Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a known risk factor for endothelial dysfunction. Murine and human lupus studies have implicated a role for IFNα in vascular abnormalities associated with impaired blood vessel dilation. However, the impact of IFNα on mediators that induce vasodilation and modulate inflammation including endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability are unknown. The objectives of this study were to determine how IFNα promotes endothelial dysfunction in SLE focusing on its regulation of eNOS and NO production in endothelial cells. We demonstrate that IFNα promotes an endothelial dysfunction signature in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), characterized by transcription suppression and mRNA instability of eNOS complemented by upregulation of MCP1 and VCAM1. These changes are associated with interferon-inducible gene expression. IFNα impairs insulin mediated NO production and Altered gene expression resulted from eNOS instability, possibly due to enhanced miR-155 expression. IFNα significantly impaired NO production in insulin stimulated HUVECs. IFNα treatment also lead to enhanced neutrophil adhesion. Our study introduces a novel pathway whereby IFNα serves as a pro-atherogenic mediator through repression of eNOS dependent pathways. This could promote development of endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease in SLE.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multi-organ autoimmune disease that is predominately diagnosed in women during childbearing years. Among young women, SLE is associated with a 50-fold increase in atherosclerotic and coronary artery syndromes not fully explained by conventional risk factors(1–3). To date, neither behavioral modifications nor therapeutic regimens have reduced CVD risk in SLE. Therefore, identification of key SLE-related mediators driving SLE- CVD risk is needed.

While immune dysregulation yielding organ dysfunction is well documented in lupus, the exact pathogenesis of vascular endothelial dysfunction (VED) and subsequent accelerated atherosclerosis is unclear. Although multiple mechanisms contribute to the development of VED, all pathways converge on the diminished activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and loss of nitric oxide (NO) production. NO is an anti-atherogenic gas that regulates blood vessel relaxation, platelet aggregation, leukocyte chemotaxis and leukocyte adhesion. Our group recently demonstrated that genetic deletion of the nos3/eNOS gene in an MRL/lpr mouse model lead to enhanced accumulation of oxidized LDL immune complexes in the vessel wall and the formation of perivascular plaques (4). Enhanced cresentic and necrotic glomerular lesions were also observed in the kidneys of these animals(5). Furthermore, lupus aorta have impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilator responses to the eNOS activator, acetylcholine but, nitric oxide synthase inhibition did not demonstrate a role for diminished NO in the loss of aortic vasodilation(6). Others have shown that NZB/W SLE mice developing hypertension and vascular dysfunction do not display significantly different nos3/eNOS mRNA expression at vascular abnormality onset; however, these animals displayed lower eNOS expression as the disease persisted (7). Unfortunately, the aforementioned study did not examine eNOS activity in SLE mice.

Changes in endothelial-dependent vasodilation and subsequent atherosclerosis are mediated by a host of inflammatory factors including Type I interferons which play a role in the development and progression of SLE. Specifically, the type I interferon signature is associated with SLE disease activity, impaired vascular repair, and increased vascular inflammation(8). Approximately 50% of SLE patients have an interferon-dependent pattern of gene expression (IFN-signature) in their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)(9). In vitro and in vivo studies reveal that Type I interferons are crucial drivers of accelerated atherosclerosis in SLE patients (10–12). Further, Type I interferons may contribute to endothelial dysfunction (13, 14), an early marker of atherosclerosis. Recent observations suggested that the Type I IFN signature gene, protein kinase r (PKR) correlated with reduced flow mediated dilation(13), which may serve as an essential regulator of NO bioavailability in humans.

Genetic ablation of the interferon α/β receptor (IFNAR) in New Zealand black/white (NZB/W) lupus prone animals improved NO-dependent aortic constriction and endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) circulation (15). Moreover, apoE (−/−) IFNAR (−/−) lupus animals displayed improved endothelium dependent relaxation and declines in atherosclerotic plaque development (16). These studies indicate that type I interferons are important in promotion of early endothelial dysfunction and may promote atherosclerosis in SLE.

Collectively, these studies suggest that eNOS may be protective against vascular abnormalities associated with the lupus phenotype. Given the high levels of type I IFN signatures observed in SLE patients and previously identified correlations between type I IFNs and impaired vascular function, we hypothesized that one way that IFNα may contribute to endothelial dysfunction is by impairing eNOS activation and NO production in human endothelial cells. This study supports a role for IFNα in reducing endothelial derived NO production in endothelial cells.

Methods

Patient population

This research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration with approval from the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina. Specimens for this study were stored and collected from study visits that were part of a longitudinal observational cohort study known as the SLE Gullah Health or SLEIGH study initiated in 2002 by Dr. Diane Kamen. A thorough description of the study has previously been reported (17). All patients classified as SLE met four of eleven classification criteria revised in 1997 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) (18). Trained rheumatologists performed patient classification and disease activity measures. All serum separated from the blood of healthy and SLE participants was stored in aliquots at −80°C for future use.

Neutrophil Isolation

Briefly, 20 milliliters of human blood were acquired from healthy volunteers and cells were isolated using Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) using directions provided by the manufacturer. The assay was validated by flow cytometry based on forward scatter and side scatter.

Endothelial Cell Culture

Primary HUVECs from pooled donors were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Endothelial Growth Medium-2 (EGM-2) 5% CO2 at 37°C. HUVECs were subcultured using TryPLE Express dissociation reagent when cells were 70–80% confluent. All experiments were carried out using cells between 3-5 passages.

Real Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT2PCR)

To detect changes in mRNA levels, HUVECs were treated for 0, 1, 6, 12, and 24 hours with various concentrations of rHuIFNα 2a (recombinant human interferon alpha, 2a; PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ), 20% SLE, or control sera. For GSNO (S-nitrosoglutathione) experiments, cells were pretreated with GSNO at 25uM and 250uM concentrations for 3 hours. Cells were then treated with IFN-α for an additional 6 hours and RNA was collected.

Total RNA was extracted using a Trizol (Life Technologies)-RNeasy® kit (Qiagen, Frederick, MD, USA) hybrid protocol as previously described (19) and used to synthesize cDNA (SA Biosciences). For RT-PCR, a CFX96 Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Hercules, CA), was used. Changes in expression of NOS3, CCL2, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, GAPDH, and RPL13A was performed using commercially available primers (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA). The following additional oligonucleotide primers were used: PKR: Forward 5′ CTT CCA TCT GAC TCA GGT TT3′ and Reverse 5′ TGC TTC TGA CGG TAT GTA TTA 3′ and MX1: Forward 5′-TAC CAG GAC TAC GAG ATT G 3′ and Reverse 5′TGC CAG GAA GGT CTA TTA G 3′. The relative expression was calculated using the equation 2−ΔΔCt. The fold change gene expression of interest was calculated based on normalization to GAPDH or RPL13A housekeeping genes. For heteronuclear RNA determination, heteronuclear eNOS RNA was detected using the following primers: forward-5′ACC CTC ACC GCT ACA TC 3′ and reverse 5′ C GGG GAC AGG AAA TAG TTG A 3′. PCR Master Mix (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) was used for PCR. Samples were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel, and bands were quantified using Image J Software (NIH, Bethesda Maryland). Commercially available S26 ribosomal RNA primer was used as the internal control (SAbiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA), and values are reported as the mean and standard deviation of the fold change relative to the levels of unstimulated cells.

