Abstract

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in pragmatic trials methodology. As a result, tools such as the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 (PRECIS-2) are being used prospectively to help researchers design randomised controlled trials (RCTs) within the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. There may be value in applying the PRECIS-2 tool retrospectively in a systematic review setting as it could provide important information about how to pool data based on the degree of pragmatism.

Objectives

To investigate the role of pragmatism as a source of heterogeneity in systematic reviews by (1) identifying systematic reviews with meta-analyses of RCTs that have moderate to high heterogeneity, (2) applying PRECIS-2 to RCTs of systematic reviews, (3) evaluating the inter-rater reliability of PRECIS-2, (4) determining how much of this heterogeneity may be explained by pragmatism.

Methods

A cross-sectional methodological review will be conducted on systematic reviews of RCTs published in the Cochrane Library from 1 January 2014 to 1 January 2017. Included systematic reviews will have a minimum of 10 RCTs in the meta-analysis of the primary outcome and moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I2≥50%). Of the eligible systematic reviews, a random selection of 10 will be included for quantitative evaluation. In each systematic review, RCTs will be scored using the PRECIS-2 tool, in duplicate. Agreement between raters will be measured using the intraclass correlation coefficient. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression will be used to evaluate how much variability in the primary outcome may be due to pragmatism.

Dissemination

This review will be among the first to evaluate the PRECIS-2 tool in a systematic review setting. Results from this research will provide inter-rater reliability information about PRECIS-2 and may be used to provide methodological guidance when dealing with pragmatism in systematic reviews and subgroup considerations. On completion, this review will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

Keywords: pragmatic trials, methodological review, systematic reviews, heterogeneity, meta-regression, statistics and research methods, PRECIS-2

Strengths and limitations of this study.

One of the first reviews to apply the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 (PRECIS-2) in a systematic review setting.

PRECIS-2 scoring will be performed independently, in duplicate.

Included systematic reviews will be randomly selected as a means to reduce bias.

Only Cochrane systematic reviews will be considered.

Other factors may contribute to heterogeneity that are not included in this review.

Introduction

In clinical research, randomised trials are often categorised as either pragmatic or explanatory.1 In broad terms, pragmatic trials are designed to determine the effects of an intervention under the usual or real-world conditions in which it will be applied whereas explanatory trials are designed to determine the effects of an intervention under ideal or controlled circumstances.2 The distinction between pragmatic and explanatory trials was first introduced by Schwartz and Lellouch nearly half a century ago.3 In their seminal article, they described differing approaches to pragmatic and explanatory trials with the former aimed at clinical decision-making and the latter aimed at understanding treatment effects.3

Interest in pragmatic trials methodology has become widespread in the scientific community, resulting in the development of several tools designed to aid researchers in characterising and designing pragmatic trials. In 2006, Gartlehner et al published a tool to distinguish pragmatic from explanatory trials in an effort to provide authors of systematic reviews a means to quantify generalisability of included studies.4 In 2009, Thorpe et al published the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS) tool which was developed to inform study design rather than a means of classifying trials within systematic reviews.1 The authors discussed the use of a pragmatic-explanatory continuum rather than a dichotomy as Gartlehner et al had proposed4 and as such, a formal scoring system was not developed.1 The PRECIS tool has 10 domains which include key trial design considerations such as participant eligibility, interventions and expertise, follow-up and outcomes, compliance/adherence and analysis.1 The tool was well received on publication and has been cited hundreds of times since its inception in 2009.5 In 2011, Tosh et al used the PRECIS framework to develop the Pragmascope tool, which was designed assess the applicability of randomised controlled trial (RCT) results, according to what was planned at the protocol stage.6 Unlike PRECIS, the Pragmascope had a formal scoring system where each of the 10 PRECIS domains were rated from 1=most explanatory to 5=most pragmatic.6 Scores of 0 were given if there was not enough information to judge a particular domain.6

The PRECIS tool was intended for use at the trial design stage; however, it has been applied a number of times in the systematic review setting in an effort to quantify how pragmatic primary RCTs and systematic reviews are.7 8 This quantification may provide additional guidance for healthcare providers and decision-makers regarding the applicability of the RCTs and systematic reviews in routine practice.7 In cases where PRECIS was applied to systematic reviews, a scoring system was used which ranged from either 0-4, or 1-5 with the lowest number representing a more explanatory RCT or review and the highest number representing a more pragmatic RCT or review.7 8

