Abstract

Mounting evidence supports an important role of chemokines, produced by spinal cord astrocytes, in promoting central sensitization and chronic pain. In particular, CCL2 (C–C motif chemokine ligand 2) has been shown to enhance N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced currents in spinal outer lamina II (IIo) neurons. However, the exact molecular, synaptic, and cellular mechanisms by which CCL2 modulates central sensitization are still unclear. We found that spinal injection of the CCR2 antagonist RS504393 attenuated CCL2- and inflammation-induced hyperalgesia. Single-cell RT-PCR revealed CCR2 expression in excitatory vesicular glutamate transporter subtype 2-positive (VGLUT2+) neurons. CCL2 increased NMDA-induced currents in CCR2+/VGLUT2+ neurons in lamina IIo; it also enhanced the synaptic NMDA currents evoked by dorsal root stimulation; and furthermore, it increased the total and synaptic NMDA currents in somatostatin-expressing excitatory neurons. Finally, intrathecal RS504393 reversed the long-term potentiation evoked in the spinal cord by C-fiber stimulation. Our findings suggest that CCL2 directly modulates synaptic plasticity in CCR2-expressing excitatory neurons in spinal lamina IIo, and this underlies the generation of central sensitization in pathological pain.

Keywords: Chemokines, C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), Neuron–glial interaction

Introduction

Chemokines are a family of small, functionally-related secreted molecules that play important roles in the pathogenesis of chronic pain via peripheral and central mechanisms [1–7]. C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, is the best studied chemokine in pain modulation. Although it recognizes several receptors, its receptor CCR2 is preferred [8, 9]. Mice lacking CCR2 display a substantial reduction in mechanical allodynia after partial ligation of the sciatic nerve [10, 11]. Nerve injury induces the upregulation of CCL2 in primary sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [12, 13], and CCL2 induces peripheral sensitization in DRG nociceptive neurons via CCR2 [12]. Sensory neuron-derived CCL2 has also been implicated in the activation of monocytes in the DRG [14] and microglia in the spinal cord [15, 16] in neuropathic pain.

Accumulating evidence indicates that chemokines in the central nervous system play a pivotal role in neuron–glial interactions in chronic pain [2, 6, 17]. Chemokines not only regulate neuron-microglial interactions [15, 16, 18–20], but also neuron-astroglial interactions in the spinal cord [21–23]. Our previous study has shown that nerve injury also induces CCL2 expression in spinal cord astrocytes, and this is critical for the maintenance of neuropathic pain [23]. In the spinal cord, CCL2 serves as a neuromodulator and induces central sensitization via activation of extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK), leading to enhanced N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) currents in spinal lamina II neurons [23].

However, the exact molecular, synaptic, and cellular mechanisms by which CCL2 modulates central sensitization remain unclear. There are several outstanding questions. (1) Does CCL2 directly act on neurons to modulate central sensitization? (2) Is CCR2 critical for the mediation of CCL2-induced central sensitization? (3) Does CCL2 modulate central sensitization in excitatory neurons? (4) Can CCL2 modulate NMDA receptor (NMDAR) activity at nociceptive synapses? (5) Can CCL2/CCR2 modulate long-term synaptic plasticity in the spinal cord? The present study was designed to address these questions using behavioral, pharmacological, and electrophysiological approaches. In particular, we combined single-cell PCR and patch-clamp recording to determine the cellular mechanism by which CCL2 regulates NMDAR function. Our findings showed that CCL2 acts directly on CCR2-expressing excitatory neurons to enhance NMDA-induced currents.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and Pain Models

C57BL/6 background WT control mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and bred in the Animal Facility of Duke Medical Center. Spinal cord slices from young mice of both sexes (4–6 weeks old) were used to obtain high-quality electrophysiological recordings. Of note, spinal pain circuits are well-developed by 2 weeks postnatally [24]. We also used transgenic C57BL/6 mice (5 weeks old) for some electrophysiological experiments. These transgenic mice, from the Jackson Laboratory, express tdTomato fluorescence in somatostatin-positive (SOM+) neurons, after Som-Cre mice were crossed with tdTomato Cre-reporter mice (Rosa26-floxed stop tdTomato mice, Jackson Laboratory), to generate conditional transgenic mice that express tdTomato in SOM+ neurons [25]. Adult CD1 mice (male, 8–10 weeks old) were used for behavioral and pharmacological studies. All the animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Duke Medical School. To induce persistent inflammatory pain, complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA, 20 μL, 1 mg/mL, Sigma) was injected into the plantar surface of a hind paw.

Drugs and Administration

RS504393, a potent and selective antagonist of CCR2, was from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). CCL2 was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). For intrathecal injection, under brief anesthesia with isoflurane a lumbar puncture was made at L5–L6 with a 30-gauge needle [20].

