Summary

Immune deficiency disorders are a heterogeneous group of diseases of variable genetic aetiology. While the hallmark of immunodeficiency is susceptibility to infection, it is increasingly clear that autoimmunity is prevalent, suggestive of a more general immune dysregulation in some cases. With the increasing use of genetic technologies, the underlying causes of immune dysregulation are beginning to emerge. Here we provide a review of the heterozygous mutations found in the immune checkpoint protein CTLA‐4, identified in cases of common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVID) with accompanying autoimmunity. Study of these mutations provides insights into the biology of CTLA‐4 as well as suggesting approaches for rational treatment of these patients.

Keywords: autoimmunity, co‐stimulation, immunodeficiency diseases, regulatory T cells, T cells

Biology of the CTLA‐4 pathway

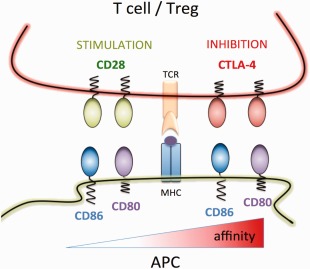

The CTLA‐4 pathway can be thought of as an integrated system involving two opposing receptors CD28 (stimulatory) and CTLA‐4 (inhibitory). CTLA‐4 and CD28 are transmembrane proteins expressed predominantly by T lymphocytes that interact with two shared ligands, CD80 and CD86, found on antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) (Fig. 1). The two ligands differ in both expression pattern and interaction affinities; however, there are still limited data on how they might affect immune function differentially. In line with their relatively small size and their role in regulating T cell responses, both CD28 and CTLA‐4 can be found interacting with their ligands at the immune synapse, where the higher‐affinity CTLA‐4 interactions can compete with CD28 for ligand binding 1, 2.

Figure 1.

Interactions between CD28, CTLA‐4 and their natural ligands. Cartoon shows the immune synapse between a CTLA‐4‐expressing T cell or regulatory T cell (Treg) and an antigen‐presenting cell (APC) expressing the two ligands CD80 and CD86. The affinity of the interactions is depicted from right to left with the lowest interaction CD86–CD28 on the left and the highest CD80–CTLA‐4 on the right.

Whereas CD28 is found at the plasma membrane on T cells, CTLA‐4 expression is more complex. CTLA‐4 is induced following activation of conventional T cells and is expressed constitutively by regulatory T cells (Treg). Approximately 10% of CTLA‐4 is expressed at the plasma membrane at any given time, with 90% occupying a variety of intracellular compartments. This is as a result of CTLA‐4 being internalized via endocytosis, due to the presence of a ‘YVKM’ motif in its cytoplasmic tail 3. This motif interacts constitutively with the clathrin adaptor AP‐2, resulting in rapid internalization of CTLA‐4 in the absence of ligand binding 4. Internalization exposes CTLA‐4 to both recycling and degradation within the cell and it is becoming increasingly clear that correct trafficking is critical to its function.

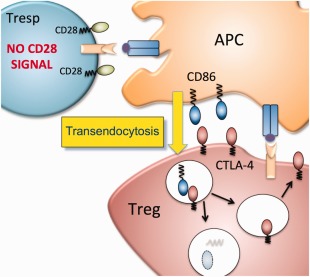

While CTLA‐4 internalization is not well understood, it is nonetheless in keeping with the ability of CTLA‐4 to carry out a process, termed transendocytosis (TE) 5. Here CTLA‐4 binds its ligands at the plasma membrane and subsequently internalizes them, resulting in their removal from the APC. This results in APCs that have impaired expression of ligands and are therefore unable to stimulate T cells through CD28. Such a process potentially explains why CD28 and CTLA‐4 share ligands, and is consistent with a mechanism whereby CTLA‐4 is highly expressed by Treg and can suppress T cell responses in a cell‐extrinsic manner.

In summary, CD28 and CTLA‐4 are functionally opposing receptors expressed by T cells, which interact with the same ligands but with differing affinities and cell biology. These interactions play a central role in balancing both effective immune responses to pathogens as well as regulating autoimmune responses against self‐tissues.

