Abstract

Social frailty is a rather unexplored concept. In this paper, the concept of social frailty among older people is explored utilizing a scoping review. In the first stage, 42 studies related to social frailty of older people were compiled from scientific databases and analyzed. In the second stage, the findings of this literature were structured using the social needs concept of Social Production Function theory. As a result, it was concluded that social frailty can be defined as a continuum of being at risk of losing, or having lost, resources that are important for fulfilling one or more basic social needs during the life span. Moreover, the results of this scoping review indicate that not only the (threat of) absence of social resources to fulfill basic social needs should be a component of the concept of social frailty, but also the (threat of) absence of social behaviors and social activities, as well as (threat of) the absence of self-management abilities. This conception of social frailty provides opportunities for future research, and guidelines for practice and policy.

Keywords: Social frailty, Social vulnerability, Scoping review, Social needs

Introduction

Frailty is a widely used concept that describes a complex state of increased vulnerability due to adverse health outcomes related to ageing. However, there is an ongoing debate on the nature of the concept of frailty with, on the one hand, models and concepts stressing the physical aspects of frailty (Fried et al. 2004) and, on the other hand, integral models that emphasize the multidimensional aspects (De Vries et al. 2011; Rockwood 2005). These latter models emphasize the biopsychosocial dynamic nature of the frailty concept and describe the pathway from life-course determinants and disease(s) to frailty and then to adverse outcomes (Gobbens et al. 2010a). The underlying idea is that frailty increases with the accumulation of physical, psychological, and social deficits (or problems). Physical, psychological, and social frailty have been described in the realm of the overall frailty concept (van Campen 2011). Of these three domains, social frailty is the most unexplored concept. Considering that older adults must increasingly rely on their (informal) social relationships and social environment—due to policy measures aimed at reducing the financing of formal care and support—the concept of social frailty becomes ever more important and thus requires clear conceptualization. A better understanding of what it comprises and how it evolves is important for identifying this infirmity, but also for preventing it and for designing policy measures to address it.

Some studies have explicitly defined social frailty as insufficient participation in social networks (or no participation at all) and the perception of a lack of contacts and support (e.g., Broese van Groenou 2011). However, most of the literature is still inconclusive on the nature and scope of social frailty as a concept and demonstrates significant variety in the approaches to the concept. Others have explored the influence of social deficits or problems on frailty as social vulnerability and discovered a moderate, but distinct, relationship of social vulnerability with overall frailty (Andrew et al. 2008a).

In order to generate a comprehensive understanding of what comprises social frailty, a broad and systematic evaluation of existing insights is needed. To synthesize these insights, we started with the basic proposition that, on a higher abstraction level, social frailty could be considered as a lack of resources to fulfill one’s basic social needs. Fulfillment of basic social needs is necessary to function adequately and experience social wellbeing, just as basic physical needs fulfillment is required to experience physical wellbeing. Different social needs theories exist, among others Self Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci 2000), loneliness theories (Dykstra and Fokkema 2007), and the theory of Social Production Functions (SPF) (Lindenberg 2013; Ormel et al. 1999; Steverink and Lindenberg 2006). In contrast to most theories, which often consider only one or two generic social needs (e.g., the need for emotional and/or social connectedness), SPF theory specifies three distinctive social needs, which allow a more nuanced analysis of the important social resources and activities that are needed to fulfill these needs. The three needs according to SPF theory are the needs for affection, behavioral confirmation, and status. Affection is the fulfillment of the need to love and to be loved regardless of one’s assets or actions. Behavioral confirmation is the fulfillment of the need to feel that one is doing the “right” thing according to relevant others and oneself, and to be part of a group with shared values. Status is the fulfillment of the need to distinguish oneself from others by means of specific talents or assets. When resources are insufficient, the fulfillment of these three basic social needs becomes threatened and will cause people to become socially vulnerable or frail. SPF theory states that the more a person is able to fulfill each of the three social needs by having the appropriate resources, the more overall social wellbeing will be experienced. Conversely, the lower the levels of need fulfillment of the three needs, the more socially vulnerable or frail a person will be and, consequently, the more this person will be at risk of decreased levels of social wellbeing.

This paper aims, therefore, to evaluate existing insights on social frailty, and structure and synthesize these insights in a scoping review (Pham et al. 2014), using the social needs concept of SPF theory as heuristic for ordering and structuring these insights. By doing so, we aim to arrive at an integrated conceptualization of social frailty that outlines opportunities for future research and provides guidelines for practice and policy.

