Abstract

The aim of this review is to advocate for more integrated and universally accessible health systems, built on a foundation of primary health care and public health. The perspective outlined identified health systems as the frame of reference, clarified terminology and examined complementary perspectives on health. It explored the prospects for universal and integrated health systems from a global perspective, the role of healthy public policy in achieving population health and the value of the social-ecological model in guiding how best to align the components of an integrated health service. The importance of an ethical private sector in partnership with the public sector is recognized. Most health systems around the world, still heavily focused on illness, are doing relatively little to optimize health and minimize illness burdens, especially for vulnerable groups. This failure to improve the underlying conditions for health is compounded by insufficient allocation of resources to address priority needs with equity (universality, accessibility and affordability). Finally, public health and primary health care are the cornerstones of sustainable health systems, and this should be reflected in the health policies and professional education systems of all nations wishing to achieve a health system that is effective, equitable, efficient and affordable.

Key Words: Health systems, Primary health care, Public health, Universality, Program integration, Social-ecological model, Professional education, Policy, Planning, Human resources

Introduction

This review is for two main audiences: clinicians and health care decision makers, two groups so focused on patient care and the administrative and financial challenges of illness management that they may overlook why people become ill in the first place, why they often present with advanced disease, why so many lack social support for their care, and what could be done to enhance their health prospects. The aim is to advocate for more integrated and universally accessible health systems, building on a sound foundation of primary health care (PHC) and public health (PH). The underlying rationale is the reality that health is mostly made in homes, communities and workplaces, and only a minority of ill-health can be repaired in clinics and hospitals [1].

Most health systems around the world remain heavily focused on illness and do relatively little to optimize health and thereby minimize the burden of illness, especially for vulnerable groups [2,3]. Failure to improve the underlying conditions for health is compounded by insufficient allocation of resources to address priority needs with equity (universality, accessibility and affordability). Instead, when engaged in public debate on health care, jurisdictions tend to focus on high-cost items that preoccupy administrators. This short-sighted focus overlooks ‘upstream factors’: health-promoting environments and workplaces, primary prevention, e.g., nutrition education, immunization, antenatal care, physical activity, smoking prevention, and social policies that influence literacy, employment, crime, housing quality, and community well-being. In particular, there is a global need to improve the response to the surging chronic disease burden. Research indicates that much of this burden is preventable by acting on modifiable behaviors, e.g., smoking, fitness, weight control; and about half of those who do develop these conditions can be prevented from progressing to complicated forms through attention to secondary prevention by identifying and engaging in early intervention for persons at risk, e.g., blood pressure screening and glucose monitoring. However, many decision makers remain preoccupied with acute-care issues, crisis-prone yet glamorized, even overlooking important ‘downstream considerations’, e.g., long-term care, home care, whose availability determines the speed with which acute-care patients may move to more appropriate levels of care.

Health Systems as the Frame of Reference

A health system comprises all organizations, institutions and resources whose primary intent is to improve health. In most countries, the health system is recognized to include public, private and informal sectors [4]. While the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes economic, fiscal and political management systems that underpin formally organized health services, it also recognizes the informal sector; this consists of self-help and care by families and communities, and the role of informal and traditional practitioners [5]. Health systems are about more than patient care: they attend to why people become ill in the first place, and foster health-promoting environments, and sound preventive practices. Implicit within the WHO approach is that nations must design and develop such integrated systems in accordance with their needs and resources.

All health systems, to be effective and efficient, must rest on strong foundations: first among these are properly designed and adequately funded and recognized components for PH and PHC. However, in many countries, these components are insufficiently developed, mirrored in inappropriate resource allocations across the health sector and with insufficient attention to the underlying health determinants. These flaws in health policy and management result in suboptimal health outcomes at the population level and are associated with deficiencies in related professional education and advanced training. Indeed, few nations have targeted higher education as a strategic element for improving population health, compounded by the fact (important to developing countries) that few development agencies have engaged institutions of higher education as strategic partners [6].

An insightful study of low- and middle-income countries that achieve good health outcomes at modest cost (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Tamil Nadu, and Thailand) has recently revealed 4 underlying determinants that drive successful health systems [7]. These are (1) capacity: the key role of individuals and institutions in designing and implementing reforms; (2) continuity: the stability required for reforms to be implemented, and the institutional memory that prevents mistakes from being repeated; (3) catalysts: the ability to make use of windows of opportunity, and (4) contexts: policies relevant and appropriate to circumstances. The study also identified the critical role of access to PHC, especially antenatal care and skilled birth attendants, and the high uptake of critical PH interventions: immunization, oral rehydration for diarrheal disease and modern contraception. The importance of sustained political support for health, a skilled health workforce, a high degree of community involvement, and health-promoting polices that go beyond the health sector was emphasized.

Terminology in Context

The terms ‘primary health care’ and ‘public health’, in common use, may carry different (often imprecise) meanings depending on context and perspective. In fact, many published studies into PHC do not even define it, leaving it up to the reader to interpret. For example, one literature search of >2,000 studies into PHC discovered that 46s% did not include a definition [8]. Such an approach is unscientific and renders systematic review problematic. For the purpose of this review, two definitions are recognized: the first is profession-centred, while the second, developed by the WHO, takes a societal perspective [9].

Defining PHC

Health or medical care that begins at time of first contact between a physician or other health professional and a person seeking advice or treatment for an illness or an injury.

Essential health care made accessible at a cost that a country can afford, with methods that are practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable. Everyone should have access to it and be involved in it, as should other sectors of society. It should include community participation and education on prevalent health problems, health promotion and disease prevention, provision of adequate food and nutrition, safe water, basic sanitation, maternal and child health care, family planning, prevention and control of endemic diseases, immunization against vaccine-preventable diseases, appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries, and provision of essential drugs.

While both PHC definitions are in common use, the ‘profession-centered’ one is usually taken to imply only ‘clinical contact’; it ignores the role of family members as first-line caregivers and accords no role to communities in addressing health [10]. It is only a partial definition (which is why it is often and more accurately referred to as ‘primary care’ or PC) [11]. Important as this clinical role may be, it is not the whole picture. By contrast, the WHO definition applies to the health system as a whole and recognizes the need to involve communities in their health. The WHO concept encompasses public policy, social and environmental elements, in addition to clinical care.

