Abstract

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) function in translational machinery and further serves as a source of short non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). tRNA-derived ncRNAs show differential expression profiles and play roles in many biological processes beyond translation. Molecular mechanisms that shape and regulate their expression profiles are largely unknown. Here, we report the mechanism of biogenesis for tRNA-derived Piwi-interacting RNAs (td-piRNAs) expressed in Bombyx BmN4 cells. In the cells, two cytoplasmic tRNA species, tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG, served as major sources for td-piRNAs, which were derived from the 5′-part of the respective tRNAs. cP-RNA-seq identified the two tRNAs as major substrates for the 5′-tRNA halves as well, suggesting a previously uncharacterized link between 5′-tRNA halves and td-piRNAs. An increase in levels of the 5′-tRNA halves, induced by BmNSun2 knockdown, enhanced the td-piRNA expression levels without quantitative change in mature tRNAs, indicating that 5′-tRNA halves, not mature tRNAs, are the direct precursors for td-piRNAs. For the generation of tRNAHisGUG-derived piRNAs, BmThg1l-mediated nucleotide addition to −1 position of tRNAHisGUG was required, revealing an important function of BmThg1l in piRNA biogenesis. Our study advances the understanding of biogenesis mechanisms and the genesis of specific expression profiles for tRNA-derived ncRNAs.

INTRODUCTION

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are ∼70−90-nucleotides (nt) of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that are universally expressed in all organisms and function as fundamental adapter components of translational machinery to translate mRNA codons into amino acids of proteins (1,2). Besides their role in translation, tRNAs further serve as substrates for shorter ncRNAs. In many organisms, specific ncRNAs are produced from mature tRNAs or their precursor molecules (pre-tRNAs) to serve as functional molecules, rather than random degradation products (3–8). In general, tRNA-derived ncRNAs are classified into two groups: tRNA halves and tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs). tRNA halves range either from the 5′-end to the anticodon-loop (5′-half) or from the anticodon-loop to the 3′-end (3′-half) of a mature tRNA, and their production is triggered by stresses and sex hormone signaling pathways (6,9,10). 5′-tRNA halves have been shown to be functional molecules that regulate translation, promote stress granule formation and cell proliferation, and are involved in neurodegenerative diseases and aging (10–16). Generally shorter than tRNA halves, tRFs originate from the 5′-part (5′-tRF), 3′-part (3′-tRF) or wholly internal part (i-tRF) of mature tRNAs or other precursor sequences (3–8,17). They show differential but specific expression profiles in different cells and tissues and are involved in many biological processes, such as cell proliferation, tumor suppression and priming of viral reverse transcriptase (3–8,17). Although tRF expressions might be able to serve as indicators for biological states, it is still unknown as to how the specific expression profiles of tRFs are shaped.

The functional significance of tRFs is particularly evident by their involvement in the pathway of small regulatory RNAs bound by Argonaute family proteins (7). It has been shown that a variety of tRFs are selectively and differentially loaded onto the Ago subclade of the Argonaute family in human cells (17–24). These types of Ago-loaded tRFs are further known to function as microRNAs (miRNAs) by repressing the expression of their complementary target mRNAs. For example, Ago-bound 3′-tRFLysUUU (3′-tRF derived from tRNALysUUU) silences HIV-1 in MT4 T-cells (25), while Ago-bound 3′-tRFGlyGCC modulates DNA damage response by targeting RPA1 in human B cells (26). The presence of Ago-bound tRFs has also been reported for many other organisms, such as the mouse (27), Drosophila (28,29), Bombyx (30) and in plant (31). However, despite the widespread presence and evident functional significance of Ago-bound tRFs as miRNAs, their biogenesis mechanisms remain largely elusive. Although both Dicer-dependent and independent biogenesis pathways have been suggested (18,19,21,22,26,28,32), the molecular mechanisms underlying the selection of tRNAs for miRNA biogenesis and specific and differential Ago-loading of each of the tRFs is unknown.

Piwi proteins, the other Argonaute subclade, are predominantly expressed in the germline and are associated with ∼26−31-nt Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) to regulate transposons and other targets for maintaining genome integrity (33,34). Piwi proteins, like Ago proteins, have also been observed interacting with tRFs in various organisms, such as human (35), marmoset (36), Drosophila (37–39), and Trypanosoma (40). The functional significance of Piwi-bound tRFs was shown in Tetrahymena where TWI12 was tightly bound to tRFs, and played crucial roles in stimulating Xrn2 exonuclease for nuclear RNA processing (41,42). However, as in the case of Ago-loaded tRFs, the biogenesis mechanisms producing Piwi-bound tRFs remain unknown. Only specific species of tRFs are selectively loaded onto Piwi proteins as piRNAs. For example, 5′-tRFGluCUC is predominantly loaded onto the Piwi protein in marmoset testes (36), while 5′-tRFGluUUC and i-tRFGluUUC are abundant as Piwi-bound tRFs in Drosophila Kc167 cells (39). The molecular mechanisms underlying the selection of tRNAs for piRNA biogenesis and specific Piwi-loading of different tRF species in different organisms are completely unknown.

To unravel the emerging complexities of tRF biology, it is imperative to understand the tRF biogenesis mechanism that induces specific expression profiles of tRFs. Here we report the characterization of the expression profile and biogenesis mechanism of tRNA-derived piRNAs (td-piRNAs) by utilizing BmN4 cells, a culturable germ cell line derived from Bombyx mori ovary. BmN4 cells possess fully functional primary and secondary piRNA biogenesis pathways, and express both Bombyx Piwi proteins, Siwi and BmAgo3, as well as their bound piRNAs (43). Because of the scarcity of piRNA-expressing culturable germ cell line, BmN4 cells have been used often to elucidate the piRNA biogenesis mechanism and its required protein factors (44–48). Our analyses of Siwi- and BmAgo3-bound piRNAs showed that 5′-tRFs of only specific tRNA species are abundantly expressed as Piwi-bound td-piRNAs. Furthermore, unraveling expression profiles of 5′-tRNA halves revealed a previously uncharacterized link between the expressed species of tRNA halves and td-piRNAs. Our additional experimental validations suggest a model in which 5′-tRNA halves, not mature tRNAs, are the direct precursors for td-piRNAs. These results explain why specific expression profiles of td-piRNAs are governed in the cells. Our study advances the understanding of the biogenesis mechanisms for the Argonaute-interacting, tRNA-derived regulatory RNAs and provides the example of how specific tRF expression profiles are shaped.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BmN4 cell culture, RNA isolation, enzymatic treatment and β-elimination

BmN4 cells were cultured at 27°C in Insect-Xpress medium (Lonza). RNA isolation, enzymatic treatment, and β-elimination were performed as previously described (10,44). In brief, total RNA was isolated using the TRIsure reagent (Bioline). To investigate the 3′-terminal structures of 5′-tRNA halves, total RNA was treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP; New England Biolabs) or T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 PNK; New England Biolabs), and then subjected to qRT-PCR detection of 5′-tRNA halves and piRNAs (see below section). To investigate the 3′-terminal structures of 3′-tRNA halves, total RNA was first subjected to deacylation treatment, followed by a β-elimination reaction. For deacylation, total RNA was incubated in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) at 37°C for 40 min. For β-elimination, total RNA was first incubated with 10 mM NaIO4 at 0°C for 40 min in the dark. 1 M rhamnose (1/10 volume) was then added to quench unreacted NaIO4 and incubated at 0°C for 30 min. Subsequently, β-elimination was performed by adding an equal volume of 2 M Lys-HCl (pH 8.5) and incubating at 45°C for 90 min. The treated total RNA was then subjected to Northern blot detection of 3′-tRNA halves (see below section).