Methods

Search strategy

A search was performed using the PubMed, Embase, Psychinfo and Socindex databases encompassing all years up to October 2016. The following search string was used:

(“Social frailty”[Title/Abstract] OR frailty [Title/Abstract] OR frailties [Title/Abstract] OR “Social vulnerability”[Title/Abstract] OR “Social vulnerabilities”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “Aged, 80 and over”[MeSH Terms] OR “Frail Elderly”[MeSH Terms] OR “frail elderly”[Title/Abstract]) AND (English [Language] OR Dutch [Language] OR German [Language])

Selection process

In the first step of selection, two independent reviewers reviewed all of the titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant articles. Studies were included if they described the concept of social frailty, contained a definition or determinants of social frailty, or social determinants of overall frailty, or if they contained a combination of all of these criteria. Studies written in English, Dutch, or German were included, and duplicates were excluded. After completion, all studies that were selected by either one or both of the two reviewers were included for the next step.

In the second step of selection, the included papers from step 1 were retrieved in full text and again reviewed by the same independent reviewers using the same criteria as used in step 1. The reference lists of these papers were examined for any that were missed in the search process during the first step. After completion, the two independent reviewers discussed the papers and agreed on inclusion. If no consensus was reached, a third independent reviewer made the final decision.

Data extraction

The two reviewers extracted all factors from the papers that could be identified as being related to social frailty. To enhance a broad scope of factors related to social frailty, no selection was made based on the nature of the mentioned factors in the papers. For example, they could be part of an existing (frailty) index (such as, for example, social loneliness or social isolation) or be part of studies related to frailty (for example socioeconomic status or age).

Synthesis of the data

In order to structure the factors retrieved from the literature, the social needs concept of SPF theory was utilized, which could provide a way to order and synthesize the factors found. The intention was to arrive at an overall framework and possibly integrate all factors that were ascertained to be related to social frailty. Based on the framework of SPF theory, it was assessed whether the factors that we found in the literature could be interpreted and categorized in terms of: (1) the result of general social need fulfillment (N); (2) social resources which are likely to be used for fulfillment of one or more of the social needs (S); (3) non-specific or general resources, i.e., not specifically stipulated for a specific social need but rather beneficial in a more general and indirect way for fulfilling social needs , for example, educational level or income (G); and (4) social behaviors or social activities that are likely to be exploited for social need fulfillment (B).

Results

Search results

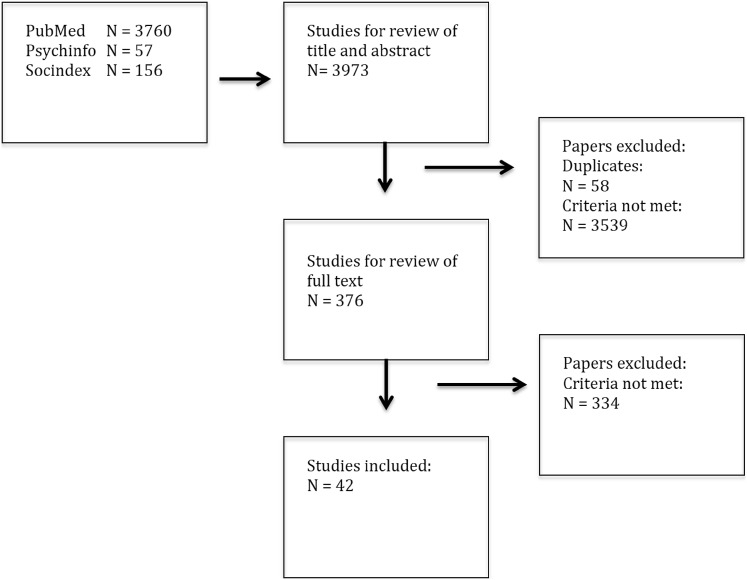

In the first step, the search revealed 3973 hits of which most were found in Pubmed (3760). After a selection based on titles, abstracts, and exclusion of duplicates, 376 papers were retrieved in full text for examination. Finally, in the second step, 42 papers were included for this scoping review. A flowchart of the selection process is presented in Fig. 1. Examination of the available reference lists of these 42 studies did not reveal additional studies.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection process

