Abstract

Critical care nurses are vital to promoting family engagement in the intensive care unit. However, nurses have varying perceptions about how much family members should be involved. The Questionnaire on Factors That Influence Family Engagement was given to a national sample of 433 critical care nurses. This correlational study explored the impact of nurse and organizational characteristics on barriers and facilitators to family engagement. Study results indicate that (1) nurses were most likely to invite family caregivers to provide simple daily care; (2) age, degree earned, critical care experience, hospital location, unit type, and staffing ratios influenced the scores; and (3) nursing workflow partially mediated the relationships between the intensive care unit environment and nurses’ attitudes and between patient acuity and nurses’ attitudes. These results help inform nursing leaders on ways to promote nurse support of active family engagement in the intensive care unit.

Keywords: critical care, family caregivers, family-centered nursing, family engagement

An increasing number of Americans require treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU), and a proportional increase in family caregivers will assume caregiving responsibilities that can have persistent negative effects on their health and overall quality of life.1–6 The conventional ICU care paradigm has primarily targeted the informational needs of family caregivers of the critically ill, but has not addressed how to actively engage caregivers in other aspects of the ICU experience such as symptom assessment and the direct provision of care.7–10 Although critical care research, policy, and practice guidelines9,10 increasingly recognize family caregivers as part of a larger patient-provider interaction during critical illness, the literature on family caregiver engagement in this context mainly focuses on passive forms of involvement such as family presence, communication, and decision-making. Few studies address family caregivers’ active contributions to patient care.7,8,11–18

Patient and family engagement are defined as active partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families.7 Identifying effective ways to implement patient and family engagement is paramount to improving the patient and family experience as well as improving safety, quality, and delivery of care.7–9 In the ICU, critical care nurses are the frontline providers of life-sustaining care and key staff members in promoting patient and family engagement. However, the literature provides evidence that critical care nurses express resistance to involving family caregivers because of misconceptions such as families’ interfering with care, exhausting the patient, and spreading infection.2,19–21 Nurses have expressed concerns regarding the safety of family engagement in care in relationship to patients’ severity of illness and their fluctuations in acuity while receiving care in the ICU.2,4,14,18,20,22,23

In addition, nurses have varying perceptions regarding best practices for involving family caregivers while maintaining patient privacy and safety, and there is a paucity of organizational and unit policies and procedures to guide nurses to implement patient and family engagement safely and effectively.8,18–20,22,23

In previous studies, aspects of the ICU environment such as physical layout, staffing, resource availability, and overall unit perception of family engagement as well as issues related to critical care nurses’ general workflow greatly influenced nurses’ perceptions of the effort and time required to effectively engage family in patient care.2,4,14,18,20,22,23 Further exploration of these factors will help inform the promotion of patient and family engagement in the ICU and identify strategies to help nurses embrace family caregivers as active participants in patient care.

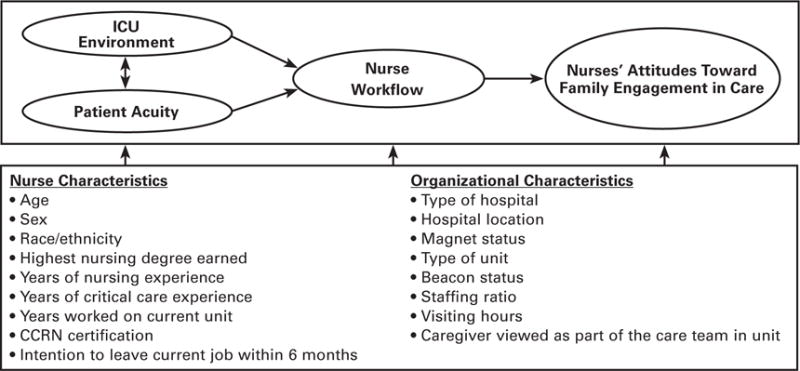

To encourage collaborative partnerships among patients, families, and critical care nurses, we must first understand the perceived barriers and facilitators that critical care nurses face regarding engagement of family caregivers in patient care. To guide this study, a conceptual model (Figure 1) was developed with evidence from empirical studies of factors that facilitate the inclusion of caregivers in direct patient care activities in the ICU and beyond.2,4,14,18,20,22,23 Model assumptions are that the ICU environment of care and patient acuity affect nursing workflow and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement in care. Individual, intrinsic nurse and organizational factors may also influence nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement in care. Nursing workflow seems to mediate the effects of the ICU environment and patient acuity on nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement.17–19,23

Figure 1.

