Abstract

Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell density-dependent regulation of virulent bacterial gene expression by autoinducers that potentially pertains in the epidemic of bacterial virulence. This study was initially designed to evaluate the effect of 5 phenolic compounds in the modulation of QS and virulence factors of Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and to determine the mechanisms of their effects. Biosensor strains were used to assess antibacterial and anti-QS effect of these compounds. Only methyl gallate (MG) among these compounds demonstrated profound anti-QS effect in the preliminary study, and thus only MG was utilized further to evaluate the effects on the synthesis and activity of acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) in C. violaceum and on the modulation of biofilm, motility, proteolytic, elastase, pyocyanin, and rhamnolipid activity in P. aeruginosa. Finally, the effect of MG on the expression of QS-regulated genes of P. aeruginosa was verified. MG suppressed both the synthesis and activity of AHL in C. violaceum. It also restricted the biofilm formation and other QS-associated virulence factor of P. aeruginosa. MG concentration-dependently suppressed the expression of lasI/R, rhlI/R, and pqsA of P. aeruginosa and was non-toxic in in vitro study. This is the first report of the anti-QS mechanism of MG.

Introduction

Quorum sensing (QS) is an inter-cellular communication system of bacteria that is used to collectively control group behaviors1, 2. This process depends on the production, release, and group-wide detection of signal molecules which are known as autoinducers. The autoinducers in gram-negative bacteria are typically homoserine lactones (HSLs)1, 2. LuxI-type enzymes involved in the production of HSLs, and LuxR-type cytoplasmic proteins act as the receptors of HSL1, 2. LuxR-type receptors can be stabilized by binding with autoinducers, and this stabilization enables the dimerization, binding of DNA, and the transcription of QS target genes3, 4. LuxI/R signaling cascades are essential for the virulence in many pathogenic bacteria, and the virulence of these bacteria can be prevented by disabling these circuits with small molecules2.

C. violaceumis an aquatic, saprophyte, gram-negative bacterium that occasionally acts as a pathogen of extreme virulence, and causes fatal septicemia, lung and liver abscesses, and skin lesions5. C. violaceum produces violacein pigment in response to QS regulated gene expression6. Considering this characteristic, this bacterium is widely used to study the inhibition of acyl homoserine lactone (AHL)-dependent QS by diverse compounds7–9. The utilization of this bacterium is also very common in the assessment of short chain AHL production, because of the tight AHLs-QS control over the production of violacein pigment10. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that causes morbidity and mortality in immune-compromised patients such as cystic fibrosis, AIDS, cancer patients and severe burn victims11. This organism depends on two key LuxI/R QS systems, namely Las and Rhl systems, for organizing simultaneous production of biofilm and virulence factors12. The autoinducer molecule, 3-oxo-C12-HSL is produced by LasI and responded by LasR in P. aeruginosa. The LasR:3-oxo-C12-HSL complex activates the transcription of many genes including rhlR, that encodes a second QS receptor13. RhlR binds to the autoinducer C4-HSL, the product of RhlI. RhlR:C4-HSL also directs a large regulon of genes, some of which are also members of the LasR regulon13. This tandem regulatory arrangement allows LasI/R to control the first stage of QS-controlled gene expression, and RhlI/R to control the second one. Because, LasR activates the expression of rhlR, and thus, the expression of both LasR- and RhlR-regulated target genes are reduced by the deletion of lasR 14, 15.

QS-dependent regulation of gene expression controls a wide variety of phenotypes including bioluminescence, biofilm formation, drug resistant, virulence factors expression, and motility. Therefore, the inhibition of QS is considered to be a new promising target of antimicrobial pathway as anti-virulence compounds, which can repress the gene expression and are essential for the basic metabolism in vitro, rather than the microorganism itself16. QS attracts attention as a promising anti-pathogenic drug target rather than antibacterial, notably preventing the emergence of drug resistant bacteria, because many pathogenic bacteria employ QS to regulate their pathogenicity and virulence factor production17, 18. Molecules that target QS have been proposed as an anti-virulence strategy. Efforts to identify small molecule inhibitors of QS were reviewed recently11, 19–24. Generally, the QS inhibitors work by the (i) inhibition of QS signal molecule biosynthesis, (ii) degradation and inactivation of QS signal molecules, and (iii) inhibition of signal molecule detection by receptors. Investigators have identified a variety of inhibitors by performing cell-based screens, or by synthesizing AHL analogs22, 25–28.

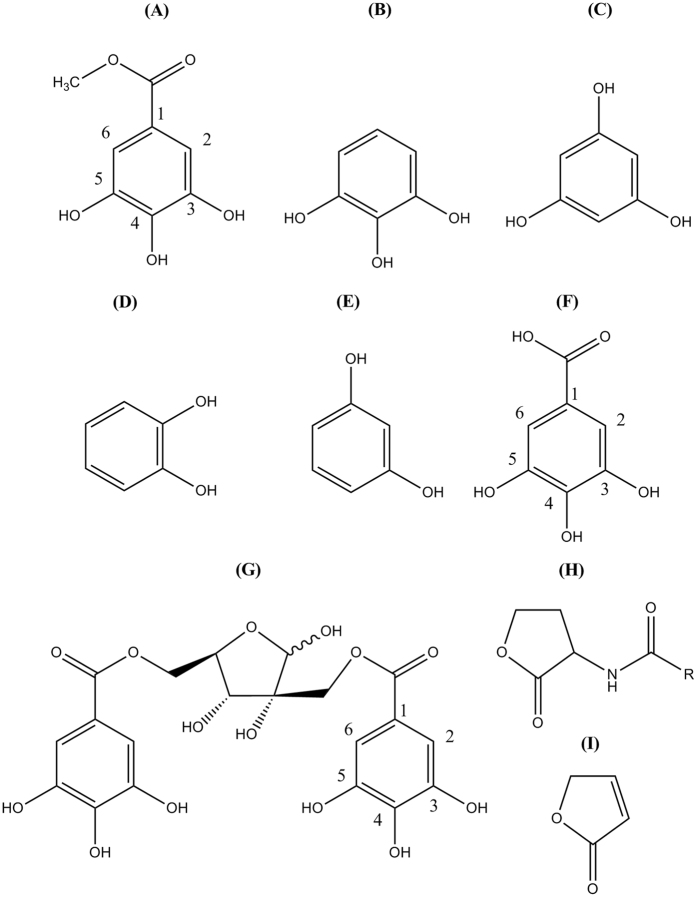

For this study, we have selected 5 phenolic compounds (MG, pyrogallol, pyrocatechol, resorcinol and phloroglucinol) (Fig. 1). These phenolic compounds commonly contain phenol ring with attached hydroxyl groups, but they differ in the number and positions of these additional hydroxyl groups. Moreover, the MG has a methyl ester group at its 1 position. On the other hand, the QS signal molecule, AHL has a lactone ring and amide group. So, these phenolic compounds are different than AHL considering their basic structures and their attached functional groups or side chain. The furanone also has lactone ring as like in AHL and is used as AHL analogue. But, this compound is different than the above mentioned phenolic compounds in view of their basic structure. The pyrogallol, a trihydroxybenzene having the same central structure like MG except of having methyl ester was reported for QS inhibition in Vibrio harveyi, where the QS is regulated by three pathways29, 30. Hamamelitannin, a polyphenolic compound with the basic galloyl moiety showed QS inhibitions against S. aureus 31.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of selected phenolic compounds and their similarity/dissimilarity with autoinducer molecule. Chemical structure of (A) methyl gallate, (B) pyrogallol, (C) phloroglucinol, (D) pyrocatechol, (E) resorcinol, (F) gallic acid, (G) hamamelitannin, (H) acyl-homoserine lactone, and (I) furanone. Structures were drawn by ChemDraw software.

Methyl Gallate is reported to have antioxidant, anticancer, antivirus, anti-inflammatory, antiasthmatic and vasodilative activities32. This compound exhibited substantial inhibitory effects on the protein synthesis and succinate dehydrogenase activity in a plant pathogen33. Treatment of Ralstonia solanacearum with MG showed that this compound can interfere with their respiration and metabolism33. The three hydroxyl groups at the phenyl ring of MG correspond to the important portion of the molecule for activity (pharmacophore)30. This information is supported by Ni et al. who evaluated pyrogallol derivatives, and showed that they confer QS antagonist activity30. The alkyl-ester of gallic acid was responsible to show its activities specifically against biofilm of S. mutans, which initiates this speculation that the methyl ester of gallic acid (MG) may also work against biofilm of P. aeruginosa (PAO1)34. Additionally, many phenols can non-specifically affect molecular targets of microorganisms. They contain a large number of hydroxyls, therefore can form protonic and ionic bonds and combine with many proteins of some bio-organisms like enzymes, carriers, ion channels and receptors, deactivating them and consequently exhibit bacterial inhibition35.

