Abstract

Fibroblasts in the tumor stroma are well recognized as having an indispensable role in carcinogenesis, including in the initiation of epithelial tumor formation. The association between cancer cells and fibroblasts has been highlighted in several previous studies. Regulation factors released from cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) into the tumor microenvironment have essential roles, including the support of tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis and therapy resistance. A mutual interaction between tumor-induced fibroblast activation, and fibroblast-induced tumor proliferation and metastasis occurs, thus CAFs act as tumor supporters. Previous studies have reported that by developing fibroblast-targeting drugs, it may be possible to interrupt the interaction between fibroblasts and the tumor, thus resulting in the suppression of tumor growth, and metastasis. The present review focused on the reciprocal feedback loop between fibroblasts and cancer cells, and evaluated the potential application of anti-CAF agents in the treatment of cancer.

Keywords: cancer associated fibroblasts, cancer, interaction, loop, therapy

1. Introduction

Tumors that comprise a mass of malignant epithelial cells are also surrounded by multiple non-cancerous cell populations, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, immune regulatory cells and cytokines in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (1). These stromal cells surrounding the tumor form a distinct microenvironment and were not considered to possess a role in cancer progression. However, it became evident that the molecular and biological abnormalities of cancer cells could not fully explain the complex changes involved in the regulation of tumor progression (2). Thus, an increasing number of studies have focused on the functions of the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression (3–5).

Activated fibroblasts, termed cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), are one of the major components of stromal cells. CAFs were first identified as negative factors in tumor development that had no effect on tumor cells; however, they have been identified as an essential component in tumor progression (6). With the reciprocal crosstalk between cancer cells and fibroblasts, CAFs undergo various morphological and biological transitions in response to tumor progression (7). Furthermore, CAFs have an important role in maintaining an optimal microenvironment for cancer cell survival and proliferation (6,7). Studies investigating the role of CAFs have reported that the therapeutic targeting of cancer cells alone is insufficient for the treatment of cancer (8). Thus, cancer therapy should co-target cancer cells and their microenvironment. CAFs are essential components to the tumor microenvironment and therefore represent a molecular target for the treatment of cancer (9).

The present study is a review of the recent developments in CAF research, and is aimed at gaining an improved understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying CAF involvement in tumor progression. Furthermore, the association between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment was analyzed in order to identify novel strategies for the treatment of cancer.

2. General characteristics of CAFs

CAFs are a heterogeneous population of cells with various origins, the majority of which are derived from resident fibroblasts. CAFs may also be derived from other cells, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), epithelial, pericytes, adipocytes and endothelial cells (10). CAFs in the tumor stroma can be differentiated according to their morphology and specific identifiable markers. CAFs are generally presented as large spindle-shaped cells similar to smooth muscle cells (myofilaments and electron dense patches) (11). α-smooth muscle actin is regarded as the most widely used biomarker for identifying CAFs (12). Fibroblast activation protein α (FAPα) is a cytomembrane protein that is selectively expressed by activated CAFs in various types of human epithelial cancer (13). Furthermore, podoplanin-a, S100A4, vimentin, fibroblast specific protein-1 (FSP-1), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors α and β are expressed in CAFs (14). Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), a novel biomarker for tumor fibroblasts in epithelial cancer, has also been detected in CAFs through genetic screenings and immunohistochemical studies. IGFBP7-expressing CAFs have been demonstrated to promote colon cancer cell proliferation through paracrine tumor-stroma interactions in vitro (15).

The application of microarray gene-expression analysis has enabled the comprehensive characterization of CAFs and has increased awareness on the importance of CAFs in oncological studies. A total of 46 differentially expressed genes regulated by the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway were identified in 15 paired CAF and normal fibroblast (NF) cell lines (16). All 46 genes were identified to encode for paracrine factors that are released into the tumor microenvironment. Of these results, 11 genes [intercellular-adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), THBS2, MME, OXTR, PDE3B, B3GALT2, EVI2B, COL14A1, GAL and MCTP2] were used to form a prognostic signature of CAFs in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (16). Similar studies have identified differentially-expressed genes between CAFs and NFs (17–20). Integrin α11 was identified to be primarily expressed in CAFs and possess prognostic significance for NSCLC (17). Furthermore, cyclooxygenase 2 and TGF-β2 expression in CAFs was confirmed through immunohistochemical analysis in metastatic colon cancer (18). In human primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma, smoothened homolog was identified to be overexpressed in CAFs compared with the expression in pancreatic NFs (19). In addition, numerous altered gene transcripts have been identified in breast CAFs, including that of ribsosomal protein S6 kinase α3, fibroblastic growth factor (FGF) receptor 1, nardilysin that enhances shedding of EGF (NRD1), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B, NFY and prostaglandin E synthase 2 (20). However, no significant differences in the gene expression pattern of NFs were reported with the most upregulated gene being chromobox 2, a polycomb homolog repressor of proto oncogenes (20).

3. Tumors induce fibroblast activation

When cancer cells metastasize to another organ, they recruit NFs to the tumor mass. The activated phenotype of fibroblasts in the tumor mass are induced by different genetic and epigenetic changes that are self-regulated, and regulated by cancer cells; however, the mechanisms underlying the transformation of NFs to CAFs remains unclear (21).

The activation of fibroblasts is induced by numerous cytokines secreted by cancer cells and other stroma cells, including TGF-β, epidermal growth factor (EGF), PDGF, FGF2 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 12 (22). Cell-cell communication through adhesion molecules, including ICAM1 and vascular-cell adhesion molecule 1 also enables fibroblast activation (23).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are an abundant type of endogenous small RNA molecule that downregulate target gene expression (24). A previous study demonstrated that miR-155 is upregulated, whereas miR-31 and miR-214 are downregulated in ovarian CAFs (25). C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 5 was identified as a target gene of miR-214. The results demonstrated that ovarian cancer cells induce the transformation of NFs to CAFs partially through regulation by miRNAs when NFs are co-cultured with cancer cells (25). These findings suggest that miRNAs have a regulatory role in the transformation of NFs to CAFs. Other miRNAs that have been identified to be differentially expressed in CAFs are listed in Table I (26–30).

Table I.