Results data extraction and synthesis

All studies that were selected, and all of the factors related to social frailty selected by the two reviewers, are presented in Table 1. The table also describes to which of the components of SPF theory [social Needs fulfillment (N), Social resources (S), General resources (G), and social Behaviors or activities (B)] the factors in the different studies belong. Of all of the included studies, 26 studies mentioned factors that were identified as basic social need fulfillment (N), 29 mentioned factors that were identified as social resources (S), and 36 studies mentioned factors identified as general resources (G), while six studies mentioned factors identified as social behaviors and/or activities (B). Most of the incorporated studies have a cross-sectional design (24), while there were only a few studies having a longitudinal design (5). Papers that described the same instrument (for example, an index) were collapsed in one row in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected studies (alphabetically), study types, factors derived from the studies and which components of SPF theory the studies address: social Needs fulfillment (N), Social resources (S), General resources (G) and social Behaviors or activities (B)

| References | Type of study | Factors related to social frailty | N | S | G | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarado et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional study | Adulthood socioeconomic situation (educational level, occupation) Childhood socioeconomic situation (health, family’s economic situation, hunger) Perceived sufficiency of income, marital status |

X | X | ||

| Ament et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional study | Educational level Financial situation Living-alone status |

X | X | X | |

| Andrew et al. (2008b), Andrew and Rockwood (2010), Armstrong et al. (2015), Shega et al. (2012) and Wallace et al. (2015) | Construction of a questionnaire based on survey | Ability to read or write Leisure activities Marital status Feel empowered Feel in control of life situation Maintaining close relationships Experience of warm and trusting relationships Does income currently satisfy needs Home ownership Education Social support Socially oriented activities of daily living |

X | X | X | X |

| Aranda et al. (2011) | Longitudinal cohort study | Age Cognitive performance Education Emotional support Financial strain Gender Neighborhood composition: ethnic homogeneity Nativity Positive affect Type of insurance |

X | X | ||

| Bilotta et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional study | Age Civil status Gender Home ownership status Home surface area Living alone Main characteristics of the caregivers if present, both informal (i.e., unpaid) and/or formal (i.e., paid) Yearly family income Years of schooling |

X | X | ||

| Casale-Martinez et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional study | Ability to make important decisions Amenities in the home Educational level Employment benefits Elderly abuse Financial support Friends or family living in the same neighborhood Home ownership History of childhood illness Living offspring Marital status Occupational history Parents’ educational level Religiosity Socioeconomic status Volunteering |

X | X | X | |

| Cramm and Nieboer (2013) | Cross-sectional study | Age Educational level Marital status Sex Social cohesion and a sense of belonging within the neighborhood |

X | X | X | |

| Etman et al. (2012) | Longitudinal cohort study | Age Level of education Marital status Sex |

X | X | ||

| Garre-Olmo et al. (2013) | Observational, prospective and population-based study | A person to help with ADL Contact with family/friends/neighbors Help from others with daily living Frequency of contact with family Frequency of contact with friends/neighbors Living alone Presence of a confidant |

X | |||

| Gobbens et al. (2010a, b, c, d, 2012a, b, c, 2013, 2015) | 2010 Literature study 2010a Literature study 2010b Cross-sectional study (index) 2010c Literature study and qualitative design (expert panel) 2012 Cross-sectional study (index) 2012a Cross-sectional study (index) 2012b Longitudinal study 2013 Cross-sectional study 2015 Cross-sectional study |

Age Education Ethnicity Income Influence of life events Living alone Living environments Marital status Sex Social support Social relationships |

X | X | X | |

| Harttgen et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional study | Education Income |

X | |||

| Herrera-Badilla et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional study | Loneliness | X | |||

| Heppenstall et al. (2009) | Literature review | Education Low income Social isolation Socioeconomic status in childhood |

X | X | ||

| Hoogendijk et al. (2016) | Longitudinal population-based study | Emotional support Instrumental support Loneliness Social network size |

X | X | ||

| Hsu and Chang (2015) | Longitudinal study | Age Education Financial satisfaction Sex Social engagement |

X | X | ||

| Imuta et al. (2001) | Cross-sectional study (survey) & interview | Functional ability Involvement in neighbors Social support |

X | X | X | |

| Jurschik et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional study (survey) | Age Educational level Gender Income Family ties Living situation (alone, w/o) Lifestyle Marital status Social participation Social ties |

X | X | X | |

| Kawano-Soto et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional study | Age Care from family member Education Financial support Family/friends in the same neighborhood Friends/family to assist in case needed Sex |

X | X | ||

| Lang et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional study | Individual SES (wealth) Neighborhood deprivation |