The existence of large proportion of MG and pyrogallol in ethyl acetate fraction of Nymphaea tetragona 50% methanol extract (NTME) has been determined by chromatographic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1) in our earlier study together with the synergistic antibacterial and anti-QS effect of NTME36. Previously, we also evaluated the potentials of MG-containing NTME in the inhibition of QS as well as virulence factors in C. violaceum (ATCC12472) and P. aeruginosa (PAO1)37. At the initial stage of the current study, it was intended to develop precise QSIs by evaluating the QS inhibition potentials of 5 phenolic compounds (MG, pyrogallol, pyrocatechol, resorcinol and phloroglucinol), targeting mainly to the opportunistic compound MG. We also aimed to study the influence of the most potent QSI among these 5 phenolic compounds on P. aeruginosa QS-regulated virulence factors production, motility and biofilm formation. Furthermore, the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying to the suspected effects of the most potent QS inhibitors were aimed to evaluate.

Results

MIC and MBC of phenolic compounds

The MIC and MBC values of structurally related 5 phenolic compounds against three strains of C. violaceum (ATCC12472, ATCC31532 and CV026), and P. aeruginosa (PAO1) are presented in Table 1. The MICs of MG, phloroglucinol, pyrocatechol, pyrogallol, and resorcinol were 32–512 μg/mL, 2048 μg/mL, 64–512 μg/mL, 4–64 μg/mL and 2048 μg/mL, respectively. The MBC values of all these compounds were 2- to 4-times higher than MIC values against these strains.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bacteriocidal concentration (MBC) of phenolic compounds against three strains (ATCC12472, ATCC31532, and CV026) of Chromobacterium violaceum, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1).

| Name of Drug | Concentrations | Chromobacterium violaceum | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC12472 | ATCC31532 | CV026 | PAO1 | ||

| Methyl Gallate (μg/mL) | MIC | 128 | 32 | 64 | 512 |

| MBC | 256 | 64 | 128 | 2048 | |

| Phloroglucinol (μg/mL) | MIC | 2048 | 2048 | 2048 | 2048 |

| MBC | 8192 | 4096 | 4096 | 8192 | |

| Pyrocatechol (μg/mL) | MIC | 64 | 128 | 64 | 256 |

| MBC | 128 | 256 | 128 | 512 | |

| Pyrogallol (μg/mL) | MIC | 8 | 4 | 4 | 64 |

| MBC | 16 | 8 | 8 | 256 | |

| Resorcinol (μg/mL) | MIC | 2048 | 1024 | 2048 | 2048 |

| MBC | 4096 | 2048 | 4096 | 4096 | |

| Norfloxacin (μg/mL) | MIC | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.25 |

| MBC | 0.0625 | 0.032 | 0.0625 | 1 | |

Quorum sensing inhibition of phenolic compounds

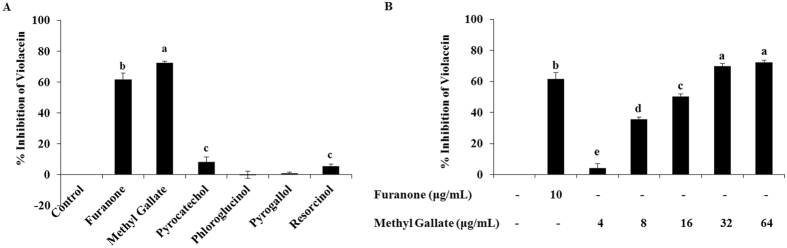

The inhibition diameters of violacein pigment of C. violaceum in presence of phenolic compounds are presented in Table 2. MG significantly inhibited the production of violacein pigment, even with the lowest concentration (15 μg/disk) used in this assay (Supplementary Fig. 2). Pyrogallol in all tested concentrations showed bactericidal effect (clear zone). Pyrocatechol showed a small diameter of pigment inhibition zone with 60 μg/disk. Other compounds with the tested concentrations were not found to be effective enough to interfere in the production of violacein by C. violaceum. Furanone confirmed the violacein pigment inhibition, whereas the negative control and tetracycline displayed no effect and bactericidal effect, respectively. In quantitative determination, MG, pyrocatechol and resorcinol were found to inhibit the production of violacein about 72.24, 8.39 and 5.49% respectively, compared to the drug-free control (Fig. 2A). Phloroglucinol and pyrogallol could not inhibit violacein production significantly. The supplementation of MG in C. violaceum culture showed concentration dependent effect on violacein inhibition (Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Quorum sensing inhibition activity (as pigment inhibition zone diameters) of phenolic compounds against Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC12472.

| Drug | Concentrations | Pigment Inhibition Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| (µg/disk) | Mean ± SD | |

| Tetracycline | 10 | 20.33 ± 1.53* |

| Furanone | 10 | 14.00 ± 1.00c |

| Normal Saline | — | — |

| Methyl gallate | 15 | 12.67 ± 1.15c |

| 30 | 16.67 ± 1.15b | |

| 60 | 23.33 ± 2.08a | |

| Phloroglucinol | 15 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 30 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 60 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Pyrocatechol | 15 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 30 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 60 | 9.33 ± 0.58d | |

| Pyrogallol | 15 | 10.33 ± 0.58* |

| 30 | 11.00 ± 1.00* | |

| 60 | 13.33 ± 0.58* | |

| Resorcinol | 15 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 30 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 60 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

Different superscript alphabets indicate significant difference (P > 0.05) in violacein pigment inhibition diameter. *Diameter of clear zone. Data shown represent the mean ± SD of three replicates.

Figure 2.

Quantitative quorum sensing inhibition ensuing percent (%) violacein inhibition of (A) 5 phenolic compounds (methyl gallate, phloroglucinol, pyrocatechol, pyrogallol, and resorcinol), and (B) Concentration-dependent percent (%) violacein inhibition of methyl gallate. Data represent the mean ± SD of triple determinations. Different superscript characters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Effects of MG on AHL synthesis and AHL activity

The effects of MG on the synthesis of AHL and on the activity of AHL were determined passively from the intensity/concentration of violacein pigment, which is the general measure of quorum sensing that can be happened if AHLs bind to their cognate receptors6. Two strains of C. violaceum (ATCC31532 and CV026) were used in this study. C. violaceum ATCC31532 is a C6-HSL over-producer strain, which can only synthesis the signal molecule but, cannot respond to that signal molecule38, 39. Conversely, C. violaceum biosensor strain (CV026) is a mini-Tn5 mutant of C. violaceum ATCC31532, which does not produce signal molecule such as C6-HSL, but has CviR receptor and shows response to the exogenous C6-HSL38, 39. In this assay, the presence of violate violacein color represents the availability of AHL and the binding of the AHL molecules to the AHL receptor, whereas the absence of violate color indicates the lack of AHL and/or AHL-receptor binding40.

It was found in the qualitative agar diffusion assay that MG at sub-lethal concentrations reduced AHL production from the AHL over-producer strain (Supplementary Fig. 3A) as indicated by the absence or indistinct pigmentation of violacein (Supplementary Fig. 4) produced by the biosensor strain (CV026). MG also appeared to interfere with the activity of AHL in the CV026/31532 bioassay system which was assessed by the production of low levels of AHL-mediated violacein pigment in CV026 AHL biosensor (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Our results indicated that compared to the control which did not contain any drug, the AHL-mediated violacein pigment production in CV026 and its activity were much lower in the presence of MG (Supplementary Fig. 3).

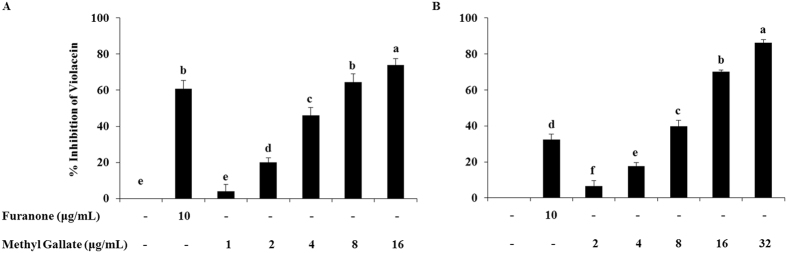

Together with the qualitative determination, we quantified the extent of MG to both in the inhibition of AHL synthesis by the AHL over producer strain ATCC31532, and in the interference with the AHL activity in biosensor strain (CV026) by utilizing two independent assays with the CV026/31532 bioassay in broth media. AHLs were extracted from C. violaceum ATCC31532 after treating them with different sub-MIC concentrations of MG and incubated the biosensor strain CV026 in presence of those extracted AHLs without any drug compounds to determine the effects of MG on the synthesis of AHL. The synthesis of AHL were inhibited about 20%, 46%, 64%, and 74% in contrast to the drug-free control, by the supplementation of 2, 4, 8 and 16 μg/mL of MG, respectively (Fig. 3A). In determining the effects of MG on the activity of AHL, we incubated the AHL over producer strain C. violaceum ATCC31532 without any treatment and extracted the AHL. The biosensor strain CV026 were incubated with those extracted AHL and treated at the same time with different sub-MIC of MG. The activity of AHL was restricted about 7%, 18%, 40%, 70%, and 86% compared to the drug-free control, in presence of 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 μg/mL of MG, correspondingly (Fig. 3B). The extents of synthesized AHL and their activity were determined by the OD values of violacein. The result indicated that the MG more effectively inhibited the activity of AHL, compared to the inhibition of AHL synthesis.

