Abstract

Objective

Since 2008, the Oxford Diagnostic Horizon Scan Programme has been identifying and summarising evidence on new and emerging diagnostic technologies relevant to primary care. We used these reports to determine the sequence and timing of evidence for new point-of-care diagnostic tests and to identify common evidence gaps in this process.

Design

Systematic overview of diagnostic horizon scan reports.

Primary outcome measures

We obtained the primary studies referenced in each horizon scan report (n=40) and extracted details of the study size, clinical setting and design characteristics. In particular, we assessed whether each study evaluated test accuracy, test impact or cost-effectiveness. The evidence for each point-of-care test was mapped against the Horvath framework for diagnostic test evaluation.

Results

We extracted data from 500 primary studies. Most diagnostic technologies underwent clinical performance (ie, ability to detect a clinical condition) assessment (71.2%), with very few progressing to comparative clinical effectiveness (10.0%) and a cost-effectiveness evaluation (8.6%), even in the more established and frequently reported clinical domains, such as cardiovascular disease. The median time to complete an evaluation cycle was 9 years (IQR 5.5–12.5 years). The sequence of evidence generation was typically haphazard and some diagnostic tests appear to be implemented in routine care without completing essential evaluation stages such as clinical effectiveness.

Conclusions

Evidence generation for new point-of-care diagnostic tests is slow and tends to focus on accuracy, and overlooks other test attributes such as impact, implementation and cost-effectiveness. Evaluation of this dynamic cycle and feeding back data from clinical effectiveness to refine analytical and clinical performance are key to improve the efficiency of point-of-care diagnostic test development and impact on clinically relevant outcomes. While the ‘road map’ for the steps needed to generate evidence are reasonably well delineated, we provide evidence on the complexity, length and variability of the actual process that many diagnostic technologies undergo.

Keywords: Point-of-care Systems, Diagnosis, PRIMARY CARE, framework, evidence based medicine, horizon scanning reports

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first data on evidence gaps in point-of-care diagnostic test evaluation in primary care, answering an important clinical need.

We extracted data from multiple consistently conducted horizon scan reports.

Our approach might ignore relevant research, but systematic evidence gaps identified suggest findings to be robust.

Our analyses are limited by the horizon scan report publication date.

Introduction

Primary care is becoming increasingly complex due to a rise in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, the pressure of short consultation times and the fragmented nature of primary and secondary care. Delayed or missed diagnoses are the most common reason for malpractice claims.1 Therefore, there is a huge demand for innovations that enable efficient and accurate diagnostic assessment within a general practitioner (GP)’s consultation. Consequently, the development of point-of-care diagnostic tests is currently a hotbed of activity.2 These tests have the potential to significantly improve the efficiency of diagnostic pathways, providing test results within the time frame of a single consultation, enabling them to influence immediate patient management decisions.

A potential barrier to this innovative activity however is the slow and haphazard nature of the current pathway to adoption for new healthcare technologies.3 This is particularly the case for diagnostic tests, where uptake is highly variable between settings and notable inconsistencies lie in the speed at which they are adopted.4 One possible cause of this inefficiency is the slow generation of evidence of efficacy relevant to the target clinical settings.

To provide an efficient means of identifying, summarising and disseminating the evidence for emerging diagnostic technologies relevant to primary care settings, the Oxford Diagnostic Horizon Scanning Programme was established in 2008 (currently funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative).5 New technologies are identified through systematic literature searches and interactions with clinicians and the diagnostics industry. These are then prioritised using a defined list of criteria.6 Evidence is gathered using systematic searches of the published literature and supplementary information obtained from manufacturer or trade websites and through web search engines, which are then used to summarise the analytical and diagnostic accuracy of the point-of-care test,7 impact of the test on patient outcomes and health processes, cost-effectiveness of the test and current guidelines for use within routine care in the UK. The reports, indexed in the TRIP database8 and freely available from the Horizon Scan Programme’s website (www.oxford.dec.nihr.ac.uk), are actively disseminated to the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, clinical researchers and commissioners of healthcare services and highlight any further research requirements to facilitate evidence-based adoption decisions.

To date, 40 horizon scan reports have been completed, all following an identical protocol.

These horizon scan reports provide a unique opportunity to describe the evidence trajectory of new point-of-care diagnostic tests relevant to primary care settings and identify common evidence gaps.

