Abstract

Objective

At the end of 2012, the Indonesian government enacted tobacco control regulation (PP 109/2012) that included stricter tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) controls. The PP did not ban all forms of TAPS and generated a great deal of media interest from both supporters and detractors. This study aims to analyse stakeholder arguments regarding the adoption and implementation of the regulation as presented through news media converge.

Design

Content analysis of 213 news articles reporting on TAPS and the PP that were available from the Factiva database and the Google News search engine.

Setting

Indonesia, 24 December 2012–29 February 2016.

Methods

Arguments presented in the news article about the adoption and implementation of the PP were coded into 10 supportive and 9 opposed categories. The news actors presenting the arguments were also recorded. Kappa statistic were calculated for intercoder reliability.

Results

Of the 213 relevant news articles, 202 included stakeholder arguments, with a total of 436 arguments coded across the articles. More than two-thirds, 69% (301) of arguments were in support of the regulation, and of those, 32.6% (98) agreed that the implementation should be enhanced. Of 135 opposed arguments, the three most common were the potential decrease in government revenue at 26.7% (36), disadvantage to the tobacco industry at 18.5% (25) and concern for tobacco farmers and workers welfare at 11.1% (15). The majority of the in support arguments were made by national government, tobacco control advocates and journalists, while the tobacco industry made most opposing arguments.

Conclusions

Analysing the arguments and news actors provides a mapping of support and opposition to an essential tobacco control policy instrument. Advocates, especially in a fragmented and expansive geographic area like Indonesia, can use these findings to enhance local tobacco control efforts.

Keywords: tobacco control, news analysis, taps, regulation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is among the first that systematically analyses tobacco control arguments presented in news articles in a low-income setting.

This study provide insight on policy and advocacy action that could be taken in decentralised setting.

A limitation of this study is that it may not fully represent all the news generated about the Indonesian tobacco advertising laws during the time periods, however, this was negated including results from multiple databases.

Introduction

Limited control of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) in Indonesia has allowed the tobacco industry to remain free to advertise their products via both mainstream and new media.1 2 The ubiquitous presence of tobacco promotion and marketing has been described as a ‘step back in time’3 and signifies how Indonesia is lagging behind other nations in reducing tobacco use. To add to this picture, the rising use of the internet, including social media, for tobacco promotion2 4–7 has resulted in inescapable exposure to TAPS.

Exposure to tobacco advertisements contributes to smoking uptake.8–11 This is also true for online promotions, with youth exposed to tobacco branding through the internet being more susceptible to smoking.12 High exposure to TAPS coupled with easy access to cigarettes has resulted in high tobacco prevalence among both Indonesian adults and youth. The number of adult smokers is the highest in South East Asia, with the 61.4 million smokers accounting for half of the total adult smoker population in the region.13 14 Two-thirds of the adult male population smoke,13 15 and one-third of boys age 13–15 years are also smokers.16 The prevalence of smoking among children aged 10–14 years increased from 9% in 1995 to 17.4% in 2010, resulting in an additional 4 million children smoking per year.14 In addition, smoking prevalence among girls age 13–15 years was tripled between 2007 and 2014, from 0.9%17 to 3.4%.18 Increasing smoking prevalence among young people will escalate the future social and economic burden of chronic disease.19 This could be readily prevented by adopting effective tobacco control policies, including a comprehensive TAPS ban.19–21

In 2012, the Ministry of Health (MoH), supported by growing tobacco control advocacy from civil society and academics was able to succeed in enacting regulation PP 109/2012 (PP),22 which includes a number of evidence-based tobacco control policies found in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).23 The PP places stricter controls on TAPS compared with previous regulations. It includes limitations on: sponsorship of sport, music and community events, print and broadcast media promotion and the size and placement of billboards. Broadcast of tobacco commercials on television is permitted between 21:00 and 5:00. The regulation also requires a 40% pictorial health warning on cigarette packs and prohibits the sale of cigarettes to people under 18 years old.24 However, the regulation has not fully met the expectations of tobacco control advocates since it only partially bans TAPS.22 Unsurprisingly, the tobacco industry lobby has also raised concerns about the regulation. The tobacco industry has a long history of influential relationships with Indonesian politicians and economists, primarily due to the perceived positive contribution it makes to both national and subnational government revenue and employment.25

Understanding these stakeholder standpoints as presented through the news media, both in support and opposed to the policy changes, is useful in optimising the adoption and implementation of the regulation.26 Analysis of news both in print and online has enhanced tobacco control policy implementation and has provided constructive feedback for tobacco control advocacy efforts.27–29 Identifying the opposing arguments and commentary presented on policy reform assists tobacco control advocates in preparing counter arguments.30 31 Effective media engagement is essential to the continued adoption of progressive tobacco control regulations in Indonesia. Maintaining effective, positive and continuous coverage will ensure the health priorities of tobacco control remain part of public discussion and on policy-makers’ radar.32

To date, analysis of tobacco control news media coverage in Indonesia is limited. Media monitoring conducted by the Tobacco Control Support Centre Ikatan Ahli Kesehatan Masyarakat Indonesia shows that more pro-tobacco control news is generated33; however, further content analysis has not been conducted. Our study analyses the stakeholder arguments presented through the print and online news media in support and against the adoption and implementation of tobacco control regulations intended to limit TAPS.

