Abstract

Objective

To report on the clinical benefits of platelet gel application in a non-regenerating skin wound.

Clinical Presentation and Intervention

An 84-year-old man presented with a severe wound with a regular circumference in the frontal region which resulted in a complete loss of epidermis and dermis. The skin lesion, induced by cryosurgery used to remove a basal-cell carcinoma, had previously been treated with a dermal substitute application (Integra®). After the failure of the skin graft, the patient was treated using a platelet gel therapeutic protocol which achieved the complete healing of the injured area.

Conclusion

This case showed the clinical efficacy of using platelet gel in this elderly patient in whom the dermal substitute graft had been ineffective.

Key Words: Growth factors, Platelet gel, Non-regenerating cryosurgery-induced lesions, Skin wound

Introduction

Physiologically, platelets are the first line of defence when a tissue injury occurs [1,2,3]. The greater part of the platelet secretome is stored in α-granules which contain haemostatic, angiogenic, anti-angiogenic, necrotic factors, growth factors and proteases [4]. For this rationale, platelet derivatives such as platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel (PG) act like a biomolecular cocktail to promote wound healing, angiogenesis, and tissue remodelling, bringing back the skin balance towards synthesis and cell proliferation [5,6]. Hence, we report a successful case of complete healing with the application of PG in a non-regenerating skin wound after the failure of dermal substitute application.

Case Report

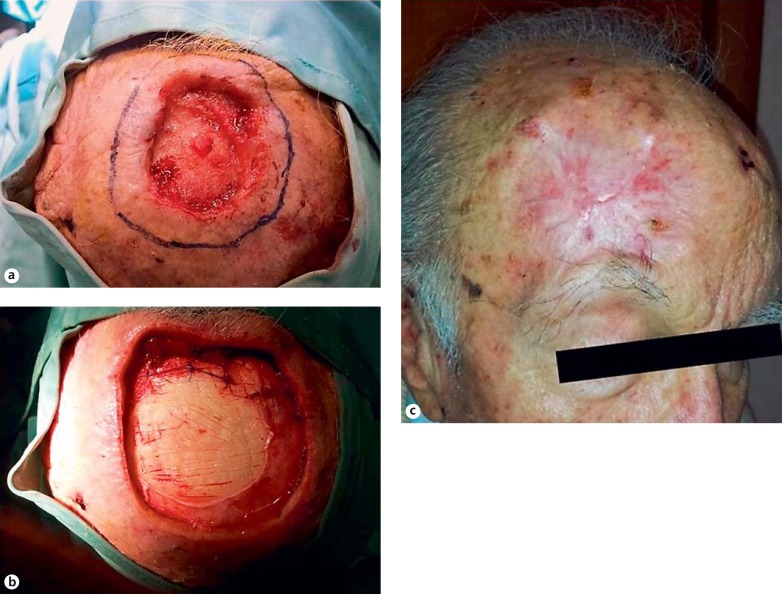

An 84-year-old male patient presented with a large dermal wound in the frontal region, caused by cryosurgery used to treat a basal-cell carcinoma. At the first visit, at the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Second University of Naples, Italy, the skin lesion had resulted in a complete loss of epidermis and dermis, was egg-shaped and with a regular circumference (the lesion size measured 6 × 7 × 1.2 cm, width, length, and depth, respectively; fig. 1a). First, the patient was subjected to the dermal substitute application (Integra®; fig. 1b) which required the surgical extension of the injured area. In June 2013, after the failure of the dermal substitute application, the patient was sent to the Department of Immunohematology and Transfusion Medicine Centre of the Second University of Naples, Italy, for autologous PG topical applications. The skin lesion measured 10 × 12 × 1.2 cm, as reported in table 1. The therapeutic protocol consisted of 4 applications during a period of 3 months with a biweekly frequency. A written informed consent form was obtained from the patient, and treatment was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Fig. 1.

a Dermal wound after cryotherapy. b Dermal wound after dermal substitute application (Integra®). c Complete wound healing (day 90) after treatment with PG.

Table 1.