For mRNA stability experiments cultured HUVECs were pretreated with Actinomycin D (5 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich) for 2 hours followed by treatment with IFNα (1000 IU/ml) and TNFα (100 ng/ml, control) for 6 and 24 hours and assessed by RT-PCR. β-actin was used as the internal housekeeping control.

microRNA Analysis

Analysis of microRNA 155 Expression was performed using a TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit and the individual TaqMan MicroRNA 155 assay (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA. Expression of mature hsa-miR-155 (assay ID: TM 002623) was determined using by Real time PCR. RNU6B (assay ID:001093) was used as an internal control. MicroRNA-155 inhibitor was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with IFNα (1000 IU/ml) for 6 hours and RNA was isolated to examine changes in NOS3 mRNA expression using RT2PCR.

Immunoblotting

Endothelial cells were treated with IFNα (1000 IU/ml) at various time points and/or recombinant Hu-insulin (Sigma Aldrich) 100nM for 15 minutes following IFNα pretreatment. Whole cell extracts were generated using RIPA lysis buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1mM EGTA, 1mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, okadaic acid (Cayman Chemical), protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling, Danver MA, USA) and total protein was used for immunoblot analysis using antibodies directed against eNOS, eNOS Ser1177, and eNOS Thr495 (BD Biosciences) and β-actin (Cell Signaling, Danver, MA). Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln/Nebraska, USA) were used for signal enhancement, and all blots were visualized with an Odyssey scanner (Li-COR Biosciences). Quantitative analyses of band intensity were performed using Image Studio Software v3.1 (Li-COR Biosciences).

Measurement of Nitric Oxide Production

For real time detection of NO production in HUVECs, 1.2×105 cells were seeded in a 12 well tissue culture plate. Following adherence, cells were serum starved for 6h in endothelial basal media (EBM) containing 0.2% FBS. Cells were stimulated with 1000 IU IFNα (30min, 6 hours, or 24 hours pre-incubation), the eNOS specific inhibitor L-NNA (L-NG-Nitroarginine, 10uM; 30 min pre-incubate), or the NO donor DD1 (3-Bromo-3,4,4-trimethyl-3,4-dihydrodiazete 1,2-dioxide, Tocris Biosciences, Bristol, UK). Cells were loaded with 1uM DAF-FM diacetate (4-Amino-5-Methylamino-2′,7′-Difluorofluorescein Diacetate, Invitrogen, OR, USA), detached with phenol-red free TryPLE™ Express (Invitrogen), and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with the gating on viable cells (assessed using propidium iodide) (20)). Urate was also used as a negative control to rule out detection of NO generated by inducible NOS.

Neutrophil Adhesion Assay

HUVECs were plated at 5.0×104 cells/ml in a 24 well plate (Costar) and allowed to adhere overnight. HUVECs were serum starved for 3h in phenol-red free 0.2% FBS Endothelial Basal media (EBM, Lonza) prior to activation with IFNα for 4 hours. TNF-α (100 ng/ml) was used as the positive control. Neutrophils isolated from healthy human blood as outlined above were labeled with Calcein AM (Life Technologies) at 5×105 cells/ml. Neutrophils were washed prior to co-culturing with HUVECs for 60 minutes after which, non-adherent cells were removed by repeated gentle washing with EBM. Calcein Am fluorescence intensity was measured at 520nM with a FLUOStar Omega microplate reader (Cary, NC), and images were captured using confocal microscopy (Olympus, Center Valley, Pennsylvania).

Measurement of MCP-1

MCP-1 concentrations in HUVEC supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

cGMP Assay

HUVECs were cultured at 5×105 cells per ml and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were treated with various compounds and assayed for cGMP kit using (cGMP EIA Biotrak, GE Healthcare, HK Limited, Buckinghamshire, UK) procedures described by the manufacturer.

siRNA Transfection

PKR, NF-κB, or negative control siRNA were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). HUVECs were plated at 1.0*10ˆ5 cells per well in a six well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then transfected using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24-36 hours, cells were stimulated with IFNα (1000 IU/ml) for 6 hours and RNA was isolated to examine changes in NOS3 mRNA expression using RT2PCR.

Statistical Analysis and Data Handling

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Software (Armonk, NY) or GraphPad Prism Version 6.0f (San Diego, CA). Gaussian distribution was determined using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test and the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Paired and unpaired (where appropriate) Student’s t and nonparametric Mann-Whitney test were used depending on the distribution of the data when data were normalized to control. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-tests where data were normally distributed and Wilcoxon Rank’s Sum with Dunn’s post-test was used to analyze neutrophil adhesion data. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

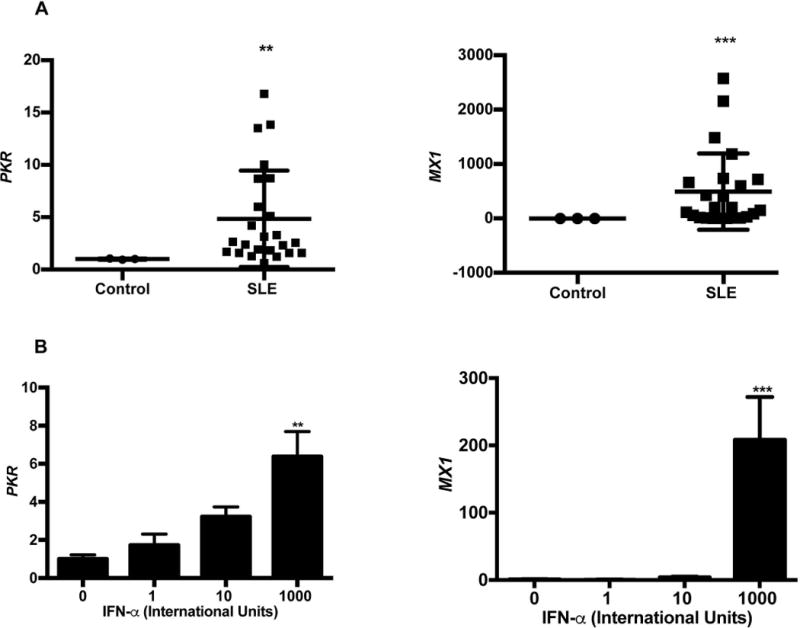

SLE serum induces an IFN-signature

Interferon signature genes (ISGs) are highly abundant in endothelial cells (21) but SLE serum modulation of ISGs has not been examined in HUVECs. We determined that SLE serum profoundly induced ISGs PKR and MX1 relative to healthy control serum in HUVECs (Figure 1A). SLE serum mediated ISG induction was 4.9 and 493.2 fold higher for PKR and MX1, respectively. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells expressed high levels of PKR and MX1 in response to graded concentrations of IFNα (Figure 1B). These findings demonstrated that 1000 IU IFNα treatment induces physiologically relevant levels of PKR and MX1 mRNA expression that mimic serum induction. Thus, 1000 IU IFNα were used for subsequent experiments.

FIGURE 1. SLE serum and IFNα induce type I interferon signature gene expression.

(A) SLE serum enhances human PKR and MX1 expression. HUVECs were treated with 20% serum for 24 hours. Cellular RNA was extracted and gene levels were determined using qRT-PCR. Each scatter plot represents the mean ± SD (n=3 for buffer control, n=24 for SLE patients). (B) IFNα enhances PKR and MX1 expression. HUVECs were treated with 1000 IU/ml IFNα for 24 hours. Gene expression was determined using qRT-PCR. Each bar graph represents the mean ± SD (n=6). Statistical comparisons were performed using a Student’s t-test or One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 and compared to control serum or 0 IU/ml IFNα.