Methods

This is a descriptive study of all 40 horizon scan reports published to date by the Oxford Horizon Scan programme. For each horizon scan report, we extracted the year of publication and the disease area (classified per clinical domain of the International Classification of Primary Care—Revised Second Edition (ICPC2-R) 17) (see online supplementary file 1). We subsequently reviewed all studies that were included in the horizon scan reports (including systematic reviews) and extracted data on year of publication, size of the study, point-of-care test device(s) and its intended role. The intended roles were defined as ‘triage’, in which the new test is used at the start of the clinical pathway, ‘replacement’, in which the new test replaces an existing test, either as a faster equivalent test or to replace a non-point-of-care laboratory test, or ‘add-on’ in which the new test is performed at the end of a clinical pathway.9 Depending on the role, different types of evidence are required before a new point-of-care test can be adopted in routine care.10

bmjopen-2016-015760supp001.pdf (57.2KB, pdf)

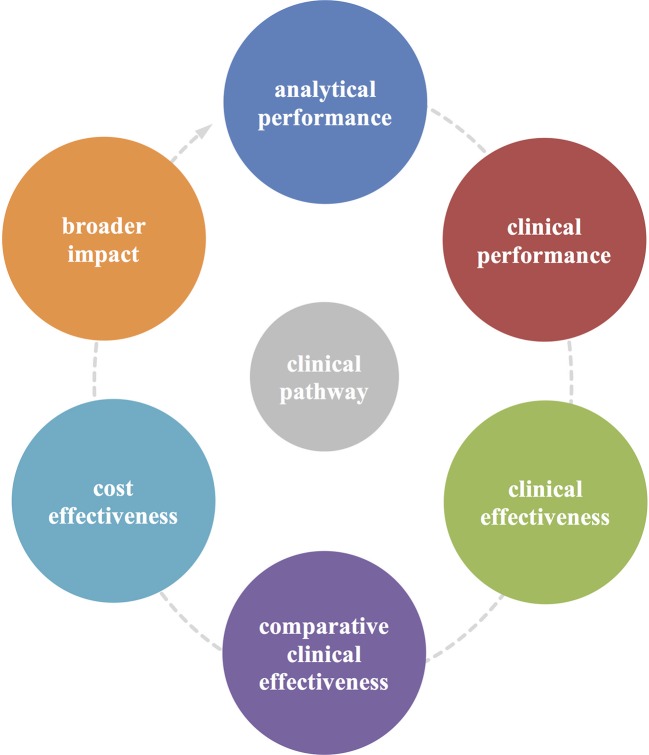

We extracted data on study design and primary outcomes and used the dynamic evidence framework developed by Horvath et al,11 as shown in figure 1, to classify the type of evidence, defined as (1) analytical performance, (2) clinical performance, (3) clinical effectiveness, (4) comparative clinical effectiveness, (5) cost-effectiveness and (6) broader impact.

Figure 1.

Horvath et al 11’s cyclical framework for the evaluation of diagnostic tests. This framework illustrates the key components of the test evaluation process. (1) Analytical performance is the aptitude of a diagnostic test to conform to predefined quality specifications. (2) Clinical performance examines the ability of the biomarker to conform to predefined clinical specifications in detecting patients with a certain clinical condition or in a physiological state. (3) Clinical effectiveness focuses on the test’s ability to improve health outcomes that are relevant to an individual patient, also allowing comparison (4) of effectiveness between tests. (5) A cost-effectiveness analysis compares the changes in costs and health effects of introducing a test to assess the extent to which the test can be regarded as providing value for money. (6) Broader impact encompasses the consequences (eg, acceptability, social, psychological, legal, ethical, societal and organisational consequences) of testing beyond the above-mentioned components.

Analytical performance is the aptitude of a diagnostic test to conform to predefined quality specifications.12 13 Clinical performance examines the ability of the biomarker to conform to predefined clinical specifications in detecting patients with a particular clinical condition or in a physiological state.14 Clinical effectiveness focuses on the test’s ability to improve health outcomes that are relevant to the individual patient.14 A cost-effectiveness analysis compares the changes in costs and in health effects of introducing a test to assess the extent to which the test can be regarded as providing value for money. Broader impact encompasses the consequences (eg, acceptability, social, psychological, legal, ethical, societal and organisational consequences) of testing beyond the above-mentioned components.

For point-of-care tests that had evidence on each of these components, we calculated the median time (in years) for a technology to complete the evaluation cycle.

