury, PH.D.). The authors thank Velckis Gonzalez for assistance with data analysis. We are also most grateful to all the study participants for generously sharing their experiences.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Andrykowski M, Lykins E, Floyd A. Psychological health in cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.007. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3321244/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arman M, Rehnsfeldt A. The hidden suffering among breast cancer patients: A qualitative metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(4):510–527. doi: 10.1177/1049732302250721. Available from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1049732302250721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat LP, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Post-traumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(4):413–419. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058. Epub ahead of print Aug 10, 2006. Available from https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Metaphors in disrupted lives: Infertility and cultural constructions of continuity. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1994;8(4):383–410. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Disrupted Lives: How People Create Meaning in a Chaotic World. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berger PL, Luckmann T. The Social Construction of reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1991. Available from http://per-flensburg.se/Berger%20social-construction-of-reality.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. Available from http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/11735/2/thematic_analysis_revised_-_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J. Adjustment to cancer: Coping or personal transition? Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<1::aid-pon484>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A, Schreiber R, Petrovskaya O, et al. Longing for ground in a ground(less) world: A qualitative inquiry of existential suffering. BMC Nursing. 2011;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-2. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3045972/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign. Future directions in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(2):93–95. doi: 10.1002/pon.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1982;4(2):167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. Available from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939/pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Good Days, Bad Days: The Self in Chronic Illness and Time. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1991 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, et al. Discussing end-of-life issues with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: A qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2005;13(8):589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0759-2. Epub ahead of print Jan 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K. Assessing the quality of life of patients in phase I and II anti-cancer drug trials: Interviews versus questionnaires. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(5):921–934. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank AW. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 2. London: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N. Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(Pt. 2):343–378. doi: 10.1348/135910708X332936. Available from http://www.katehefferon.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Hefferon-Grealy-Mutrie-BJHP.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henoch I, Danielson E. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: An integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(3):225–236. doi: 10.1002/pon.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. An American Society of Clinical Oncology and Institute of Medicine Symposium; Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan O, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Experiencing positive change after a diagnosis of breast cancer: A grounded theory analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(10):1116–1125. doi: 10.1002/pon.1825. Epub ahead of print Aug 23, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydén L. Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1997;19(1):48–69. Available from https://test.qmplus.qmul.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/158532/mod_book/chapter/3334/Illness%20and%20Narative.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma. New York: The Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kenne Sarenmalm E, Thoren-Jonsson AL, Gaston-Johansson F, et al. Making sense of living under the shadow of death: Adjusting to a recurrent breast cancer illness. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(8):1116–1130. doi: 10.1177/1049732309341728. Available from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1049732309341728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan WD, Lepore SJ. Searching for and making meaning after breast cancer: Prevalence, patterns, and negative affect. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(6):1176–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.038. Epub ahead of print Jan 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Knobf MT. Clinical update: Psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2011;27(3):e1–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal I, Engebretson J, Cohen L, et al. Experiences of paradox: A qualitative analysis of living with cancer using a framework approach. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(2):138–146. doi: 10.1002/pon.3578. Epub ahead of print May 16, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, et al. Clarifying “meaning” in the context of cancer research: A systematic literature review. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2004;2(3):291–303. doi: 10.1017/s1478951504040386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Anderson B, editors. Psychological Interventions for Cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Milbury K, Spelman A, Wood C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of expressive writing for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(7):663–670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3532. Epub ahead of print Jan 27. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3927735/pdf/zlj663.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moch SD. Health within illness: Conceptual evolution and practice possibilities. ANS: Advances in Nursing Science. 1989;11(4):23–31. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1(2):115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluative Methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs E, Kolva E, Pessin H, et al. On sinking and swimming: The dialectic of hope, hopelessness, and acceptance in terminal cancer. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2013;30(2):121–127. doi: 10.1177/1049909112445371. Epub ahead of print May 2, 2012. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4972334/pdf/nihms805351.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JE, Andrykowski MA. The role of social and dispositional variables associated with emotional processing in adjustment to breast cancer: An internet-based study. Health Psychology. 2004;23(3):259–266. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg SS. Vitality and growth in HIV-infected gay men. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(4):593–602. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Bower JE, Low CA. Post-traumatic growth after cancer. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of Post-Traumatic Growth: Research and Practice. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 138–175. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ. Transformation of tragedy among women surviving breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2000;27(5):781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Expert companions: Posttraumatic growth in clinical practice. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of Post-Traumatic Growth: Research and Practice. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23(1):16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckett AG. Applying thematic analysis theory to practice: A researcher’s experience. Contemporary Nurse. 2005;19(1–2):75–87. doi: 10.5172/conu.19.1-2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman AD, Worden JW. The existential plight in cancer: Significance of the first 100 days. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1977;7(1):1–15. doi: 10.2190/uq2g-ugv1-3ppc-6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora JR, Blanchard CG, Smith ED, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1997;15(2):73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner T, Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology: A critical review and introduction of a two-component model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(5):626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. Epub ahead of print Mar 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]