Figure 3.

A quantitative determination of the effect of methyl gallate on AHL synthesis and their activity. Effects on (A) AHL synthesis, and (B) AHL activity. Data represent the mean ± SD of triple experiments. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

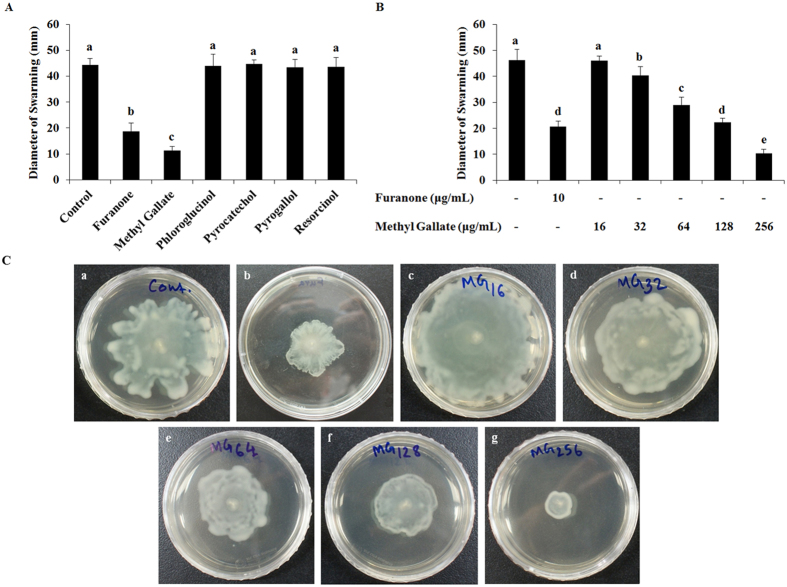

Effects of phenolic compounds on swarming motility

The effect of these phenolic compounds in the inhibition of swarming motility of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) was examined, and the results showed that only MG among these 5 compounds significantly restricted the swarming motility in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4A). Moreover, MG inhibited the swarming motility of P. aeruginosa in a dose-dependent manner at sub-MIC (Fig. 4B,C). The diameter of swarm zones were about 46, 40, 29, 22, and 10 mm, respectively in presence of 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG, whereas the swarm zone diameter in non-treated sample was about 46 mm (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Swarming motility of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) in presence of five phenolic compounds. Swarming zone diameters of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) in presence of (A) 1/2 × MIC of methyl gallate, phloroglucinol, pyrocatechol, pyrogallol and resorcinol, (B) 16~256 µg/mL of methyl gallate. (C) Representative swarm plates incubated with the supplementation of increasing concentrations (16~256 µg/mL) of methyl gallate. Data represent the mean ± SD of triple determinations. Different superscript letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

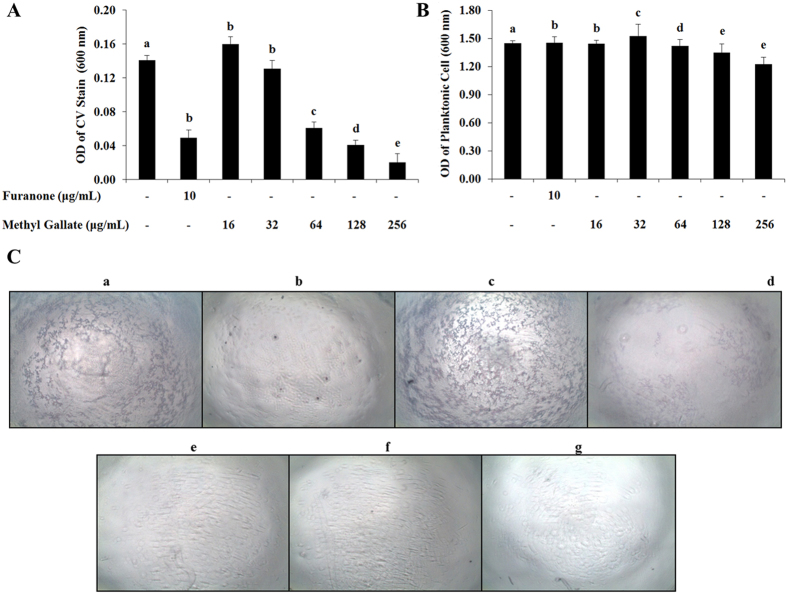

Effects of MG on biofilm formation and its viability

The impact of MG on biofilm formation was determined by keeping the bacterial culture in static condition with/without MG to develop biofilms. The result showed that the biofilm formation was inhibited concentration-dependently with the addition of sub-MIC of MG (Fig. 5A). The optical density (OD) values of crystal violet stain that retained on biofilms were about 0.160, 0.131, 0.060, 0.041 and 0.020 with the treatment of 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG, respectively. The photographs of crystal violet stained-biofilms on the surface of wells also showed that the MG concentration-dependently inhibited the formation of biofilm (Fig. 5C). The effect of MG on planktonic cell growth was also determined (Fig. 5B). There was no significant variation in OD values of planktonic cell suspension indicates that the compound has no impact on planktonic cell growth.

Figure 5.

Effects of methyl gallate in the inhibition of biofilm formation. The OD values of (A) crystal violet solution extracted from the biofilm cell surface, and (B) planktonic cell suspension at a wavelength of 600 nm. (C) Representative photographs of crystal violet stained biofilm cells on 96-well surface under light microscope where, (a) control; (b) furanone 10 µg/mL; (c–g) 16~256 µg/mL of methyl gallate. Violet spots on surface indicate biofilm. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate assays. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

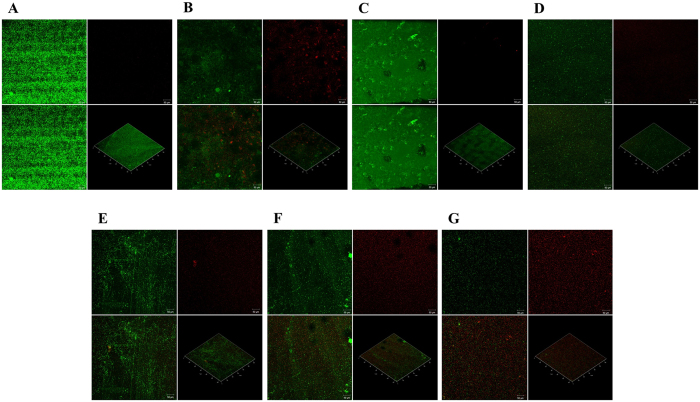

The viability of biofilm in presence of MG was determined by staining the biofilm with BacLight live/dead stain and by scanning in confocal microscope. The confocal micrograph of 48 h biofilm of P. aeruginosa treated with MG for 24 h displayed a lower proportion of live cells (cells that stained green) than that observed in the untreated control (Fig. 6). It is clearly visible that almost all cells were alive in the control biofilm. About 0.00%, 4.00%, 12.00%, 45.00%, and 70.00% dead cells (cells that stained red) were evident from the treatment with 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG, respectively.

Figure 6.

Viability of biofilm in presence of 16~256 µg/mL of methyl gallate. The confocal microscopic images of LIVE/DEAD stained biofilm in (A) drug free control; biofilm treated with (B) furanone 10 µg/mL; (C) 16 µg/mL, (D) 32 µg/mL, (E) 64 µg/mL, (F) 128 µg/mL, and (G) 256 µg/mL of methyl gallate. The viability of the biofilms was assessed using BacLight LIVE/DEAD stain (green: live cells, red: dead cells). In each image, the segment at below right side shows three dimensional and other three segments shows two dimensional images.

