Abstract

Introduction

Physical activity, healthy eating and maintaining a healthy weight are associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer and with improved mental health. Despite these benefits, many men do not meet recommended physical activity guidelines and have poor eating behaviours. Many health promotion programmes hold little appeal to men and consequently fail to influence men’s health practices. HAT TRICK was designed as a 12-week face-to-face, gender-sensitised intervention for overweight and inactive men focusing on physical activity, healthy eating and social connectedness and was delivered in collaboration with a major junior Canadian ice hockey team (age range 16–20 years). The programme was implemented and evaluated to assess its feasibility. This article describes the intervention design and study protocol of HAT TRICK.

Methods and analysis

HAT TRICK participants (n=60) were men age 35 years, residing in the Okanagan Region of British Columbia, who accumulate 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity a week, with a body mass index of >25 kg/m2 and a pant waist size of >38’. Each 90 min weekly session included targeted health education and theory-guided behavioural change techniques, as well as a progressive (ie, an increase in duration and intensity) group physical activity component. Outcome measures were collected at baseline, 12 weeks and 9 months and included the following: objectively measured anthropometrics, blood pressure, heart rate, physical activity and sedentary behaviour, as well as self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour, diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep habits, risk of depression, health-related quality of life and social connectedness. Programme feasibility data (eg, recruitment, satisfaction, adherence, content delivery) were assessed at 12 weeks via interviews and self-report.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Okanagan Behavioural Research Ethics Board (reference no H1600736). Study findings will be disseminated through academic meetings, peer-reviewed publication, web-based podcasts, social media, plain language summaries and co-delivered community presentations.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN43361357,Pre results

Keywords: men’s health, masculinity, physical activity, dietary behaviors, overweight/obese, social connectedness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

HAT TRICK is a gender-sensitised programme designed to engage ‘hard-to-reach’ men with their health by resonating with and appealing to masculine ideals.

The HAT TRICK programme has the potential to be transferred across a number of male populations and settings, thus further increasing its reach to a large proportion of men.

This study has a robust evaluation plan, using objective and subjective measures of physical activity, and a variety of measures to assess programme feasibility.

Given the exploratory nature of this feasibility study, it is limited in examining causal effect in terms of behavioural change.

Introduction

Engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviours including physical activity (PA) and healthy eating to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight can reduce the risk for developing chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, depression and premature mortality.1–4 Despite the benefits associated with these lifestyle behaviours, up to 83% of men are not meeting the recommended PA guidelines3 5 6 (ie, at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous intensity PA per week) and have poor eating behaviours.7 8 Accordingly, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among men is on the rise and continues to grow at a disproportionate rate to their female counterparts.9 Complicating matters is the fact that many men have proved reluctant and/or ‘hard to reach’ in healthy lifestyle and weight management programmes, making disease and illness prevention initiatives difficult.10–13

Traditionally, a central challenge associated with engaging men in taking more active care in their health was a perception that attention to one’s health ran counter to masculine ideals of strength, self-reliance and independence.14–17 Men often associate health promoting practices as feminine, or a sign of weakness, and consequently threatening to their status in masculine hierarchies.15 18 Thus, many men refrain from engaging in health promotion behaviours, including attending PA, healthy eating and weight management programmes.19 20 However, Pringle et al 21 suggested that men’s apparent detachment from healthy behaviours is an indication that typical approaches to health are unappealing and/or irrelevant to their masculine values and virtues. Previous men-centred PA and healthy eating related research22–24 has revealed that careful consideration of ‘place’ (ie, physical setting), along with a tailored approach that aligns with men’s values and interests, can indeed support increases in health promoting behaviours.25–27 This work supports the notion that there is value in providing men with health promotion opportunities in venues where they participate in and/or watch sport and recreational activities.21 27 28

Recent research has highlighted the potential for professional sports teams/clubs to attract and engage men in healthy lifestyle behaviours.29–31 Such settings have proved a powerful draw for men due to familiar, comfortable and/or appealing environments which they offer and the sociocultural connections men often make with particular teams and fellow supporters in terms of loyalty, identity and belonging.27 29 32 33 Furthermore, professional/elite sport clubs and settings offer a unique opportunity to support men’s health because they provide health promoters with a potentially large captive audience of men in an environment that plays to masculine values and virtues.21 22 29 33 For example, the Football Fans in Training (FFIT) intervention targeted overweight Scottish men and reported a significant reduction in weight at 12 months postintervention (mean weight loss of 4.95 kg),27 as well as significant positive changes in blood pressure, diet, self-reported PA and physical quality of life. This programme has since been expanded to include professional soccer clubs across Europe34 and has been adapted to addition sports (ie, Rugby).35

Within this context, the gender-sensitised HAT TRICK programme was designed to engage men with their health by resonating with and appealing to masculine ideals. Its delivery model is founded on the strong collaboration with the Kelowna Rockets Hockey Team, a major junior ice hockey team within the Canadian Hockey League.36 Garnering the social and cultural connections that men often cultivate with particular sports teams can be a ‘lynchpin’ to engaging men in healthful behaviours in that this approach recognises the interests and preferences of men, while fostering an environment that promotes a sense of identity, camaraderie and healthy living. This paper describes the intervention design and methodological protocols of HAT TRICK.

Methods and analysis

Objectives

The specific objectives of the HAT TRICK study were to:

Determine feasibility and acceptability of HAT TRICK, a health promotion programme focused on PA, healthy eating and connectedness for inactive, overweight men.

Estimate effectiveness in terms of changes over time in PA, sedentary behaviour, dietary behaviours, weight, smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep habits, risk for depression, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and social connectedness.

Use findings to refine the programme and inform the development of a future large-scale randomised control trial (RCT).