The literature points to the fact that PC (the clinical perspective) is associated with enhanced access to health services, better outcomes and a decrease in hospitalization and use of emergency visits. Clinical PC for the individual and the family (in this context also known as family medicine) represents the first contact in a health care system that should be characterized by continuity, comprehensiveness and coordination: providing individual, family-focused and community-oriented care for preventing, curing or alleviating common illnesses and disabilities, and promoting health [12].

A continuum thus exists within PHC from the individual to the nation, and it is legitimate to organize the response to health and social needs in complementary ways across this continuum. Thus, it is reasonable for clinicians to see their PC role in relation to the individual and the family, while equally so for PH agencies to address issues in terms of defined populations or society as a whole. Together, along with the roles of other entities such as community-based organizations, they contribute much of what can ultimately be considered PHC in its fullest sense. So what then is ‘public health’?

Defining PH

PH is society's response to threats to the collective health of its citizens. PH practitioners work to enhance and protect the health of populations by identifying their health problems and needs, and providing programs and services to address these needs [13].

PH is the art and science of promoting and protecting good health, preventing disease, disability and premature death, restoring good health when it is impaired by disease or injury, and maximizing the quality of life. PH requires collective action by society, collaborative teamwork by nurses, physicians, engineers, environmental scientists, health educators, social workers, nutritionists, administrators and other specialized professional and technical workers, and an effective partnership with all levels of government [14].

The Alma Ata Declaration as Historical Context

Careful reading reveals that the broader concept of PHC (definition 2) contains elements of both PC and PH. It grew out of an international conference in 1978 hosted by the WHO and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), which issued the Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care [15]. However, while the role of medical care was well appreciated, health policy analysts from developing nations were ahead of their developed country counterparts in attempting to bring integrated thinking to the development of PH systems [16], but this group enjoyed little support from donor countries which favoured selected disease control initiatives (‘vertical’ programming, often following a ‘command and control model’, driven from the ‘top’) over those based on participatory community development principles.

Both approaches were genuine attempts to improve health in developing countries, but the ensuing decades witnessed at least partial failure of both [17]. Local communities failed to develop integrated PHC, and often had to compete for priority and resources with vertically driven strategies heavily supported by donor nations. While some disease-specific initiatives achieved success, fundamental health determinants, such as clean water, food security and attending to locally prevalent conditions, fell by the wayside, with little change in overall population health status. With hindsight, this deficiency is now being acknowledged, and efforts are underway in some countries to enlist communities in defining their needs and solutions, approaching health systems development in a more respectful manner [10].

The Alma Ata Declaration's ill-fated slogan of ‘health for all by the year 2000’ was taken up at the turn of the century as an opportunity not to celebrate but to examine what went wrong with this noble goal, especially the failure to operationalize it. In particular, numerous critics drew attention to serious issues of equity in health care delivery and lack of fairness in health care management, noting the great need to transform management systems and practice, as concerns common to many countries [18]. In addition, the refusal of experts and politicians in developed countries to accept that communities should have a strong role in planning and implementing their own health care services is considered among the root causes of the problem [19]. The disproportionate influence donor nations have over global decision making, as they do over their development assistance policies, is also strongly linked to their strong preference to fund vertical initiatives, even as they have (collectively) not lived up to their pledges for assistance [20]. While there have been outstanding PH successes in the 20th century (reviewed in this journal) [21], as William Foege, former leader of the WHO's Task Force for Child Survival and Development, summed it up [22]: ‘Spectacular Progress, Spectacular Inequities!’

Clinical, Social and Environmental Approaches as Complementary Perspectives on Health

Ever since the dawn of medicine and PH, both of which have ancient roots, there has been controversy, even struggle, surrounding their relative importance, almost as if the two domains are competitive rather than cooperative and complementary [23]. Sir Michael Marmot, Chair of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, framed it thus in his 2006 Royal College of Physicians Harverian Oration: ‘A physician faced with a suffering patient has an obligation to make things better. If she sees 100 patients, the obligation extends to all of them. And if a society is making people sick? We have a duty to do what we can to improve the public health and to reduce health inequalities …’ [24]. Globally, social determinants strongly influence both health and equity, which vary enormously both between and within countries [25].

Similarly, the US National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, has stated on the foundations of health systems: ‘there is strong evidence that behavior and environment are responsible for over 70s% of avoidable mortality’ and ‘Health care is just one of the determinants’ [26].

But little of the contribution from the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health or that of the US National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, is really new thinking so much as revitalizing long-recognized truths buttressed by new data. Recalling Virchow, that ‘medicine is a social science, and politics is but medicine writ large’ [27], there is increasing recognition that policies outside the health sector are critical to health.

Moving beyond Health Policy to Healthy Public Policy

The developments outlined in the preceding paragraphs belong mostly within the traditional context of ‘health care policy’. However, if we are to follow the advocates from Virchow to Marmot, we must look beyond this to embrace a much larger domain: ‘healthy public policy’, which has evolved into a major movement to stimulate health-promoting policies around the world.

The term ‘healthy public policy’ may not be familiar to all readers of this journal. This does not mean ‘public health policy’, which relates primarily to the policies developed and implemented by a Ministry of Health. ‘Healthy public policy’ prescribes that ‘health’ must be on the agenda of all government ministries [28]. This recognizes the fact that healthy societies are a product of many forces beyond the health system per se: transport and environmental policies, food and nutrition policies, educational policies, and so on. Sound public health inter alia depends on healthy public policy. This is a virtually global policy shift that has grown out of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, sponsored by the WHO in 1986 [28]. Also referred to as ‘health in all policies’ [29], a critical element is that governments are ultimately accountable to their people for the health consequences of their policies, or lack thereof.