Behavioral Analysis

Animals were habituated to the testing environment daily for at least 2 days before baseline testing. Animals were put in plastic boxes for 30 min habituation before examination. Heat sensitivity was tested by radiant heat using Hargreaves [26] apparatus (IITC Life Science Inc.) and expressed as paw withdrawal latency (PWL). The PWLs were adjusted to 9–12 s, with a cutoff of 20 s to prevent tissue damage. The experimenters were blinded to treatments.

Spinal Cord Slice Preparation and Patch-Clamp Recordings

We prepared spinal slices as previously reported [27]. A portion of the lumbar cord (L4–L5) was removed from mice under urethane anesthesia (1.5–2.0 g/kg, i.p.) and kept in pre-oxygenated ice-cold Krebs’ solution. We cut transverse slices (450 μm) on a vibrating microslicer and perfused the slices with Krebs’ solution (8–10 mL/min) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 36 ±1°C for at least 1–3 h before experiments. The Krebs’ solution consists of (in mmol/L): 117 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 11 glucose. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from outer lamina II (IIo) neurons in voltage-clamp mode. Patch pipettes were fabricated from thin-walled borosilicate and glass-capillary tubing with an outer diameter of 1.5 mm (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and resistance of 5–10 MΩ.

To measure evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) in lamina IIo neurons, we stimulated the dorsal root entry zone via a concentric bipolar electrode using an isolated current stimulator [28]. The internal solution contained (in mmol/L): 110 Cs2SO4, 0.1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 5 ATP-Mg. After establishing the whole-cell configuration, neurons were held at the potential of −70 mV to record eEPSCs. QX-314 (5 mmol/L) was added to the pipette solution to prevent discharge of action potentials. Test pulses of 0.1 ms at 0.5–3 mA were given at 30-s intervals to record monosynaptic C-fiber responses. The responses were considered to be monosynaptic if (1) the latency remained constant and (2) there was no failure during stimulation at 20 Hz for 1 s, or failures did not occur during repetitive stimulation (2 Hz, 10 s) [29, 30]. Synaptic strength was quantified by the peak amplitudes of eEPSCs. The spinal slice was kept in the holding chamber for >1 h and then transferred to a recording chamber containing normal Mg2+-free artificial cerebrospinal fluid with 2 μmol/L CNQX, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 22°C. After establishing the whole-cell configuration, neurons were held at +40 mV to record NMDAR-mediated eEPSCs [31]. Total NMDA currents were also recorded in lamina IIo neurons by perfusion with NMDA (50 μmol/L, 30 s). Membrane currents were amplified with an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) in voltage-clamp mode, and signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Data were stored and analyzed using pCLAMP10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Spinal Cord LTP Recordings in Anesthetized Mice

Mice were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) for in vivo electrophysiology. In order to maintain electrolyte balance, phosphate-buffered saline (0.5–1 mL, i.p.) was injected before surgery and then every 2 h after surgery. A laminectomy was performed at vertebrae T13-L1 to expose the lumbar enlargement for spinal recording. The vertebral column was firmly suspended by rostral and caudal clamps on a stereotaxic frame. The left sciatic nerve was exposed for bipolar electrical stimulation. The exposed cord and sciatic nerve were covered with paraffin oil. Colorectal temperature was kept at 37–38°C with a feedback-controlled heating blanket. Field potentials were recorded in the ipsilateral L4–L5 segments with glass microelectrodes, 100–300 μm below the surface of the cord, following electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve. In vivo long-term potentiation (LTP) was recorded as previously reported [34, 35]. After obtaining stable responses to test stimuli (0.5 ms every 5 min for >40 min, at 2× the C-fiber threshold), we induced LTP of C-fiber-evoked field potentials by applying conditioning tetanic stimuli to the sciatic nerve (5× C-fiber threshold, 100 Hz, 1 s duration, 4 trains at 10-s intervals). The CCR2 antagonist was delivered intrathecally through a PE5 catheter inserted at the L5–L6 level via lumbar puncture.

Single-Cell Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Single-cell RT-PCR was conducted as previously reported [30]. Briefly, after whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in spinal cord slices, lamina IIo neurons were harvested into patch pipettes (tip diameter, 15–25 μm). The cells were carefully put into reaction tubes containing reverse transcription reagents and incubated for 1 h at 50°C (SuperScript III, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). We used the cDNA products in separate PCR reactions. We conducted the first round of PCR in 50 μL PCR buffer containing 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs, 0.2 μmol/L “outer” primers, 5 μL RT product, and 0.2 μL platinum TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The protocol included an initial 5-min denaturizing step at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 40 s denaturation at 95°C, 40 s annealing at 55°C, and 40 s elongation at 72°C. The reaction was completed with 7 min of final elongation. For the second round of amplification, the reaction buffer (20 μL) contained 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs, 0.2 μmol/L “inner” primers, 5 μL of the first round PCR products and 0.1 μL platinum TaqDNA polymerase. The amplification procedure for the inner primers was the same as that of the first round. A negative control was also included by putting pipettes that did not contain cells in the bath solution. The PCR products were displayed on 1% ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. The sequences for all the inner and outer primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of primer sequences used for RT-PCR.

