Abstract

Active sites and ligand binding cavities in native proteins are often formed by curved β-sheets, and the ability to control β-sheet curvature would allow design of binding proteins with cavities customized to specific ligands. Towards this end, we investigated the mechanisms controlling β-sheet curvature by studying the geometry of β-sheets in naturally occurring protein structures and folding simulations. The principles emerging from this analysis were used to de novo design a series of proteins with curved β-sheets topped with a-helices. NMR and crystal structures of the designs closely match the computational models, showing that β-sheet curvature can be controlled with atomic-level accuracy. Our approach enables the design of proteins with cavities and provides a route to custom design ligand binding and catalytic sites.

Ligand binding proteins with curved β-sheets surrounding the binding pocket, as in the NTF2-like, β-barrel, and jelly roll folds, play key roles in molecular recognition, metabolic pathways and cell signaling. Approaches to designing small molecule binding proteins and enzymes to date have started by searching for native protein scaffolds with ligand binding pockets with roughly the right geometry, and then redesigning the surrounding residues to optimize interactions with the small molecule. While this approach has yielded new binding proteins and catalysts (1–5), it is not optimal: there may be no naturally occurring scaffold with a pocket with the correct geometry, and introduction of mutations in the design process may change the pocket structure (6, 7). Building de novo proteins with custom-tailored binding sites could be a more effective strategy, but this remains an outstanding challenge (8–11). De novo protein design has recently focused on proteins with ideal backbone structures (12–16) (straight helices, uniform β-strands and short loops; see ref (17) for a recent exception) and optimal core sidechain packing, but the binding pockets of naturally occurring proteins lie on concave surfaces formed by non-ideal features such as kinked helices, curved β-sheets or long loops. The design of proteins with concave surfaces requires examination of how such irregular structural features can be programmed into the amino acid sequence.