The regulation of miRNA in cancer associated fibroblasts.

| A, Upregulated miRNAs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | miRNA | Cancer type | Target gene | (Refs.) |

| Mitra et al, 2012 | miR-155 | Ovarian | (25) | |

| Zhao et al, 2012 | miR-266, miR-221-3p, miR-221-5p, miR-31-3p | Breast | ETS2 | (26) |

| Enkelmann et al, 2011 | miR-16, miR-320 | Bladder | (27) | |

| Aprelikova et al, 2014 | miR-29b, miR-146a miR-503 | Endometrial | (29) | |

| Wang et al, 2013 | miR-138, miR-210, miR-99a | Colorectal | (30) | |

| Bronisz et al, 2012 | miR-320 | Breast | (56) | |

| B, Downregulated miRNAs | ||||

| Mitra et al, 2012 | miR-31 | Ovarian | SATB2 | (25) |

| Mitra et al, 2012 | miR-214 | Ovarian | CCL5 | (25) |

| Zhao et al, 2012 | miR-205, miR-200c, miR-200b, miR-141, miR-101, miR-342-3p, Let-7g | Breast | ZEB1/SIP1 | (26) |

| Enkelmann et al, 2011 | miR-143, miR-145 | Bladder | (27) | |

| Yu et al, 2010 | miR-17/20 | Breast | IL-8, CXCL1, CK8, α-ENO | (28) |

| Aprelikova et al, 2014 | miR-31 | Endometrial | SATB2 | (29) |

| Wang et al, 2013 | miR-29b, miR-494, miR-126 | Colorectal | (30) | |

| Verghese et al, 2013 | miR-26b | Breast | TNKS1BP1, CPSF7, COL12A1 | (55) |

| Mongiat et al, 2010 | miR-15, miR-16 | Prostate | (57) | |

miR, microRNA; ETS2, ETS proto-oncogene 2 transcription factor; SATB2, SATB homeobox 2; CCL5, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1; SIP1, survival of motor neuron protein interacting protein 1; IL-8, interleukin-8; CXCL1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; CK8, keratin 8; α-ENO, enolase 1; TNKS1BP1, tankyrase 1 binding protein 1; CPSF7, cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 7; COL12A1, collagen type XII α 1 chain.

4. CAFs induce tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis and chemoresistance

CAFs induce tumor growth

Tumor growth depends on the abnormal and uncontrollable proliferation of cancer cells with simultaneous changes to the microenvironment. Among the stromal cells in the microenvironment surrounding the tumor, increasing evidence has reported that CAFs are targets and inducers of tumorigenic activation signals (31,32).

CAFs produce autocrine and/or paracrine cytokines that promote the biological characteristics of tumors. In addition to classical growth factors, including EGF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), novel CAF-secreted proteins [secreted frizzled related protein 1, and IGF like family member (IGF) 1 and 2], and membrane molecules (integrin α11 and syndecan-1) have also been identified to possess cancer cell-supporting roles (33). These factors directly or indirectly stimulate tumor growth and survival, or enhance their migratory and invasive properties.

Previous studies have demonstrated that chemokines secreted by CAFs into the microenvironment allow for the recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells (BMCs) and immune cells (34). CXCL12 (35), CXCL14 (36) and CCL5 (37) have been identified as pro-metastatic factors. In addition, MSC-derived CAFs are recruited to the stroma of the dysplastic stomach, and express interleukin (IL)-6, Wnt family member (Wnt) 5α and bone morphogenetic protein 4, all of which promote tumor growth through DNA hypomethylation (38). Furthermore, MSC-derived CAFs are recruited to the tumor through TGF-β and CXCL12 signaling (38). In oral squamous cell carcinoma (OCC), CCL2 expression in CAFs is upregulated, promoting the production of endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) in OC cells (OCCs) (37). Consequently, ROS induces the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins in OCCs, and promotes OCC proliferation, migration and invasion (39). Together, these chemokines and cytokines create a suitable microenvironment allowing for the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells.

CAFs stimulate tumor angiogenesis

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was originally identified as a multifunctional cytokine in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (40). The interaction between tumor and stromal cells can result in increased VEGF expression, with CAFs being the primary source of VEGF (41). Furthermore, CAF-derived PDGF has been demonstrated to be an essential factor in activating VEGF production. PDGF/PDGF receptor (R) signaling is an important regulatory pathway primarily involved in angiogenesis (41). PDGFs indirectly promote angiogenesis by recruiting stromal fibroblasts that secrete VEGF (42). Furthermore, PDGFs are able to recruit and induce BMCs to form endothelial or smooth muscle cells. Subsequently, PDGFs promote the proliferation and migration of endothelial, and smooth muscle cells (42). PDGF subunit B, which is produced by endothelial cells can induce the migration of pericytes to the vessel wall and maintain endothelial stability, thus leading to tumor angiogenesis (43).

Nagasaki et al (44) reported that cancer cells stimulate the secretion of IL-6 from fibroblasts, subsequently inducing tumor angiogenesis. IL-6R neutralization antibody inhibited IL-6 signaling and tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting the interaction between the cancer, and stroma. This finding suggests that IL-6 is a novel target for anti-angiogenesis therapy (44).

CAFs mediate tumor metastasis

Increasing evidence suggests a metastatic support role of CAFs in tumors (45,46), whereas data regarding the presence and role of CAFs in lymph node and distant metastasis is deficient. Stromal reactions in metastatic lymph nodes, possibly comprising metastasis-associated fibroblasts, have been described as reactive and fibrotic tissue with enhanced deposition of vitronectin and fibronectin, desmoplasia, nodal fibrosis and hyaline stroma (47). Immunohistochemical characterization of CAFs was reported in one of these studies, which assessed metastatic lymph node tissue from a patient with uterine cervix adenocarcinoma who received preoperative chemotherapy (47). Certain studies have suggested that the mesenchymal-like phenotype of CAFs is involved in enhancing the metastasis of cancer cells, whereas NFs with the epithelial-like phenotype inhibit the migration of breast cancer cells (48). Similarly, normal prostate epithelial cells induce intraepithelial neoplasia in vivo when co-injected with CAFs, but not when co-injected with NFs (49).

YAP is a transcription factor that may be a signature feature of CAFs. YAP has important roles in matrix stiffening, cancer cell invasion and angiogenesis, which are induced by CAFs (50). YAP regulates the expression of specific cytoskeletal proteins, including anillin actin binding protein, diaphanous related formin 3 and myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 (50). Additionally, CAFs secrete proinflammatory cytokines that stimulate the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, subsequently promoting tumorigenesis (51).

Notably, CAFs in the stroma of triple-negative breast cancer samples have been demonstrated to select for bone metastatic cells (52). CAFs produce CXCL12 and IGF1, which are prognostic markers for bone relapse and activators of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT serine/threonine kinase (AKT) signaling pathway (52). Cancer cells are primed for metastasis in the CXCL12-rich microenvironment of the bone marrow, thus suggesting an important role of CAFs in tumor metastasis. Another study demonstrated that a reduction in miR-148a expression in CAFs results in increased Wnt activity through the upregulation of its target gene WNT10B. Consequently, increased Wnt activity results in increased migration of endometrial cancer cells (53).

