Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the level of uric acid (UA) in saliva, which is considered to be an antioxidant defense biomarker against oxidative stress in patients with oral lichen planus (OLP).

Subjects and Methods

In this case-control study, 25 OLP patients were included. The reticular form of OLP was verified by a clinical examination with Wickham striae, and other types (erosive, atrophic, ulcerative) were confirmed by histopathological assessment. Thirty healthy individuals matched for age and gender were selected as the control group. In both groups, the Navazesh technique was used to collect the unstimulated saliva. Then, the amount of UA was measured using a Cobas Mira autoanalyzer with a wavelength of 546 nm. The Student t test was used to analyze the data assuming a significance level at <0.05.

Results

Of the 25 patients, the most common type of OLP was erosive (n = 11, 44%), and the most common site of OLP was seen as bilateral in the buccal mucosa (n = 12, 48%). The mean level of salivary UA was significantly lower in the patients with OLP (2.10 ± 0.19 mg/dL) in comparison with the control group (4.80 ± 0.29 mg/dL; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In this study, OLP was associated with a decrease in UA levels in the saliva. Salivary UA as a biomarker could be used for monitoring and treating OLP.

Key Words: Oral lichen planus, Saliva, Uric acid

Introduction

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is considered to be a premalignant disorder and is regarded as a relatively common mucocutaneous disease [1], the exact etiology of which is still unclear [2]. Lymphocytic infiltration and keratinocyte apoptosis has been observed to likely promote the activation of a cell-mediated immune response [3]. It has been suggested that the occurrence of OLP could be triggered by imbalances among the antioxidant stress markers in biological body fluids, and thus could play an important role in the pathogenesis of OLP transformation [4,5]. An oxidative metabolism can lead to oxidative stress as a harmful byproduct and molecular destruction in living systems, which are subsequently involved in numerous processes, such as aging, mutagenesis, and a series of pathological events [6].

Oxidative stress in OLP releases molecules consisting of granzymes that may result in local tissue damage in the effectors [7]. Antioxidants can defend against oxidative stress and are present in mammalian cells, such enzymes as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, as well as nonenzymatic antioxidants, including melatonin, uric acid (UA), and vitamins A and E [8,9].

As a scavenger of oxyradicals and chelator of metal ions, UA is known to be an important antioxidant that is predominant in plasma [10,11]. In the current study, saliva testing was utilized since a linear relationship exists between its UA concentration and serum. It is considered to be a helpful noninvasive fluid for the monitoring of biomarkers [12,13]. However, limited data are found in the literature about the UA level of saliva in OLP. Thus, to our knowledge, this study is the first such investigation to be conducted in Iran.

Subjects and Methods

This case-control study was performed on Iranian patients admitted to the Oral Medicine Department and also enrolled healthy volunteers. Informed consents were obtained along with ethical committee approval.

Selection of Patients

Twenty-five patients with OLP (cases), including 15 women and 10 men, and 30 healthy subjects (controls), including 20 women and 10 men, were compared. The reticular form of OLP was verified by a clinical examination with Wickham striae, while other types (erosive, atrophic, ulcerative) were confirmed by histopathological assessment. Histopathological confirmation was carried out according to the WHO criteria [14].

The exclusion criteria were the presence of any systemic disease (gout, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, heart disease, kidney disease, hepatitis C), alcohol consumption, smoking, the consumption of drugs that increase UA (e.g. antidiuretics), immunosuppressive drugs, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic or topical corticosteroids, vitamin supplements over the past month, a history of surgery or trauma in the past month, and having been treated for lichen planus or currently undergoing treatment [15].

Collection of Saliva

The patients refrained from eating and drinking for 2 h prior to sampling. Then, between 9 and 12 a.m., 2 mL of unstimulated saliva was collected from both groups through a spitting method [16]. The samples were immediately stored at −70°C. Centrifugation (Behdad Chemical Co., Tehran, Iran) of the test samples at 1,008 g was then performed for 10 min to separate the supernatant in order to measure the UA antioxidant using a Pars Azmun kit made in Iran. The results were recorded with the help of a trained impartial person.