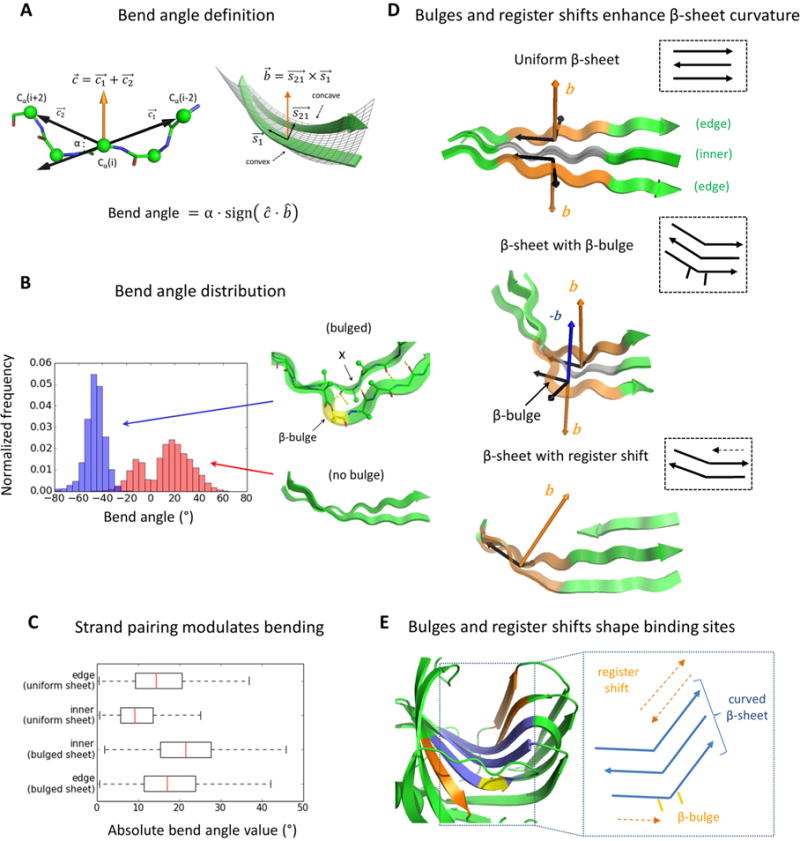

We begin by analyzing how classic (18, 19) β-bulges (irregularities in the pleating of edge strands) and register shifts (local termination of strand pairing) coupled with intrinsic β-strand geometry induce curvature in antiparallel β-sheets (20, 21). We quantify the curvature of an edge strand making an antiparallel pairing with a second strand by the bend angle (Fig. 1A). The absolute value of the bend angle (α) at residue i is the angle between vectors from the Cα(i) atom to Cα(i−2) and Cα(i+2). The bend angle sign is a function of the relative orientation of a vector describing the concave face of the edge strand (Fig. 1A, left), a vector between the edge strand and the second strand (Fig. 1 A, right), and a vector along the edge strand direction (Fig. 1A, right). We analyzed the bend angle of two-stranded antiparallel β-sheets in naturally occurring protein structures and in Rosetta folding simulations (Fig. 1B and fig. S1), and found that uniform strands tend to have positive bend angles (due to steric interactions between paired β-strands, fig. S2), while strands containing β-bulges tend to have negative bend angles (due to the different hydrogen bond pairing of β-bulges; Fig. 1B and figs. S2 and S3). For β-sheets of three strands or more, we found that the type of strand pairing determines the magnitude of β-sheet curvature (Fig. 1C). In uniform 3-stranded antiparallel β-sheets, the bend directions of the two edge strand segments point in opposite directions, constraining the bend angle of the inner strand to close to zero and flattening the β-sheet (Fig. 1D, top). In contrast, in 3-stranded β-sheets with a β-bulge in one of the edge strands, the two edge strand segments bend in the same direction, leading to increased overall bending of the β-sheet (Fig. 1D, middle). In uniform β-sheets, register shifts enhance bending by terminating pairing between strand segments that would otherwise have opposite bending directions and flatten the β-sheet. (Fig. 1D, bottom). β-sheet curvature can hence be programmed by combining β-bulges and register shifts. For example, a number of naturally occurring proteins contain a three-strand β-sheet core with β-bulge derived curvature complemented by additional strands with register shifts propagating the curvature (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. Rules for β-sheet curvature design.

A) Bend angle definition. (B) Distribution of bend angles for strand pairs formed by uniform (red) and bulged (blue) strands. The local hydrogen bonding and offset in sidechain directionality at the β-bulge position are shown. The bulge and the residue following donate two backbone hydrogen bonds to the same residue X. (C) Bend angle (absolute value) box plots of strands with different pairing types in native 3-stranded β-sheets. The edge strand distribution in the bulged β-sheet case (bottom) is for the strand that does not contain the bulge. (D) Representation of the vector in edge strand pairs for three types of 3-stranded β-sheets. β-sheet with β-bulge (middle) shows the - vector for the bulged strand pair to indicate the natural bend direction resulting from a negative bend angle. (E) On the left, cartoon representation of the binding site formed by a curved β-sheet in a native xylanase (PDB entry 2B45). The curved 3-stranded β-sheet core is shown in blue, the β-bulge in yellow and the extra strands in orange. On the right, schematic representation of strand pairings in the curved β-sheet formed by a β-bulge and register shift.

