Abstract

Diffuse neuromodulatory systems such as norepinephrine (NE) control brain-wide states such as arousal, but whether they control complex social behaviors more specifically is not clear. Octopamine (OA), the insect homolog of NE, is known to promote both arousal and aggression. We have performed a systematic, unbiased screen to identify OA receptor-expressing neurons (OARNs) that control aggression in Drosophila. Our results uncover a tiny population of male-specific aSP2 neurons that mediate a specific influence of OA on aggression, independent of any effect on arousal. Unexpectedly, these neurons receive convergent input from OA neurons and P1 neurons, a population of FruM+ neurons that promotes male courtship behavior. Behavioral epistasis experiments suggest that aSP2 neurons may constitute an integration node at which OAergic neuromodulation can bias the output of P1 neurons to favor aggression over inter-male courtship. These results have potential implications for thinking about the role of related neuromodulatory systems in mammals.

Introduction

Neuromodulators exert critical influences on neural circuit function and are thought to control internal states related to emotion, mood and affect (Bargmann, 2012; Marder, 2012). How they act to control these states, in different behavioral contexts, remains unclear. Norepinephrine (NE), for example, is released from broadly distributed fibers (Foote and Morrison, 1987; Schwarz et al., 2015), in a manner thought to promote generalized arousal (Pfaff et al., 2005; Espana et al., 2016). However, neuromodulators can also act in a more circuit-specific manner, altering the output of multifunctional decision networks (Briggman and Kristan, 2008; Marder, 2012). Understanding neuromodulation mechanistically in a given behavioral context requires identifying the cellular targets of relevant neuromodulators. This remains challenging in the mammalian brain, because of its complexity.

Invertebrate organisms provide attractive systems to investigate the circuit-level mechanisms of neuromodulator action in vivo, because of their compact nervous systems and powerful genetics (reviewed in (Bargmann, 2012; Bargmann and Marder, 2013)). Octopamine (OA), an invertebrate analog of NE, is well-known to influence aggressive behavior in both insects and crustaceans (e.g., (Livingstone et al., 1980); reviewed in (Roeder, 1999; Kravitz and Huber, 2003; Roeder, 2005). In Drosophila, OA synthesis and release are essential for aggression (Baier et al., 2002; Hoyer et al., 2008; Zhou and Rao, 2008), and specific subsets of OA neurons (OANs) required for this behavior have been identified (Certel et al., 2007; Zhou and Rao, 2008; Certel et al., 2010).

However, there remains considerable uncertainty about the circuit-level mechanism by which cellular targets of OA action influence aggression. Aggression involves a high level of arousal (Miczek et al., 2007) and OA, like NE, is well known to promote arousal in flies and other insects (e.g., (Bacon et al., 1995); reviewed in (Roeder, 2005; Nall and Sehgal, 2014). OAergic fibers in the Drosophila CNS, like NE fibers in vertebrates, are widespread (Monastirioti et al., 1995; Sinakevitch and Strausfeld, 2006). This might suggest that OA acts in a brain-wide manner to promote generalized arousal, thereby enhancing multiple behaviors including aggression (Adamo et al., 1995; Stern, 1999; van Swinderen and Andretic, 2003).

However, OA could also influence aggression through more circuit-specific mechanisms, for example by increasing the excitability of components of a dedicated aggression pathway (e.g., (Andrews et al., 2014); reviewed in (Hoopfer, 2016)). Alternatively, OA release could act on a multifunctional, flexible network that controls the choice between different social behaviors (Marder et al., 2005; Kristan, 2008), biasing its output towards aggression (Certel et al., 2007; Certel et al., 2010).

This issue could be addressed by identifying central OA receptor-expressing neurons (OARNs) relevant to aggression, but little is known about such cells. Four different OA receptors (OARs) have been identified in Drosophila (Han et al., 1998; Balfanz et al., 2005; Maqueira et al., 2005). It has been challenging to map the cellular distribution of these endogenous receptors in the fly brain (Kim et al., 2013; El-Kholy et al., 2015), due to their low levels of expression. Consequently OARNs that influence aggression, even weakly, have been identified only serendipitously (Luo et al., 2014).

Here we used a molecularly and anatomically unbiased approach to identify systematically central OARNs involved in aggression in Drosophila. Our results uncover a small population of male-specific OARNs, called aSP2, that specifically modulate aggression, but do not control generalized arousal. Unexpectedly, in addition to receiving OAergic input, these OARNs are also activated by P1 neurons, a male-specific population of interneurons that can promote both male courtship and aggression (reviewed in (Auer and Benton, 2016; Hoopfer, 2016)). This convergence suggests that aSP2 neurons may bias output from a social behavior network to promote aggression.

Results

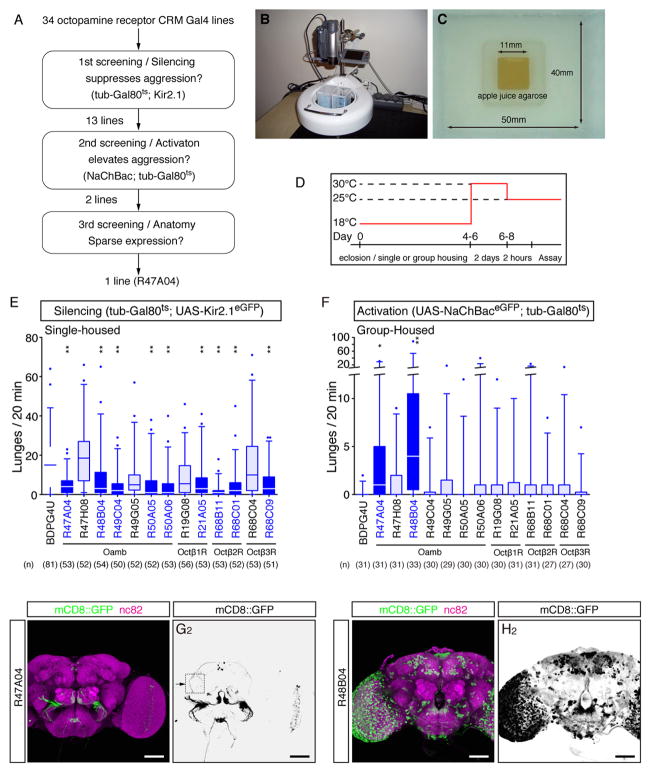

Identification of OA receptor-GAL4 lines that label aggression neurons

To identify OA receptor (OAR) neurons that control inter-male aggression in Drosophila, we performed a genetic behavioral screen for putative OAR-expressing neurons that, when silenced, decreased aggressive behavior (Fig. 1A–C). We generated 34 GAL4 driver lines containing molecularly defined cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) from all four known Drosophila OAR-encoding genes (Han et al., 1998; Balfanz et al., 2005; Evans and Maqueira, 2005; Maqueira et al., 2005) (Fig. S1A). We used UAS-Kir2.1, an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Baines et al., 2001), to silence neurons expressing GAL4, and included tubulin-GAL80ts (McGuire et al., 2003) to restrict Kir2.1 expression to the adult stage (thereby avoiding developmental lethality; Fig. 1D). We screened these 34 lines for decreases in aggressive behavior in pairs of single-housed males, using CADABRA software (Dankert et al., 2009) to automatically detect lunging, a typical aggressive behavior (Chen et al., 2002). From this initial screen, we recovered 13 hits that showed a decrease in the average frequency of lunging (Fig. 1A). To eliminate false positives, we performed a secondary screen of the hits from the primary screen using Kir2.1; 9 lines showed a significant decrease in aggression in this re-screen (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. R47A04 neurons are responsible for male-male aggressive behavior.

(A) Overview of strategy for screen to identify OARNs involved in aggression. (B and C) The experimental setup (B) and the behavioral arena (C) used in this behavioral screen (Hoyer et al., 2008). (D) Strategy for conditional silencing or activation using tub-GAL80ts. (E, F) Number of lunges in pairs of single- (E) or group-housed (F) male flies from GAL4 lines identified in the screen, during silencing using Kir2.1 (E) or activation using NaChBac (F). (G, H) Confocal images illustrating fly brains immunostained for mCD8::GFP expression (green) and the neuropil marker nc82 (magenta) in R47A04>mCD8::GFP (G) or R48B04>mCD8::GFP (H). Scale bars in panel G and H are 50 μm. For E and F, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. Here and throughout, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001 and ****: P<0.0001. Full genotypes for this and all subsequent figures are listed in Table S1.

Next, we asked whether any of the OAR-GAL4 lines identified in the initial, loss-of-function screen could, conversely, enhance aggression when their labeled neurons were constitutively activated. To do this, we expressed the bacterial sodium channel, NaChBac (Nitabach et al., 2006), in each of the 13 hits from the primary Kir2.1 screen with tub-GAL80ts. Of the 9 lines that re-screened as positives in the Kir2.1 secondary screen, two lines, derived from neighboring CRMs in the Oamb gene (Han et al., 1998), R47A04-GAL4 and R48B04-GAL4, showed an increase in lunging rate when activated using NaChBac (Fig. 1F and S1A).

To prioritize R47A04-GAL4 and R48B04-GAL4 for further investigation, we performed a preliminary expression analysis using a UAS-mCD8::GFP fluorescent reporter (JFRC2-10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP; (Pfeiffer et al., 2010)). This experiment revealed that R47A04-GAL4 labeled a much more restricted population of neurons than did R48B04-GAL4 (Fig. 1G, H). Based on this result, R47A04-GAL4 was selected for further analysis.

Manual behavioral annotation of R47A04-GAL4 crossed to either UAS-Kir2.1 or UAS-NaChBac confirmed the behavioral phenotypes detected by CADABRA software (Fig. S1B, E). This manual analysis revealed that silencing of R47A04 neurons not only decreased aggression, but also increased both the number of unilateral wing extensions (UWEs) towards the opponent male (a measure of courtship behavior) and the total time engaged in such behavior (Fig. S1C, D), suggesting an inhibitory influence. However, activation of R47A04 neurons did not reduce UWEs, although this could be due to a “floor effect” (Fig. S1F, G). Egg-laying, a behavior also known to be influenced by OA (Lee et al., 2003), was not affected by silencing of R47A04 neurons in females (Fig. S1H). Further studies indicated that the effects on aggression were not due to changes in locomotor activity (see below).