Study design

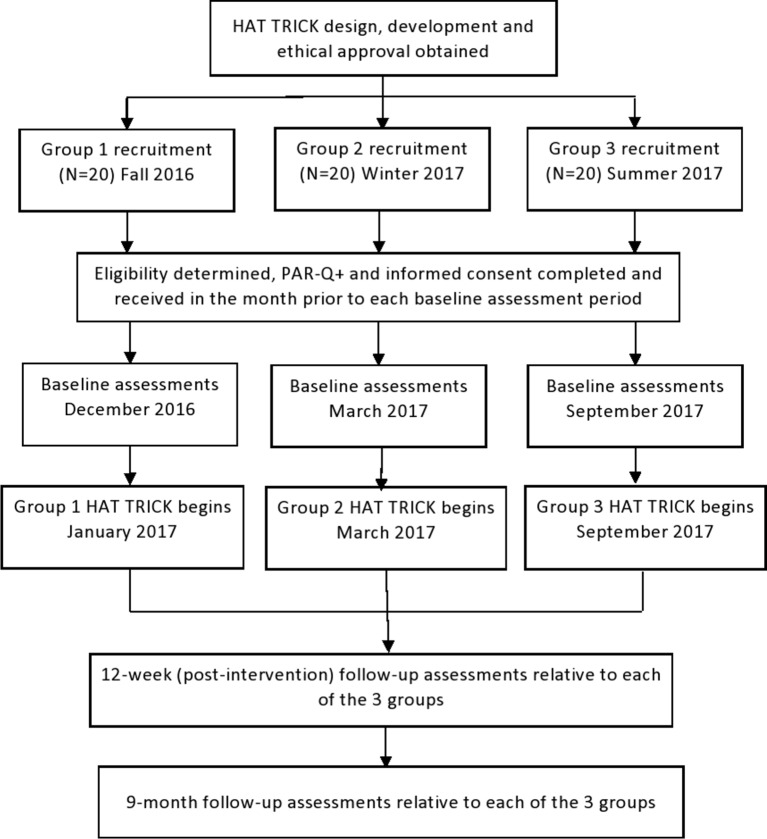

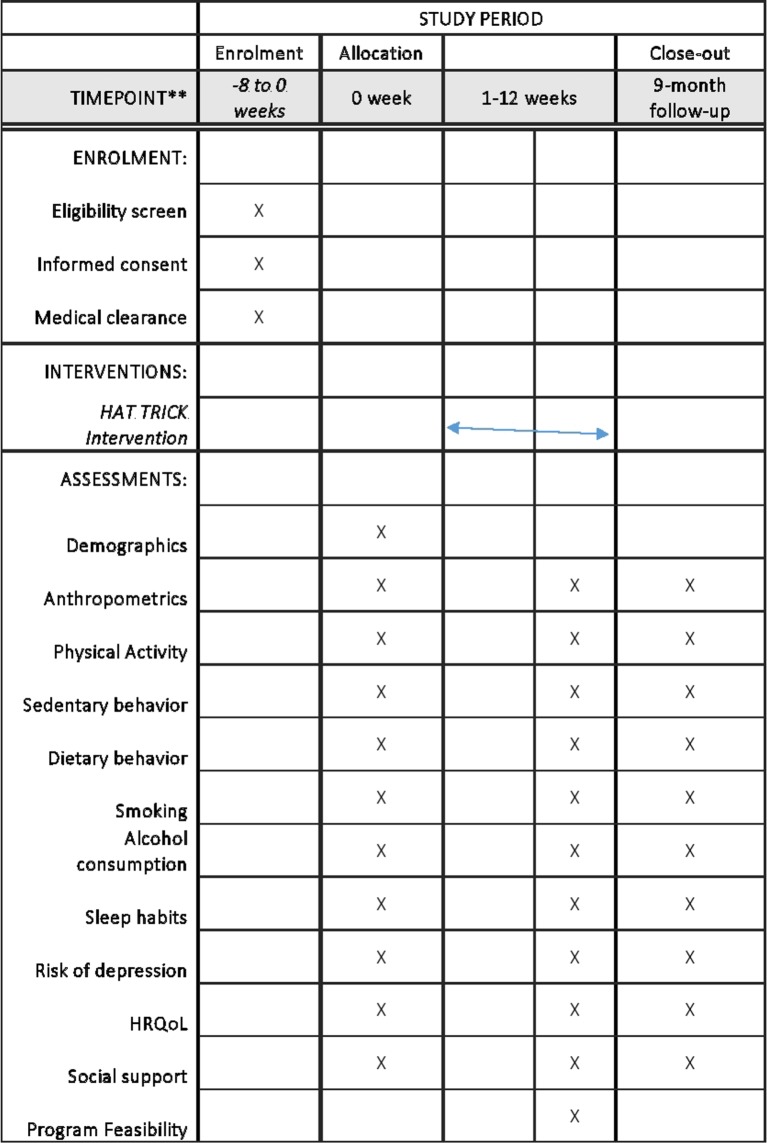

This study protocol was prepared according to Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).37 This study used a quasi-experimental, pretest–post-test design to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a men’s health promotion programme focused on PA, healthy eating and social connectedness. Data collection occurred at baseline, 12 weeks and 9 months follow-up. The study period extends from August 2016 to May 2018. Recruitment occurred in three phases, corresponding with the delivery of three 12-week HAT TRICK sessions: phase 1 recruitment period occurred in November 2016; phase 2 recruitment period occurred in January 2017; and phase 3 recruitment will begin in August 2017. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram for the HAT TRICK protocol. Figure 2 provides the SPIRIT figure (please see online supplementary file 1 for SPIRIT Checklist).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of HAT TRICK protocol.

Figure 2.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials figure.

bmjopen-2017-016940supp001.pdf (131.3KB, pdf)

Study population, eligibility and recruitment

A total of 60 participants (20 participants × three groups) were recruited for this feasibility trial. This sample size is appropriate for feasibility trials which aim to provide an estimate of the parameters (ie, identifying/recruiting participants; practicality of delivery, SD of a primary outcome measure to estimate sample size) needed to design and conduct a sufficiently powered RCT.22 38 39 To be eligible for the study, participants had to be men over the age of 35 years; reside in the Okanagan Region of British Columbia, Canada; accumulate less than 150 min of PA per week; have a body mass index of over 25 kg/m2 and have a pant waist size of 38’ or greater. It was not a requirement of the programme to be able to skate or play hockey.