A study reported that the downregulation of miR-26b in CAFs stimulates the migration of fibroblasts, which is a dominant characteristic of the CAF phenotype. Furthermore, CAFs with reduced expression of miR-26b promote the migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells (54). Additionally, the PTEN/miR-320/ETS2 axis secretes proteins, such as Emilin2, that distinguish between normal and malignant stroma, and is associated with a higher rate of relapse in patients with breast cancer (55). This demonstrates that miR-320 is an essential regulator of the signaling pathway in fibroblasts involved in the regulation of the tumor microenvironment. Similar to in breast cancer, in prostate cancer, the downregulation of miR-15 and −16 in CAFs is mediated through activation of the AKT, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways, promoting prostate cancer migration, and angiogenesis (56).

CAFs induce resistance of cancer cells to therapy

Compared with cancer cells, CAFs are relatively genetically stable with a reduced probability of developing drug-resistance, thus representing as a potential therapeutic target with lower chances for the development of chemoresistance (57,58). However, an increasing amount of data has suggested that fibroblasts have a protective role that allows cancer cells to evade therapy, as described below.

PDGF

The interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) in the center of solid tumors is increased compared with that in the surrounding tumor tissue (59). Higher IFP reduces the efficiency of drug penetration into the tumor tissue, thus reducing the concentration of the drug reaching the tumor cells and increasing tumor cell viability (58). Strategies on improving chemotherapy have focused on reducing tumor IFP in order to increase the efficiency of drug transport and penetration into tumors (60).

PDGF and other associated tyrosine kinase receptors are expressed in various types of cancer. STI571, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), reduces tumor IFP and increases Taxol uptake in subcutaneously injected undifferentiated anaplastic thyroid carcinoma KAT-4 cell line-induced transplantable tumors in severe combined immune deficient mice (61,62).

HGF

HGF has been identified as an essential factor in of CAF-mediated resistance to B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) inhibitor therapy in melanoma with BRAFV600E mutation, as well as lapatinib resistance in HER2+ breast cancer (63,64).

TKIs exhibit strong inhibitory effects against NSCLC with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-activating mutations (65). However, the possibility of intrinsic or developing acquired resistance is an important consideration in the management of patients with cancer. The overexpression of HGF in CAF, a ligand of HGF receptor (MET), has been reported to contribute to resistance to EGFR-TKIs (66).

EGFR and HGF are coexpressed in colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines, and the activation of both receptors synergistically induces the proliferation of cancer cells (67). Cetuximab suppresses cell growth through dephosphorylation of EGFR, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and/or the AKT signaling pathway (68). It was demonstrated that CAF-derived HGF phosphorylates MET, but not EGFR or receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3 in cetuximab-treated cells. Subsequently, this was revealed to restore cell proliferation and rescue cells from G1 phase arrest, and apoptosis through restimulation of the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways (68). Notably, this effect is inhibited by suppressing MET activation with PHA-665752, a highly specific MET kinase inhibitor, or by knocking down MET expression using RNA interference (69).

Together, these data demonstrate that the presence of fibroblasts secreting HGF confers resistance to therapy. In addition, HGF can activate MET, which is expressed on cancer-initiating cells (CICs) in colon cancer, through paracrine signaling (70). This can sustain typical CIC properties, including long-term self-renewal, ultimately leading to resistance to anti-EGFR therapy (70).

Chemokines

Increasing evidence supports the presence of stromal cytokines that are important in the development of tumor chemoresistance.

CCL2 is an inflammatory chemokine, which is recruited by immune cells into the tumor microenvironment and has been demonstrated to confer resistance to paclitaxel, and docetaxel in prostate cancer (71). A previous study demonstrated that CCL2 expression is higher in three different paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines ES-2/TP, MES-OV/TP and OVCAR-3/TP compared with parental cells (72). Furthermore, treatment with a CCL2 inhibitor enhances the antitumor efficacy of paclitaxel and carboplatin combination therapy in ovarian cancer (72). CAFs can induce CCL2 production through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation, and in turn, CAF-derived CCL2 promotes cancer progression by regulating cancer stem cells through activation of the Notch signaling pathway (73).

The chemokine CXCL12 is the sole ligand of CXCR4. CAFs are an important source of CXCL12 in the tumor stroma. Previous studies have indicated that CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling contributes to chemoresistance by inducing the activation of focal adhesion kinase, ERK and AKT signaling pathways, enhancing the transcriptional activities of β-catenin, and NF-κB, and the expression of survival proteins (74,75). Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling pathway has been demonstrated to sensitize prostate cancer cells to docetaxel (76). Similar results have been observed in colon (77) and lung (78) cancer. Therefore, these studies suggest that chemokines, including CXCL12, may act as promising targets for cancer therapy, alone and/or in combination with other cytotoxic drugs.

Interleukin family

Emerging evidence suggests that the dynamic crosstalk between tumor cells and stromal fibroblasts underlie drug resistance. In CRC, IL-17A, which is overexpressed by CAFs in response to chemotherapy, bind to the IL-17A receptor expressed on CICs (79). Consequently, this results in the maintenance and development of therapeutic resistance of CICs through the upregulation of NF-κB (79). In ER-negative and triple-negative breast cancer, IL-17A protects from docetaxel-induced cell death through activation of ERK1, and 2, thus participating in therapy-resistance development (80).

IL-6, an inflammatory cytokine, is primarily secreted by CAFs. IL-6 promotes the growth and invasion of cancer cells through activation of STAT3 (81). NSCLC cells expressing persistently activated mutant EGFR are also associated with the IL-6 signaling pathway, which promotes the proliferation and survival of cells, leading to erlotinib resistance (82,83). IL-6 secreted by CAFs induces tamoxifen resistance through activation of the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in breast cancer cells (84). Inhibition of proteasome activity, IL-6 activity or the JAK/STAT3, or PI3K/AKT signaling pathways markedly reduced CAF-induced tamoxifen resistance (84). These results demonstrate that IL-6 creates a ‘protective niche’ that maintains the survival of residual tumor cells, consequently inducing tumor relapse.

Other factors

WNT16B is an important fibroblast-derived protein and treatment-induced factor that confers chemotherapy resistance. The chemotherapy resistance effects of fibroblast-derived WNT16B have been detected in vivo and in vitro, indicating that WNT16B reduces apoptosis induced by chemotherapy drugs in prostatic carcinoma (85). This study guides novel directions for combination therapies, including targeting fibroblast-derived WNT16B, which may reverse chemoresistance in breast and prostate cancer (85). Fibroblast-secreted high mobility group protein B1 is released into the tumor microenvironment and performs paracrine signaling on neighboring cancer cells, which has been suggested to induce chemoresistance in breast cancer (86).

