Abstract

Introduction

A common reason for frequent use of healthcare services is the complex healthcare needs of individuals suffering from multiple chronic conditions, especially in combination with mental health comorbidities and/or social vulnerability. Frequent users (FUs) of healthcare services are more at risk for disability, loss of quality of life and mortality. Case management (CM) is a promising intervention to improve care integration for FU and to reduce healthcare costs. This review aims to develop a middle-range theory explaining how CM in primary care improves outcomes among FU with chronic conditions, for what types of FU and in what circumstances.

Methods and analysis

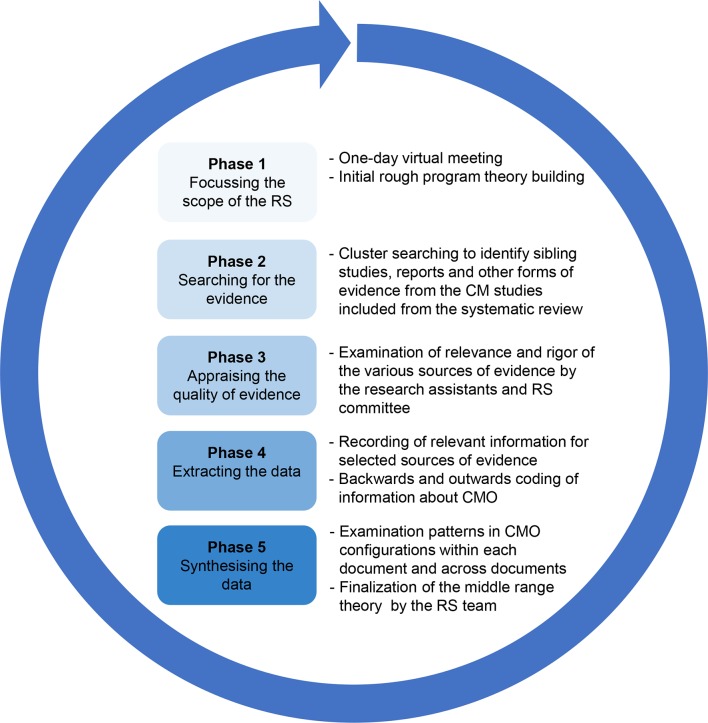

A realist synthesis (RS) will be conducted between March 2017 and March 2018 to explore the causal mechanisms that underlie CM and how contextual factors influence the link between these causal mechanisms and outcomes. According to RS methodology, five steps will be followed: (1) focusing the scope of the RS; (2) searching for the evidence; (3) appraising the quality of evidence; (4) extracting the data; and (5) synthesising the evidence. Patterns in context–mechanism–outcomes (CMOs) configurations will be identified, within and across identified studies. Analysis of CMO configurations will help confirm, refute, modify or add to the components of our initial rough theory and ultimately produce a refined theory explaining how and why CM interventions in primary care works, in which contexts and for which FU with chronic conditions.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics is not required for this review, but publication guidelines on RS will be followed. Based on the review findings, we will develop and disseminate messages tailored to various relevant stakeholder groups. These messages will allow the development of material that provides guidance on the design and the implementation of CM in health organisations.

Trial registration number

Prospero CRD42017057753.

Keywords: frequent users, chronic conditions, interventions, case management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review will provide a middle-range theory of case management (CM) applicable across a range of primary care contexts and for various types of frequent users (FU) with chronic conditions.

There will be strong stakeholder engagement throughout the study to ensure findings are relevant to decision makers, practitioners and patients.

Knowledge users may use this theory to design and implement efficient CM in their health organisations and improve health outcomes for FU with chronic conditions.

Analysis will be limited to documents available to the research team.