The immunology of CTLA‐4 and CD28

It is increasingly apparent that thymic selection fails to remove all self‐reactive T cells 6, 7, resulting in significant numbers of potentially autoimmune T cells in the circulation of healthy individuals. Not only is the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire highly cross‐reactive, making tolerance by deletion difficult 8, but autoreactive T cells appear to be present at frequencies similar to other antigen specificities 9, arguing that deletion is incomplete. Additional levels of control of T responses (and subsequently B cell responses) to self‐antigens are therefore required, and it is here that the CTLA‐4 receptor is of critical importance 10, 11, 12. It is now established that complete loss of CTLA‐4 in mice causes fatal autoimmunity within ∼3 weeks of birth 13, 14 demonstrating a key, non‐redundant role for CTLA‐4 in preventing autoimmune responses. Furthermore, the description of humans carrying CTLA‐4 mutations and suffering from profound autoimmunity 15, 16 suggests that the autoimmune protective effects of CTLA‐4 are conserved evolutionarily. Similarly, anti‐CTLA‐4 antibodies used to block CTLA‐4 function in the cancer setting can be thought of as treatment‐induced autoimmunity against tumour antigens 17. Taken together, these data argue unequivocally that CTLA‐4 is an essential regulator of immune responses to our own tissues.

In contrast to CTLA‐4, CD28 provides signals that enhance T cell activation and is recognized widely as the archetypal ‘co‐stimulatory’ receptor, alongside the TCR. As CD28 ligands are up‐regulated by inflammatory signals such as those following Toll‐like receptor recognition, CD28 signalling represents ‘danger’ in the context of antigen recognition, driving T cell activation, differentiation and effector function 18. Thus, CD28 engagement by its ligands on APCs is responsive to inflammation, providing a direct connection between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Interestingly, one of the major functions of CD28 co‐stimulation is to facilitate help for B cells via the generation of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells. Accordingly, in the absence of CD28, class‐switched antibody responses are virtually absent 19, germinal centres are impaired 20 and even heterozygous loss at the CD28 locus impacts upon B cell responses 21. A second major feature of the requirement for CD28 co‐stimulation is in the generation and survival of regulatory T cells. Accordingly, in situations where CD28 co‐stimulation is prevented, for example in mice lacking CD28 or its ligands or in the presence of ligand blockade 22, 23, 24, 25, there is an accompanying loss of Treg. Thus, CD28 signalling drives the generation of effector T cell responses, is critical for class‐switched antibody generation and supports homeostasis of Treg, while CTLA‐4 opposes these functions. Together, these features highlight the delicate balance, which is the hallmark of the CD28/CTLA‐4 pathway.

While the co‐stimulatory function of CD28 is relatively clear, the biological function of CTLA‐4 has been more difficult to discern. What is beyond doubt is that CTLA‐4 is a negative regulator of T cell responses. Furthermore, CTLA‐4 is needed to oppose CD28 function, as inhibiting CD28 in mice can prevent disease caused by CTLA‐4 deficiency and, increasingly, such concepts appear to be replicated in humans. Exactly how CTLA‐4 functions at the molecular level remains controversial, with discussion focusing upon cell‐intrinsic (e.g. signalling) versus cell‐extrinsic (e.g. regulatory) mechanisms 10, 11, 12, 26, 27, 28. While it was proposed initially that CTLA‐4 generated inhibitory signals that prevented TCR signalling (cell intrinsic effects), experimental evidence now appears to favour the view that the major CTLA‐4 functions are T cell‐extrinsic and necessary for the effective function of Tregs 29, 30, 31, 32. For example, in mixed bone‐marrow chimeric mice CTLA‐4–/– T cells behave indistinguishably from CTLA‐4+/+ 33, 34, 35, indicating that CTLA‐4+/+ cells can control the behaviour of CTLA‐4–/– T cells extrinsically in a ‘regulatory’ manner. These concepts become significant when it comes to investigating the impact of CTLA‐4 deficiency in patients and how to determine defective CTLA‐4 function.