Regarding the intersectoral collaboration which underpins effective PHC and PH (including the promotion of healthy public policies), consider the improvements in health and life expectancy (LE) achieved in many regions during the past century. In Western industrial nations, LE increased from <45 to >75 years of age; epidemiological models reveal that 25 of the 30 years of LE added can be attributed to measures such as better nutrition, sanitation and safer housing. Although medical care contributed only 5 years of this gain in LE [30,31], when applied through a system that respects universal access, medical care is becoming more effective and relevant to population health: for example, a recent Canadian study [32] has revealed that (over a 25-year period) differences between the richest and poorest quintiles in expected years of life lost, amenable to medical care, decreased 60s% in men and 78s% in women, thereby narrowing the socioeconomic disparities in mortality experience.

To generalize from these convergent streams of thought and action, continuing disparities in health conditions between and within countries must be addressed by harnessing both the clinical and PH models; this is best done by taking a ‘whole of society’ approach [33], such that individual and collective action at all levels can be relevant and mutually reinforcing.

Applying the Social-Ecological Model to Health Systems Integration

In examining the overlaps and boundaries between PHC and PH, and indeed all other elements of an organized health system, it is useful to consider the ‘social-ecological model’ (SE Model) as a way of appreciating how people relate through family and community relationships to society as a whole. Analysis of the extent to which relationships are aligned and reinforcing holds potential for understanding the health outcomes that may arise both positive and negative. The model can also serve as an analytical framework, by which intervention strategies may be designed, implemented, monitored, and evaluated [34]. Indeed, its principles were applied in developing the landmark Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1984) [28], and utilized by the Institute of Medicine (US National Academy of Sciences) in their seminal work (2003) [35] on the future of PH in the 21st century. The SE Model is being applied by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in addressing violence in American communities [36] and to other PH issues; in both the USA and Australia, it lies at the core of efforts to address obesity [37,38]. Regardless of complexity, all variations of this model are conceptually similar, reflecting an evolving synthesis of epidemiology with social and behavioral sciences [39].

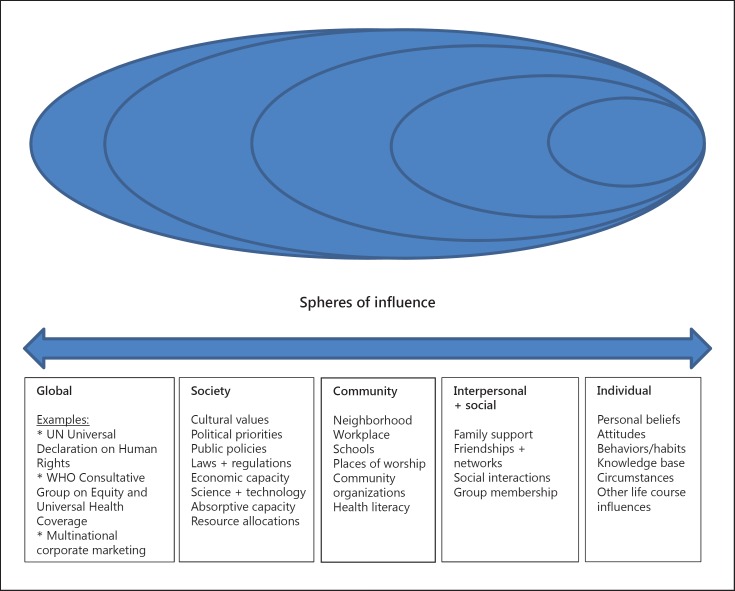

It can be appreciated that the illustrative SE Model (fig. 1) depicts interplay between individual, relationship, community, societal, and global influences. Thus, it may help structure ways of identifying the influences which place people at risk (or benefit) for various health and development outcomes across lifespans. An approach that incorporates complementary interventions at several levels is more likely to achieve and sustain success over time than a single intervention. The following are generic descriptions of what may be relevant at each level.

Fig. 1.

The social-ecological model – spheres of influence.

Individual: This first level identifies biological and personal factors, such as age, gender, education, income, and personal or family history. Prevention strategies at this level are designed to promote attitudes, beliefs and behaviors and may include education and life skills training. It is here that most clinicians place their energies, for individuals who come within their purview.

Relationship: The second level examines relationships that may increase or reduce a risk of experiencing a negative or positive outcome. A person's closest social circle (peers, partners and family) influences their behavior and contributes to their range of experience. Prevention strategies here may include mentoring and peer programs designed to reduce conflict, foster problem solving and promote healthy relationships. This role belongs to the social circle.

Community: The third level explores settings, such as schools, workplaces and neighborhoods, in which social relationships occur and seeks to identify characteristics of these settings that are associated with influence towards negative or positive outcomes. Strategies here are designed to impact context, processes and policies. For example, social marketing campaigns are often used to foster community climates that promote healthy relationships. To achieve success at this level normally requires much more than the efforts of one individual and may involve a community organization and/or could be taken up by a formally organized PH program.

Society: The fourth level looks at broad societal factors that help create a climate in which the health behavior in question is encouraged or inhibited, including social and cultural norms. Other large societal factors include the health, economic, educational, and social policies that help to produce or maintain the status quo, which may include unjustifiable economic and/or social inequalities between social groups. This level of intervention normally belongs to organized PH, although it may reach beyond this in the form of ‘healthy public policy’.

Global Influences: These cover a spectrum from UN Conventions to the often uncontrolled (potentially controllable) influence of corporate marketing, which may have health implications.

In synthesis, the essence of the SE Model is that while individuals are often viewed as responsible for what they do, their behavior is largely determined by their social and economic environment, e.g., community norms and values, regulations and policies. Barriers to healthy behaviors are often shared across their community, even a society as a whole; as these are lowered or removed, behavior change becomes more achievable and sustainable. The optimal approach to promoting healthy behaviors, therefore, may be a combination to reinforce efforts at all levels: individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy. This brings us to the challenge of how best to align the components and approaches that are mutually supportive.