5. Interaction loop

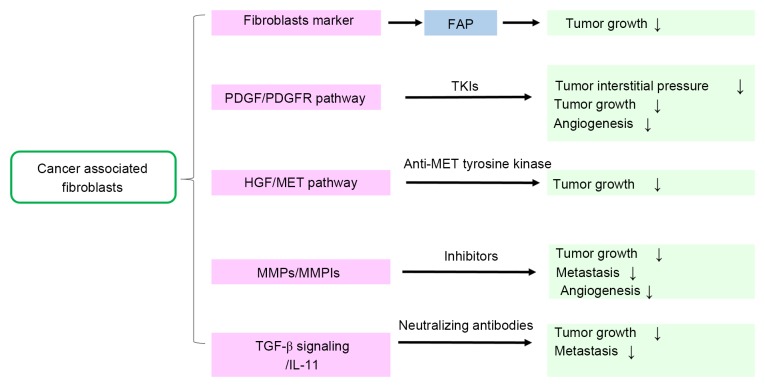

A bi-directional activation between cancer cells and fibroblasts has been identified as the leading cause of formation of the malignant phenotype of cancer. As aforementioned, the crosstalk between the two is important for tumor progression, and the interactions between them are induced by the reciprocal signaling of secreted components, including cytokines, and regulatory factors in the ECM. Cullen et al (87) reported that cancer cells produce PDGF, which induces fibroblast proliferation and the expression of IGF I, and II. Notably, IGFs secreted by fibroblasts in turn induce cancer cell proliferation and the synthesis of PDGF (87).

Cancer cells induce the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) by fibroblasts, which results in degradation of the extracellular matrix and enhances the invasiveness of cancer cells (88). In return, fibroblasts secrete growth factors, including HGF (89), keratinocyte growth factor (90), and IGF-1 and −2 (91), which stimulate the proliferation of cancer cells. Furthermore, a previous study reported that local cell-cell interactions between breast cancer cells and fibroblasts exhibit various effects on numerous genes, including the regulation of the expression of TGF-β-altered genes (92).

These signaling pathways are involved in positive feedback loops, which result in increased tumor cell numbers and/or amplification of signaling molecules, and consequently tumor therapy resistance. Thus, understanding the biological mechanism underlying CAFs may aid in the development of novel molecular-targeted therapies to inhibit these signaling feedback loops (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cancer-induced fibroblast activation and cytokine release followed by cancer associated fibroblast-induced tumor growth, and metastasis resulting in a feedback loop. TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; IGF, IGF like family member; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; ECM, extracellular matrix.

6. Inhibition of the feedback loop as an approach for anti-cancer therapy

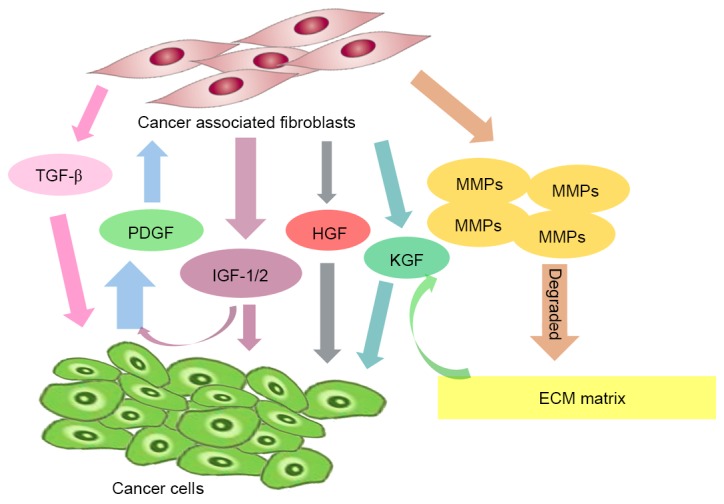

In order to target CAFs, a possible approach is to inhibit the feedback loop between fibroblasts and cancer cells. Such therapies have not yet been applied clinically, but based on the aforementioned evidence, the potential benefits of these treatments have been demonstrated. Inhibiting the feedback loop may involve the following approaches: Inhibition of fibroblasts directly and disruption of CAF-associated paracrine growth factor signals (Fig. 2) (6).

Figure 2.

Therapeutic target markers and pathways of CAFs. This fig presents the potential strategies of inhibiting the feedback loop and targeting CAFs during malignant cancer treatment. CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR, PDGF receptor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; MET, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; MMPIs, MMP inhibitors; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; IL-11, interleukin-11; FAP, fibroblast activation protein.

Targeting fibroblast markers directly

Therapy directed at specific fibroblast markers or the antigens presented on CAFs make CAFs particularly sensitive to cancer treatment. FAP is a membrane protein that is exclusively overexpressed on CAFs (93). FAP has been shown to support tumor growth and proliferation, making it a potential target for novel anticancer therapies (94). FAP-specific molecules selectively target fibroblasts and finally inhibit the growth of surrounding cancer cells (94,95).

FAPα-specific monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated therapeutic potential in cancer treatment. FAP5-DM1, a monoclonal maytansinoid-conjugated antibody, was demonstrated to inhibit and cause the complete regression of tumor growth in xenograft models of lung, pancreatic, and head and neck cancer in vivo (96).

Inhibition of FAPα enzyme activity using specific inhibitors has also been considered a promising approach to targeting fibroblasts. Using the peptidase inhibitor, PT-100 (talabostat) was revealed to reduce the tumor growth rate in numerous types of tumor animal models (97). Knocking down FAPα expression resulted in distinct tumor growth regression in an LSL-K-rasG12D genetic mouse model of lung cancer and in a colon cancer model, suggesting a tumor-supporting role of endogenous FAPα (98). Furthermore, treatment with PT-630 was able to inhibit tumor growth in the lung and colon cancer models (98).

Targeting paracrine signaling of fibroblasts

PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway

Cancers stimulate CAFs through the activation of PDGFR. A previous study demonstrated that following the overexpression of PDGF in cancer cells, there was an increase in the fibrotic stroma response, thus suggesting an essential role of PDGFR signaling in fibroblast activation (99).

Multiple TKIs, including imatinib, sorafenib and sunitinib, confer anti-PDGFR activity, and the association between TKIs and PDGFR activity is currently being investigated (100). Imatinib, is a breakpoint cluster region-ABL proto-oncogene 1 non-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which also exhibits anti-PDGFR and anti-c-kit kinase activity, resulting in decreased proliferation, and protein expression regulation in human colorectal fibroblasts (101). Furthermore, targeting PDGFRs increases the uptake and therefore the inhibitory effect of chemotherapeutics, including paclitaxel, by decreasing the IFP (62).