Koppenaal et al applied a modified version of PRECIS which they called the PRECIS Review tool to two systematic reviews of primary care interventions.7 Independent raters gave scores of 1–5 for each PRECIS domain within a primary RCT; however, they did not pursue an assessment of inter-rater reliability even though rating was performed in duplicate. The authors did discuss noteworthy observations such as the assumption of equal weighting across the 10 domains and that it cannot always provide an assessment of pragmatism that is applicable to multiple settings such as different countries or types of healthcare services.7 Yoong et al applied an adapted version of PRECIS to a systematic review of interventions for preventing obesity in children.8 Independent raters gave scores of 0–4 for each PRECIS domain within a primary RCT and inter-rater reliability was assessed using a weighted kappa which ranged from 0.23 to 0.75, suggesting a wide variation in agreement among the 10 domains.8 The authors developed cut-offs to classify primary RCTs as predominantly explanatory (0 to1.7), combined explanatory/pragmatic (>1.7 to ≤2.2) and mostly pragmatic (>2.2 to 4).8 They explored the impact of study classification on intervention effect sizes by age group (0–5 years, 6–12 years and 13–18 years), and found that pragmatic trials had the smallest effect sizes compared with explanatory trials.8 However, the authors stopped short of exploring the effect of pragmatism on heterogeneity (I2 which was substantial among each age group and overall (I2=79%).9 Yoong et al suggested reporting the results of PRECIS with other subgroup analyses in systematic reviews and discussed the need to further explore the impact of pragmatism across a broad range of systematic review topics and large number of trials.8

While Koppenaal et al and Yoong et al applied modified versions of PRECIS to previously conducted systematic reviews, Witt et al conducted a systematic analysis in trials of acupuncture for lower back pain with the intention of applying the PRECIS tool.10 The authors used a similar scoring system as Koppenaal et al which was performed independently by five raters followed by consensus discussions to resolve disagreements. In addition to using PRECIS, the raters also judged the degree of difficulty of applying PRECIS criteria using a scale from 0 (very easy) to 10 (very difficult).10 These results were presented alongside the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) which ranged from 0.02 to 0.60 (preconsensus) and 0.20 to 1.0 (postconsensus) suggesting a large variation in agreement, even following the resolution of disagreements in PRECIS scoring.10

Interestingly, the domain ‘follow-up intensity’ had the lowest ICC and was judged as ‘difficult’ to score which aligned with the results from Yoong et al where the lowest agreement rating was in the same domain.8 10 Moreover, Witt et al discussed missing information as a limitation of applying PRECIS which appeared as a limitation in both Koppenaal et al and Yoong et al.7 8 10 Nonetheless, despite the limitations, each research group acknowledged that the modification of PRECIS was useful and may provide important insight regarding the quantification of pragmatism at both the RCT and systematic review level.7 8 10