X | X | ||

| Makizako et al. (2015) | Prospective cohort study | Feeling helpful to friends or family Going out less frequently compared with last year Living alone Talking with someone every day Visiting friends sometimes |

X | X | X | |

| Mulasso et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional study | Loneliness Social isolation |

X | |||

| Peek et al. (2012) | Longitudinal cohort study | Age Education Gender Marital status Size of household Social support: perceived emotional support Financial strain, health life events, non-health life events |

X | X | ||

| Sánchez-García et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional study | Age Education Gender Marital status Limitations in the basic activities or daily living Living situation No paid work |

X | X | X | |

| Santos-Eggimann et al.(2009) | Cross-sectional study | Country (north/south)-differences in frailty (not explained by demographics, except education | ||||

| St John et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional study | Age Gender Social position: education, income security, income satisfaction, home ownership Emotional and provided support Health problems living situation |

X | X | ||

| Szanton et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional study | Education Household income |

X | |||

| Theou et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional study | GPD per capita Healthcare expenditure |

||||

| De Witte et al. (2013) | Development and validation study of frailty index | Social loneliness Social support |

X | |||

| Woo et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional study | Education Income Job Lifestyle factors: physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, vegetable and fruit intake, fish intake Social support: amount siblings, amount children (in law), amount grandchildren, amount relatives, contact w/relatives Total expenses |

X | X | X | |

| Woo et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional study | Gender Lifestyle Socioeconomic status Social support network |