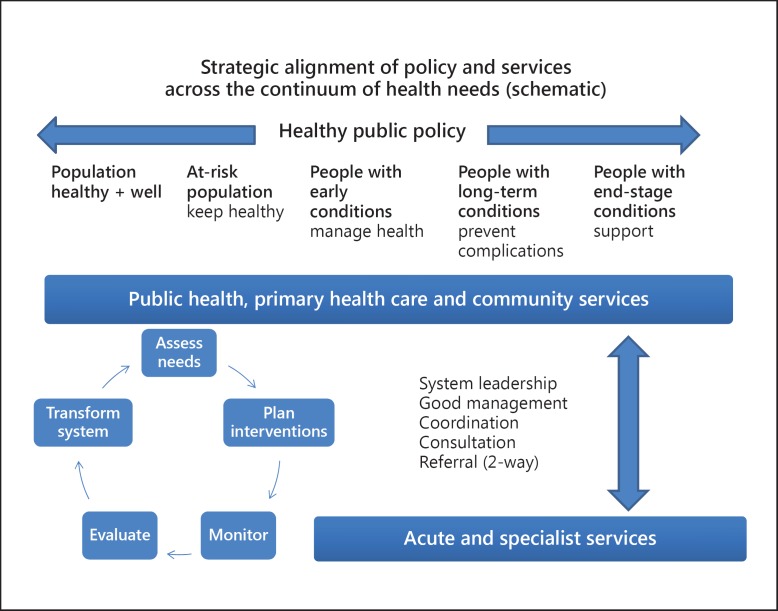

Drawing upon this approach to address the development of services relevant to a nation's population health, the strategic alignment of policy and services across the continuum of population health needs is important, as depicted in the schematic diagram (fig. 2). Thus it is appropriate to recognize ‘healthy public policy’ as the overall policy environment, with PH, PHC and community services as the crosscutting framework for all health and health-related services operating across the spectrum from primary prevention to long term care and end-stage conditions. This in turn must be integrated and coordinated with the critically necessary acute and specialist care system. Although this perspective is both logical and well grounded, the reality is different in most settings, and there is room for improvement everywhere. Indeed, there is a need to integrate health care (at all levels) with PH and PHC: to assess population health needs, set priorities, to plan and implement programs that will better meet the needs, keeping in mind that interventions from across the spectrum are critical to the achievement of desirable health outcomes: healthy public policies, environmental and occupational health protection, health promotion, clinical interventions, and integrative strategies to guide the development of PH and PHC strategies as well as more specialized and supportive care, all of which should be designed to respect the core principles of universality and sustainability [40].

Fig. 2.

Strategic alignment of policy and services across the continuum of health needs.

Universality as a Core Principle of an Integrated Health System

The achievement of universal access to health services, in the many countries where it now exists, has engaged a broad political debate in every instance, a debate that has become global in scope. Consider the statement of Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director General [41]: ‘I regard universal health coverage as the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer. It is inclusive. It unifies services and delivers them in a comprehensive way, based on primary health care’.

The goal of universal health coverage (UHC) is to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship when paying for them. The WHO states (verbatim):

‘For a community or country to achieve universal health coverage, several factors must be in place, including:

-

A strong, efficient, well-run health system that meets priority health needs through people-centred integrated care (including services for HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, non-communicable diseases, maternal and child health) by:

informing and encouraging people to stay healthy and prevent illness;

detecting health conditions early;

having the capacity to treat disease; and

helping patients with rehabilitation.

Affordability: a system for financing health services so people do not suffer financial hardship when using them. This can be achieved in a variety of ways.

Access to essential medicines and technologies to diagnose and treat medical problems.

A sufficient capacity of well-trained, motivated health workers to provide the services to meet patients' needs based on the best available evidence.

It also requires recognition of the critical role played by all sectors in assuring human health, including transport, education and urban planning.

Universal health coverage has a direct impact on a population's health. Access to health services enables people to be more productive and active contributors to their families and communities. It also ensures that children can go to school and learn. At the same time, financial risk protection prevents people from being pushed into poverty when they have to pay for health services out of their own pockets. Universal health coverage is thus a critical component of sustainable development and poverty reduction, and a key element of any effort to reduce social inequities. Universal coverage is the hallmark of a government's commitment to improve the wellbeing of all its citizens.

Universal coverage is firmly based on the WHO constitution of 1948 declaring health a fundamental human right and on the Health for All agenda set by the Alma-Ata declaration in 1978. Equity is paramount. This means that countries need to track progress not just across the national population but within different groups (e.g. by income level, sex, age, place of residence, migrant status and ethnic origin) [41].

Implementing Universality

UHC in the sense outlined has been advocated for decades. For example, in 1993, the World Bank stated that investing in health through basic health care and PH measures is an investment in any nation's human resource [42]. However, it has taken a long gestation for this idea to take hold. Since 2010, however, over 70 countries have requested policy support and technical advice for such a reform from the WHO. In 2011, the World Health Assembly responded by calling on the WHO to develop a plan of action for providing such support and advice. A WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage was set up to develop guidance on how countries can best address the central issues of fairness and equity that arise on the path to UHC. The following three-part operational strategy has recently been advocated, for which full details are available online from the reference cited [43]:

Categorize services into priority classes. Relevant criteria include those related to cost-effectiveness, priority to the worse off, and financial risk protection.

First expand coverage for high-priority services to everyone. This includes eliminating out-of-pocket payments while increasing mandatory, progressive prepayment with pooling of funds.

While doing so, ensure that disadvantaged groups are not left behind. These will often include low-income groups and rural populations.

The report addresses critical choices that arise on the path to UHC. It is about the path to that goal, addressing fundamental issues and difficult trade-offs. All health systems reflect the political and cultural values of a country, so the policy pathway will vary.

Taking Canada as a historic example: although health services are a provincial responsibility, the core features of Canadian health care are enshrined federally, in the Canada Health Act (1984), the aim being: ‘to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers’ [44]. Within this aim, 5 principles are upheld: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. From the patient's standpoint, with exceptions, such as home care, long-term care, dental care, physiotherapy and pharmaceuticals, the system is free of charges for hospital and medical care, thereby approaching the aim of ‘reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers’.

Globally, the question has arisen as to whether the principles of Canada's universal system have actually delivered desirable health outcomes for the Canadian population so far. In partial response to this question, a systematic review of 38 studies has recently confirmed that Canada's system leads to health outcomes that are favorable overall when compared with the US fragmented and mostly private for-profit system, at <50s% of the cost [45]. However, perhaps more relevant is the WHO's landmark study from 2000 of health systems performance in almost 200 countries, ranking the UK in 18th place, Canada in 31st place, and the US (the most expensive health care in the world) in 37th place. Most European countries performed better than Canada [46]. Several other countries also scored better than Canada, e.g., Singapore and Japan. The main lesson, therefore, is that all nations should learn from one another, especially from those systems which appear to be doing better, and are more prepared to innovate, test and evaluate new approaches.