Introduction

Worldwide statistics suggest that more than three-quarter (80%) of healthcare costs serve only a fraction of the population.1 2 Indeed, 1/10 of this global budget is allocated to hospital services targeted at answering complex healthcare needs.3 4 Thus, frequent users (FUs) of healthcare services account for a small proportion of the patient population, yet they use more than half of the healthcare and social services available.3 4 Frequent use of emergency services is a good indicator of frequent use of other healthcare services,5–7 and 5% of emergency department patients account for 30%–50% of all visits.8 9 Such frequent use is considered inappropriate for both patients and healthcare systems10 11 and could be avoided by providing adequate care upstream. Indeed, over 80% of FU of emergency services suffer from chronic conditions that should be cared for in primary ambulatory care.12

In line with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Multiple Chronic Conditions Research Network, complexity could be considered as a challenge in adjusting care to adequately address patients’ care needs.13 Patients with complex care needs often attempt, unsuccessfully, to fulfil their unmet health needs by using excessive, ineffective or potentially harmful healthcare and social services in an uncoordinated way. This results in poorer health indicators, high mortality rates and considerable costs to the health and social services system.14

High-level evidence depicts case management (CM) as a promising effective intervention targeted at improving management offered to FU and to save undue costs.8 15 16 The Case Management Society of America stipulates that CM efficacy and efficiency relies on the development of a facilitating network supporting the patient needs through implication of the patient himself and his advocate family, in cohesion with the healthcare professionals’ activities and mandates. .17 To reach this objective, the National Case Management Network of Canada18 proposed that CM should follow six standards of practice: (1) ensure patient identification and eligibility; (2) propose global assessment of needs; (3) establish individualised strategic action plan in accordance with the patient goals and priorities; (4) implement this action plan; (5) follow intervention plan in relation to the patient needs and progress; and (6) secure transition processes.

Three systematic reviews of quantitative studies have evaluated the effectiveness of interventions provided to FU. Eight of the 11 studies included in Althaus and colleagues8 review concluded that CM reduced emergency department costs and an apparent improvement in social and clinical outcomes. For their part, based on 12 studies evaluating the impact of CM on FU of the emergency department, Kumar and colleagues concluded that the majority of evidence points to the benefits of CM interventions.15 Finally, Soril and colleagues,19 who included 17 studies, 12 of which evaluated CM, revealed CM to be the more stringent evidence-based intervention that yielded moderate cost savings, though variable reductions in emergency department use.

However, CM is complex,20 21 because it often involves multiple caregivers, patients and family members interacting about several complex and variable health and social conditions, resulting in outcomes that are highly dependent on context and variable across the populations within studies.21 22 Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis underpinned that CM was not as effective as expected in ageing patients at risk of hospitalisation.23 Accordingly, as full theoretical explanation of successful conditions delineating CM practice in primary care has not been provided yet,24 there is an urgent need to address this gap in order to improve care of FU with chronic conditions.25

This review is aimed to develop a middle-range theory that explains how CM in primary care works to improve outcomes among FU with chronic conditions, for whom (ie, what types of FU with chronic conditions) and in what circumstances. Based on this aim, the following research questions will be answered: (1) what are the mechanisms that contribute, among FU with chronic conditions, to the desired effects of CM in primary care, that is, better integration of services, improved use and reduced costs in the healthcare system and improved patient-reported outcomes (self-management, experience of care and quality of life)?; (2) which FU with chronic conditions should CM target?; and (3) what are the contexts and circumstances of CM that generate these mechanisms?

Methods and analysis

Design

A realist synthesis (RS) study is being conducted between March 2017 and March 2018. RS is a theory-driven, qualitative approach to synthesising qualitative, quantitative and/or mixed methods evidence from complex interventions.26–28 The primary focus of RS is to explore the causal mechanisms that underlie interventions,29 and how contextual factors influence the link between these causal mechanisms and outcomes.30 This is done by configuring semipredictable (demiregularities)31 patterns of contexts, mechanisms and outcomes (CMO) from the included studies and using them to refine the ‘initial rough theory’.30 The resulting middle-range theory is close to the data yet sufficiently abstract to be applicable across similar interventions. Strengths of RS are fourfold: (1) oriented towards a theoretical perspective, (2) gather evidences from multiple sources, (3) promote stakeholders engagement and (4) optimise learning across policy, disciplinary and organisational domains.13 Results of this proposed RS will provide knowledge users with a deep understanding of CM and how best to implement it to be effective.32

The synthesis protocol for the current study has been registered with the PROSPERO database.33 The review process will follow the five stages of RS described by Pawson34: (1) focusing the scope of the RS; (2) searching for the evidence; (3) appraising the quality of evidence; (4) extracting the data; and (5) synthesising the evidence (figure 1). These steps are non-linear and interrelated; the RS process is one of continuous adjustment and refinement of the initial rough theory, as each element is interrogated with reference to the evidence found previously. Representatives of various stakeholder groups from all participating provinces (Saskatchewan, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador) will be engaged in the project on an RS committee.