We assessed whether the study was conducted in a setting that was relevant for primary care, which was defined as GP surgeries (clinics), outpatient clinics, walk-in (or urgent care) centres and emergency departments. Data extraction was piloted on 20 reports by BS and checked by JV and PT after which improvements were made to the final data extraction sheet. Three authors (JYV, BS and PJT) independently single-extracted data of the included studies.

Results

We screened 40 horizon scan reports and extracted data from the 500 papers (including 41 systematic reviews) referenced by these reports (table 1). Ten horizon scan reports examined a point-of-care test relevant to cardiovascular disease, six to respiratory diseases and five to each of endocrine/metabolic diseases, digestive diseases and general/unspecified diseases. A further nine horizon scan reports examined a health problem relevant to a range of other disease areas. The intended role of the test was triage in 14 (35%), replacement in 20 (50%) and add-on in 6 (15%) of the 40 horizon scan reports.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of horizon scan reports by clinical domain

| Diagnostic tests by clinical domain | Date report published |

Studies in primary care (n)/all studies (N) | Sample sizes of primary studies (range) | Publication dates primary studies (range) | Intended role of the test | Components missing |

| Cardiovascular | 21/158 | |||||

| The D-dimer test for ruling out DVT in primary care | 2009 | 2/9 | 1028–1295 | 1997–2009 | T | I/IV/VI |

| Point-of-care test for INR coagulometers | 2010 | 16/32 | 18–892 | 2000–2010 | R | – |

| Point-of-care test for cardiac troponin | 2011 | 0/18 | 20–2263 | 2001–2011 | R | – |

| Point-of-care pulse wave analysis | 2011 | 0/7 | 22–749 | 2008–2011 | R | III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care test for BNP | 2011 | 1/15 | 150–606 | 2001–2011 | T | IV |

| Handheld ECG monitors for the detection of atrial fibrillation in primary care | 2013 | 0/9 | 18–505 | 1990–2012 | R | I/IV/V |

| Genotyping polymorphisms of warfarin metabolism | 2013 | 0/2 | 20–112 | 2009–2010 | T | III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care test for hFABP | 2014 | 1/21 | 52–1074 | 2003–2013 | A | I/VI |

| Portable ultrasound devices | 2014 | 1/24 | 3–943 | 1993–2013 | T | VI |

| Point-of-care test for a panel of cardiac markers | 2014 | 0/21 | 33–5201 | 1999–2012 | T | I/III/V/VI |

| Digestive | 12/81 | |||||

| Point-of-care test for hepatitis C virus | 2011 | 0/6 | 100–2206 | 1999–2011 | R | IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care test for coeliac disease | 2012 | 1/9 | 87–2690 | 2004–2009 | T | I/III/IV/V |

| Transcutaneous bilirubin measurement | 2013 | 0/28 | 31–849 | 1996–2011 | T | I/III/IV |

| Point-of-care calprotectin tests | 2014 | 1/8 | 14–140 | 2008–2012 | T | I/III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care faecal occult blood testing | 2014 | 10/30 | 100–85149 | 1990–2013 | T | – |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 28/76 | |||||

| Point-of-care blood test for ketones in diabetes | 2009 | 6/9 | 33–529 | 2000–2006 | T | – |

| Point-of-care test for the analysis of lipid panels | 2010 | 9/13 | 34–4968 | 1995–2010 | R | – |

| Point-of-care test for HbA1c | 2010 | 6/7 | 23–7893 | 2003–2010 | R | IV* |

| Point-of-care test for thyroid-stimulating hormone | 2013 | 0/1 | 64–64 | 1999–1999 | R | I/III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care HbA1c tests: diagnosis of diabetes | 2016 | 7/46 | 23–6226 | 1996–2015 | R | III/IV* |

| Female genital | 2/8 | |||||

| Chlamydia trachomatis testing | 2009 | 2/8 | 162–2517 | 1998–2009 | R | II/V/VI |

| General and unspecified | 7/34 | |||||

| Point-of-care test for total white cell count | 2010 | 1/6 | 120–500 | 2000–2009 | R | III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care test for CRP | 2011 | 6/8 | 20–898 | 1997–2011 | R | – |

| Point-of-care test for procalcitonin | 2012 | 0/8 | 54–384 | 2001–2010 | A | IV |

| Non-contact infrared thermometers | 2013 | 0/6 | 90–855 | 2005–2013 | A | III/V/VI |