UA Antioxidant Measurement

The level of UA activity in the saliva was determined based on the tooth colorimetric method (N-ethyl-N-[2-hydroxy-3-sulfopropyl]-3-methylaniline). A sample of 100 mM phosphate buffer of the reagent No. 1, pH 7.1, 1 mM TOOS, and 1 kU/L ascorbate oxidase was added to 20 μL of each sample. Incubation of the reaction mixture was conducted for 5 min at 37°C. Then, the samples were combined with 100 mM phosphate buffer of reagent No. 2, pH 7.0, 0.3 mM 4-aminoantipyrine, 0.1 μM K4 (Fe[CN]6), 1 kU/L peroxidase, and 50 kU uricase, and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The amount of UA was measured by photometry using a Cobas Mira autoanalyzer at a wavelength of 546 nm [17].

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software v.18.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used. The Student t test was used to analyze the data at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

The mean ages of the patients with OLP and controls were 46 ± 2.33 and 36 ± 1.18 years, respectively. Seven (28%) patients had reticular OLP that was confirmed clinically, and 18 (72%) patients were diagnosed with erosive, atrophic, or ulcerative OLP according to biopsy assessment. Among the patients, the most common type of OLP was erosive (11, 44%), and the most frequent site of OLP was seen as bilateral in the buccal mucosa (12, 48%). The frequency and number of OLP types and their locations in the oral mucosa are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Types of OLP in the case subjects, n (%)

| Reticular | 7 (28) |

| Erosive | 11 (44) |

| Atrophic | 4 (16) |

| Ulcerative | 3 (12) |

| Total | 25 (100) |

Table 2.

The location of OLP in the case subjects, n (%)

| Buccal mucosa (both sides) | 12 (8) |

| Buccal mucosa (1 side) | 4 (6) |

| Buccal mucosa (both sides) + tongue | 4 (6) |

| Buccal mucosa (both sides) + vestibular | 1 (4) |

| Tongue | 1 (4) |

| Vestibular mucosa | 1 (4) |

| Mandibular ridge | 1 (4) |

| Lip | 1 (4) |

| Total | 25 (100) |

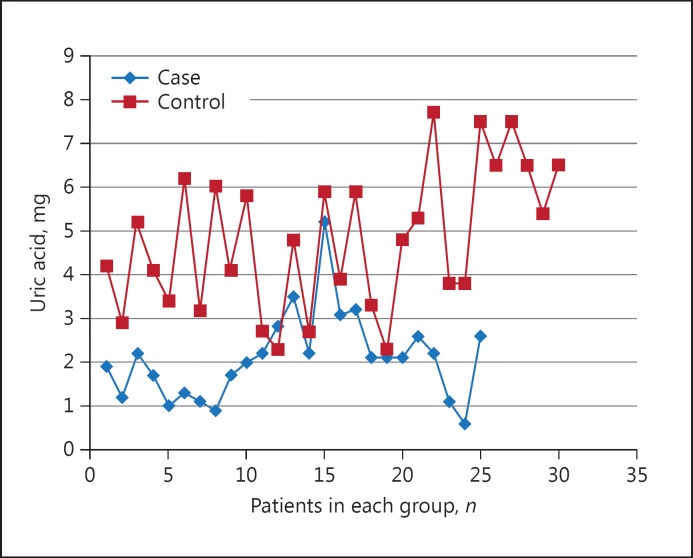

The mean salivary UA in the case group (2.10 ± 0.19 mg/dL) was significantly lower than that in the control group (4.80 ± 0.29 mg/dL; p < 0.001). The comparison of salivary UA in the cases and controls is presented as a scatter plot in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Salivary UA in the cases and controls.

Discussion

In this study, the level of salivary UA in the OLP patients was lower than in the control subjects. This finding confirmed that of Miricescu et al. [18], who reported lower UA levels in unstimulated saliva from OLP patients compared to the control group. Of equal importance, lower blood UA levels were found in patients with cutaneous lichen planus in comparison with the control group in the study by Chakraborti et al. [19]. Moreover, Miricescu et al. [18] detectedlower UA and total antioxidant capacity levels in the saliva of smokers and OLP patients involved in periodontitis compared to the control group.

Regarding the monitoring of some antioxidants, such as UA, bilirubin, glutathione peroxidase, and vitamin C in OLP patients who also presented cutaneous lesions, Barikbin et al. [15] found only decreased levels of vitamin C in the blood compared to the control group. In our study, in which we used saliva instead of blood, only UA demonstrated a significant decrease.