| Target gene (product length)a | Outer primers | Inner primers | G enbank No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH (367, 313 bp) | Forward | AGCCTCGTCCCGTAGACAAAA | TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGAATT | XM_001473623.1 |

| Reverse | TTTTGGCTCCACCCCTTCA | GCTTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGA | ||

| vGluT2 (267, 199 bp) | Forward | TCATTGCTGCACTCGTCCACT | TTGCCTCAGGAGAGAAACAACC | NM_080853.3 |

| Reverse | GCGCACCTTCTTGCACAAA | TCTTCCTTTTTCTCCCAGCCG | ||

| VIAAT (560, 468 bp) | Forward | GCTGGTGATGACGTGTATCTT | GTATCTTGTACGTCGTGGTGAG | NM_009508.2 |

| Reverse | CGAAGAAGGGCAACGGATAG | GGTTATCCGTGATGACTTCCTT | ||

| CCR2 (456, 214 bp) | Forward | CTGCTCTTCCTGCTCACATTAC | AGCCAGGACAGTTACCTTTG | NM_009915.2 |

| Reverse | CCTGTGCCTCTTCTTCTCATTC | GCAGATGACCATGACAAGTAGA | ||

aNumbers in parentheses indicate sizes of PCR products obtained from outer and inner primers, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We collected the recording data before and after drug treatment for statistical analysis using paired or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test [34]. LTP data were tested using two-way ANOVA [29]. Behavioral data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by the post-hoc Bonferroni test. The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

CCR2 Mediates CCL2- and CFA-Induced Heat Hyperalgesia

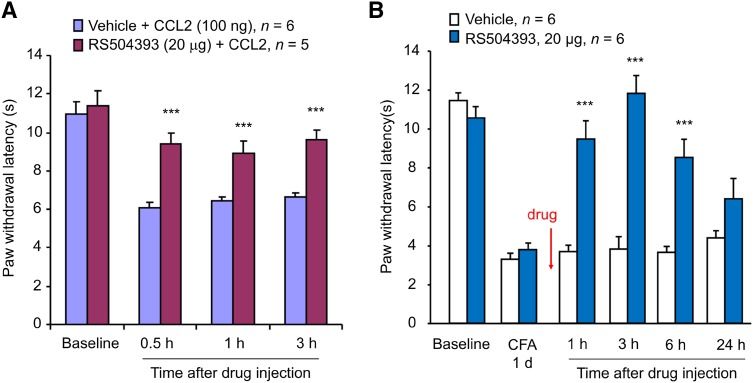

To investigate the mechanisms by which CCL2 elicits central sensitization, we tested the involvement of spinal CCR2 in CCL2- and CFA-induced hyperalgesia. As we previously reported [23], intrathecal CCL2 (100 ng) induced rapid heat hyperalgesia (Fig. 1A). Intraplantar CFA injection induced marked heat hyperalgesia on day 1 (Fig. 1B). Notably, this heat hyperalgesia was completely reversed by RS504393 (20 μg, i.t.) at 3 h after injection (Fig. 1B). This reversal was also transient and recovered 6 h after antagonist treatment (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that CCR2 is required to mediate both CCL2- and inflammation-induced heat hyperalgesia.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of CCL2- and CFA-induced heat hyperalgesia by intrathecal injection of RS504393. A Prevention of CCL2 (100 ng, i.t)-induced heat hyperalgesia by RS504393 (20 μg, i.t.). B Reversal of CFA-induced heat hyperalgesia by RS504393 (20 μg, i.t.) given 1 day after CFA injection. ***P < 0.001 vs vehicle control (10% DMSO), two-Way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Bonferroni test; n = 5–6 mice/group; data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

CCL2 Enhances NMDA Currents in CCR2-Expressing Excitatory Neurons in Spinal Cord Slices