Quantification of 5′-tRNA halves and td-piRNAs by TaqMan qRT-PCR

TaqMan qRT-PCR quantification of 5′-tRNA halves and td-piRNAs was performed according to our previously-described tRNA halves’ quantification method (10) with modifications (Supplementary Figure S1). Total RNA was at first incubated with 10 mM NaIO4 at 0°C for 40 min in the dark to disrupt 3′-OH ends of RNAs; 5′-tRNA halves and piRNAs survive the treatment because of the presence of a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (cP) and 2′-O-methyl modification at the 3′-end, respectively. For quantification of 5′-tRNA halves (5′-halfAspGUC and 5′-halfHisGUG), total RNA was then treated with T4 PNK to dephosphorylate the 3′-end of 5′-tRNA halves. For quantification of td-piRNAs (td-piRAspGUC and td-piRHisGUG), the NaIO4-treated RNA was subjected to the next step without any pretreatment. For both cases, 100 ng of the treated RNAs were subjected to a ligation reaction (10-μL reaction mixture) with 20 pmol of a 3′-RNA adaptor (5′-P-GAACACUGCGUUUGCUGGCUUUGAGAGUUCUACAGUCCGACGAUC-ddC-3′) using T4 RNA Ligase (T4 Rnl; Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, 1 ng of ligated RNA was subjected to TaqMan qRT-PCR (10-μL reaction mixture) using the One Step PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (Clontech), 400 nM of a TaqMan probe targeting the boundary of the targeted RNA and 3′-RNA adaptor, and 2 pmol each of specific forward and reverse primers. With the StepOne Plus Real-time PCR machine (Life Technologies), the reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 5 min and then 95°C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s. The quantified RNA levels were normalized to the levels of Bombyx 5S rRNA quantified by qRT-PCR using a stem-loop reverse primer (see below section). The sequences of the primers and TaqMan probes are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Northern blot

Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (44). Briefly, 5 μg of total RNA were resolved by 12% PAGE containing 7 M urea using the SE400 Electrophoresis Unit (Hoefer) or sequencing system aluminum 2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (GE Healthcare), and hybridized to 5′-end-labeled antisense probes whose sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

cP-RNA-seq to selectively amplify and sequence 5′-tRNA halves

cP-RNA-seq was performed as described previously (10,49). Briefly, ∼30–40-nt RNAs were gel-purified from BmN4 total RNA and treated with CIP. After phenol-chloroform purification, the RNAs were oxidized by incubation in 10 mM NaIO4 at 0°C for 40 min in the dark, followed by ethanol precipitation. The RNAs were then treated with T4 PNK. After phenol–chloroform purification, directional ligation of adapters, cDNA generation, and PCR amplification were performed using the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Prep kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The amplified cDNAs were sequenced using Illumina hiSeq2000 system at the Functional Genomics Core at the University of Pennsylvania.

Bioinformatics analyses

To identify td-piRNA sequences expressed in BmN4 cells, Bombyx tRNA reference sequences were extracted by applying tRNA scan program (50) for Bombyx mori genome (http://www.silkdb.org/silkdb/). Variant sequences of Bombyx cytoplasmic (cyto) tRNAAspGUC, tRNAHisGUG, tRNAGluUUC, and tRNAGluCUC are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. The six piRNA libraries [1: Siwi-piRNAs; 2: BmAgo3-piRNAs; 3: Siwi-piRNAs from Rluc-(control) depleted cells; 4: Siwi-piRNAs from BmPapi-depleted cells; 5: BmAgo3-piRNAs from Rluc-depleted cells; 6: BmAgo3-piRNAs from BmPapi-depleted cells; DDBJ #DRA002562], obtained from Siwi- or BmAgo3-immunoprecipitates of BmN4 cells in our previous study (44), were then mapped to the tRNA reference sequences using SHRiMP2 (51), which allowed a 4% mismatch rate (no insertions or deletions allowed), soft clipping, and non-unique mappings. In the subsequent analyses shown in Figure 1, we focused on the reads over 1 rpm.

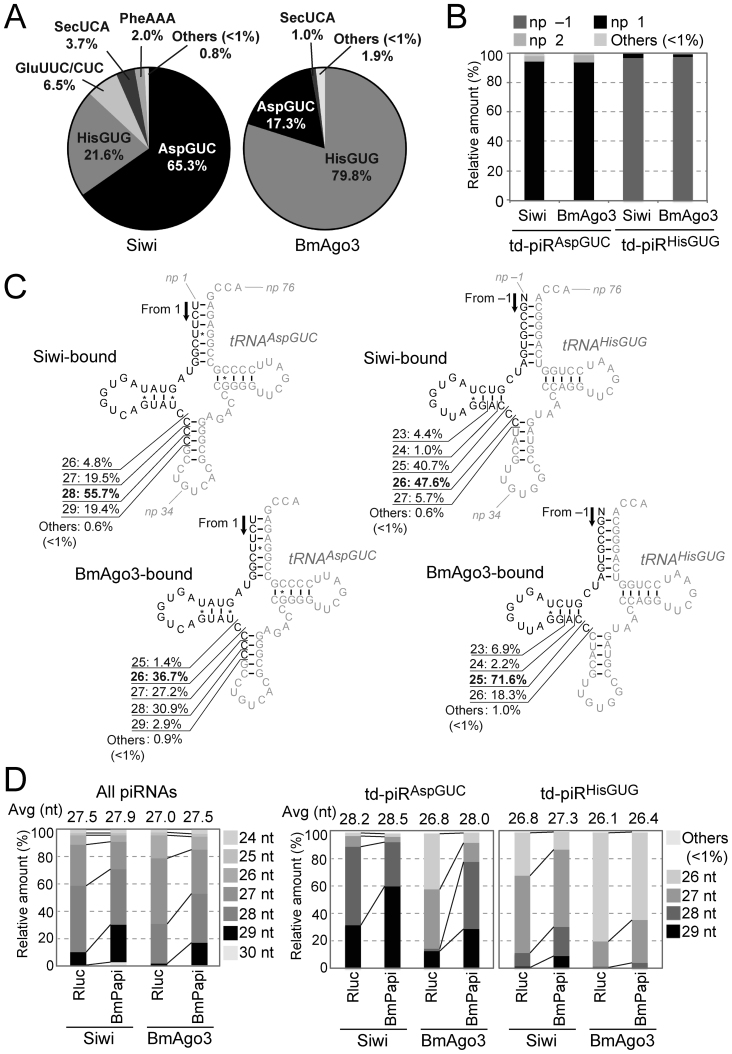

Figure 1.

Identification of td-piRNAs in BmN4 cells. (A) BmN4 Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound piRNAs were mapped against Bombyx mori tRNA sequences. Among the tRNA-mapped piRNA reads, pie charts show the percentages of the reads derived from respective cyto tRNA species. (B) The 5′-terminal position of Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound td-piRAspGUC or td-piRHisGUG in the respective mature tRNA. Nucleotide positions (np) are indicated according to the nucleotide numbering system of tRNAs (2). (C) The regions from which td-piRAspGUC, starting from np 1, or td-piRHisGUG, starting from np –1, were derived are shown in black in the cloverleaf secondary structure of Bombyx cyto tRNAAspGUC-V1 (Supplementary Figure S2) and tRNAHisGUG. Non-piRNA-derived regions are shown in gray. (D) Read-length distribution of the Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound total piRNAs, td-piRAspGUC, or td-piRHisGUG identified in Rluc-depleted (control) or BmPapi-depleted BmN4 cells.

To identify 5′-tRNA halves expressed in BmN4 cells, the cP-RNA-seq-yielded library was analyzed. The library contains 54 054 137 raw reads and is publically available at NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (accession no. SRP107958). Prior to mapping, we used the cutadapt tool (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200) to remove the 3′-adapter sequence (5′-TGGAATTCTCGGGTGCCAAGG-3′). The adapter-removed sequences (52 806 536 reads) were mapped to Bombyx tRNA sequences as described above, resulting in 59.3% mapped ratio (31 338 554 reads were mapped to tRNAs). In the subsequent analyses shown in Figure 3, we focused on the reads over 1 rpm and over 30 nt in length, which in aggregate accounted for ∼99.2% of the mapped reads.

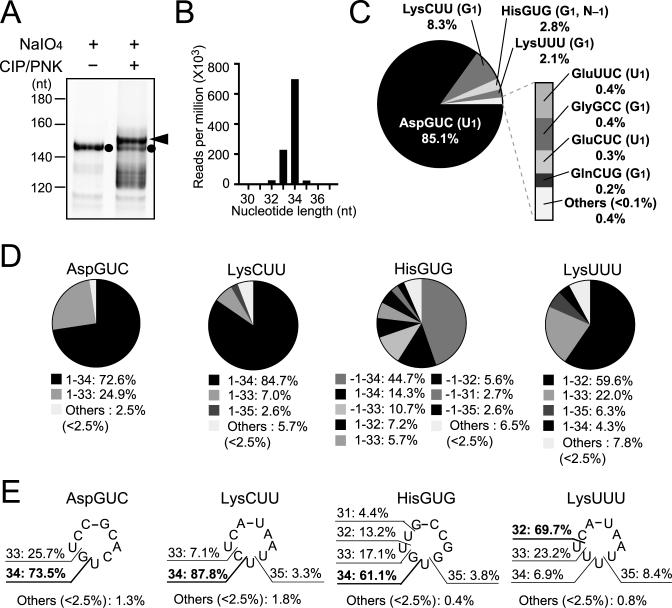

Figure 3.