| Point-of-care test for malaria | 2015 | 0/6 | 98–98 | 1999–2014 | R | I/V |

| Musculoskeletal | 0/1 | |||||

| Autoimmune markers for rheumatoid arthritis | 2012 | 0/1 | 880–880 | 2008–2008 | R | I/III/IV/V/VI |

| Neurological | 1/9 | |||||

| Point-of-care test for handheld nerve conduction measurement devices for carpal tunnel syndrome | 2012 | 1/9 | 33–1190 | 2000–2011 | R | IV/V |

| Pregnancy | 2/11 | |||||

| Urinalysis self-testing in pregnancy | 2014 | 2/9 | 49–4 44 220 | 1991–2012 | A | IV |

| Point-of-care test for quantitative blood hCG | 2015 | 0/2 | 40–40 | 2014–2015 | T | III/IV/V/VI |

| Respiratory | 25/84 | |||||

| Pulse oximetry in primary care | 2009 | 1/4 | 114–2127 | 1997–2004 | T | I/III/IV/V |

| A portable handheld electronic nose in the diagnosis of cancer, asthma and infection | 2009 | 5/8 | 30–665 | 1999–2009 | T | III/IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care spirometry | 2011 | 4/11 | 13–1041 | 1996–2009 | R | V |

| Point-of-care automated lung sound analysis | 2011 | 3/22 | 1–100 | 1996–2010 | A | IV/V |

| Point-of-care tests for influenza in children | 2012 | 8/29 | 73–9186 | 2002–2011 | R | I/IV |

| Point-of-care tests for group A streptococcus | 2015 | 4/10 | 121–892 | 2002–2015 | R | I |

| Skin | 1/7 | |||||

| Dermoscopy for the diagnosis of melanoma in primary care | 2009 | 1/7 | 96–3053 | 2001–2008 | T | I/IV/V |

| Urological | 7/31 | |||||

| Point-of-care urine albumin–creatinine ratio test | 2010 | 6/11 | 83–4968 | 1999–2010 | R | – |

| Point-of-care test for creatinine | 2014 | 1/10 | 20–401 | 2007–2013 | R | IV/V/VI |

| Point-of-care NGAL tests | 2015 | 0/10 | 100–1219 | 2007–2013 | A | III/IV/V |

| Grand total | 106/500 |

Evaluation components: I, analytical performance; II, clinical performance; III, clinical effectiveness; IV, comparative clinical effectiveness; V, cost-effectiveness; VI, broader impact.

*Same diagnostic technology.

A, add-on; BNP, B-natriuretic peptide; CRP, C reactive protein; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; hFABP, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein; INR, international normalised ratio; n, number; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; R, replacement; T, triage

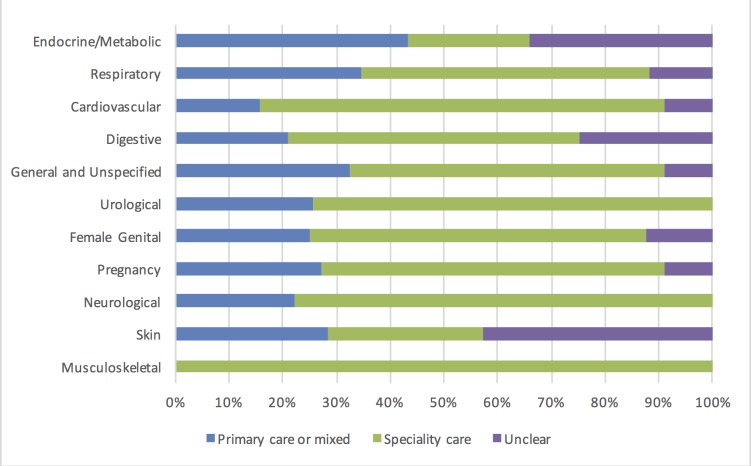

We found a median of nine primary studies (IQR 7–15.8) per horizon scan report with a median time between first and last publication of 10 years (IQR 6.8–13.3). Across all horizon scan reports, on average, only 19% (95% CI 11.4% to 20.7%) of studies were performed in primary care (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Setting (%) of the studies by disease area (according to the International Classification of Primary Care-Second edition coding).

Of all studies, 30.4% (n=152) assessed analytical performance of the diagnostic technology, providing evidence for this component in 25 (62.5%) of the 40 horizon scan reports.