Perceived barriers to and facilitators of family engagement in care. Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

No descriptive study of a national sample of critical care nurses in the United States has aimed to examine the various perceived factors that influence critical care nurses’ inclusion of family caregivers in the care of critically ill patients. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to (1) report patient care activities nurses commonly offer to family caregivers to perform; (2) explore the impact of nurse and organizational characteristics on barriers and facilitators to family engagement in care; and (3) examine the relationships among ICU environment, patient acuity, nurse workflow, and attitudes toward family engagement in the care of the critically ill.

Method

We used a descriptive, correlational study of a national sample of critical care nurses providing direct patient care to critically ill patients. Prior to participant recruitment and data collection, institutional review board approval was obtained.

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit eligible critical care nurses and consisted of advertisements explaining the purpose of the study and describing eligibility criteria via electronic communications and social media sites of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). Participants in this study met the following criteria: (1) employed as a critical care nurse in an ICU and (2) responsible for the direct care of critically ill patients and their families for more than 20 hours each week.

Measures

Nurse and Organizational Characteristics

To address the goals of this study, nurse and organizational characteristics were assessed using an investigator-developed demographic instrument. These data included age, sex, race/ethnicity (ie, white vs nonwhite), educational status, years of ICU experience, CCRN certification status, type of ICU (eg, adult, pediatric), Beacon and Magnet status, staffing ratio, job satisfaction (single item indicator: “Do you intend to leave your current position within the next 6 months?”), and unit culture (single item indicator: “Do you feel family caregivers are viewed as part of the team in your current unit?”) about whether family caregivers are viewed as part of the care team. In addition, nurses were asked to indicate from a pre-established list which patient care activities they would feel comfortable inviting family caregivers to perform or assist in providing.

Questionnaire on Factors That Influence Family Engagement

The Questionnaire on Factors That Influence Family Engagement (QFIFE) is a self-report measure of the perceived barriers and facilitators that affect the critical care nurse’s attitudes toward family engagement in the care of a critically ill patient. This investigator-developed instrument was derived from a review of the literature and 2 established measures.2,19 The QFIFE is a 15-item questionnaire that consists of 4 subscales: (1) ICU environment (items 1–5), (2) patient acuity (items 6–7), (3) nurse workflow (items 8–10), and (4) attitude toward family caregiver engagement in care (items 11–15). These subscales measure the nurse perceptions of the physical environment and culture of the ICU, clinical stability of the patient, disruptive workflow, and the attitude toward family engagement in the delivery of ICU care. Items fall along a 6-point Likert scale from 1 to 6 and items 6 to 10 require reverse coding prior to the calculation of total and subscale mean scores. Higher mean scores indicate a greater magnitude of the influence of the perceived facilitators to family engagement in patient care. This QFIFE established internal consistency reliability for the total and subscale scores with α coefficients of ICU environment at 0.73; patient acuity, 0.77; nurse workflow, 0.74; and attitude toward family caregiver engagement in care, 0.83.