Identification of 5′-tRNA halves in BmN4 cells by the cP-RNA-seq method. (A) BmN4 ∼30–40-nt RNAs were gel-purified and applied to cP-RNA-seq method. The full-procedure mainly amplified ∼153-bp cDNA products (5′-adapter, 55 bp; 3′-adapter, 63 bp; and therefore inserted sequences, ∼35 bp) as indicated by an arrowhead, while the procedure without CIP and T4 PNK treatments amplified ∼146-bp cDNA products (inserted sequences, ∼28 bp) as indicated by black circles. (B) Read-length distribution of the tRNA-mapped reads. (C) Pie chart showing the percentages of reads derived from respective cyto tRNA species. 5′-terminal nucleotides of each tRNA are shown in parenthesis. (D) Pie charts showing the mature tRNA regions from which the sequenced 5′-tRNA halves were derived. (E) The anticodon-loop cleavage sites were predicted based on the 3′-terminal positions of 5′-tRNA halves, and the percentages of the sites are shown.

RNAi knockdown of BmThg1l and BmNSun2 in BmN4 cells

From SilkBase (http://silkbase.ab.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cgi-bin/index.cgi), we retrieved the BGIBMGA002973-TA and BGIBMGA004408-TA GeneModel sequences as significant homologs to human THG1L (NP_060342.2) and NSUN2 (NP_060225.4) using tblastn algorism; these genes were named as BmThg1l and BmNSun2, respectively (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). RNAi knockdowns of BmThg1l and BmNSun2 in BmN4 cells was performed as described previously (44) with minor modifications. Briefly, to synthesize templates for the in vitro production of dsRNA, BmN4 total RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and reverse transcription was performed with random hexamer primers. The resultant cDNAs were used as templates for PCR with specific forward and reverse primers shown in Supplementary Table S3. The amplified DNAs containing T7 promoter sequence on both strands were used as templates in a T7 in vitro transcription system (MEGAscript T7, Ambion), followed by purification with MEGAclear (Ambion). The synthesized and purified dsRNA (6 μg) was transfected into 3 × 106 BmN4 cells using 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza). After culturing for 5 days, an identical dsRNA transfection was performed again. After culturing for another 2 days, to accelerate de novo synthesis of piRNAs, 6 μg of a pIZ-based plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged Siwi or BmAgo3 (44) were transfected using 30 μl of Escort IV Transfection Reagent (Sigma) into BmThg1l- or BmNsun2-depleted cells, respectively. After culturing for another 2 days, the cells were harvested for the analyses of piRNAs, tRNAs, tRNA halves and mRNAs. To confirm the efficiency of the RNAi knockdowns, the expression levels of targeted mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR using 2 × qPCR Master Mix (Bioland Scientific LLC) and the primers shown in Supplementary Table S4. BmRp49 was used as a control for normalization.

qRT-PCR using a stem-loop reverse primer

Two piRNAs (piR-1 and piR-2) and let-7 miRNA were quantified by qRT-PCR using a stem–loop reverse primer that is based on miRNA quantification by stem-loop qRT-PCR (52). By using StepOne Plus Real-time PCR machine (Life Technologies), the reaction mixture consisted of One-Step SYBR PrimeScriptª RT-PCR Kit II (Clontech) and the primers shown in Supplementary Table S5 was incubated at 16°C for 15 min, 42°C for 15 min, and then 95°C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s. 5S rRNA was used as a control for normalization.

RESULTS

Cytoplasmic tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG are rich sources of piRNAs in BmN4 cells

Our previous analyses, using BmN4 cells, detected the expression of piR-a, which is derived from the 5′-part of Bombyx cytoplasmic (cyto) tRNAAspGUC (10). The piR-a is a 5′-tRFAspGUC sharing an identical 5′-end with the mature tRNA and corresponding to the nucleotide position (np) 1–28 (np is according to the nucleotide numbering system of tRNAs (2)). Because piR-a was among the most abundant piRNA species detected in our previous piRNA sequencing (44), we hypothesized that tRNAs are rich sources of piRNAs in BmN4 cells. To explore the td-piRNA species, we mapped Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound piRNA sequences, previously identified by Illumina sequencing of the RNAs from Siwi- or BmAgo3-immunoprecipitates (44), to Bombyx tRNA sequences. Among the tRNA-mapped reads, we focused on RNA species with >1 reads per million (rpm). Among the total 52 species of Bombyx cyto tRNA isoacceptors, only a few cyto tRNA species were found to be major sources of Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound td-piRNAs (Figure 1A). The two species, cyto tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG, were particularly enriched as td-piRNA sources, comprising 86.9% or 97.1% of the total Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound td-piRNAs, respectively. Most td-piRAspGUC were derived from np 1–25∼29 of mature tRNAAspGUC (Figure 1B and C). As mature tRNAHisGUG is known to contain one extra evolutionally-conserved 5′-terminal nucleotide at np –1 (2,53), td-piRHisGUG was derived mainly from np –1–23∼29 of mature tRNA (Figure 1B and C). Therefore, both td-piRNAs belong to 5′-tRF with an identical 5′-terminal position to mature tRNAs and with variations at their 3′-terminal positions. Cyto tRNAGluUUC and/or tRNAGluCUC were also found to be a source (6.5%) for Siwi-bound td-piRNAs (Figure 1A), and td-piRGluUUC/CUC belongs to 5′-tRF as well (Supplementary Figure S5A and B). Although only 1% of the Siwi- or BmAgo3-bound piRNAs are annotated to Bombyx tRNAs (44), the enrichment of td-piRNAs for only specific species make those among the most abundant piRNAs; the most abundant td-piRNAs, td-piRAspGUC (np 1–28) in Siwi-bound piRNAs and td-piRHisGUG (np –1–25) in BmAgo3-bound piRNAs, rank among the top 20 of all identified individual piRNA species. Therefore, cyto tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG are very rich sources of piRNAs expressed in BmN4 cells.

In BmN4 cells, overall lengths of Siwi-bound piRNAs are longer than BmAgo3-bound piRNAs (44). This tendency is retained for both td-piRAspGUC and td-piRHisGUG (Figure 1D), suggesting that the two td-piRNAs are produced from a canonical piRNA biogenesis mechanism. To further address this point, we analyzed the two td-piRNAs in BmPapi-depleted BmN4 cells. BmPapi is a piRNA biogenesis factor that localizes at the outer membrane of mitochondria and supports PNLDC1-catalyzed 3′-end maturation of piRNAs (44,48). Due to its role in piRNA 3′-end maturation, BmPapi depletion globally causes a 3′-terminal extension of piRNA lengths (44). As shown in Figure 1D, the lengths of both td-piRAspGUC and td-piRHisGUG in BmPapi-depleted cells were longer than those in control cells, suggesting that the two td-piRNAs are bona-fide piRNAs produced via a canonical piRNA biogenesis mechanism, including the 3′-end maturation step catalyzed by PNLDC1 in support of BmPapi.

Because both td-piRAspGUC and td-piRHisGUG species share identical 5′-ends with mature tRNAs, these td-piRNAs are likely to originate from mature tRNAs resulting from the RNase P-mediated removal of 5′-leader sequences. However, mature tRNAs in the cytoplasm usually exist as aminoacylated forms that are tightly bound by an elongation factor for translation. Questions remained regarding how these tRNAs, forming rigid structures with interacting proteins, enter a piRNA biogenesis system where they are loaded onto Piwi proteins before PNLDC1-mediated processing, and why only specific tRNA species (i.e. tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG) are selected for piRNA production.

tRNA halves are produced from mature aminoacylated tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG in BmN4 cells

In BmN4 cells, our previous study revealed abundant accumulation of tRNA halves derived from cyto tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG (10). Both the 5′- and 3′-halves of the tRNAs manifested clear signals in northern blots, but we failed to detect signals for tRNA halves from other randomly chosen tRNAs (10). Because the specific expression of tRNA halves from cyto tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG was reminiscent of the specific expression of td-piRNAs from the two tRNAs, we next analyzed the expression profiles of tRNA halves.