A variety of recruitment strategies were used, including: (1) communication avenues via the Kelowna Rockets Hockey Team (eg, poster advertising at home games, Rockets website, newsletters to season tickets holders, game day intercom announcements, recruitment/information booth at home games); (2) local media, including print newspaper and television and radio broadcasts; (3) email and print communication via local male-dominated community organisations (eg, Okanagan Men’s Shed); (4) social media, including Facebook, Castanet, Kijiji and Kelowna Now (community events website) and (5) poster advertisements at local community centres, ice hockey arenas, coffee shops, pubs and bars, and large hardware and automotive commercial entities (eg, Canadian Tire). Prior to groups 2 and 3, word of mouth was an additional recruitment strategy. Lastly, a project-specific website (www.hattrick.ok.ubc.ca) with additional information about the programme, including eligibility criteria and how to sign up, was also used to recruit participants.

Interested individuals were encouraged to contact the research team to confirm their eligibility. Those confirmed eligible were asked to complete a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q+),40 a medical screening tool which has been recommended for use in exercise-related interventions and RCTs.41 All completed PAR-Q+ were reviewed by a Certified Exercise Physiologist42 and individuals who required further medical screening were informed and invited to gain medical clearance from a general medical practitioner (ie, family doctor) in order to participate in the study. Individuals were accepted on a ‘first-come, first-served’ basis with additional individuals being placed on a wait-list and contact list for the next available session.

HAT TRICK intervention

HAT TRICK is a term synonymous with the achievement of a single hockey player scoring three goals in one hockey game. Although the term has its origins in hockey, it is also used in other sports. For example, a soccer player who scores three goals in one game or a football player who scores three touchdowns in one game may also claim that they achieved a ‘hat trick’. Thus, the HAT TRICK programme follows this same logic and focuses on three goals including enhancing PA, healthy eating and social connectedness. The programme was tailored for men using evidence-based research concerning men’s health behaviours27 43 and was guided by theoretical underpinnings associated with behavioural change, specifically incorporating components of the social cognitive theory,44 45 self-determination theory46 and masculinities.14 17 It was also informed by formative consultations with the men, previously conducted by the research team.23 47 Gender-related strategies found to be successful in influencing men’s health behaviours were integrated into the design of the programme including men’s preferences for activity-based approaches, self-monitoring and friendly competition, while providing space for male camaraderie to foster group support, normalise practices related to health and mobilise men in regaining fitness and valued masculine identities and activities.14 17 All resources were consistent with a masculine look and feel, and they provided clear, positive and direct messaging around PA, healthy eating and social connectedness.43 48 For example, consideration was given to the use of colours (eg, dark tones and stark contrasts), images (eg, average men performing PA), language (eg, ‘power foods’) and tone (eg, ‘I don’t need to eat like a rabbit or live at the gym to improve my health’).

HAT TRICK consists of 12 weekly, 90 min face-to-face group sessions delivered at the local hockey arena, the home facility to the Kelowna Rockets. Each group session included a ‘locker room’ component with an ice hockey related theme used to frame health-related education and information regarding PA, healthy eating and behavioural change techniques (ie, goal setting, self-monitoring, social support), while simultaneously promoting enjoyment and increased social connectedness through an interactive and informal style of learning. For instance, to enhance social connectedness, facilitators aimed to foster a sense of teamwork and camaraderie among the men through group activities and competition. Men were encouraged to share contact information and meet outside of the programme as well as foster friendly competition by challenging each other to meet their PA and healthy eating goals. Participants were introduced to a variety of activities and guided through a progressive (ie, increase duration and intensity over time) PA programme within the facility using the team gym, the concession loop and spectator stands. Weekly PA and healthy eating challenges were introduced to encourage men to integrate what they learnt to their daily life.49–51 Table 1 provides a detailed description of the weekly locker room content, PA and challenges provided to the men.

Table 1.

Weekly outline of HAT TRICK

| Locker room education | Group physical activity | Weekly challenge |

| Week 1: Pre game | ||

|

|

On every day this week:

|

| Week 2: Face off | ||

|

|

On at least 3 days of the week:

|

| Week 3: Power play | ||

|

|

On at least 3 days of the week:

|

| Week 4: Tic tac toe | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 5: Long change | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 6: Neutral zone | ||

|

|

On at least 3 days of the week:

|

| Week 7: Penalty kill | ||

|

|

On at least 3 days of the week:

|

| Week 8: Odd man rush | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 9: Icing | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 10: Fast break | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 11: Set play | ||

|

|

On at least 5 days of the week:

|

| Week 12: He shoots, he scores! | ||

|

|

Be HAT TRICK healthy. Keep working towards your goals and making small lifestyle changes |

In the initial deliveries, HAT TRICK was facilitated by research personnel trained in health promotion and behavioural change techniques. However, it is anticipated that for future delivery of the programme, external facilitators such as fitness professionals with relevant certifications (eg, Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology Certified Personal Trainer, British Columbia Recreation and Parks Association Personal Trainer) or other accredited local health professionals (eg, nutrition specialists, physical therapists), as well as individuals who have previously gone through the programme, will be trained to deliver the programme. In addition, hockey team personnel and community experts were invited as guest speakers/presenters for selected sessions. For example, the Rockets athletic therapist was brought in to lead a strength training session and the Rockets nutritionist specialist was a guest presenter for some of the nutrition education sessions. Community health professionals (eg, fitness trainers, physiotherapist) were also involved in leading some of the group sessions. For instance, qualified local fitness professionals led the men through a circuit training session and martial arts type workouts, and a local chef assisted with presenting and discussing healthier food options when ordering from restaurant menus. Including team ‘insiders’ and local professionals (ie, Rockets personnel) provided a variety of content and activities for the men, potentially helping to build community capacity and buy-in, which is vital to future dissemination and sustainability.