Procedures

Data Collection

Participant recruitment and data collection were conducted electronically during July and August 2016 through postings on the AACN social media sites and listserv. The postings contained a description of the study and a hyperlink to the electronic surveys. Qualtrics Survey Software was used to electronically administer the demographic and organizational form and the QFIFE. The first 100 participants to complete the electronic survey, which took 15 to 20 minutes, received a $5 electronic gift card.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis to determine nurse and organizational characteristics of respondents and to identify the most common patient care activities nurses invite family members to participate. Because the QFIFE was new, we examined whether the 15 items in the 4 subscales accurately represented barriers and facilitators to family engagement (ie, exploratory factor analysis). Next, we perfomed an examination of the impact of nurse and organizational characteristics on total mean QFIFE score (one-way between group analysis of variance tests and independent-sample t tests). Lastly, multiple linear regression testing was conducted to examine the relationships among (1) the ICU environment, (2) patient acuity, (3) nurse workflow, and (4) attitudes toward family engagement. Additional analysis using Sobel’s test was conducted to test nursing workflow as a mediator between the predictor variables (ie, ICU environment and patient acuity) and the outcome variable (ie, attitudes toward family engagement).24 Data analyses were run in IBM SPSS Statistics version 24. Results were considered significant a priori if P was less than .05.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 433 participants, 86% were white, 91% were females, 51% were between the ages of 30 and 49, and 66% had a bachelor’s degree. Only 11.1% of the participants in this sample had less than 1 year of critical care experience, and less than half had a CCRN. More than one-third of participants were primarily employed at academic medical centers; most of the academic medical centers were located in urban and suburban settings. A total of 80.4% of participants worked in adult ICUs, 78.3% reported that their ICU had open visitation policies, and 66% reported that their unit culture valued family engagement (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics (N = 433)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| < 25 | 34 (7.9) |

| 25–29 | 83 (19.2) |

| 30–49 | 219 (50.6) |

| > 49 | 97 (22.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 38 (8.8) |

| Female | 393 (90.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 374 (86.4) |

| Nonwhite | 59 (13.6) |

| Highest nursing degree earned | |

| Diploma | 9 (2.1) |

| Associate’s | 66 (15.2) |

| Bachelor’s | 285 (65.8) |

| Master’s | 65 (15.0) |

| Doctorate | 8 (1.8) |

| Years of critical care experience | |

| < 1 | 48 (11.1) |

| 1–5 | 162 (37.4) |

| 6–15 | 125 (28.9) |

| > 15 | 98 (22.6) |

| CCRN certification | |

| Yes | 197 (45.5) |

| No | 235 (54.3) |

| Type of hospital currently working | |

| Academic medical center | 164 (37.9) |

| Community hospital (teaching) | 132 (30.5) |

| Community hospital (nonteaching) | 121 (27.9) |

| Military | 4 (0.9) |

| Other | 12 (2.8) |

| Hospital location | |

| Urban | 329 (76.0) |

| Suburban | 86 (19.9) |

| Rural | 18 (4.2) |

| Magnet status | |

| Yes | 178 (41.1) |

| No | 232 (53.6) |

| Unsure | 23 (5.3) |

| Type of unit | |

| Adult ICU | 348 (80.4) |

| Pediatric ICU | 29 (6.7) |

| Other | 56 (12.9) |

| Beacon status | |

| Yes | 90 (20.8) |

| No | 234 (54.0) |

| Unsure | 109 (25.2) |

| Years worked on current unit | |

| < 1 | 83 (19.2) |

| 1–5 | 193 (44.6) |

| 6–15 | 107 (24.7) |

| > 15 | 50 (11.5) |

| Intend to leave current position within 6 months | |

| Yes | 71 (16.4) |

| No | 362 (83.6) |

| Staffing ratio on unit | |

| 1 nurse to 1 patient | 22 (5.1) |

| 1 nurse to 2 patients | 370 (85.5) |

| 1 nurse to 3 patients | 23 (5.3) |

| Variable | 18 (4.1) |

| Visiting hours on unit | |

| Open visitation | 339 (78.3) |

| Limited visitation | 72 (16.6) |

| Other | 22 (5.1) |

| Caregivers viewed as part of team on unit | |

| Yes | 286 (66.1) |

| No | 147 (33.9) |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit.