Throughout a recent public consultation on a Canadian provincial health system (British Columbia), there was wide recognition that the keys to improving population health and gaining efficiencies throughout the health system lie within the scope of PHC and that prevention, demand management and self-management must all be addressed [47]. Lack of incentives for self-education and self-discipline became a recognized need, and ideas for improvement included: school health education, government-sponsored information packages, promoting the internet and other media as public information tools, translation of materials into minority languages, and extending education to rural communities through mobile facilities.

The most prominent example of a country only now embracing universal health care is the USA [4]. Historically, for those not included in employer-funded plans, health care in the USA has been dominated by high-cost health insurance that discriminated against those most in need. This resulted in almost 50 million people lacking any health insurance, many denied such coverage because of pre-existing conditions. Furthermore, the industry was permitted to set caps on lifetime payments regardless of medical need. Dominated by for-profit insurance schemes that treat health care as a commodity, most health care was allocated on the personal ability to pay. Among wealthy Western countries, only in the USA were such conditions still being applied in the 21st century. However, dramatic changes are now taking place: under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010 (‘Obamacare’). Implementation commenced in 2013, to be fully phased in by 2020. With this, the USA will finally begin to close the gap on universality and other deficiencies [4]. Lack of such a more equitable policy in the past constituted a major barrier to the health of its population: not only were many people excluded from levels of care considered normal in other advanced economies, but the system (when accessed for serious illness by an uninsured person) could force personal bankruptcy, such that many went without health care, with consequent threats to the public health due to gaps and delays in prevention, diagnosis and treatment (perhaps most obvious with regard to transmissible infections). Rectifying this systematic deficit in the health system simultaneously enhances PHC and PH. While poor planning has led to problems in initial implementation, the fact that the USA is now adopting universal health care as a public good is an overriding achievement.

From a global perspective, it is noteworthy that in 2000, a United Nations heads of government meeting issued a set of broadly defined Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [48]. In retrospect, this may be seen as a historic watershed in global policy development: people and their governments were expressing similar concerns and aspirations for more equitable solutions to achieve sustainable development. By 2010, while the global economic crisis had reversed development gains in some countries and appeared to have undermined donor support [49], when assessed in 2012, several MDG targets were found to have been met ahead of 2015, and there was significant progress on others [50], as recently reviewed in this journal [51]. With encouragement from this progress (which, for more sceptical observers, may have been unexpected), the passage in December 2012 of a General Assembly resolution on UHC reveals how this is now also becoming a global health objective. The resolution urged member states to develop health systems that avoid substantial direct payments at the point of delivery and to implement mechanisms for pooling risks to avoid catastrophic health-care spending and impoverishment [52]. UHC is now being proposed as a goal within the post-2015 MDG framework that puts rights and equity at the forefront for all nations [53]. If adopted, it will be difficult for any nation to avoid implementing UHC, however consistent this must be with its evolving political and cultural values.

While the health systems of most high-income countries embody the principles of UHC, only now is this being addressed in low- and lower-to-middle-income countries. Until now, these have been on the receiving end of global policies emphasizing selective goals, focused on controlling specific diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria and delivering specific interventions, e.g., immunization. Only in recent years has UHC attracted greater attention, being the subject of World Health Assembly and UN General Assembly resolutions, and is now advocated for inclusion in the post-2015 successor to the MDGs (to be named Sustainable Development Goals).

Aligning the Components of an Integrated Health Service

The WHO defines integrated service delivery as ‘organization and management of health services so that people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways that are user friendly, achieve the desired results and provide value for money’ [54]. One may thus contrast the more traditional approach of individual programs, doing their own policy planning and implementation, monitoring and evaluation, with the alternative of pooling common capacities to serve the needs of several programs. While individual programs may retain their own leadership and may have developed some strong capacities (while being deficient in others), the challenge of integrated programming is to develop and apply all needed capacities within a shared support framework so as to achieve synergy across programmatic objectives, to avoid duplication of resources, thereby to become mutually supportive and more effective at all relevant levels. Thus, integrated approaches call for interprogrammatic coordination to achieve more functional health systems, surely a justifiable goal [34].

Drawing from the sources referenced [34,54], the concept does not imply integrating everything into one package, or delivering services in one location. It means arranging services so that they are mutually supportive and easier for users to navigate, and that providers have support systems in place to help make this happen, while optimizing resource utilization. While the process may produce gains in efficiency that allow some resources to be redeployed, integration is mainly about doing things in a manner that should result in better outcomes: it is primarily a search for quality and should not be viewed as a solution for inadequate resource inputs. In evolving integrated services, change must be managed: people at all levels are asked to change the way they operate, including control over resources. Incentives may have to be altered.

Notwithstanding the need to develop more effective and efficient integrated models, there remain arguments in favor of discrete programming in particular settings and situations such as: short-term measures in fragile states, for the control of epidemics, for disaster management, and other unpredictable situations, so that appropriate services can be provided for groups affected in specific ways, e.g., refugees, displaced persons or communities facing extraordinary threats.

While the development of an integrated model may be desirable in the longer term, it may not always be possible to initiate this de novo. Reviewing the health situation of a low-to-middle-income country in the late 1990s to help design an integrated noncommunicable disease program, it quickly became clear to the author that, aside from the work of individual physicians and relevant health education efforts of the Ministry of Health, the building blocks for an integrated approach were mostly undeveloped. As a first step, therefore, these components needed strengthening, before they could be integrated. There is little purpose in embarking on a perceived solution to problems unless there is leadership and organizational capacity to carry it forward: this is sometimes referred to as ‘absorptive capacity’ [55].

Implications for Health Professional Education

The perspective outlined in this review aligns with the views of the Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century, a global body that projected a vision that all health professionals should be educated so as to ensure their competence to participate in both patient- and population-centred health systems [56]. It is consistent with requirements for medical accreditation, such as those of the UK [57], the USA and Canada [58], in recognizing the determinants of health in training programs. It echoes the spirit of Flexner, whose lasting contribution to medical education was celebrated on its centennial in 2010 [59]. His legacy was 2-fold: that medical education must be founded on scientific evidence, and that it must strongly emphasize PH and social (as distinct from business) principles.