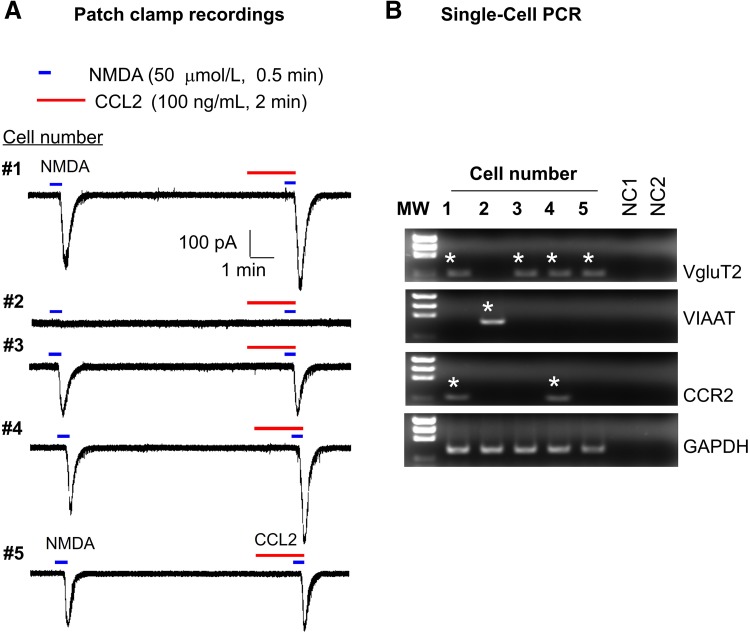

CCL2 is known to induce central sensitization via enhancing the NMDA-induced currents in lamina IIo neurons in spinal cord slices [23]. However, it is unclear if these lamina IIo neurons are excitatory, although most are [35]. We combined patch-clamp recording (Fig. 2A) and single-cell PCR (Fig. 2B) to define whether the neurons we recorded are excitatory, using vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2) as a marker. To improve the sensitivity and selectivity of single-cell PCR, we performed two rounds of PCR using two sets of primers (outer and inner primers, Table 1), and found that 4 out of 5 lamina IIo neurons expressed VGLUT2, while the negative control showed no signal (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the VGLUT2-negative neurons expressed vesicular inhibitory amino-acid transporter (VIAAT), a marker of inhibitory neurons (Fig. 2B). Patch-clamp recording revealed that all the VGLUT2+ neurons but not VIAAT+ neurons had NMDA-induced currents (Fig. 2A). Moreover, CCL2 treatment showed increased NMDA currents in 2 of 5 neurons (Fig. 2A). Consistently, only these CCL2-responsive neurons expressed CCR2 (Fig. 2B). Together, the findings from this experiment suggest that CCL2 acts directly on CCR2+ excitatory neurons to regulate central sensitization via postsynaptic NMDARs.

Fig. 2.

A combination approach of patch-clamp recordings and single-cell PCR showed enhancement of NMDA currents by CCL2 in CCR2-expressing excitatory neurons in lamina IIo neurons of spinal cord slices. A Patch-clamp recording shows NMDA (50 μmol/L)-induced currents in lamina IIo neurons and the effect of CCL2 (100 ng/mL). CCL2 treatment increased NMDA currents in 2 of 5 neurons. B Single-cell PCR from the recorded neurons demonstrated that 4 out of 5 lamina IIo neurons expressed VGLUT2. GAPDH was used as positive control. Negative control (NC), no cells in the reaction buffer. Positive bands are indicated by stars. Note that only two CCR2-expressing neurons displayed increased NMDA currents after the CCL2 treatment. Also note that all the VGLUT2+ but not the VIAAT+ neurons exhibited NMDA currents.

CCL2 Enhances NMDA Currents in Somatostatin-Expressing Dorsal Horn Neurons

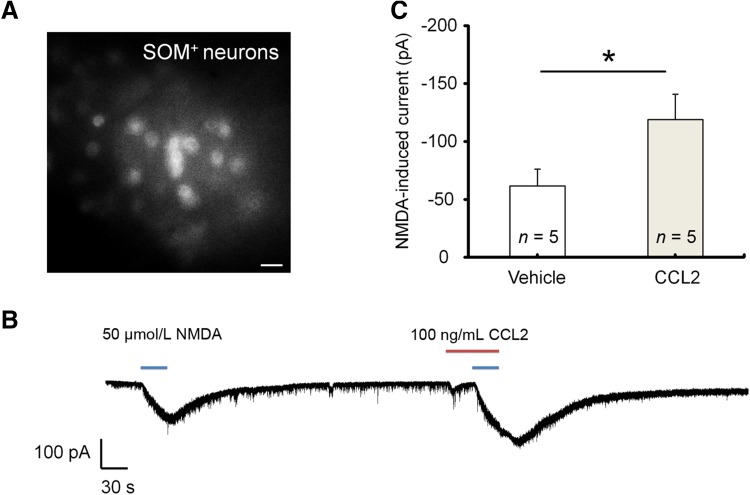

Spinal cord lamina IIo neurons are predominantly excitatory [36] and form a nociceptive circuit: they receive input from C-fiber afferents and send output to lamina I projection neurons [37, 38]. These excitatory interneurons express somatostatin (SOM) [39]. We also recorded CCL2 responses in SOM+ neurons in lamina IIo of spinal slices from transgenic mice showing SOM expression with tdTomato [25]. These neurons were easily identified by bright fluorescence (Fig. 3A). CCL2 perfusion caused a marked increase in NMDA currents in all 5 lamina IIo SOM+ neurons recorded (Fig. 3B, C). This result further supports the hypothesis that CCL2 facilitates NMDAR function in excitatory neurons in the pain circuit.

Fig. 3.