In human hormone-dependent cancer cells, angiogenin (ANG), a member of the RNase A superfamily, cleaves the anticodon-loop of mature tRNAs to generate: (i) 5′-halves containing a 5′-terminal phosphate (5′-P) and a 3′-terminal 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (3′-cP) and (ii) 3′-halves containing a 5′-terminal hydroxyl group (5′-OH) and a 3′-terminal amino acid (3′-aa) (10). To analyze 3′-terminal structures of the 5′-halves derived from tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG (5′-halfAspGUC and 5′-halfHisGUG, respectively) expressed in BmN4 cells, total RNA was treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 PNK) or calf intestine phosphatase (CIP). T4 PNK removes both 3′-P and 3′-cP from RNAs, whereas CIP removes only a 3′-P and cannot remove a 3′-cP. Subsequently, efficiency of the ligations between the 5′-halves and a 3′-RNA adapter was examined by TaqMan qRT-PCR with a TaqMan probe that targets the boundary of the 5′-halves and the adapter. This was specifically for quantifying ligation products without cross-reaction from mature tRNAs or unligated tRNA halves. As shown in Figure 2A, the T4 PNK treatment, but not the CIP treatment, drastically increased the ligation efficiency of an RNA adapter to 5′-halves. No such increase was observed in control experiments for piRNAs which do not contain 3′-cP. These results suggest that 5′-halves contain a 3′-terminal cP, as shown in the 5′-halves expressed in human cancer cells.

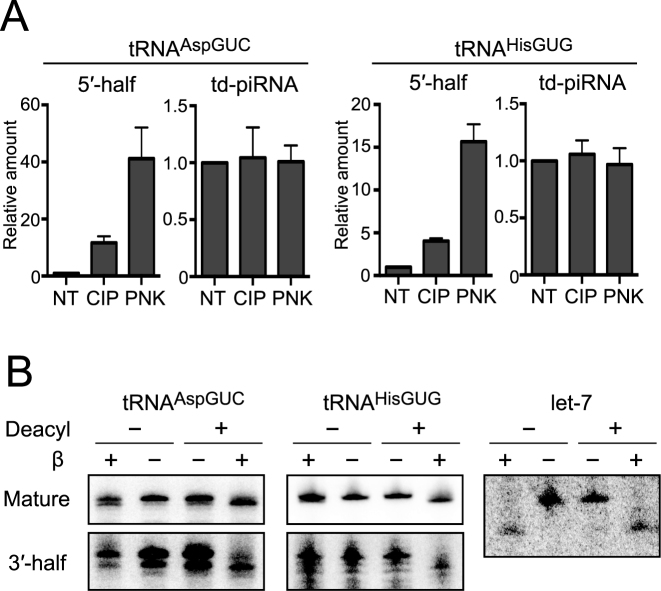

Figure 2.

Terminal structure analyses of tRNA halves expressed in BmN4 cells. (A) The 3′-terminal structures of 5′-tRNA halves and td-piRNAs derived from tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG were analyzed enzymatically. BmN4 total RNA was treated with CIP or T4 PNK (PNK). NT designates non-treated samples used as negative controls. The treated total RNA was subjected to 3′-adapter ligation by T4 Rnl, and the ligation efficiency was estimated by quantifying adapter-ligated target RNAs (5′-tRNA halves or piRNAs) using TaqMan qRT-PCR. Ligated products in NT samples were set as 1, and relative amounts are indicated. Averages of three independent experiments with SD values are shown. (B) To analyze the 3′-terminal structure of 3′-tRNA halves, BmN4 total RNA was subjected to deacylation treatment and sodium periodate oxidation, followed by β-elimination. The mature tRNAAspGUC, 3′-halfAspGUC, tRNAHisGUG, 3′-halfHisGUG, and let-7 miRNA (control) in the treated total RNA were analyzed by Northern blots.

To analyze the 3′-terminal structure of the 3′-half, BmN4 total RNA was subjected to deacylation treatment to remove amino acids from aminoacylated tRNAs. This was followed by sodium periodate oxidation and β-elimination, which reacts with the 3′-OH end to remove the 3′-terminal nucleotide (10). As shown in Figure 2B, β-eliminated 3′-halfAspGUC and 3′-halfHisGUG, as well as corresponding mature tRNAs, migrated faster than unreacted RNAs only after the RNAs were subjected to the deacylation treatment. In other words, without the deacylation treatment, β-elimination was unable to react with the 3′end of the 3′-halves and the mature tRNAs because of the presence of an amino acid. Control let-7 miRNA migrated faster after β-elimination, both with and without deacylation treatment, because let-7 does not have an amino acid. These results suggest that the 3′-halves are fully aminoacylated as shown in the 3′-halves expressed in human cancer cells (10), and therefore that the production of 5′- and 3′-halves occur via an anticodon-loop cleavage of mature aminoacylated tRNAs in BmN4 cells.

5′-tRNA halves in BmN4 cells are derived from only specific tRNA species including tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG

The 3′-terminal cP or amino acid of tRNA halves would inhibit the adapter ligation step included in standard RNA-seq methods, and therefore, the expression of tRNA halves cannot be captured by analyzing standard RNA-seq data. Instead, we utilized ‘cP-RNA-seq’ to identify expression profiles of 5′-halves expressed in BmN4 cells because it is able to selectively amplify and sequence RNAs containing a 3′-cP (10,49). Because selective amplification of cP-containing RNAs in this method is dependent on the periodate-mediated cleavage of other RNAs with a 3′-OH end, the 3′-terminal ribose 2′-O-methylation of piRNAs (54–57) was expected to make piRNAs amplifiable by cP-RNA-seq despite the absence of a 3′-cP (49). Indeed, as shown in Figure 3A, piRNAs were amplified by the procedures even without CIP and T4 PNK treatments as ∼145-bp cDNA bands (considering adapters’ lengths, inserted RNAs were estimated to be ∼27 nt). However, the full cP-RNA-seq procedures amplified ∼153-bp cDNA bands (inserted RNAs: ∼35 nt) that were much more abundant than piRNA bands in the same lane (Figure 3A). The dependency of the bands on T4 PNK treatment suggests that, as expected, the bands were derived from cP-containing 5′-tRNA halves.

Illumina sequencing of the ∼153-bp cDNA bands yielded ∼53 million reads after the quality check and adapter trimming, of which ∼31 million reads (∼59%) were actually mapped against Bombyx tRNA sequences. The tRNA-mapped reads were mostly 33 or 34 nt in length (Figure 3B), and derived from specific species of tRNAs. When we focused the tRNA-mapped reads to greater than 1 rpm with over 31-nt length that in aggregate accounted for 99.2% of the reads, only four cyto tRNA species (tRNAAspGUC, tRNALysCUU, tRNAHisGUG and tRNALysUUU) were identified to be a source of the reads with >1% of the tRNA-mapped reads, and another four cyto tRNA species (tRNAGluUUC, tRNAGlyGCC, tRNAGluCUC and tRNAGlnCUG) corresponded to the reads with 0.2−1% of the tRNA-mapped reads (Figure 3C). Reads derived from tRNAAspGUC were particularly enriched, comprising 85.1% of the total tRNA-mapped reads. Of the reads mapped to the four tRNAs, almost all sequences were unanimously derived from 5′-halves ranging from the 5′-end [np 1 (or np –1 for tRNAHisGUG)] to np 32–35 (Figure 3D). The abundant presence of 5′-halfAspGUC and 5′-halfHisGUG was consistent with the results from the Northern blots in our previous study (10). Further northern blots confirmed the accumulation of 5′-halfLysCUU and 5′-halfGluUUC/CUC, as identified by cP-RNA-seq, but not of unidentified 5′-halves derived from randomly-chosen tRNAs, tRNAGlyUUC, tRNASerCGA and tRNATyrGUA (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6), suggesting credibility of the cP-RNA-seq results. Although we failed to find a homolog of ANG in the Bombyx genome and the enzyme that cleaves tRNAs in BmN4 cells is unidentified, major cleavage sites within the anticodon-loop were located between cytidine and uridine or guanosine and uridine (Figure 3E). This is similar to the ANG-cleavage patterns for the production of tRNA halves in human cancer cells (10).