The indolinone derivative BIBF1120 is a potent inhibitor of VEGFR, PDGFR and FGFR family members. It has been revealed to inhibit MAPK and Akt signaling pathways in endothelial cells, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells, all of which contribute to angiogenesis, thus resulting in the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis. BIBF1120 has been applied clinically for the treatment of several types of tumor (102). Taken together, these findings suggest that the inhibition of PDGFR signaling may serve as a novel treatment approach for cancer.

HGF/MET signaling pathway

HGF is a growth factor that is primarily secreted by fibroblasts to activate c-Met on cancer cells (103). Genetic and biological studies have suggested that HGF and its receptor MET are potential targets for cancer treatment. The progress in understanding the structure and function of HGF/MET has led to the development of targeting drugs and numerous small molecule MET kinase inhibitors. Reports from previous clinical trails demonstrated that inhibiting MET signaling has great therapeutic value in several types of human cancers, including NSCLC (104,105).

The use of the anti-HGF monoclonal antibodies AMG-102 (rilotumumab) and AV-299 (ficlatuzumab) has been investigated in previous clinical trials (106,107). Furthermore, the anti-MET agents represent a novel strategy for the inhibition of the MET signaling pathway. Several phase I and II clinical trials have investigated the use of novel small molecules that target MET tyrosine kinase, including tivantinib (108), cabozantinib (109) and crizotinib (110–112). With the results of these translational and clinical studies, HGF/MET-targeted therapy is becoming a promising therapeutic choice for patients with NSCLC.

MMPs/MMP inhibitors (MMPIs)

MMPs are primarily derived from CAFs in various types of tumor. MMPs have been extensively detected in animal model experiments, which have demonstrated the importance of these proteases in inducing tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis (113,114). Inhibitors can be used to therapeutically target MMPs and lower the enzymatic activity, providing a prospective for future studies. Even though the majority of clinical trials on these drugs have reported insufficient results, research on MMPIs remains ongoing (115,116). Considering these explanations, one of the major difficulties in the future is the development of inhibitors or antibodies that bind to the active site of the enzyme and are highly specific to certain MMPs (117).

TGF-β signaling

TGF-β stimulates myofibroblast differentiation and the inhibition of TGF-β signaling in stromal fibroblasts result in significant regression in tumor growth; however, the antitumor effects of TGF-β signaling may depend primarily on individual tumor models (118). The TGF-β signaling pathway is increasingly considered as a therapeutic target due to its role in cancer cells and its capacity to instruct a protumorigenic program in tumor stromal cells (119). Several therapeutic agents that inhibit the TGF-β signaling pathway have been studied in preclinical and clinical trials. Neutralizing antibodies, soluble receptors and antisense oligonucleotides that target the ligand-receptor interaction, and inhibit the function of TGFBRI or TGFBRII have been studied in clinical experiments (120). The clinical application of the TGFBRI kinase inhibitor LY2157299 has been investigated in glioblastoma (121), hepatocellular carcinoma (122) and advanced pancreatic cancer (123); these studies have provided promising results.

Crosstalk between cancer cells and CAFs through TGF-β could suggest another therapeutic target. IL-11 has been recognized for its capacity to promote the maturation of platelets producing megakaryocyte progenitors in vitro and in the bone marrow in vivo (124). A previous study investigated the pro-metastatic effect of IL-11, which is secreted by TGF-β-stimulated CAFs in CRC (125). It was reported that IL-11 promotes the survival of tumor cells at the sites of metastatic colonization (125). This finding suggests that the clinical use of IL-11 to treat thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy agents should be reconsidered and the use of anti-IL11 therapies against CRC should be evaluated.

6. Conclusion

CAFs are considered as an essential component of tumorigenesis. Increasing evidence has suggested that CAFs exhibit a positive effect on the development of solid tumors. CAFs can modulate tumor microenvironment through diverse mechanisms, thus supporting tumor progression. Pre-clinical and clinical trials have revealed that CAFs are a potential target for the treatment of solid tumors.