Method

Dataset

The dataset comprised of Indonesia news items (articles) available from Factiva (https://global-factiva-com) for print and online sources and Google News (https://news.google.com.au/) for additional online news media that focused on the tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship regulation (PP 109/2012). Factiva indexes a wide range of newspapers, newswires and other type of publications from over 36 000 sources, while Google News aggregates headlines from news sources worldwide.

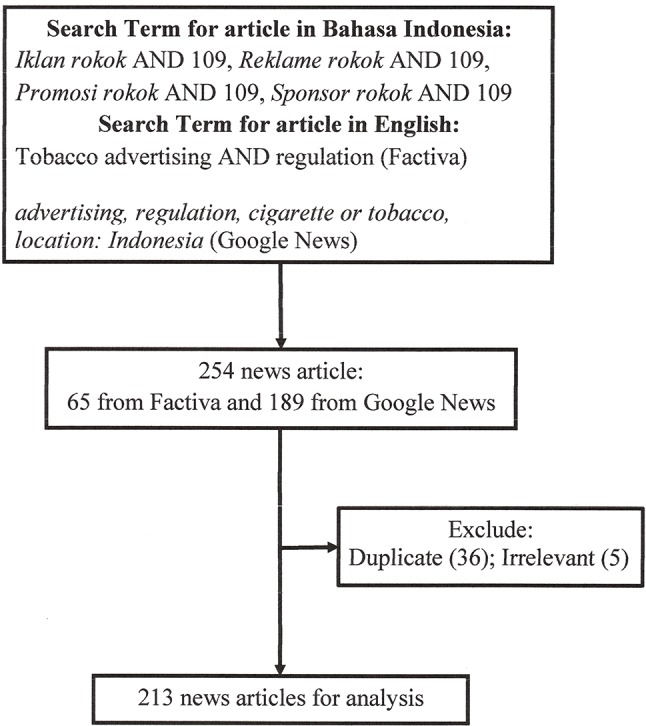

We included articles in English and Bahasa Indonesia. For articles in Bahasa Indonesia, we used the Indonesian words for advertisement, promotion and sponsorship, which are: iklan/reklame, promosi and sponsor, respectively; and instead of using tobacco, the more appropriate term, cigarette, which is rokok, was applied. This was combined with 109, for the number of the tobacco control regulation PP 109/2012. For articles in English from Factiva, the term tobacco advertising was combined with regulation. While those from Google news; after testing multiple searches, we achieved the most relevant results by using the search terms: advertising, regulation, cigarette or tobacco, location: Indonesia (Figure 1). Google news results were expanded to include any related articles. The time period was set up from 24 December 2012, following the signing of the regulation (PP) on that date through 29 February 2016, the date of our data collection. Duplicate articles and articles that did not include any discussion of TAPS and tobacco control regulation were excluded.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

Data management and coding procedure

Articles that met the inclusion criteria were entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2013). Information recorded included: date of publication, source (print/online), name of newspaper/online media site, title and the name(s) of the person(s)/organisation(s) that presented any arguments found in the articles.

The first step of the coding procedure was a preliminary exploration of 25 news articles to develop categories for coding the arguments. The arguments were categorised as in support of the regulation if the arguments included supported either the regulation or enhanced tobacco control measures. Opposed arguments were those that suggested watering down the regulation, hampering/delaying the implementation of the regulation and took a negative view towards tobacco control efforts. In total, 13 categories emerged: 10 in support and 3 opposed and clear definitions were applied to each category to ensure consistent coding. Then, the remaining articles were analysed and the categories were refined down to nine in support categories and expanded to eight opposed to the regulation. If the argument did not belong to any of these categories, it was assigned to an additional category ‘other arguments’. The ‘other arguments’ category was included twice, once for the in support and once for the opposed side to give a final total of 19 categories (table 1). Each news article was then read closely and every argument presented in the article was separately categorised.

Table 1.

Definition of the arguments and an illustrative example

| Arguments | Definition | Example of the argument |

| In support categories | ||

| Enhance the implementation | Need to improve the implementation of the regulation including better enforcement | …the Indonesian government needed to step up its efforts… |

| Scale up the regulation | Need to enhance coverage/scope or comprehensiveness of the regulation and the need for other measures | The regulation is weak and provide freedom to industry to promote and sponsored…* |

| Protect young people | Prevent tobacco harm and smoking initiation among young people | …to restrict the airing…of tobacco product advertisements, saying that the ads could be exposing the country's young to smoking habits |

| Protect people’s health | Protect people/public health, includes protecting non-smoker/passive smoker | …but the government is firm that we have to protect the health of the people |

| Reduce smoking demand | Reduce smoking addiction, support smoking cessation, reduce number of smokers | We really want to see people stop smoking for their best, not ours… |

| Prevent new smoker | Prevent initiation of smoking; do not specifically mentioning youth | …to prevent 3 million new smokers in 2013* |