All participants were provided with the HAT TRICK ‘Playbook’, a print resource manual that further summarised the key messages and signposts the resources to draw on over 12-week programme. The ‘Playbook’ is divided into 12 weeks and corresponds with each weekly theme of HAT TRICK, as outlined in table 1. It contains educational information, expressed in simple terms using hockey-related metaphors, concerning healthy eating (ie, information about macronutrients, portion sizes, etc) and active living (ie, barriers and benefits to PA, being active at home, etc), as well as strategies for weight management and behavioural change, such as information concerning social support, self-monitoring, goal setting and relapse prevention. To assist with self-monitoring, participants were provided with a Fitbit Charge HR and PA and dietary tracking logs which are embedded in the ‘Playbook’. During each week of the programme, men were encouraged and challenged to increase their step count (in graduate increments) and non-walking PA, as well as to engage in healthy eating (eg, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption) and record these activities in their ‘Playbook’ tracking logs.

Outcome measures

Quantitative and qualitative data collection methods were used to assess outcome and feasibility measures. All assessments took place at the same facility where HAT TRICK was delivered and occurred at baseline (1 week prior to the start of the programme) and at 12 weeks (completion of the programme) and will occur again at 9 months follow-up (post baseline). Participants who were unable to attend the measurement session were invited to complete measures at an agreed on time in the Physical Health and Activity Behaviour Lab at the University of British Columbia or at an alternative location such as their home. All measures are described in further detail below. In addition, table 2 provides a summary of measures and data collection time points.

Table 2.

Summary of measures and data collection time points

| Measures | Methods for data collection | Data collection time points |

| Demographics | Age, ethnicity, education, occupation, income, marital status, comorbidities | 0 (baseline only) |

| Anthropometrics | Height, weight, waist circumference | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Physiological measures | Blood pressure, heart rate | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| PA levels | ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer (over a 7-day period) | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months | |

| Sedentary behaviour | ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer (over a 7-day period) Marshall Sitting Questionnaire (MSQ) |

0, 12 weeks and 9 months 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Dietary behaviour | The Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education Questionnaire (DINE) | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Other health behaviours | 7-day Alcohol recall | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Smoking and tobacco use | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months | |

| Sleep habits | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months | |

| Psychological and physical well-being | SF-12 V.2 Health Survey | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months |

| Male Depression Risk Scale (MDRS-22) | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months | |

| Abbreviated Duke Social Support Index (DSSI-11) | 0, 12 weeks and 9 months | |

| Programme satisfaction/acceptability | Satisfaction/acceptability questionnaire | 12 weeks (postintervention only) |

| Semistructured telephone interview with participants | 12 weeks (postintervention only) |

Demographics, anthropometrics and physiological measures.

PA, physical activity.

As part of the self-report questionnaire, participants were asked to report demographic variables including: date of birth, ethnic background, level of education, marital status, chronic disease conditions, main activity, occupation and household income. Height (centimetre), weight (kilogram), waist circumference (centimetre), blood pressure (millimetre of mercury) and heart rate (beats per minute) were measured by a research team member, trained to a standard protocol, at all assessment sessions. Weight and height were measured with the participant standing normally, with feet together and head in the Frankfort plane, using Seca 700 mechanical balance scales and a Seca 220 measuring rod (Seca, Hamburg). Using the National Institutes of Health protocol,52 waist circumference was measured on the transverse plane at the top of the iliac crest using a measurement tape. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured two times at 2 min intervals with a Life Source Digital Deluxe One Step Blood Pressure Monitor. Participants were asked to sit quietly for 5 min prior to the first measurement. Blood pressure was measured on the left arm with forearm on a table, palm of the hand facing up. Participants were asked to rest the arm comfortably at heart level, sitting with their back against the chair, legs uncrossed.

Physical activity

PA was assessed objectively using an ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensacola, Florida, USA) during all waking hours over 7 days. The accelerometers were initialised to record steps, inclination and acceleration counts in triaxial mode, using 60 s epochs.53 54 Participants were instructed to wear the accelerometer above their right hip and in-line with their right knee facing up and to remove it during sleeping hours or for any activities where water may be involved. The ActiGraph GT3X is considered the ‘gold standard’ measure of PA in adults55 and has shown validity and reliability compared with other commercial devices.56 57 Established cut-off points were used to calculate daily minutes of moderate (2691–6166 counts/min) and vigorous (>6167 counts/min) PA while controlling for the number of days the accelerometer was worn.56 Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) will be calculated as a sum score of weekly minutes in MVPA. Data will be included in the analyses if there are no extreme counts (>20 000) and if data are available for at least 600 min wear time per day on 5 days. Participants with invalid data were asked to wear the activity monitor for a further 7 days.

PA was also assessed by self-report using a modified version of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ).58 Participants were asked to indicate the frequency and type of intensity (ie, light, moderate, vigorous) of their daily PA per week and the duration (min) of these sessions.58 All responses will be converted to minutes and calculated in accordance with the metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes method.59 A cut-off point of ≥600 MET minutes will then be used to dichotomise participants as ‘adequately active for health benefit’ or ‘inadequately active’.59 60 The GLTEQ has shown good validity and reliability across a number of populations and settings.61–63

Sedentary behaviour

Accelerometers were also be used to objectively assess sedentary behaviour using a 30 s epoch. Sedentary time will be determined as <100 counts/min, adjusted for non-wear time operationalised as at least 60 min of consecutive zeros.54 In addition, sedentary behaviours were assessed by self-report using the Marshall Sitting Questionnaire (MSQ).64 The MSQ assesses time spent sitting on weekdays and weekend days at work, travelling and at home. Data from the sitting time questionnaire will be used to create an estimate of total weekday and weekend-day sitting times (min/day) by summing the time reported in each domain.64 This measure has demonstrated reliability and validity in the adult population.64