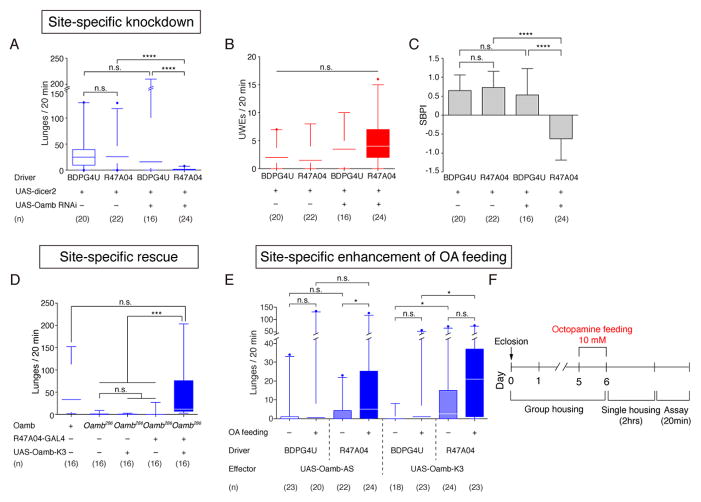

The OA receptor Oamb acts in R47A04 neurons to modulate aggression

Given that the activity of R47A04 neurons is necessary for normal levels of male aggression, and that these neurons were labeled using a CRM derived from the Oamb gene, we asked whether Oamb acts in these neurons to control aggressive behavior. Male flies homozygous for a Oamb null mutation, Oamb286 (Kim et al., 2013), showed a significant decrease in the number of lunges compared to genetic background-matched wild-type flies (Fig. 2D). In order to localize the site of Oamb function in aggressive behavior, we expressed Oamb cDNA in Oamb286 flies using R47A04 GAL4. Importantly, expression of Oamb in R47A04 neurons rescued aggression in Oamb286 males (Fig. 2D). Next, we expressed Oamb RNAi (Burke et al., 2012) under the control of R47A04-GAL4 to knock down Oamb in those neurons. Such flies also showed a significant decrease in lunging, as well as a trend to an increase in the frequency of UWE (Fig. 2A, B). To examine the effect of this manipulation on the relative proportion of courtship vs. aggression for each fly pair, we calculated a Social Behavior Proportion Index (SBPI; see the STAR Methods) for each pair of flies tested; values >0 indicate relatively more aggression, <0 indicates relatively more intermale courtship. Knockdown of Oamb in R47A04 neurons significantly shifted the average SBPI across all fly pairs from a bias towards aggression (SBPI ~ +0.5) towards male-male courtship (SBPI ~ −0.5; Fig. 2C). These results suggest that Oamb is required in R47A04 neurons to control the relative proportion of inter-male aggression vs. courtship.

Figure 2. Oamb acts in R47A04 neurons to control aggression.

(A–C) RNAi-mediated Oamb knock-down in R47A04 neurons during male-male social behaviors. Frequency of lunges (A) or unilateral wing extensions (UWEs) (B) and the SBPI (Social Behavior Proportion Index, see the STAR Methods, C) in R47A04>UAS-Oamb RNAi flies. For C, error bars denote ± S.D. (D) Frequency of lunges in Oamb mutant (Oamb286/Oamb286) male flies rescued by R47A04-GAL4 driving UAS-Oamb-K3. (E) Frequency of lunges after overexpression of Oamb cDNAs encoding either of two alternative splice variants, with or without 10 mM OA feeding. (F) Time-course of OA feeding for behavioral experiments. Note that the time-line is not to scale. For A–E, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed.

Next, we asked whether over-expression of Oamb in R47A04 neurons is sufficient to increase male-male aggressive behavior. Transcription of Oamb yields two isoforms, Oamb-AS and Oamb-K3, generated by alternative splicing; both isoforms promote an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ in response to OA (Lee et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2013). Overexpression of Oamb-K3 in R47A04 neurons caused a small but significant increase in aggression, compared to an “enhancer-less” GAL4 control (BDPG4U; Fig. 2E, OA feeding: −). Previous studies have shown that treatment of flies and other insects with OA or CDM (an OA agonist) promoted inter-male aggression (Stevenson et al., 2005; Zhou and Rao, 2008). However OA fed to control flies did not promote consistent increases in lunging under our conditions (Fig. 2E, F, BDPG4U, OA feeding: − vs +). One possible explanation for this result is that OA signaling in R47A04 neurons is already saturated under our conditions. To test this hypothesis, we asked whether Oamb overexpression could confer sensitivity to OA feeding. Indeed, OA feeding significantly enhanced lunging in R47A04>Oamb-K3 flies, compared to OA-fed control BDPG4>Oamb-K3 flies (Fig. 2E, OA feeding: +). Aggression in OA-fed R47A04>Oamb-K3 flies also showed a trend to higher aggression compared to non-OA fed flies of the same genotype (Fig. 2E), but which did not reach significance after correction for multiple comparisons. These findings provide evidence that Oamb acting in R47A04 neurons can enhance intermale aggression in response to OA.

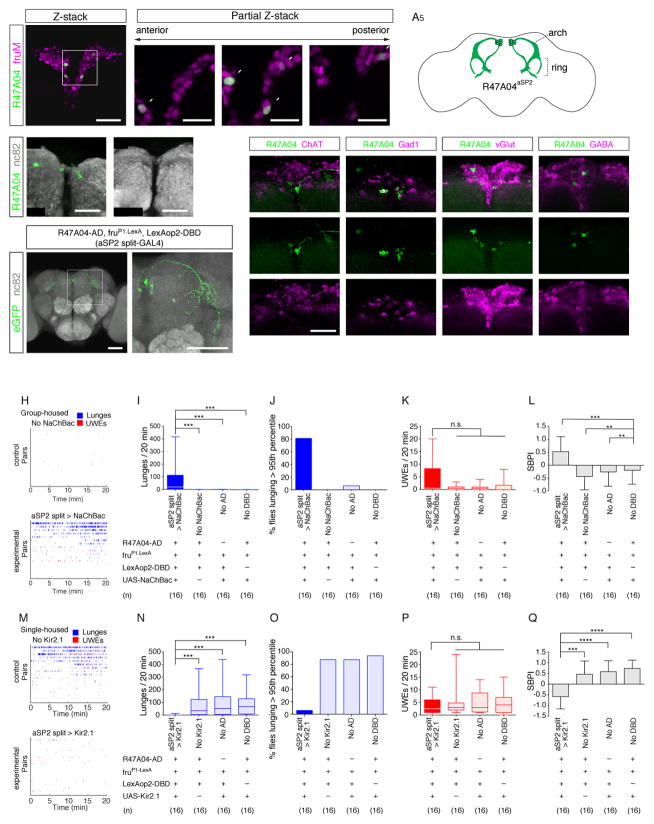

Fruitless-expressing aSP2 neurons in R47A04-GAL4 promote aggression

Expression analysis of R47A04-GAL4>mCD8::GFP revealed labeling in several locations in the central brain: the superior medial protocerebrum (SMP); the antennal nerve (AN), the antennal mechanosensory and motor center (AMMC) and subesophageal zone (SEZ) (Fig. 1G and S2A1). In addition to the expression in the central brain, GFP signals were observed in the ventral nerve cord (VNC) and maxillary palp, a secondary chemosensory organ (Fig. S2A2–3).

We therefore investigated which neurons within line R47A04 are responsible for the aggression phenotype. We performed intersectional experiments using Otd-FLPo and eyeless (ey)-FLPo with FLP-ON or FLP-OFF eGFP::Kir2.1 cassettes. These experiments indicated that aggression was reduced when eGFP::Kir2.1 was expressed in pattern containing the SMP cluster, but did not completely exclude a contribution from neurons in the AMMC or antenna, due to incomplete recombination (Fig. S2).

To gain more specific genetic access to the SMP cluster neurons, we performed further characterization of these cells in R47A04-GAL4. The SMP neurons arborize in a characteristic ring-shaped structure within the lateral protocerebral complex (Figs. 1G2, S2C2,8 and 3A5), which contains the projections of male-specific fruitless (fru)-expressing neurons (Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Dual reporter analysis using R47A04-LexA and fru-GAL4 (Stockinger et al., 2005) revealed that all of the SMP cluster neurons were fru-GAL4 positive (Fig. 3A1–4) and that these neurons were absent in the corresponding area of the female brain (Fig. 3B). Whether this reflects a lack of cells, or a lack of R47A04 enhancer activity, in the female SMP is difficult to distinguish with available reagents. The position of the cell bodies and their projection pattern are similar to those described for the sSP-a/aSP2/fru-aSP2 cluster (Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Accordingly, we hereafter refer to the R47A04 neurons in the SMP region as R47A04aSP2 neurons (Fig. 3A5). Crosses to neurotransmitter GAL4 lines and antibody staining suggest that these neurons are not cholinergic, mostly glutamatergic and partially GABAergic (Fig. 3C–F).

Figure 3. fru-Expressing aSP2 neurons in R47A04-GAL4 control aggression.

(A1–4) Confocal images of the SMP region in male brains expressing R47A04-LexA>nls::GFP (green) and fruGAL4>nls::tdTomato. (A1) 3D render view, and (A2–4) partial Z-stack images of the boxed region in A1. (A5) Schematic of aSP2 neurons in R47A04-GAL4. (B1,2) Confocal images of R47A04>mCD8::GFP in the SMP region of male (B1) and female (B2) brain. (C–E) Confocal images of the SMP region in flies expressing R47A04-LexA>mCD8::GFP (green) and indicated GAL4 lines driving mCD8::RFP (magenta). (F) Confocal images of R47A04-GAL4>mCD8::GFP (green) male brain immunostained with anti-GABA antibody (magenta). (G1,2) Confocal images of male brain containing split-GAL4 intersection between R47A04-AD and fruP1.LexA>LexAop-DBD (R47A04 ∩ Fru) driving UAS-Kir2.1eGFP; G2: magnified image of the boxed region in G1. (H) Raster plots illustrating bouts of lunges (blue) and UWEs (red) in control (no NaChBac) or aSP2-split GAL4>NaChBac fly pairs. (I–L) Average lunging rate (I), fighting frequency (see text) (J), unilateral wing extension rate (K) and the SBPI (L) of flies of the indicated genotypes; “fruP1.LexA” indicates LexA expressed from the fru P1 promoter (Pan et al., 2011). (M) Raster plots illustrating bouts of lunges (blue) and UWEs (red) in control or aSP2-split GAL4-UAS>Kir2.1 fly pairs. (N–Q) Parameters as in (I–L) for flies of the indicated genotypes, except that in (O) the 95th percentile is for single-housed control flies. Scale bars in panel A1, C1, and C2 are 20 μm, A2–4 are 10 μm, B1 and B2 are 50 μm, D is 25 μm. For I–L and N–Q, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed. For L and Q, error bars denote ± S.D.