| Financial/social impact | Preventing financial and social impact of tobacco-related disease | …to tackle health and economic costs associated with smoking |

| Education | Contribute to improve awareness on tobacco harm | PP 109/2012…aiming that people will be encourage to know danger of smoking…* |

| Comments on tobacco industry strategies | Comments on tobacco industry strategies to thwart the implementation and enforcement of the regulation, and tobacco control efforts | …Powerful cigarette companies are still trying to skirt tighter regulation and work around existing restrictions… |

| Other pros | Positive argument that are not fit in any of in support categories | Musicians should be professional… without sponsors* |

| Opposed categories | ||

| Reduce government income | Reduce government income/revenue | Advertisement tax revenue target for this year lower than previous year…This is because of government regulation no 109/2012…* |

| Disadvantage on TI | Negative impact on tobacco industry productivity/income | It will have impact on small and medium-scale industry* |

| Concern on tobacco farmer/tobacco industry workers welfare | Negative impact on social and financial well-being of tobacco farmer/tobacco industry workers | …termination of employment due to many pressure…including PP 109/2012* |

| Vested/foreign interest | Foreign interest drive the regulation and other tobacco control measures | …big influence of foreign donor for all antitobacco campaign…* |

| By-law violate national law | Subnational regulation (by-law) could not be more comprehensive or stricter than national regulation | This regulation (governor regulation No 1/2015) violate…PP Nomor 109/2012 (national regulation)* |

| Music and sport productivity | Negative impact on music/sport productivity | …Cause the sport will die* |

| Kretek is a heritage and cigarette is legal | Argument that cigarette is a legal product and non- addictive and kretek (mixed of tobacco and cloves) is a national heritage/product | …Eradicating kretek means we will lose our national character |

| Disadvantage other businesses | Negative impact on other business such as advertising, television, printing company | …it will reduce advertising company income…* |

| Other cons | Negative arguments that are not fit in any opposed categories | PP 109/2012…should be enough since it is very strict. There is no need for additional regulation by ratifying FCTC* |

* The arguments were translated from Bahasa Indonesia.

FCTC, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; TI, tobacco industry.

The individuals and/or organisations news actors included in the articles were categorised as: (1) national government, if the actors were from the national government level including the MoH, parliament and/or other national organisation; (2) subnational government, for government, legislator or other official at the province or district level; (3) tobacco control advocates, including civil society, health professionals and academics; (4) tobacco industry/pro-tobacco industry (TI) including cigarette manufacturers and tobacco industry associations; (5) journalist, if no specified individual/organisation made the comments in the articles and (6) others, if they cannot be categorised into the previous groups.

Coding reliability was conducted by seven coders who each coded 20 randomly selected news articles. A Kappa statistic which is a common measure of interobserver agreement was then calculated.34

Descriptive statistics were applied to determine the frequency of the arguments and the news actors. Arguments in Bahasa Indonesia have been translated in to English for this paper and are indicated with * symbols in quoted material.

Results

A total 254 news items were found, 36 duplicates were excluded and an additional 5 articles were excluded as they did not contain TAPS content. In total, 213 news items, 55 from Factiva and 158 from Google News were included in the final analysis. Out of 213 news items, there were 11 news items that did not contain any arguments, these articles were either describing the content of the regulation, or the preparation process for implementation and enforcement activities. Two hundred and two articles included arguments in support or against the regulation.

A total 436 arguments were found across the 202 articles, 301 (69%) of the arguments were in support of the regulation (table 2). The Kappa statistic for intercoder reliability was 0.7542. A Kappa value above 0.61–0.8 signifies substantial reliability.34

Table 2.

Stakeholders’ arguments towards the PP

| Arguments | National government | Subnational government | TC advocate | TI/Pro TI | Journalist | Other | Total |

| In support | 70 (80.5) | 22 (44.0) | 138 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 60 (87.0) | 11 (39.3) | 301 (69.0) |

| Opposed | 17 (19.5) | 28 (56.0) | 0 (0.00) | 64 (100.0) | 9 (13.0) | 17 (60.7) | 135 (31.0) |

| Total | 87 (100) | 50 (100) | 138(100) | 64(100) | 69(100) | 28(100) | 436 (100) |

TC, tobacco control; TI, tobacco industry.

Almost a third of the arguments were presented by tobacco control advocates, accounting for 138 of the 436 arguments (31.7%), followed by national government, at 87/436 (20.0%). The Ministry of Health made 59 out of the 70 in support arguments attributed to national government stakeholders. National government, tobacco control advocates and journalists, made more positive comments about the regulation at 80.5%, 100% and 87%, respectively, while the tobacco industry and other group made mostly opposing arguments and subnational government arguments were almost evenly split between in support and opposed (table 2).