Although this review gives purposeful recognition to the value of Flexner's advocacy regarding medical professional education, this was over a century ago and it is important to recognize that the world today is vastly more complex than it was then. Health professionals, rather than being trained exclusively in hospitals and clinics where they encounter an array of sick people, also need to understand how health is really ‘produced’ in homes, communities and in how people live and work. All health professionals are expected to work as team members, and physicians are not always the appropriate leaders: they have to accept coordination by other members of the team when appropriate. It is, therefore, important to expand medical education well beyond the hospital-based model as the exclusive way to learn clinical medicine, and increasingly utilize community-based and multidisciplinary placements, including PHC and PH settings. These will reflect more the realities of life and offer avenues through which to learn about continuity and to promote teamwork, mentoring and professional development. To quote the Josiah Macy Foundation: ‘Good health care is more than the provision of clinical services. Today's doctors must learn new content and skills, including quality improvement, patient safety, communication, health economics, and the social determinants of health.’ [60]

The Role of an Ethical Private Sector in Partnership with the Public Sector

As for Flexner's historical contribution, he argued that business ethics was incompatible with the values necessary for socially useful medical education [61]. Consider the following quote: ‘Such exploitation of medical education is strangely inconsistent with the social aspects of medical practice. The overwhelming importance of preventive medicine, sanitation, and public health indicates that in modern life the medical profession is an organ differentiated by society for its highest purposes, not a business to be exploited’ [62].

This admonition duly recognized, the value of an appropriately involved private sector (within a policy framework) is becoming recognized as a resource to be tapped in the interests of population health, especially in the real world where public resources are increasingly constrained. In many developing countries, due to public sector underfunding, there would be virtually no health care at all for most people without the private sector in all forms, including public private partnerships (P3s) [4]. In some countries, health reform involving the private sector has uplifted people in a manner not achieved by the public sector, as illustrated by the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank, Bangladesh, for ‘efforts to create economic and social development from below’ through microcredit for the poor [63]. In transitioning from a centrally planned economy, Vietnam has involved the private sector in safe motherhood and family planning using policy and regulatory frameworks, while reviving a commune-level PH system to meet other basic needs. In the Central Asian Republics and Mongolia, formerly socialist regimes, building a private sector is a priority, including family physicians in group practices, effective referral systems in rural areas and autonomous boards managing hospital services [64]. In other developing nations, benefits are emerging: subsidized products, distribution assistance, educational initiatives, and disease control, e.g., Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI). Some P3 models are effective in the development of community health systems, e.g., BRAC (Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee) initiated an integrated health program, linking foundations, governments and communities.

Furthermore, the WHO-sponsored Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World (2005) [65] noted that the corporate sector directly impacts on the health of people and on the determinants of health through its influence on: local settings, cultures, environments, and wealth distribution. It declares that the promotion of health should be a requirement for good corporate practice. Inter alia, this recent Charter (building on the Ottawa Charter) states that:

‘The private sector, like other employers and the informal sector, has a responsibility to ensure health and safety in the workplace, and to promote the health and well-being of their employees, their families and communities. The private sector can also contribute to lessening wider global health impacts, such as those associated with global environmental change by complying with local, national and international regulations and agreements that promote and protect health. Ethical and responsible business practices and fair trade exemplify the type of business practice that should be supported by consumers and civil society, and by government incentives and regulations’ [65].

Change as the Challenge

Although the main aim of this review was to advocate for more integrated and universally accessible health systems, from a management perspective, the paper is also about the need for change and how to manage it: divesting ourselves of tired old hierarchical concepts which have roots in a ‘command and control approach’ to relationships – the notion that health systems should be organized and run in a pyramidal manner, with specialized commodities accorded greater prestige and placed at the apex and with more fundamental ones at the base, ostensibly serving the needs of those higher in the hierarchy. This mode of thinking is virtually feudal in its origins and sadly, is still with us in the 21st century, even though it is not commensurate with a world of instant access to information, matrix management and interprofessional networking, and where authentic leadership and collegiality are needed at every level of the system.

Here is some of what the Dean of Public Health at Harvard University, having traced the modern origins of primary care to the Dawson report in the UK in 1920, has to say about this:

‘Much of the failure of primary health care and the need for renewal are attributable to the origins of the pyramidal structure of care. The notion of primary, secondary, and tertiary levels seems to have been borrowed from education. This original fusion is the source of much confusion. Indeed the equivalence between primary care and primary education is flawed for two main reasons. First, in health matters there is no linear progression from simple to complex problems over the life of an individual. A person might have a complex life-threatening disease, such as cancer, and subsequently come down with a common cold. In the formal educational system, students progress in a sequential manner toward graduation. The only graduation from the health system is death. Second, in health there is always an element of uncertainty that is absent in educational services, which can be programmed in a fairly straightforward way. Importing the educational idea of primary into the health domain led to a false sense of simplicity around primary health care’ [66].

The anachronistic mode of organizational thinking just described continues to have damaging consequences for health systems development: it also cannot be justified if one respects the Flexnerian legacy that medicine must be both evidence-based and emphasize PH and social principles. The existing overemphasis on increasingly narrow specialization poses disadvantages for any society. Lacking continuity for individuals and families, this contributes to fragmented health care, and creates confusion; it is also a more costly way of doing things.

Yet, much of this can be resolved by recommitting health systems development to a foundation that is strongly centered in PHC and PH and that creates integrated referral pathways through which interventions at every level have a greater potential for both coherence and mutual reinforcement. A general case in favor of more integrated policy and management of health systems therefore seems to be almost intuitive, whereby programs are developed and implemented within a common framework so as to be mutually supportive. Yet being ‘intuitive’ is never enough: expanding access to priority health services requires the concerted use of all modes of delivery, according to the evolving capacity of health systems as they change over time [67]. Such evolution should not be left up to the marketplace: it must be guided by leadership that takes into account the health needs of the population as a whole.