The idea that CTLA‐4 on T cells acts extrinsically to regulate the behaviour of other T cells is in keeping with the TE model of CTLA‐4 function. Here CTLA‐4 acts as a competitor for CD28 stimulation by removing their shared ligands physically from APCs 5 (Fig. 2), consistent with CTLA‐4 as an effector mechanism for Treg suppressive activity. However, a number of other models have also been proposed, including inhibitory signalling, triggering of tryptophan metabolism and effects on T cell motility (see 11, 26, 27, 28 for reviews). Currently, the actual mechanisms critical to CTLA‐4 function in vivo remain to be established formally.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action for CTLA‐4. A regulatory T cell (Treg)‐expressing CTLA‐4 can capture and internalize stimulatory ligands (CD86 shown) by transendocytosis. Ligands are internalized into the CTLA‐4‐expressing cell and degraded while CTLA‐4 is recycled. This results in reduction of available CD86 and therefore loss of CD28 co‐stimulatory signals in the responder T cell (Tresp). This mechanism is compatible with much of the biology of CTLA‐4, but is not exclusive of other mechanisms.

Identification of CTLA‐4 deficiency and clinical features

Overactivity of the immune system resulting in autoimmune and inflammatory complications is a well‐recognized paradox in primary immunodeficiency (PID) disorders 36. For example, in addition to antibody deficiency, a spectrum of immune dysregulation is seen in common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVID) which includes, but is by no means limited to, B cell and autoantibody‐mediated conditions. Lymphocytic infiltration and granuloma formation, particularly involving gut, lung and liver, are hallmarks of such associated immune dysregulation and likely to involve multiple immune lineages. Recently, loss of function mutations in CTLA‐4 have emerged, mainly from cohorts of patients diagnosed with antibody deficiency and severe immune dysregulation 15, 16, providing insight into the pathogenesis of immune dysregulation in a subset of patients.

Schubert et al. investigated a large kindred with five family members affected by hypogammaglobulinaemia, recurrent respiratory tract infections, autoimmune cytopenia, autoimmune enteropathy and infiltrative lung disease (who were found to have heterozygous mutations in CTLA‐4 15). Genetic analysis revealed the same CTLA‐4 mutation in six other family members considered to be healthy. Based on clinical phenotype, other families with CVID and enteropathy or autoimmunity were investigated, revealing five additional index patients with novel CTLA‐4 mutations, three asymptomatic mutation ‘carriers’ and a further four patients based on family history.

Another study 16 reported nine patients with CTLA‐4 mutations in four unrelated families with a history of hypogammaglobulinaemia, CD4+ T cell lymphopenia, autoimmune cytopenias and lymphocytic infiltration. Of these, six individuals were clinically symptomatic, with three reportedly healthy. Additional sporadic cases have been reported 37, 38, 39, 40 and a further eight patients with CTLA‐4 mutations who underwent stem cell transplantation have also been described 41. Similar clinical features were reported in most cases, as well as additional complications that extend the spectrum of disease including autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, pure red cell aplasia, adrenal insufficiency, type I diabetes, arthritis and autoimmune choirodopathy.

The reported clinical features of CTLA‐4 deficiency described to date are summarized in Table 1. With the exception of recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections, almost all relate to immune dysregulation and autoimmunity. Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy are common and extensive CD4+ T cell organ infiltration can be seen in multiple organs, including the intestine, lung, bone marrow, central nervous system and kidney. Although opportunistic infections do not appear to be a prominent feature, one patient was diagnosed with cytomegalovirus (CMV) gastritis prior to development of gastric carcinoma 39, albeit following steroid treatment. Malignancy risk appears to be elevated, with three patients developing gastric carcinoma and two Hodgkin's lymphoma. It is not yet known if currently classified asymptomatic/healthy patients will progress at a later stage, and this will be an important question for follow‐up studies.

Table 1.

Main clinical features associated with confirmed cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) mutations

| Lung |

| Granulomatous lymphocytic interstital lung disease (infiltrative lung disease) |

| Fibrosis |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Cytopenias |

| Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia |

| Autoimmune thrombocytopenia |

| Autoimmune neutropenia |

| Gut |

| Diarrhoea/enteropathy |

| Gastric cancer |

| Autoimmunity |

| Type 1 diabetes |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis |

| Arthritis |

| Psoriasis |

| Uveitis |

| Vitiligo |

| Myasthenia gravis |

| Others |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| Splenomegaly |

| Lymphocytic infiltration of non‐lymphoid organs (lung, bone marrow, gut, brain) |

| Malignancy |

Reduced immunoglobulin levels were noted in most symptomatic patients with heterozygous CTLA‐4 mutations 15, 16. In the majority of individuals this was associated with a low or progressively falling percentage of CD19+ B cells, a low percentage of switched‐memory B cells and a predominance of CD21low B cells, which are thought to represent exhausted B cells producing lower levels of immunoglobulin in vitro. In addition, there is evidence of excessive T cell activation indicated by low levels of naive T cells and elevated expression of the surface molecule programmed cell death protein 1 (PD‐1). Forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) regulatory T cells are present at normal or even higher percentages, but these express low levels of CTLA‐4 and function poorly 42. Conventional T cell proliferation and in‐vitro T cell differentiation are preserved.