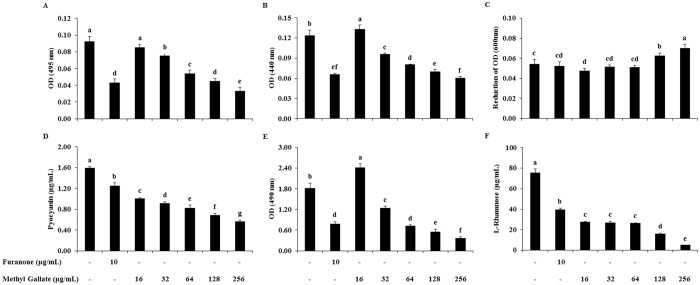

Effects of MG on the Inhibition of virulence factor production

The potentials of MG in down-regulating QS-associated virulence factors of P. aeruginosa were measured and are shown in Fig. 7. The activity of elastase, total protease, pyocyanin, exopolysaccharide, and rhamnose in P. aeruginosa (PAO1) were inhibited by MG with a dose-dependent manner. The supplementation of MG (16~256 μg/mL) in P. aeruginosa (PAO1) culture inhibited the activity of elastase (8~64)%, total protease (−7~51)%, pyocyanin (37~64)%, exopolysaccharide (−33~79)%, and rhamnose (63~93)%, compared to the activity found in drug-free control. The sub-MICs of MG above than 1/32 × MIC (16 μg/mL), concentration-dependently restricted the activities of these 5 virulent factors, and 1/32 × MIC of MG in P. aeruginosa increased the activity of total protease and exopolysaccharide compared to the non-treated control. On the other hand, LasA Staphylolytic activity was not inhibited in sub-MICs of MG (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effects of methyl gallate on virulence factors production. (A) Elastolytic activity, (B) Total proteolytic activity, (C) LasA Staphylolytic activity, (D) Pyocyanin production, (E) Exopolysaccharide production, (F) L-rhamnose production in presence of increasing concentrations (16~256 µg/mL) of methyl gallate. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate analyses. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

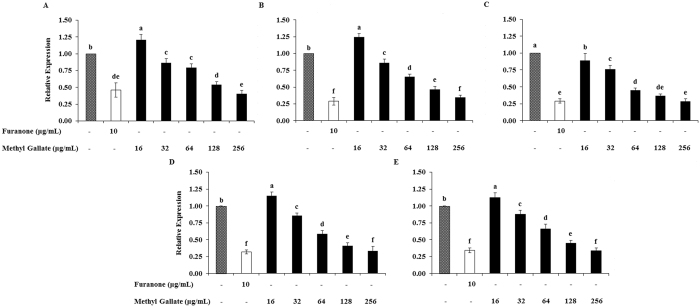

Effects of MG on QS gene expression

In P. aeruginosa (PAO1), four regulatory genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR) are very crucial to control the expression of many factors such as the virulence, pathogenicity, and biofilm development. The expressions of many other regulatory genes involve in QS are also controlled by these four particular genes41. Another important regulatory gene pqsA which is regulated by the las system and also regulates the rhl system42, 43. In addition to these regulatory genes, other QS regulator genes have been identified. But, their roles in QS are not fully understood yet44, 45. Thus, we evaluated the expressions of these 5 genes in this study. The expressions of QS-regulatory genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR and pqsA) of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) were down regulated concentration-dependently and significantly when incubated this bacterium in presence of MG. Real time PCR revealed that 59.85 ± 0.60, 65.41 ± 0.65, 71.58 ± 0.72, 66.68 ± 0.67, and 66.00 ± 0.66% expressions of lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR and pqsA, respectively reduced with the treatment of 1/2 × MIC (256 μg/mL) of MG compared to the expressions recorded in drug-free control (Fig. 8). Two fold reduced expressions of all these genes except for lasI were found in 1/4 × MIC (128 μg/mL) of MG-supplemented culture compared to drug-free control. The optimization of incubation time for better expression of lasR genes in P. aeruginosa (PAO1), and the optimization of the amount of 3-oxo-C12-HSL need to supplement for better expression of QS genes are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Figure 8.

Relative expressions of quorum sensing regulated genes of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) in presence of increasing concentrations (16~256 µg/mL) of methyl gallate. (A) lasI, (B) lasR, (C) rhlI, (D) rhlR, and (E) pqsA. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate analyses. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

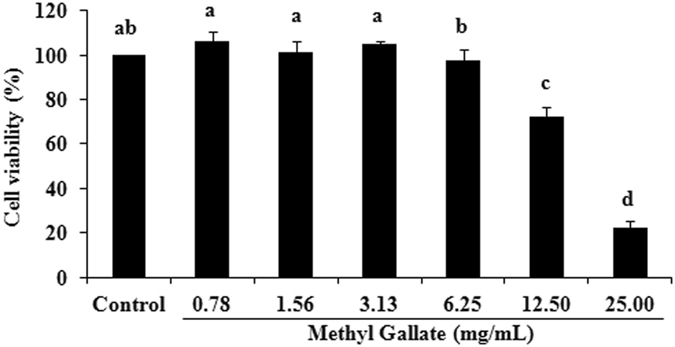

Effects of MG on cell viability

The effect of MG on the viability of RAW 264.7 cell line was evaluated to determine the safety profile of this compound. The effects of different concentrations (0.78–25.00 mg/mL) of MG on RAW 264.7 cell line are presented in Fig. 9. The MG < 6.25 mg/mL did not produce significant toxic effect. Methyl gallate concentration-dependently suppressed the viability of RAW 264.7 cells, when exposed in 6.25–25.00 mg/mL for 24 h. The reductions of viable cells in presence of 6.25, 12.50 and 25.00 mg/mL of MG were 2.34%, 27.78%, and 77.66% of the non-treated control cells, respectively. The IC50 value of MG in RAW 264.7 cells was 16.94 mg/mL.

Figure 9.

Effect of methyl gallate on the viability of Raw 264.7 cell. Data represent the mean ± SD of triple assays. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Discussion

Antimicrobials, whether bactericidal or growth inhibitory, place strong selective pressures on bacteria to develop resistance, and their widespread use has accelerated the emergence of resistant pathogens. Though there is a desperate need for the discovery and production of novel antimicrobials, an investment in developing new strategies that target mechanisms of virulence rather than bacterial growth may offer therapeutic potential that is more sustainable. These so-called anti-infective therapies would ideally target bacterial pathways that lead to disease but not interfere with bacterial growth. Thus, this study explored the interference of 5 phenolic compounds with AHL-mediated QS and demonstrated that MG among these compounds suppresses the regulation of QS through the inhibition of both AHL synthesis and the activity of synthesized AHL in C. violaceum. This compound was also found to repress the expression of genes encoding the virulence factors elastase, protease, exopolysaccharide and rhamnose, and prevents swarming motility and biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa (PAO1). We have employed comprehensive biochemical, molecular and genetic techniques to support our conclusions.

All the phenolic compounds evaluated in this study exhibited different degrees of bacterial inhibition against C. violaceum and P. aeruginosa (Table 1). A general overview of the MIC results showed that the tested phenolic compounds were comparatively less effective than a classical antimicrobial (e.g. norfloxacin) against these Gram-negative bacteria. Pyrogallol was found to be the most effective antibacterial agent, followed by pyrocatechol, MG, resorcinol, and phloroglucinol. The MBC values of these drugs are 2–4 folds higher than the MIC values against these bacteria which indicate the rational antibacterial therapeutic windows of these drugs.

The QS inhibition potentials of these phenolic compounds against C. violaceum were determined by disk agar diffusion and broth incubation assays, which demonstrate the promising anti-QS activity of MG. In the disk diffusion assay, the clear zone without any bacterial cells around the disk represents antibacterial activity, which is caused by tetracycline in this study (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furanone 10 μg/disk, different concentrations (15, 30 and 60 μg/disk) of MG, and 60 μg/disk of pyrocatechol showed QS inhibition as they only inhibited the violet violacein pigment around the disk without affecting the bacterial cell (Table 2). The QS inhibition effect of MG presented in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2 is comparable with the previously reported anti-QS activity of caffeine and mycofabricated biosilver nanoparticles46–48. In the quantitative study, violacein pigment production of C. violaceum was also inhibited significantly and concentration-dependently by MG (Fig. 2) whereas the other phenolic compounds did not noticeably inhibit the violacein pigment production. Interestingly, the sub-MIC of MG repressed the violet violacein production of C. violaceum without restricting the growth of bacterial cells. Natural and synthetic molecules were also reported to inhibit violacein production concentration-dependently without inhibiting bacterial growth49–51, which justifies the potentials of MG as QSI (Fig. 2).

The results of the qualitative and quantitative assays in the present study (Fig. 3, and Supplementary Fig. 3) have demonstrated that MG not only interferes with AHL activity, but also affects the synthesis of AHL. Effects of MG on the synthesis of AHL were determined by the OD value of violacein produced by the biosensor strain C. violaceum CV026 in presence of the AHLs that were extracted from the MG-treated cultures of C. violaceum ATCC31532. Conversely, the OD value of violacein produced in C. violaceum CV026 culture treated with sub-MICs of MG with added AHL from untreated cultures of C. violaceum ATCC31532 were measured to determine the effect of MG on the activity of AHL. The effect of MG on the activity of AHL is independent of the effects on AHL synthesis (as explained in result section). Hence, the results of this assay indicate that MG can inhibit QS either by accelerating the degradation or inactivation of AHL molecule, or reducing the ability of bacteria to synthesize AHL molecules or by inhibiting the AHL-receptor binding52–54. The suppression of AHL synthesis can happen by decreasing the expression of the LaxI/LasI family of synthases. While these mechanisms are most likely, it is also possible that MG may act as ligand or may directly restrict the virulence factor production in bacteria in a QS-independent manner.