Next, we determined whether R47A04aSP2 neurons regulate male-male aggression. Since R47A04aSP2 neurons were labeled by both R47A04-LexA and fru-GAL4 (Fig. 3A), we adapted the split GAL4 system (Luan et al., 2006; Pfeiffer et al., 2010) to label them intersectionally. We used the R47A04 CRM to express the GAL4 activation domain (GAL4AD) in R47A04 neurons; for lack of a fru-GAL4-DNA-binding domain (DBD) hemi-driver, we combined fru-LexA (Pan et al., 2011) with LexAop2-DBD to express the GAL4DBD in fruM+ neurons. Using this triple-transgene modified split GAL4 approach, only the aSP2 neurons were labeled (Fig. 3G).

Activation of R47A04aSP2 neurons with NaChBac in group housed flies (in which wing extension predominates over aggression (Wang et al., 2008)) increased both the number of lunges and the fighting frequency (defined as the fraction of flies performing lunges above the 95th percentile rate of non-aggressive control flies), but did not significantly increase or decrease the average frequency of UWE across all flies (Fig. 3H–K). To examine the effect of this manipulation on the relative proportion of aggression vs. UWE, we calculated the SBPI for each fly pair and averaged the value across all pairs. In R47A04aSP2>NaChBac flies, the SBPI was increased to +0.5, vs. −0.3 in BDPG4U>NaChBac controls, indicating a change from social behavior dominated by UWE to that dominated by aggression (Fig. 3L).

Conversely, silencing of R47A04aSP2 neurons with Kir2.1 suppressed both the number of lunges and the fighting frequency (defined as the fraction of flies performing lunges above the 95th percentile rate of single-housed aggressive control flies) but did not affect the frequency of UWE (Fig. 3M–P). This manipulation shifted the SBPI from +0.5 (in controls) to −0.5 (Fig. 3Q), indicating that the proportion of aggression vs. courtship was reversed in favor of the latter. Together, these data demonstrate bidirectional control of male-male social interactions by functional manipulations of R47A04aSP2 neuronal activity. These manipulations did not affect other behaviors including male-female courtship (Fig. S3).

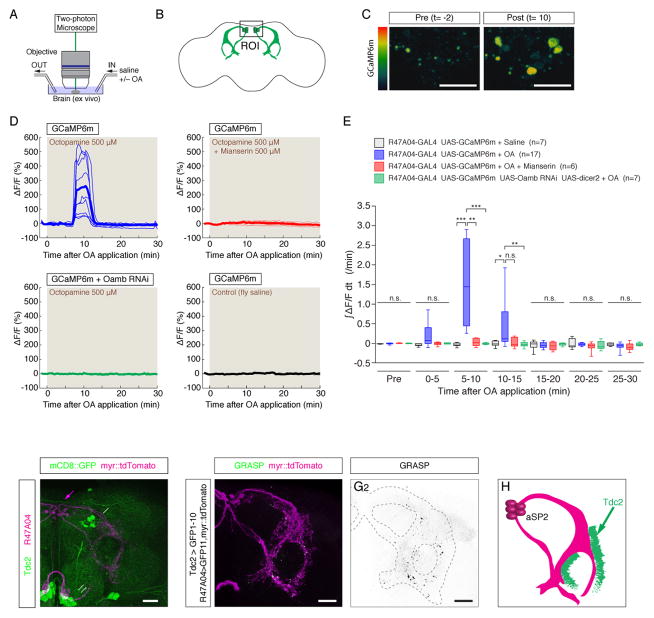

R47A04aSP2 neurons respond to OA in an Oamb-dependent manner

Since our genetic experiments indicated that Oamb acts in R47A04 neurons to control aggression (Fig. 2), we attempted to confirm OAMB expression in R47A04aSP2 neurons by immunostaining. However, we could not detect clear labeling with available antibodies (Kim et al., 2013), possibly due to weak expression. As an alternative approach, therefore, we investigated whether R47A04aSP2 neurons are physiologically responsive to OA, using calcium imaging and two-photon microscopy (2PM). We imaged brain explants expressing a genetically encoded calcium sensor (GCaMP6m; (Chen et al., 2013)) in R47A04 neurons, mounted in a perfusion system (Fig. 4A, B). Bath application of 500 μM OA induced a robust increase in intracellular calcium in R47A04aSP2 neurons (Fig. 4C–E), a response that terminated after ~5 min (likely reflecting GPCR desensitization (Gainetdinov et al., 2004). Importantly, this response was blocked by 500 μM mianserin, an OA receptor antagonist (Fig. 4D, E, red). Interestingly, the calcium increase occurred ~5–10 minutes after OA bath application (Fig. 4D). This may reflect the slow diffusion of OA into the brain explant, the kinetics of activation of second messenger systems that mediate calcium increases in response to Oamb activation, or the involvement of intermediate OA-responsive neurons (Lee et al., 2003; Balfanz et al., 2005; Evans and Maqueira, 2005). However, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Oamb expression (Burke et al., 2012) using R47A04-GAL4 also prevented the OA-evoked Ca2+ increase in aSP2 neurons (Fig. 4D, E, green).

Figure 4. R47A04aSP2 neurons respond to OA.

(A, B) Experimental setup for calcium imaging of R47A04aSP2 neurons in brain explants using 2PM. Brains were perfused with saline or 500 μM OA. (C) Representative images of GCaMP responses during pre-stimulation (Pre (t=−2 min)) and post-stimulation (Post (t=10 min)) in R47A04aSP2 neurons. (D) Responses (%ΔF/F) of R47A04aSP2 neurons to 500μM OA perfusion in brain explants from R47A04-GAL4>UAS-GCaMP6m flies, with or without 500μM mianserin (red line) or UAS-Oamb RNAi (green line). (E) Fold changes in integrated %ΔF/F (∫ΔF/Fdt) during indicated time periods. (F) Confocal image of Tdc2-GAL4>mCD8::GFP (green) and R47A04-LexA>myr::tdTomato in the lateral protocerebral complex. Magenta arrow: cell bodies of R47A04aSP2 neurons, white arrow: OA-ASM, white double arrows: OA-AL and white arrowhead: OA-VL. (G1,2) Native GRASP signals (G1: green and G2: GRASP only) with Tdc2-GAL4>CD4::spGFP1-10 and R47A04-LexA>CD4::spGFP11 and the fibers of R47A04-LexA neurons labeled with LexAop2-myr::tdTomato (G1, magenta). R47A04aSP2 fibers are delineated by dashed line in G2. (H) Schematic of aSP2 neurons with putative input site from Tdc2+ neurons. Scale bars in panel C are 10 μm, and F, G1 and G2 are 20 μm. For E, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed.

Anatomic relationship of R47A04aSP2 neurons to OANs

To determine whether R47A04aSP2 neurons are anatomically positioned to respond to OANs, we directly compared the arborization patterns of R47A04 neurons and OANs labeled by Tdc2-GAL4, using double-labeling with genetic reporters. Analysis of these flies revealed dense projections of Tdc2-GAL4 neurons in the arch and ring regions of the lateral protocerebrum, where R47A04aSP2 neurons arborize (Fig. 4F). To determine whether these fibers are in close proximity, we used the GFP reconstitution across synaptic partners (GRASP) technique (Feinberg et al., 2008; Gordon and Scott, 2009). These experiments revealed reconstituted GFP signals along the ring region in the lateral protocerebrum (Fig. 4G, H). While the presence of GRASP signals does not prove synaptic connectivity (B.D.P. 2014, PhD thesis, Cambridge University), the result shows that neurites of R47A04aSP2 neurons and OANs are in close proximity. Consistent with this, optogenetic stimulation of Tdc2-GAL4 neurons elicited calcium transients in R47A04aSP2 neurons expressing GCaMP6s (not shown); however these responses were variable, perhaps reflecting low levels of evoked OA release.

The Drosophila CNS contains ~100 OANs, divided into ~27 different classes (Busch et al., 2009). In an attempt to identify the subset of OANs that projects onto R47A04aSP2 neurons, we expressed photoactivatable GFP (C3PA-GFP) (Datta et al., 2008; Ruta et al., 2010) in Tdc2-GAL4 neurons and myr::tdTomato in R47A04aSP2 neurons using R47A04-LexA. We targeted 2P photo-activation of C3PA-GFP to Tdc2-GAL4 fibers in the region of the ring neuropil containing R47A04aSP2 fibers, guided by expression of tdTomato (Fig. S4A1, dashed square). These experiments revealed selective C3PA-GFP labeling in several classes of Tdc2+ neurons including ASM, VPM/VUM and AL OANs (Fig. S4A3). VPM/VUM OANs have been implicated in aggression by previous studies (Certel et al., 2007; Zhou and Rao, 2008; Certel et al., 2010). Efforts to silence or activate other OANs identified by PA-GFP labeling using available GAL4 lines yielded negative behavioral results. Nevertheless, these studies together suggest that R47A04aSP2 neurons likely receive input from one or more classes of OANs in vivo.

Interaction between R47A04aSP2 Neurons and Other Aggression-Promoting Neurons

We turned next to the question of how and where the activation of aSP2 neurons promotes aggression. One possibility is that these OARNs might serve as command-like neurons (Bentley and Konishi, 1978) for aggression. However, activation of R47A04aSP2 neurons using red-shifted opsins (Inagaki et al., 2014; Klapoetke et al., 2014) or dTrpA1 (Hamada et al., 2008), which acutely promote spiking (Parisky et al., 2008), did not evoke aggression (data not shown). In contrast activation of aSP2 neurons using NaChBac, which increases neuronal excitability but does not promote spiking (Nitabach et al., 2006; Cao et al., 2013), increased aggression. Together, these data argue against a role for R47A04aSP2 cells as command-like neurons for aggression, and instead support a modulatory influence. To investigate how these OARNs exert this influence, we investigated functional interactions between them and other neuronal populations that can acutely promote aggression (Hoopfer, 2016).