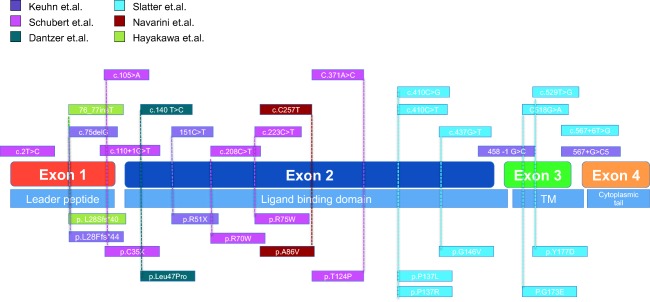

The majority of mutations in CTLA‐4 affect the CTLA‐4 extracellular domain (Fig. 3). However, there does not appear to be a clear genotype–phenotype correlation and incomplete clinical penetrance has not been explained fully. Additional factors, including genetic and epigenetic modifiers, microbial exposure or environmental factors, may therefore influence the clinical outcome of CTLA‐4 deficiency. It is interesting to note that bi‐allelic loss of function mutations in lipopolysaccharide responsive beige‐like anchor protein (LRBA) result in a phenocopy disease with autosomal recessive inheritance and severe early onset 43. It is now known that CTLA‐4 requires LRBA for regulation of its intracellular trafficking, so that loss of LRBA expression effectively reduces CTLA‐4 expression, resulting in functional CTLA‐4 deficiency 44.

Figure 3.

Schematic view of reported cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) mutations. DNA mutations are shown in the upper half of the diagram and aligned with amino acid changes below. The alignment between exons and protein functional domains is shown. Mutations are colour‐coded according to the report in which they are described.

Lessons from CTLA‐4 deficiency in humans

The fact that CTLA‐4 deficiency results in highly variable features of autoimmunity appears to result from inappropriate activation of polyclonal T cells. This may be observed clinically, in that these patients generally have expanded populations of memory T cells. Thus, while presentation of disease is highly variable, it is consistent with the concept of increased CD28 co‐stimulation triggering self‐reactive T cells against a variety of tissues. Similarly, in CTLA‐4‐deficient mice, T cells are seen to infiltrate multiple tissues and to recognize autoantigens 13, 14, 45. It may be significant that many of the sites worst affected, e.g. gut, lungs and skin, are also sites where there is an interface with the microbiome, where the levels of co‐stimulatory molecules on APCs may be higher.

A key feature of CTLA‐4 deficiency in humans is the impact on the Treg cell compartment. Consistent with a T cell‐extrinsic role for CTLA‐4, a Treg functional deficiency is observed in these patients, with an impaired ability to suppress T cell proliferation 15, 16. This defect relates to impaired CTLA‐4 function, as suppression in these experiments is abrogated by anti‐CTLA‐4 antibody 15. In addition, the impaired ability of Treg from CTLA‐4 mutation carriers (both clinically affected and unaffected) to carry out transendocytosis or to uptake soluble CTLA‐4 ligands was also observed 42. As Treg express the highest levels of CTLA‐4, it may be that deficiency in one allele is sufficient to compromise the high levels of expression required for effective function.

Given the role of CD28 in Treg homeostasis 24, 25, 46, it might be expected that Treg proportions are affected in CTLA‐4 deficiency. Mice deficient in CTLA‐4 show marked expansions in Treg numbers due to the increased availability of CD28 signalling 47 and similar expansions are seen in a number of CTLA‐4 deficient patients. It should be noted that Treg analysis is frequently confounded by the low expression of CD25, which is seen in many CVID patients, and precludes the use of CD25 as a marker for Treg. However, we have observed that FoxP3 staining, particularly following a brief stimulation, reveals that Treg numbers are generally normal or elevated in these patients, with some individuals displaying very marked expansions 42.