It is observed in different studies that the compounds which inhibit QS in the Chromobacterium system also inhibit the production and/or secretion of QS-related virulence factors in Pseudomonas 55. The results of this study also suggest that MG among these phenolic compounds inhibited QS, as well as decreased the production of QS-regulated virulence factors in P. aeruginosa. In addition to flagella and pili, swarming of P. aeruginosa also requires the production of two bio-surfactants; rhamnolipids and 3-hydroxyalkonics acids56. It is reported in different studies that the production of rhamnolipids in P. aeruginosa (PAO1) is controlled by QS57. Our results (Fig. 4) indicate that only MG among these compounds showed observable inhibition against the swarming of P. aeruginosa with the formation of bacterial colony of short and undefined tendrils. Furthermore, the dose-dependent inhibition of swarming motility in the presence of MG suggests that the compound might has some effects on flagella-related processes, namely, flagella biosynthesis, rotation, and chemotaxis, which may lead to decrease in swarming activity.

P. aeruginosa has been shown to form organized, surface-attached microbial communities, called biofilms. This trait has been linked to pathogenicity of the organism in relation to pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Several studies have previously demonstrated that swarming motility is required for biofilm dispersion and it is assumed from the results of swarming inhibition of MG that this compound might inhibit the dispersion of biofilm58. The staining of biofilm cells with crystal violate proved a concentration-dependent inhibition effect of MG on the formation and growth of biofilm (Fig. 5). This finding demonstrated that the compound in sub-MIC can inhibit the development of biofilm without affecting the planktonic cell growth. The surviving and dead biofilm populations were verified by live/dead staining, where the bacterial biofilms stained green are considered as live biofilm cell and those stained red are recognized as dead cells. The results clearly showed that MG can affect the viability of biofilm of P. aeruginosa in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6). Biofilms are encased in a matrix composed of exopolysaccharide59.

There are three exopolysaccharides (alginate, Pel and Psl) produced by P. aeruginosa, and all of these exopolysaccharides have been found to contribute in biofilm formation60. Exopolysaccharide production in P. aeruginosa was significantly reduced with the treatment of MG (Fig. 7E). Earlier reports indicate the importance of pyocyanin in P. aeruginosa virulence61. Pyocyanin is a blue colored pigment produced by P. aeruginosa, which found in the sputum of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis, and has a great role in pulmonary tissue damage62. MG significantly reduced pyocyanin pigment production in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7D). P. aeruginosa strains that overproduce pyocyanin are also known to produce other extracellular virulence factors, such as proteases, which are believed to play a major role in pathogenesis, especially during acute infections63. We determined that the incubation of P. aeruginosa in presence of MG also affects the production of two proteases, the LasB elastase and the LasA staphylolytic protease (Fig. 7A–C). P. aeruginosa elastase is a strong exotoxin that induces tissue damage; therefore, significant efforts are giving to develop chemical compounds that suppress elastase activity. LasA protease has a vital function in the pathogenesis of bacteria by means of host tissue degradation37.

Rhamnolipids have been detected in sputum from cystic fibrosis patients and are known to lyse polymorpho nuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and monocyte-derived macrophages, resulting in necrotic cell death64. They have role in the maintenance of mushroom-shaped macrocolonies and in the opening of channels in mature biofilm. Rhamnolipids also play a role in overcoming surface tension and allow swarming motility of P. aeruginosa 65. MG reduced rhamnolipid production significantly and concentration-dependently (Fig. 7F). Pyocyanin, elastase, protease and rhamnolipids are regarded as indicators of the optimal operation of QS regulon in P. aeruginosa. Reduction in their production level indicates the anti QS potential of MG. Both swarming and pyocyanin are produced and regulated by the rhl system in P. aeruginosa. Therefore, collectively inhibition of P. aeruginosa swarming motility and pyocyanin production suggests the presence of rhl inhibitor61. Total protease and elastase are directly controlled by the las system, and pyocyanin and rhamnolipid are mainly regulated by the rhl system66. The reduction in virulence factors controlled by 3-oxo-C12-HSL (elastase and protease) and C4HSL (rhamnolipids and pyocyanin) in P. aeruginosa (PAO1) indicates the reduction in both AHLs67.

The expression of lasR was comparatively better when they incubated for 16 h in presence of 100 μM of 3-oxo-C12-HSL (autoinducer). The incubation time was optimized for having the maximum expressions of QS-regulated genes, as the incubation times reported in different articles are different68, 69. The amount of autoinducer (3-oxo-C12-HSL) required to supplement was also optimized for the induction of lasI/R and rhlI/R cascade in P. aeruginosa (PAO1). Real-time polymerase chain reaction showed that MG concentration-dependently down regulated the transcriptions of autoinducer synthase (lasI and rhlI) and their cognate receptor (lasR and rhlR) genes, which resulted in attenuation of QS-regulated virulence activities, such as biofilm formation, and secretion of pyocyanin, elastase, protease, exopolysaccharides and rhamnolipid. The protease and elastase are las-controlled virulence factors, pyocyanin and rhamnolipid is controlled by rhl system70, 71. The reduction rates of elastolytic activity (64%), proteolytic activity (51%), pyocyanin (64%), exopolysaccharide (79%), and rhamnose (93%) for 1/2 × MIC of MG showed that this compound has stronger effect both on lasR and rhlR. Further, the las system contributes greatly to biofilm formation, and substantial down-regulated transcription of lasR and lasI may be directly responsible for the reduction of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) biofilms72, 73. More potent antagonists do not exhibit superior function in impeding virulence. Since, lasR and rhlR reciprocally control crucial virulence factors. Appropriately tuning rather than completely inhibiting their activities appear to hold the key to blocking pathogenesis. These results suggest that MG may possess lasR inhibitory activity against the virulence of P. aeruginosa (PAO1).

The evaluation of safety/toxicity profiles of any drug is desirable and essential with the investigation of pharmacological effects. Moreover, P. aeruginosa is especially dangerous in cystic fibrosis, and it is reported recently that the dysfunction of macrophage cell is considered to be the first step in cascade of events leading to chronic inflammation/infection in cystic fibrosis74. Alternatively, maintaining the macrophage cells in safe condition is essential to remain active the body’s own defensive system. Moreover, RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line is extensively used as a reliable cell model for inflammation research and for the study of macrophage cellular physiology because of their ease of culture, rapid growth rate and phenotypic resemblance to primary macrophages75, 76. Hence, the cytotoxic effect of MG was evaluated in RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line to determine whether this compound has any interference in the defensive mechanism or not. The in vitro cytotoxicity of the compound was evaluated using the MTT assay in the current study. The MG exhibited non-toxic effect against RAW 264.7 cells. The compound in 0.78–6.25 mg/mL did not interfere the viability of cells, and high concentrations (12.50 and 25.00 mg/mL) of this compound showed a certain level of reduction in the cell viability. The IC50 value of MG is 16.94 mg/mL. The effects of MG in cell viability were evaluated previously with different cell lines and found to have cytoprotective effect or no adverse effects in cell viability77, 78.

Among these phenolic compounds, only MG showed QS inhibition. There are many mechanisms by which AHLs can be inactivated79. It was found in previous studies that changing in the length of the acyl chain of AHL and/or substitution of the 3-oxo group with hydroxyl or methylene reduced the autoinducing activity80. Addition of a phenyl group to the acyl chain terminus resulted in compounds with antagonist activity80. Moreover, the substitutions to the HSL resulted in loss of activity presumably due to loss of autoinducer-receptor binding80. One or more than one of the above mentioned mechanisms may employ in the case of QS inhibition of MG. The result in this study predicts that the galloyl moiety may be the basic structure for QS inhibition and the attachment of methyl ester (COOCH3) in carbon 1 position possibly essential to exert the effect. This speculation is also supported by Pimenta et al.34. The galloyl moiety without methyl ester in that position may not produce QS inhibition as there was no QS inhibition by gallic acid (Fig. 1F) in another study57. It is predicted that the replacement of hydrogen ion from the carboxyl group of gallic acid with other functional groups and/or side chain may initiates the quorum sensing inhibitions against P. aeruginosa which were observed in epigallocatechin gallate, ellagic acid and tannic acid81. We hypothesized that derivatives of MG may also have QS inhibition potential as some derivatives are reported for biofilm inhibition in another study34.

This is the first report on the anti-QS properties of MG against P. aeruginosa. MG can interfere with the QS of C. violaceum and P. aeruginosa, and modulate the occurrence of QS-associated virulence factors, which are crucial to develop new antimicrobials and/or improve the efficacy of existing antimicrobials and to reduce the pathogenicity associated with these bacteria. Moreover, this study determined the molecular mechanism of the QS inhibition of MG in P. aeruginosa. MG showed the down-regulation of autoinducer synthase (lasI and rhlI) and cognate receptor (lasR and rhlR) genes of P. aeruginosa (PAO1). All the findings of this study suggest that methyl gallate can be a safe and potential tool to combat virulence of C. violaceum and P. aeruginosa in healthcare environment or as a medication to treat C. violaceum and P. aeruginosa infections in the future.