We first investigated interactions with TKFruM neurons, a small (3–4 cells/hemibrain) cluster of FruM+ male-specific neurons that express the neuropeptide Drosophila tachykinin (DTK), and whose conditional activation by dTrpA1 promotes aggression but not courtship (Asahina et al., 2014). To ask whether TKFruM neurons act via R47A04aSP2 neurons, we performed a cellular epistasis experiment in which TKFruM neurons were activated using CsChrimson, while inhibiting R47A04aSP2 neurons using Kir2.1 (Fig. S5A). Optogenetic activation of TKFruM neurons strongly increased lunging, but silencing R47A04aSP2 neurons did not impair this effect (Fig. S5B, C). These data indicate that R47A04aSP2 neurons are not required for the effect of TKFruM neurons to promote aggression, suggesting that they act in parallel with (or upstream of) the latter.

We next investigated possible interactions between R47A04aSP2 neurons and P1 interneurons, another subset of aggression-promoting neurons (Hoopfer et al., 2015; Hoopfer, 2016). P1 cells are a population of sexually dimorphic, FruM+ neurons that were originally identified based on their role in male courtship behavior, and which have been extensively studied in that context (reviewed in (Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013; Auer and Benton, 2016)). Recently, however, it has been shown that transient optogenetic activation of an intersectionally defined subset of these cells (P1a neurons, ~8–10 cells/hemibrain) can also promote aggression, by triggering a persistent internal “π” state (Hoopfer et al., 2015; Anderson, 2016). Importantly, the effect to promote aggression is seen after the offset of photostimulation (PS), i.e., during the π state, while wing-extension is promoted and aggression is suppressed during PS. These inverse effects suggest that P1a neurons may participate in a network controlling the decision between courtship and aggression (Anderson, 2016). It has recently been suggested that the aggression-promoting effect of P1 neuron activation (Hoopfer et al., 2015) is due to a FruM− subset of cells contained within GAL4 lines such as R71G01 (Koganezawa et al., 2016). However intersection experiments using Fru-FLP (Yu et al., 2010) (the same reagent used by Koganezawa et al. (2016) to genetically label FruM+ pC1 cells) indicate that optogenetic activation of a FruM+ subset of R71G01-GAL4 neurons can trigger aggression as well (Fig. S5E–I), consistent with earlier studies using TrpA1 (Hoopfer et al., 2015).

We first investigated whether R47A04aSP2 and P1 neurons might interact anatomically. Direct comparison of P1 and R47A04aSP2 fibers by dual genetic labeling indicated that both populations arborize in the arch and ring region of the lateral protocerebral complex (Fig. 5A). Using GRASP between P1 (R71G01-GAL4 (Pan et al., 2012)) and R47A04 neurons, we observed reconstituted GFP signals within this region (Fig. 5B), indicating close proximity between fibers deriving from these two cell populations. P1 terminals (revealed by syt::GFP expression) were observed in a similar location in the arch region as were aSP2 dendrites revealed by DenMark (Nicolai et al., 2010) (Fig. S4B, C), dorsal to the region where Tdc2 inputs were located in the ring region (Fig. 5C).

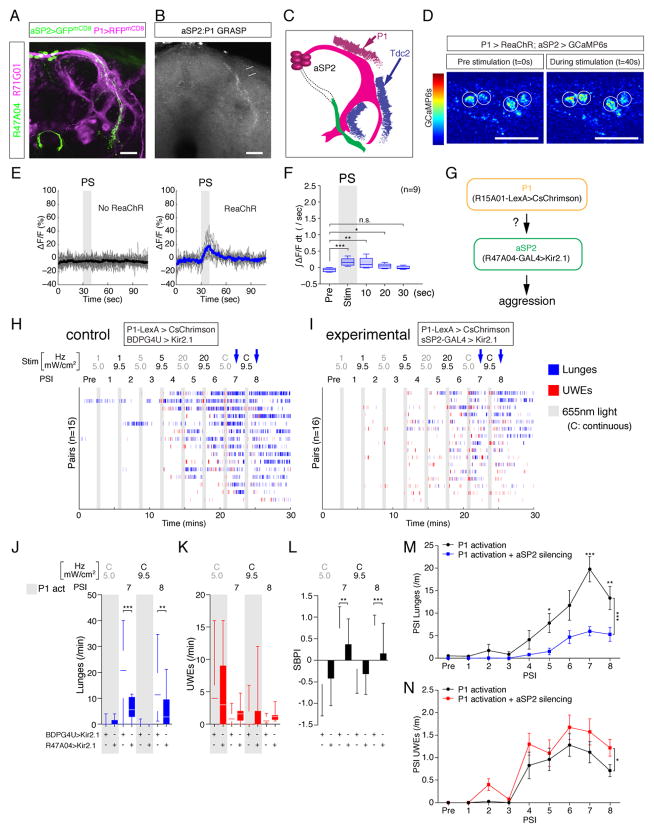

Figure 5. aSP2 neurons are physiological and functional targets of P1 neurons.

(A) Confocal image illustrating close proximity between aSP2 (green) and P1 neurons (magenta) in the lateral protocerebral complex. (B) GRASP signals between P1 and aSP2 neurons. Arrows: arch region. Arrowheads: ring region (see Fig. 3A5). (C) Schematic of aSP2 neurons with putative input sites from Tdc2+ and P1 neurons. Regions labeled with syt::GFP (green) and DenMark (magenta) are depicted. See also Fig. S4B, C. (D) Representative images during pre-stimulation (t=0s) and P1>ReaChR stimulation (t=40s) of GCaMP6s responses (ΔF/F) in aSP2 neurons.. Circles: cell bodies of aSP2 neurons. (E) Responses (%ΔF/F) of aSP2 neurons to P1 stimulation. No ReaChR: control flies lacking UAS-ReaChR. Thick solid lines represent average trace and thin grey lines individual responses. (F) Fold change in integrated ΔF/F (∫ΔF/Fdt) during indicated 10 sec time bins. (G–N) Epistatic relationship between P1 and aSP2 neurons. (G) Experimental design. (H, I) Raster plots of control (H, P1>CsChrimson + BDPG4U>Kir2.1) and experimental (I, P1>CsChrimson + R47A04>Kir2.1) flies. Blocks of frequency and intensity-titrated 30 s photostimulation trials (grey bars, 655 nm) with 2.5 min inter-trial intervals were delivered as indicated. C, continuous stimulation. Blue arrows indicate Post-Stimulation Intervals (PSIs) showing statistically significant differences between experimental and control flies. (J–L), Frequency of lunges (J) and UWEs (K), and SBPI (L) during PSIs showing significant differences. For L, error bars denote ± S.D. (M, N) Frequency of lunges (M) and UWEs (N) for all PSIs. Data points indicate mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant pairwise comparisons, bracket indicates significant difference between curves (*: P<0.05, ***: P<0.001). Scale bars in panel A and B are 20 μm, D are 10 μm. For F and J–L, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed. For M and N, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed.

These anatomical observations prompted us to test whether R47A04aSP2 neurons and P1 neurons are functionally connected. To address this question, we performed all-optical stimulation and recording experiments in whole brain explants using 2PM. We expressed ReaChR (Lin et al., 2013; Inagaki et al., 2014)) in P1 neurons, using R71G01-GAL4, and GCaMP6s in aSP2 neurons using R47A04-LexA. Strikingly, optogenetic activation of P1 neurons evoked a short-latency rise in intracellular free Ca2+ in R47A04aSP2 neurons (Fig. 5D, 5E). This response was initiated during ReaChR stimulation of P1 neurons and persisted for ~20 sec after PS offset (Fig. 5F). Together these data suggest that R47A04aSP2 neurons receive net excitatory input from P1 neurons (but do not distinguish whether this connection is mono- or poly-synaptic). Efforts to demonstrate a reciprocal connection (aSP2→P1) yielded negative results.

These functional imaging experiments raised the question of whether R47A04aSP2 neuronal activity is required for the behavioral effects of P1 activation. To address this question, we performed a genetic epistasis experiment in which P1 neurons were optogenetically activated using R15A01-LexA>CsChrimson, while concomitantly inhibiting R47A04-GAL4 neurons using Kir2.1 (Fig. 5G). Silencing of R47A04 neurons clearly suppressed lunging induced by low or high intensity continuous P1 activation, in comparison to “empty” GAL4>Kir2.1 control flies (Fig. 5H vs. 5I, blue arrows; Fig. 5J, M). UWEs were slightly higher in experimental flies (2-way ANOVA, p<.05; Fig. 5K, N). The SBPI during the post-photostimulation intervals (PSIs) was significantly reduced, relative to controls, by silencing R47A04 neurons (Fig. 5L). Thus, R47A04 neurons are required for the effect of P1 neuron activation to promote male aggressive behavior. This epistatic interaction does not, however, reflect simply a permissive requirement for R47A04 neurons in aggression, since silencing these neurons did not block aggression promoted by activation of TKFruM cells (Fig. S5A–D).

OA modulates the behavioral output of P1 neurons via R47A04 cells

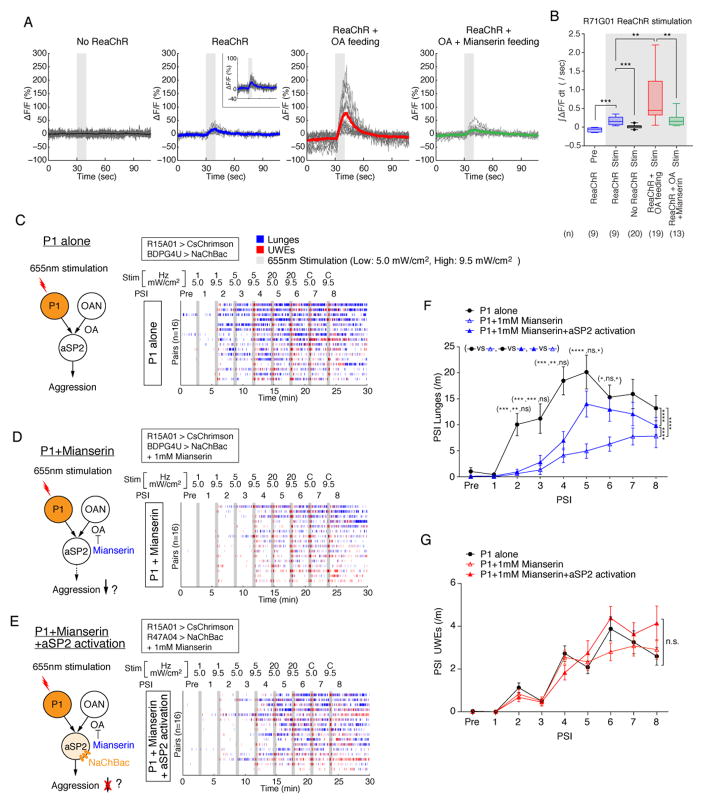

We next investigated 3-way interactions between P1 neurons, OA and R47A04aSP2 neurons. Since R47A04aSP2 neurons responded ex vivo to either bath-applied OA (Fig. 4E) or to P1 stimulation (Fig. 5F), we first asked whether increased OAergic signaling in vivo might enhance R47A04aSP2 Ca2+ responses to P1 activation. To this end, we fed flies with 500 μM OA 24 hr prior to imaging experiments. Indeed, explants from OA-fed flies showed a dramatic enhancement of R47A04aSP2>GCaMP6s responses evoked by P1 stimulation using ReaChR (Fig. 6A, 6B, red vs. blue). Importantly co-feeding of flies with 500 μM mianserin, an OAR antagonist, attenuated this effect (Fig. 6A, 6B, green vs. red). Thus elevating OA in vivo can enhance the ability of P1 neurons to activate R47A04aSP2 neurons ex vivo, consistent with the idea that these two influences are convergent (Fig. 5C).