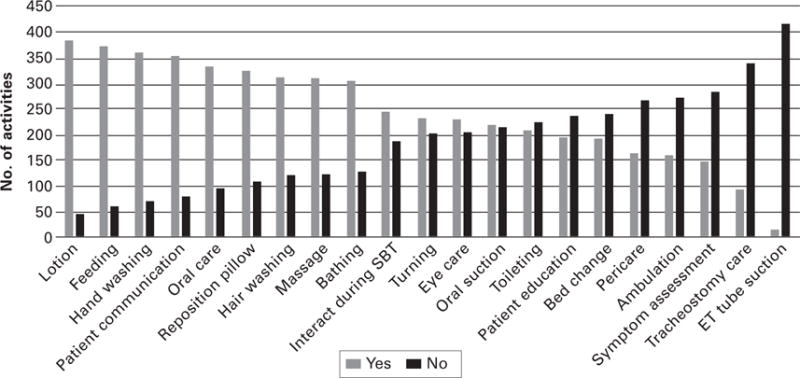

Care Activities Offered to Families

Of the patient care activities offered to families, nurses were most likely to invite family caregivers to perform simple daily tasks such as applying lotion, feeding the patient, washing the patient’s hands, and communicating with the patient. Nurses were less likely to ask family caregivers to help with more intimate or invasive care measures such as toileting (48.0%) and perineal care (38.1%) or activities more specifically related to a skilled nursing role, including symptom assessment (34.4%), tracheostomy care (21.7%), and endotracheal tube suctioning (3.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Care activities in which nurses invite family caregivers to perform or assist. Abbreviations: ET, endotracheal tube; SBT, spontaneous breathing trial.

Impact of Nurse and Organizational Characteristics on Total Mean QFIFE Score

The QFIFE subscale scores ranged from 3.52 for the ICU environment to 4.54 for nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement (Table 2). The lowest-scoring item on the QFIFE was item 3, “My unit has established written policies regarding involving family caregivers in care,” and the highest-scoring item was item 13, “I think that family caregivers who are involved in patient care are better able to make care decisions for their loved one” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Scores on the Questionnaire on Factors That Influence Family Engagement (N = 433)

| Subscalea | Mean (SD) | Range | Variance | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU environment | 3.52 (0.95) | 1.58 | 0.35 | 0.73 |

| 1. My unit is physically set up in a way that makes involving family caregivers in patient care possible. | 4.24 (1.26) | |||

| 2. My unit is adequately staffed to allow me time to involve family caregivers in patient care. | 3.66 (1.29) | |||

| 3. My unit has established written policies regarding involving family caregivers in patient care. | 2.66 (1.30) | |||

| 4. My unit supports family caregiver presence during procedures (eg, resuscitation, line placement). | 3.29 (1.43) | |||

| 5. There is designated space and there are resources for families who wish to remain with their loved ones in the ICU. | 3.77 (1.58) | |||

| Patient acuity | 3.93 (1.15) | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.77 |

| 6. Family caregivers of patients who are hemodynamically unstable should be excluded from participating in patient care. | 3.60 (1.34) | |||

| 7. Patients on life-sustaining treatments should not have family caregivers involved in patient care. | 4.26 (1.21) | |||

| Nurses’ workflow | 4.16 (0.99) | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.74 |

| 8. Allowing family caregivers to assist in patient care interrupts my work. | 3.91 (1.16) | |||

| 9. My clinical performance will be affected by the presence of family caregivers in the room while I am providing patient care. | 4.45 (1.24) | |||

| 10. I’m too busy to incorporate family caregivers in patient care. | 4.12 (1.26) | |||

| Nurses’ attitudes | 4.54 (0.77) | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.83 |

| 11. Allowing family caregivers to assist in patient care could help me more accurately assess distressing symptoms in my patients. | 4.14 (1.11) | |||

| 12. Allowing family caregivers to assist in daily patient care could improve caregiver levels of stress, anxiety, and fear. | 4.75 (0.88) | |||

| 13. I think that family caregivers who are involved in patient care are better able to make care decisions for their loved ones. | 4.79 (0.92) | |||

| 14. I think involving family caregivers in patient care improves patient safety. | 4.29 (1.10) | |||

| 15. I think involving family caregivers in patient care increases overall quality of care. | 4.74 (0.95) |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

The theoretical range for all subscales is 1 to 6. Higher mean scores indicate a greater magnitude of the influence of the perceived facilitators to family engagement in patient care.

Total mean QFIFE scores were calculated, and the effects of age, degree earned, critical care experience, hospital location, unit type, and staffing ratios on QFIFE scores were significant (Table 3). Participants who were older with more critical care experience as well as those with advanced degrees had higher mean QFIFE scores. Participants who worked in rural hospitals, worked in pediatric ICUs, and those with lower staffing ratios also had higher mean QFIFE scores. Participants who intended to leave their current nursing positions within the next 6 months and those who worked on units that did not view caregivers as part of the care team had lower mean QFIFE scores (Table 4).