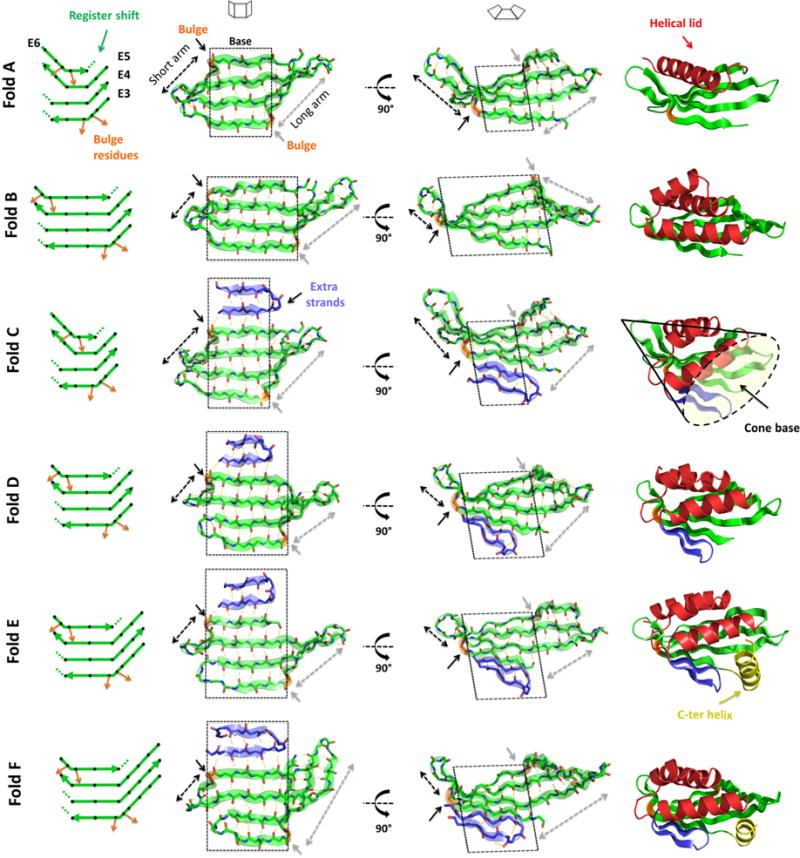

Using these relationships between β-bulges, register shifts and the direction and magnitude of β-sheet curvature, we designed six protein folds (labeled from A to F, Fig. 2) inspired by the naturally occurring cystatin and NTF2-like superfamilies with a 4-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, β-bulges at the edge strands and strand lengths ranging between 10 and 14 residues. The width of the β-sheet central base (along the strand direction) is controlled by the relative position between β-bulges (folds A, D and B have central bases of increasing width), while the depth (perpendicular to the strand direction) is controlled by the number of strand pairs (folds C, D, E and F increase the depth of folds A and B by adding on two extra strands; Fig. 2). The lengths of the two arms flanking the relatively flat center of the base are controlled by the strand lengths and β-bulge positions (folds D, E and F have arms of increasing length). We complemented the β-sheets with one (fold A), three (folds B, C and D) or four (folds E and F) α-helices to form overall cone-shaped structures (Fig. 2; folds B, C and D have wide cone bases, while fold E partially occludes the cone base with the fourth helix), which provide starting points for designing small molecule binding sites with entrances at the base of the cone.

Fig. 2. Designed β-sheets and folds.

On the left, diagrams of the 4-stranded antiparallel β-sheets. Black diamonds represent residues with sidechains pointing to the convex face of the β-sheet and orange arrows highlight the β-bulge offset in sidechain directionality. Dotted lines show the local termination of strand pairing due to register shift between paired strands. Second and third columns show two views of the designed β-sheets. Black and gray dashed arrows show the length of the short and long arms, respectively, that emerge from the flat central base (highlighted by a black dashed square). On the right, examples of each designed protein fold containing 4-stranded antiparallel β-sheets (green), helical lids (red), extra strands (blue) and a C-terminal helix capping the pocket entrance (yellow). The concave base of these conical folds is well suited for small molecule binding site design.