Figure 6. Convergent activation of R47A04aSP2 neurons by P1 activation and OA.

(A, B) OAergic modulation of the calcium response of aSP2 neurons to P1 optogenetic activation. All flies contained R71G01-GAL4>ReaChR and R47A04-LexA>GCaMP6s unless otherwise indicated. (A) Time courses of average (thick line) and individual (thin lines) responses (%ΔF/F). OA or mianserin feeding (500 μM each) are indicated. The data for No ReaChR and ReaChR are reprinted from Fig. 5 using the same y-axis scale, to facilitate visual comparisons. Statistical analyses (B and Fig. 5F) were performed using all pooled data and P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons with all conditions using the Bonferroni correction. (B) Fold change in integrated ΔF/F (∫ΔF/Fdt) during light stimulation period. (C–G) Experiment to test epistatic interactions between P1 stimulation and endogenous OA signaling with or without aSP2 neuronal activation. (C–E) (Left) experimental design, drug treatment and genotypes for each condition. (Right) raster plots showing bouts of lunges (blue) and UWEs (red) evoked by P1 activation without (C) or with (D, E) 1 mM mianserin feeding, together with (E) or without (C, D) NaChBac-mediated aSP2 activation.. Blocks of frequency (1 Hz, 5 Hz, 20 Hz and Continuous (C)) and intensity (5.0 mW/cm2, 9.5 mW/cm2)-titrated 30 s photostimulation (grey bars, 655 nm) with 2.5 min inter-trial intervals were delivered as indicated above raster plots. (F, G) Frequency of lunges (F) and UWEs (G). Data points indicate mean ± S.E.M. For bar graphs and SBPI scores see Figure S6A–C. For F–G, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that 1) P1 influences on social behavior might be biased toward aggression by OA; and 2) R47A04aSP2 neurons might mediate this biasing influence of OA. To test this hypothesis, we first asked whether the effect of P1 stimulation to promote aggression is reduced by inhibition of endogenous OA signaling, and if so whether this reduction can be overcome by constitutively activating R47A04 neurons (Fig. 6C–E). Indeed, treatment with mianserin suppressed lunging under optimal conditions of P1 photostimulation (Fig. 6C, D, F and Fig. S6A), but had no effect on UWE (Fig. 6G and Fig. S6B). This effect was not due to any influence on locomotor activity (Fig. S6D). Importantly, the effect of mianserin to inhibit P1-induced aggression at high PS frequencies was largely rescued by concomitant activation of R47A04 neurons using NaChBac (Fig. 6E, F and Fig. S6A, light vs. dark blue bars). Thus, inhibiting endogenous OAergic signaling using mianserin reduced the SBPI evoked by P1 activation, and this effect could be partially rescued by activation of R47A04 neurons (Fig. S6C).

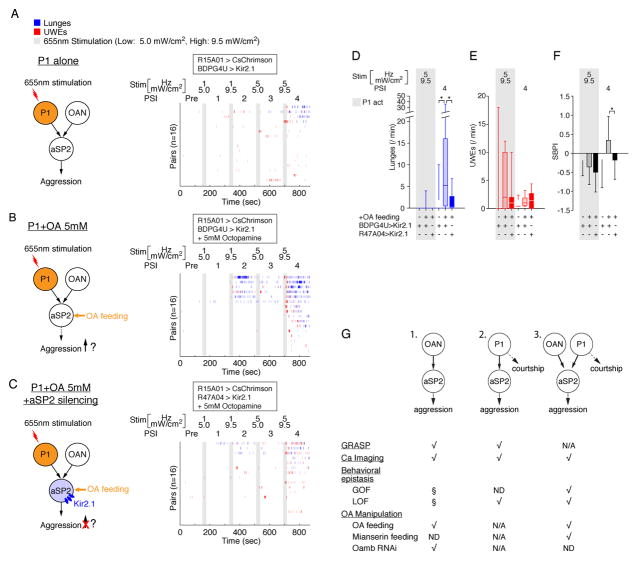

Finally, we addressed the question of whether, conversely, OA feeding enhanced the effect of P1 stimulation to promote aggression, and if so whether this effect is dependent upon R47A04 neuronal activity (Fig. 7A–C). Indeed, OA feeding strongly increased the number of lunges following high intensity P1 photostimulation (5 Hz, 9.5 mW/cm2) in control BDPG4>UAS-Kir2.1 flies (Fig. 7A, B, blue rasters; 7D, white vs. light blue bars and Fig. S7A, D). Moreover, the effect of OA feeding was overridden by silencing R47A04 neurons (Fig. 7B vs. C, blue rasters; 7D, light vs. dark blue bars; Fig. S7A, D). Thus, OA feeding increased the SBPI following P1 photoactivation (aggression>courtship), and this effect was reversed by silencing R47A04 neurons (Fig. 7F and Fig. S7C). There was no significant change in locomotor activity associated with these manipulations (Fig. S7F). There was also no statistically significant effect on P1-evoked UWEs caused by OA feeding, in either male pairs (Fig. 7B, red rasters; 7E and Fig. S7B, E) or in solitary flies (Fig. S7G, H), or any effect of R47A04 silencing (Fig. 7C, E and Fig. S7B, E). Taken together, the data of Figs. 6 and 7 indicate that aggression induced by P1 activation is sensitive to pharmacological loss- or gain-of-function manipulations of endogenous OA signaling, and that these effects can be overridden by activating or inhibiting R47A04aSP2 neurons, respectively.

Figure 7. OAergic modulation enhances P1-stimulated aggression in an aSP2-dependent manner.

(A–F) Optogenetic activation of P1 neurons was performed without (A) or with (B, C) 5 mM OA feeding, with (C) or without (A, B) silencing of R47A04 neurons. (A–C) (Left), experimental design, drug treatments and genotypes. (Right), raster plots showing bouts of lunges (blue) and UWEs (red) in fly pairs subjected to P1 activation alone (A), P1 activation + 5mM OA feeding (B) or P1 activation +5 mM OA feeding + aSP2 silencing (C). Blocks of frequency (1 Hz, 5 Hz) and intensity (5.0 mW/cm2, 9.5 mW/cm2) titrated 30 s photostimulation trials (grey bars, 655 nm) with 2.5 min inter-trial intervals were delivered as indicated (right). Aggression in P1-stimulated flies (A) was low in this experiment, possibly due to leakage expression of BDPG4U>Kir2.1 in the control genetic background. (D–F) Frequency of lunges (D), UWEs (E) and SBPI (F). For clarity, only PSIs showing statistically significant differences are illustrated; data for all PSI intervals are shown in Figure S7A–C. For F, error bars denote ± S.D. (G) Summary of experiments showing the interaction between OA neurons, P1 neurons and aSP2 neurons. “√” indicates experiments performed; “N/A,” Not Applicable; “ND,” Not Done. “§” indicates that experiments were part of the design illustrated in G3 (Figs. 6 and 7). Arrows in illustrations are not meant to imply monosynaptic connectivity. It is uncertain whether the behavioral, physiological and anatomical interactions between P1 and aSP2 cells documented here (G2, G3) are all mediated by the same subset of P1 neurons. For D–F, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were performed.

DISCUSSION

A rich behavioral literature has implicated OA in the control of invertebrate aggression, although the direction of its effects differs between species. Classic studies in lobsters have shown that injection of OA into the hemolymph promotes a subordinate-like posture, while injection of serotonin (5HT) produces a dominant-like posture (Livingstone et al., 1980; Huber et al., 1997). In contrast, hemolymph injections of OA in crickets restore aggressiveness to subordinated animals, mimicking the arousing effects of episodes of free flight (Adamo et al., 1995; Stevenson et al., 2005). OA has also been suggested to play a role in aggressive motivation restored to defeated crickets by residency in a shelter (Rillich et al., 2011). In Drosophila, null mutations of TβH (Monastirioti et al., 1996) strongly suppressed aggressiveness (Baier et al., 2002), suggesting a positive-acting role for OA in flies as in crickets. Interestingly, intra-hypothalamic infusion of NE in mammals can also enhance aggression (Barrett et al., 1990). However, little is known about the neurons on which these amines act directly to influence aggression, in any organism.

Here we have applied a novel, unbiased approach to identify OARNs relevant to aggression in Drosophila. Importantly this screen was based not on mutations in OAR genes, but rather upon genetic silencing of neurons that express GAL4 under the control of different OAR gene cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) (Pfeiffer et al., 2008). This screen was agnostic with respect to which OAR gene is involved, or in which neurons that OAR is expressed. It yielded a small population of male-specific, FruM+ OA-sensitive neurons, called aSP2, the activity of which is required for normal levels of aggressiveness. No significant change in UWEs (male-male courtship) was observed when these neurons were activated or silenced. Nevertheless, neuronal silencing in the parental R47A04-GAL4 line increased male-male courtship, perhaps reflecting an inhibitory role for non-aSP2 neurons in that line. Therefore, while we cannot completely exclude a role for aSP2 neurons to suppress male-male courtship, the evidence does not strongly support it.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that R47A04aSP2 neurons are indeed OA-responsive, likely via OAMB. First, these neurons are labeled by a CRM from the Oamb gene. Second, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Oamb in R47A04 neurons reduced aggression, phenocopying the effects of an Oamb null allele. (However, knockdown using the split-GAL4 R47A04aSP2 driver only yielded a trend to reduced aggression that did not reach significance (not shown), perhaps reflecting a floor effect in this assay). Third, over-expression of Oamb cDNAs in these neurons using R47A04-GAL4 rescued the Oamb null mutant, and enhanced the effect of OA feeding to promote aggression. Fourth, R47A04aSP2 neurons were activated by bath-applied OA in brain explants, and this effect was also blocked by RNAi-mediated knockdown of Oamb. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that aSP2 neurons respond directly to OA to mediate its effects on aggression, although they do not exclude a role for other OA-responsive non-aSP2 neurons in line R47A04. While we have been unable to definitively establish which of the 27 different classes of OANs in Drosophila (Busch et al., 2009) provide functional OA input to aSP2 cells, some candidate OA neurons labeled in our retrograde PA-GFP experiments (VUM and VPM) have previously been implicated in aggression ((Zhou and Rao, 2008; Certel et al., 2010).