Table 3.

Impact of Selected Nurse and Organizational Demographic Variables on Factors That Influence Family Engagement Questionnaire

| Variable | Mean (SD) | SS | F(df) | MS | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 10.51 | 8.19 (3) | 3.50 | < .001 | |

| < 25 | 4.22 (0.51) | ||||

| 25–29 | 3.87 (0.69) | ||||

| 30–49 | 3.97 (0.67) | ||||

| > 49 | 4.29 (0.62) | ||||

| Degree | 4.58 | 2.58 (4) | 1.14 | .04 | |

| Diploma | 4.14 (0.58) | ||||

| Associate’s | 4.04 (0.72) | ||||

| Bachelor’s | 4.00 (0.65) | ||||

| Master’s | 4.15 (0.66) | ||||

| Doctorate | 4.68 (0.78) | ||||

| Critical care experience, y | 8.09 | 6.22 (3) | 2.69 | < .001 | |

| < 1 | 4.11 (0.69) | ||||

| 1–5 | 4.02 (0.65) | ||||

| 6–15 | 3.88 (0.67) | ||||

| > 15 | 4.26 (0.65) | ||||

| Hospital location | 2.75 | 3.09 (2) | 1.38 | .046 | |

| Urban | 4.04 (0.67) | ||||

| Suburban | 3.98 (0.61) | ||||

| Rural | 4.41 (0.79) | ||||

| Unit type | 18.71 | 22.93 (2) | 9.36 | < .001 | |

| Adult | 3.96 (0.65) | ||||

| Pediatric | 4.78 (0.50) | ||||

| Other | 4.15 (0.61) | ||||

| Staffing ratio | 3.09 | 3.44 (2) | 1.54 | .03 | |

| 1 nurse to 1 patient | 4.32 (0.63) | ||||

| 1 nurse to 2 patients | 4.04 (0.67) | ||||

| 1 nurse to 3 patients | 3.79 (0.70) |

Abbreviations: MS, mean squares; SS, sum of squares.

Table 4.

Impact of Nurse Job Satisfaction and Perception of Unit Culture on Factors That Influence Family Engagement Questionnaire

| Variable | Score, mean (SD) | t (df) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction (nurse’s intention to leave within 6 months) | −2.95 (431) | .003 | |

| Yes | 3.83 (0.62) | ||

| No | 4.08 (0.67) | ||

| Unit culture (caregivers viewed as part of team on unit) | 7.7 (431) | <.001 | |

| Yes | 4.21 (0.64) | ||

| No | 3.72 (0.61) |

ICU Environment, Patient Acuity, Nurse Workflow, and Nurse Attitudes Toward Family Engagement

There were 3 models looking at the influence of ICU environment on nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement (Table 5). Model 1 estimated the relationship between ICU environment (β = .34, P <.001) and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement. Model 2 estimated the relationship between nurse workflow (β = .45, P <.001) and attitude toward family engagement. Model 3 estimated the relationship between ICU environment (β = .22, P <.001) and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement while accounting for the effects of nurse workflow. Model 1 showed a direct relationship between ICU environment and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement. Model 2 showed a direct relationship between nurse workflow and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement. Model 3 showed a significant relationship between ICU environment and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement when accounting for the effects of nurse workflow. Nursing workflow partially mediated the relationship between the ICU environment and the attitude toward family engagement among nurses (Sobel test = 4.2, P < .001).

Table 5.

Influence of ICU Environment and Nurse Workflow on Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Family Engagement

| Predictor | Attitude Toward Family Engagementa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | Model 3 | Model 3 | |

| ICU environment | 0.34b | — | 0.22b |

| Nurse workflow (mediator) | 0.45b | 0.37b | |

| R | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.49 |

| R2adj | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| F | 58b | 107b | 68b |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

The standardized regression coefficients (β) for the variables are reported in this table. The sample size is 432 participants.

P < .001.

Two other models described the influence of patient acuity on nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement (Table 6). Model 4 estimated the relationship between patient acuity (β = .37, P <.001) and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement. Model 5 estimated the relationship between patient acuity (β = .23, P <.001) and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement while accounting for the effects of nurse workflow. Model 4 showed a significant direct relationship between patient acuity and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement. Model 5 showed a significant relationship between patient acuity and nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement when accounting for the effects of nurse workflow. Nursing workflow partially mediated the relationship between patient acuity and the attitude toward family engagement among nurses (Sobel test = 4.3, P <.001).