We constructed the protein backbones with a stepwise Monte Carlo fragment assembly protocol (22) that sequentially adds elements of secondary structure (strands and helices), β-bulges and loops (23). Hairpins were designed with two-residue loops following the ββ-rule (12), which requires β-bulges to be at even and odd positions from the following and previous hairpin loops, respectively (due to the offset in sidechain directionality of β-bulges, fig. S3). We then carried out RosettaDesign calculations (24) to favor amino acid identities and sidechain conformations with low-energy, tight packing and high sequence-structure compatibility. We hypothesized that β-bulge positions could be specified at the sequence level solely by changing the normal alternating pattern of polar and hydrophobic amino acids (more complex patterns are observed in native structures (see refs (19, 25) and fig. S4)) — in a β-bulge, unlike regular strands, two successive residues point in the same direction (Fig. 1B). We relied on sidechain packing to drive strand bending in strands without β-bulges (see ref (26) and fig. S5). Loops were designed with sequence profiles obtained from protein fragments with similar backbone torsion angles (23). We characterized the folding energy landscape of the designs by Rosetta ab initio structure prediction calculations (27, 28) preceded by a fast initial screen to eliminate designs incapable of folding even with local bias towards the native structure (23). We chose for experimental characterization designs with funnel-shaped energy landscapes ranging between 74 and 120 amino acids (table S1) (design names are dcs_X_n; where “dcs” stands for designed curved β-sheet, “X” the fold type and “n” the design number; and a “_ss” suffix if disulfide bonds are present). Blast searches (29, 30) indicated that the designed sequences had weak or no similarity with native proteins (E-values ranging from 0.00002, for two of the nine fold D designs, to > 10; table S2); TM-align searches (31) identified structures with global fold similarity, but little sequence similarity (E-values > 10, except for the two designs of fold D with low E-value, where the top Blast hit was reidentified) and differences in the relative orientation of secondary structure elements and loop connections (fig. S6).

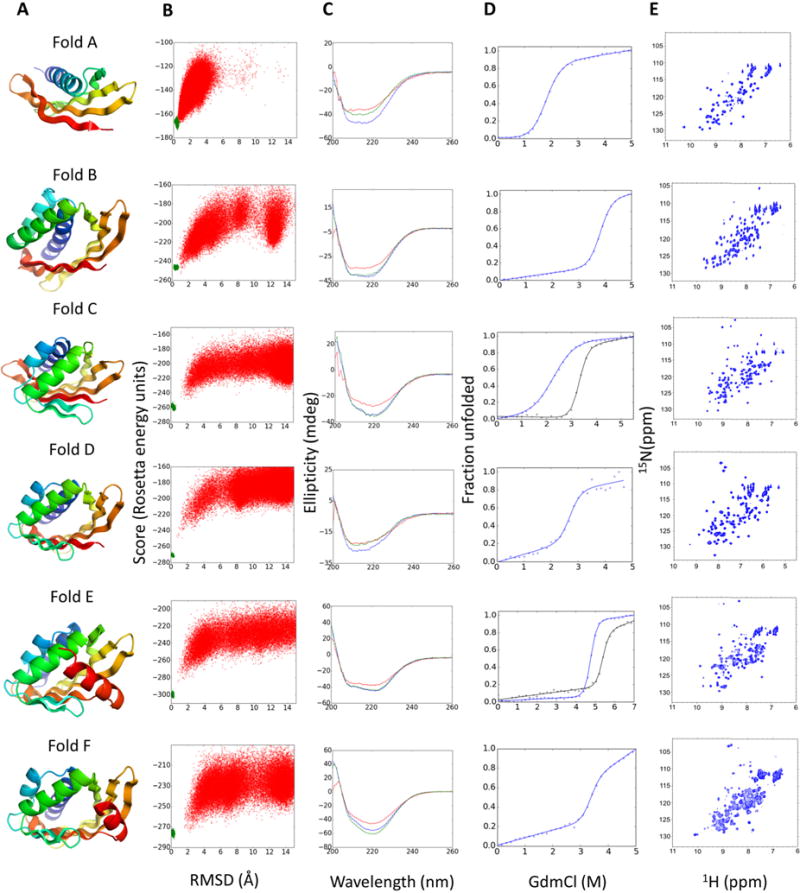

We obtained synthetic genes encoding 37 designs, expressed the proteins in Escherichia coli and purified them by affinity chromatography. Thirty-three of the designs had far-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectra (CD) at 25 °C characteristic of α,β proteins, and were monomeric by size-exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS; Fig. 3, figs. S7 to S12 and table S1). Thirty-one of the designs have a melting temperature (Tm) above 95 °C and 24 unfold cooperatively in guanidium chloride (GdmCl). Two-dimensional 1H–15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra suggest that twelve designs fold into well-ordered structures. Fold E designs, which have a long C-terminal helix as a lid capping the cone base, were the most stable (with Tm > 95 °C and denaturation midpoints up to 6M GdmCl at 25 °C; fig. S11 and table S3). Fold F designs also were thermostable, but their non-cooperative unfolding and poor HSQC spectra (fig. S12) suggest imperfect design of the short C-terminal helix interaction with the long arm.