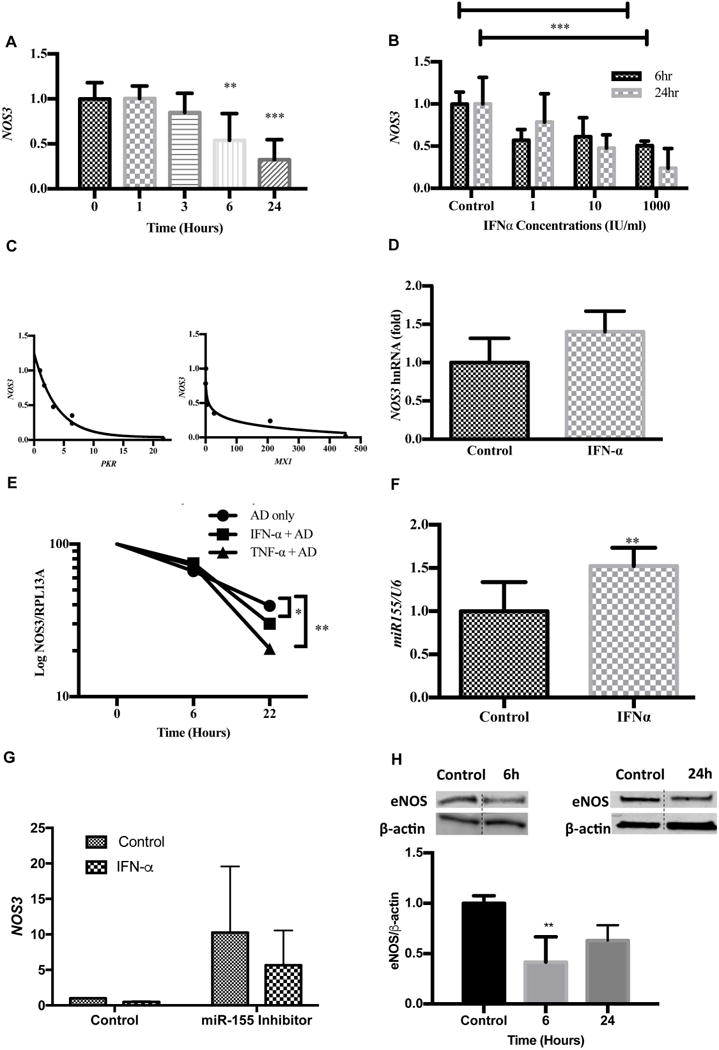

IFNα suppresses NOS3 mRNA in HUVECs

Type I interferons are associated with NO-dependent endothelial dysfunction in SLE(16); yet the molecular underpinnings of these changes are not well understood. We discovered that recombinant IFNα significantly decreases NOS3 mRNA levels in vitro, in a time and dose dependent manner (Figure 2A, B). Specifically, cells exhibited a 50% and 77% decline in NOS3 expression at 6 and 24 hours post-treatment, respectively. Further investigation revealed negative correlations between NOS3 and the measured ISGs, PKR (R2 =0.9855) and MX1 (R2 =0.8555) (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2. Repressed NOS3/eNOS expression may be due to loss of mRNA stability.

(A) IFNα suppresses NOS3 expression in a time dependent manner. HUVECs were treated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml for various time points. RNA was extracted and gene levels were analyzed using qRT-PCR. Each bar graph represents the mean ± SD (n=3). (B) IFNα suppresses NOS3 expression in a dose dependent manner. HUVECs were treated with IFNα at various concentrations for 24 hours. NOS3 expression levels were determined using qRT-PCR. Each bar graph represents the mean ± SD (n=3). (C) NOS3 gene expression negatively correlates with PKR and MX1 induction. HUVECs were stimulated with various concentrations of IFNα (0-1000IU) for 24 hours. NOS3, PKR, MX1, and GAPDH levels were determined using qRT-PCR. Data analysis was performed using a Spearman r correlation test. (D) IFNα does not alter NOS3 heteronuclear RNA. HUVECs were treated with 1000 IU/ml IFNα 24 hours and hnRNA expression was determined using eNOS specific primers. Values are normalized to S26 (n=3). (E) IFNα impairs NOS3 mRNA stability in HUVECs. Cells were incubated with 5ug/ml Actinomycin D for 2 hours to stop transcription. IFNα (1000IU/ml) or negative control (TNFα 100ng/ml) was added at various time points and NOS3 samples were analyzed using qRT-PCR. Statistical analysis was done using the Holm-Sidak method; *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Values are normalized to RPL13A (n=3). (F) IFNα enhances microRNA-155-5p in HUVECs. HUVEC cells were treated with IFNα 1000IU/ml for 6h. MiR-155 expression levels were analyzed using qRT-PCR and values were normalized to U6 (n=3). (G) Knockdown of miR-155 diminishes IFNα effect on NOS3 expression. HUVECs were transfected with miR-155 antisense oligonucleotide or control oligonucleotide and treated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml for 6 hours. RNA isolates were analyzed using qRT-PCR and values were normalized to GAPDH (n=3). (H) Western blots showing endogenous eNOS expression following IFNα stimulation in HUVECs after 6 hours and 24 hours. The eNOS and β-actin bands were spliced together as indicated by the dashed line. Each bar graph represents the mean ± SD (n=6). Statistical comparisons were performed using a Student’s t-test or One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, n=3.

IFNα controls the stability of NOS3 mRNA and eNOS protein expression

NOS3 transcripts are modulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional modifications (22). We demonstrated that heteronuclear RNA levels (hnRNA), which serve as a surrogate measure of transcription rate were unchanged (Figure 2D). However, Actinomycin D studies revealed a significant decrease in NOS3 mRNA half-life at 22h post IFNα and TNFα treatment relative to untreated control cells (Figure 2E). These results suggest the IFNα may underlie observed reductions in NOS3 mRNA. MicroRNA-155 binds the complimentary 7-mer seed sequence in the NOS3 mRNA 3’UTR region, causing instability and accelerated degradation (23). Accordingly, we observed that IFNα significantly induced miR-155 expression in endothelial cells at 1.5± 0.2 fold change relative to control (Figure 2F). This suggest that miR-155 may, in part, account for IFNα mediated effects on NOS3. To further understand the role of miR-155 in IFN-α mediated changes in NOS3 gene expression, we suppressed miR-155 using a miR-155 inhibitor. Our studies showed that in the absence of miR-155, IFNα mediated suppression of NOS3 is reversed. However, these changes were not statistically significant (Figure G). Consistent with this, IFNα reduced eNOS protein expression by 59% and 37% at 6 and 24 hours, respectively (Figure 2H). Thus, IFNα negatively regulated NOS3 mRNA leading to subsequent losses in eNOS protein expression.