Table 6.

Influence of Patient Acuity and Nurse Workflow on Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Family Engagement

| Predictor | Attitude Toward Family Engagementa |

|

|---|---|---|

| Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| ICU environment | 0.37b | 0.23b |

| Nurse workflow (mediator) | 0.36b | |

| R | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| R2adj | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| F | 67b | 69b |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

The standardized regression coefficients (β) for the variables are reported in this table. The sample size is 432 participants.

P < .001.

Discussion

Our study was one of the first investigations of a national sample of critical care nurses to report the patient care activities that nurses invite family caregivers to participate in, explore the impact of nurse and organizational characteristics on the perceived barriers and facilitators to family engagement in the ICU, and examine the relationships among the perceived barriers and facilitators.

Similar to the results from previous studies,22,25,26 these QFIFE survey results indicated nurses had a positive attitude toward family engagement and did not view family engagement as a hindrance to their clinical performance. Nurses agreed that allowing family caregivers to assist in patient care could help with symptom assessment and improve patient safety, decision-making, and overall quality of care as well as improve caregivers’ levels of stress, anxiety, and fear. However, nurses had mixed feelings about the extent to which caregivers should be involved in light of high patient acuity. Nurses were more likely to invite family caregivers to provide simple, noninvasive daily care activities than more intimate, invasive, or technically skilled measures. This finding is consistent with prior studies in which activities such as bathing, passive range of motion, eye care, and mouth care were found to be more likely approved by nurses and relatives.20,23,27 Hammond23 examined family members’ perspectives and found that although most families want to be involved in the physical care of the patient, an activity such as incontinence care is not something that the family wants to take part. Nurses also expressed concern about the safety and appropriateness of some care measures.22

As suggested in prior studies, family participation must be tailored to each family’s needs as assessed by nursing staff.27 However, additional research is needed to establish criteria to classify caregivers (eg, caregiver knowledge base, previous care experience, motivation, self-efficacy, preparedness) to help nurses tailor their approach to engagement with each family caregiver. Additional education and training may be needed for nurses to understand their role in communicating opportunities and safely guiding family involvement within the ICU environment. We evaluated the nurses’ perceptions of family engagement in consideration of CCRN, Magnet, and Beacon status and found that neither individual nor organizational achievement of certification was associated with higher QFIFE mean scores. According to AACN, “Achieving certification demonstrates to patients, employers and the public that a nurse’s knowledge, skills and abilities meet rigorous national standards—and reflects a deep commitment to patient safety,”28 but previous studies have not demonstrated the effectiveness of nursing, unit, and hospital certification on patient and family outcomes.29 Further evaluation of the impact of certification on patient and family outcomes in the ICU is needed, and certifying bodies should take steps to incorporate components of patient and family engagement to promote expertise and quality of care.

In our sample, the effects of nurse and organizational characteristics—specifically age, degree earned, critical care experience, hospital location, unit type, staffing ratios, job satisfaction, and unit culture—on total mean QFIFE score were significant. In contrast, Al-Mutair et al22 did not find any differences in nurse demographics and attitudes towards family involvement in care.

Our results suggest that the youngest and olders nurses viewed patient family engagement more favorably than did nurses aged 25 to 49 years. Nurses with more critical care experience and those with a doctoral degree were more supportive of family engagement. In a study testing the effects of a family nursing educational intervention, Eggenberger and Sanders30 found that nurses had more confidence, knowledge, and family skills after participating in a 4-hour workshop addressing family experiences with critical illness. Thus, nursing experience and opportunities to learn about foundational elements of family care are vital for establishing relationships with family members and encouraging family caregiver participation.