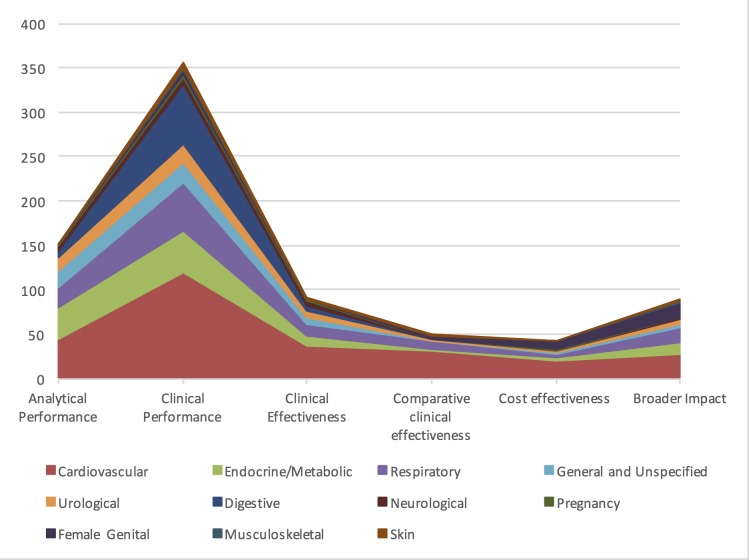

Clinical performance was evaluated in 71.2% (n=356) of all studies, while only 18.2% (n=91) of studies evaluated clinical effectiveness of the diagnostic technology. A further 10.0% (n=50) compared clinical effectiveness of two or more point-of-care tests, and only 8.6% (n=43) of the 500 papers evaluated cost-effectiveness (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Test evaluation component by disease area in absolute number (n) of studies.

Clinical performance was often assessed earlier (in 16 tests) or together (in 12) with analytical performance and not assessed at all for 6 tests. Broader impact such as acceptability was tested before evidence on clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness was available in 11 horizon scan reports.

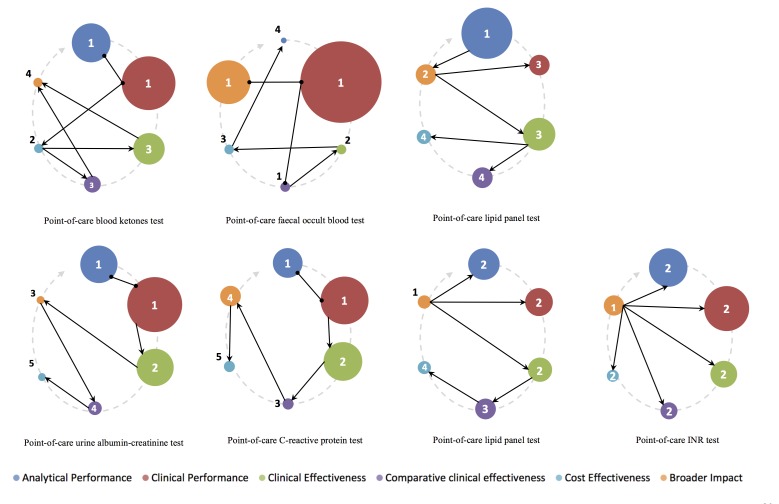

Figure 4 shows the number of years between the horizon scan report and original paper publication date for each evaluation component, split by intended role of the point-of-care test. The size of the bubbles represents the number of studies proportionate to all studies for the intended role, clearly depicting the emphasis on clinical performance and paucity of clinical effectiveness studies. Furthermore, tests acting as a triage instrument tend to spend more time on evidence generation than tests replacing an existing one or add-on tests performed at the end of the clinical pathway.

Figure 4.

Number of years between horizon scan report and original paper publication date by the intended role for each evaluation component. Size of bubbles represents number of studies proportionate to all studies for the intended role. BNP, B-natriuretic peptide; CRP, C reactive protein; FOBT, faecal occult blood test; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; hFABP, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein; INR, international normalised ratio; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; WBC, white cell count.

Only seven (17.5% (95% CI 7.3% to 32.8%)) horizon scan reports included evidence for all evaluation components with a median time to complete the evaluation cycle of 9 years (IQR 6–13 years). Of these, tests acting as a triage instrument (in three reports) had a median of 15 years (IQR 10–19) while tests replacing an existing one (in four reports) had 9 years (IQR 5–11) (figure 4).