X | X |

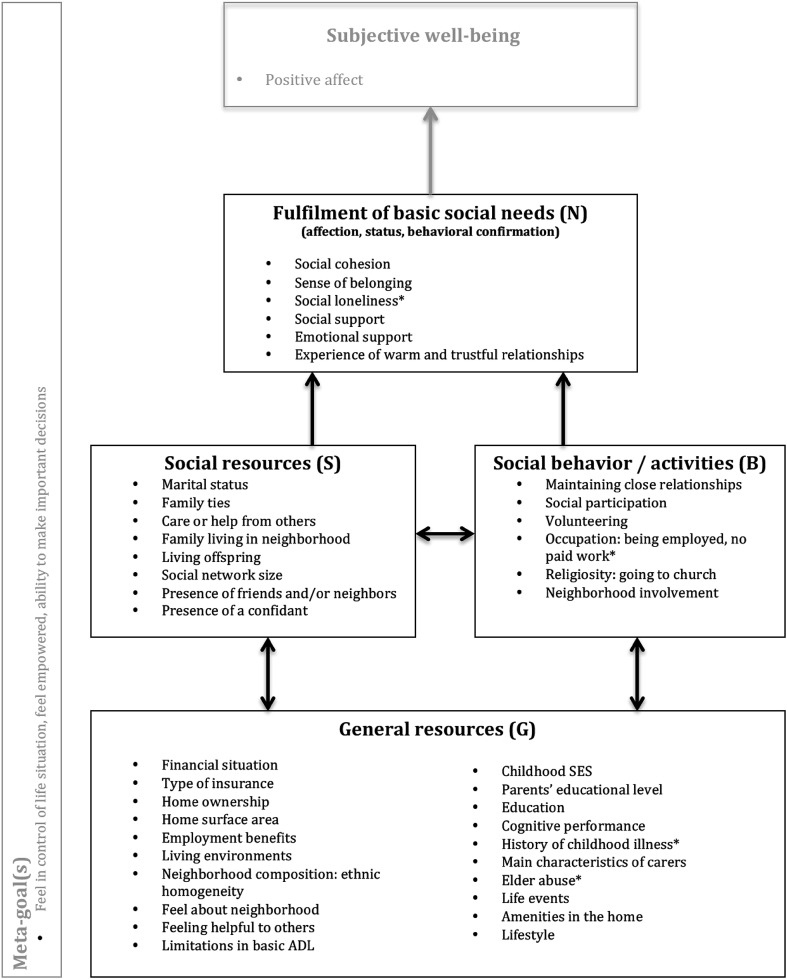

Nearly all factors found in the studies could be categorized according to components of SPF theory. Two studies containing 2 factors (GDP per capita, and frailty differences between countries) could not be categorized, but contained variables related to social frailty. Closely related factors were collapsed into more general categories. For example, the ability to read or write, educational level, education, and years of schooling were collapsed into the general category education (see Fig. 2). Three factors (found in various studies, see Table 1) could not be identified as social needs fulfillment, social resources, general resources, or social behaviors or activities. These were: feel in control of life situation, feel empowered, and the ability to make important decisions. However, these factors can be interpreted as abilities or skills that are functional in social need fulfillment. The theory of Self-Management of Wellbeing (SMW theory), which is an extension of the SPF theory, specifies these behaviors as self-management abilities (Steverink 2014; Steverink et al. 2005). Finally, the factor “positive affect” can be interpreted as a higher-level outcome of social need fulfillment, i.e., as one component of subjective wellbeing (Diener et al. 1999). Figure 2 depicts the synthesis of all factors into a conceptual model of social frailty with the various types of resources (or restrictions), social behaviors and activities, general resources, and self-management abilities, all in the function of adding to (or affecting) social needs fulfillment.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model of social frailty with the various types of social and general resources (or restrictions), social behaviors and activities, and self-management abilities all in the function of adding to (or affecting) social needs fulfillment. Asterisks negatively formulated

The synthesis shows that out of all incorporated studies (42), a considerable number contained factors relating to social frailty could be interpreted as social need fulfillment (17) and social resources (19). Nearly all studies mentioned factors that could be interpreted as general resources in relationship to social frailty. Factors relating to social behaviors and activities, as well as self-management abilities, were mentioned rarely. Additionally, only five papers, all from the same research group, addressed factors that relate to all components of social frailty according to the conceptualization in this paper (Andrew and Mitnitski 2008; Andrew and Rockwood 2010; Andrew et al. 2012; Armstrong et al. 2015; Wallace et al. 2015).

Discussion

In our synthesis, nearly all factors found could be structured according to the social needs concept as specified by SPF theory (Lindenberg 2013; Ormel et al. 1999; Steverink and Lindenberg 2006). Following this synthesis, social frailty can be understood as a multidimensional concept with a variety of general and/or social resources (or restrictions), social behaviors and activities, and self-management abilities, which all have a function in adding to (or affecting) social needs fulfillment. Social frailty, in this aspect, can be defined as a continuum of being at risk of losing, or having lost, social and general resources, activities, or abilities that are important for fulfilling one or more basic social needs during the life span. The results of this scoping review indicate that not only the (threat of) absence of social and/or general resources (e.g., a spouse or children) should be a component of the concept of social frailty but also the (threat of) absence of activities or social behaviors such as maintaining cohesive relationships or social participation as well as self-management abilities such as feeling empowered or having the ability to make important decisions.

Our synthesis revealed that most studies addressed factors that relate to social need fulfillment, social resources and general resources in relation to social frailty. This suggests that, in the current literature, social frailty is primarily seen as a matter of having (or not having) general and social resources, indicating that social behaviors and activities, as well as self-management abilities, are underestimated components in the conception of social frailty thus far. This could imply that, on the one hand, these aspects might not be equal components of the domain of social frailty. Various components of social frailty might differ in importance. On the other hand, these aspects might be neglected components in field of social frailty up until now. A possible explanation for this unawareness could be that, in most of the literature found, social frailty has not been understood in terms of a social needs perspective. However, a social needs perspective seems useful for arriving at a meaningful conceptualization of social frailty.

This synthesis has utilized the social needs concept of SPF theory to structure and integrate the data. However, the social needs concept of SPF theory is more specific than has been applied in this synthesis, because SPF theory distinguishes three basic social needs: the needs for affection, behavioral confirmation, and status. For this synthesis, it was not possible to attribute the different factors specifically to one or more of the three social needs, because most factors found in the literature were formulated in a rather generic way and, therefore, could not be assigned to a specific social need. For example, social participation can add to the fulfillment of all three social needs depending on how it is defined: an individual can receive affection when interacting with close friends, receive behavioral confirmation when participating in a group of volunteers, or receive status when participating in the board of a political party. In order to obtain a more detailed analysis of which factors contribute to the specific social needs, a specification of the factors related to social frailty would be necessary.