OLP occurrence has been suggested to be triggered by an enhanced oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system imbalance in biological body fluids, thus reflecting the pathogenesis of OLP transformation. As a scavenger of oxyradicals and chelator of metal ions, UA is known to be an important antioxidant. It is also a predominant antioxidant in plasma [10,11].

UA is an end product of purine metabolism and is produced in mammalian systems. It contaminates free radical substances through the inhibition of endothelial function under conditions of oxidative stress inside the cell in which glutathione is discharged [20]. It can further inhibit the ability of exogenous peroxynitrite to uncouple endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase. New compounds, such as peroxynitrite, are formed to further damage cells through the interface of NO with such oxygen radicals as superoxide [21]. Nevertheless, intracellular NO levels can be reduced by high UA concentrations [10].

It is thus suggested that an optimal strengthening of antioxidant defense be administered at the UA level as a treatment guideline since a major factor in the etiopathogenesis of lichen planus is deemed to be induced by free radical damage. Our findings were indicative of a reduced antioxidant UA level in OLP patients, and further investigation is warranted on a greater number of patients to assess other antioxidants and oxidative stress biomarkers for the treatment of oxidative stress in OLP, which we have shown to be likely associated with the depletion of salivary UA levels.

Conclusion

Our study showed that OLP was associated with decreased UA levels in saliva. UA could be a useful antioxidant biomarker for monitoring and guiding the treatment strategy in OLP. Hence, further studies are needed to compare and monitor the level of UA in treated patients over time.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was based on an undergraduate thesis. The authors wish to thank the Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the Dermatology Department in Shohada Hospital, Tehran, Iran, for their beneficial support, and Dr. Fateme Mashhadi Abbas for the assessment of biopsied specimens.

References

- 1.Glick M, Feagans WM. Burket's Oral Medicine. ed 12. Shelton: People's Medical; 2015. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munde AD, Karle RR, Wankhede PK, et al. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: a retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:181–185. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornhill MH. Immune mechanisms in oral lichen planus. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:174–177. doi: 10.1080/000163501750266774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ergun S, Troşala SC, Warnakulasuriya S, et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidant profile in patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aly DG, Shahin RS. Oxidative stress in lichen planus. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2010;19:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ScrobotăI I, Mocan T, Cătoi C, et al. Histopathological aspects and local implications of oxidative stress in patients with oral lichenplanus. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52:1305–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagler RM, Klein I, Zarzhevsky N, et al. Characterization of the differentiated antioxidant profile of human saliva. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Momen-Beitollahi J, Mansourian A, Momen-Heravi F, et al. Assessment of salivary and serum antioxidant status in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:557–561. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gersch C, Palii SP, Kim KM, et al. Inactivation of nitric oxide by uric acid. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:967–978. doi: 10.1080/15257770802257952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutzing MK, Firestein BL. Altered uric acid levels and disease states. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soukup M, Biesiada I, Henderson A, et al. Salivary uric acid as a noninvasive biomarker of metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakhtiari S, Toosi P, Dolati F, et al. Evaluation of salivary secretor status of blood group antigens in patients with oral lichen planus. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:266–269. doi: 10.1159/000442291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mravak-Stipetić M, Lončar-Brzak B, Bakale-Hodak I, et al. Clinic pathologic correlation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a preliminary study. Sci World J. 2014;2014:746874. doi: 10.1155/2014/746874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barikbin B, Yousefi M, Rahimi H, et al. Antioxidant status in patients with lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:851–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navazesh M, ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science How can oral health care providers determine if patients have dry mouth? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:613–620. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bablok W, Passing H, Bender R, et al. A general regression procedure for method transformation: application of linear regression procedures for method comparison studies in clinical chemistry, part III. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1988;26:783–790. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1988.26.11.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miricescu D, Greabu M, Totan A, et al. The antioxidant potential of saliva: clinical significance in oral diseases. Molecules. 2011;4:5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborti G, Biswas R, Chakraborti S, et al. Altered serum uric acid level in lichen planus patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:558–561. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.143510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamsi FA, Hadi SM. Photoinduction of strand scission in DNA by uric acid and Cu(II) Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:189–196. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00004-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panjwani S, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, et al. Estimation and comparison of levels of salivary nitric oxide in patients with oral lichen planus and controls. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:710–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]