Even in the latter category of diagnostic technology replacing existing tests, where nearly half of studies (49.4%; n=247) have been performed, there was a clear imbalance between studies merely focusing on analytical or clinical performance (87.4%) and the few studies advancing to clinical effectiveness (21.1%).

The sequence of evidence generation over time for the seven horizon scan reports which had completed the evaluation cycle varied widely, as shown in figure 5. The size of the bubbles represents the proportion of studies for each evaluation component. The grey arrow shows the sequence we would expect, starting at analytical performance (at 12 o’clock) and completing at broader impact analysis (at 10 o’clock). The arrows and numbered bubbles represent the actual time sequence of evidence generation.

Figure 5.

Sequence of evidence generation for all seven horizon scan reports completing the full evaluation cycle. INR, international normalised ratio.

Very few point-of-care test evaluations seem to follow the expected sequence. In fact, only the report on point-of-care C reactive protein testing seemed to generally follow a linear temporal sequence from analytical performance towards broader impact. Some diagnostic technology, such as point-of-care international normalised ratio (INR) testing, had evidence generated for the broader impact component before any other component, suggesting that some diagnostic technologies are adopted in routine clinical care prior to any published evidence on clinical performance or effectiveness.

Discussion

Main findings

Our findings suggest that most point-of-care diagnostic tests undergo clinical performance assessment, but very few progress to evaluation of their broader impact or cost-effectiveness, even in the more established and frequently reported clinical domains, such as cardiovascular disease. Some point-of-care tests even skip essential stages such as clinical effectiveness, yet are still implemented in routine care. We present a novel way to visualise the gaps in the evidence generation through bubble plots and dynamic cycle illustration.

Strengths and limitations

Our study provides novel data on common evidence gaps in the evaluation of novel point-of-care tests for a wide range of clinical conditions. The extensive library of existing horizon scan reports and the methodological rigour in which they are produced provided an ideal opportunity to review the pathway of evidence for novel point-of-care diagnostic technologies relevant to the primary care settings. The chosen topics of the reports result from a comprehensive approach to identify new or emerging diagnostic tests, including literature searches and interaction with the diagnostics industry and clinicians, prioritising technologies relevant to primary care. We have, however, no measure of how reproducible this prioritisation process is, and potentially risks greater or lesser inclusion of various disease areas. Evidence from reports on other clinical topics might provide different findings. Further to this, our review is limited to publication date of each report, thus potentially overlooking evidence generated following publication. Our approach might arguably ignore relevant (unpublished) research carried out (eg, studies performed during test development by industry), but the commonalities in the evidence gaps across the reports suggest that our findings are robust.

Three authors (JYV, BS and PJT) independently single-extracted data of the 500 included studies, making it impossible to test for inter-rater agreement.

Comparison with the existing literature

Previous evidence has shown that the adoption of a diagnostic technology is often insufficient to achieve a benefit, and in most cases, a change of care process is essential.15 The market for point-of-care tests is growing rapidly,16 and there is a clear demand from primary care clinicians for these tests to help them diagnose a range of conditions.17 18 Critical appraisal of new diagnostic technologies is considered essential to facilitate implementation.11 Several evaluation frameworks have been identified,19 most of which describe the evaluation process as a linear process, similar to the staged evaluation of drugs.

Considering the interactions between different evaluation components and the need for certain tests to re-enter the evaluation process after updates to the underlying technology,20 it may be more realistic to assess these components in a cyclic and repetitive process.11

Implications

The slow adoption of novel point-of-care tests may result from the paucity of technologies following the expected sequence of evidence generation. Specifically, there is a need to shift emphasis from examining clinical performance of point-of-care tests to comparative clinical effectiveness and broader impact assessment. We recommend using a structured dynamic approach, presenting the results in a visually appealing manner for both industry (during development and pursuit for regulatory approval) and research purposes. Policy-makers and guideline developers should be aware of this cyclical nature; assuming test evaluation is a linear process results in a less efficient evidence generation pathway. For example, assessing the cost-effectiveness early on in the development phase of novel point-of-care test can help determine where exactly it fits in the clinical pathway and thus ensure that the evidence subsequently generated is relevant to that population and setting.

Conclusions

Considering that evidence generation for new tests takes on an average 9 years, test developers need to be aware of the time and investment required. While the ‘road map’ for the steps needed to generate evidence are reasonably well delineated, we provide evidence on the complexity, length and variability of the actual process that many diagnostic technologies undergo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article presents independent research part funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors would like to thank all original horizon scan report authors.