It is appropriate now to take note of a similarity between the evolving debate regarding the relative merits of ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ programming in developing countries, referred to earlier in this paper (see The Alma Ata Declaration as Historical Context), and the design of health systems in more developed ones where there is a comparable struggle for balance between the roles of highly specialized care (and professional education systems that heavily favor this) and a less well-supported system of PHC and PH. As the case for universal health care takes hold in both contexts, this should add momentum to a process of convergence that should result ultimately in more effective and equitable health systems.

Likewise, in responding to the challenge of integrating health service components within a greater functional system, as the author has noted elsewhere [34]:

‘In advocating a transition to more integrated approaches, resistance will be encountered and legitimate concerns need to be addressed, especially to reassure ‘single disease’ champions more familiar with traditional stand-alone initiatives. In this respect, unique and important aspects of particular conditions must receive the priority they deserve, and not lost in the process; in some instances stand-alone programs will remain justifiable. Success in transforming separately organized programs into a more integrated model requires vision and guidance from leadership and management levels, as well as a training strategy that will instill new knowledge, skills and attitudes to front-line staff. This process should be guided by evidence, and a commitment to monitoring and evaluation’ [34].

Globally, there is reason for encouragement regarding health systems development as witnessed by the support from the WHO for universal health care, and numerous regional efforts ranging from ‘Obamacare’ in the USA (both reviewed in this article), to developments in the Middle East, such as Kuwait University launching a Faculty of Public Health in 2014 and the designation of its Faculty of Dentistry as a WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Primary Health Care [68,69].

Conclusion

Whenever seriously addressed as a matter of health policy, PH and PHC are considered essential and sustainable cornerstones in building a sustainable health system for the 21st century. However, despite a virtual global consensus that these are the most critical components, there is considerable imbalance in the priority accorded to them in health policy and in higher education in most countries. There are numerous reasons for this, ranging from the dominance of an outmoded industrial view of health services development that favors specialized biotechnologies over a better understanding of health determinants that could lead to improved prevention strategies, to the motivations behind particular career choices, influenced as these often are by consideration of remuneration, lifestyle and personal prestige. It is, therefore, important for policy makers and health leaders in all countries to identify the needed roles from a health systems standpoint, to plan for a more integrated approach, and to adjust strategic incentives to achieve the changes that are so clearly needed. Clearly, there is an imperative to design training, recognition and reward systems that recognize contributions that meet the real needs of people and society as a whole. This requires reemphasizing PHC and PH and attracting professionals into them as broad disciplines in their own right with a body of science and skills. These disciplines are the cornerstones of sustainable health systems, and this should be reflected in the health policies and professional education systems of all nations wishing to achieve a health system that is effective, equitable, efficient, and affordable.

Acknowledgements

Debra Nanan, MPH, Pacific Health & Development Sciences Inc., critiqued an early draft and the penultimate version and provided ideas for the development of figure 2. Dr. Joseph Longenecker, Kuwait University, encouraged this review's development. Views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of Victoria and Dalhousie University.

References

- 1.White F, Nanan D. Community health case studies selected from developing and developed countries – common principles for moving from evidence to action. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:358–363. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikari NKJ, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376:1339–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White F, Nanan DJ. International and global health. In: Wallace RB, Kohatsu N, editors. Maxcy-Rosenau-Last. Public Health and Preventive Medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 1251–1258. chapt 76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.White F, Stallones L, Last JM. Global Public Health – Ecological Foundations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. chapt 8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Health topics. Health systems. 2010 http://www.who.int/topics/health_systems/en/ (accessed September 17, 2014).

- 6.Freeman P. Why health professions education in the Journal of Public Health Policy? J Public Health Policy. 2012;33:S1–S2. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balabanova D, McKee M, Mills A.Good health at low cost. 25 years on. What makes a successful health system? London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2011 http://ghlc.lshtm.ac.uk/files/2011/10/GHLC-book.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 8.Ramirez NA, Ruiz JP, Romero RV, Labonte R. Comprehensive primary health care in South America: contexts, achievements and policy implications. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:1875–1890. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011001000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Last JM, editor. A Dictionary of Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.White F, Stallones L, Last JM. Global Public Health – Ecological Foundations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. chapt 4: community foundations of public health. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Misener R, Valaitis R, Wong ST, et al. A scoping literature review of collaboration between primary care and public health. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13:327–346. doi: 10.1017/S1463423611000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi L.The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.6064/2012/432892 (accessed June 19, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Public Health Agency of Canada. Pan Canadian Public Health Network Guidelines for MPH programmes in Canada. 2009. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/php-psp/mphpg-mhplg/index-eng.php (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 14.Last JM, editor. Preface. Dictionary of Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care. http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 16.Thunhurst CP. Public health systems analysis – where the River Kabul meets the River Indus. Global Health. 2013;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John TJ, White F. Public health in South Asia. In: Beaglehole R, editor. Global Public Health: A New Era. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 172–190. chapt 10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaikh BT, Kadir MM, Pappas G. Thirty years of Alma Ata pledges: is devolution in Pakistan an opportunity for rekindling primary health care? J Pakistan Med Assoc. 2007;57:259–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall JJ, Taylor R. Health for all beyond 2000: the demise of the Alma-Ata Declaration and primary health care in developing countries. Med J Australia. 2003;178:17–20. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White F. Development assistance for health – donor commitment as a critical success factor. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(6):421–423. doi: 10.1007/BF03404191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White F. The imperative of public health education: a global perspective. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22:515–529. doi: 10.1159/000354198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans T.An optimist's view of global health achievement. The Rockefeller Foundation blogsite http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/blog/optimists-view-global-health (accessed March 31, 2014).