Dietary behaviours

Dietary behaviours were assessed by the Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education (DINE) questionnaire,65 a short 19-item questionnaire providing a measure of frequency of intake of different food types (ie, fruits and vegetables) and macronutrients over the last 7 days. Composite scores will be calculated in accordance with the DINE protocol used for total fat intake and total fibre intake, with higher scores indicating greater consumption.65 This validated instrument65 is considered to be an acceptable alternative to more detailed diet recall questionnaires and food dairies, and it was chosen for this particular study as it focuses on food types (ie, fruits and vegetables) associated with chronic disease prevention and management.66 67

Other health-related behaviours

Smoking and tobacco use, alcohol consumption and sleep habits were assessed via self-report questions.68 Smoking status was measured using a single question, wherein participants identify as a regular smoker (daily), occasional smoker (once in a while), ex-smoker or non-smoker. Occasional and regular smokers were asked to report their smoking habits and quit attempts using standardised questions.68

Alcohol intake was measured using a 7-day alcohol recall.69 Participants were asked to consider the previous 7 days and report the number of pints of beer/cider, glasses of wine, glasses of fortified wine (eg, Port), measures of spirits and any other alcoholic beverages consumed each day.

Participants’ sleeping habits were reported through average hours of sleep on a typical night.70 Descriptive measures related to speaking with a doctor or health professional about having difficulty sleep and being diagnosed with a sleep disorder were also collected.70

Risk of depression

Risk of depression was assessed using the Male Depression Risk Scale (MDRS-22).71 This is a 22-item Likert scale questionnaire ranging from 0 (not at all) to 7 (almost always). Participants were asked to think back over the last month and respond to each item considering how often it applies. The MDRS-22 provides a total score via the summation of all 22 items and six subscale scores that follow six symptom domains including: emotional suppression, drug use, alcohol use, somatic symptoms, risk taking and anger and aggression. A higher score indicates a greater risk of depression. The MDRS-22 has demonstrated validity and reliability among men.71 72

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was assessed using the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12).73 The SF-12 was developed as a shorter alternative to the SF-36,74 and it includes 12 questions and eight physical and mental health dimension scales including; physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function role emotional and mental health.73 Scoring for this survey includes precoded numeric values that are assigned to each of the eight scales and then scored from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better health.75 The SF-12 is one of the most widely used HRQoL evaluation tools and has been shown to be valid and reliable in a number of populations.76–79

Social support

The abbreviated Duke Social Support Index (DSSI-11)80 was used to assess perceived social support. The DSSI is an 11-item questionnaire comprising two subscales: social interaction (four items) and social satisfaction (seven items), measured on a four-point Likert scale. The social interaction subscale asks questions regarding the number of social interactions an individual has had within the past week (eg, How many times during the past week did you spend time with someone who does not live with you?). The social satisfaction subscale asks about the subjective quality of these relationships (eg, When you are talking with your family or friends, do you feel you are being listened to?). The social interaction scale ranges from 4 to 12 and the social satisfaction subscale ranges from 6 to 18; thus, the total score for the DSSI-11 ranges from 10 to 30 (combination of social interactions and social satisfaction scores, with social satisfaction reverse scored before summation) with higher scores indicating a stronger perception of social support.80 The DSSI-11 has been shown to be valid and reliable in adult populations and reported to be useful for measuring social support in community-based epidemiological studies.81–84

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses will be completed and presented as means and SD for continuous variables and as frequencies and proportions for categorical data. Data analysis of outcome variables including estimates of change in PA, sedentary behaviour, dietary behaviours, smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep habits, risk of depression, HRQoL and social support will be examined using a within-subjects, repeated-measures analysis of variance. The level of significance (α) will be set at 0.05. As the primary outcome is feasibility, it is not appropriate to perform a power calculation. All analyses will be conducted using IBM SPSS statistics 23.

Programme feasibility and analysis

At 12 weeks (postintervention), all participants will complete a programme satisfaction/acceptability questionnaire. Participants will be asked several Likert scale questions as well as open-ended response questions relating to their experience and satisfaction with the programme design, content, resources and logistics concerning programme implementation (ie, day and time of sessions, structure of sessions, facility where programme was delivered). To inform future requirement strategies, data will also be collected from website usage patterns (Google Analytics: frequencies, means, etc) as they relate to key time points during the programme (eg, media releases) as well as using paper-based questions regarding how/where participants heard about the programme. Programme-related statistics, including participant attendance, number of guest presenters and metrics concerning programme inquiries, participant communications and follow-ups, will also be collected.

Semistructured telephone interviews will be undertaken with a subsample of participants (n=30) to gain further insight concerning satisfaction and acceptability of HAT TRICK and to understand the challenges/enablers associated with design and implementation of the programme, including feasibility parameters such as recruitment, attendance, adherence and acceptability of the programme and content. Participants will be purposefully selected from each of the three HAT TRICK groups to include men reporting a range of feasibility and programme outcomes. These individuals will include those who have completed the programme (ie, completed baseline and 12-week follow-up assessment periods) and have attended at least 50% of the sessions (ie, 6 of 12 weekly 90 min sessions). Data collection and analysis will occur simultaneously in three phases as the HAT TRICK programme is implemented. Interview questions will be refined as data collection progresses to address gaps identified in the analysis as well as expand on and verify emerging themes. Data from the interviews will be audio recorded (with participants’ permission) and transcribed verbatim with all identifiable information removed. Data will be analysed using thematic content analysis85 to explore participant satisfaction and enjoyment and to identify challenges experienced during programme implementation as well as factors that may have facilitated implementation. To enhance rigour, at least two members of the research team will independently code participant responses into relevant subthemes. Once all coding has been completed, subthemes will be discussed among the two research team members to ensure that bias is minimised. Any disagreements or concerns that may arise during the analysis will be presented at this time and further discussion will be carried out with the research team until consensus is reached.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this trial was obtained from the University of British Columbia Okanagan Behavioural Research Ethics Board (reference no H1600736). Participants provided informed consent (please see online supplementary file 2) and medical clearance prior to all baseline assessments. Participants were also informed that they may withdraw from the study at any time, for any reason, without consequence. All personal data will be coded and handled with confidentiality.

bmjopen-2017-016940supp002.pdf (336.9KB, pdf)

Study findings will be disseminated widely through national and international academic meetings, through peer-reviewed publication and by web-based activities (eg, podcasts, research webinars). In addition, these findings will also be disseminated through social media (eg, Facebook, Twitter), plain language summaries to participants, summary briefings to local stakeholders and government agencies and co-delivered (ie, researcher–participants) community presentations.

