Abstract

Objectives

To explore the existence and strength of a relationship between hospital volume and mortality, to estimate minimum volume thresholds and to assess the potential benefit of centralisation of services.

Design

Observational population-based study using complete German hospital discharge data (Diagnosis-Related Group Statistics (DRG Statistics)).

Setting

All acute care hospitals in Germany.

Participants

All adult patients hospitalised for 1 out of 25 common or medically important types of inpatient treatment from 2009 to 2014.

Main outcome measure

Risk-adjusted inhospital mortality.

Results

Lower inhospital mortality in association with higher hospital volume was observed in 20 out of the 25 studied types of treatment when volume was categorised in quintiles and persisted in 17 types of treatment when volume was analysed as a continuous variable. Such a relationship was found in some of the studied emergency conditions and low-risk procedures. It was more consistently present regarding complex surgical procedures. For example, about 22 000 patients receiving open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm were analysed. In very high-volume hospitals, risk-adjusted mortality was 4.7% (95% CI 4.1 to 5.4) compared with 7.8% (7.1 to 8.7) in very low volume hospitals. The

minimum volume above which risk of death would fall below the average mortality was estimated as 18 cases per year. If all hospitals providing this service would perform at least 18 cases per year, one death among 104 (76 to 166) patients could potentially be prevented.

Conclusions

Based on complete national hospital discharge data, the results confirmed volume–outcome relationships for many complex surgical procedures, as well as for some emergency conditions and low-risk procedures. Following these findings, the study identified areas where centralisation would provide a benefit for patients undergoing the specific type of treatment in German hospitals and quantified the possible impact of centralisation efforts.

Keywords: volume-outcome relationship, hospital discharge data, in-hospital mortality, germany

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this study is the use of current and complete national hospital discharge data, covering virtually every patient who underwent one out of the studied types of treatment during the study period.

As hospital volumes vary widely among German acute care hospitals, this is a proper setting to study volume–outcome relationships.

In contrast to most other volume–outcome studies, the present approach includes the calculation of minimum volume thresholds along with an assessment of the possible impact of centralisation efforts on the population.

Within this observational retrospective study, the statistical association between volume and outcome was tested on administrative data.

As information available from administrative data is limited, it is possible that unmeasured differences in disease severity, comorbidity or appropriateness of patient selection may partly explain the association between volume and outcome.

This study did not consider hospital characteristics like teaching status, type of ownership or location.

Introduction

The relationship between hospital volume and patient outcomes has been widely studied. For many inpatient treatments, a higher volume was found to be associated with better outcomes, such as for high-risk surgical procedures, medical conditions or elective low-risk surgery.1–10 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were conducted to aggregate results into a broader frame of knowledge.11–14 However, the heterogeneity of methods used impairs conclusions from meta-analyses. In particular, the categorisation of high-volume hospitals varies according to the geographical context.15 16 Moreover, many studies include only samples of patients or are restricted to patients with a specific type of insurance or within a delimited geographic area. Therefore, it is often uncertain if the association of volume and outcome found in one study may be generalisable to the whole population affected or even to populations in other countries with different healthcare systems. Finally, studies reporting better outcome in relation to higher volume often lack an assessment of the clinical and policy significance of their findings.16

To date, the volume–outcome relationship in Germany has been studied only for few inpatient services, such as pancreatic resection, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, hip fracture or treatment of very low birth weight infants.17–20 The German acute care hospital market is characterised by a relative overcapacity of hospital beds and high hospitalisation rates.21 Volumes of inpatient treatments vary widely among about 1600 German acute care hospitals.22 In 2004, minimum volume thresholds for specific types of inpatient treatment were established. However, it has been found that many hospitals did not adhere to this regulation, and the debate about the underlying evidence remains controversial.23–25

Efforts to improve quality of care by centralisation of services need to rely on evidence that higher volume is associated with better outcome. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relation of hospital volume and outcome in the German hospital market by using complete national hospital discharge data. For a broad range of common or medically important inpatient services, the existence and strength of a relationship between volume and mortality were analysed. Where lower mortality in relation to higher volume was observed, minimum volume thresholds, above which mortality would be reduced, were estimated. Impact measures were calculated to assess the potential benefit of centralisation efforts.