Our results also indicate that those who worked in the context of lower staffing ratios (ie, 1 nurse to 1 patient or 1 nurse to 2 patients) were more supportive of family engagement. A 2010 literature review suggested that a decrease in nurse staffing and an increase in nurse workload were both associated with adverse patient outcomes.31 Given the current nursing shortage as well as the resource and financial strain of providing critical care services to an aging population, innovative solutions such as leveraging technology to decrease nurse workload and the use of advanced practice nurses in the ICU to ensure care continuity should be considered as ways to support the practice of family engagement.31,32 Further research is needed to understand the relationship among nurse demographics, nurse work environment factors, and attitudes and practices related to family engagement in patient care.

Only 66% of the nurse respondents reported having a unit culture that valued family engagement. Further, most participants selected “strongly disagree” or “disagree” when asked if their unit had policies and procedures to support their inclusion of family members in care. Other studies have cited legal issues, inadequate procedural guidelines, and lack of nursing education related to family involvement as significant barriers to implementing family engagement practices.2,22 Current guidelines exist for family support9,10; however, most organizations have not instituted all recommended practices for family care in the ICU. Family participation requires a systematic assessment of organizational and unit-based family care philosophies and family support resources. If nurses are expected to engage caregivers, there must be readily available, evidence-driven policies and procedures supported by current practice guidelines9,10 to help standardize patient care and support nurses’ decisions on how to involve family members.

Patient acuity and care in the ICU predicted nursing attitudes and beliefs toward family engagement, which were mediated by nursing workflow. In a qualitative research study, nursing workflow emerged as an influential factor in the establishment of nurse-family relationships.33 In another study, nurses identified lack of time and the complexity of critically ill patients as barriers to involvement of family members.2 Family engagement is negatively impacted by nurses’ task-oriented approaches to care, negative workplace conditions, and other nursing factors such as lack of competence or lack of motivation.33 Patient acuity and the ICU environment have the propensity to affect nursing workflow by increasing demands on the nurse, which in turn may decrease family caregiver involvement. The model we tested (Figure 1) can be used to help ICU leaders evaluate and target individual factors in their unit related to ICU environment, patient acuity, and nurse workflow to enhance nurses’ attitudes toward family engagement in the care of ICU patients.

Although previous studies have shown that family engagement in the ICU helps improve communication and build relationships between families and health care staff,22,33 properly educating family caregivers in patient care in the ICU environment requires resources.2 A close examination of ICU family culture, staffing decisions, patient acuity, and other work environmental factors is required to develop solutions to alleviate time constraints and promote a milieu that supports family engagement in critical care.20,22,30,33 More research using objective measures of patient safety and care quality is needed to examine the benefits and potential risks of family involvement.

Few studies have adequately measured psychological, physiological, financial, and functional family outcomes related to participation in the care of a critically ill family member. However, preliminary evidence suggests that family engagement in the ICU can increase family member presence and interaction with the patient; improve the perception of respect, collaboration, and support between family members and health care staff; and reduce family members’ anxiety and stress.8,14,31 Thus, family outcomes also require further exploration.

Repeated measures and longitudinal designs are recommended to study how family involvement influences family outcomes during and after the critical care experience. Most importantly, there is a need for further study of the current state of family nursing practice with emphasis on existing barriers to implementation of inclusive family care. Clinicians, unit managers, and researchers must work collaboratively to develop policies that support nurse-family partnerships in the ICU environment.

Limitations

Limitations to our study include our use of a descriptive design and a convenience sample of ICU nurses from the AACN electronic communications and social media sites. Our sample was small relative to AACN membership size, and the possibility of nonrespondent bias, because only those who were interested in the subject matter completed the survey, limits the generalizability of our results. Also, our study sample lacked racial, ethnic, and gender diversity. The QFIFE survey used in this study was developed from a review of the literature and 2 established measures. Whereas we conducted a preliminary factor analysis to establish reliability and validity in this sample, a full psychometric analysis and repeated testing are needed to adequately define the sample’s psychometric properties.

Conclusion

The benefits of family engagement in the ICU have been well established,1–17 yet most research has focused on family presence, visitation, and decision-making, with little research done to explore active family contributions to patient care.8 Effective implementation of active family engagement begins with the endorsement of the bedside nurse. We must understand how nurses view family engagement and the barriers they face when working to involve family members in patient care. The results of our study indicate a need look into staffing, space and resources for families, unit culture, and the establishment of policies and procedures that outline the role of family caregivers.