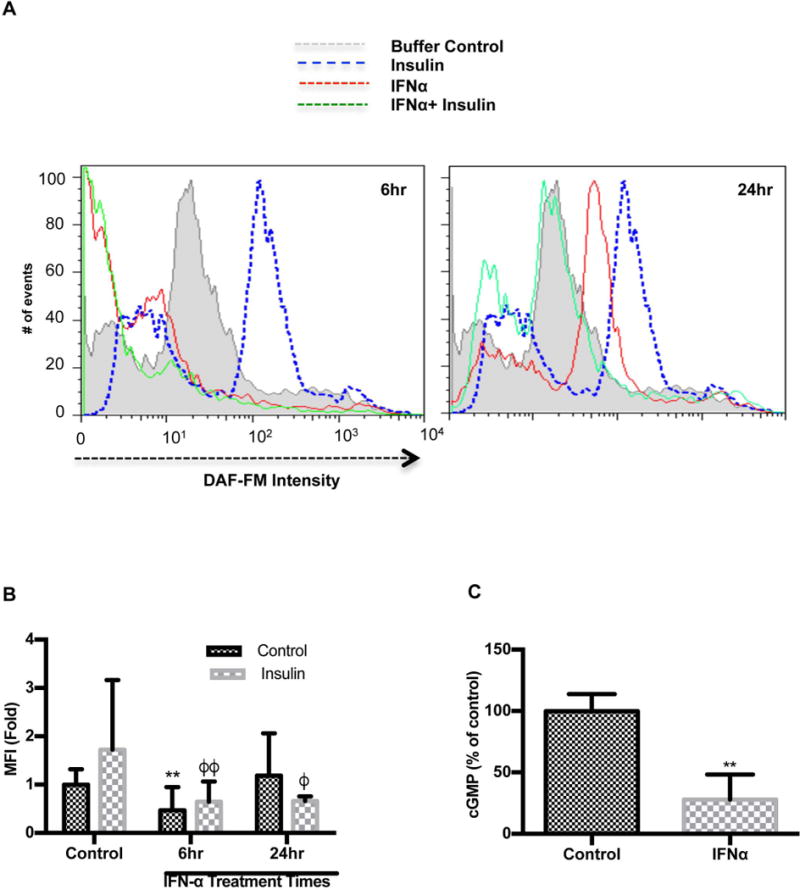

IFNα antagonizes insulin-mediated nitric oxide production

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase produces nanomolar amounts of NO. Coinciding with eNOS protein expression, we detected a 53% reduction in DAF-FM fluorescence intensity after 6 hours IFNα treatment but not at 24 hours. (Figure 3A, B). Insulin is known to be a prominent regulator of eNOS activity and NO production in endothelial cells(24). Thus, it has the ability to increase basal NO production independent of laminar flow. Stimulation with insulin following pretreatment with IFNα demonstrated a profound lowering of insulin-dependent NO production, after 6 (34%) and 24 hours (32%) (Figure 3A, B). One major downstream effect of NO is the activation of guanylyl cyclase. Our studies revealed that IFNα suppressed cGMP which may serve as a functional consequence of declines in NO (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3. IFNα impairs NO and cGMP production in HUVECs.

(A) IFNα impairs NO production in HUVECs. HUVECs were treated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml with or without insulin (100nM). Cells were loaded with DAF-FM diacetate, an NO specific dye. The histogram shows the number of cells with differential DAF-FM diacetate intensity and (B) bar graphs showing DAF-FM diacetate intensity in HUVECs stimulated with buffer (n=3), IFNα for 6 (n=3) or 24h (n=3) ± insulin (n=3). (C) cGMP production in IFNα stimulated HUVECs is reduced. HUVECs were treated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml and cGMP levels were measured as outlined in the materials and methods. (n=3). Statistical comparisons were performed using a Student’s T-test, One-way or Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. The asterisk (*) denotes statistical comparison between the untreated control and other IFNα treated groups. The phi (ϕ) is indicative of statistical comparison between insulin control and other insulin treated cells. **p≤0.01, ϕ p≤0.05 and ϕϕp≤0.01.

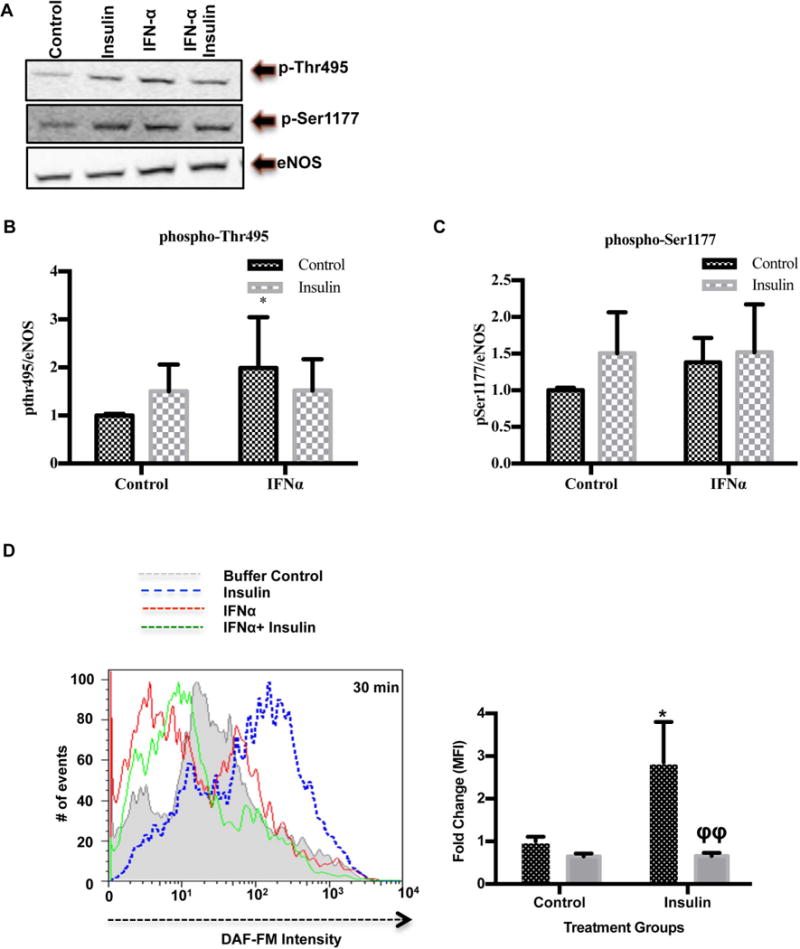

Insulin activates eNOS via phosphorylation at the serine 1177 (Ser1177) site and dephosphorylates at the negative regulatory site, threonine 495 (Thr495) (25). To test if IFN inhibited the phosphorylation of eNOS by insulin, we examined differential expression in eNOS phosphorylation and found that insulin potentiated phosphorylation at the Ser1177 site (insulin: 1.5±0.56 vs. control 1.0±0.033) as well as the Thr495 site (insulin: 1.5±0.34 vs. control 1.00±0.03, p<0.05; Figure 4A, B, C) and phosphorylation at the Thr495 site was significantly increased by IFNα (1.99± 1.06 vs. 1.00±0.03, p<0.05). Although IFNα after 30 minutes didn’t significantly impair NO production, IFNα greatly impaired insulin-mediated NO production by 60% (Figure 4 D). Taken together, these data suggest that IFNα inactivates eNOS via Thr495 phosphorylation in the presence of insulin.

FIGURE 4. IFNα promotes reduced insulin mediated NO production through increased phosphorylation at the eNOS-phosphoThr495 site.