In Drosophila OA, like NE in vertebrates, is thought to promote arousal reviewed in (Roeder, 1999; Roeder, 2005; Nall and Sehgal, 2014)). Consistent with such a function, OAergic fibers are broadly distributed across the entire Drosophila CNS (Monastirioti et al., 1995), as are NE fibers in vertebrates (Schwarz et al., 2015; Espana et al., 2016). Thus OARNs could enhance aggression by increasing arousal, and there is evidence for such a function in crickets (Stevenson et al., 2000). However, manipulations of R47A04aSP2 neurons that increased or decreased aggression did not affect locomotion, circadian activity or sleep. This suggests that these neurons influence aggression directly and specifically, rather than by increasing generalized arousal. Other classes of OARNs not investigated in this study have been implicated in sleep-wake arousal (Crocker and Sehgal, 2008).

Does OA promote aggression in a permissive or instructive manner? While it is clear that OA synthesis and release are required for aggression in Drosophila ((Baier et al., 2002; Hoyer et al., 2008; Zhou and Rao, 2008), whether increasing OA suffices to promote aggression is less clear. It was reported that NaChBac-mediated activation of Tdc2-GAL4 neurons enhanced aggression (Zhou and Rao, 2008), but in our hands neither this manipulation, nor activation of Tdc2 neurons using dTrpA1 or Chrimson, yielded consistent effects. (To the contrary, (Certel et al., 2010) reported that activating Tdc2-GAL4 neurons using dTrpA1 increased male-male courtship.) Thus, while OA is essential for normal levels of aggression, it is not clear whether it plays an instructive role to promote this behavior.

aSP2 neurons receive input from P1 neurons as well as OANs

In principle, OARNs could act directly in command-like neurons that mediate aggression, or rather in cells that play a modulatory role. We found that aggression was increased by tonically enhancing the excitability of R47A04aSP2 neurons using NaChBac (Cao et al., 2013), but not by phasically activating them optogenetically, arguing against a command-like function. Furthermore, the influence of TKFruM neurons (Asahina et al., 2014), which do promote aggression when phasically activated (Fig. S5A–C), was not dependent on the activity of R47A04aSP2 neurons, indicating that the latter are not functionally downstream of the former. Together, these data argue against a role for R47A04aSP2 cells as command-like neurons, or as direct outputs of command neurons, for aggression. Rather, these cells exert a modulatory influence on agonistic behavior.

In searching for neurons that may interact with R47A04aSP2 cells in their modulatory capacity, we identified P1 neurons, a FruM+ population of ~20 neurons/hemibrain that controls male courtship (reviewed in (Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014; Auer and Benton, 2016)), but which can also promote aggression when activated (Hoopfer et al., 2015). It has been argued (Koganezawa et al., 2016) that this aggression-promoting effect is due to a subset of FruM− neurons in the GAL4 line used in our studies, R71G01-GAL4 (Pan et al., 2012). However, we show here that conditional expression of FLP-ON Chrimson in a subset of neurons within the R71G01-GAL4 population using Fru-FLP ((Yu et al., 2010); the same reagent used by Koganezawa et al (2016) to mark FruM+ pC1 neurons) yields optogenetically-stimulated aggression. Nevertheless, these data do not exclude that the aggression-promoting neurons in the P1 cluster expressed Fru-FLP only transiently during development, nor do they exclude the possibility that different subpopulations of neurons within line R71G01 control courtship vs. aggression; further studies will be required to resolve these issues.

The P1 cluster is known to project to downstream cells that are specific for courtship (von Philipsborn et al., 2011). The present study provides the first evidence that cells in this cluster also functionally activate (and physically contact) aggression-specific neurons. However due to limitations of the genetic reagents employed, it is not certain that the behavioral, physiological and anatomical interactions with aSP2 cells demonstrated here are all mediated by the same subset of neurons in the P1 cluster. With this caveat in mind, these data suggest that aSP2 neurons are functionally downstream of both a subset(s) of P1 neurons, as well as of OA neurons.

Our evidence demonstrates a functional interaction between OA and P1 inputs to aSP2 neurons. Feeding flies OA potentiated the activation of R47A04aSP2 neurons by P1 neuron stimulation, in brain explants. Furthermore, activation of aggression by P1 stimulation was enhanced and suppressed by pharmacologically increasing or decreasing OA signaling, respectively. While we cannot exclude some off-target effects of the drugs, or an action on non-aSP2 neurons expressing OARs, these pharmacologic effects were overridden by opposite-direction genetic manipulations of R47A04aSP2 neuronal activity. Whether P1 neurons and OANs normally activate aSP2 neurons in vivo, simultaneously or sequentially, is not yet clear. Nevertheless it is striking that P1 and Tdc2 putative inputs occupy adjacent regions of aSP2 dendrites. Taken together, these findings suggest that aSP2 cells may serve as a node through which OA can bias output from a multifunctional social behavior network involving P1 neurons, in a manner that favors aggression (Certel et al., 2007; Certel et al., 2010). However aSP2 neurons themselves do not appear to control directly the choice between mating and fighting.

Male-specific cuticular hydrocarbons such as 7-tricosene (7-T) are known to be required for aggression (Fernandez et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, it has recently been shown that gustatory neurons expressing Gr32a, which encodes a putative 7-T receptor (Lacaille et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011), innervate OANs in the SEZ; these OANs are activated by 7-T in a Gr32a-dependent manner (Andrews et al., 2014). SEZ-innervating OANs include the VPM/VUM subsets seen in our PA-GFP retrograde labeling experiments. These data raise the possibility that R47A04aSP2 neurons might be targets of VMP/VUM OANs activated by 7-T. If so, then they could provide a potential link between the influence of male-specific pheromones, OA and central aggression circuitry.

Studies of NE neurons in vertebrates have led to a prevailing view that this neuromodulator is released in a diffuse, “sprinkler system”-like manner to control brain-wide states like arousal (Foote and Morrison, 1987; Espana et al., 2016). Recent studies in Drosophila indicate that the broad, brain-wide distribution of OAergic fibers (Monastirioti et al., 1995; Sinakevitch and Strausfeld, 2006) reflects the superposition of close to 30 anatomically distinct subclasses of OANs (Busch et al., 2009). The data presented here reveal a high level of circuit-specificity for OARNs that mediate the effects of OA on aggression, mirroring the anatomical and functional specificity of OANs reported to control this behavior (Zhou and Rao, 2008; Certel et al., 2010; Andrews et al., 2014). If this anatomical logic is conserved ((Kebschull et al., 2016); but see (Schwarz et al., 2015)), then such circuit-specificity may underlie the actions of NE in mammals to a greater extent than is generally assumed.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and request for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, David J Anderson (wuwei@caltech.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Fly Strains

A list of the full genotypes for the flies used in each figure is in Table S1.

The following stocks were kindly provided: wild-type Canton S (Hoyer et al., 2008) was from M. Heisenberg; fruGAL4 (Stockinger et al., 2005) was from B. Dickson (Janelia Research Campus); fruP1.LexA (Mellert et al., 2010) was from B. Baker (Janelia Research Campus); Oamb286 (Lee et al., 2003) was from K. A. Han (University of Texas at El Paso); 20XUAS-IVS-GCaMP6m and 13XlexAop2-IVS-GCaMP6s (Chen et al., 2013) were from D. Kim (Janelia Research Campus). 13XlexAop2-CsChrimson::Venus (attP40) was from V. Jayaraman (Janelia Research Campus). UAS-CD4::spGFP1-10 and LexAop-CD4::spGFP11 (Gordon and Scott, 2009) were from K. Scott (University of California, Berkeley). UAS-C3PA-GFP (Ruta et al., 2010) was from R. Axel (Columbia University).

The following strains were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University); UAS-eGFP::Kir2.1 (#6595), tub-GAL80ts (#7017, #7018, #7019, 7108), UAS-NaChBac::eGFP (#9466), Tdc2-GAL4 (#9313), Gad1-GAL4 (#51630), ChAT-GAL4 (#60317), vGlut-GAL4 (#60312).

UAS-Oamb RNAi (#2861), UAS-dicer2 (#60013, #60014) and w1118 (#60000) were obtained from Vienna Drosophila Stock Center (VDRC, www.vdrc.at).

Otd-nls::FLPo (attP40), Tk-GAL41 and UAS-ReaChR (VK00005) were produced in the Anderson lab (Asahina et al., 2014; Inagaki et al., 2014).

GAL4 lines used for the screening are available from Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University).

pBDPGAL4U (attP2), R47A04-LexA (R47A04-nls::LexA::p65) (attP18, attP40 and attP2), R47A04-AD (R47A04-p65ADZp) (attP40), R71G01-GAL4 (attP2), R15A01-LexA (attP2), R15A01-AD (R15A01-p65ADZp) (attP40), R71G01-DBD (R71G01-ZpGAL4DBD) (attP2), pJFRC2-10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP (attP2), pJFRC15-13XlexAop2-mCD8::GFP (su(Hw)attP8), pJFRC21-10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::RFP (attP18), pJFRC48-13XlexAop2-IVS-myr::tdTomato (attP18), pJFRC105-10XUAS-IVS-nls::tdTomato (VK00022), pJFRC107-13XlexAop2-IVS-nls::GFP (VK00040), 20XUAS-IVS-Syn21-Chrimson::tdTomato-3.1 (su(Hw)attP5), pJFRC67-3XUAS-syt::GFP (attP18) and pJFRC118-10XUAS-DenMark (Nicolai et al., 2010) (attP40) were produced in the Rubin lab (Pfeiffer et al., 2008; Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Seelig and Jayaraman, 2013; Inagaki et al., 2014; Hoopfer et al., 2015).