Arguments in support of the regulation

Arguments in support of the regulation (PP) comprised of 10 categories: including enhancing the implementation, scaling up the regulation, protecting young people, concern for people’s health, reducing demand, preventing new smokers, financial/social impacts, educating people, commenting on tobacco industry strategies and other (table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of arguments to the regulation

| Arguments in support | f | % | Arguments opposed | f | % |

| Enhance the implementation | 98 | 32.6 | Reduce government income | 36 | 26.7 |

| Scale up the regulation | 44 | 14.6 | Disadvantage TI | 25 | 18.5 |

| Protect young people | 29 | 9.6 | Concern on Tobacco farmer/TI workers welfare | 16 | 11.9 |

| Protect people’s health | 23 | 7.6 | Vested/foreign interest | 10 | 7.4 |

| Reduce smoking demand | 16 | 5.3 | By-law violate national law | 9 | 6.7 |

| Prevent new smoker | 9 | 3.0 | Music and sport productivity | 9 | 6.7 |

| Financial/social impact | 7 | 2.3 | Kretek is a heritage and cigarette is legal | 8 | 5.9 |

| Education | 18 | 6.0 | Disadvantage other business | 6 | 4.4 |

| Comment on TI strategy | 49 | 16.3 | Others | 16 | 11.9 |

| Others | 8 | 2.7 | |||

| Total | 301 | 100 | Total | 135 | 100 |

f, frequency; TI, tobacco industry;.

A third—32.6% (98/301)—arguments suggested there was a need to enhance the implementation and enforcement of the regulation, while 14.6% (44/301) arguments stated that the regulation itself needed to be improved to be more comprehensive or that other measures should also be taken (table 3).

In regard to the scaling up the legislation, some highlighted the ineffectiveness of a partial ban and pointed out loopholes in the regulation. Claims were also made that tobacco industry has interfered in the regulation drafting process.

Government Regulation (PP) No.109/2012 on tobacco control, which still allows cigarette advertisements, promotions and sponsorship via all types of media in Indonesia, has made children targets of exploitation for cigarette companies' marketing activities. (TC advocates)35

…he said, the article on the PP is prone to misinterpretation, someone may argue that the video LCD billboard (videotron) is not a broadcasting media. (Subnational government)36*

The enactment of PP No 109/2012 was a compromise between government and the tobacco industry and tobacco control. (Journalist)37*

In terms of the enhancing implementation and enforcement of the regulation, arguments presented suggested that weak and delayed enforcement of regulations is commonplace in Indonesia. The need to improve and enhance actions to increase any chance of a positive impact was stressed.

…as is the case with many other regulations issued throughout the country, it is merely a paper tiger.(Journalist)38

…the Indonesian government needed to step up its efforts if it really wanted to enact any real change and combat the country’s extremely persuasive tobacco industry. (Journalist)39

Health and education concerns were the next most common arguments in support of the regulation, which included 9.6% (29/301) concerned with protecting young people from exposure to cigarette advertising, 7.6% (23/301) with protecting the health of the community, including non-smokers, 5.3% (16/301) with reducing smoking demand include curbing the addiction and smoking cessation and 6.0% (18/301) arguments on improving awareness of tobacco harms.

The minister said that the regulations were aimed at protecting non-smokers and to prevent new smokers, especially young people. (National government)40

In addition, 16.3% (49/301) of the arguments were negative remarks on tobacco industry strategies to derail the regulation. These arguments, asserted that tobacco industry are thwarting the implementation of regulation, interfering in the parliament and implementing marketing strategies that skirt the regulations.

…Powerful cigarette companies are still trying to skirt tighter regulation and work around existing restrictions to promote their deadly products. (Journalist)39

Included in the ‘other in support’ category, were arguments from artists stating that their creativity will not be hampered by the ban of cigarette sponsorship.

…Slank (band) will remain productive without cigarette sponsorship. ‘Musicians should be professional and will continue to strive for success without sponsors. (Other)* 41

Arguments opposed to the regulation

There were nine categories for the 135 arguments not in support of the regulation (table 3). The most common opposed argument at 26.7% (36/135) was about the potential decrease in government revenue from reduced cigarette advertising and tax revenue. This was followed by arguments that the regulation will disadvantage the tobacco industry at 18.5% (25/135), and tobacco farmers and industry workers at 11.1% (15/135).

The cigarette industry will experience significant losses since all productive methods of promotions are being shut down… simultaneously, this will systematically decrease the market. (TI/Pro TI)*42

The Association of Indonesian Tobacco Farmers (APTI) said that in 2013, some 2.1 million tobacco farmers' livelihoods depended on the tobacco industry. (National government)*43

Arguments regarding preserving national pride were accounted for 5.9% (8/135), in contrast to those stating that adopting tobacco control regulations was kowtowing to foreign vested interests at 7.4% (10/135). Kretek (a clove-infused cigarette) was claimed as a national heritage item, which should be preserved. It was argued that interference from foreign countries had driven tobacco control regulation and agendas.

It seems kretek are being criminalised. We should remember that this is a legal product. Eradicating kretek means we will lose our national character. (TI/Pro TI)*43

He stated that foreign interests are trying to kill local industry through a number of regulations. (TI/Pro TI)44*

An additional argument against the regulation, at 6.7% (9/135) was regarding the perceived hierarchy between subnational and national regulation, where it was argued that a by-law should not ‘violate’ national regulation. For instance, stricter by-law in Jakarta and Bogor was viewed as a challenge to the national PP regulation.