BmThg1l-mediated uridine addition at –1 np of tRNAHisGUG is required for the expression of td-piRHisGUG

Among all species of tRNAs, tRNAHisGUG is unique in that it contains an additional 5′-terminal nucleotide at np −1. Although the presence of guanosine at np −1 (G−1) has been widely known to be conserved across phyla (2), our recent study revealed the existence of other three −1 nucleotides (U−1 >> A−1, C−1) in tRNAHisGUG, in addition to G−1, and its 5′-half expressed in human BT-474 breast cancer cells (53). As observed in BT-474 cells, cP-RNA-seq data showed wide variations of 5′-terminal nucleotides from 5′-halfHisGUG in BmN4 cells. In addition to 5′-halfHisGUG lacking a −1 nucleotide (G1) or containing G−1, 5′-halfHisGUG containing U−1 and A−1 also were substantially expressed (16.6% and 10.7%, respectively) (Figure 4A). In contrast, the majority of both Siwi- and BmAgo3-bound td-piRHisGUG contained U−1 (Figure 4B), suggesting that tRNAHisGUG containing a 5′-terminal U−1 is selectively used to produce td-piRHisGUG. The observation is consistent with the major presence of a 5′-terminal uridine in piRNAs and the selective loading of 5′-U-containing RNAs on Piwi proteins as piRNA precursors in BmN4 cells (47).

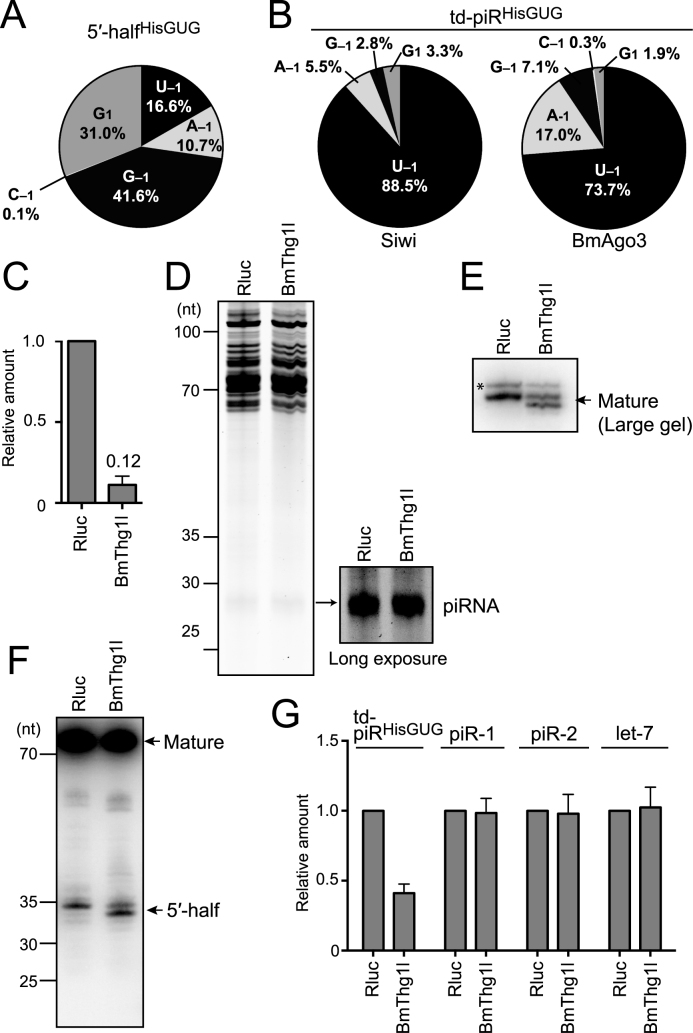

Figure 4.

Analyses of tRNAHisGUG and td-piRHisGUG in BmThg1l-depleted BmN4 cells. (A) Pie chart showing the 5′-terminal variations of BmN4 5′-halfHisGUG identified by cP-RNA-seq. (B) Pie charts showing the 5′-terminal variations of BmN4 td-piRHisGUG bound to Siwi and BmAgo3. (C) BmThg1l mRNA from BmN4 cells treated with dsRNAs targeting Renilla luciferase (Rluc, negative control) or BmThg1l was quantified by qRT-PCR. Each data set represents the average of three independent experiments with bars showing the SD. (D) Total RNA from Rluc- or BmThg1l-depleted cells was subjected to denaturing PAGE and stained by SYBR Gold. Long exposure enabled clear observation of the piRNA bands. (E, F) Total RNA from Rluc- or BmThg1l-depleted cells was subjected to Northern blot targeting the 5′-part of tRNAHisGUG using a large-size gel with 1 nt resolution for mature tRNA (E) or a standard-size gel for its 5′-half (F). Because the 5′-part of the tRNA is targeted, both mature tRNAHisGUG and 5′-halfHisGUG were detected. td-piRHisGUG was not detected due to a lack of sensitivity. For both mature tRNA and 5′-half, a band with slightly smaller size appeared upon BmThg1l-depletion, suggesting the role of BmThg1l in the –1 nucleotide addition to tRNAHisGUG. Bands shown with an asterisk might be non-specific as they seemed unaffected by the BmThg1l depletion. (G) The indicated piRNAs and let-7 miRNA in the Rluc- or BmThg1l-depleted cells were quantified by TaqMan qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S1) or qRT-PCR using a stem-loop primer. The amounts in Rluc-depleted cells were set as 1, and relative amounts are indicated. Averages of three independent experiments with SD values are shown.

As 5′-halfHisGUG originates from mature tRNAHisGUG, a U−1 nucleotide should be present in mature tRNAHisGUG. The Bombyx mori genome contains 14 tRNAHisGUG genes that encode identical mature tRNAHisGUG sequences. Because all 14 genes have adenosine at their −1 positions on the genome, the U−1 nucleotide should be added post-transcriptionally. tRNAHis guanylyltransferase (Thg1) has been shown to post-transcriptionally add G−1 to tRNAHisGUG (58). We retrieved sequences of the BmThg1l gene, a Bombyx homolog of the human THG1L, which is localized on Bm_scaf13 of chromosome 4 (Supplementary Figure S3). Because Thg1 or Thg1-like protein from Bacillus, archaea, and yeast can attach not only G−1, but also U−1, to the tRNA in vitro (59,60), we hypothesized that the BmThg1l protein is involved in the U−1 addition to tRNAHisGUG, which is required for the production of td-piRHisGUG. To examine this, we performed an RNAi knockdown of BmThg1l expression, which was effective for decreasing BmThg1l mRNA levels to ∼12% compared with the control knockdown (Figure 4C). The BmThg1l knockdown did not change the staining patterns of total RNA and the total piRNA fraction (Figure 4D). Strikingly, Northern blot using a large-size gel with a single nucleotide resolution revealed a lack of −1 nucleotides in mature tRNAHisGUG upon BmThg1l depletion (Figure 4E). Moreover, the BmThg1l knockdown caused a removal of the −1 nucleotide of 5′-halfHisGUG (Figure 4F). These results suggest that BmThg1l is the enzyme that adds the −1 nucleotide to mature tRNAHisGUG in BmN4 cells, and that the anticodon cleavage of the tRNA occurs after the −1 nucleotide addition, so that the −1 nucleotide property can be inherited by its 5′-half. TaqMan qRT-PCR quantification revealed the specific reduction of td-piRHisGUG upon BmThg11 depletion. All other examined piRNAs showed no quantitative changes (Figure 4G), which is consistent with the unchanged levels of total piRNAs shown in Figure 4D. The specific requirement of BmThg1l for td-piRHisGUG expression suggests that BmThg1l adds not only G−1 but also U−1 to tRNAHisGUG, which produces 5′-U−1-containing precursors for specific loading onto Piwi proteins to generate td-piRHisGUG. These results revealed the important function of BmThg11 in the formation of tRNAHisGUG −1 nucleotide and in the production of td-piRNA.

The expression of 5′-halves is linked to the expression of td-piRNAs

Both tRNA species identified as major sources for td-piRNAs, tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG (Figure 1), also have been identified as major sources for 5′-tRNA halves (Figure 3). tRNAGluUUC and/or tRNAGluCUC have also been detected as a source for both td-piRNAs and 5′-tRNA halves. This link has prompted us to hypothesize that 5′-halves, not mature tRNAs, could be direct intermediate precursors for the production of td-piRNAs. A high proportion of piRNAs contain a uridine at their 5′-end, and the presence of 5′-terminal uridine is a prerequisite for piRNA precursors to be loaded onto Piwi proteins in BmN4 cells (47). If mature tRNAs are direct substrates in piRNA biogenesis, the specific utilization of the limited tRNA species for piRNA production would need additional unknown mechanisms, because eight out of total 52 tRNA isoacceptors contain a 5′-terminal uridine. Alternatively, our hypothesis could explain the reason why tRNAAspGUC, tRNAHisGUG and tRNAGluUUC/CUC produce piRNAs in BmN4 cells, because the 5′-halfAspGUC, 5′-halfHisGUG, 5′-halfGluUUC and 5′-halfGluCUC are the only identified 5′-half species containing a 5′-terminal uridine (Figures 3C and 4A). Among the eight major 5′-half species expressed in BmN4 cells, the other four species contain a 5′-terminal guanosine that would prevent them from being loaded onto Piwi proteins and thereby make them inappropriate piRNA precursors.