Construction of Transgenic Animals

Acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method was used to isolate total RNA from Bloomington #2057 strain as described previously using TRI Reagent Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Acid-Phenol: Chloroform, pH4.5 (with IAA, 125:24:1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Drosophila cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with Oligo(dT)20 Primer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). All PCR reactions were performed using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). After PCR amplification, all DNA fragments were verified by DNA sequencing (Laragen, Inc., Culver City, CA). Completed vectors were inserted into indicated genomic sites using PhiC31 integrase-mediated transgenesis (Genetic Services, Inc., Sudbury, MA) (BestGene, Inc., Chino Hills, CA).

UAS-Oamb AS and UAS-Oamb K3 were created as follows.

First, Gateway Reading Frame Cassette A (RfA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was cloned into pJFRC-MUH ((Pfeiffer et al., 2010); Addgene #26213).

Oamb-AS and Oamb-K3 cDNA was amplified from cDNA using following primers.

attB1 Oamb-AS/K3 (5′): 5′-AAAAAGCAGGCTCAAAATGAATGAAACAGAG-3′

attB2 Oamb-AS (3′): 5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTTCACCTGGGGTCGTTGCT-3′

attB2 Oamb-K3 (3′): 5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTTCAGCTGAAGTCCACGCC-3′

After a first PCR reaction, a second PCR reaction was performed to install the attB sequence with following adapter primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

attB1 adapter: GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT-3′

attB2 adapter: 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT-3′

The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into pDONR221 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with BP Clonase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and cloned into pJFRC-MUH-RfA with LR Clonase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

The eyeless-nls::FLPo construct was created as follows:

An nls::FLPo fragment was amplified using PCR with primers including the nuclear localization signal (nls, ATGGCCCCCAAGAAGAAGCGCAAGGTG) derived from the SV40 large T-antigen, and replaced GAL4 coding sequence and yeast terminator of pBPGUw ((Pfeiffer et al., 2008); Addgene #17575) at Hind III/Hind III site, consequently generating pBPGUw-nls::FLPo.

The eyeless enhancer fragment was amplified and cloned from the Drosophila genomic DNA. The genomic DNA was isolated by standard molecular biological method. Briefly, whole fly bodies were frozen in liquid nitrogen and crushed with a pestle. After incubating in the digestion buffer including 0.5% SDS and 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K at 50 °C for 12 hours, the genomic DNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

The following primers were used to clone the genomic fragment including previously characterized Drosophila eyeless promoter (Newsome et al., 2000).

eyeless (5)′: 5′-CTGTTACATACTGTTCAACG-3′

eyeless (3′): 5′-AAAAGGCTAAATGGGCACAC-3′

The amplified fragment was cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO and cloned into pBPGUw-nls::FLPo with LR Clonase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

pMUH-10XUAS-frt-eGFP::Kir2.1-stop-frt-mCherryFP and pMUH-10XUAS-frt-mCherryFP-stop-frt-eGFP::Kir2.1 were generated as follows:

FRT site was added by PCR using primers containing FRT site sequence (GAAGTTCCTATTCCGAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAGTATAGGAACTTC).

eGFP::Kir2.1 (Baines et al., 2001), mCherryFP (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and SV40 polyA sequence from pMUH ((Pfeiffer et al., 2010); Addgene #26213) were amplified by PCR and cloned into pBluescript II. After sequencing, the fragments were cloned into

pJFRC-MUH ((Pfeiffer et al., 2010); Addgene #26213) using NotI.

8XLexAop2-ZpGAL4DBD was generated as follows.

Drosophila codon optimized ZpGAL4 DNA-binding domain was PCR amplified from pBPZpGAL4DBDUw and cloned 5′-XhoI to 3′-XbaI into pJFRC18 (Pfeiffer et al., 2010).

pJFRC58-13XlexAop2-frt-myr::tdTomato-SV40-frt-eGFP::Kir2.1 was generated as follows.

A triple ligation was performed as follows: A 5′-BglII to 3′-XhoI Flpd-OUT cassette (Nern et al., 2011) containing a N-myristoylation fusion to Drosophila codon optimized tdTomato (Pfeiffer et al., 2010) was cloned together with a 5′-SalI to 3′-AvrII eGFP::Kir2.1 transgene into cohesive 5′-BglII to 3′-XbaI sites of pJFRC15-13XlexAop (Pfeiffer et al., 2010).

Construction of 20XUAS-frt-TopHAT2-frt-Syn21-Chrimson::tdTomato3.1 was a multiple step. First, Chrimson was PCR amplified as a 5′-XhoI to 3′-BamHI open reading frame from ChR88 template DNA (gift of Ed Boyden; Klapoetke et al., 2014) to include a Syn21 translational enhancer (Pfeiffer et al., 2012) and a Kir2.1 membrane trafficking signal (Gradinaru et al., 2010) as a N-terminal fusion to PCR amplified 5′-BamHI to 3′-XbaI Drosophila codon-optimized tdTomato containing an ER export signal (Gradinaru et al., 2008; Pfeiffer et al., 2010) into pJFRC2-10XUAS-IVS (Pfeiffer et al., 2010) generating 10X-IVS-Syn21-Chrimson::tdTomato-3.1. Next the Chrimson::tdTomato fusion was liberated as a 5′-XhoI to 3′-XbaI fragment and included in a triple ligation with a 5′ - BglII to 3′ -XhoI Flpd-OUT Cassette (Nern et al., 2011) containing a N-myristoylation fusion to Drosophila codon-optimized Top7 protein (Boschek et al., 2009), embedded with seven copies of a hemagglutinin (HA; YPYDVPDYA) epitope tag separated by Glycine linkers into 5′ - BglII to 3′ - XbaI sites of pJFRC7-20XUAS (Pfeiffer et al., 2010) to generate 20XUAS-frt-TopHAT2-frt-Syn21-Chrimson::tdTomato-3.1.

Aggression Assays

Temperature and humidity of the room for behavioral assays was set to ~25°C and ~50%, respectively.

Flies were maintained at 9AM: 9PM Light: Dark cycle. Aggression assays were performed during two activity peaks between 7 a.m. and 11 a.m. or 7 p.m. and 11 p.m.

For male-male aggression assays in figures 1, 2, S1 and S2, we used double chambers described previously (Hoyer et al., 2008; Dankert et al., 2009). Each arena contains a food area, consisting of apple juice/sucrose-agarose food (2.5% (w/v) sucrose and 2.25% (w/v) agarose in apple juice), surrounded by 1% agarose area (Figure 1C). The arenas were illuminated with a ring light or LED light strips (Flexible LED Strips, The LED Light, Inc., Carson City, NV).

For male-male aggression assays in figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, S5, S6 and S7, the “8-well” acrylic chamber (16 mm diameter × 10 mm height) was used as described previously (Inagaki et al., 2014). The floor of the arenas was composed of clear acrylic covered with a uniform layer of apple juice/sucrose-agarose food. IR backlighting (855 nm, SOBL-6x4-850, SmartVision Lights, Muskegon, MI) was used for illumination from beneath the arena.

For both chamber setups, the walls of the chamber were coated with Insect-a-Slip (Bioquip Products Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA) and the clear top plates were coated with Sigmacote (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to prevent flies from walking on these surfaces. Flies were introduced into the aggression chambers by gentle aspiration using a mouth pipette and were allowed to acclimate to the chamber for 1 to 2 min before the recording. Flies with physical damage during the introduction into the chambers were excluded from analysis. For gain-of-function experiments (Fig. 1F, 2A–D, 3M–Q and S1E–G), group-housed flies were used to suppress baseline aggression in controls, while single-housed flies were used to elevate baseline aggression for loss-of-function experiments (Fig. 1E, 2E, 3H–L, S1B–D and S2B, D–E) (Wang et al., 2008).

METHODS DETAILS

Genetic Manipulation of Neuronal Activity Using Ion Channels

To induce the expression of effectors, tub-GAL80ts was combined with UAS-eGFP::Kir2.1 or UAS-NaChBac::eGFP. Flies were reared and collected on the day of eclosion and single-housed (Kir2.1) or group-housed (~15 flies/vial, NaChBac) on Caltech standard fly medium for 3–5 days at 18°C, then the temperature was shifted to 30°C for 2 days prior to the behavioral assay. Flies were moved to 25°C to acclimate to the temperature 2 hrs prior to the behavioral assays.

Optogenetic Activation

The setup used for optogenetic activation was described previously (Inagaki et al., 2014). Briefly, experiments were performed with “8 well” chambers with IR backlight. 655 nm 10 mm Square LED (Luxeon Star LEDs Quadica Developments Inc., Brantford, Canada) was used for photostimulation (PS). Light intensity was measured at the location of the behavior chambers with a photodiode power sensor (S130VC, Tholabs, Newton, NJ). The stimulation protocols for each experiment are described in the figures and figure legends. Flies were raised at 25°C on Caltech standard fly media, collected on the day of eclosion and group-housed in the dark for 5–7 days on Caltech standard fly media containing 0.4 mM all trans-Retinal (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Drug feeding

Octopamine and mianserin feeding were performed essentially as previously described (Inagaki et al., 2012). 24 hr prior to the experiment, flies were transferred to a vial containing a piece of filter paper soaked with 500 μl of 100 mM sucrose solution with indicated concentration of octopamine or mianserin. For optogenetic experiments, the drug solution were supplemented with 0.4 mM all trans-Retinal (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Locomotor Activity Analysis

Analysis of locomotor activity was performed as described previously (Joiner et al., 2006). Flies were kept on 12 hr light: dark cycle at 25°C. Flies were placed in 5 mm × 65 mm tubes containing 5% sucrose and 2% agarose, allowed to acclimate to the tube for at least 24 hr. Locomotor activity was measured using the DAM2 Drosophila Activity Monitor (TriKinetics Inc., Waltham, MA) with 1 min bin. Sleep was defined as a 5 min bout of inactivity as described previously (Shaw et al., 2000). Data were analyzed using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and Prism5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Whole fly brains or ventral nerve cords were dissected in PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 2 hr at 4°C. For anti-GABA antibody, fly brains were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 2 hr at 4°C. After fixation, all procedures were performed at 4°C. After brief washing with PBS/0.05% Triton X-100, samples were incubated with PBS/2% Triton X-100 for 45 min, followed by 2 hr incubation in blocking solution (PBS/10% normal goat serum/1% Blocking Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI). Primary antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution, and samples were incubated in the primary antibody solution for 2 days. Samples were washed in PBS/0.05% Triton X-100 (1 hr × 5 times). Secondary antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution, and samples were incubated in the secondary antibody solution for 2 days. Following five 1 hr washing with PBS/0.05% Triton X-100, sample were mounted on slide glass in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Confocal serial optical sections were obtained either with a Zeiss LSM510 Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) or a Fluoview FV1000 Confocal Microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2012) and Fluorender software (Wan et al., 2009) was used to create z-stack images.

The antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000, A11122, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), mouse anti-GFP (clone 3E6, 1:1,000, A11120, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), rabbit anti-DsRed (1:1,000, #632496, Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), mouse nc82 (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), rabbit anti-GABA (1:10,000, A2052, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000, A-11001, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1,000, A-11004, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1,000, A-21050, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000, A-11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000, A-11011, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1,000, A-21070, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Calcium Imaging

Brains were dissected from male flies, affixed to the bottom of the 35 mm cell culture dish (#353001, Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA) and immersed in fly saline (108 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 8.2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). 40x/0.80-NA water-immersion objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for imaging.

For OA perfusion experiments, after 2 min image acquisition for base line calcium signals, fly saline or 500 μM OA/fly saline was delivered from the inlet glass capillary connected to a silicon tube until the end of image acquisition. The silicon tube was connected to 50 ml syringe filled with either fly saline or 500 μM OA/fly saline. Flow rate of the solution was controlled using an adjustable flow regulator (Dial-A-Flo, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) as a rate of 250 ml/hr. During fly saline or OA/fly saline was delivered, the solution was removed through the outlet glass capillary, connected to an aspirator. The outlet glass capillary was made as follows. One end of a glass capillary was burned with a gas burner, closed and sent a rapid airflow from the other end, connected to a 10 ml syringe to make a small hole at the side of the capillary, which allowed a gentle aspiration of fluid. Calcium imaging was performed on an Ultima two-photon laser-scanning microscope (Bruker, Billerica, MA). Images were collected from multiple focal planes and captured images every 30 sec. Fluorender software (Wan et al., 2009) was used to create 4D time-lapse images. The average signal before OA perfusion was used as F0 to calculate the ΔF/F0 using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2012). The integral of ΔF/F0 during the indicated time periods, ∫ ΔF/F0, was calculated using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Calcium imaging with optogenetic activation was performed essentially as described in Inagaki et al., (2014). An amber (590 nm) fiber-coupled LED (M590F1, Tholabs, Newton, NJ) with 589/10 nm band-pass filter (Edmund optics, Barrington, NJ) was used for a light source to activate ReaChR. A 200 μm core multimode optic fiber (FT200EMT, Tholabs, Newton, NJ) was used to deliver the light. After 30 sec image acquisition for base line calcium signals, 10 Hz light stimulation was delivered for 10 sec. The average signal before photostimulation was used as F0 to calculate the ΔF/F0 using Fiji software(Schindelin et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2012). The integral of ΔF/F0 during the indicated time periods, ∫ ΔF/F0, was calculated using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Labeling Neurons with Photoactivation

Photoactivation experiment was performed on an Ultima two-photon laser-scanning microscope (Bruker, Billerica, MA). To photoactivate subsets of OAergic neurons, we used flies carrying Tdc2-GAL4, UAS-C3PA-GFP (Ruta et al., 2010), R47A04-nls::LexA and LexAop2-myr::tdTomato. Brains were dissected and affixed to the bottom of the 35 mm cell culture dish (#353001, Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA) and immersed in fly saline (108 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 8.2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). Pre-photoactivation brain images were obtained at 930 nm. myr::tdTomato signals of R47A01aSP2 neurons were used to define the three-dimensional region of photoactivation. The defined region of photoactivation was photoactivated by two cycles of exposure (8 scans × 15 repeats per cycle) to 710 nm laser. To allow diffusion of the photoactivated fluorophore into cell bodies, 10 min interval were given between two photoactivation periods and samples were incubated for 20 min after photoactivation cycles. Images were obtained with 512 × 512 resolution. Three-dimensional images were reconstructed using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2012).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Fly tracking and Behavior Classification

For double chamber setups, a commercial color video CCD camera (HandyCam DCR-HC36 or DCR-HC38, 640 × 480 pixels/frame, 30 frames/s, Sony, Tokyo, Japan) was used. The cameras was connected to a personal computer via IEEE 1394 interface and recorded using Windows Media Encoder with Windows Media Video 9 (WMV9) codec for compressing movie files. Number of lunges was counted by CADABRA software (Dankert et al., 2009).

For 8 well chamber setups, a commercial CCD camera (Point Grey Flea3 1.3MP Mono USB3.0, FL3-U3-13Y3M-C, 1280 × 1024 pixels/frame, 150 frames/s, FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR) was used to record at a frame rate of 30 Hz. The camera was connected to a personal computer via USB3.0 interface and recorded using Flycapture 2 acquisition software (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR) with Motion JPEG codec. For optogenetic activation experiments, longpass filter (LP780 IR Longpass Filter, LP780-25.5, Midwest Optical Systems, Palatine, IL) was used to remove the light from LEDs. Analysis of lunging and unilateral wing extension was performed as described in Hoopfer et al. (2015). Briefly, fly tracking data were obtained using Caltech fly tracking software (FlyTracker) and the behavior classifiers, developed using JAABA were used to analyze lunging and unilateral wing extension behaviors. For experiments where a small difference between experimental and control genotypes was observed, the scores for lunging and unilateral wing extension were manually validated to eliminate false positives. The SBPI (social behavior proportion index) was calculated as follows. The SBPI = (number of lunges – number of unilateral wing extensions)/(number of lunges + number of unilateral wing extensions). In the case where both the number of lunges and of unilateral wing extensions was zero, we defined the SBPI as zero.

Statistical Analysis

Boxplots indicated the median flanked by the 25th and 75th percentiles (box) and whiskers showing 5th and 95th percentiles.

Statistical analyses were performed using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and Prism5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Outliers were defined as data points above the 95th percentile or below the 5th percentile of the data, and included in statistical analyses. For comparisons of more than three groups, we used the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. In the case of rejecting the null hypothesis that medians of all experimental groups were the same, we performed post-hoc pairwise Mann-Whitney U-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Custom software tools used for this study include FlyTracker software (Eyrún Eyjólfsdóttir and Pietro Perona, Caltech), which is available for download at http://www.vision.caltech.edu/Tools/FlyTracker/. The lunging and unilateral wing extension classifiers for JAABA software (Kabra et al., 2013) were developed in the Anderson lab (Hoopfer et al., 2015) and available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Full genotypes of flies in each experiment, Related to the STAR Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Melkonian and J. Choi for fly stock maintenance, Y. Aso and H. Tanimoto for sharing fly lines, M. Gallio and Y. Chen for advice on GRASP experiments; members of the Anderson Lab fly group for advice, C. Chiu for lab management, G. Mancuso for administrative assistance, and P. Sternberg and B. Weissbourd for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIDA Grant 2R01-DA031389, and a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship to K.W. D.J.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. K.W. dedicates this paper to the memory of his PhD advisor, the late Dr. Yoshiki Sasai.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and one table.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KW conducted most of the experiments, created FLP ON/OFF Kir2.1, ey-nls::FLPo and UAS-Oamb transgenic flies, participated in experimental conception and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and co-wrote the manuscript. HC conducted the functional imaging experiments for Figure 5; BDP created OAR CRM-GAL4 transgenic flies, and FLP-ON effectors for Figure S5; AW established functional imaging setup for Figure 4; EDH conducted behavioral experiments and analysis of data for Figure S5E–I; GMR contributed unpublished reagents. DJA conceived the project, participated in experimental design and interpretation of data, co-wrote the manuscript, and provided overall supervision for the project.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adamo SA, Linn CE, Hoy RR. The role of neurohormonal octopamine during “fight or flight” behaviour in the field cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. The Journal of experimental biology. 1995;198:1691–1700. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.8.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ. Circuit modules linking internal states and social behaviour in flies and mice. Nature reviews. 2016;17:692–704. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JC, Fernández MP, Yu Q, Leary GP, Leung AKW, Kavanaugh MP, Kravitz EA, Certel SJ. Octopamine Neuromodulation Regulates Gr32a-Linked Aggression and Courtship Pathways in Drosophila Males. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina K, Watanabe K, Duistermars BJ, Hoopfer E, González CR, Eyjólfsdóttir EA, Perona P, Anderson DJ. Tachykinin-Expressing Neurons Control Male-Specific Aggressive Arousal in Drosophila. Cell. 2014;156:221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer TO, Benton R. Sexual circuitry in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;38:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon JP, Thompson KS, Stern M. Identified octopaminergic neurons provide an arousal mechanism in the locust brain. Journal of neurophysiology. 1995;74:2739–2743. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier A, Wittek B, Brembs B. Drosophila as a new model organism for the neurobiology of aggression? Journal of Experimental Biology. 2002;205:1233–1240. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.9.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines RA, Uhler JP, Thompson A, Sweeney ST, Bate M. Altered electrical properties in Drosophila neurons developing without synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfanz S, Strunker T, Frings S, Baumann A. A family of octopamine [corrected] receptors that specifically induce cyclic AMP production or Ca2+ release in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;93:440–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI. Beyond the connectome: How neuromodulators shape neural circuits. Bioessays. 2012;34:458–465. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Marder E. From the connectome to brain function. Nature methods. 2013;10:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JA, Edinger H, Siegel A. Intrahypothalamic injections of norepinephrine facilitate feline affective aggression via alpha 2-adrenoceptors. Brain research. 1990;525:285–293. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90876-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D, Konishi M. Neural control of behavior. Annual review of neuroscience. 1978;1:35–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.01.030178.000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschek CB, Apiyo DO, Soares TA, Engelmann HE, Pefaur NB, Straatsma TP, Baird CL. Engineering an ultra-stable affinity reagent based on Top7. Protein engineering, design & selection: PEDS. 2009;22:325–332. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggman KL, Kristan WB. Multifunctional pattern-generating circuits. Annual review of neuroscience. 2008;31:271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CJ, Huetteroth W, Owald D, Perisse E, Krashes MJ, Das G, Gohl D, Silies M, Certel S, Waddell S. Layered reward signalling through octopamine and dopamine in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;492:433. doi: 10.1038/nature11614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch S, Selcho M, Ito K, Tanimoto H. A map of octopaminergic neurons in the Drosophila brain. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2009;513:643–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachero S, Ostrovsky AD, Yu JY, Dickson BJ, Jefferis GSXE. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Current biology: CB. 2010;20:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]