Despite several artists stating a positive attitude towards the regulation, 6.7% (9/135) of the opposed arguments suggested that a cigarette sponsorship ban would be harmful to music and sporting events.

If cigarette sponsorship for sports is banned, please provide the substitution. Cause the sport will die,’ he said. (Other)45*

Another argument opposing the regulation 4.4% (6/135) was the supposed negative impact of a cigarette advertising ban would have on other businesses such as television, advertising and print companies.

For the other opposed category, some also suggested that before any enforcement action of the national law could be taken, a by-law also needed be in place. While, the tobacco industry also stated their preference that the PP regulation be adopted over the far stricter WHO FCTC and that stricter regulation will make the illegal cigarette trade flourish.

I think the PP is fair enough, we do not need to ratify FCTC. (TI/Pro TI)* 46

Discussion

Arguments surrounding PP 109/2012 include supporters demanding the PP be tightened with health and education as the primary rationale, while opponents are appealing to loosen or delay its implementation with economic, legal and ideological arguments cited as justification. Effective tobacco control is presented as two opposing frames of either an economic disaster versus an essential health measure. Tobacco control stakeholders must go beyond providing evidence that tobacco advertising laws work to reduce smoking rates and also ensure that the false economic arguments are effectively countered.

More than two-thirds of the arguments were in support of the regulation, signifying an overall positive framing of tobacco advertising regulation in the Indonesian media. This suggests that media engagement on tobacco issues and advocacy activities on both national and subnational levels has been improving.25 Tobacco control advocates should optimise this positive change by continuing to ensure the issues are discussed in the public domain. Enduring media advocacy is proven to increase legislative success, as seen in the case of Australia’s adoption of smoke free bars.30 Coordinated media outreach, press releases and media notification of research findings are all proven strategies.47–50 Social media platforms should also be more systematically embraced due to their increasing popularity and promising evidence on their potency for public health communication and advocacy.51 52

The most common in support argument was that regulation was incomplete and needed to be scaled up to a total ban on TAPS. Partial bans on TAPS enable the tobacco industry to exploit loopholes, circumvent regulations53–55 and shift its marketing to less regulated channels such as event sponsorship and internet-based marketing.4 5 7 56 It is notable that the tobacco industry reluctantly agreed that they would rather bound by the ‘partial’ PP regulation than the stricter WHO FCTC. The industry further argued that WHO FCTC type regulations would increase illicit cigarettes, ignoring the fact that Indonesian cigarettes are among the cheapest in the world.57

Although arguments opposed to the regulation were reported less in the media, the news actors were not simply the expected tobacco industry groups but also government officials, parliamentarians, artists and academics. This reflects the ambiguous nature of the official Indonesian government position towards tobacco control. On one hand, the Ministry of Health released ‘Tobacco Control Roadmap’ while on the other, the Ministry of Industry issued the competing ‘Tobacco Industry Roadmap’. This equivocal standpoint is most clearly reflected by the fact that Indonesia has yet ratify the WHO FCTC—the only country in the Asia Pacific not to do so. The intertwining of politics and tobacco industry profits is apparent, with very high tobacco industry interference in both parliament and government departments.58

Losing government income was most common oppositional argument. This frame of economic loss has been consistently used by the tobacco industry to impede attempts for stronger tobacco control.30 Concerns by provincial and district/city governments that they will lose tax revenue from outdoor tobacco ads is a potential barrier to the successful implementation of PP 109/2012 as they are primarily responsible for policing and enforcing TAPS measures. However, a study in three Indonesian cities revealed that the revenue from cigarette advertisements accounted for no more than 1% of government revenue.59 Since 2014, all subnational governments also receive a share of tobacco excise tax with the amount proportionately distributed based on the population. Fifty per cent of this budget is supposed to be earmarked for public health services and enforcement.60 61 Advocates should focus their arguments to subnational government around easing economic concerns, which may also serve to a boost subnational tobacco control programme.

Other economic arguments such as unemployment and tobacco farmer and worker welfare have been the bulletproof armour of tobacco industry. In truth, employment in the tobacco industry in Indonesia accounts for a relatively small amount of agricultural full-time employment at 1.2% and only 0.53% of total full-time employment. Contribution to manufacturing employment has been declining significantly from 28% in 1970 to less than 6% in 2008, largely due to mechanisation of cigarette manufacturing.57 This doesn’t stop the industry from claiming that this employment restructuring happens because of pressures from government regulation.62 Ensuring these economic realities are communicated to policy-makers and through the media is essential to counter industry economic mythmaking.