While the impact of CTLA‐4 deficiency on Treg biology is clear, its effects on activated T cells, which also express CTLA‐4, are more difficult to determine. It has been suggested that conventional CD4 and CD8 T cells in individuals with CTLA‐4 mutations can be hyperproliferative 16, 38, 48. However, this has not been our experience, and such experiments require careful set‐up and interpretation. We have shown previously that CTLA‐4 plays little if any intrinsic role in regulating the proliferation of human CD4 T cells 49, nor is CTLA‐4 function measured readily in assays where CD3/CD28 antibodies are used as a stimulus. Given that patients with CTLA‐4 deficiency often have a preponderance of activated and memory T cells in their blood, direct comparisons with control samples are confounded unless this is corrected for. Thus, further studies are needed and it is not yet clear that in‐vitro hyperproliferation of conventional T cells is a direct consequence or a useful measure of CTLA‐4 deficiency.

Treatment options for CTLA‐4 deficiency

Management of patients with CTLA‐4 deficiency requires attention to both the immunodeficiency and immune dysregulation features of disease. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy, with or without prophylactic antibiotics, represents the main conservative management approach for infection prophylaxis. However, given that CTLA‐4 deficiency is in essence a T cell hyperactivation disorder, immunosuppressive compounds are frequently required, despite the potential for worsening immunodeficiency. Given the rare nature of the condition, there are no agreed treatment guidelines for managing the associated immune dysregulation and very little evidence for long‐term response to different immunosuppressive agents that could be used to rationalize drug selection.

In CTLA‐4 deficiency, limited information from case reports indicates that that corticosteroids have been the most consistently utilized immunosuppressive for autoimmune cytopoenias, enteropathy, infiltrative lung disease and central nervous system (CNS) inflammation 15, 16. Reported responses are variable and the need for high‐dose and recurrent doses of steroids is apparent. A number of steroid‐sparing agents have also been employed, including sirolimus in multiple patients, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclosporin A, anti‐thymocyte globulin, anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) drugs and vedoluzimab, with improvement in some, but not all, cases 15, 16, 37, 38. Even for individual patients, some features of immune dysregulation may respond to a given drug while other complications remain resistant. The need for recurrent, multiple and serial steroid‐sparing agents in CTLA‐4 deficiency highlights the severity of immunopathology in this condition, as well as the inadequacy of current treatment approaches.

Abatacept, a CTLA‐4–immunoglobulin fusion protein licensed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis 50, holds promise as a more rational and targeted approach to treatment. As abatacept is a soluble version of CTLA‐4 itself it may be considered as a CTLA‐4 replacement therapy. Additional experience has been published for use of abatacept to treat infiltrative lung disease in LRBA deficiency with an improvement in the clinical status, high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest radiological appearances and pulmonary function tests in three patients using a dosing regimen of 20 mg/kg every 2–4 weeks for up to 8 years 44. Chronic norovirus was observed in two of the patients, but otherwise there were minimal infections with no deterioration in lung disease while on treatment. In this study, an additional three patients commenced abatacept for gastrointestinal disease with reported improvement in two of three of the patients during a short follow‐up of less than 6 months on treatment, with up to 30 mg/kg dosing 2‐weekly. To date, there are only two instructive published reports of abatacept use in CTLA‐4 deficiency. In one case, an unspecified dose of abatacept was used for autoimmune choroidopathy with good response within 3 months 40. In the second case, treatment was instigated for enteropathy and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (dose 10 mg/kg 2‐weekly), with good response and no reported side effects 48. In addition, sustained remission throughout several months was achieved with a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg monthly. It is still not clear whether abatacept is sufficient as a sole long‐term immunosuppressive agent for patients with CTLA‐4 deficiency, and future trials should also consider belatacept, which is a similar molecule with a higher ligand affinity, currently in trial for prevention of renal transplant rejection (https://clinicaltrials.gov).

Haematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been used as a treatment strategy for life‐threatening, treatment‐resistant immune dysregulation in CTLA‐4 deficiency 41. Eight patients with severe clinical disease were transplanted with an age range of 10–32 years. Six were alive and well in April 2016 (3·5 months, 4 months, 2 years, 4 years, 4·75 years and 10·2 years post‐transplant, respectively), one with ongoing sirolimus for resolving chronic GVHD. In total, GHVD was seen in four patients, and led to death in one case. A second patient died 2·5 years post‐transplant from diabetic ketoacidosis. These results are encouraging, and demonstrate that CTLA‐4 deficiency can potentially be cured by HSCT, although GVHD risk may be higher because of the inflammatory burden at transplantation making autologous gene therapy approaches an attractive proposition for the future.

Conclusions

CTLA‐4 deficiency is a novel PID that joins the growing subset of inherited immunodeficiencies associated with prominent autoimmunity and immune dysregulation. It is evident that Treg dysfunction is a key mechanism of the immune activation associated with CTLA‐4 loss of function mutations, although the cellular causes of immunodeficiency remain unclear. The availability of pathway‐specific treatments that provide a soluble form of CTLA‐4 hold promise for targeted therapy and highlight the importance of gene discovery to improve treatment for PID presenting outside, as well as during, childhood. Finally, lessons learnt from CTLA‐4 in PID have application for other common autoimmune diseases and potentially cancer immunotherapy.