Discussion

Engaging men in health promoting behaviours, such as PA and healthy eating, can be challenging. Men have often been regarded as ‘hard to reach’ in terms of health promotion programmes with linkages being made to some masculine ideals as contributing to men’s estrangement from their health. This is further supported by the research which has suggested that many men are reticent to attend health promotion education sessions, disinterested in information concerning disease prevention and estranged from professional healthcare services86 87 although more recent research is beginning to challenge such stereotypes. Some researchers suggest that these ‘traditional’ patterns are implicated in Western men’s shorter life expectancy compared with women and high morbidity rates associated with chronic disease.88 89 Thus, men are a population that would benefit from effective targeted programmes to engage them in healthy lifestyle behaviours, including PA and healthy eating. To reach and engage men, innovative approaches that are aligned with a range of masculinities (eg, strength, toughness, risk-taking and skill in PA) as well as provide safe male spaces to promote trust and normalise men’s efforts to change their health behaviours show promise in garnering significant success in advancing the health of men and their families.12 13 19 26 30

HAT TRICK was designed to address these specific elements by creating an evidence-based programme that employed men-friendly strategies to fully engage men’s participation, including; aligning with an elite male sports team (ie, Kelowna Rockets), promoting friendly competition and delivering the programme in a familiar ‘place’ (ie, hockey arena and surrounding male-friendly community venues) where men ordinarily gather and connect with others (ie, male facilitators and male only participants) who share similar interests. Appealing to these well-known masculine values and norms including friendly competition and catering to methods and modes of delivery that recognise gender differences have been successful approaches to men-centred PA and healthy eating programmes.12 26 27 47

Another promising aspect of HAT TRICK is its potential to be transferred across a number of male populations and settings, thus further increasing its reach to a large proportion of men. In part, HAT TRICK is based on the successful FFIT intervention,27 30 which was designed to engage overweight Scottish men in weight management and healthy living programme by capitalising on men’s team loyalty and love of the game of soccer. FFIT was specifically developed within a context that supports masculine ideals, encompassing a look and feel that appeals to many men.22 32 HAT TRICK used these same principles but altered the context of delivery by developing the programme to fit with the national sports obsession of Canadian men, ice hockey. Specifically, the programme’s name (HAT TRICK), logo design, resources and content are all influenced by the sport of ice hockey. Although this particular programme was designed to appeal to male Canadian ice hockey fans, the unique aspect of this model is that it can be easily modified to appeal to male fans of other sports or activities. For instance, the same model has been recreated to appeal to Rugby fans in the UK. The Rugby Fans in Training35 study (and subsequently Premiership Rugby’s Move Like a Pro programme) aimed to test the FFIT model in the English professional rugby club setting and to enhance long-term weight loss and lifestyle change for men in the UK. In North America, a similar approach could be transferable to other popular sports including gridiron football, basketball and baseball, all of which exist within professional leagues that have a strong male fan base.

Although HAT TRICK can be recreated and transferred to suit fans of a variety of sports, we do acknowledge that there is a great diversity of men within Canada (eg, new immigrant men, older age men, gay men, men from remote areas) who may have other interests beyond sport. Thus, prior to undertaking refinements and restructuring the programme, formative evaluations should be undertaken with these specific male groups in order to gain further knowledge concerning local, regional and global masculine values and norms.24

In conclusion, given the limited published research for effective and feasible approaches to men’s health promotion, but the promise shown by programmes such as FFIT, the results of this feasibility study will serve as a valuable platform to guide future work. There also seems to be great opportunity for sustainability and scalability of the HAT TRICK programme based on its transferability and the thoughtful deliberate formal evaluation of this intervention.