CCL2 enhances NMDA currents in SOM+ neurons in lamina IIo of spinal cord slices. A SOM+ neurons in lamina IIo of spinal cord slices from transgenic mice, as shown by tdTomato fluorescence (scale bar, 20 μm). B Traces of NMDA-induced currents in SOM+ neurons before and after CCL2 perfusion. C Amplitude of NMDA-induced currents. *P < 0.05, paired two-tailed Student’s t test; n = 5 neurons/group; data expressed as mean ± SEM.

CCL2 Enhances Synaptic NMDA Currents Evoked by Dorsal Root Stimulation

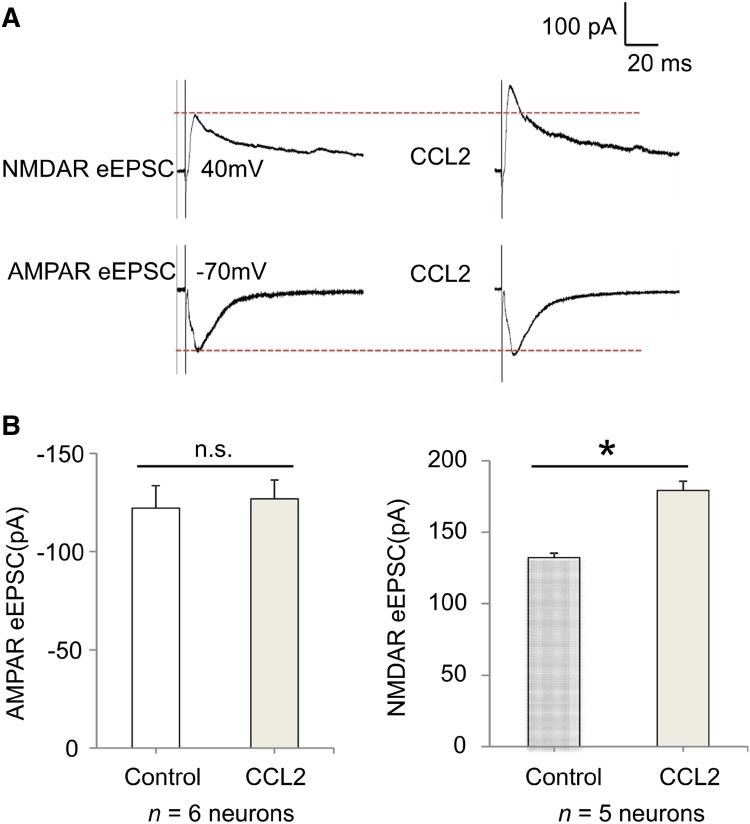

To further assess if CCL2 can modulate excitatory synaptic transmission at nociceptive synapses, we recorded α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and NMDA currents evoked by dorsal root stimulation at C-fiber intensity. Test pulses of 0.1 ms at 0.5–3 mA were delivered at 30-s intervals and monosynaptic C-fiber responses were recorded as previously reported [31]. At a holding potential of +40 mV, stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone in the presence of the AMPAR antagonist CNQX isolated NMDAR-mediated evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) in lamina IIo neurons, and these eEPSCs were enhanced by CCL2 superfusion for 2 min (Fig. 4A, B). We also recorded AMPAR-induced eEPSCs in lamina IIo neurons by holding cells at −70 mV and blocking the NMDARs with APV. Notably, CCL2 did not increase the AMPAR-induced eEPSCs (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 4.

CCL2 enhances NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents in lamina IIo neurons evoked by dorsal root stimulation of spinal cord slices. A Traces of evoked NMDAR-mediated and AMPAR-mediated currents (eEPSC) before and after CCL2 treatment (100 ng/mL, 2 min). B Amplitude of NMDAR-mediated and AMPAR-mediated currents (eEPSC). *P < 0.05, paired two-tailed Student’s t test; n = 5–6 neurons/group; n.s., not significant. Note that CCL2 only enhanced NMDAR-mediated but not AMPAR-mediated synaptic currents. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