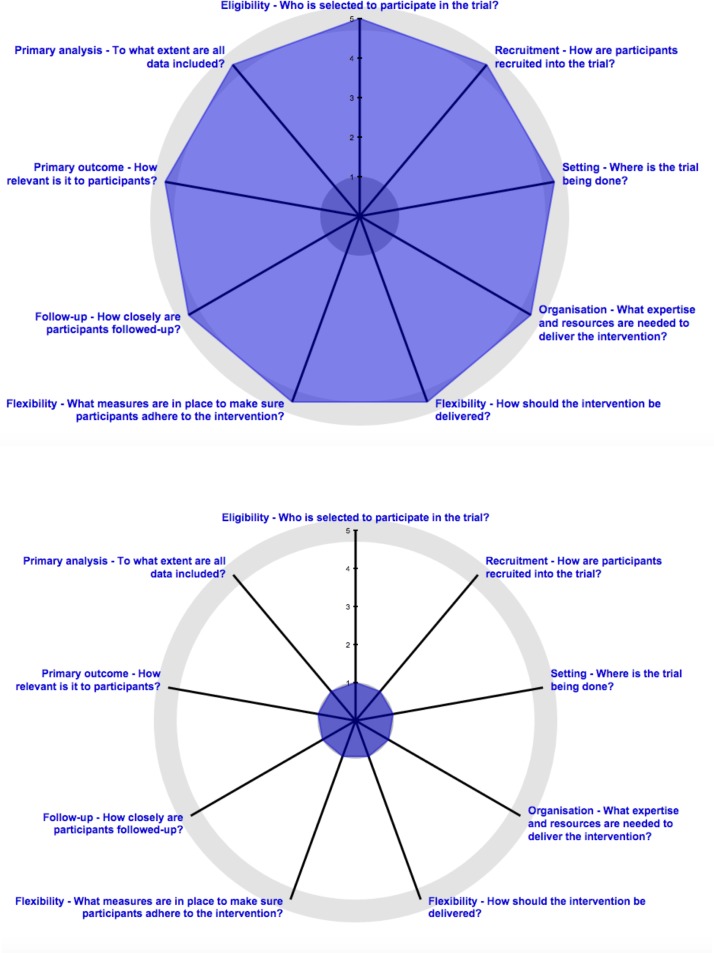

In 2015, a revised version of the PRECIS tool was published by Loudon et al called PRECIS-2 which addressed the weaknesses of the original tool such as unclear inter-rater reliability, lack of a scoring system and redundancy in some PRECIS domains.5 Currently, there are nine domains in the PRECIS-2 tool including eligibility, recruitment, setting, organisation, flexibility (delivery and adherence), follow-up, primary outcome and primary analysis.5 Each domain is scored using a 5-point Likert scale where 1=a very explanatory trial and 5=a very pragmatic trial.5 Similar to the original PRECIS, scores from each domain may be graphically displayed using the PRECIS-2 wheel where points closer to the centre of the wheel depict a more explanatory trial and points at the outer area of the wheel depict a more pragmatic trial (figure 1).5 Studies are rarely entirely pragmatic or explanatory and so one domain may be more or less pragmatic than another.1 While the tool is intended to be used at the design stage of a trial, the authors believe PRECIS-2 may have a role in critical appraisal and systematic reviews.5

Figure 1.

Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 (PRECIS-2) wheels showing a very pragmatic trial with scores of 5 across each of the nine domains (top) and a very explanatory trial with scores of 1 across each of the nine domains (bottom). PRECIS-2 wheels generated at http://www.precis-2.org/.

Very recently, Loudon et al undertook an in depth assessment of inter-rater reliability and discriminant validity of the PRECIS-2 tool.11 Nineteen experienced trialists and methodologists agreed to review 10–15 trial RCT protocols and rate them according to criteria of the nine PRECIS-2 domains.11 Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the ICC which ranged from 0.24 to 0.9411 suggesting diverse agreement, similar to that of Yoong et al and Witt et al. However, the majority of the domains had an ICC >0.65 suggesting substantial agreement with the exception of two out of the nine domains (flexibility-adherence and primary outcome).11 Discriminate validity was assessed using the area under the curve for each domain which ranged from 0.57 to 0.75 suggesting fair discriminant reliability in four out of the nine PRECIS-2 domains (primary outcome, follow-up, flexibility-delivery and primary analysis).11 Further assessment of inter-rater reliability may be beneficial, particularly with the use of main trial publications. Additional assessment would provide inter-rater reliability information for a systematic review setting and complementary information for how PRECIS-2 could be applied when RCT protocols are not available.

While important developments have been made in tools related to the design and characterisation of pragmatic trials, there remains a lack of information regarding how pragmatism may contribute as a source of heterogeneity among studies using similar or the same interventions. Although the evaluation of pragmatic and explanatory primary trials in systematic reviews is an emerging topic, researchers have focused mainly on the application and reliability measures of PRECIS-2, PRECIS and its derivatives. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression are ways to explore heterogeneity and gain insight into why results from outcomes may be inconsistent between studies.12 If heterogeneity is substantial, due to the degree of pragmatism, it might not be appropriate to pool data from pragmatic and explanatory trials. The use of the PRECIS-2 tool could provide important information for authors of systematic reviews with regards to pooling data from primary RCTs based on the degree of pragmatism.

Objectives

The primary objective of this research is to investigate the role of pragmatism as a source of heterogeneity in systematic reviews. This will be accomplished by (1) identifying systematic reviews with meta-analyses of RCTs with moderate to high heterogeneity (I2 ≥50%), (2) applying the PRECIS-2 scoring system to RCTs of systematic reviews to assess the contribution of pragmatism, (3) evaluating inter-rater reliability of PRECIS-2, (4) determining how much of this heterogeneity may be explained by pragmatism.