In the analysis, a number of factors could not be directly placed in our conceptual model. Gender was ascertained to be a variable related to social frailty in various studies (Table 1). However, it is difficult to identify it as a resource, activity, or ability. Nevertheless, gender could be a variable that relates to social frailty. Although the literature is still inconclusive, a number of authors report on gender-specific social orientations. For example, men appear to be more status-oriented, and women more affection-oriented (Cross and Madson 1997). There also may be gender differences in possibilities for substitution and compensation between different social need fulfillment (Steverink et al. 1998). It also appears that women are frail more often than men (Gobbens et al. 2010b; Woo et al. 2005), and women more frequently than men remain alone after their partner has passed away (Broese van Groenou 2011). Thus, social frailty may be more prevalent in women, and women may be more at risk of becoming socially frail. Age was also found to be related to social frailty in various studies, but seems to be more of a correlate of general and social resources, that are important for social need fulfillment, than being a resource itself. For example, an individual might lose his or her spouse when becoming older, or not be able to participate in social groups to the same extent as before. However, age per se need not be the limiting variable. Therefore, in this perspective, age itself seems to be a risk factor of becoming socially frail, rather than being a component of social frailty as such. The variables ethnicity, nativity, GDP per capita, and frailty differences between countries, all relate to cultural differences in social frailty among people. Between countries and cultures, differences may exist in the presence of different resources (for example, differences in family ties or friends), the type of behaviors/activities people perform (for example, differences in social participation), and the way in which they realize their social need fulfillment. Yet, although the cultural context may vary, the understanding of social frailty as presented in this paper and its underlying mechanisms remains the same; although general and social resources as well as social behaviors or activities may vary between countries and cultures, they are still likely to contribute to social needs fulfillment.

In this paper, a scoping review was performed, instead of a systematic review, because we aimed to gain a broad theoretical scope on the concept of social frailty, and to include all factors possibly related to the concept. By not primarily focusing on issues of quality appraisal, this scoping study potentially yielded a greater range of study designs and methodologies than a systematic review would have done. A scoping review, in contrast to a systematic review, offers the possibility to apply a qualitative approach in synthesizing the knowledge on the topic of social frailty, and therefore best suited the aim of this paper. In this synthesis, we were able to integrate our findings along a theoretical heuristic, which strengthens our conclusions.

Notwithstanding the advantages of a scoping review, also a disadvantage needs to be mentioned. All factors that might be relevant for a better understanding of the concept of social frailty were selected without considering their relative weight or abstraction level. For example, the factors that were found could be items of a scale that was used in some study, or they might be aspects of social frailty that were mentioned in a literature review. Therefore, the relative importance of the different factors in our conceptual model was not considered, but could be relevant for the concept of social frailty. Future studies should, therefore, address this issue in order to gain a deeper understanding of the relative importance of specific factors in relation to social frailty.

This scoping review provides several directions for further research. Although the social needs of SPF theory have been tested empirically in a wide range of studies, the specific conception of social frailty, and the specific aspects of it, as presented in this paper should be further examined in order to test its validity and scientific potential. First, the relative importance of general resources, social resources and social activities, and/or behaviors for understanding social frailty among older people needs to be explored. Are both equally important to prevent social frailty, and how do these resources and activities interact? This knowledge could contribute to a better understanding of the dynamics between these factors and the importance of the components in the emergence of social frailty. Second, the factors discovered by our synthesis need to be specified and analyzed in more detail in order to determine which of the three basic social needs they fulfill. This might contribute to a more in-depth understanding of the conception of social frailty as presented in this paper, since fulfillment of all three needs is important for the experience of overall wellbeing (Steverink and Lindenberg 2006). Third, the self-management abilities that people use to gain or maintain social and other resources also need to be specified in more detail. There is already a substantial literature on the concept of self-management of wellbeing, and specific self-management abilities have been proposed in relationship to social need fulfillment (Goedendorp and Steverink 2016; Steverink and Lindenberg 2008). This would contribute to a better understanding of the role of self-management abilities in the conception of social frailty.

For practice and policy, the conception of social frailty as presented in this paper can be of use for understanding the dynamics of social frailty among older people. Using the model presented in this paper, it becomes possible to identify which resources, activities and/or behaviors, and abilities that have the potential to fulfill basic social needs, are lacking in this population. Additionally, it becomes possible to design interventions that aim at preventing or delaying social frailty. Concretely, individual or group interventions targeted at socially frail older people should address resources, activities, and/or behaviors and abilities that have the potential to fulfill social needs, as well as the abilities to manage these resources. Moreover, given that social behaviors and activities, as well as self-management abilities, seem to be underexposed components of social frailty, these aspects deserve specific attention in care and welfare practices.