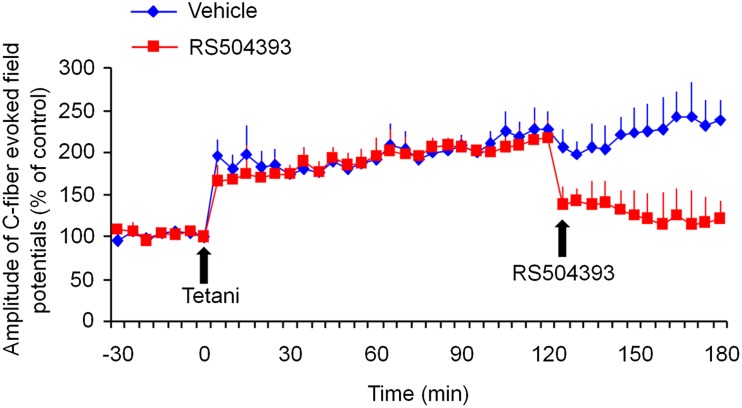

CCR2 Antagonist RS504393 Reverses Spinal LTP in vivo

LTP in the dorsal horn is a unique form of synaptic plasticity in the spinal pain circuit and has been strongly implicated in the genesis of chronic pain [40–42]. In anesthetized mice, spinal LTP was induced by tetanic stimulation (100 Hz, 1 s, 4 trains) in all C57/B6 WT mice; it lasted for >3 h, with an amplitude increase of >100% at 1 h (Fig. 5). Strikingly, a single intrathecal administration of RS504393 (45 μg/15 μL) at 2 h after the induction of LTP was still able to rapidly reverse the established spinal LTP (Fig. 5). This result supports a critical role of CCR2 in the maintenance of spinal LTP.

Fig. 5.

Reversal of LTP of C-fiber-evoked field potentials in the dorsal horn of anesthetized mice by RS504393 (45 μg, 15 μL, i.t.), administered 2 h after LTP induction. Spinal LTP was induced by tetanic stimulation (100 Hz, 1 s, 4 trains) of C-fiber intensity in C57/B6 mice. *P < 0.05, vehicle (10% DMSO) vs RS504393, two-way ANOVA, n = 5 mice/group.

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that chemokines play a critical role in neuron–glial interactions in chronic pain [2]. However, it is incompletely known how chemokines control the interactions between neurons and glia. Early studies showed that primary sensory neuron-derived CCL2 activates spinal microglia [15, 16, 43], suggesting an active role of chemokines in the neuron-to-glia interaction. However, CCR2 is mainly expressed by macrophages but not microglia [44]. An in situ hybridization study demonstrated that CCR2 is primarily expressed by neurons in the dorsal horn [23]. Since CCL2 is induced in spinal astrocytes after nerve injury, we proposed a novel role of CCL2 to mediate glia-to-neuron interaction and identified CCL2 as a neuromodulator in the spinal cord [23]. However, the exact molecular, synaptic, and cellular mechanisms by which CCL2 drives central sensitization are still unclear.

In this study, we have provided new mechanistic insights into the CCL2 regulation of neuronal and synaptic plasticity underlying the generation of central sensitization [41, 45]. First, CCL2 appears to have a direct action on dorsal horn neurons to modulate central sensitization. Second, CCR2 is required to mediate CCL2-induced central sensitization such as spinal CCL2-induced heat hyperalgesia. Third, CCL2 induces central sensitization in VGLUT2+ and SOM+ excitatory neurons via CCR2. Fourth, CCL2 increases NMDAR-mediated but not AMPAR-mediated eEPSCs at nociceptive synapses. Finally, CCR2 is necessary for the maintenance of spinal LTP in vivo.

By combining patch clamp recording and single-cell PCR in the recorded neurons, our findings showed that CCL2 increased NMDA-induced currents exclusively in CCR2-positive excitatory neurons that express VGLUT2 but not VIAAT. We also confirmed that CCL2 facilitates NMDA currents in SOM+ excitatory interneurons. This population of interneurons is essential for pain transmission and forms a nociceptive circuit by receiving input from TRPV1 (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1)-expressing C-fiber afferents and sending output to lamina I projection neurons [35, 46, 47]. It is likely that CCL2 increases NMDAR activity via the phosphorylation of ERK [23, 48], a marker for central sensitization [49, 50]. Further study is needed to determine how CCL2 facilitates NMDARs via the CCR2/ERK pathway. In addition to heat hyperalgesia (Fig. 1), this pathway may also regulate mechanical allodynia [23].

Our data also demonstrated that CCL2 enhanced NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents evoked by dorsal root stimulation. This effect could be mediated by both presynaptic and postsynaptic modulation of NMDARs by CCL2/CCR2. Presynaptic NMDARs have been implicated in pain hypersensitivity [31, 51] (but also see [52]). Although we did not find potentiation of AMPAR-mediated synaptic currents by CCL2, application of CCL2 to spinal slices increased the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs in lamina IIo neurons of the dorsal horn [23], suggesting a possible presynaptic mechanism by which CCL2 enhances glutamate release. Further recordings of miniature EPSCs may provide new insights into the presynaptic modulation of AMPARs.

One of the most exciting findings of this study was reversal of the C-fiber stimulation-induced spinal LTP by the CCR2 antagonist RS504393, even when applied 2 h after the induction of LTP. This result suggests a critical involvement of CCL2/CCR2 in the maintenance of spinal LTP. A recent study has illustrated a new type of spinal LTP induced by spinal glial cells [53]. It appears that activation of spinal glia by the ATP receptor P2X7 is both sufficient and necessary for the induction of spinal LTP. Furthermore, this gliogenic LTP is diffusible [53]. Since CCL2 is mainly derived from astrocytes, especially under pathological conditions, it is of great interest to investigate whether activation of P2X7 in astrocytes can induce spinal LTP via triggering CCL2 release.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31400949, 81502102, 31471059, 81371498, and 31371121) and NIH R01, USA Grants (DE17794, DE22743, and NS87988).