(A) IFNα impairs insulin dependent eNOS ser-1177 phosphorylation in HUVECs. HUVECs were incubated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml for 24 hours and stimulated with insulin (100nM) for 30 minutes. Western blots show endogenous eNOS-Thr495, eNOS-Ser1177, and eNOS following IFNα stimulation ±insulin (n=3). (B) Bar graph showing peNOS-Thr495/β-actin densitometry ratios relative to the untreated control in HUVECs treated with IFNα ± insulin. (C) Bar graph showing peNOS-Ser1177/β-actin densitometry ratios relative to the untreated control in HUVECs treated with IFNα ± insulin. (D) A histogram representing the number of events collected with differential DAF-FM diacetate intensity (surrogate of intracellular NO production) in HUVECs stimulated with IFNα 1000/ml for 30 minutes prior to insulin 100nM stimulation (n=3). Fold change in DAF-FM median fluorescence intensity was quantified as shown in the bar graph. Statistical comparisons were performed using a Student’s T-test or Two-Way ANOVA and Bonferonni’s post-test. The asterisk (*) denotes statistical comparison between the untreated control and other IFNα treated groups. The phi (ϕ) is indicative of statistical comparison between insulin control and other insulin treated cells. *p≤0.05 and ϕϕp≤0.01.

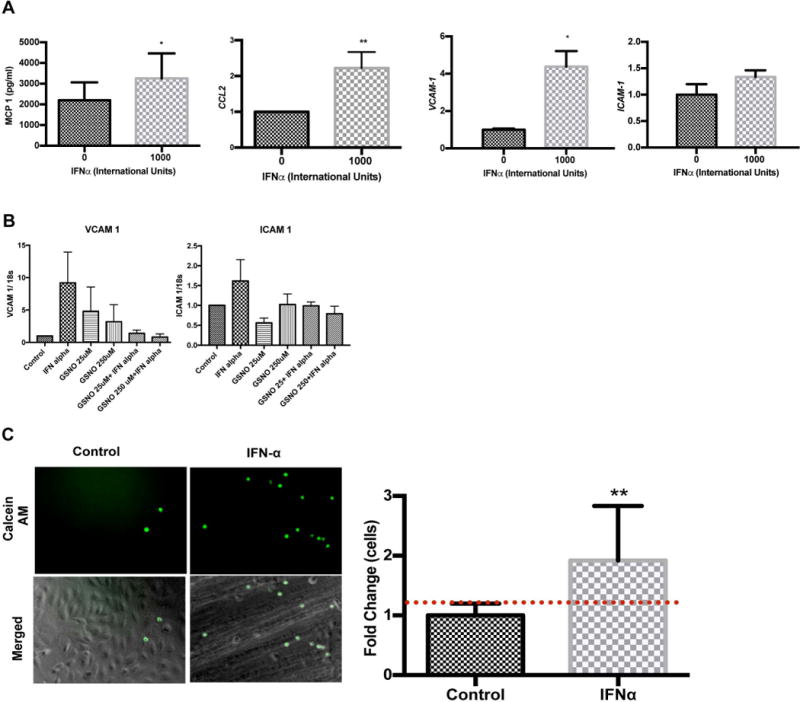

IFNα enhances adhesion molecule expression and monocyte chemoattractant 1 production but not leukocyte adhesion

NO impairs endothelial cell intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1/CCL2) induction by inflammatory stimuli. To test whether these markers are affected by IFNα, HUVECs were cultured in IFNα and showed increased expression of CCL2 and VCAM-1 expression were significantly increased compared to buffer controls (p<0.0001 and p=0.0124, respectively). ICAM-1 mRNA trended toward an increase; although, differences were not significant (p=0.068). Moreover, we observed that supernatant MCP-1 protein levels increased in response to IFNα, which confirms a functional role for IFNα in immune cell chemotaxis and adhesion to the endothelial cell surface (Figure 5A). To understand the role of NO in modulating adhesion molecule expression, we treated cells with GSNO, an amino acid NO donor, in the presence or absence of IFNα. Our studies showed that addition of NO lead to impaired upregulation of VCAM1, however, these changes were not significant (Figure 5B). As a functional assay, we assessed the impact of IFNα on this NO-modulated process in vitro. HUVECs treated with IFNα for 6h displayed significantly enhanced neutrophil surface adhesion (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5. Quantitative PCR and Neutrophil Adhesion analysis following IFN-α stimulation of HUVECs.

(A) IFNα enhances chemotactic mediators and adhesion molecule expression in HUVECs. Cells were treated with IFNα 1000 IU/ml and MCP-1 protein, CCL2, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 gene levels were examined using qRT-PCR. All values were normalized to GAPDH (n=3-4). (B) Addition of GSNO, an NO donor, partially reverses the IFNα effect on adhesion molecule expression in HUVECs. HUVECs were treated with IFNα in the presence or absences of GSNO at 25 and 250uM concentrations for 24 hours. VCAM and ICAM gene expression was examined using qRT-PCR. (C) Neutrophil adhesion to HUVECs increases after cells are stimulated with IFNα. Cells were incubated for 3 hours with IFNα 1000 IU/ml and freshly isolated neutrophils stained with calcein AM were added to cells. Fluorescence intensity was established using a fluorescent plate reader. Representative images are shown (original magnification X20). Fold change in fluorescence was quantified as shown in the bar graphs. Statistical analysis was conducted using a Student’s T-test. Data are mean fold change± SD. * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01 compared to control.

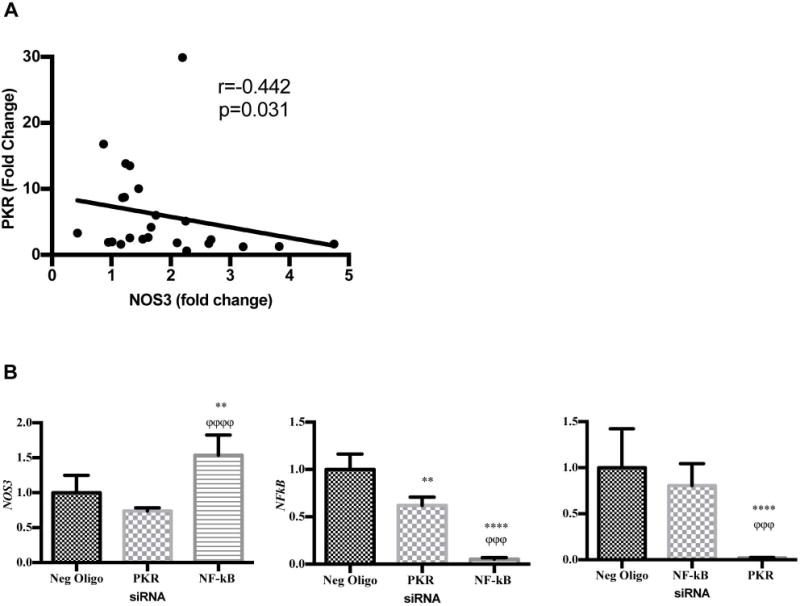

To establish the potential in vivo relevance of these findings in SLE, we analyzed levels of PKR and MX1 induction by SLE serum in relationship to NOS3 mRNA levels. NOS3 mRNA expression negatively correlated with PKR (r=-0.63, p=0.0009, Figure 6A). However, eNOS did not associate with MX1 induction (data not shown). In addition, PKR is known to enhance NF-κB activity. To determine if PKR and/or NFκB were involved in the regulation changes in NOS3 mRNA expression under conditions of IFNα treatment, we used siRNA to knockdown PKR or NFκB expression in HUVECs and determined changes in NOS3 mRNA using RT2PCR. IFNα treated HUVECs deficient in PKR had 30% lower levels of eNOS (Figure 6B). After a 6h IFNα treatment, eNOS increased 50% in NFκB-deficient cells over cells transfected with negative siRNA oligonucleotides (Figure 6B). This suggests that the effect of IFNα on eNOS may be partially due to activation NFκB and subsequent increases in downstream inflammatory targets.