In terms of practicality, implementation of TAPS controls within the PP, with the exception of broadcasting regulations, is largely a subnational government responsibility. Implementation of TAPS control by subnational government using the national PP as the legal basis is the most likely path forward but this approach might be tenuous. Implementation and enforcement may viewed as ‘no one’s job’ because the subnational government bill number 23/2014 states that the civil police are only responsible for enforcing non-criminal by-law.63 Some have argued then, that a by-law must be in place before the PP could be enforced, which adds significant delays and another possible obstacle to full implementation. This supposed hierarchy of regulation was then used by tobacco industry lobbyists to obstruct subnational government implementation efforts. They threatened that a by-law could not impose stronger regulations than PP; for example Jakarta and the City of Bogor adopted a total ban on outdoor advertisements while the PP only prescribes a partial ban.64 65 However, PP article 34 clearly states that extensions to the national regulation should in fact be made on the by-law,24 suggesting that the tobacco industry claims are intentionally misleading in an attempt to discourage other subnational governments from adopting progressive laws. Adopting a by-law is a double-edge sword, it is an opportunity to adopt a stronger ban but also provides a window for yet further delaying implementation. The tobacco industry has exploited this opportunity for its own gain, and tobacco control advocates equally need to find a strategic way to take advantage of this possibility for greater reforms. Developing key recommendation for directly enforcing the PP while also developing a stronger by-law must be a priority.

Other common arguments against the regulation featured ideological and nationalist framing, Kretek was viewed as a national heritage item versus tobacco control being driven by foreign interests. Kretek is considered an indigenous product to Indonesia and has long been used as an argument to preserve smoking and to protect the industry.66 There are several organisations that label themselves as ‘Kretek saviours’. Kretek may be formally recognised as an item of ‘national heritage’ if a currently draft tobacco control bill is successfully adopted by the Indonesian legislature. This bill may become a significant roadblock to TAPS control efforts since it weakens most of the PP articles that relate to TAPS. Tobacco control advocates should explore appropriate counter arguments through increased understanding of the social context of smoking and testing messages that emphasise that mass-produced, deadly products are not part of a healthy, vibrant ‘culture’.

Further to this, the tobacco industry accuses tobacco control research and regulation activities as being driven by foreign interest. This ignores the fact that tobacco company shares in Indonesia today belong primarily to multinational/transnational companies.67 With regards to foreign influence, the Indonesian health sector receives funding not only for tobacco control activities but also for many other health priorities such as tuberculosis, malaria and HIV and AIDS treatment and prevention.68 Moreover, for the purpose of introducing and implementing appropriate tobacco control policy, support for strengthening local capacity is considered essential by foreign funding bodies.69 70 Preparing case studies that showcase promising local evidence of effective tobacco control programme and polices is essential.

This is one of the first studies to systematically analyse content of the news reporting on tobacco advertising laws in Indonesia. One limitation of the study is that it may not fully represent all the news generated about TAPS and PP 109/2012 during the time periods, as we must rely on what was made available on Factiva. However, we tried to negate this by including the additional Google News search. Understanding the arguments reported by news media will assist advocates in building effective counter-arguments and aid in advancing legislative reform.31 Making media analysis available to advocates, especially in a fragmented and expansive geographic area, like Indonesia, will ensure lessons learned are shared in a timely manner. Incorporating practical tips and advice about media messaging form others experience is especially important in settings where much of the advocacy and policy reform is ongoing and at subnational level. Indonesia’s decentralised governance systems and regulation hierarchy could become either enablers or barriers to a total TAPS ban. In addition to developing a strong national regulation or pushing eventual WHO FCTC accession, finding ways to optimise this opportunity and to minimise the time lag for developing a by-law should be fully explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all coders for assistance with intercoder reliability test.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drayuswandewi

Contributors: PASA was involved in design and conception of the study, gathering and analysing the data, drafting and editing the manuscript. BF was involved in design and conception of the study, drafting and editing the manuscript and providing qualitative expertise.

Funding: PASA received scholarship from Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) for her PhD.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Reference

- 1. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. The tobacco source book: data to support a National Tobacco Control Strategy (English translation). Jakarta: Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosemary R. A content analysis of tobacco advertising and promotion for Indonesian tobacco brands on YouTube [Master Student Thesis: The University of Sydney, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCall C. Tobacco advertising still rife in southeast Asia. Lancet 2014;384:1335–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61804-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freeman B, Chapman S. British American Tobacco on Facebook: undermining Article 13 of the global World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tob Control 2010;19:e1–e9. 10.1136/tc.2009.032847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freeman B, Chapman S. Is ‘YouTube’ telling or selling you something? Tobacco content on the YouTube video-sharing website. Tob Control 2007;16:207–10. 10.1136/tc.2007.020024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang F, Zheng P, Yang D, et al. . Chinese tobacco industry promotional activity on the microblog Weibo. PLoS One 2014;9:e9936:e99336. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Freeman B, Chapman S. Open source marketing: camel cigarette brand marketing in the ‘Web 2.0’ world. Tob Control 2009;18:212–7. 10.1136/tc.2008.027375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ, Sargent JD, et al. . Tobacco promotion and the initiation of tobacco use: assessing the evidence for causality. Pediatrics 2006;117:e1237–e1248. 10.1542/peds.2005-1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Donovan RJ, Jancey J, Jones S. Tobacco point of sale advertising increases positive brand user imagery. Tob Control 2002;11:191–4. 10.1136/tc.11.3.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emory KT, Messer K, Vera L, et al. . Receptivity to cigarette and tobacco control messages and adolescent smoking initiation. Tob Control 2015;24:281–4. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;10:CD003439. 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunlop S, Freeman B, Perez D. Exposure to Internet-Based Tobacco Advertising and Branding: Results From Population Surveys of Australian Youth 2010-2013. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e104. 10.2196/jmir.5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organisation. In: Soewarta Kosen EOR, Taitt B, eds Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Indonesia Report 2011World Health Organisation-SEARO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lian TY, Dorotheo U. The Asean Tobacco Control Atlas : Kin F, Domilyn C, Villareiz C, . 2 ed Thailand: South East Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ministry of Health. Riset Kesehatan Dasar. Jakarta: Ministry of Health Indonesia, 20132013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organisation. Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Indonesia Reports, 2014: World Health Organisation-SEARO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. Global School-based Student Health Survey: Indonesia 2007 Fact Sheet Jakarta: Ministry of Health of Indonesia. 2007. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/noncommunicable_diseases/data/ino_ncd_reports/en/