Figure 1.

RS design. CM, case management; CMO, context, mechanism and outcomes; RS, realist synthesis.

Focusing the scope of the RS

A meeting with all the members of the RS team will be held to collectively develop the initial rough theory. The main findings of a ‘parent’ systematic review33 on interventions targeting FU with chronic conditions in primary care conducted by our team will be presented together with the four main components identified in documents about CM,35 36 research articles from this field37 38 and our previous work24: (1) case finding; (2) care planning; (3) coordination/integration of services; and (4) self-management support (figure 2). This will provide the starting point for a process of discussion and consensus building regarding an initial rough theory of CM. Drawing on external stakeholder expertise is strongly encouraged to focus the RS.39

Figure 2.

Template for the development of the middle-range theory about CM in primary care for FU in primary care. CM, case management; FU, frequent users of healthcare services.

The ‘initial rough theory’39 will provide a basic explanation of how and why CM works, for whom and in what circumstances and will guide the RS. This rough theory will take the form of one or more testable propositions describing intervention contexts (C), the mechanisms (M) they trigger and the resulting outcomes (O) or CMO configurations.

Searching for the evidence

Based on our ‘parent’ systematic review,33 we will start the searching with the included studies on CM interventions. However, many of these articles do not sufficiently describe CM components, key elements associated with successful CM or their contextual aspects.8 15 24 Accordingly, as RS supports inclusion of evidence from heterogeneous sources and an emphasis on iterative search processes,34 we will use a cluster searching40 to identify related studies and grey literature (eg, reports, web pages and news articles) relevant to each CM intervention. This will allow us to capture documents that could provide rich contextual and conceptual descriptions of these interventions.

For this cluster searching, we will search for relevant documents about CM interventions through: (1) reference list searches; (2) Scopus and Web of Science searches of the initial publication followed by examination of all citing manuscripts; (3) PubMed (OVID interface) search using the corresponding author’s name; (4) Google search (first two pages) for the title of the study; and (5) a review of the corresponding author’s ResearchGate and/or Academia.edu publications (to capture unpublished information such as abstracts and posters). All corresponding authors will be contacted by email to gather more information. The search process will continuously evolve as understanding of the subject matter deepens.

Appraising the quality of evidence

RS does not only rely on traditional quality assessment tools. Rather, the researchers have to critically reflect on all evidence and determine its relevance and robustness for the purposes of answering the review question. Two researchers will examine the quality (relevance and rigour) of all selected documents about the CM interventions. According to the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) group, two questions will be posed to appraise the quality of evidence: (1) can the section of data in a given document be used to contribute to theory building/testing (relevance)? and (2) were the methods used to generate this section of data credible and trustworthy (rigour)? The researchers will discuss together in case of doubt and will keep memos of their assessment that will be shared with the RS committee. Sections of data are considered because this process recognises that useful and ‘trustworthy nuggets of information’ may be obtained from research documents even when the overall quality of a study is low.32 34

Data extraction and data analysis

Data extraction and analysis will be done concurrently. The preliminary data extraction tool will be finalised with the input of the RS committee, piloted and revised as the review progresses to ensure relevant data are captured as the theory evolves and is refined. Data extracted will pertain to: (1) bibliographic information; (2) objectives, sample size and setting, research design and its appropriateness given the study objective, and potential of the design to bias the results; and (3) CMOs. When configuring CMOs, attention will be paid to extracting data pertaining to: (1) participant descriptions (age, sex, ethnicity, primary diagnosis and comorbidities); (2) intervention components or strategies (case finding, care planning, coordination/integration, self-management support and others); (3) proximal outcome(s) and their associated measure(s); (4) the inner (organisational setting, resources, team culture and characteristics of CM implementers) and outer contexts (policies, laws and standards); and (5) mechanisms triggered by the inner/outer contexts and how they may generate the proximal and final outcome(s). As previously described, the RS will focus on three categories of outcomes, namely the integration of services, the healthcare utilisation or costs and patient-reported outcomes (self-management, experience of care and quality of life); PDFs of the selected documents will be imported into NVivo (QSR*NVIVO V.10 software), a software for qualitative data analyses.41–43

To configure CMOs, we will first identify outcomes and then search for their associated mechanisms and contexts (backwards).39 To ensure the data extractors apply common processes and standards, they will collaborate on the data extraction for the first few CM interventions, focusing in particular on their understanding of CMO configurations. Once confident, they will each complete data extraction on the remaining CM interventions and meet each other to discuss and debate CMO configurations as needed.44 Relevant information from all data sources will be extracted and organised in an NVivo Project file to allow for analysis of the CMO configurations.