Our findings provide a foundation for exploring the scope, extent, and nature of family involvement in the ICU.8 The results can be used to inform nursing leaders how to target educational and training interventions as well as how to assess resource allocation and policies to reduce barriers to promote nurse support of active family engagement in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by funding (grant 4T32NR014213-04) from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content of the work does not necessarily represent official views of the NINR or the NIH.

Contributor Information

Breanna Hetland, Postdoctoral Fellow, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH.

Ronald Hickman, Associate Professor, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

Natalie McAndrew, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Medical Intensive Care Unit, The Medical College of Wisconsin-Froedtert Hospital, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Barbara Daly, Professor, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

References

- 1.Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10):1947–1953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ef4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McConnell B, Moroney T. Involving relatives in ICU patient care: critical care nursing challenges. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(7-8):991–998. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickman R, Douglas S. Impact of chronic critical illness on the psychological outcomes of family members. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2010;21(1):80–91. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c930a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hupcey JE. Looking out for the patient and ourselves— the process of family integration into the ICU. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(3):253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Dongelmans DA, van der Schaaf M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Weissfeld LA, et al. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SM, Rozenblum R, Aboumatar H, et al. Defining patient and family engagement in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):358–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1936LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S, et al. Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1183–1202. doi: 10.1111/hex.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson JE, Powers K, Medayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson JE. Facilitated sensemaking: a strategy and new middle-range theory to support families of intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(6):28–39. doi: 10.4037/ccn2010410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis LJ. The COPE program: a strategy to improve outcomes of critically ill young children and their parents. Pediatr Nurs. 1998;24(6):521–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arslanian-Engoren C, Scott LD. The lived experience of survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a phenomenological study. Heart Lung. 2003;32(5):328–334. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(03)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell M, Coyer F, Kean S, et al. Patient, family-centered care interventions within the adult ICU setting: an integrative review. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29(4):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Happ MB, Swigart VA, Tate JA, et al. Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Heart Lung. 2007;36(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen KD, Dysvik E, Hansen BS. The meaning of family members’ presence during intensive care stay: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurse. 2009;25(4):190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams C. The identification of family members’ contribution to patients’ care in the intensive care unit: a naturalistic inquiry. Nurs Crit Care. 2005;10(1):6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brien A, Clerehan R. Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(13-14):1805–1817. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Masri MM, Fox-Wasylyshyn SM. Nurses’ roles with families: perceptions of ICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurse. 2007;23(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Millems V, Timsit JF, et al. Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2010;25(4):634–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering With Families. Facts and Figures about Family Presence and Participation. http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/better-together-facts-and-figures_eng.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- 22.Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brian AP, Clerehan R. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards family involvement and presence in adult critical care units in Saudi Arabia: a quantitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(5-6):744–755. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond F. Involving families in care within the intensive care environment: a descriptive survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurse. 1995;11(5):256–264. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(95)81713-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benzien E, Johansson P, Arestedt K, Saveman B. Nurses’ attitudes about the importance of families in nursing care: a survey of Swedish nurses. J Fam Nurs. 2008;14(2):162–180. doi: 10.1177/1074840708317058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher C, Lindhorst H, Mathews T, Munroe D, Paulin D, Scott D. Nursing staff attitudes and behaviors regarding family presence in the hospital setting. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(6):615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, Foster M. Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family-centered care in adult critical care. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(6):543–552. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Certification. https://www.aacn.org/certification?tab=First-Time%20Certification. Accessed March 31, 2017.

- 29.Biel M, Grief L, Patry LA, et al. The relationship between nursing certification and patient outcomes: a review of the literature. :1–16. http://www.nursing-certification.org/resources/documents/research/certification-and-patient-outcomes-research-article-synthesis.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2017.

- 30.Eggenberger SK, Sanders M. A family nursing educational intervention supports nurses and families in an adult intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29(4):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aragon Penoyer D. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in critical care: a concise review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1521–1528. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly MA, Angus D, Chalfin DB, et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Chest. 2014;125(4):1514–1517. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segaric CA, Hall WA. Progressively engaging: constructing nurse, patient, and family relationships in acute care settings. J Fam Nurs. 2015;21(1):35–56. doi: 10.1177/1074840714564787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]