Fig. 3. Experimental characterization of designed proteins for each fold.

(A) Examples of design models for each fold. (B) Folding energy landscapes generated by ab initio structure prediction calculations. Each dot represents the lowest energy structure identified in an independent trajectory starting from an extended chain (red dots) or from the design model (green dots); x-axis shows the Cα-root mean squared deviation (RMSD) from the designed model; the y-axis shows the Rosetta all-atom energy. (C) Far-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectra (blue: 25 °C, red: 95 °C, green: 25 °C after cooling). (D) Chemical denaturation with GdmCl monitored with circular dichroism at 220 nm and 25 °C. For folds C and D the denaturation curves for designs stabilized by a disulfide bond or a dimer interface are shown in black lines. (E) 1H–15N HSQC spectra obtained at 25 °C.

We reasoned that when designing function into these de novo scaffolds, the proximity between the active site and the protein core could compromise protein stability, and explored two additional stabilization strategies that would preserve pocket accessibility: disulfide bonds and homodimer design. We designed disulfide bonds in positions peripheral to the cone base of folds C and D (23). For six of eight designs characterized, disulfide bonds enhanced protein expression, folding cooperativity and stability by up to 8 kcal·mol−1 (fig. S13 and table S3). We designed homodimers of fold E designs with shape complementary low energy interfaces formed by the convex face of the curved β-sheet (23). Nine designs with deep global energy minima at the designed dimer configuration in docking calculations were selected for experimental characterization and three were found to form soluble dimers; the best expressed design (dcs_E_4_dim9) is 1.4 kcal·mol−1 more stable than the original monomer (fig. S14).

High resolution structural analysis is essential for evaluation of the accuracy of computational designs and quickly becomes the bottleneck in protein design studies. During the course of our efforts to solve structures of the designs, we found that the cooperativity of chemical denaturation with GdmCl was a better predictor of rigid core formation, as indicated by NMR HSQC spectra or the ability to crystallize, than was thermostability (fig. S15)—a number of thermostable designs had molten globule-like sidechain packing. This relationship allows the focusing of structure characterization on the designs with the best defined structures.