To examine the involvement of 5′-halves in the biogenesis of td-piRNAs, we focused on NSun2, an RNA methyltransferase that methylates tRNAs to generate a 5-methylcytosine (m5C) modification (61,62). The NSun2-produced m5C modification protects the modified tRNAs from the anticodon cleavage and, therefore, prevents the generation of tRNA halves (14,63). In cells lacking NSun2 activity, the loss of the m5C modification made tRNAs more susceptible to anticodon cleavage and caused an accumulation of tRNA halves (14). These studies have designated NSun2 as a regulator factor for tRNA half expression. From the Bombyx genome, we retrieved sequences of the BmNSun2 gene, a Bombyx homolog of the human NSUN2, which is localized on Bm_scaf37 of chromosome 20 (Supplementary Figure S4). RNAi knockdown of BmNSun2, which was effective in decreasing BmNSun2 mRNA levels to ∼20% compared with the control reaction (Figure 5A), did not alter the expression patterns of total RNAs (Figure 5B) or control 5S rRNA (Figure 5C). In contrast, as expected, Northern blots showed the increased levels of both 5′-halfAspGUC and 5′-halfHisGUG upon BmNSun2 depletion, whereas the levels of corresponding mature tRNAs showed no alteration (Figure 5D). Strikingly, along with the increase in the 5′-halves, expression levels of td-piRAspGUC also increased upon BmNSun2 depletion (Figure 5D), although total piRNA abundance seemed not to have been altered (Figure 5B). Similarly, BmNSun2 depletion increased the levels of 5′-halfGluUUC and td-piR GluUUC/CUC (Supplementary Figure S5C).

Figure 5.

Analyses of 5′-tRNA halves and td-piRNAs in BmNSun2-depleted BmN4 cells. (A) BmNSun2 mRNA from BmN4 cells treated with dsRNAs targeting Rluc (negative control) or BmNSun2 was quantified by qRT-PCR. Each data set represents the average of three independent experiments with bars showing the SD. (B) Total RNA from Rluc- or BmNSun2-depleted cells was subjected to denaturing PAGE and stained by SYBR Gold. Long exposure enabled clear observation of the piRNA bands. (C) Total RNA from Rluc- or BmNSun2-depleted cells was subjected to northern blot targeting the Bombyx 5S rRNA. (D) Total RNA from Rluc- or BmNSun2-depleted cells was subjected to Northern blot targeting the 5′-part of mature tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG. Because the 5′-part of the tRNA was targeted, 5′-half and td-piRNA, as well as mature tRNA, were all detected. We failed to detect td-piRHisGUG due to a lack of sensitivity. The northern blot bands were quantified and shown as relative abundance in the right graph. Abundances in Rluc-depleted cells were set as 1, and the averages of three independent experiments with bars showing the SD are shown. (E) The 5′-halves and td-piRNAs in Rluc- or BmNSun2-depleted cells were quantified by TaqMan qRT-PCR. The amounts in Rluc-depleted cells were set as 1, and relative amounts are indicated. Averages of three independent experiments with SD values are shown.

Because our northern blot lacked the sensitivity to detect td-piRHisGUG as a clear band (Figure 5D), we established a more sensitive TaqMan qRT-PCR method (Supplementary Figure S1) that can selectively and specifically quantify 5′-halfAspGUC (np 1–34), td-piRAspGUC (np 1–28), 5′-halfHisGUG (np –1–34) and td-piRHisGUG (np –1–26). Total RNA was first subjected to sodium periodate oxidation to disrupt the 3′-OH ends of RNAs. For quantification of the piRNAs, subsequently, a 3′-adapter was ligated to the 3′-ends of the piRNAs, and quantification of the ligation products was then achieved by TaqMan qRT-PCR. For quantification of the 5′-halves, the periodate-treated RNA was further treated with T4 PNK to remove a 3′-cP, and then followed by a 3′-adapter ligation and TaqMan qRT-PCR quantification. These methods revealed that the expression levels of both 5′-halfAspGUC and 5′-halfHisGUG as well as their corresponding td-piRNAs, td-piRAspGUC and td-piRHisGUG, were all enhanced upon BmNSun2 knockdown (Figure 5E). Taken together, these data suggest that, in BmNSun2-deleted cells, an increase in the expression levels of 5′-halves enhanced the expression levels of corresponding td-piRNAs without quantitative change in mature tRNAs, indicating that the 5′-halves, not the mature tRNAs, are the direct precursors for td-piRNAs.

DISCUSSION

The number of reports characterizing the expression and function of tRNA-derived ncRNAs has been growing, which enforces the conceptual consensus that tRNAs are utilized to produce functional ncRNAs. A wide variety of specific tRFs are differentially expressed in different cells, tissues, and organisms; however, the molecular mechanisms governing the specific expression patterns of tRFs have not been clarified yet. Although the functional significance of tRFs has been increasingly apparent, the lack of information on their biogenesis mechanism limits our understanding of the necessity and inevitability of specific tRF expression profiles, as well as the reasons why cells utilize tRNAs for ncRNA production.

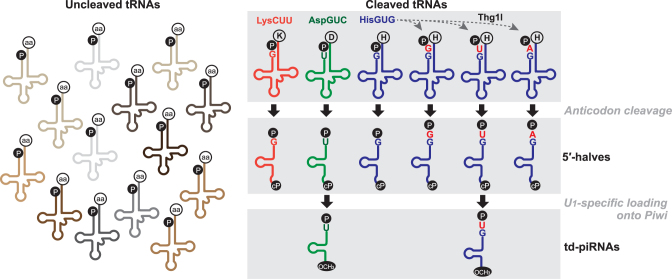

Here we report the biogenesis mechanism for td-piRNAs in Bombyx BmN4 cells, which could explain why only specific tRF species are expressed as piRNAs in the cells. In the current model for canonical piRNA biogenesis pathways, single-stranded RNAs are transcribed from defined genomic regions called piRNA clusters (37,64), and are likely fragmented into shorter precursor piRNAs by the involvement of Zucchini endonuclease and other unknown proteins (65–67). In BmN4 cells, precursor RNAs containing a 5′-terminal uridine are then selectively loaded onto Piwi proteins, followed by a PNLDC1-catalyzed 3′- to 5′-exonucleolytic trimming, that is supported by BmPapi, for the 3′-end formation of mature piRNAs (44,47,48). Our analyses on Siwi- and BmAgo3-bound piRNAs identified the 5′-tRFs derived from cyto tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG as major species of td-piRNAs (Figure 1). Our cP-RNA-seq identified tRNAAspGUC and tRNAHisGUG as major sources for 5′-tRNA halves as well (Figure 3). tRNAGluUUC and/or tRNAGluCUC were also detected as substrates for both td-piRNAs and 5′-tRNA halves. We assumed the common appearance of these tRNAs as substrate for both td-piRNAs and 5′-tRNA halves was not just a coincidence but fact suggesting a direct link between the expression of td-piRNAs and 5′-tRNA halves. Indeed, the increase of 5′-tRNA halves upon the knockdown of BmNSun2 clearly enhanced td-piRNA expression (Figure 5). These data, together with unchanged levels of mature tRNAs in BmNSun2-depleted cells, allow us to propose a biogenesis mechanism for td-piRNAs in which 5′-tRNA halves, rather than mature tRNAs, are the direct precursors for td-piRNAs (Figure 6). In our model, mature tRNAs are first cleaved at the anticodon-loop to produce tRNA halves. Among the generated 5′-tRNA halves, only those containing a 5′-terminal uridine are loaded onto Piwi proteins to be processed into td-piRNAs. Consequently, our model could provide an explanation for the expression of only a few specific td-piRNA species.

Figure 6.

A proposed model of the biogenesis of td-piRNAs in BmN4 cells.