- 18. World Health Organisation - Regional Office for South-East Asia. Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS): Indonesia report, 2014. New Delhi: WHO-SEARO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, et al. . Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet 2006;367:749–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68192-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chapman S. The denormalisation of smoking. Public health advocacy and tobacco control: making smoking history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2008:153–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chapman S. Vector control: controlling the tobacco industry and its promotions. Public health advocacy and tobacco control: making smoking history. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2008:172–97. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tandilittin H. Civil Society and Tobacco Control in Indonesia: The Last Resort. The Open Ethics Journal 2013;7:11–18. 10.2174/1874761201307010011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organisation. Guideline for implementation of article 13 of World Health Organisation framework convention on tobacco control (Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship: World Health Organisation; http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_13/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 24. Government of Indonesia. Peraturan Pemerintah Republic Indonesia No 109 Tahun 2012 Tentang Pengamanan Bahan Yang Mengandung Zat Adiktif Berupa Produk Tembakau Bagi Kesehatan. Jakarta: Republic of Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Achadi A, Soerojo W, Barber S. The relevance and prospects of advancing tobacco control in Indonesia. Health Policy 2005;72:333–49. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dorfman L. Studying the news on public health: how content analysis supports media advocacy. Am J Health Behav 2003;27(Suppl 3):217–26. 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s3.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, et al. . Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tob Control 2003;12(Suppl II):75ii–81. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He S, Shen Q, Yin X, et al. . Newspaper coverage of tobacco issues: an analysis of print news in Chinese cities, 2008-2011. Tob Control 2014;23:345–52. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Long M, Slater MD, Lysengen L. US news media coverage of tobacco control issues. Tob Control 2006;15:367–72. 10.1136/tc.2005.014456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Champion D, Chapman S. Framing pub smoking bans: an analysis of Australian print news media coverage, March 1996-March 2003. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:679–84. 10.1136/jech.2005.035915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freeman B. Tobacco plain packaging legislation: a content analysis of commentary posted on Australian online news. Tob Control 2011;20:361–6. 10.1136/tc.2011.042986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chapman S. The place of advocacy in tobacco control. Public health advocacy and tobacco control: making smoking history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2008:23–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tobacco Control Support Center. Share of voice media coverage. Presented at tobacco control network meeting. Jakarta: Tobacco Control Support Center (TCSC)-Ikatan Ahli Kesehatan Masyarakat Indonesia (IAKMI), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The Jakarta Post. Anti-tobacco campaign urges youth to avoid smoking Jakarta2014. 2014. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/10/27/anti-tobacco-campaign-urges-youth-avoid-smoking.html

- 36. Cara CC. Konten Videotron di Solo Dinilai Langgar Aturan 2015. 2015. http://www.solopos.com/2015/11/25/664701-664701

- 37. Julianto I. Pro-Kontra Regulasi Rokok di Indonesia 2013. 2013. http://bisniskeuangan.kompas.com/read/2013/02/01/1727590/Pro-Kontra.Regulasi.Rokok.di.Indonesia

- 38. Angelia J. Students join movement against cigarette ads 2015. 2015. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/11/13/students-join-movement-against-cigarette-ads.html

- 39. Harfenist E. The True Smoker: An icon of Indonesia’s refusal to quit lax smoking regulations. 2015. http://jakarta.coconuts.co/2015/10/20/true-smoker-icon-indonesias-refusal-quit-lax-smoking-regulations

- 40. Faizal EB. Cigarette smoking? It's all in your mind, minister says: Factiva. 2013. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/10/16/cigarette-smoking-it-s-all-your-mind-minister-says.html

- 41. Handoko DT. Soal Larangan Sponsor Rokok, Ini Kata Bimbim Slank. 2013. http://m.tempo.co/read/news/2013/06/07/219486324/Soal-Larangan-Sponsor-Rokok-Ini-Kata-Bimbim-Slank

- 42. Arief T. IKLAN ROKOK: Ruang Promosi Dipersempit, Pengusaha Rokok Mengeluh. 2015. http://industri.bisnis.com/read/20150309/12/410019/iklan-rokok-ruang-promosi-dipersempit-pengusaha-rokok-mengeluh

- 43. Perdani Y. The smoking dillema. 2016. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/01/10/the-smoking-dilemma.html