As recommended by the RAMESES group, analysis will be pursued using an abductive reasoning approach, for example, an iterative process by which a constant back and forth between the theory and the observations is adopted to identify the propositions to inform the evolving theory. 45 46 CMO configurations will be analysed for patterns and relationships (demiregularities). As per the RS standards, additional literature may be collected to help revise CMO configurations and refine the demiregularities and the middle-range theory.44 We will use matrix coding query features of NVivo to identify patterns in CMO configurations, first within each intervention and then across interventions. Attention will be given to understanding why certain mechanisms generate different outcomes in different contexts or among different types of FU with chronic conditions. Analysis of CMO configurations will help us confirm, refute or modify, or add to the components of our initial rough theory, and ultimately produce a refined theory explaining how and why CM works, in particular contexts, for particular FU with chronic conditions. The RS committee will discuss the CMO configurations and the developing middle-range theory. Throughout this step, included documents about CM interventions will be reread to check if any data were missed that might help refine the theory.47

A final middle-range theory will be developed. It will comprise multiple demiregularities based on CMO configurations, such as explanations on how and why one type of intervention works in a particular context to achieve an expected outcome among FU with chronic conditions. This middle-range theory will provide context-sensitive explanations about how CM works and will thus inform practice and policy.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required for an RS, but publication guidelines on RS will follow the RAMESES48 methodology. Knowledge translation will be built on strength of stakeholders’ engagement (patients, practitioners and decision/policy makers) throughout the research synthesis process. These stakeholders will be members of the RS committee that will be responsible for key decisions during data collection, analysis/interpretation and dissemination. Based on the review findings, we will develop and disseminate messages tailored to various relevant stakeholder groups: (1) for the public: news release in media outlets; (2) for decision/policy makers and practitioners: brief reports tailored to decision/policy makers and various practitioner audiences; results will also be presented at Canadian meetings for each discipline; (3) for researchers: presentation of the results at international meetings and publications in peer-reviewed journals; and (4) for all audiences: webinars and presentations at the research day of the Pan-Canadian SPOR Network in Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations. These messages will allow the development of material that provides guidance on the design and the implementation of CM in health organisations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Unité de Recherche Clinique et Épidémiologique (URCE) of the Centre de recherche du CHU de Sherbrooke and the Quebec SPOR-SUPPORT Unit for their support in coordinating the preparation and revisions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: CH and M-CC conceived, designed and drafted the protocol manuscript. KA-B, NM, FB, PP, PB, VS, FL, LG and PM critically revised the manuscript for methodological and academic content. AG, MC, CC, MB and LE (decision makers), JG, BD and NR (clinicians), VS, CS, GG and MW (patients) revised the manuscript for content expertise. ML will implement the realist synthesis under the supervision of CH and M-CC. All authors read, provided feedback and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number 150585 and other partners such as the Clinical Stabilization Fund Management, the Département de médecine de famille de l’Université de Sherbrooke, Centre de recherche du CHUS, Décanat de la recherche de l’Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, the Réseau-1 Québec and the Institut universitaire de première ligne de l’Estrie.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money–controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1521–3. 10.1056/NEJMp0907185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. Caring for people with long term conditions: an education framework for community matrons and case managers. United Kingdom: Department of Health - Long term conditions team, 2006. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4134012.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Commission de la réforme des services publics de l'Ontario. Des services publics pour la population ontarienne: cap sur la viabilité et l’excellence. Ottawa: Gouvernement de l’Ontario, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wodchis W, 2013. High cost users: driving value with a patient-centered health system. Health Links and Beyond: The Long and Winding Road to Person-Centred Care, Ontario, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doupe MB, Palatnick W, Day S, et al. Frequent users of emergency departments: developing standard definitions and defining prominent risk factors. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:24–32. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun BC, Burstin HR, Brennan TA. Predictors and outcomes of frequent emergency department users. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:320–8. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zuckerman S, Shen YC. Characteristics of occasional and frequent emergency department users: do insurance coverage and access to care matter? Med Care 2004;42:176–82. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108747.51198.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:41–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blank FS, Li H, Henneman PL, et al. A descriptive study of heavy emergency department users at an academic emergency department reveals heavy ED users have better access to care than average users. J Emerg Nurs 2005;31:139–44. 10.1016/j.jen.2005.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, et al. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:1–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruger JP, Richter CJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Analysis of costs, length of stay, and utilization of emergency department services by frequent users: implications for health policy. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:1311–7. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb01919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Billings J, Raven MC. Dispelling an urban legend: frequent emergency department users have substantial burden of disease. Health Aff 2013;32:2099–108. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grimshaw J. A knowledge synthesis chapter. 2010. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/knowledge_synthesis_chapter_e.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2016).