The molecular mechanism underlying the anticodon-loop cleavage of only specific tRNA species in BmN4 cells remains unknown. In mammalian cells, ANG cleaves the anticodon-loops of mature tRNAs to produce tRNA halves, which is triggered by stresses and sex hormone signaling pathways (9,10,68). Although we could not find the Bombyx homolog of human ANG, the presence of a 3′-cP in 5′-tRNA halves (Figure 2) and major anticodon-loop cleavage sites between cytidine and uridine or guanosine and uridine (Figure 3) resembles the characteristics of ANG-generated 5′-tRNA halves in human cancer cells (10). Therefore, an endonuclease similar to ANG could be involved in the production of tRNA halves in BmN4 cells.

In contrast to previous reports describing the 5′-terminal G−1 as a major presence in tRNAHisGUG, the identified 5′-terminal variations of 5′-halfHisGUG revealed the substantial presence of the U−1 residue (Figure 4), which is consistent with our recent study on 5′-halfHisGUG in human cancer cells (53). The major presence of the U−1 residue in td-piRHisGUG (Figure 4) should be attributable to their selective loading onto Piwi proteins. The expression of td-piRHisGUG is clearly dependent on BmThg1l (Figure 4), suggesting that BmThg1l contributes to the activity of adding U−1, as well as G−1, to tRNAHisGUG, and that the BmThg1l protein is a significant regulator for the expression of tRFs derived from tRNAHisGUG.

Why are piRNAs not produced from mature tRNAs, but from tRNA halves? Since an amino acid was attached to the 3′-end of the 3′-tRNA half (Figure 2), tRNA halves should be produced by an anticodon-loop cleavage of mature aminoacylated tRNAs. Aminoacylated tRNAs are tightly bound by an elongation factor for translation. Therefore, their structure might be too rigid for piRNA biogenesis factors and/or Piwi proteins to access for piRNA production. The anticodon-loop could be among the most readily accessible regions for enzymes, which might be the reason that mature tRNAs are first cleaved at anticodon-loop, and then resultant tRNA halves, released from an elongation factor, become direct precursors for piRNAs. If this is the case, it might be possible that tRNA halves could also be direct precursors for many other tRFs, such as tRNA-derived miRNAs bound by Ago proteins. Because the expression of tRNA halves is variable in different cells and tissues, and is further regulated by tRNA modification states, various stressors, and hormones (9,10,14), the uniquely regulated biogenesis mechanism of tRNA halves may consequently provide the opportunity for cells to generate specific classes of tRNA-derived small regulatory RNAs whose species and abundance then also would be uniquely controlled. It will be intriguing to examine further the role of tRNA halves as direct precursors in the production of various shorter tRFs. Such attempts will advance our knowledge on the significance and functional meaning of differential expression profiles of tRNA-derived ncRNAs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr Megumi Shigematsu for helpful discussions.