Methods

MIC and MBC Assays

MIC assays were performed according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines for determining the antimicrobial activity of selected phenolic compounds (MG, pyrogallol, pyrocatechol, resorcinol and phloroglucinol)82. Overnight cultures of C. violaceum (ATCC12472, ATCC31532 and CV026), and P. aeruginosa (PAO1) were grown in lysogeny broth (LB). Cultures were diluted to a final inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in 96-well microtiter plates, compounds were added with appropriate concentrations and MIC was determined after 18 h incubation at 35 °C. MBCs were determined according to our previously published report37, 83. All of the QS assays and anti-virulence assays were performed at concentrations lower than the MIC values known as sub-inhibitory concentrations to ascertain that there was no inhibition.

Qualitative Anti-QS Activity

Standard disk–diffusion assay was used to detect anti-QS activity of the 5 phenolic compounds utilizing biomonitor strain, C.violaceum (ATCC12472) by slightly modifying a previously reported method84. C. violaceum ATCC12472 was poured on molten LB agar medium in plastic petri dish (90 × 15 mm) to make 5 × 106 CFU/mL. 60 μL of each compounds (15, 30 and 60 μg/60 μL) to be tested were pipetted on sterile paper disks, air dried and placed on solidified agar. They were incubated overnight at 30 °C, and examined for violacein production. QS inhibition was determined by a colorless, opaque, but viable halo around the disks.

Quantitative Anti-QS Activity

Quantitative evaluation of QS inhibition of phenolic compounds were carried out based on their ability to inhibit the production of purple violacein pigment by C. violaceum ATCC12472 according to previously reported methods85, 86. The bacterial strain was cultured aerobically in LB at 30 °C with or without the addition of sub-MIC concentrations of phenolic compounds. Furanone (10 μg/mL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as QSI-positive controls. One milliliter of an overnight culture of C. violaceum was centrifuged (13,793 g, 10 min) to precipitate the insoluble violacein. The culture supernatant was discarded and the pellet was evenly re-suspended in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The solution was centrifuged (13,793 g, 10 min) to remove the cells and the violacein was quantified at a wavelength of 585 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The percentage of violacein inhibition was calculated by following the formula85:

Effects of MG on the modulation of AHL synthesis and its activity

The agar diffusion double ring assay was performed for qualitative determination of the effect of MG on the inhibition of AHL synthesis (Set-B) and on the modulation of AHL activity (Set-A) using C. violaceum (CV) bioassay system (Supplementary Table 1) as described in Supplementary Fig. 4 and in published articles8, 55, 87.

In quantitative determination, the effect of MG on AHL synthesis and their activity were determined by slightly modifying a previously reported method16, 87. C. violaceum ATCC31532 was incubated in the presence of MG (1–16 μg/mL) for 48 h at 32 °C. The cultures were then centrifuged (5,223 g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was sterile-filtered. The filtrate containing AHL was extracted from the cell free supernatant (5 mL) using dichloromethane (3:1 v/v) and evaporated under vacuum at 45 °C. The isolated AHL was suspended in sterile LB and CV026 was inoculated, and incubated for 24 h at 32 °C. The cultures were subsequently assayed for violacein production as described in “Quantitative Anti-QS Activity” section.

For determining the effect of MG on AHL activity, AHL overproducer strain ATCC31532 was grown for 48 h at 32 °C. The culture was then centrifuged (5,223 g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was sterile-filtered. The AHL was extracted from filtered supernatant as stated above and supplemented with LB that contained MG (2–32 μg/mL). AHL biosensor strain CV026 was inoculated in AHL containing LB and incubated for 24 h at 32 °C. The bacterial cultures were centrifuged, then the pelleted cells were lysed with 0.1% SDS and the violacein was extracted in DMSO, and the absorbance read as described above.

Effects of phenolic compounds on swarming motility

The swarming motility of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) in presence of phenolic compounds was determined according to a previously described method37, 47. LB agar plates containing agar (0.50% w/v) and glucose (0.50% w/v) were used for the motility inhibition assay. Molten agar plates were supplemented with 1/2 × MIC of all these compounds. A non-supplemented drug free-plate was employed as the negative control, and furanone (10 μg/mL) supplemented plate was used as positive control. A single colony of P. aeruginosa was inoculated in the center of each plate using a toothpick, and then they were incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. The swarm zone diameters were measured using calibrated digital slide calipers (Mitotoyo, Japan), and photographs of the plates were captured. Molten agar plates were also supplemented with 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG to evaluate the concentration-dependent effects of MG on swarming motility.

Effects of MG on biofilm formation and viability

The inhibitory effect of MG on biofilm formation was determined by slightly modifying previously reported spectrophotometric methods88, 89. Briefly, test compounds were supplemented with trypticase soy broth (TSB) to three separate wells in 96-well microplate for each concentration, so that the final concentration would be 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG after inoculation of bacteria. The 18 h cultures of P. aeruginosa incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm were diluted with fresh TSB, and added to the designated wells which will be 1 × 106 CFU/mL after inoculation. Optical density at 600 nm was measured immediately after inoculation and after 24 h incubation at 37 °C to monitor planktonic cell growth. To determine the amount of biofilm formation, supernatant from the microplate wells was gently removed and the wells were washed thrice with sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.2) using a multichannel pipette. The remaining adherent biofilms were fixed by 200 μL of 99% methanol for 20 min, and was then stained with 100 μL of a 0.2% (w/v) crystal violet solution for 15 min at room temperature. The excess stain was removed from the wells by rinsing four times with PBS, and then 100 μL of 95% ethanol was added to extract the crystal violet in solution from the biofilm. The OD of the extracted crystal violet was then measured, yielding a measure of biofilm formation (relative to the control). For optical imaging, crystal violet stained biofilms were washed with sterile PBS and no ethanol extraction was performed. Measurements were performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times.

Previously reported biofilm viability assay methods were utilized to evaluate the effect of MG on the viability of biofilm produced by P. aeruginosa 37, 90. In brief, 2 mL of the sterile TSB broth was taken in Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chambered Coverglass (ThermoScientific, USA), and P. aeruginosa culture was inoculated to the broth to give 1 × 106 CFU/mL. The cultures of P. aeruginosa in Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chambered Coverglass were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C to produce biofilms. The broth media was changed every 24 h. After incubation, the Chambered Coverglass were rinsed with 1× PBS, and then 2 mL of sterile TSB containing 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG were added. They were again incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h exposure to MG, the biofilms were rinsed with sterile double-distilled water (DDW) and stained with BacLight live/dead stain (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA 02451, USA). Confocal microscopy was used to scan the viable and nonviable biofilms. Imaging was performed in a ZEISS LSM 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, IL 61801, USA), with 488 nm excitation and 560–600 nm emission range. Both image acquisition and subsequent manipulation were performed using ZEN 2009 software. The untreated biofilm was used as control.

Effects of MG on elastase activity

Elastase activity was measured by modifying the methods previously described55. Briefly, P. aeruginosa (PAO1) grown in the presence and absence of MG. One milliliter of 0.5% elastin-congo red solution (in 10 mM PBS) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) were mixed with 200 μL of P. aeruginosa culture supernatant fluids and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h in a water bath. The samples were then vortexed and centrifuged (118 g, 10 min, 10 °C) to remove insoluble elastin-congo red. The OD of the supernatant fluids from both the control and treated samples was measured at 494 nm. The percent change in OD was then calculated to determine the decrease in elastase activity. Activity was expressed as change in OD per μg of protein.

Effects of MG on total proteolytic activity

Total proteolytic activity of the cell-free supernatant fluid of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) culture cultivated in the presence and absence of MG was estimated according to a method described earlier55. Briefly, 100 μL of culture supernatant fluid was mixed with 900 μL of 0.5% azocasein (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) solution prepared in 50 mM Tris buffer containing 2 mM CaCl2. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, 15% TCA (300 μL) was added to stop the reaction, and then it was centrifuged (5,223 g, 10 min, 4 °C). The OD of the supernatant fluids from both the control and treatment samples was measured at 440 nm. The percent change in OD was then calculated from the OD values.

Effects of MG on LasA staphylolytic activity

LasA protease activity was determined by measuring the ability of P. aeruginosa (PAO1) culture supernatant fluid to lyse boiled S. aureus cells63, 70. A 30 mL volume of an overnight S. aureus culture was boiled for 10 min, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g. The resulting pellet was re-suspended in 10 mM Na2PO4 (pH 4.5) to an OD value of approximately 0.8 at 600 nm. A 100 μL aliquot of P. aeruginosa LB medium culture supernatant with or without MG was added to 900 μL of a boiled S. aureus suspension, and the OD was determined after 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min at 600 nm. Activity was expressed as the change in the OD/hour per μg of protein.