- 14. Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff 2011;30:2437–48. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med 2013;44:717–29. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123660 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Case management Society of America. Home page. . www.cmsa.org (accessed 21 Jul 2016).

- 18. National Case Management Network of Canada . Canadian standards of practice in case management. Connect, collaborate and communicate the power of case management, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123660 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007;334:455–9. 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shepperd S, Lewin S, Straus S, et al. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000086. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pawson R. Nothing as Practical as a Good Theory. Evaluation 2003;9:471–90. 10.1177/1356389003094007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, et al. Effectiveness of Case Management for 'At Risk' Patients in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132340 10.1371/journal.pone.0132340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Lambert M, et al. Effectiveness of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012353. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Knowledge user engagement. 2016. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49505.html (accessed 21 Jul 2016).

- 26. Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: The promise of `realist synthesis'. Evaluation 2002;8:340–58. 10.1177/135638902401462448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist synthesis: an introduction. . ESRC Research Methods Programme, University of Manchester. RMP Methods Paper 2 2004:http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/publications/RMPmethods2.pdf%20. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. Synthesizing Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence: A Guide to Methods. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. 10.1258/1355819054308576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lawson T. Economics and Reality: Routledge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pawson R. Digging for nuggets: How ‘Bad’ research can yield ‘Good’ evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2006;9:127–42. 10.1080/13645570600595314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Aubrey-Bassler K, et al. Case management in primary care to improve outcomes among frequent users of health care services with chronic conditions: a realist synthesis of what works, for whom and under what circumstances? PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews, 2017. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017057753. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective: Sage publications Ltd, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ross S, Curry N, Goodwin N. Case management: What it is and how it can best be implemented: The King's Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Challis D, Hughes J, Berzins K, Reilly S, Abell J, Stewart K. 2010. Self-care and case management in long-term conditions: the effective management of critical interfaces. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme.

- 37. Freund T, Peters-Klimm F, Rochon J, et al. Primary care practice-based care management for chronically ill patients (PraCMan): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN56104508]. Trials 2011;12:163 10.1186/1745-6215-12-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, et al. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:177–87. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Medicine 2013;11:1–14. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Booth A, Harris J, Croot E, et al. Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual “richness” for systematic reviews of complex interventions: case study (CLUSTER). BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–14. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:12. 10.1186/1472-6920-10-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomas DR, Thomas YL. Interventions to reduce injuries when transferring patients: a critical appraisal of reviews and a realist synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:1381–94. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wong G, Pawson R, Owen L. Policy guidance on threats to legislative interventions in public health: a realist synthesis. BMC Public Health 2011;11:1–11. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wong GGT, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Quality standards for meta-narrative reviews (for researchers and peer-reviewers). 2014. http://www.ramesesproject.org/media/MNR_qual_standards_researchers.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2016).

- 45. Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q 2012;90:311–46. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eastwood JG, Kemp LA, Jalaludin BB. Realist theory construction for a mixed method multilevel study of neighbourhood context and postnatal depression. Springerplus 2016;5:1081 10.1186/s40064-016-2729-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nyssen OP, Taylor SJ, Wong G, et al. Does therapeutic writing help people with long-term conditions? Systematic review, realist synthesis and economic considerations. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–368. 10.3310/hta20270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1005–22. 10.1111/jan.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.