Autologous PG treatment and follow-up: wound size (cm)

| Days of treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (1st PG appl.) | 14 (2nd PG appl.) | 28 (3rd PG appl.) | 42 (4th PG appl.) | 60 (follow-up) | 90 (follow-up) | |

| Width | 10 | 9.5 | 8 | 7.5 | 4 | 0 |

| Length | 12 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Maximum depth | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 |

The PG was produced using the whole blood separation system Cytomedix Angel® (Gaithersburg, USA), a technology that enables the clinicians to obtain platelet-poor plasma, platelet-rich plasma and red blood cells from anticoagulated whole blood. In our case, we got approximately 4-5 ml of platelet-rich plasma and 6 ml of thrombin from 100 ml (ACD-A anticoagulant included) of blood withdrawn for each treatment.

The PG was applied on days 0, 14, 28, and 42 as shown in table 1. Earlier changes were observed after the first and second applications of autologous PG (days 0 and 14) such as granulation tissue formation, neovascularization, and wound contraction. At the third application (day 28), the granulation tissue formation and the wound contraction were more evident. After the fourth treatment (day 42), the re-epithelialization process was marked. Clinical controls and wound area measurements (width, length, depth, respectively) were performed until the 60th and 90th days of follow-up (table 1). The complete wound healing was observed at the 3-month of follow up (fig. 1c). Overall, the size of the wound area decreased on average by 1.4 cm in width, 1.7 cm in length and 0.7 mm in depth per week.

Discussion

This case showed the clinical efficacy of using PG in an elderly patient to completely heal the loss of epidermis, in whom a dermal substitute graft [7,8] had been ineffective. Prior studies had shown the extensive use of platelet-derived products for clinical and surgical treatments of wound healing [9]. Clinical efficacy, safeness and cost-effectiveness make platelet derivatives a therapeutic option, also for patients whose mechanisms of tissue repair are impaired. The observed regenerative effects of PG could be achieved by autocrine and paracrine substances including growth factors contained mostly in platelet α-granules. Each growth factor could be implicated in a specific phase of the healing process such as inflammation, collagen synthesis, tissue granulation, and angiogenesis which collectively encourage the impaired tissue repair allowing pain relief [10]. In our patient, the PG was found to be an effective therapeutic tool compared with the dermal substitute application which had failed. To our knowledge, there are no comparative studies on the use of PG versus skin grafts in regenerative medicine.

Conclusion

PG treatment produced the complete healing within 90 days by enhancing granulation, tissue formation, neovascularization, and wound contraction. No signs of infection or other side effects were observed. The reported clinical evidence showed that PG was an effective tool available in the management of difficult skin lesions.

Disclosure Statement

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Velnar T, Bailey T, Smrkolj V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1528–1542. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, et al. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picard F, Hersant B, Bosc R, et al. Should we use platelet-rich plasma as an adjunct therapy to treat ‘acute wounds’, ‘burns’, and ‘laser therapies’: a review and a proposal of a quality criteria checklist for further studies. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:163–170. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nurden AT, Nurden P, Sanchez M, et al. Platelets and wound healing. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3532–3548. doi: 10.2741/2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzucco L, Medici D, Serra M, et al. The use of autologous platelet gel to treat difficult-to-heal wounds: a pilot study. Transfusion. 2004;44:1013–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Pascale MR, Sommese L, Casamassimi A, et al. Platelet derivatives in regenerative medicine: an update. Transfus Med Rev. 2015;1:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napoli C, Hayashi T, Cacciatore F, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells as therapeutic agents in the microcirculation: an update. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heiss C, Keymel S, Niesler U, et al. Impaired progenitor cell activity in age-related endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1441–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazakos K, Lyras DN, Verettas D, et al. The use of autologous PRP gel as an aid in the management of acute trauma wounds. Injury. 2009;40:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller JD, Rankin TM, Hua NT, et al. Reduction of pain via platelet-rich plasma in split-thickness skin graft donor sites: a series of matched pairs. Diabet Foot Ankle. 2015;6:24972. doi: 10.3402/dfa.v6.24972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]