Effects of MG on pyocyanin production

Pyocyanin was extracted from P. aeruginosa culture supernatant and measured by the method as described earlier61. Briefly, a 5 mL sample of culture grown for 24 h in broth medium containing the test material was centrifuged, and the supernatant extracted with 3 mL of chloroform and then re-extracted into 1 mL of 0.2 M HCl to give a pink to deep red solution. The OD of this solution was measured at 520 nm. Concentrations expressed as pyocyanin produced in μg/mL of culture supernatant were determined by multiplying the OD520 by 17.072.

Effects of MG on exopolysaccharide production

P. aeruginosa (PAO1) grown in the presence and absence of MG were centrifuged and the resulting supernatant was filtered. Three volumes of chilled 100% ethanol were added to the filtered supernatant and incubated overnight at 4 °C to precipitate the exopolysaccharide (EPS)91, 92. EPS was then extracted and quantified by measuring sugars as below. A 1 mL aliquot of a carbohydrate solution is mixed with 0.5 mL of 5% aqueous solution of phenol in a test tube. Subsequently, 2.5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid added rapidly to the mixture. After allowing the test tubes to stand for 10 min, they are vortexed for 30 s and placed for 20 min in a water bath at room temperature for color development. Then, OD at 490 nm is recorded on a spectrophotometer. Reference solutions are prepared in identical manner as above, except that the 1 mL aliquot of carbohydrate is replaced by distilled water.

Effects of MG on rhamnolipid production

One of the most widely used methods for ramnolipid quantification is the orcinol test93, 94. Briefly, 300 μL supernatant from PPB (containing 2% glycerol) culture was extracted twice using 600 μL diethyl ether. The ether layer was transferred to a new tube and allowed to evaporate. Residues were dissolved in a solution of 100 μL H2O, 100 μL 1.6% orcinol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), and 800 μL 60% H2SO4. After heating for 30 min at 80 °C, tubes were cooled at room temperature for 15 min, and the OD was measured at 421 nm. Rhamnose concentrations were determined using the standard curve equation, y = 0.0033x − 0.0077 and concentrations of rhamnolipids were calculated by multiplying rhamnose values by a coefficient of 2.5, as previously described66.

Effects of MG on the expression of quorum sensing genes

P. aeruginosa (PAO1) was treated with 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/mL of MG for 16 h with the supplementation of 100 μM autoinducer (3-oxo-C12-HSL), and total RNA was extracted according to the protocol for TRIZOL reagent (Sigma). The purity of RNA was confirmed and concentration (μg/mL) was calculated by measuring OD at 260 and 280 nm using a U-2800 spectrophotometer (Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of RNA by using RNA to cDNA EcoDry Premix (Oligo dT) (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Seoul 153–779, Republic of Korea) according to the supplied protocol. The expressions of target genes were detected by performing real-time PCR with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. To each PCR tubes (TLS0851, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Herts HP27DX, United Kingdom), 12.5 μL of SYBR Select Master Mix for CFX (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA 94404, USA), 1 μL of forward primer (10 pmol) and 1 μL of reverse primer (10 pmol) of target gene, 9.5 μL of RNase-free water and 1 μL of cDNA were added, mixed by pipetting and spined down. The real time PCR reaction was accomplished in CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Irvine, CA 92618, USA) with 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 15 s and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s. mRNA expressions were normalized using β-actin. All mRNA expressions were expressed in relation to the average expression of the non-treated group (100%).

Cell viability assay

The in vitro cytotoxicity of MG was determined by means of reported methods of MTT assay with slight modification95, 96. In brief, the RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (Korean Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Republic of Korea) were cultured in 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-supplemented RPMI 1640 medium, at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). The cells (2 × 104 cells/mL) were acclimated for 24 h onto 96-well plates containing 100 μL of RPMI medium with the added substances mentioned above. Afterward, the cells were treated with 0, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.50 and 25.00 mg/mL of MG. Twenty microliter of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added in each well after 24 h of treatment, and incubated again for 4 h. Then, the supernatant was discarded, and DMSO (200 μL) was supplemented to each well. The cells in DMSO were placed at room temperature for 30 min to completely solubilize the formazan crystals. The optical density was measured at 570 nm. The cells not treated with any drugs were assigned as control. The cell viability (%) was calculated by the following formula and the inhibitory concentration fifty percent (IC50) of MG was determined by using Graphpad prism 5.0 (California, USA).

Viable Cells (%) = (OD of drug-treated sample/OD of non-treated sample) × 100, where OD is the optical density97.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate assays. SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was utilized for statistical analysis. Values were appraised by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following F-test. P-values of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistical significant which are illustrated by different alphabets.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1A2B4013507), in part by the “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development” (Project no. PJ01128901), Rural Development Administration, in part by Korean Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology (IPET) through Technology Commercialization Support Program (314082-3), the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and in part by the Daejeon IRPE project (R0004266) through the Research and Development for Regional Industry of the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, Republic of Korea. We cordially appreciate Prof. Robert JC McLean, who provided the required quorum sensing strains. This manuscript is based on part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation from Kyungpook National University.

Author Contributions

M.A.H. conceived and designed the experiments. M.A.H. and S.J.L. performed experiments, analyzed data and prepared manuscript draft. N.H.P., A.F.M. and B.T.B. were engaged in different experiments. J.W.K. and M.A.R. critically reviewed the manuscript. J.W.S. and S.C.P. were principal investigators for this study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10997-5

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Joo-Won Suh, Email: jwsuh@mju.ac.kr.