Authors’ contributions: S.H. and Y.K. conceived the project and designed experiments. S.H., T.K. and K.M. performed experiments. S.H., P.L., K.M. and I.R. analyzed sequence data and all authors discussed the results. S.H. and Y.K. wrote the paper with input from other authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [GM106047 to Y.K.]; W.M. Keck Foundation grant (to I.R.); Institutional funds (to Y.K. and I.R.); JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad (to S.H.). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health [GM106047 to Y.K.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. RajBhandary U.L., Soll D.. Soll D, RajBhandary UL. tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. 1995; Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sprinzl M., Horn C., Brown M., Ioudovitch A., Steinberg S.. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998; 26:148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phizicky E.M., Hopper A.K.. tRNA biology charges to the front. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:1832–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sobala A., Hutvagner G.. Transfer RNA-derived fragments: origins, processing, and functions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011; 2:853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gebetsberger J., Polacek N.. Slicing tRNAs to boost functional ncRNA diversity. RNA Biol. 2013; 10:1798–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson P., Ivanov P.. tRNA fragments in human health and disease. FEBS Lett. 2014; 588:4297–4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shigematsu M., Kirino Y.. tRNA-derived short non-coding RNA as interacting partners of argonaute proteins. Gene Regul. Syst. Biol. 2015; 9:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar P., Kuscu C., Dutta A.. Biogenesis and function of transfer RNA-related fragments (tRFs). Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016; 41:679–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamasaki S., Ivanov P., Hu G.F., Anderson P.. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J. Cell Biol. 2009; 185:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Honda S., Loher P., Shigematsu M., Palazzo J.P., Suzuki R., Imoto I., Rigoutsos I., Kirino Y.. Sex hormone-dependent tRNA halves enhance cell proliferation in breast and prostate cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:E3816–E3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emara M.M., Ivanov P., Hickman T., Dawra N., Tisdale S., Kedersha N., Hu G.F., Anderson P.. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2010; 285:10959–10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ivanov P., Emara M.M., Villén J., Gygi S.P., Anderson P.. Angiogenin-Induced tRNA Fragments Inhibit Translation Initiation. Mol. Cell. 2011; 43:613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ivanov P., O’Day E., Emara M.M., Wagner G., Lieberman J., Anderson P.. G-quadruplex structures contribute to the neuroprotective effects of angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:18201–18206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blanco S., Dietmann S., Flores J.V., Hussain S., Kutter C., Humphreys P., Lukk M., Lombard P., Treps L., Popis M. et al. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J. 2014; 33:2020–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lyons S.M., Achorn C., Kedersha N.L., Anderson P.J., Ivanov P.. YB-1 regulates tiRNA-induced Stress Granule formation but not translational repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:6949–6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhahbi J.M., Spindler S.R., Atamna H., Yamakawa A., Boffelli D., Mote P., Martin D.I.. 5′ tRNA halves are present as abundant complexes in serum, concentrated in blood cells, and modulated by aging and calorie restriction. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Telonis A.G., Loher P., Honda S., Jing Y., Palazzo J., Kirino Y., Rigoutsos I.. Dissecting tRNA-derived fragment complexities using personalized transcriptomes reveals novel fragment classes and unexpected dependencies. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:24797–24822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cole C., Sobala A., Lu C., Thatcher S.R., Bowman A., Brown J.W., Green P.J., Barton G.J., Hutvagner G.. Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant Dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. RNA. 2009; 15:2147–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haussecker D., Huang Y., Lau A., Parameswaran P., Fire A.Z., Kay M.A.. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA. 2010; 16:673–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burroughs A.M., Ando Y., de Hoon M.J., Tomaru Y., Suzuki H., Hayashizaki Y., Daub C.O.. Deep-sequencing of human Argonaute-associated small RNAs provides insight into miRNA sorting and reveals Argonaute association with RNA fragments of diverse origin. RNA Biol. 2011; 8:158–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Z., Ender C., Meister G., Moore P.S., Chang Y., John B.. Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:6787–6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumar P., Anaya J., Mudunuri S.B., Dutta A.. Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. BMC Biol. 2014; 12:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Selitsky S.R., Baran-Gale J., Honda M., Yamane D., Masaki T., Fannin E.E., Guerra B., Shirasaki T., Shimakami T., Kaneko S. et al. Small tRNA-derived RNAs are increased and more abundant than microRNAs in chronic hepatitis B and C. Sci. Rep. 2015; 5:7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomson D.W., Pillman K.A., Anderson M.L., Lawrence D.M., Toubia J., Goodall G.J., Bracken C.P.. Assessing the gene regulatory properties of Argonaute-bound small RNAs of diverse genomic origin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:470–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yeung M.L., Bennasser Y., Watashi K., Le S.Y., Houzet L., Jeang K.T.. Pyrosequencing of small non-coding RNAs in HIV-1 infected cells: evidence for the processing of a viral-cellular double-stranded RNA hybrid. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:6575–6586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maute R.L., Schneider C., Sumazin P., Holmes A., Califano A., Basso K., Dalla-Favera R.. tRNA-derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down-regulated in B cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:1404–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanada T., Weitzer S., Mair B., Bernreuther C., Wainger B.J., Ichida J., Hanada R., Orthofer M., Cronin S.J., Komnenovic V. et al. CLP1 links tRNA metabolism to progressive motor-neuron loss. Nature. 2013; 495:474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawamura Y., Saito K., Kin T., Ono Y., Asai K., Sunohara T., Okada T.N., Siomi M.C., Siomi H.. Drosophila endogenous small RNAs bind to Argonaute 2 in somatic cells. Nature. 2008; 453:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karaiskos S., Naqvi A.S., Swanson K.E., Grigoriev A.. Age-driven modulation of tRNA-derived fragments in Drosophila and their potential targets. Biol. Direct. 2015; 10:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nie Z., Zhou F., Li D., Lv Z., Chen J., Liu Y., Shu J., Sheng Q., Yu W., Zhang W. et al. RIP-seq of BmAgo2-associated small RNAs reveal various types of small non-coding RNAs in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14:661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loss-Morais G., Waterhouse P.M., Margis R.. Description of plant tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs) associated with argonaute and identification of their putative targets. Biol. Direct. 2013; 8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Babiarz J.E., Ruby J.G., Wang Y., Bartel D.P., Blelloch R.. Mouse ES cells express endogenous shRNAs, siRNAs, and other Microprocessor-independent, Dicer-dependent small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:2773–2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siomi M.C., Sato K., Pezic D., Aravin A.A.. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011; 12:246–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vourekas A., Alexiou P., Vrettos N., Maragkakis M., Mourelatos Z.. Sequence-dependent but not sequence-specific piRNA adhesion traps mRNAs to the germ plasm. Nature. 2016; 531:390–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Keam S.P., Young P.E., McCorkindale A.L., Dang T.H., Clancy J.L., Humphreys D.T., Preiss T., Hutvagner G., Martin D.I., Cropley J.E. et al. The human Piwi protein Hiwi2 associates with tRNA-derived piRNAs in somatic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:8984–8995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hirano T., Iwasaki Y.W., Lin Z.Y., Imamura M., Seki N.M., Sasaki E., Saito K., Okano H., Siomi M.C., Siomi H.. Small RNA profiling and characterization of piRNA clusters in the adult testes of the common marmoset, a model primate. RNA. 2014; 20:1223–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brennecke J., Aravin A.A., Stark A., Dus M., Kellis M., Sachidanandam R., Hannon G.J.. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007; 128:1089–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Senti K.A., Jurczak D., Sachidanandam R., Brennecke J.. piRNA-guided slicing of transposon transcripts enforces their transcriptional silencing via specifying the nuclear piRNA repertoire. Genes Dev. 2015; 29:1747–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vrettos N., Maragkakis M., Alexiou P., Mourelatos Z.. Kc167, a widely used Drosophila cell line, contains an active primary piRNA pathway. RNA. 2017; 23:108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garcia-Silva M.R., Sanguinetti J., Cabrera-Cabrera F., Franzen O., Cayota A.. A particular set of small non-coding RNAs is bound to the distinctive Argonaute protein of Trypanosoma cruzi: insights from RNA-interference deficient organisms. Gene. 2014; 538:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Couvillion M.T., Bounova G., Purdom E., Speed T.P., Collins K.. A Tetrahymena Piwi bound to mature tRNA 3′ fragments activates the exonuclease Xrn2 for RNA processing in the nucleus. Mol. Cell. 2012; 48:509–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Couvillion M.T., Sachidanandam R., Collins K.. A growth-essential Tetrahymena Piwi protein carries tRNA fragment cargo. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:2742–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kawaoka S., Hayashi N., Suzuki Y., Abe H., Sugano S., Tomari Y., Shimada T., Katsuma S.. The Bombyx ovary-derived cell line endogenously expresses PIWI/PIWI-interacting RNA complexes. RNA. 2009; 15:1258–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Honda S., Kirino Y., Maragkakis M., Alexiou P., Ohtaki A., Murali R., Mourelatos Z.. Mitochondrial protein BmPAPI modulates the length of mature piRNAs. RNA. 2013; 19:1405–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiol J., Spinelli P., Laussmann M.A., Homolka D., Yang Z., Cora E., Coute Y., Conn S., Kadlec J., Sachidanandam R. et al. RNA clamping by Vasa assembles a piRNA amplifier complex on transposon transcripts. Cell. 2014; 157:1698–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nishida K.M., Iwasaki Y.W., Murota Y., Nagao A., Mannen T., Kato Y., Siomi H., Siomi M.C.. Respective functions of two distinct Siwi complexes assembled during PIWI-interacting RNA biogenesis in Bombyx germ cells. Cell Rep. 2015; 10:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kawaoka S., Izumi N., Katsuma S., Tomari Y.. 3′ end formation of PIWI-interacting RNAs in vitro. Mol. Cell. 2011; 43:1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Izumi N., Shoji K., Sakaguchi Y., Honda S., Kirino Y., Suzuki T., Katsuma S., Tomari Y.. Identification and functional analysis of the Pre-piRNA 3′ trimmer in silkworms. Cell. 2016; 164:962–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Honda S., Morichika K., Kirino Y.. Selective amplification and sequencing of cyclic phosphate-containing RNAs by the cP-RNA-seq method. Nat. Protoc. 2016; 11:476–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R.. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997; 25:955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. David M., Dzamba M., Lister D., Ilie L., Brudno M.. SHRiMP2: sensitive yet practical SHort Read Mapping. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:1011–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen C., Ridzon D.A., Broomer A.J., Zhou Z., Lee D.H., Nguyen J.T., Barbisin M., Xu N.L., Mahuvakar V.R., Andersen M.R. et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shigematsu M., Kirino Y.. 5′-Terminal nucleotide variations in human cytoplasmic tRNAHisGUG and its 5′-halves. RNA. 2017; 23:161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kirino Y., Mourelatos Z.. Mouse Piwi-interacting RNAs are 2′-O-methylated at their 3′ termini. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007; 14:347–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ohara T., Sakaguchi Y., Suzuki T., Ueda H., Miyauchi K.. The 3′ termini of mouse Piwi-interacting RNAs are 2′-O-methylated. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007; 14:349–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Saito K., Sakaguchi Y., Suzuki T., Siomi H., Siomi M.C.. Pimet, the Drosophila homolog of HEN1, mediates 2′-O-methylation of Piwi- interacting RNAs at their 3′ ends. Genes Dev. 2007; 21:1603–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Houwing S., Kamminga L.M., Berezikov E., Cronembold D., Girard A., van den Elst H., Filippov D.V., Blaser H., Raz E., Moens C.B. et al. A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell. 2007; 129:69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gu W., Jackman J.E., Lohan A.J., Gray M.W., Phizicky E.M.. tRNAHis maturation: an essential yeast protein catalyzes addition of a guanine nucleotide to the 5′ end of tRNAHis. Genes Dev. 2003; 17:2889–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rao B.S., Maris E.L., Jackman J.E.. tRNA 5′-end repair activities of tRNAHis guanylyltransferase (Thg1)-like proteins from Bacteria and Archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:1833–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jackman J.E., Phizicky E.M.. tRNAHis guanylyltransferase catalyzes a 3′-5′ polymerization reaction that is distinct from G-1 addition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:8640–8645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Motorin Y., Grosjean H.. Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA. 1999; 5:1105–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brzezicha B., Schmidt M., Makalowska I., Jarmolowski A., Pienkowska J., Szweykowska-Kulinska Z.. Identification of human tRNA:m5C methyltransferase catalysing intron-dependent m5C formation in the first position of the anticodon of the pre-tRNA Leu (CAA). Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:6034–6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tuorto F., Liebers R., Musch T., Schaefer M., Hofmann S., Kellner S., Frye M., Helm M., Stoecklin G., Lyko F.. RNA cytosine methylation by Dnmt2 and NSun2 promotes tRNA stability and protein synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012; 19:900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li X.Z., Roy C.K., Dong X., Bolcun-Filas E., Wang J., Han B.W., Xu J., Moore M.J., Schimenti J.C., Weng Z. et al. An ancient transcription factor initiates the burst of piRNA production during early meiosis in mouse testes. Mol. Cell. 2013; 50:67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nishimasu H., Ishizu H., Saito K., Fukuhara S., Kamatani M.K., Bonnefond L., Matsumoto N., Nishizawa T., Nakanaga K., Aoki J. et al. Structure and function of Zucchini endoribonuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012; 491:284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ipsaro J.J., Haase A.D., Knott S.R., Joshua-Tor L., Hannon G.J.. The structural biochemistry of Zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012; 491:279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pane A., Wehr K., Schupbach T.. zucchini and squash encode two putative nucleases required for rasiRNA production in the Drosophila germline. Dev. Cell. 2007; 12:851–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fu H., Feng J., Liu Q., Sun F., Tie Y., Zhu J., Xing R., Sun Z., Zheng X.. Stress induces tRNA cleavage by angiogenin in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 2009; 583:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.