FIGURE 6. IFNα promotes NOS3/eNOS suppression possibly through NF-kB upregulation.

(A) SLE serum induces correlative changes in NOS3 and PKR expression. HUVECs were treated with 20% serum for 24h. RNA isolates were examined for NOS3 and PKR expression. GAPDH was used as a control. (B) Knockdown of NFkB reverses IFNα mediated changes in NOS3 expression. HUVECs were transfected with a negative oligo, NFkB or PKR siRNA for 30h and subsequent IFN-α (1000 IU/ml) treatment for 6 hours. RNA isolates were subjected to qRTPCR and examined for NOS3, NFkB, or PKR. Values were normalized to GAPDH. The asterisk (*) denotes statistical comparison between the negative oligo and the specific siRNA treated groups. The phi (ϕ) is indicative of statistical comparison between two gene specific siRNA groups. Statistical analysis was conducted using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Fold change of the mean is reported ± SD, n=3-9. **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 and ϕϕϕp<0.005, and ϕϕϕϕp<0.0001.

Discussion

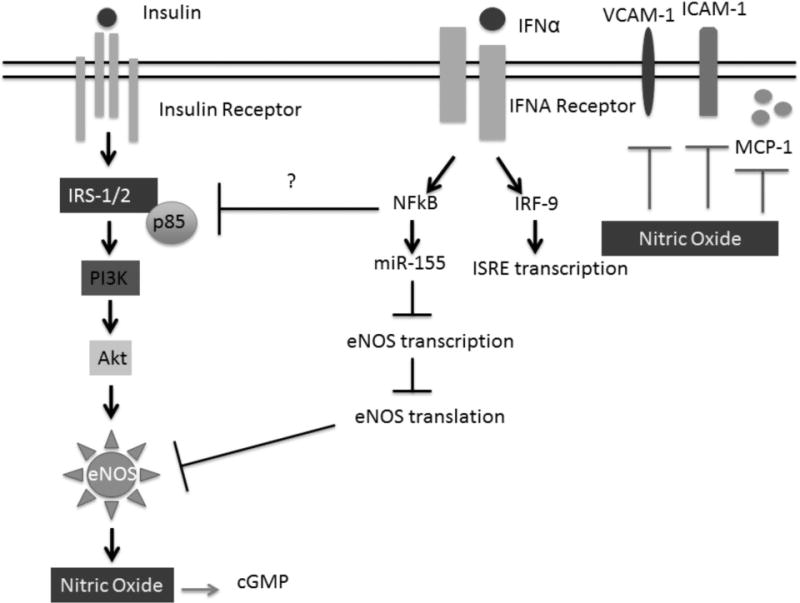

Many studies support the critical role of Type I IFNs in the pathogenesis of lupus as well as secondary clinical manifestations of the disease(12, 14, 26). Moreover, a number of studies have shown links between Type I IFN signature gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and endothelial dysfunction. Our present study shows the negative impacts of IFNα on NOS3 mRNA expression, eNOS protein expression, and insulin-mediated NO production in endothelial cells (Figure 7). Additionally, we provided evidence that suggests functional consequences and mechanisms of eNOS/NO loss in response to IFNα. For the first time, this work demonstrates that IFNα modulates eNOS, which is important for endothelial cell homeostasis and function.

FIGURE 7. IFN-α promotes insulin resistance in HUVECs.

IFN-α stimulation in HUVECs leads to enhanced NF-kB signaling and upregulation of miR-155. MiR-155 may be, in part responsible for IFN-α mediated eNOS mRNA destabilization leading to reduced protein expression. IFN-α elicits an immune response through suppression of NO and subsequent increases in MCP-1, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. It is well established that insulin activates eNOS through the PI3K/Akt pathway leading to phosphorylation of eNOS at the Serine 1177 site and subsequent increases in NO production. However, in the presence of IFN-α, enhanced NO production is lost. This suggest that IFN-α may induce insulin resistance in HUVECs.

Physiologically relevant concentrations of IFNα are difficult to discern given the lack of sensitivity and specificity of immunoassays (9) for detection in blood. Thus, interferon signature gene induction is used to understand translatable concentrations for in vitro studies. For the first time, this work shows that 1000 IU/ml IFNα and 20% SLE serum induce MX1 and PKR interferon signature genes in a similar manner. Previous studies in WISH cells have shown MX1 and IFIT1 induction levels can be quite different from the current study, depending on the concentration of serum and/or IFN (9). This may be due to differential expression of IFNAR and downstream signaling responses in endothelial vs. epithelial cells.

However, it is unlikely that IFNα in SLE serum is the only inducer of our selected IFIGs in endothelial cells. Nevertheless, previous studies suggest that it may be the dominant mediator upstream of PRKR and MX1 specific transcription. A number of cytokines and chemokines present in SLE serum may also impact expression of IFIGs, including IFNβ, IFNλ, or IFNγ, which all partially contribute to PRKR expression (27). Moreover, Cates et al., 2014 showed that IL-10 synergizes with IFNα to amplify its effects on impaired endothelial progenitor cell function(28). The presence of circulating dsDNA (CpG) immune complexes or viral agents containing dsRNA in patients may also lead to activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways that further induce IFNα signature gene induction (29).

Multiple studies have shown that IFNα is a potent pro-atherogenic factor (30); however, its impacts on early stage atherogenesis or endothelial dysfunction have only recently been investigated. In this study, we demonstrated that IFNα exerts its deleterious effects on endothelial function in part through suppression of eNOS/NOS3 mRNA expression. Furthermore, these changes negatively correlated with both IFNα and SLE serum induction of PRKR. However, only IFNα induced MX1 correlated with NOS3. This suggests that there are multiple pathways of induction in SLE serum as discussed above.

These findings are supported by a previous study that reported an association between SLE serum mediated PRKR induction in WISH cells and reduced brachial artery flow mediated dilation, a surrogate marker of endothelial dysfunction (13). Moreover, lupus endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) circulation and function are impaired in association with high type I IFIG ex vivo(31). Mobilization of EPCs is regulated by endothelial derived nitric oxide(32). Thus, one potential mechanism whereby EPC circulation is impaired in SLE patients is through type I interferon down regulation of eNOS expression as is observed in other patient populations with endothelial dysfunction. Yet, controversy exists as to whether or not NOS3 mRNA expression impacts endothelial function and nitric oxide production. For example, in hyperglycemia and diabetes, endothelial cell eNOS/NOS3 levels have been measured as increased (33), decreased (34), or unchanged (35). Moreover, when levels increase, they are typically associated with a rise in superoxide production. It is likely that eNOS mRNA expression is increased to compensate for loss of NO bioavailability or reduced activity of eNOS protein from uncoupling. Thus, eNOS expression is not likely the only regulator of functional NO production in vivo.