Trial status

The trial was registered on 3 August 2016. Recruitment for this study began in December 2016 and is ongoing until September 2017.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CMC, JLB, JLO, STJ and KH conceived the project and procured the project funding. CMC is leading the coordination of the trial. CMC, JLB, JLO, STJ, KH and SLG contributed to the study design. PS is managing the trial, including data collection, with assistance from KMF and RP. CMC, PS, KMF and RP drafted the manuscript and all authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research is being funded by the Canadian Cancer Society (grant no 704230). KH is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU12017/12) and the Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU12).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board (reference no H16-00736).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets analysed during the current trial will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Lee CD, Sui X, Hooker SP, et al. Combined impact of lifestyle factors on cancer mortality in men. Ann Epidemiol 2011;21:749–54. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shiroma EJ, Sesso HD, Lee IM. Physical activity and weight gain prevention in older men. Int J Obes 2012;36:1165–9. 10.1038/ijo.2011.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kohl HW. 3rd, Craig CL, Lambert EV, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet 2012;380:294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nunan D, Mahtani KR, Roberts N, et al. Physical activity for the prevention and treatment of major chronic disease: an overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2013;2:56. 10.1186/2046-4053-2-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colley RC, Garriguet D, Janssen I, et al. Physical activity of Canadian children and youth: accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian health measures survey. Health Rep 2011;22:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, et al. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med 2004;27:107–16. 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baker AH, Wardle J. Sex differences in fruit and vegetable intake in older adults. Appetite 2003;40:269–75. 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00014-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bélanger-Ducharme F, Tremblay A. Prevalence of obesity in Canada. Obes Rev 2005;6:183–6. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baker P. Current issues in men’s health. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health 2012;3:19–21. 10.1002/tre.241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sinclair A, Alexander HA. Using outreach to involve the hard-to-reach in a health check: what difference does it make? Public Health 2012;126:87–95. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Young MD, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, et al. Effectiveness of male-only weight loss and weight loss maintenance interventions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2012;13:393–408. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00967.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski JL, et al. Male inclusion in randomized controlled trials of lifestyle weight loss interventions. Obesity 2012;20:1234–9. 10.1038/oby.2011.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1385–401. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Courtenay WE. Making health manly: norms, peers, and men’s health : Cohen L, Chavez V, Chehimi S, Prevention is primary; Strategies for community wellbeing. San Francisco, CA: jossey-bass, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gough B. Try to be healthy, but don’t forgot your masculinity: deconstructing men’s health discourse in the media. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2476–88. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robertson S. Understanding men and health: masculinities, identities and well-being. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sloan C, Gough B, Conner M. Healthy masculinities? How ostensibly healthy men talk about lifestyle, health and gender. Psychol Health 2010;25:783–803. 10.1080/08870440902883204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cormie P, Oliffe JL, Wootten AC, et al. Improving psychosocial health in men with prostate cancer through an intervention that reinforces masculine values—exercise. Psychooncology 2016;25 10.1002/pon.3867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gough B. ‘Real men don’t diet’: an analysis of contemporary newspaper representations of men, food and health. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:326–37. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pringle A, Zwolinsky S, McKenna J, et al. Health improvement for men and hard-to-engage-men delivered in English Premier League football clubs. Health Educ Res 2014;29:503–20. 10.1093/her/cyu009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gray CM, Hunt K, Mutrie N, et al. Football fans in training: the development and optimization of an intervention delivered through professional sports clubs to help men lose weight, become more active and adopt healthier eating habits. BMC Public Health 2013;13:232. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Sharp P, et al. Healthy eating and active living: rural-based working men’s perspectives. Am J Mens Health 2015 10.1177/1557988315619372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caperchione CM, Sharp P, Bottorff JL, et al. The POWERPLAY workplace physical activity and nutrition intervention for men: study protocol and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;44:42–7. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson ST, Stolp S, Seaton C, et al. A men’s workplace health intervention: results of the POWERPLAY program pilot study. J Occup Environ Med 2016;58:765–9. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caperchione CM, Stolp S, Bottorff JL, et al. Changes in men’s physical activity and healthy eating knowledge and behavior as a result of program exposure: findings from the workplace POWERPLAY program. J Phys Act Health 2016;13:1364–71. 10.1123/jpah.2016-0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wyke S, Hunt K, Gray CM, et al. Football fans in training (FFIT): a randomised controlled trial of a gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for men—end of study report. Public Health Res 2015;3:1–130. 10.3310/phr03020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mason OJ, Holt R. Mental health and physical activity interventions: a review of the qualitative literature. J Ment Health 2012;21:274–84. 10.3109/09638237.2011.648344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brady AJ, Perry C, Murdoch DL, et al. Sustained benefits of a health project for middle-aged football supporters, at Glasgow Celtic and Glasgow Rangers Football Clubs. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2696–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hunt K, Wyke S, Gray CM, et al. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1211–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62420-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gill DP, Blunt W, De Cruz A, et al. Hockey fans in training (Hockey FIT) pilot study protocol: a gender-sensitized weight loss and healthy lifestyle program for overweight and obese male hockey fans. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1096. 10.1186/s12889-016-3730-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt K, McCann C, Gray CM, et al. “You’ve got to walk before you run”: positive evaluations of a walking program as part of a gender-sensitized, weight-management program delivered to men through professional football clubs. Health Psychol 2013;32:57–65. 10.1037/a0029537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bunn C, Wyke S, Gray CM, et al. ‘Coz football is what we all have’: masculinities, practice, performance and effervescence in a gender-sensitised weight-loss and healthy living programme for men. Sociol Health Illn 2016;38:812–28. 10.1111/1467-9566.12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Nassau F, van der Ploeg HP, Abrahamsen F, et al. Study protocol of European fans in training (EuroFIT): a four-country randomised controlled trial of a lifestyle program for men delivered in elite football clubs. BMC Public Health 2016;16:598 10.1186/s12889-016-3255-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gray CM, Brennan G, MacLean A, et al. Can professional rugby clubs attract english male rugby supporters to a healthy lifestyle programme: the Rugby Fans in Training (RuFIT) study 2013–14. Eur J Public Health 2014;24(suppl_2):166. 10.1093/eurpub/cku166.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Canadian Hockey League. Canadian Hockey League. 2017. http://chl.ca/ (accessed 25 Feb 2017).

- 37. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, et al. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:67. 10.1186/1471-2288-10-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Physial Activity and Readiness Questionnaire for everyone: PAR-Q+. 2012. http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/parqplussept2011version_all.pdf (accessed 21 Feb 2017).

- 41. Duncan MJ, Rosenkranz RR, Vandelanotte C, et al. What is the impact of obtaining medical clearance to participate in a randomised controlled trial examining a physical activity intervention on the socio-demographic and risk factor profiles of included participants? Trials 2016;17:580. 10.1186/s13063-016-1715-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP). 1967. http://www.csep.ca/en/about-csep/about-the-canadian-society-for-exercise-physiology (accessed 10 Feb 2017).