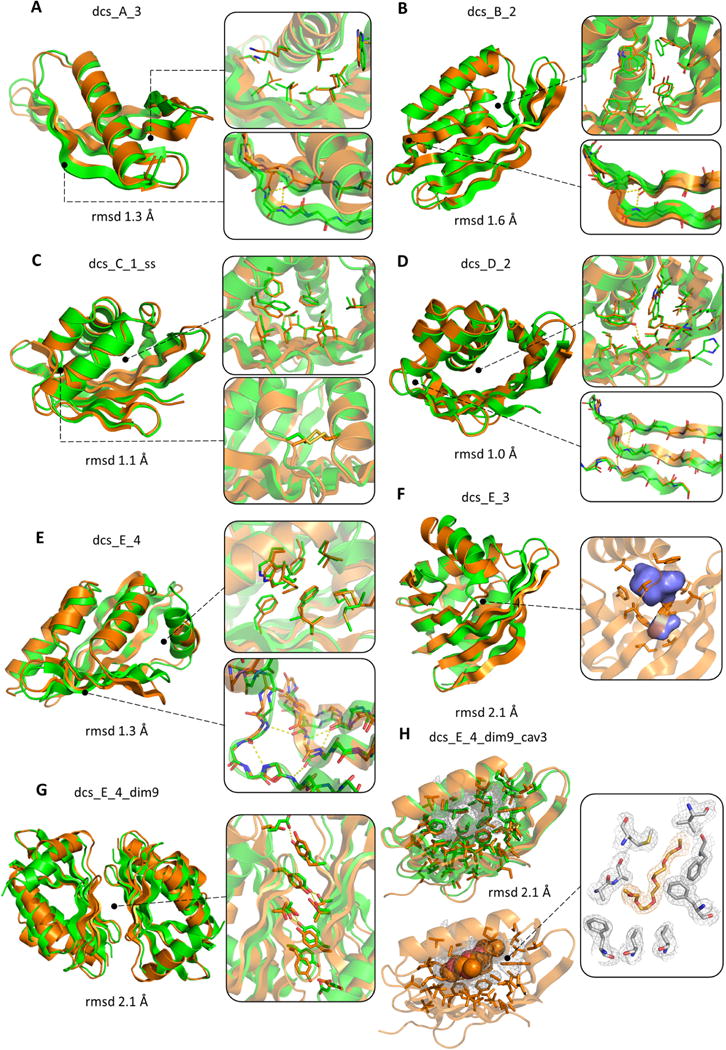

We solved the structures of nine designs by NMR spectroscopy or X-ray crystallography. These experimental structures span five different folds (from A to E) (Fig. 4) and are in close agreement with the computational models (Cα-RMSDs from 1.0 to 2.1 Å). The overall β-sheet curvatures were accurately recapitulated and β-bulge positions were as predicted, supporting our hypothesis about local encoding of β-bulges. Crystal contacts in the structures of dcs_C_1_ss, dcs_D_2, dcs_E_3, dcs_E_4 and dcs_A_4 support the idea that β-bulges minimize edge-to-edge strand pairing (32): hydrogen bond pairing is restricted to the regular strand segments (fig. S16).

Fig. 4. Experimentally determined structures of designed proteins.

In each panel the experimental structure and the design model are superimposed and colored in orange and green, respectively. Insets show comparisons of sidechain rotamers, β-bulge geometry and cavities; and designed sidechain and β-bulge hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow dashed lines. The RMSD calculated over all Ca atoms is shown in each panel. (A) dcs_A_3 and (B) dcs_B_2 were solved by NMR (comparisons utilized the lowest energy NMR model). (C) dcs_C_1_ss (3.0 Å resolution) with designed disulfide bond in inset. (D) dcs_D_2 (2.0 Å resolution). (E) dcs_E_4 (2.9 Å resolution). (F) dcs_E_3 (3.1 Å resolution); an internal hydrophobic cavity forms in both the design and the crystal structure (volume 192 Å3). (G) dcs_E_4_dim9 (2.4 Å resolution); the interface aromatic stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions are very similar in the crystal structure and design model (right inset). (H) dcs_E_4_dim9_cav3 (1.8 Å resolution). A large (520 Å3) cavity is filled with a pentaethylene glycol molecule in the crystal structure (bottom left; electron density map is on right and design model on upper left). The C-terminal helix and the dimer interface are not shown for better visualization of the cavity.

The experimental structures for folds A (dcs_A_3 by NMR, Fig. 4A; and dcs_A_4 by X-ray crystallography, fig. S17) and B (dcs_B_2 by NMR; Fig. 4B) are in close agreement with the design models in the core of the β-sheet and the helices. The designed sidechain packing between the tips of the two β-sheet arms and the helix was better recapitulated in dcs_A_3 and dcs_A_4 than in dcs_B_2 (compare Fig 4A and B, right insets) where the long arm is more twisted in the NMR structure than in the design model; full control over β-sheet geometry in these folds likely requires control over sidechain packing between the β-sheet and the helical lid.