Seung-Chun Park, Email: parksch@knu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing: Its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. 2012;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J, Winans SC. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc Natl AcadSci. 1999;96:4832–4837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J, Winans SC. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:1507–1512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.deOca-Mejia MM, Castillo-Juarez I, Martinez-Vazquez M, Soto-Hernandez M, Garcia-Contreras R. Influence of quorum sensing in multiple phenotypes of the bacterial pathogen Chromobacterium violaceum. Pathog Dis. 2015;73:1–4. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftu019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.August PR, et al. Sequence analysis and functional characterization of the violacein biosynthetic pathway from Chromobacterium violaceum. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo-Juárez I, García-Contreras R, Velázquez-Guadarrama N, Soto-Hernández M, Martínez-Vázquez M. Amphypterygium adstringens anacardic acid mixture inhibits quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors of Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClean KH, et al. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: Exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acyl homoserine lactones. Microbiology. 1997;143:3703–3711. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steindler L, Venturi V. Detection of quorum-sensing N-acyl homoserine lactone signal molecules by bacterial biosensors. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;266:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durán N, et al. Violacein: properties and biological activities. Biotechnol Appl Bioc. 2007;48:127–133. doi: 10.1042/BA20070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Q, et al. Identification of a small molecule that simultaneously suppresses virulence and antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep19141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: A transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Loughlin CT, et al. A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:17981–17986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316981110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria: A signaling mechanism involved in associations with higher organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:8789–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner VE, Bushnell D, Passador L, Brooks AI, Iglewski BH. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: Effects of growth phase and environment. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2080–2095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2080-2095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin H, et al. Tea polyphenols as an antivirulence compound disrupt quorum-sensing regulated pathogenicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep16158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antunes LC, Ferreira RB, Buckner MM, Finlay BB. Quorum sensing in bacterial virulence. Microbiology. 2010;156:2271–2282. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong YH, et al. Quenching quorum-sensing dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature. 2001;411:813–817. doi: 10.1038/35081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson T, Givskov M, Nielsen J. Quorum sensing inhibition: targeting chemical communication in gram-negative bacteria. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:3103–3115. doi: 10.2174/092986705774933425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishii S, et al. High-throughput screening of small molecule inhibitors of the Streptococcus quorum-sensing signal pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03567-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delago A, Mandabi A, Meijler MM. Natural quorum sensing inhibitors–small molecules, big messages. Isr. J. Chem. 2016;56:310–320. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201500052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo M, Gamby S, Zheng Y, Sintim HO. Small molecule inhibitors of AI-2 signaling in bacteria: state-of-the-art and future perspectives for anti-quorum sensing agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:17694–17728. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galloway WRJD, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden S, Welch M, Spring DR. Applications of small molecule activators and inhibitors of quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends. Microbiol. 2012;20:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattmann ME, Blackwell HE. Small molecules that modulate quorum sensing and control virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:6737–6746. doi: 10.1021/jo101237e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuster M, Sexton DJ, Diggle SP, Greenberg EP. Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing: from evolution to application. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;67:43–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy V, Adams BL, Bentley WE. Developing next generation antimicrobials by intercepting AI-2 mediated quorum sensing. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2011;49 doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen QH, Grove TL, Bookerb SJ, Greenberg EP. A high-throughput screen for quorum-sensing inhibitors that target acyl-homoserine lactone synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:13815–13820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313098110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sintim HO, Smith JA, Wang J, Nakayama S, Yan L. Paradigm shift in discovering next-generation anti-infective agents: targeting quorum sensing, c-di-GMP signaling and biofilm formation in bacteria with small molecules. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:1005–1035. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Defoirdt T, Pande GS, Baruah K, Bossier P. The apparent quorum-sensing inhibitory activity of pyrogallol is a side effect of peroxide production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2870–2873. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00401-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni N, Choudhary G, Li M, Wang B. Pyrogallol and its analogs can antagonize bacterial quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1567–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiran MD, et al. Discovery of a quorum-sensing inhibitor of drug-resistant Staphylococcal infections by structure-based virtual screening. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1578–1586. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaubal R, Deshpande VH, Deshpande NR. Methyl gallate, the medicinally important compound: a review. Electron J Environ Agric Food Chem. 2005;4:956–962. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan WW, Yuan GQ, Li QQ, Lin W. Antibacterial mechanisms of methyl gallate against Ralstonia solanacearum. Australas Plant Pathol. 2014;43:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13313-013-0234-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pimenta ADL, et al. Synthetic organic compounds with potential for bacterial biofilm inhibition, a path for the identification of compounds interfering with quorum sensing. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2013;42:519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y. The anti-oxidation and anti-microbial activities of tea polyphenols and its increased reagents. J Biol. 2007;24:54–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hossain MA, Park JY, Kim JY, Suh JW, Park SC. Synergistic effect and antiquorum sensing activity of Nymphaea tetragona (water lily) extract. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/562173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hossain MA, et al. Modulation of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors by Nymphaea tetragona (water lily) extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morohoshi T, Kato M, Fukamachi K, Kato N, Ikeda T. N-acylhomoserine lactone regulates violacein production in Chromobacterium violaceum type strain ATCC12472. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;279:124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devescovi G, et al. Negative regulation of violacein biosynthesis in Chromobacterium violaceum. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HS, Lee SH, Byun Y, Park HD. 6-Gingerol reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence via quorum sensing inhibition. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep08656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latifi A, Foglino M, Tanaka K, Williams P, Lazdunski A. A hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa link the transcriptional activators LasR and RhlR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;21:1137–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pesci EC, et al. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:11229–11234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKnight KH, Iglewski BH, Pesci EC. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal regulates rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2702–2708. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2702-2708.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li LL, Malone JE, Iglewski BH. Regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulator VqsR. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:4367–4374. doi: 10.1128/JB.00007-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi Y, et al. Growth phase-differential quorum sensing regulation of anthranilate metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Cells. 2011;32:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-2322-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalia VC. Quorum sensing inhibitors: An overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:224–245. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norizan SNM, Yin WF, Chan KG. Caffeine as a potential quorum sensing inhibitor. Sensors. 2013;13:5117–5129. doi: 10.3390/s130405117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh BR, et al. Mycofabricated biosilver nanoparticles interrupt Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing systems. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep13719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopu V, Meena CK, Murali A, Shetty PH. Petunidin as a competitive inhibitor of acylated homoserine lactones in Klebsiella pneumonia. RSC Adv. 2016;6:2592–2601. doi: 10.1039/C5RA20677D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ooka K, et al. Piericidins, Novel Quorum-sensing inhibitors against Chromobacterium violaceum CV026, from Streptomyces sp. TOHO-Y209 and TOHO-O348. Open J Med Chem. 2013;3:93–99. doi: 10.4236/ojmc.2013.34012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinelli D, Grossmann G, Séquin U, Brandl H, Bachofen R. Effects of natural and chemically synthesized furanones on quorum sensing in Chromobacterium violaceum. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hentzer M, et al. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology. 2002;148:87–102. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raffa RB, et al. Bacterial Communication (“Quorum Sensing”) via ligands and receptors: A novel pharmacologic target for the design of antibiotic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:417–423. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schauder S, Bassler BL. The languages of bacteria. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1468–1480. doi: 10.1101/gad.899601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mihalik K, Chung DW, Crixell SH, McLean RJC, Vattem DA. Quorum sensing modulators of Pseudomonas aeruginosa characterized in Camellia sinensis. Asian J Tradit Med. 2008;3:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tremblay J, Déziel E. Improving the reproducibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa swarming motility assays. J Basic Microb. 2008;48:509–515. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniels R, Vanderleyden J, Michiels J. Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:261–289. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oura H, et al. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa swarming motility by 1-naphthol and other bicyclic compounds bearing hydroxyl group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:2808–2818. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04220-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta R, Schuster M. Quorum sensing modulates colony morphology through alkyl quinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zegans ME, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exopolysaccharide Psl Promotes resistance to the biofilm inhibitor Polysorbate 80. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4112–4122. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00373-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naik DN, Wahidullah S, Meena RM. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by marine invertebrate derived Streptomyces sp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2013;56:197–207. doi: 10.1111/lam.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassett DJ, Charniga L, Bean K, Ohman DE, Cohen MS. Response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to pyocyanin: mechanisms of resistance, a manganese-cofactored superoxide dismutase. Infect Immun. 1992;60:328–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.328-336.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kong KF, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional factor. That regulates expression of AmpC and PoxB β-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4567–4575. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4567-4575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen PØ, et al. Rapid necrotic killing of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is caused by quorum-sensing-controlled production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2007;153:1329–1338. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003863-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caiazza NC, Shanks RMQ, O’Toole GA. Rhamnolipids modulate swarming motility patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J bacterial. 2005;187:7351–7361. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7351-7361.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang YX, et al. A New Quorum-sensing inhibitor attenuates virulence and decreases antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Microbiol. 2012;50:987–993. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarabhai S, Sharma P, Capalash N. Ellagic acid derivatives from Terminalia chebula Retz. downregulate the expression of quorum sensing genes to attenuate Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 virulence. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gi M, et al. A Drug-repositioning screening identifies pentetic acid as a potential therapeutic agent for suppressing the elastase-mediated virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:7205–7214. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03063-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmidberger A, Henkel M, Hausmann R, Schwartz T. Influence of ferric iron on gene expression and rhamnolipid synthesis during batch cultivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:6725–6737. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adonizio A, Kong KF, Mathee K. Inhibition of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factor production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by South Florida plant extracts. Antimicrob Agents Chemothe. 2008;52 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00612-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bala A, Kumar R, Harjai K. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by azithromycin and its effectiveness in urinary tract infections. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:300–306. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.025387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davies DG, et al. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dekimpe V, Deziel E. Revisiting the quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The transcriptional regulator rhlR regulates lasR-specific factors. Microbiology. 2009;155:712–723. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.022764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeune KSL, et al. Impaired functions of macrophage from cystic fibrosis patients: CD11b, TLR-5 decrease and sCD14, inflammatory cytokines increase. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhai Z, et al. Echinacea increases arginase activity and has anti-inflammatory properties in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, indicative of alternative macrophage activation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maurya MR, et al. Analysis of inflammatory and lipid metabolic networks across RAW264.7 and thioglycolate-elicited macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2525–2542. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Crispo JA, et al. Protective effects of polyphenolic compounds on oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:429–438. doi: 10.1139/Y09-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cha SH, Suh CK. Heme oxygenase-1 mediated protective effect of methyl gallate on cadmium-induced cytotoxicity in cultured mouse mesangial cells. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2010;6:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s13273-010-0019-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang JJ, Han JI, Zhang LH, Leadbetter JR. Utilization of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum signals for growth by a soil Pseudomonad and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. App. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:5941–5949. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5941-5949.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith KM, Bu Y, Suga H. Library screening for synthetic agonists and antagonists of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa autoinducer. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:563–571. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tan YP, Chan EWC, Lim CSY. Potent Quorum sensing inhibition by methyl gallate isolated from leaves of Anacardium occidentale L. (cashew) Chiang Mai J Sci. 2015;42:650–656. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). M100–S17, 17th Informational Supplement, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Wayne, PA, USA (2007).

- 83.Ramadoss NS, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of trans-translation have broad-spectrum antibiotic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:10282–10287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302816110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Srivastava A, Singh BN, Deepak D, Rawat AKS, Singh BR. Colostrum hexasaccharide, a novel Staphylococcus aureus quorum-sensing inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2169–2178. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03722-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chenia HY. Anti-quorum sensing potential of crude Kigelia Africana fruit extracts. Sensors. 2013;13:2802–2817. doi: 10.3390/s130302802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li G, et al. Punicalagin inhibits Salmonella virulence factors and has anti-quorum-sensing potential. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:6204–6211. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01458-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vattem DA, Mihalik K, Crixell SH, McLean RJC. Dietary phytochemicals as quorum sensing inhibitors. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]