- 44. Asril S. Pengusaha Tuding Asing Ingin Matikan Pabrik Rokok. 2013. http://bisniskeuangan.kompas.com/read/2013/11/28/1004023/pengusaha-tuding-asing-ingin-mematikan-pabrik-rokok

- 45. Sponsor Rokok Dilarang, Even Olahraga Dikhawatirkan Mati. 2013. https://www.bola.net/otomotif/sponsor-rokok-dilarang-even-olahraga-dikhawatirkan-mati-6ff6b9.html

- 46. Purwantono I. Industri Rokok Pilih PP 109/2012 Daripada FCTC. 2014. http://ekonomi.inilah.com/read/detail/2066784/industri-rokok-pilih-pp-1092012-daripada-fctc

- 47. Pederson LL, Nelson DE, Babb S, et al. . News media outreach and newspaper coverage of tobacco control. Health Promot Pract 2012;13:642–7. 10.1177/1524839911424907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chapman S, Dominello A. A strategy for increasing news media coverage of tobacco and health in Australia. Health Promot Int 2001;16:137–43. 10.1093/heapro/16.2.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mackenzie R, Chapman S. Pig's blood in cigarette filters: how a single news release highlighted tobacco industry concealment of cigarette ingredients. Tob Control 2011;20:169–72. 10.1136/tc.2010.039776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stillman FA, Cronin KA, Evans WD, et al. . Can media advocacy influence newspaper coverage of tobacco: measuring the effectiveness of the American stop smoking intervention study's (ASSIST) media advocacy strategies. Tob Control 2001;10:137–44. 10.1136/tc.10.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schein R, Wilson K, Keelan J. Literature review on effectiveness of the use of social media: a report for peel public health: Peel Public Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Freeman B. New media and tobacco control. Tob Control 2012;21:139–44. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Assunta M, Chapman S. "The world's most hostile environment": how the tobacco industry circumvented Singapore's advertising ban. Tob Control 2004;13(suppl_2):ii51–ii57. 10.1136/tc.2004.008359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Assunta M, Chapman S. Industry sponsored youth smoking prevention programme in Malaysia: a case study in duplicity. Tob Control 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii37–ii42. 10.1136/tc.2004.007732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. MacKenzie R, Collin J, Sriwongcharoen K. Thailand--lighting up a dark market: British American tobacco, sports sponsorship and the circumvention of legislation. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:28–33. 10.1136/jech.2005.042432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carter SM. Going below the line: creating transportable brands for Australia's dark market. Tob Control 2003;12(90003):87iii–94. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Barber S, Adioetomo S, Ahsan A, et al. . Tobacco Economics in Indonesia. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Assunta M, Dorotheo EU. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: a tool for measuring implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Tob Control 2016;25:313–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yulianty V, Yudiastuti S, Haksama S, et al. eds Studi Tentang Pendapatan Daerah dari Advertensi Tembakau Di Semarang, Surabaya dan Pontianak, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Government of Indonesia. Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Republik Indonesia Nomor 102/PMK.07/2015 Tentang Perubahan Atas Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 115/PMK.07/2013 Tentang Tata Cara Pemungutan Dan Penyetoran Pajak Rokok Ministry of Finance: Republic of Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Government of Indonesia. Undang Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 28 Tahun 2009 Tentang Pajak Daerah dan Retribusi Daerah, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hakim A. Sampoerna beri pelatihan karyawan terkena dampak restrukturisasi. Antara, 2014. https://global-factiva-com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/

- 63. Government of Indonesia. Undang Undang Republik Indonesia No 23 Tahun 2014 Tentang Pemerintahan Daerah. Jakarta: Republic of Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Setyadi A. Dianggap Lampaui Kewenangan, DPR Kritik Ahok. 2015. updated 29 April 2015 http://news.okezone.com/read/2015/04/28/338/1141595/dianggap-lampaui-kewenangan-dpr-kritik-ahok

- 65. Purnama RR, Tabrak UU. Ahok seperti Kebal Hukum. 2015. updated 11 April 2015 http://metro.sindonews.com/read/988102/171/tabrak-uu-ahok-seperti-kebal-hukum-1428736776

- 66. Nichter M, Padmawati S, Danardono M, et al. . Reading culture from tobacco advertisements in Indonesia. Tob Control 2009;18:98–107. 10.1136/tc.2008.025809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Achadi A, et al. . Roadmap to a tobacco epidemic: transnational tobacco companies invade Indonesia. Tob Control 2012;21:306–12. 10.1136/tc.2010.036814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dugay C. Indonesia’s top 10 donors: Responding to the promise of transformation 2012 [13 August 2012:. https://www.devex.com/news/indonesia-s-top-10-donors-responding-to-the-promise-of-transformation-78905

- 69. Chantornvong S, Collin J, Dodgson R, et al. . Political economy of tobacco control in low-income and middle-income countries: lessons from Thailand and Zimbabwe. Global Analysis Project Team. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:913–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. World Health Organisation. Tobacco free initiative: tobacco control in Indonesia. 2015. www.who.int/tobacco/about/partners/bloomberg/idn/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.