Contributor Information

Rou-Gang Xie, Email: rgxie@fmmu.edu.cn.

Ru-Rong Ji, Email: ru-rong.ji@duke.edu.

References

- 1.White FA, Jung H, Miller RJ. Chemokines and the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20151–20158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709250104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao YJ, Ji RR. Chemokines, neuronal-glial interactions, and central processing of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai L, Wang X, Li Z, Kong C, Zhao Y, Qian JL, et al. Upregulation of Chemokine CXCL12 in the Dorsal Root Ganglia and Spinal Cord Contributes to the Development and Maintenance of Neuropathic Pain Following Spared Nerve Injury in Rats. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s12264-015-0007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhangoo SK, Ren D, Miller RJ, Chan DM, Ripsch MS, Weiss C, et al. CXCR4 chemokine receptor signaling mediates pain hypersensitivity in association with antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbadie C, Bhangoo S, De KY, Malcangio M, Melik-Parsadaniantz S, White FA. Chemokines and pain mechanisms. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo W, Wang H, Zou S, Dubner R, Ren K. Chemokine signaling involving chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 plays a role in descending pain facilitation. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1218-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong F, Du YR, Xie W, Strong JA, He XJ, Zhang JM. Increased function of the TRPV1 channel in small sensory neurons after local inflammation or in vitro exposure to the pro-inflammatory cytokine GRO/KC. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1208-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurihara T, Bravo R. Cloning and functional expression of mCCR2, a murine receptor for the C-C chemokines JE and FIC. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11603–11607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung H, Bhangoo S, Banisadr G, Freitag C, Ren D, White FA, et al. Visualization of chemokine receptor activation in transgenic mice reveals peripheral activation of CCR2 receptors in states of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8051–8062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0485-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Shi XQ, Echeverry S, Mogil JS, De Koninck Y, Rivest S. Expression of CCR2 in both resident and bone marrow-derived microglia plays a critical role in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12396–12406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3016-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbadie C, Lindia JA, Cumiskey AM, Peterson LB, Mudgett JS, Bayne EK, et al. Impaired neuropathic pain responses in mice lacking the chemokine receptor CCR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7947–7952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331358100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White FA, Sun J, Waters SM, Ma C, Ren D, Ripsch M, et al. Excitatory monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signaling is up-regulated in sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14092–14097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503496102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, De Koninck Y. Spatial and temporal relationship between monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and spinal glial activation following peripheral nerve injury. J Neurochem. 2006;97:772–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu XJ, Liu T, Chen G, Wang B, Yu XL, Yin C, et al. TLR signaling adaptor protein MyD88 in primary sensory neurons contributes to persistent inflammatory and neuropathic pain and neuroinflammation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28188. doi: 10.1038/srep28188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Shi XQ, Echeverry S, Mogil JS, De Koninck Y, Rivest S. Expression of CCR2 in both resident and bone marrow-derived microglia plays a critical role in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12396–12406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3016-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thacker MA, Clark AK, Bishop T, Grist J, Yip PK, Moon LD, et al. CCL2 is a key mediator of microglia activation in neuropathic pain states. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji RR, Xu ZZ, Gao YJ. Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:533–548. doi: 10.1038/nrd4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyomitsu E, Tsuda M, Yamashita T, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Tanaka Y, Inoue K. CCL2 promotes P2X4 receptor trafficking to the cell surface of microglia. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9288-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark AK, Yip PK, Malcangio M. The liberation of fractalkine in the dorsal horn requires microglial cathepsin S. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6945–6954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0828-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuang ZY, Kawasaki Y, Tan PH, Wen YR, Huang J, Ji RR. Role of the CX3CR1/p38 MAPK pathway in spinal microglia for the development of neuropathic pain following nerve injury-induced cleavage of fractalkine. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang BC, Cao DL, Zhang X, Zhang ZJ, He LN, Li CH, et al. CXCL13 drives spinal astrocyte activation and neuropathic pain via CXCR5. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:745–761. doi: 10.1172/JCI81950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen G, Park CK, Xie RG, Berta T, Nedergaard M, Ji RR. Connexin-43 induces chemokine release from spinal cord astrocytes to maintain late-phase neuropathic pain in mice. Brain. 2014;137:2193–2209. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao YJ, Zhang L, Samad OA, Suter MR, Yasuhiko K, Xu ZZ, et al. JNK-induced MCP-1 production in spinal cord astrocytes contributes to central sensitization and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4096–4108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3623-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgerald M. The development of nociceptive circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:507–520. doi: 10.1038/nrn1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu CC, Gao YJ, Luo H, Berta T, Xu ZZ, Ji RR, et al. Interferon alpha inhibits spinal cord synaptic and nociceptive transmission via neuronal-glial interactions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34356. doi: 10.1038/srep34356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Berta T, Xu ZZ, Liu T, Park JY, Ji RR. TNF-alpha contributes to spinal cord synaptic plasticity and inflammatory pain: distinct role of TNF receptor subtypes 1 and 2. Pain. 2011;152:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berta T, Park CK, Xu ZZ, Xie RG, Liu T, Lu N, et al. Extracellular caspase-6 drives murine inflammatory pain via microglial TNF-alpha secretion. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1173–1186. doi: 10.1172/JCI72230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T, Berta T, Xu ZZ, Park CK, Zhang L, Lu N, et al. TLR3 deficiency impairs spinal cord synaptic transmission, central sensitization, and pruritus in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2195–2207. doi: 10.1172/JCI45414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo C, Kumamoto E, Furue H, Chen J, Yoshimura M. Nociceptin inhibits excitatory but not inhibitory transmission to substantia gelatinosa neurones of adult rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2002;109:349–358. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen G, Xie RG, Gao YJ, Xu ZZ, Zhao LX, Bang S, et al. beta-arrestin-2 regulates NMDA receptor function in spinal lamina II neurons and duration of persistent pain. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12531. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu YX, Zhang Y, Zhang YQ, Zhao ZQ. Involvement of microglial P2X7 receptors and downstream signaling pathways in long-term potentiation of spinal nociceptive responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1176–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu ZZ, Liu XJ, Berta T, Park CK, Lu N, Serhan CN, et al. Neuroprotectin/Protectin D1 protects neuropathic pain in mice after nerve trauma. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:490–495. doi: 10.1002/ana.23928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todd AJ. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasaka T, Tiong SY, Hughes DI, Riddell JS, Todd AJ. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain. 2010;151:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Todd AJ. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Y, Dong H, Gao Y, Gong Y, Ren Y, Gu N, et al. A feed-forward spinal cord glycinergic neural circuit gates mechanical allodynia. J Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4050–4062. doi: 10.1172/JCI70026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan B, Cheng L, Bourane S, Britz O, Padilla C, Garcia-Campmany L, et al. Identification of spinal circuits transmitting and gating mechanical pain. Cell. 2014;159:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruscheweyh R, Wilder-Smith O, Drdla R, Liu XG, Sandkuhler J. Long-term potentiation in spinal nociceptive pathways as a novel target for pain therapy. Mol Pain. 2011;7:20. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo C, Kuner T, Kuner R. Synaptic plasticity in pathological pain. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang HM, Zhou LJ, Hu XD, Hu NW, Zhang T, Liu XG. Acute nerve injury induces long-term potentiation of C-fiber evoked field potentials in spinal dorsal horn of intact rat. Acta Physiol Sin. 2004;56:591–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbadie C, Lindia JA, Cumiskey AM, Peterson LB, Mudgett JS, Bayne EK, et al. Impaired neuropathic pain responses in mice lacking the chemokine receptor CCR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7947–7952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331358100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung H, Bhangoo S, Banisadr G, Freitag C, Ren D, White FA, et al. Visualization of chemokine receptor activation in transgenic mice reveals peripheral activation of CCR2 receptors in states of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8051–8062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0485-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP: do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park CK, Lu N, Xu ZZ, Liu T, Serhan CN, Ji RR. Resolving TRPV1- and TNF-a-mediated spinal cord synaptic plasticity and inflammatory pain with neuroprotectin D1. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15072–15085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2443-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duan B, Cheng L, Bourane S, Britz O, Padilla C, Garcia-Campmany L, et al. Identification of spinal circuits transmitting and gating mechanical pain. Cell. 2014;159:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu ZZ, Zhang L, Liu T, Park JY, Berta T, Yang R, et al. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med. 2010;16(592–597):591p. doi: 10.1038/nm.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji RR, Baba H, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. Nociceptive-specific activation of ERK in spinal neurons contributes to pain hypersensitivity. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1114–1119. doi: 10.1038/16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karim F, Wang CC, Gereau RW. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes 1 and 5 are activators of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling required for inflammatory pain in mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3771–3779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03771.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan X, Jiang E, Gao M, Weng HR. Endogenous activation of presynaptic NMDA receptors enhances glutamate release from the primary afferents in the spinal dorsal horn in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Physiol. 2013;591:2001–2019. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.250522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pagadala P, Park CK, Bang S, Xu ZZ, Xie RG, Liu T, et al. Loss of NR1 Subunit of NMDARs in Primary Sensory Neurons Leads to Hyperexcitability and Pain Hypersensitivity: Involvement of Ca2+-Activated Small Conductance Potassium Channels. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13425–13430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0454-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kronschlager MT, Drdla-Schutting R, Gassner M, Honsek SD, Teuchmann HL, Sandkuhler J. Gliogenic LTP spreads widely in nociceptive pathways. Science. 2016;354:1144–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]