The crystal structures of fold C and D (Figs. 4C and 4D) are very close to the design models with designed aromatic packing and hydrogen bonding interactions bridging the protein core and the cone base; a designed disulfide bond is also correctly recapitulated (Fig. 4C, bottom inset). The two crystal structures for fold E monomeric designs also closely match the design models (Figs. 4E and 4F) with the cone base capped by the C-terminal helix in two different orientations. A buried cavity designed in one of these (dcs_E_3) expands toward the cone base in the crystal structure (Fig. 4F and fig. S21). We explored the ability of the fold C and D designs to support cavities by reducing the size and increasing the polarity of sidechains at the cone base (fig. S18). Five of the nine redesigns tested (with up to 19 mutations) were soluble and monomeric (figs. S19 and S20; table S1).

The crystal structure of the designed homodimer dcs_E_4_dim9 closely matches the computational model over both the individual subunits and the designed β-sheet interface (Fig. 4G and fig. S22). We designed large cavities by truncating sidechains at the cone base (figs. S18 and S20). The crystal structure of one such design revealed a large (520 Å3) cavity very similar to that in the design model, lined by the curved β-sheet (Fig. 4H; a pentaethylene glycol fills the cavity). This is the largest de novo designed cavity to date, and illustrates how large core packing vacancies can be programmed by designing curved β-sheets topped by helices.

The nine NMR and crystal structures show that β-sheet curvature can be accurately programmed with the principles we have identified. The designed proteins exhibit a rich combination of structural features: curved β-sheets with β-bulges and register shifts, loops of variable length, helices, disulfide bonds, β-sheet interfaces and cavities. Stability can be increased using disulfide bonds and homodimer interfaces without interfering with the accessibility of potential binding pockets, allowing substitution of large hydrophobics to smaller or polar residues to line solvent-exposed clefts and buried cavities.

Computational methods have been used to design enzyme catalysts by defining an ideal active site (“theozyme”) and then searching for placements of the theozyme in native protein scaffolds. This approach has yielded catalysts for a number of chemical reactions, including reactions not catalyzed by naturally occurring enzymes, but the activities are quite low. This likely result from two shortcomings in the design strategy: the detailed theozyme geometry cannot be perfectly realized in any pre-existing scaffold, and the sequence changes introduced in the design process can produce unpredictable changes in structure (6, 7). Our de novo design framework should make it possible to overcome both limitations by custom designing backbones for the reaction of interest.

Supplementary Material

One Sentence Summary.

Programming curvature into designed β-sheets gives routes to design solvent-accessible pockets.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Carter for assistance with SEC-MALS and protein production; J. Nguyen, A. Young-Seug, Z. Wang, M. Bick, S. Jayaraman and P. O’Connell for assistances in X-ray crystallography; all Baker lab members for discussions, and Rosetta@Home volunteers for computing resources used in ab initio structure prediction calculations. Work carried out at the Baker laboratory was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (Funding HDTRA 1-11-1-0041). X-ray diffraction data was collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source with beamline X4C (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, U.S. Department of Energy) and the Advance Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California Department of Energy). The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. E.M. was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship (FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IOF 298976). IRB Barcelona is the recipient of a Severo Ochoa Award of Excellence from MINECO (Government of Spain). GO. was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship (332094 ASR-CompEnzDes FP7-PEOPLE-2012-IOF). D.A.S is a Latin American PEW postdoctoral fellow and CONACyT postdoctoral fellow and acknowledges its support. This work was supported as a Community Outreach Activity of NIGMS PSI grant U54 GM094597 (to G.T.M).

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with the accession codes 5KPH (dcs_A_3), 4R80 (dcs_A_4), 5KPE (dcs_B_2), 5TS4 (dcsC1ss), 5L33 (dcs_D_2), 5TPJ (dcs_E_3), 5TRV (dcs_E_4), 5TPH (dcs_E_4_dim9) and 5U35 (dcs_E_4_dim9_cav3). NMR data have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank with the accession codes 30139 (dcs_A_3) and 30128 (dcs_B_2).