Systemic lupus erythematosus patients have interferon inducible gene expression in PBMCs that correlate with disease activity and endothelial dysfunction (36). This is the first study to demonstrate that that IFNα impairs insulin-mediated NO production in endothelial cells. Moreover, we show that mechanisms leading to reduced NO include loss of eNOS mRNA, protein, and possibly alterations in eNOS phosphorylation. Novel mechanisms leading to increased eNOS instability by IFN alpha may be NF-kB/miR155 mediated. These studies provide the foundation for work determining the effect of targeting IFNα-mediated pathways of ED in patients with SLE or other diseases of chronic IFNα induction as a strategy for reducing atherosclerosis.

To further understand the in vivo relevance of our findings, we compared changes in SLE serum-mediated induction of PKR expression to changes in NOS3 mRNA and showed a strong negative association between the two genes, suggesting a possible intrinsic co-regulation by IFNα. However, our experiments in which PKR induction was blocked by siRNA indicated that eNOS expression was not regulated by PKR. This suggests that the effect is not at the level of eNOS expression. PKR phosphorylates IKK independent of dsRNA-mediated activation, leading to phosphorylation of IκB-α and subsequent activation of NF-κB. Conversely, the NF-kB p50 subunit promotes eNOS transcription by binding to the shear stress response element (SSRE) in the eNOS promoter region. Surprisingly, we found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of PRKR led to further reductions in eNOS mRNA levels and NFκB, suggesting a possible protective role for PKR.

Further, we observed that NFκB knockdown resulted in a 1.5 fold increase in eNOS mRNA compared to IFNα stimulated controls. NF-κB was previously shown to upregulate eNOS transcription during shear stress by binding to the SSRE promoter region. Conversely, NF-κB activation enhances IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα production. These cytokines antagonize eNOS protein or gene expression via destabilization or changes in eNOS transcription rates. Thus, NF-KB may be regulating eNOS expression indirectly. However, the studies reported here do not address these mechanisms.

NF-κB has pleiotropic effects on eNOS expression through both transcription and post-transcriptional modification. Our studies showed that transcription was unchanged in response to IFNα. This led us to examine changes in NOS3 mRNA stability, and we observed decreases eNOS half-life with IFNα stimulation. As an anti-viral cytokine, IFNα is known to activate pathways that limit intracellular viral replication, possibly through alterations in gene stability (37).

Previous studies have reported that IFNα and NF-κB induce microRNAs (miRs) known to destabilize eNOS, including miR155 (38). MiR-155 is upregulated in atherosclerotic plaques isolated from patients with coronary artery disease (39, 40). MicroRNA-155 overexpression in HUVECs drastically reduces eNOS expression and NO production by decreasing NOS3 mRNA stability by binding to the 3’UTR region. Cytokines such as TNF-α have previously been shown to induce miR155 expression in a NF-κB dependent manner. Further, miR-155 has been shown to modulate IFNα induced anti-viral responses (41). Here, our studies demonstrated that treatment with IFNα induced miR-155 expression, which may explain the reduction observed in NOS3 mRNA expression over time. Moreover, knockdown of miR-155 in IFNα treated HUVECs resulted in enhanced NOS3 mRNA expression; however, these changes were not statistically significant. To date, studies examining upregulation of miR-155 in SLE patient atherosclerotic plaques and EPCs are missing. Our preliminary studies engender the hypothesis that miR-155 upregulation in endothelial cells by IFNα serves as one possible mechanism whereby endothelial dysfunction ensues in vivo. Future studies will need to examine factors involved downstream of PKR and NFκB, which lead to increases miR-155 expression.

We noted a decline in eNOS protein expression in response to IFNα. Surprisingly, IFNα significantly increased phosphorylation at the Thr495 site in association with diminished NO production. Nitric oxide bioavailability is modified by number of factors, including enzyme expression and activity. Thus, IFNα appears to induce activation and inactivation pathways of eNOS. Our studies are limited due to lack of direct eNOS activity measurements but strongly suggest that the ultimate effect is an inactivation of eNOS. Further, non-correlative eNOS expression and NO data may suggest a role for stimulation of inducible NOS (iNOS)-mediated NO production at 24 hours. However, we did not detect iNOS (NOS2) mRNA in our cells cultured with IFNα (data not shown).

Our findings contradict a previous study showing that IFNα2b had no impact on eNOS expression or NO production (42). Our studies differ from these in that they were conducted in HUVECs. However, preliminary findings in HAECs showed an even more drastic impact of IFNα on eNOS expression after 24hr treatment at 1000 IU/ml (data not shown). Moreover, the authors measured NO production by measuring supernatant nitrate/nitrite levels, reporting levels in the micromolar range. NO produced by eNOS is measured in the nanomolar range (43). This work may have failed to detect reductions in this surrogate of NO production because it is difficult to detect nanomolar reductions eNOS NO production when background levels are in the micromolar range.

One possible mechanism whereby IFNα may impair insulin-mediated up regulation of NO production is through PKR induction. Prior studies showed that PKR phosphorylates the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) at Ser312, an inhibitory site, and suppresses phosphorylation at that activation site, Tyr941, leading to loss of downstream signaling. Thus, upregulation of PKR may be responsible for the observed impaired insulin mediated NO production. However, we did not assess IFNα mediated changes in NO in PKR deficient cells.

NO is an anti-atherogenic molecule, with multiple downstream targets, including adhesion molecules, chemokines, and cyclic guanosine monophosphate. NO exerts it anti-atherogenic effects by inhibiting NF-κB activation in two different ways. NO promotes IκB expression preventing NF-κB activation while S-nitrosylating the cysteine group located on p50. Collectively, these mechanisms prevent nuclear localization of NF-κB and subsequent upregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and MCP-1, all of which are associated with vascular plaque formation. We showed that IFNα stimulation enhanced adhesion molecule expression and MCP-1 production in addition to neutrophil adhesion to the endothelial cell surface. MCP-1 and VCAM-1 are important for adhesion of other leukocytes such as monocytes to the endothelial cell surface. Our studies did not examine the effect of IFNα on monocyte/endothelial cell interactions. Collectively, these studies suggest that IFNα perpetuates endothelial dysfunction as evidenced by loss of NO production and upregulation of targets generally suppressed by physiologic levels of endothelium-derived NO (41).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Diane Kamen for her generosity with SLE patient samples. We would also like to thank the staff at the Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center at MUSC.

Funding Sources This research was funded by NIH Grant Number UL1 TR000062 and by the Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center at MUSC through NIH Grant Number P60 AR062755. This work was also supported by the Arthritis Foundation, NIAMS NIH grant 5R01AR045476, grant 5F31AR064150-02 (1NRSA) and NIGMS grant 5R25GM072643-10 (IMSD).