Considering that older adults must increasingly rely on their (informal) social relationships and social environment—due to policy measures aimed at reductions in the financing of formal care and support—it is important that interventions aimed at prevention or delay of social frailty target all relevant aspects for every individual. Based on the results of this study, it seems that interventions that are only aiming at generic solutions (for example, improving the living environment) do not fully address the individual dynamics of social frailty, i.e., in terms of individual social resources, activities and abilities. This potentially leads to suboptimal outcomes and poor cost-effectiveness of these interventions. Our results indicate that policy and interventions should be aimed at both the social resources of individual older people (for example, care from family members) as well as their personal activities and/or social behaviors (for example, their social participation), next to their self-management ability regarding their social resources and activities (for example, the ability to make and maintain friends or to initiate social participation). The synthesis presented in this paper provides a theory-based starting point for designing such interventions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Responsible editor: H. Litwin

References

- Alvarado BE, Zunzunegui MV, Beland F, Bamvita JM. Life course social and health conditions linked to frailty in Latin American older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1399–1406. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.12.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ament BH, de Vugt ME, Koomen FM, Jansen MW, Verhey FR, Kempen GI. Resources as a protective factor for negative outcomes of frailty in elderly people. Gerontology. 2012;58:391–397. doi: 10.1159/000336041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew MK, Mitnitski AB. Different ways to think about frailty? Am J Med. 2008;121:e21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew MK, Rockwood K. Social vulnerability predicts cognitive decline in a prospective cohort of older Canadians. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(319–325):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew MK, Mitnitski AB, Rockwood K. Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew MK, Mitnitski AB, Rockwood K. Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew MK, Mitnitski A, Kirkland SA, Rockwood K. The impact of social vulnerability on the survival of the fittest older adults. Age Ageing. 2012;41:161–165. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, Ray LA, Snih SA, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS. The protective effect of neighborhood composition on increasing frailty among older Mexican Americans: a barrio advantage? J Aging Health. 2011;23:1189–1217. doi: 10.1177/0898264311421961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JJ, Andrew MK, Mitnitski A, Launer LJ, White LR, Rockwood K. Social vulnerability and survival across levels of frailty in the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Age Ageing. 2015;44:709–712. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilotta C, Case A, Nicolini P, Mauri S, Castelli M, Vergani C. Social vulnerability, mental health and correlates of frailty in older outpatients living alone in the community in Italy. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:1024–1036. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.508772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broese van Groenou M. Sociale kwetsbaarheid. In: Cv Campen., editor. Kwetsbare ouderen. Den Haag: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau; 2011. p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Casale-Martinez RI, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Avila-Funes JA. Social determinants of frailty in elderly Mexican community-dwelling adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:800–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Relationships between frailty, neighborhood security, social cohesion and sense of belonging among community-dwelling older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:759–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: self-construals and gender. Psychol Bull. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries N, Staal J, Van Ravensberg C, Hobbelen J, Rikkert MO, Nijhuis-Van der Sanden M. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Witte N, Gobbens R, De Donder L, Dury S, Buffel T, Schols J, Verte D. The comprehensive frailty assessment instrument: development, validity and reliability. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Fokkema T. Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: Comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;29:1–12. doi: 10.1080/01973530701330843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etman A, Burdorf A, Van der Cammen TJ, Mackenbach JP, Van Lenthe FJ. Socio-demographic determinants of worsening in frailty among community-dwelling older people in 11 European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:1116–1121. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garre-Olmo J, Calvo-Perxas L, Lopez-Pousa S, de Gracia Blanco M, Vilalta-Franch J. Prevalence of frailty phenotypes and risk of mortality in a community-dwelling elderly cohort. Age Ageing. 2013;42:46–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. In search of an integral conceptual definition of frailty: opinions of experts. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Towards an integral conceptual model of frailty. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:175–181. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Determinants of frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Schols JM. Testing an integral conceptual model of frailty. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:2047–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Schols JM. The predictive validity of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator: disability, health care utilization, and quality of life in a population at risk. Gerontologist. 2012;52:619–631. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Young frail elderly: assessed using the Tilburg Frailty Indicator. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;43:296–307. doi: 10.1007/s12439-012-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, van Assen MA. Explaining quality of life of older people in the Netherlands using a multidimensional assessment of frailty. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2051–2061. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, Krans A, van Assen MA. Validation of an integral conceptual model of frailty in older residents of assisted living facilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedendorp MM, Steverink N. Interventions based on self-management of well-being theory: pooling data to demonstrate mediation and ceiling effects, and to compare formats. Aging Ment Health. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1182967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harttgen K, Kowal P, Strulik H, Chatterji S, Vollmer S. Patterns of frailty in older adults: comparing results from higher and lower income countries using the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE) PLoS One. 2013;8:e75847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppenstall CP, Wilkinson TJ, Hanger HC, Keeling S. Frailty: dominos or deliberation? N Z Med J. 2009;122:42–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Badilla A, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Amieva H, Avila-Funes JA. Loneliness is associated with frailty in community-dwelling elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:607–609. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk EO, Suanet B, Dent E, Deeg DJ, Aartsen MJ. Adverse effects of frailty on social functioning in older adults: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Maturitas. 2016;83:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC, Chang WC. Trajectories of frailty and related factors of the older people in Taiwan. Exp Aging Res. 2015;41:104–114. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2015.978219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imuta H, Yasumura S, Abe H, Fukao A. The prevalence and psychosocial characteristics of the frail elderly in Japan: a community-based study. Aging (Milano) 2001;13:443–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurschik P, Nunin C, Botigue T, Escobar MA, Lavedan A, Viladrosa M. Prevalence of frailty and factors associated with frailty in the elderly population of Lleida, Spain: the FRALLE survey. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano-Soto CA, Garcia-Lara JM, Avila-Funes JA. A poor social network is not associated with frailty in Mexican community-dwelling elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2360–2362. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IA, Hubbard RE, Andrew MK, Llewellyn DJ, Melzer D, Rockwood K. Neighborhood deprivation, individual socioeconomic status, and frailty in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1776–1780. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg S. Social rationality, self-regulation, and well-being: the regulatory significance of needs, goals, and the self. In: Wittek R, Snijders TAB, Nee V, editors. Handbook of rational choice social research. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2013. pp. 72–112. [Google Scholar]