- 23.Gottleib LM. Learning from Alma Ata: the medical home and comprehensive primary health care. J Am Broad Fam Med. 2009;22:242–246. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.03.080195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot M. Health in an unequal world. Lancet. 2006;368:2081–2094. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization Commission on the social determinants of health http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/ (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 26.Institute of Medicine . The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. November 2002. Washington: National Academy of Sciences; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor R, Rieger A. Rudolf Virchow on the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia: an introduction and translation. Sociol Health Illn. 1984;6:201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion. Ottawa 21 November 1986 – WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1. http://www.mecd.gob.es/dms-static/574eadc8-07b6-450f-b5b2-085ff1e201c8/ottawacharterhp-pdf.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 29.Rudolph L, Caplan J, Ben-Moshe K, et al. Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments. Washington and Oakland: American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute; 2013. http://www.apha.org/NR/rdonlyres/882690FE-8ADD-49E0-8270-94C0ACD14F91/0/HealthinAllPoliciesGuide169pages.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunker J. Improving health: Measuring effects of medical care. Milbank Q. 1994;72:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder SA. We can do better – improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1221–1228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James PD, Wilkins R, Detsky AS, et al. Avoidable mortality by neighbourhood income in Canada: 25 years after the establishment of universal health insurance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:287–296. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.047092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubé L, Thomassin P, Beauvais J.A ‘Whole-of-Society’ approach to an integrated health and agri-food strategy, in Discussion Paper – Building Convergence Toward an Integrated Health and Agri-Food Strategy for Canada. The Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute, 2009. Official Website. http://www.capi-icpa.ca/converge-summ/five.html (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 34.White F, Stallones L, Last JM. Global Public Health – Ecological Foundations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. chapt 6: integrated approaches to disease prevention and control. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine . The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. November 2002. Washington: National Academy of Sciences; 2003. http://www.iom.edu/∼/media/Files/Reports%20Files/2002/The-Future-of-the-Publics-Health-in-the-21st-Century/Futures%20ofs%20Publicss%20Healths%202002s%20Reports%20Brief.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Addressing obesity disparities. Social ecological model http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/addressingtheissue.html (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 38.Co-Ops Collaboration (funded by the Department of Health and Ageing, Australia) Links between the socio-ecological model and Ottawa Charter. http://www.coops.net.au/Pages/newsletter_articles/promising_interventions.aspx (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 39.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(4):668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaikh BT, Kadir MM, Hatcher J. Health care and public health in South Asia. Public Health. 2006;120:142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization What is universal health coverage. Online resource. October 2012. http://www.who.int/features/qa/universal_health_coverage/en/ (accessed March 29, 2014).

- 42.World Bank . World Development Report 1993: Investing in health. World development indicators. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. http://wdronline.worldbank.org/worldbank/a/c.html/world_development_report_1993/abstract/WB.0-1952-0890-0.abstract1 (accessed June 14, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage, 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112671/1/9789241507158_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed May 26, 2014).

- 44.Madore O.The Canada Health Act: overview and options. Economics Division. Parliamentary Information and Research Service. Government of Canada. June, 2003. http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/lop/researchpublications/944-e.htm (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 45.Guyatt GH, Devereaux PJ, Lexchin J, et al. A systematic review of studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the United States. Open Med. 2007;1:e27–e36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization The World Health Report 2000. June 21, 2000. http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/index.html (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 47.White F, Nanan D. A conversation on health in Canada: revisiting universality and the centrality of primary health care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32:141–149. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31819941f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2003. Millennium Development Goals . A compact among Nations to End Human Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2003 (accessed June 19, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.UN General Assembly 65th Session Agenda Items 115. Special Session on the MDGs. Outcome Document. September 2010.http://www.un.org/depts/dhl/resguide/r65_en.shtml (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 50.United Nations The Millennium Development Goals Report 2012. http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Static/Products/Progress2012/English2012.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 51.White F. What's new in public health? Med Princ Pract. 2012;21:505–507. doi: 10.1159/000342566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vega J. Universal health coverage: the post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2013;9862:179–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vega J, Frenz P. Integrating social determinants of health in the universal coverage monitoring framework. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34:468–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waddington C, Egger D. Integrated Health Services – What and Why? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Technical Brief No. 1 http://www.who.int/healthsystems/technical_brief_final.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 55.White F.Circulatory disease in the Americas: strategic opportunities for prevention and treatment. Conference on Global Shifts in Disease Burden: The Cardiovascular Disease Pandemic. Pan American Health Organization, National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, and the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health. May 26–28, 1998. Washington. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260229271_PLENARY_ADDRESS_Circulatory_Disease_in_the_Americas_strategic_opportunities_for_prevention_and_treatment?ev=prf_pub (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 56.Bhutta ZA, Chen L, Cohen J, et al. Education of health professionals for the 21st century: a global independent Commission. Lancet. 2010;375:1137–1138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.General Medical Council Tomorrow's doctors. 2009. http://www.gmc-uk.org/TomorrowsDoctors_2009.pdf_39260971.pdf (accessed February 25, 2012).

- 58.Liaison Committee on Medical Education Functions and structure of a medical school: standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD degree. 2013. http://www.lcme.org/functions.pdf (accessed April 24, 2013).

- 59.Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner Report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85:211–219. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The Josiah Macy Junior Foundation website http://macyfoundation.org/news/entry/100-years-after-flexner-medical-education-ushers-in-new-era-of-reform (accessed June 14, 2014).

- 61.Beck AH. STUDENT JAMA. The Flexner report and the standardization of American medical education. JAMA. 2004;291:2139–2140. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yunus M. Micro-Lending and the Battle against World Poverty. New York: Public Affairs Books; 2003. Banker to the Poor. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nayani P, White F, Nanan D. Public-private partnership as a success factor for health systems. Med Today. 2006;4:135–142. [Note: Medicine Today shut down in 2008; pdf available at: http://www.phabc.org/modules.php?name=Contentpub&pa=showpage&pid=36 (accessed June 19, 2014)]. [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World. 2005. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/6gchp/hpr_050829_s%20BCHP.pdf (accessed June 19, 2014).

- 66.Frenk J. Reinventing primary health care: the need for systems integration. Lancet. 2009;374:170–173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oliveira-Cruz V, Kurowski C, Mills A. Delivery of priority health services: searching for synergies within the vertical versus horizontal debate. J Int Development. 2003;15:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuwait University. Health Sciences Centre What's New. Faculty of Public Health http://www.hsc.edu.kw/FOPH/

- 69.Behbehani JM. Faculty of Dentistry, Kuwait University, designated as a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Primary Oral Health Care. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23(suppl 1):10–16. doi: 10.1159/000357125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]