- 43. Bottorff JL, Seaton CL, Johnson ST, et al. An updated review of interventions that include promotion of physical activity for adult men. Sports Med 2015;45:775–800. 10.1007/s40279-014-0286-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bandura A. Social foundation of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:248–87. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caperchione CM, Vandelanotte C, Kolt GS, et al. What a man wants: understanding the challenges and motivations to physical activity participation and healthy eating in middle-aged Australian men. Am J Mens Health 2012;6:453–61. 10.1177/1557988312444718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taylor PJ, Kolt GS, Vandelanotte C, et al. A review of the nature and effectiveness of nutrition interventions in adult males—a guide for intervention strategies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:13. 10.1186/1479-5868-10-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Verdonk P, Seesing H, de Rijk A, masculinity D. Doing masculinity, not doing health? A qualitative study among dutch male employees about health beliefs and workplace physical activity. BMC Public Health 2010;10:712 10.1186/1471-2458-10-712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. George ES, Kolt GS, Duncan MJ, et al. A review of the effectiveness of physical activity interventions for adult males. Sports Med 2012;42:281–300. 10.2165/11597220-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morgan PJ, Collins CE, Plotnikoff RC, et al. Efficacy of a workplace-based weight loss program for overweight male shift workers: the Workplace POWER (Preventing Obesity Without Eating like a Rabbit) randomized controlled trial. Prev Med 2011;52:317–25. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. National Institute of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overwieght and obesity in adults-the eivdence report. Washington, DC, 1998:56–94. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:777–81. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:181–8. 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kelly LA, McMillan DG, Anderson A, et al. Validity of actigraphs uniaxial and triaxial accelerometers for assessment of physical activity in adults in laboratory conditions. BMC Med Phys 2013;13:5. 10.1186/1756-6649-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J Sci Med Sport 2011;14:411–6. 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vanhelst J, Mikulovic J, Bui-Xuan G, et al. Comparison of two ActiGraph accelerometer generations in the assessment of physical activity in free living conditions. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:187. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985;10:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brown WJ, Bauman AE. Comparison of estimates of population levels of physical activity using two measures. Aust N Z J Public Health 2000;24:520–5. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Plotnikoff RC, Johnson ST, Loucaides CA, et al. Population-based estimates of physical activity for adults with type 2 diabetes: a cautionary tale of potential confounding by weight status. J Obes 2011;2011:1–5. 10.1155/2011/561432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Godin G, Jobin J, Bouillon J. Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: a concurrent validity study. can J Public Health . Sep 1986;77:359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jacobs DR, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, et al. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:81–91. 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hyde AL, Elavsky S, Doerksen SE, et al. The stability of automatic evaluations of physical activity and their relations with physical activity. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2012;34:715–36. 10.1123/jsep.34.6.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Marshall AL, Miller YD, Burton NW, et al. Measuring total and domain-specific sitting: a study of reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1094–102. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roe L, Strong C, Whiteside C, et al. Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Fam Pract 1994;11:375–81. 10.1093/fampra/11.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cole JA, Gillespie P, Smith SM, et al. Using postal questionnaires to evaluate physical activity and diet behaviour change: case study exploring implications of valid responder characteristics in interpreting intervention outcomes. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:725. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. John JH, Ziebland S, Yudkin P, et al. Effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on plasma antioxidant concentrations and blood pressure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1969–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)98858-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Diemert L, Kueller-Olaman R, Schwartz R, et al. ; Data Standards for Smoke-free Ontario Smoking Cessation Service Providers: core Indicators and Questions for Intake and Follow-up of adult respondents. Toronto, ON: Ontario Tobacco Research Unit, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Emslie C, Lewars H, Batty GD, et al. Are there gender differences in levels of heavy, binge and problem drinking? Evidence from three generations in the west of Scotland. Public Health 2009;123:12–14. 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Sleep Disorders: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rice SM, Fallon BJ, Aucote HM, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: furthering the assessment of depression in men. J Affect Disord 2013;151:950–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rice SM, Fallon BJ, Aucote HM, et al. Longitudinal sex differences of externalising and internalising depression symptom trajectories: implications for assessment of depression in men from an online study. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2015;61:236–40. 10.1177/0020764014540149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Healty Summary Scales: a user’s Manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Quality Metric Incorporated: Lincoln, RI, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jenkinson C, Chandola T, Coulter A, et al. An assessment of the construct validity of the SF-12 summary scores across ethnic groups. J Public Health Med 2001;23:187–94. 10.1093/pubmed/23.3.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Burdine JN, Felix MR, Abel AL, et al. The SF-12 as a population health measure: an exploratory examination of potential for application. Health Serv Res 2000;35:885–904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jakobsson U. Using the 12-item short form health survey (SF-12) to measure quality of life among older people. Aging Clin Exp Res 2007;19:457–64. 10.1007/BF03324731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wee CC, Davis RB, Hamel MB. Comparing the SF-12 and SF-36 health status questionnaires in patients with and without obesity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:11. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK, et al. Abbreviating the Duke social support index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics 1993;34:61–9. 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71928-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Goodger B, Byles J, Higganbotham N, et al. Assessment of a short scale to measure social support among older people. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:260–5. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Powers JR, Goodger B, Byles JE. Assessment of the abbreviated Duke social support index in a cohort of older Australian women. Australas J Ageing 2004;23:71–6. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2004.00008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ebeling-Witte S, Frank ML, Lester D, Shyness LD. Shyness, Internet use, and personality. Cyberpsychol Behav 2007;10:713–6. 10.1089/cpb.2007.9964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pachana NA, Smith N, Watson M, et al. Responsiveness of the Duke social support sub-scales in older women. Age Ageing 2008;37:666–72. 10.1093/ageing/afn205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lee C, Owen GR. The psychology of men'’s health. Philadelphia: Open Uiversity Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Deeks A, Lombard C, Michelmore J, et al. The effects of gender and age on health related behaviors. BMC Public Health 2009;9:213 10.1186/1471-2458-9-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, et al. Are men shortchanged on health? Perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:475–87. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Salomon JA, Wang H, Freeman MK, et al. Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2144–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61690-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016940supp001.pdf (131.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016940supp002.pdf (336.9KB, pdf)