- Makizako H, Shimada H, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, Doi T, Nakakubo S, Hotta R, Suzuki T. Social frailty in community-dwelling older adults as a risk factor for disability. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:1003.e7–1003.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulasso A, Roppolo M, Giannotta F, Rabaglietti E. Associations of frailty and psychosocial factors with autonomy in daily activities: a cross-sectional study in Italian community-dwelling older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:37–45. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S95162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Lindenberg S, Steverink N, Verbrugge LM. Subjective well-being and social production functions. Soc Indicators Res. 1999;46:61–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1006907811502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Howrey BT, Ternent RS, Ray LA, Ottenbacher KJ. Social support, stressors, and frailty among older Mexican American adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:755–764. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. 2014;5:371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K. What would make a definition of frailty successful? Age Ageing. 2005;34:432–434. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García S, Sánchez-Arenas R, García-Peña C, Rosas-Carrasco O, Ávila-Funes JA, Ruiz-Arregui L, Juárez-Cedillo T. Frailty among community-dwelling elderly Mexican people: Prevalence and association with sociodemographic characteristics, health state and the use of health services. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:395–402. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Eggimann B, Cuenoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:675–681. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shega JW, Andrew M, Hemmerich J, Cagney KA, Ersek M, Weiner DK, Dale W. The relationship of pain and cognitive impairment with social vulnerability—an analysis of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Pain Med. 2012;13:190–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John PD, Montgomery PR, Tyas SL. Social position and frailty. Can J Aging. 2013;32:250–259. doi: 10.1017/S0714980813000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N (2014) Successful development and ageing:84

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S. Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychol Aging. 2006;21:281–290. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S. Do good self-managers have less physical and social resource deficits and more well-being in later life? Eur J Ageing. 2008;5:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Ormel J. Towards understanding successful ageing: patterned change in resources and goals. Ageing Soc. 1998;18:441–467. [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Slaets JJ. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanton SL, Seplaki CL, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Allen JK, Fried LP. Socioeconomic status is associated with frailty: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:63–67. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theou O, Brothers TD, Rockwood MR, Haardt D, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Exploring the relationship between national economic indicators and relative fitness and frailty in middle-aged and older Europeans. Age Ageing. 2013;42:614–619. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Campen C (eds) (2011) Frail older persons in the Netherlands. The Netherlands Institute for Social Research, The Hague

- Wallace LM, Theou O, Pena F, Rockwood K, Andrew MK. Social vulnerability as a predictor of mortality and disability: cross-country differences in the survey of health, aging, and retirement in Europe (SHARE) Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Goggins W, Sham A, Ho SC. Social determinants of frailty. Gerontology. 2005;51:402–408. doi: 10.1159/000088705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Chan R, Leung J, Wong M. Relative contributions of geographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors to quality of life, frailty, and mortality in elderly. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]