Abbreviations

- apoE (−/−)

apolipoprotein E knockout, Apoetm1Unc

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- hnRNA

heteronuclear RNA

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- IFNAR

interferon alpha/beta receptor

- ISG

interferon signature gene

- MX1

myxovirus resistance protein 1

- NO

nitric oxide

- NZB/W

New Zealand black/white

- PKR

protein kinase R

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- VED

vascular endothelial dysfunction

References

- 1.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. American journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145:408–415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Shakra M, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD. Mortality studies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Results from a single center. II. Predictor variables for mortality. The Journal of …. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urowitz MB, Bookman AAM, Koehler BE, Gordon DA, Smythe HA, Ogryzlo MA. The bimodal mortality pattern of systemic lupus erythematosus. The American Journal of Medicine. 1976;60:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Gadban MM, German J, Truman JP, Soodavar F, Riemer EC, Twal WO, Smith KJ, Heller D, Hofbauer AF, Oates JC, Hammad SM. Lack of nitric oxide synthases increases lipoprotein immune complex deposition in the aorta and elevates plasma sphingolipid levels in lupus. Cell Immunol. 2012;276:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilkeson GS, Mashmoushi AK, Ruiz P, Caza TN, Perl A, Oates JC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase reduces crescentic and necrotic glomerular lesions, reactive oxygen production, and MCP1 production in murine lupus nephritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez-Guzman M, Jimenez R, Romero M, Sanchez M, Zarzuelo MJ, Gomez-Morales M, O’Valle F, Lopez-Farre AJ, Algieri F, Galvez J, Perez-Vizcaino F, Sabio JM, Duarte J. Chronic hydroxychloroquine improves endothelial dysfunction and protects kidney in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension. 2014;64:330–337. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan MJ, McLemore GR., Jr Hypertension and impaired vascular function in a female mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2007;292:R736–742. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00168.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. The interplay of inflammation and cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011 doi: 10.1186/ar3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua J, Kirou K, Lee C, Crow MK. Functional assay of type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus plasma and association with anti-RNA binding protein autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1906–1916. doi: 10.1002/art.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer K. Risk factors of thickened intima-media and atherosclerotic plaque development in carotid arteries in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Annales Academiae Medicae Stetinensis. 2008;54:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, Somers EC, Dodick T, Barrat FJ, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Interferon-alpha promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007;110:2907–2915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thacker SG, Zhao W, Smith CK, Luo W, Wang H, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Rabquer BJ, Koch AE, Pennathur S, Davidson A, Eitzman DT, Kaplan MJ. Type I interferons modulate vascular function, repair, thrombosis, and plaque progression in murine models of lupus and atherosclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2975–2985. doi: 10.1002/art.34504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somers EC, Zhao W, Lewis EE, Wang L, Wing JJ, Sundaram B, Kazerooni EA, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Type I interferons are associated with subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of systemic lupus erythematosus patients. PloS one. 2012;7:e37000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee PY, Li Y, Richards HB, Chan FS, Zhuang H, Narain S, Butfiloski EJ, Sobel ES, Reeves WH, Segal MS. Type I interferon as a novel risk factor for endothelial progenitor cell depletion and endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3759–3769. doi: 10.1002/art.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thacker SG, Berthier CC, Mattinzoli D, Rastaldi MP, Kretzler M, Kaplan MJ. The detrimental effects of IFN-alpha on vasculogenesis in lupus are mediated by repression of IL-1 pathways: potential role in atherogenesis and renal vascular rarefaction. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:4457–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thacker SG, Zhao W, Smith CK, Luo W, Wang H, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Rabquer BJ, Koch AE, Pennathur S, Davidson A, Eitzman DT, Kaplan MJ. Type I interferons modulate vascular function, repair, thrombosis, and plaque progression in murine models of lupus and atherosclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2975–2985. doi: 10.1002/art.34504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamen DL, Barron M, Parker TM, Shaftman SR, Bruner GR, Aberle T, James JA, Scofield RH, Harley JB, Gilkeson GS. Autoantibody prevalence and lupus characteristics in a unique African American population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1237–1247. doi: 10.1002/art.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doria A, Vesco P, Zulian F, Gambari PF. The 1982 ARA/ACR criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus in pediatric and adult patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:689–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong SC, Lo ES, Cheung MT. An optimised protocol for the extraction of non-viral mRNA from human plasma frozen for three years. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:766–768. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.007880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey KA, Xu Z, Pavlina TM, Zaloga GP, Siddiqui RA. Modulation of endothelial cell integrity and inflammatory activation by commercial lipid emulsions. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:9. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser WJ, Kaufman JL, Offermann MK. IFN-alpha sensitizes human umbilical vein endothelial cells to apoptosis induced by double-stranded RNA. J Immunol. 2004;172:1699–1710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Jin J, Song M, Dong H, Zhao G, Huang L. C-reactive protein down-regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and promotes apoptosis in endothelial progenitor cells through receptor for advanced glycation end-products. Gene. 2012;496:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi L, Fleming I. One miR level of control: microRNA-155 directly regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA and protein levels. Hypertension. 2012;60:1381–1382. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.203497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng G, Nystrom FH, Ravichandran LV, Cong LN, Kirby M, Mostowski H, Quon MJ. Roles for insulin receptor, PI3-kinase, and Akt in insulin-signaling pathways related to production of nitric oxide in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;101:1539–1545. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugimoto M, Nakayama M, Goto TM, Amano M, Komori K, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase phosphorylates eNOS at threonine 495 in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan MJ. Premature vascular damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: an imbalance of damage and repair? Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2009;154:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crow MK. Interferon-alpha: a therapeutic target in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:173–186. x. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cates AM, Holden VI, Myers EM, Smith CK, Kaplan MJ, Kahlenberg JM. Interleukin 10 hampers endothelial cell differentiation and enhances the effects of interferon alpha on lupus endothelial cell progenitors. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:1114–1123. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallin H, Perers A, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies and immunostimulatory plasmid DNA in combination mimic the endogenous IFN-alpha inducer in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1999;163:6306–6313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. Mechanisms of premature atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:249–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060911-090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, Somers EC, Dodick T, Barrat FJ, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Interferon-alpha promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007;110:2907–2915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thum T, Fraccarollo D, Schultheiss M, Froese S, Galuppo P, Widder JD, Tsikas D, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling impairs endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and function in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:666–674. doi: 10.2337/db06-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauersachs J, Schafer A. Tetrahydrobiopterin and eNOS dimer/monomer ratio–a clue to eNOS uncoupling in diabetes? Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:768–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarado-Vasquez N, Zapata E, Alcazar-Leyva S, Masso F, Montano LF. Reduced NO synthesis and eNOS mRNA expression in endothelial cells from newborns with a strong family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2007;23:559–566. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Triggle CR, Ding H. A review of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: a focus on the contribution of a dysfunctional eNOS. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, Shark KB, Grande WJ, Hughes KM, Kapur V, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ota K, Matsumiya T, Sakuraba H, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Kawaguchi S, Fukuda S, Satoh K. Interferon-alpha2b induces p21cip1/waf1 degradation and cell proliferation in HeLa cells. Cell cycle. 2010;9:131–139. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.1.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun HX, Zeng DY, Li RT, Pang RP, Yang H, Hu YL, Zhang Q, Jiang Y, Huang LY, Tang YB, Yan GJ, Zhou JG. Essential role of microRNA-155 in regulating endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by targeting endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension. 2012;60:1407–1414. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartmann P, Schober A, Weber C. MicroRNA-155 and macrophages: a fatty liaison. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:5–6. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R, Dong LD, Meng XB, Shi Q, Sun WY. Unique MicroRNA signatures associated with early coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang P, Hou J, Lin L, Wang C, Liu X, Li D, Ma F, Wang Z, Cao X. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J Immunol. 2010;185:6226–6233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds JA, Ray DW, Zeef LA, O’Neill T, Bruce IN, Alexander MY. The effect of type 1 IFN on human aortic endothelial cell function in vitro: relevance to systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2014;34:404–412. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie QW, Cho HJ, Calaycay J, Mumford RA, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Ding A, Troso T, Nathan C. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science. 1992;256:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1373522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]