E.M. and D.B. designed the research; E.M. developed the β-sheet design principles and set up the design method; E.M., B.B. and T.M.C. carried out the design calculations, protein expression and biophysical characterization; E.M., B.B. and T.M.C. crystallized proteins from folds C, D and E; J.H.P. crystallized dcs_C_1_ss; Y.T. solved the NMR structures of dcs_A_3 and dcs_B_2 with help from G.L.; R.G. solved the crystal structure of dcs_A_4; G.O. and B.B. solved the crystal structures of dcs_C_1_ss, dcs_D_2, dcs_E_3, dcs_E_4, dcs_E_4_dim9 and dcs_E_4_dim9_cav3; G.V.T.S. collected HSQC data; R.X. prepared isotope-enriched protein samples for NMR structure determination; D.A.S. and E.M. developed the Biased ab initio folding protocol; J.D. designed and experimentally characterized cavity-creating mutations in dcs_D_2; B.S. and P.H.Z collected and analyzed crystallographic data; E.M., B.B., G.T.M and D.B. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials:

Materials and Methods

Input files and command lines for design calculations

References and Notes

- 1.Tinberg CE, Khare SD, Dou J, Doyle L, Nelson JW, Schena A, et al. Nature. 2013;501:212–216. doi: 10.1038/nature12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Röthlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, Dechancie J, Betker J, et al. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, Doyle L, Rothlisberger D, Zanghellini A, et al. Science. 2008;319:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1152692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel JB, Zanghellini A, Lovick HM, Kiss G, Lambert AR, St Clair JL, et al. Science. 2010;329:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1190239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopalan S, Wang C, Yu K, Kuzin AP, Richter F, Lew S, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:386–391. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter F, Blomberg R, Khare SD, Kiss G, Kuzin AP, Smith AJT, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16197–16206. doi: 10.1021/ja3037367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giger L, Caner S, Obexer R, Kast P, Baker D, Ban N, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:494–498. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joh NH, Wang T, Bhate MP, Acharya R, Wu Y, Grabe M, et al. Science. 2014;346:1520–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1261172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson AR, Wood CW, Burton AJ, Bartlett GJ, Sessions RB, Brady RL, et al. Science. 2014;346:485–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1257452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle L, Hallinan J, Bolduc J, Parmeggiani F, Baker D, Stoddard BL, et al. Nature. 2015;528:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature16191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton DNWA, Thomson A, Dawson W, Brady R. Nat Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nchem.2555. DOI: 10.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koga N, Tatsumi-Koga R, Liu G, Xiao R, Acton TB, Montelione GT, et al. Nature. 2012;491:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang PS, Oberdorfer G, Xu C, Pei XY, Nannenga BL, Rogers JM, et al. Science. 2014;346:481–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1257481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y, Koga N, Tatsumi-Koga R, Liu G, Clouser AF, Montelione GT, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:E5478–E5485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509508112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunette T, Parmeggiani F, Huang PS, Bhabha G, Ekiert DC, Tsutakawa SE, et al. Nature. 2015;528:580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature16162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang P-S, Feldmeier K, Parmeggiani F, Fernandez Velasco DA, Höcker B, Baker D. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:29–34. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs TM, Williams B, Williams T, Xu X, Eletsky A, Federizon JF, et al. Science. 2016;352:687–690. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson JS, Getzoff ED, Richardson DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:2574–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan AW, Hutchinson EG, Harris D, Thornton JM. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1574–1590. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chothia C. J Mol Biol. 1983;163:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salemme FR. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1983;42:95–133. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(83)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leaver-Fay A, Tyka M, Lewis SM, Lange OF, Thompson J, Jacak R, et al. Methods Enzymol. 2011;487:545–574. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381270-4.00019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials at the Science website.

- 24.Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D. 2003;302:1364–1369. doi: 10.1126/science.1089427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craveur P, Joseph AP, Rebehmed J, De Brevern AG. Protein Sci. 2013;22:1366–1378. doi: 10.1002/pro.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara K, Ebisawa S, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara H, Ikeguchi M. BMC Struct Biol. 2015;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12900-015-0048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohl CA, Strauss CEM, Misura KMS, Baker D. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley P, Misura KMS, Baker D. Science. 2005;309:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1113801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.