Methods

Study design

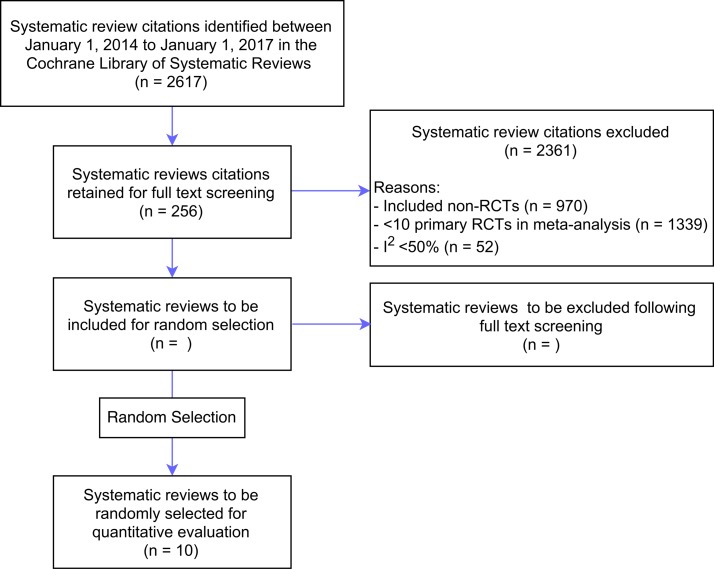

This study will be designed as a cross-sectional methodological review. A literature search using the Cochrane Library will be conducted for published reviews of RCTs from 1 January 2014 to 1 January 2017. This database was selected based on the consistency of methodology and the quality of the systematic reviews.13 The search was limited to the Cochrane Reviews Database which included the key terms randomize and RCT* in titles, abstracts and keywords with word variations in an effort to capture all systematic reviews of RCTs published during the selected time frame. Inclusion criteria will include systematic reviews of RCTs from any Cochrane Review Group with at least 10 studies considered in one pooled effect relating to the primary outcome and moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I2 ≥50%).12 Exclusion criteria will include systematic reviews of non-randomised, quasi-randomised or crossover trials. Two reviewers (TA, KA) will independently screen titles and abstracts retrieved by the search. Full texts of the systematic reviews will be evaluated for study eligibility criteria. Disagreements about review inclusion will be resolved by consensus or expert advice (LM) if a consensus cannot be reached. Of the eligible systematic reviews, 10 will be selected at random to keep the data manageable. Random selection will be performed using a random numbers generator in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V.23 (IBM Corp). A summary of the planned systematic review selection procedure is outlined in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the systematic review selection procedure. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Data abstraction

Three reviewers (TA, KA, DL) will use standardised data abstraction forms to extract data independently from included trials, in duplicate. Disagreements between the reviewers will be resolved by adjudication from the uninvolved reviewer or by expert opinion (LM). In the event of missing or unclear information, authors of the systematic review will be contacted for clarification. Title and abstract screening, full text screening and data abstraction will be performed in Distiller SR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). Extracted data will include information such as bibliographic details (author, year of publication), study population characteristics, primary outcome, intervention details, risk of bias assessment, pooled measures of effect, heterogeneity and any reported or tested explanations of heterogeneity.

The PRECIS-2 tool will be applied to all primary studies within their respective systematic reviews. Studies will be scored across each of the nine PRECIS-2 domains and a summary score will be provided for each study ranging from 9 (very explanatory) to 45 (very pragmatic). A calibration phase with all reviewers will take place using a minimum of 10 primary RCTs to ensure consistency in scoring across each PRECIS-2 domain. Following calibration, evaluation of the PRECIS-2 domains for the remainder of the included primary RCTs will be performed independently, in duplicate. The ICC will be used to measure inter-rater reliability between independent raters on PRECIS domains and the summary score. An ICC of 0.21–0.40 will be considered fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 will be considered moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 will be considered substantial agreement and 0.81–1.0 will be considered almost perfect agreement.14 Scoring disagreements will be resolved by consensus or additional scoring from the uninvolved reviewer if needed.

Data analysis

General characteristics of included systematic reviews will be described by intervention, number of primary RCTs, number of participants, mean duration of primary RCTs and primary outcome. These characteristics will be reported either descriptively using mean/median (SD/quartiles) or by frequency (per cent) as appropriate. The results of included systematic reviews will be described using the pooled measure of effect, heterogeneity of the primary outcome (I2) and risk of bias assessment for each primary RCT. The PRECIS-2 scores for primary RCTs will be described for each domain and for the summary score (9–45). The PRECIS-2 ‘wheel’ will be used to visually depict how explanatory or pragmatic a primary RCT is based on scores from each of the nine domains.

Several statistical approaches will be undertaken to explore pragmatism as a potential source of heterogeneity. As a primary analysis, linear random effects meta-regression models will be built for each systematic review. The RCT will be the unit of analysis, the outcome variable for each study will be the mean difference or log OR depending on the nature of the outcome, accompanied by the SE. The main predictors will be the degree of pragmatism as a continuous variable through the PRECIS-2 summary score, individual PRECIS-2 domains and risk of bias. Beta-coefficients will be interpreted to indicate how much a unit change in pragmatism would lead to changes in the outcome, and will be presented with 95% CIs and p values. The level of significance will be set at α=0.05. Model fit will be assessed using R.2 As a secondary analysis, the interaction between risk of bias and PRECIS-2 score will be explored within systematic reviews. These analyses will be repeated across systematic reviews, by pooling systematic reviews with similar outcome types (binary, continuous or time-to-event).