Footnotes

Contributors: BS, MJT and AVdB conceived the study. JYV, PJT and BS did data extraction. JYV designed and performed the analyses, which were discussed with PJT, MJT, AP, CPP, BS and AVdB. JYV drafted this report and JYV, PJT, MJT, AP, CPP, BS and AVdB codrafted and commented on the final version. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JYV affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: JYV, PJT, MJT, AP, CPP, BS and AVdB are supported through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative Oxford at Oxford Health Foundation Trust (award number IS_DEC_0812_100).

Competing interests: MJT has received funding from Alere to conduct research and has provided consultancy to Roche Molecular Diagnostics. He is also a co-founder of Phoresia which is developing point-of-care tests. All the other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data for these analyses are included in the manuscript or online appendices. No additional data available.

References

- 1. Wallace E, Lowry J, Smith SM, et al. The epidemiology of malpractice claims in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002929. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GV Research IVD. Market Analysis By Product (Tissue Diagnostics, Molecular Diagnostics, Professional Diagnostics, Diabetes Monitoring) And Segment Forecasts To 2020. 100 Pune, India: Grand View Research, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, et al. How to spread good ideas: a systematic review of the literature on diffusion, dissemination and sustainability of innovations in health service delivery and organisation. London: NCCSDO, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Britain G, National Health S. The NHS atlas of variation in diagnostic services: reducing unwarranted variation to increase value and improve quality. Great Britain: Right Care, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oxford DEC. NIHR Diagnostic evidence Cooperative Oxford. 2016. https://www.oxford.dec.nihr.ac.uk/

- 6. Plüddemann A, Heneghan C, Thompson M, et al. Prioritisation criteria for the selection of new diagnostic technologies for evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:109. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mallett S, Halligan S, Thompson M, et al. Interpreting diagnostic accuracy studies for patient care. BMJ 2012;345:e3999. 10.1136/bmj.e3999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brassey J. University of Wales CoMCfRS. TRIP database. Cardiff: University of Wales, College of Medicine, Centre for Research Support, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bossuyt PM, Irwig L, Craig J, et al. Comparative accuracy: assessing new tests against existing diagnostic pathways. BMJ 2006;332:1089–92. 10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van den Bruel A, Cleemput I, Aertgeerts B, et al. The evaluation of diagnostic tests: evidence on technical and diagnostic accuracy, impact on patient outcome and cost-effectiveness is needed. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:1116–22. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horvath AR, Lord SJ, StJohn A, et al. From biomarkers to medical tests: the changing landscape of test evaluation. Clin Chim Acta 2014;427:49–57. 10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fraser CG, Kallner A, Kenny D, et al. Introduction: strategies to set global quality specifications in laboratory medicine. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:477–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh S, Chang SM, Matchar DB, et al. Chapter 7: grading a body of evidence on diagnostic tests. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(Suppl 1):47–55. 10.1007/s11606-012-2021-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Global Harmonization Task Force. Clinical Evidence for IVD medical devices – Key Definitions and Concepts: Global Harmonization Task Force, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. St John A. The Evidence to Support Point-of-Care Testing. Clin Biochem Rev 2010;31:111–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stone Hearth News. Point of care test (POCT) market will see faster revenue growth in 2013 than tests sent to central labs for processsing. 2012. http://www.stonehearthnewsletters.com/point-of-care-test-poct-market-will-see-faster-revenue-growth-in-2013-than-tests-sent-to-central-labs-for-processing/health-care/

- 17. Howick J, Cals JW, Jones C, et al. Current and future use of point-of-care tests in primary care: an international survey in Australia, Belgium, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005611 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turner PJ, Van den Bruel A, Jones CH, et al. Point-of-care testing in UK primary care: a survey to establish clinical needs. Fam Pract 2016;33:388–94. 10.1093/fampra/cmw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lijmer JG, Leeflang M, Bossuyt PM. Proposals for a phased evaluation of medical tests. Med Decis Making 2009;29:E13–E21. 10.1177/0272989X09336144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thompson M, Weigl B, Fitzpatrick A, et al. More Than Just Accuracy: A Novel Method to Incorporate Multiple Test Attributes in Evaluating Diagnostic Tests Including Point of Care Tests. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med 2016;4:2800208:1–8. 10.1109/JTEHM.2016.2570222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015760supp001.pdf (57.2KB, pdf)