References

- 1.Balkwill FR, Capasso M, Hagemann T. The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5591–5596. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spano D, Zollo M. Tumor microenvironment: A main actor in the metastasis process. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29:381–395. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swartz MA, Iida N, Roberts EW, Sangaletti S, Wong MH, Yull FE, Coussens LM, DeClerck YA. Tumor microenvironment complexity: Emerging roles in cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2473–2480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirri P, Chiarugi P. Cancer-associated-fibroblasts and tumour cells: A diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metast Rev. 2012;31:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh T, Pietras K, McAllister SS. Fibroblasts as architects of cancer pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y. Translational horizons in the tumor microenvironment: Harnessing breakthroughs and targeting cures. Med Res Rev. 2015;35:408–436. doi: 10.1002/med.21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slany A, Bileck A, Muqaku B, Gerner C. Targeting breast cancer-associated fibroblasts to improve anti-cancer therapy. Breast. 2015;24:532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderberg C, Pietras K. On the origin of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1461–1462. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Hu T, Shen J, Li SF, Lin JW, Zheng XH, Gao QH, Zhou HM. Separation, cultivation and biological characteristics of oral carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Oral Dis. 2006;12:375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugimoto H, Mundel TM, Kieran MW, Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JE, Lenter MC, Zimmermann RN, Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Fibroblast activation protein, a dual specificity serine protease expressed in reactive human tumor stromal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36505–36512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HM, Jung WH, Koo JS. Expression of cancer-associated fibroblast related proteins in metastatic breast cancer: An immunohistochemical analysis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:222. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0587-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rupp C, Scherzer M, Rudisch A, Unger C, Haslinger C, Schweifer N, Artaker M, Nivarthi H, Moriggl R, Hengstschläger M, et al. IGFBP7, a novel tumor stroma marker, with growth-promoting effects in colon cancer through a paracrine tumor-stroma interaction. Oncogene. 2015;34:815–825. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navab R, Strumpf D, Bandarchi B, Zhu CQ, Pintilie M, Ramnarine VR, Ibrahimov E, Radulovich N, Leung L, Barczyk M, et al. Prognostic gene-expression signature of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts in non-small cell lung cancer; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2011; pp. 7160–7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu CQ, Popova SN, Brown ER, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Navab R, Shih W, Li M, Lu M, Jurisica I, Penn LZ, et al. Integrin alpha11 regulates IGF2 expression in fibroblasts to enhance tumorigenicity of human non-small-cell lung cancer cells; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2007; pp. 11754–11759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa H, Liyanarachchi S, Davuluri RV, Auer H, Martin EW, Jr, de la Chapelle A, Frankel WL. Role of cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts in metastatic colon cancer to the liver and their expression profiles. Oncogene. 2004;23:7366–7377. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter K, Omura N, Hong SM, Griffith M, Vincent A, Borges M, Goggins M. Overexpression of smoothened activates the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1781–1789. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozenchan PB, Carraro DM, Brentani H, de Carvalho Mota LD, Bastos EP, e Ferreira EN, Torres CH, Katayama ML, Roela RA, Lyra EC, et al. Reciprocal changes in gene expression profiles of cocultured breast epithelial cells and primary fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2767–2777. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Räsänen K, Vaheri A. Activation of fibroblasts in cancer stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2713–2722. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayton A, Evans RA, Pettit E, Hallett M, Williams JD, Steadman R. Cellular activation through the ligation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:443–453. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitra AK, Zillhardt M, Hua Y, Tiwari P, Murmann AE, Peter ME, Lengyel E. MicroRNAs reprogram normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts in ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1100–1108. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao L, Sun Y, Hou Y, Peng Q, Wang L, Luo H, Tang X, Zeng Z, Liu M. MiRNA expression analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and normal fibroblasts in breast cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2051–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enkelmann A, Heinzelmann J, von Eggeling F, Walter M, Berndt A, Wunderlich H, Junker K. Specific protein and miRNA patterns characterise tumour-associated fibroblasts in bladder cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:751–759. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Z, Willmarth NE, Zhou J, Katiyar S, Wang M, Liu Y, McCue PA, Quong AA, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. microRNA 17/20 inhibits cellular invasion and tumor metastasis in breast cancer by heterotypic signaling; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2010; pp. 8231–8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aprelikova O, Yu X, Palla J, Wei BR, John S, Yi M, Stephens R, Simpson RM, Risinger JI, Jazaeri A, Niederhuber J. The role of miR-31 and its target gene SATB2 in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2014;9:4387–4398. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Wang Z, Xu K, Ruan Z, Chen L. miRNA expression analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and normal fibroblasts in colorectal cancer. J Mod Oncol. 2013;09:1918–1922. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhowmick NA, Neilson E G, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonda TA, Varro A, Wang TC, Tycko B. Molecular biology of cancer-associated fibroblasts: Can these cells be targeted in anti-cancer therapy?; Seminars Cell Dev Biol; 2009; pp. 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostman A, Augsten M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor growth-bystanders turning into key players. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Servais C, Erez N. From sentinel cells to inflammatory culprits: Cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumour-related inflammation. J Pathol. 2013;229:198–207. doi: 10.1002/path.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luker KE, Lewin SA, Mihalko LA, Schmidt BT, Winkler JS, Coggins NL, Thomas DG, Luker GD. Scavenging of CXCL12 by CXCR7 promotes tumor growth and metastasis of CXCR4-positive breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:4750–4758. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Augsten M, Sjöberg E, Frings O, Vorrink SU, Frijhoff J, Olsson E, Borg Å, Östman A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts expressing CXCL14 rely upon NOS1-derived nitric oxide signaling for their tumor-supporting properties. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2999–3010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mi Z, Bhattacharya SD, Kim VM, Guo H, Talbot LJ, Kuo PC. Osteopontin promotes CCL5-mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated breast cancer metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:477–487. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, Baik GH, Shibata W, Diprete B, Betz KS, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Xu Q, Wu Y, Li J, Tang D, Han L, Fan Q. A CCL2/ROS autoregulation loop is critical for cancer-associated fibroblasts-enhanced tumor growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1362–1370. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibuya M, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by VEGF receptors in regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomes FG, Nedel F, Alves AM, Nör JE, Tarquinio SB. Tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis: Tumor/endothelial crosstalk and cellular/microenvironmental signaling mechanisms. Life Sci. 2013;92:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrara N. Pathways mediating VEGF-independent tumor angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Liu J. Tumor stroma as targets for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:200–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagasaki T, Hara M, Nakanishi H, Takahashi H, Sato M, Takeyama H. Interleukin-6 released by colon cancer-associated fibroblasts is critical for tumour angiogenesis: Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppressed angiogenesis and inhibited tumour-stroma interaction. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:469–478. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karagiannis GS, Poutahidis T, Erdman SE, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Diamandis EP. Cancer-associated fibroblasts drive the progression of metastasis through both paracrine and mechanical pressure on cancer tissue. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1403–1418. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vpavlides S, Vera I, Gandara R, Sneddon S, Pestell RG, Mercier I, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Warburg meets autophagy: Cancer-associated fibroblasts accelerate tumor growth and metastasis via oxidative stress, mitophagy, and aerobic glycolysis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1264–1284. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Wever O, Van Bockstal M, Mareel M, Hendrix A, Bracke M. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts provide operational flexibility in metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;25:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumont N, Liu B, DeFilippis RA, Chang H, Rabban JT, Karnezis AN, Tjoe JA, Marx J, Parvin B, Tlsty TD. Breast fibroblasts modulate early dissemination, tumorigenesis, and metastasis through alteration of extracellular matrix characteristics. Neoplasia. 2013;15:249–262. doi: 10.1593/neo.121950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calvo F, Ege N, Grande-Garcia A, Hooper S, Jenkins RP, Chaudhry SI, Harrington K, Williamson P, Moeendarbary E, Charras G, Sahai E. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, Arron ST, Hanahan D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are activated in incipient neoplasia to orchestrate tumor-promoting inflammation in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cancer cell. 2010;17:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang XH, Jin X, Malladi S, Zou Y, Wen YH, Brogi E, Smid M, Foekens JA, Massagué J. Selection of bone metastasis seeds by mesenchymal signals in the primary tumor stroma. Cell. 2013;154:1060–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aprelikova O, Palla J, Hibler B, Yu X, Greer YE, Yi M, Stephens R, Maxwell GL, Jazaeri A, Risinger JI, et al. Silencing of miR-148a in cancer-associated fibroblasts results in WNT10B-mediated stimulation of tumor cell motility. Oncogene. 2013;32:3246–3253. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verghese ET, Drury R, Green CA, Holliday DL, Lu X, Nash C, Speirs V, Thorne JL, Thygesen HH, Zougman A, et al. MiR-26b is down-regulated in carcinoma-associated fibroblasts from ER-positive breast cancers leading to enhanced cell migration and invasion. J Pathol. 2013;231:388–399. doi: 10.1002/path.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bronisz A, Godlewski J, Wallace JA, Merchant AS, Nowicki MO, Mathsyaraja H, Srinivasan R, Trimboli AJ, Martin CK, Li F, et al. Reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment by stromal PTEN-regulated miR-320. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ncb2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mongiat M, Marastoni S, Ligresti G, Lorenzon E, Schiappacassi M, Perris R, Frustaci S, Colombatti A. The extracellular matrix glycoprotein elastin microfibril interface located protein 2: A dual role in the tumor microenvironment. Neoplasia. 2010;12:294–304. doi: 10.1593/neo.91930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Correia AL, Bissell MJ. The tumor microenvironment is a dominant force in multidrug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kerbel RS. A cancer therapy resistant to resistance. Nature. 1997;390:335–336. doi: 10.1038/36978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swartz MA, Lund AW. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: Linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nrc3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khawar IA, Kim JH, Kuh HJ. Improving drug delivery to solid tumors: Priming the tumor microenvironment. J Control Release. 2015;201:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pietras K, Östman A, Sjöquist M, Buchdunger E, Reed RK, Heldin CH, Rubin K. Inhibition of Platelet-derived growth factor receptors reduces interstitial hypertension and increases transcapillary transport in tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2929–2934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pietras K, Rubin K, Sjöblom T, Buchdunger E, Sjöquist M, Heldin CH, Ostman A. Inhibition of PDGF receptor signaling in tumor stroma enhances antitumor effect of chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5476–5484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, Penuel E, Burton L, Chan E, Peng J, Lin E, Wang Y, Sosman J, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yano S, Wang W, Li Q, Yamada T, Takeuchi S, Matsumoto K, Nishioka Y, Sone S. HGF-MET in resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Curr Signal Trans Ther. 2011;6:228–233. doi: 10.2174/157436211795659928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liska D, Chen CT, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Christensen JG, Weiser MR. HGF rescues colorectal cancer cells from EGFR inhibition via MET activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:472–482. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamatodani T, Ekblad L, Kjellén E, Johnsson A, Mineta H, Wennerberg J. Epidermal growth factor receptor status and persistent activation of Akt and p44/42 MAPK pathways correlate with the effect of cetuximab in head and neck and colon cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:395402. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liska D, Chen CT, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Christensen JG, Weiser MR. HGF rescues colorectal cancer cells from EGFR inhibition via MET activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:472–482. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luraghi P, Reato G, Cipriano E, Sassi F, Orzan F, Bigatto V, De Bacco F, Menietti E, Han M, Rideout WM, III, et al. MET signaling in colon cancer stem-like cells blunts the therapeutic response to EGFR inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1857–1869. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2340-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qian DZ, Rademacher BL, Pittsenbarger J, Huang CY, Myrthue A, Higano CS, Garzotto M, Nelson PS, Beer TM. CCL2 is induced by chemotherapy and protects prostate cancer cells from docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity. Prostate. 2010;70:433–442. doi: 10.1002/pros.21077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moisan F, Francisco EB, Brozovic A, Duran GE, Wang YC, Chaturvedi S, Seetharam S, Snyder LA, Doshi P, Sikic BI. Enhancement of paclitaxel and carboplatin therapies by CCL2 blockade in ovarian cancers. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsuyada A, Chow A, Wu J, Somlo G, Chu P, Loera S, Luu T, Li AX, Wu X, Ye W, et al. CCL2 mediates cross-talk between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2768–2779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weekes CD, Song D, Arcaroli J, Wilson LA, Rubio-Viqueira B, Cusatis G, Garrett-Mayer E, Messersmith WA, Winn RA, Hidalgo M. Stromal cell-derived factor 1α mediates resistance to mTOR-directed therapy in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia. 2012;14:690–701. doi: 10.1593/neo.111810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh S, Srivastava SK, Bhardwaj A, Owen LB, Singh AP. CXCL12-CXCR4 signalling axis confers gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer cells: A novel target for therapy. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Domanska UM, Timmer-Bosscha H, Nagengast WB, Munnink TH Oude, Kruizinga RC, Ananias HJ, Kliphuis NM, Huls G, De Vries EG, de Jong IJ, Walenkamp AM. CXCR4 inhibition with AMD3100 sensitizes prostate cancer to docetaxel chemotherapy. Neoplasia. 2012;14:709–718. doi: 10.1593/neo.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heckmann D, Maier P, Laufs S, Wenz F, Zeller WJ, Fruehauf S, Allgayer H. CXCR4 expression and treatment with SDF-1α or plerixafor modulate proliferation and chemosensitivity of colon cancer cells. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:124–132. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burger JA, Stewart DJ, Wald O, Peled A. Potential of CXCR4 antagonists for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:621–630. doi: 10.1586/era.11.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lotti F, Jarrar AM, Pai RK, Hitomi M, Lathia J, Mace A, Gantt GA, Jr, Sukhdeo K, DeVecchio J, Vasanji A, et al. Chemotherapy activates cancer-associated fibroblasts to maintain colorectal cancer-initiating cells by IL-17A. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2851–2872. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cochaud S, Giustiniani J, Thomas C, Laprevotte E, Garbar C, Savoye AM, Curé H, Mascaux C, Alberici G, Bonnefoy N, et al. IL-17A is produced by breast cancer TILs and promotes chemoresistance and proliferation through ERK1/2. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3456. doi: 10.1038/srep03456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Studebaker AW, Storci G, Werbeck JL, Sansone P, Sasser AK, Tavolari S, Huang T, Chan MW, Marini FC, Rosol TJ, et al. Fibroblasts isolated from common sites of breast cancer metastasis enhance cancer cell growth rates and invasiveness in an interleukin-6-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9087–9095. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gao SP, Mark KG, Leslie K, Pao W, Motoi N, Gerald WL, Travis WD, Bornmann W, Veach D, Clarkson B, Bromberg JF. Mutations in the EGFR kinase domain mediate STAT3 activation via IL-6 production in human lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3846–3856. doi: 10.1172/JCI31871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yao Z, Fenoglio S, Gao DC, Camiolo M, Stiles B, Lindsted T, Schlederer M, Johns C, Altorki N, Mittal V, et al. TGF-beta IL-6 axis mediates selective and adaptive mechanisms of resistance to molecular targeted therapy in lung cancer; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2010; pp. 15535–15540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun X, Mao Y, Wang J, Zu L, Hao M, Cheng G, Qu Q, Cui D, Keller ET, Chen X, et al. IL-6 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts induces tamoxifen resistance in luminal breast cancer. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.158. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun Y, Campisi J, Higano C, Beer TM, Porter P, Coleman I, True L, Nelson PS. Treatment-induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nat Med. 2012;18:1359–1368. doi: 10.1038/nm.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amornsupuk K, Insawang T, Thuwajit P, O-Charoenrat P, Eccles SA, Thuwajit C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce high mobility group box 1 and contribute to resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:955. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cullen KJ, Smith HS, Hill S, Rosen N, Lippman ME. Growth factor messenger RNA expression by human breast fibroblasts from benign and malignant lesions. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4978–4985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shay G, Lynch CC, Fingleton B. Moving targets: Emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis. Matrix Biol 44–46. 2015:1–206. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jia CC, Wang TT, Liu W, Fu BS, Hua X, Wang GY, Li TJ, Li X, Wu XY, Tai Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts from hepatocellular carcinoma promote malignant cell proliferation by HGF secretion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin J, Liu C, Ge L, Gao Q, He X, Liu Y, Li S, Zhou M, Chen Q, Zhou H. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promotes the proliferation of a lingual carcinoma cell line by secreting keratinocyte growth factor. Tumor Biol. 2011;32:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weroha SJ, Haluska P. The insulin-like growth factor system in cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41:335–350.vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hawinkels LJ, Paauwe M, Verspaget HW, Wiercinska E, van der Zon JM, van der Ploeg K, Koelink PJ, Lindeman JH, Mesker W, ten Dijke P, Sier CF. Interaction with colon cancer cells hyperactivates TGF-β signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2014;33:97–107. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes-bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu R, Li H, Liu L, Yu J, Ren X. Fibroblast activation protein: A potential therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:123–129. doi: 10.4161/cbt.13.3.18696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.LeBeau AM, Brennen WN, Aggarwal S, Denmeade SR. Targeting the cancer stroma with a fibroblast activation protein-activated promelittin protoxin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1378–1386. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ostermann E, Garin-Chesa P, Heider KH, Kalat M, Lamche H, Puri C, Kerjaschki D, Rettig WJ, Adolf GR. Effective immunoconjugate therapy in cancer models targeting a serine protease of tumor fibroblasts. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4584–4592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Adams S, Miller GT, Jesson MI, Watanabe T, Jones B, Wallner BP. PT-100, a small molecule dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitor, has potent antitumor effects and augments antibody-mediated cytotoxicity via a novel immune mechanism. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5471–5480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Santos AM, Jung J, Aziz N, Kissil JL, Puré E. Targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor stromagenesis and growth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3613–3625. doi: 10.1172/JCI38988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heldin CH. Targeting the PDGF signaling pathway in tumor treatment. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Steeghs N, Nortier JW, Gelderblom H. Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of solid tumors: An update of recent developments. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:942–953. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pietras K, Pahler J, Bergers G, Hanahan D. Functions of paracrine PDGF signaling in the proangiogenic tumor stroma revealed by pharmacological targeting. PLos Med. 2008;5:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hilberg F, Roth GJ, Krssak M, Kautschitsch S, Sommergruber W, Tontsch-Grunt U, Garin-Chesa P, Bader G, Zoephel A, Quant J, et al. BIBF 1120: Triple angiokinase inhibitor with sustained receptor blockade and good antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4774–4782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cecchi F, Rabe DC, Bottaro DP. Targeting the HGF/Met signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:553–572. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.680957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C, Woude G Vande. Targeting MET in cancer: Rationale and progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:89–103. doi: 10.1038/nrc3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sadiq AA, Salgia R. MET as a possible target for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1089–1096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.9422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Oliner KS, Tang R, Anderson A, et al. J Clin Oncol Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2318 Mill Road, Ste 800, Alexandria, Va 22314 USA: 2012. Evaluation of MET pathway biomarkers in a phase II study of rilotumumab (R, AMG 102) or placebo (P) in combination with epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine (ECX) in patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic gastric (G) or esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tan E, Park K, Lim WT, et al. Phase 1b study of ficlatuzumab (AV-299), an anti-hepatocyte growth factor monoclonal antibody, in combination with gefitinib in Asian patients with NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl):493S. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Katayama R, Aoyama A, Yamori T, Qi J, Oh-hara T, Song Y, Engelman JA, Fujita N. Cytotoxic activity of tivantinib (ARQ 197) is not due solely to c-MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3087–3096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wakelee H, Gettinger S, Engelman J, et al. A phase Ib/II study of XL184 (BMS 907351) with and without erlotinib (E) in patients (pts) with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings; 2010.p. 3017.