As there are no specific cut-off values for what is considered a pragmatic or explanatory trial, RCTs will be classified in three categories, similar to Yoong et al.8 The PRECIS-2 summary score will be divided into tertiles to represent RCTs that are predominantly explanatory, combined explanatory/pragmatic and predominately pragmatic. As a secondary analysis, these classifications will be used to explore the contribution of pragmatism on heterogeneity among RCTs in a systematic review.

Data from primary studies will be analysed using Stata/IC 15.0 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA) andReview Manager (RevMan) 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Meta-regression will be performed using Stata/IC 15.0 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Discussion and dissemination

Although the concept of pragmatism was first described in 1967, the design and conduct of pragmatic trials have recently gained momentum as healthcare providers and decision-makers seek to determine whether available evidence may be translated and used in real-world practice.15 Thus, the evaluation of pragmatism in primary RCTs of systematic reviews is a novel and relevant topic. While the PRECIS-2 tool is intended for researchers to align their RCT design to a context in which they believe the intervention would be useful and RCT results applicable; it is decision-makers who will evaluate the RCT and make decisions regarding the implementation of the tested intervention.16 Systematic reviews of RCTs are an essential scientific activity and the evidence upon which clinical and health system decisions are made.17 With this in mind, it is important to consider the degree of pragmatism as a source of heterogeneity in systematic reviews as unexplained heterogeneity can lead to downgrading the body of evidence which in turn could affect whether or not the tested intervention is implemented in a healthcare system.18 Additionally, if moderate to substantial heterogeneity cannot be explained, it may not be appropriate to meta-analyse outcome data from pragmatic and explanatory trials despite their congruent interventions and outcomes.

One limitation is that there may be individual-level factors that could explain heterogeneity; however, they have not been explored by authors of the Cochrane review or not included in this review. A second limitation of the research is that only Cochrane systematic reviews will be considered and they represent only a portion of a systematic reviews. It is possible that there are reviews of important interventions that will not be considered in this research. For the purposes of this methodological review, Cochrane reviews were regarded as ideal since they have consistent methodology, reporting standards and are widely accepted as the gold standard of systematic reviews.19

In summary, this research project will be one of the first to evaluate the PRECIS-2 tool in a systematic review setting. The results from this research will provide further inter-rater reliability information for PRECIS-2, guidance for methods on how to treat and analyse pragmatic and explanatory trials in systematic reviews, and highlight important subgroup considerations for future systematic reviews.

Ethics committee approval was not required for this research as it uses previously published data. On completion, this evaluation of the literature will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication. Research results may also be presented at applicable scientific conferences.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TA, LM, RN and JB contributed to the conception and design; TA and LM wrote the first draft of the protocol; LM, KSA and DL contributed to critical revision of the protocol and all authors approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:464–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, et al. Clinical epidemiology: how to do clinical practice research LWW medical book collection. 3rd ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:496 xv. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis 1967;20:637–48. 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, et al. A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1040–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tosh G, Soares-Weiser K, Adams CE. Pragmatic vs explanatory trials: the pragmascope tool to help measure differences in protocols of mental health randomized controlled trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koppenaal T, Linmans J, Knottnerus JA, et al. Pragmatic vs. explanatory: an adaptation of the PRECIS tool helps to judge the applicability of systematic reviews for daily practice. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1095–101. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoong SL, Wolfenden L, Clinton-McHarg T, et al. Exploring the pragmatic and explanatory study design on outcomes of systematic reviews of public health interventions: a case study on obesity prevention trials. J Public Health 2014;36:170–6. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD001871. 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Witt CM, Manheimer E, Hammerschlag R, et al. How well do randomized trials inform decision making: systematic review using comparative effectiveness research measures on acupuncture for back pain. PLoS One 2012;7:e32399 10.1371/journal.pone.0032399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loudon K, Zwarenstein M, Sullivan FM, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool has good interrater reliability and modest discriminant validity. J Clin Epidemiol 2017 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petticrew M, Wilson P, Wright K, et al. Quality of cochrane reviews. quality of cochrane reviews is better than that of non-cochrane reviews. BMJ 2002;324:545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patsopoulos NA. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Loudon K. PRECIS-2 helps researchers design more applicable RCTs while CONSORT Extension for Pragmatic Trials helps knowledge users decide whether to apply them. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;84:27–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulrow CD. Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;309:597–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence--inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1294–302. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith R. The Cochrane collaboration at 20. BMJ 2013;347:f7383. 10.1136/bmj.f7383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.