Disclosure

The authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1. Egen JG, Allison JP. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 accumulation in the immunological synapse is regulated by TCR signal strength. Immunity 2002; 16:23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yokosuka T, Kobayashi W, Takamatsu M et al Spatiotemporal basis of CTLA‐4 costimulatory molecule‐mediated negative regulation of T cell activation. Immunity 2010; 33:326–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shiratori T, Miyatake S, Ohno H et al Tyrosine phosphorylation controls internalization of CTLA‐4 by regulating its interaction with clathrin‐associated adaptor complex AP‐2. Immunity 1997; 6:583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qureshi OS, Kaur S, Hou TZ et al Constitutive clathrin‐mediated endocytosis of CTLA‐4 persists during T cell activation. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:9429–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K et al Trans‐endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell‐extrinsic function of CTLA‐4. Science 2011; 332:600–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malhotra D, Linehan JL, Dileepan T et al Tolerance is established in polyclonal CD4(+) T cells by distinct mechanisms, according to self‐peptide expression patterns. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. The self‐obsession of T cells: how TCR signaling thresholds affect fate ‘decisions’ and effector function. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:815–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sewell AK. Why must T cells be cross‐reactive? Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:669–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Su LF, Kidd BA, Han A, Kotzin JJ, Davis MM. Virus‐specific CD4(+) memory‐phenotype T cells are abundant in unexposed adults. Immunity 2013; 38:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walker LS, Sansom DM. The emerging role of CTLA4 as a cell‐extrinsic regulator of T cell responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:852–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walker LS, Sansom DM. Confusing signals: recent progress in CTLA‐4 biology. Trends Immunol 2015; 36:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schildberg FA, Klein SR, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory pathways in the B7‐CD28 ligand‐receptor family. Immunity 2016; 44:955–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E et al Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in CTLA‐4. Science 1995; 270:985–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA‐4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA‐4. Immunity 1995; 3:541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schubert D, Bode C, Kenefeck R et al Autosomal dominant immune dysregulation syndrome in humans with CTLA4 mutations. Nat Med 2014; 20:1410–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuehn HS, Ouyang W, Lo B et al Immune dysregulation in human subjects with heterozygous germline mutations in CTLA4. Science 2014; 345:1623–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015; 348:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soskic B, Qureshi OS, Hou T, Sansom DM. A transendocytosis perspective on the CD28/CTLA‐4 pathway. Adv Immunol 2014; 124:95–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shahinian A, Pfeffer K, Lee KP et al Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28 deficient mice. Science 1993; 261:609–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walker LS, Gulbranson‐Judge A, Flynn S et al Compromised OX40 function in CD28‐deficient mice is linked with failure to develop CXC chemokine receptor 5‐positive CD4 cells and germinal centers. J Exp Med 1999; 190:1115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang CJ, Heuts F, Ovcinnikovs V et al CTLA‐4 controls follicular helper T‐cell differentiation by regulating the strength of CD28 engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:524–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L et al B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity 2000; 12:431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bar‐On L, Birnberg T, Kim KW, Jung S. Dendritic cell‐restricted CD80/86 deficiency results in peripheral regulatory T‐cell reduction but is not associated with lymphocyte hyperactivation. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41:291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gogishvili T, Luhder F, Goebbels S, Beer‐Hammer S, Pfeffer K, Hunig T. Cell‐intrinsic and ‐extrinsic control of Treg‐cell homeostasis and function revealed by induced CD28 deletion. Eur J Immunol 2013; 43:188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Boden EK et al Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2003; 171:3348–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rudd CE, Taylor A, Schneider H. CD28 and CTLA‐4 coreceptor expression and signal transduction. Immunol Rev 2009; 229:12–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wing K, Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Cell‐autonomous and ‐non‐autonomous roles of CTLA‐4 in immune regulation. Trends Immunol 2011; 32:428–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bour‐Jordan H, Esensten JH, Martinez‐Llordella M, Penaranda C, Stumpf M, Bluestone JA. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of peripheral T‐cell tolerance by costimulatory molecules of the CD28/B7 family. Immunol Rev 2011; 241:180–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto‐Martin P et al CTLA‐4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science 2008; 322:271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Friedline RH, Brown DS, Nguyen H et al CD4+ regulatory T cells require CTLA‐4 for the maintenance of systemic tolerance. J Exp Med 2009; 206:421–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med 2000; 192:295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S et al Immunologic self‐tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4. J Exp Med 2000; 192:303–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bachmann MF, Kohler G, Ecabert B, Mak TW, Kopf M. Cutting edge: lymphoproliferative disease in the absence of CTLA‐4 is not T cell autonomous. J Immunol 1999; 163:1128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bachmann MF, Gallimore A, Jones E, Ecabert B, Acha‐Orbea H, Kopf M. Normal pathogen‐specific immune responses mounted by CTLA‐4‐deficient T cells: a paradigm reconsidered. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31:450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Homann D, Dummer W, Wolfe T et al Lack of intrinsic CTLA‐4 expression has minimal effect on regulation of antiviral T‐cell immunity. J Virol 2006; 80:270–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gathmann B, Mahlaoui N, Ceredih G et al Clinical picture and treatment of 2212 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Navarini AA, Hruz P, Berger CT et al Vedolizumab as a successful treatment of CTLA‐4‐associated autoimmune enterocolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:1043–6 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zeissig S, Petersen BS, Tomczak M et al Early‐onset Crohn's disease and autoimmunity associated with a variant in CTLA‐4. Gut 2015; 64:1889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayakawa S, Okada S, Tsumura M et al A patient with CTLA‐4 haploinsufficiency presenting gastric cancer. J Clin Immunol 2016; 36:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shields CL, Say EA, Mashayekhi A, Garg SJ, Dunn JP, Shields JA. Assessment of CTLA‐4 deficiency‐related autoimmune choroidopathy response to abatacept. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134:844–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Slatter MA, Engelhardt KR, Burroughs LM et al Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for CTLA4 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:615–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hou TZ, Verma N, Wanders J et al Identifying functional defects in patients with immune dysregulation due to LRBA and CTLA‐4 mutations. Blood 2017; 129:1458–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lopez‐Herrera G, Tampella G, Pan‐Hammarstrom Q et al Deleterious mutations in LRBA are associated with a syndrome of immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90:986–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W et al Patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science 2015; 349:436–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ise W, Kohyama M, Nutsch KM et al CTLA‐4 suppresses the pathogenicity of self antigen‐specific T cells by cell‐intrinsic and cell‐extrinsic mechanisms. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:129–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang R, Huynh A, Whitcher G, Chang J, Maltzman JS, Turka LA. An obligate cell‐intrinsic function for CD28 in Tregs. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:580–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schmidt EM, Wang CJ, Ryan GA et al Ctla‐4 controls regulatory T cell peripheral homeostasis and is required for suppression of pancreatic islet autoimmunity. J Immunol 2009; 182:274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee S, Moon JS, Lee CR et al Abatacept alleviates severe autoimmune symptoms in a patient carrying a de novo variant in CTLA‐4. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hou TZ, Qureshi O, Wang CJ et al A Transendocytosis model of CTLA‐4 function predicts its suppressive behaviour on regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2015; 194:2148–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chitale S, Moots R. Abatacept: the first T lymphocyte co‐stimulation modulator, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2008; 8:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]