- 110.Tanizaki J, Okamoto I, Okamoto K, Takezawa K, Kuwata K, Yamaguchi H, Nakagawa K. MET tyrosine kinase inhibitor crizotinib (PF-02341066) shows differential antitumor effects in non-small cell lung cancer according to MET alterations. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1624–1631. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822591e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Feng Y, Thiagarajan PS, Ma PC. MET signaling: Novel targeted inhibition and its clinical development in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:459–467. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182417e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Blumenschein GR, Jr, Mills GB, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Targeting the hepatocyte growth factor-cMET axis in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3287–3296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:267–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pavlaki M, Zucker S. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (MMPIs): The beginning of phase I or the termination of phase III clinical trials. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:177–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1023047431869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shepherd FA, Giaccone G, Seymour L, Debruyne C, Bezjak A, Hirsh V, Smylie M, Rubin S, Martins H, Lamont A, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of marimastat after response to first-line chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer: A trial of the national cancer institute of Canada-clinical trials group and the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4434–4439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Konstantinopoulos PA, Karamouzis MV, Papatsoris AG, Papavassiliou AG. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1156–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bierie B, Moses HL. TGF-β and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lonning S, Mannick J, McPherson J. Antibody targeting of TGF-β in cancer patients. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:2176–2189. doi: 10.2174/138920111798808392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hawinkels LJ, Ten Dijke P. Exploring anti-TGF-β therapies in cancer and fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29:140–152. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rodon J, Carducci MA, Sepulveda-Sánchez JM, Azaro A, Calvo E, Seoane J, Braña I, Sicart E, Gueorguieva I, Cleverly AL, et al. First-in-human dose study of the novel transforming growth factor-β receptor I kinase inhibitor LY2157299 monohydrate in patients with advanced cancer and glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:553–560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rani B, Dituri F, Cao Y, Engström U, Lupo L, Dooley S, Moustakas A, Giannelli G. P0320: Targeting TGF-beta I with the transforming growth factor receptor type I kinase inhibitor, LY2157299, modulates stemness-related biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S429. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(15)30535-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Whatcott CJ, Dumas SN, Watanabe A, LoBello J, Von Hoff DD, Han H. Abstract 2135: TGFβRI inhibition results in reduced collagen expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. DOI: 10.1158/1538-7445. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Johnstone CN, Chand A, Putoczki TL, Ernst M. Emerging roles for IL-11 signaling in cancer development and progression: Focus on breast cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Calon A, Espinet E, Palomo-Ponce S, Tauriello DV, Iglesias M, Céspedes MV, Sevillano M, Nadal C, Jung P, Zhang XH, et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]