Methods

Data

German acute care hospitals are obliged to submit their inpatient discharge data annually to a nationwide database, which is available for research purposes. This database (Diagnosis-Related Group Statistics (DRG Statistics) provided by the Research Data Centres of the Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the ‘Länder’) contains discharge information on every inpatient episode, covering patients of all types of insurance. Principal and secondary diagnoses are coded according to the German adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-GM). Procedures are coded according to the German procedure coding system (OPS, Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel). Information on sex, age, source of admission, discharge disposition and length of stay is also included. Based on an anonymised hospital identifier, every inpatient episode can be assigned to the treating hospital.26 The analyses included data of the years 2009–2014. Data were accessed via controlled remote data analysis.

Patient population

To study a broad range of hospital services, five groups of inpatient treatments comprising 25 single conditions or procedures were analysed:

Common emergency conditions (6)

Elective heart and thoracic surgery (4)

Elective major visceral surgery (6)

Elective vascular surgery (4)

Elective low-risk surgery (5)

Each type of treatment was defined by specific inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to minimise confounding by differences in case-mix. Treatments for emergency conditions (eg, acute myocardial infarction) were restricted to direct admissions by excluding patients who had been transferred-in from another acute care hospital. Elective surgical treatments were defined by restriction to certain medical indications (eg, colorectal resection for carcinoma) or exclusion of complicated constellations (eg, aortic valve replacement excluding combined other heart surgery). All definitions refer to adult patients aged 20 years and older. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the online supplementary table 1 .

bmjopen-2017-016184supp001.pdf (78.1KB, pdf)

Hospital volume

Volume of patients treated by a hospital was calculated for each year of observation corresponding to the respective definition of a studied type of treatment. Aiming to compare results in the context of the current literature, hospitals were ranked into quintiles of approximately equal case numbers according to their annual volume. This ranking was done separately for each year for observation, allowing the rank of one hospital to change from 1 year to another, if volume changed over time. Additionally, annual hospital volume was analysed as a continuous variable.

Within a sensitivity analysis hospital volume was additionally determined on the basis of wider case definitions in order to fully consider all treatments which might enhance a hospital’s experience regarding a specific condition or procedure (eg, all colorectal resections regardless from medical indication). This approach led to a higher estimation of annual volume per hospital in most cases and resulted in a slightly different ranking of hospitals. Within this analysis, restrictions in case definition, as described above, were subsequently applied for outcome measurement.

Outcome measure, risk adjustment and statistical analysis

Inhospital mortality, defined as death before discharge, was studied as outcome measure. Observed and risk-adjusted mortality were stratified by volume quintiles.

Risk-adjusted mortality for each volume quintile was calculated by using generalised estimating equations (GEE) with a logit link function, accounting for clustering of patients within hospitals. Using the pooled data of the entire observation period, one GEE model was fitted for each studied treatment. Depending on the type of treatment, models included comorbidities, which most likely have been present on admission (eg, diabetes, chronic liver disease), specific indicators of disease severity (eg, ST-elevation myocardial infarction) or extension of surgery (eg, concomitant resection of other visceral organs in patients with pancreatic resection). Five-year age groups, sex and calendar year of treatment were considered within each model. The definitions and treatment-specific applications of covariates for risk adjustment are displayed in the online supplementary tables 2 and 3.

In order to estimate the independent impact of hospital volume on inhospital mortality, hospital volume was subsequently entered into each model, taken as a categorically variable. ORs for inhospital death by hospital volume quintile were calculated.

To further explore the relationship between volume and outcome, GEE models with volume as a continuous variable were fitted for each treatment. In a first step, hospital volume was taken as the only predictor (simple model). In a second step, the treatment-specific covariates, as described above, were entered into the model (full model), and ORs for inhospital death according to an increment of one case, as well as of 50 cases per year, were calculated.

Where the regression coefficient of a one-case increment of hospital volume remained statistically significant after consideration of covariates, minimum volume thresholds were estimated from the simple model using Bender’s Value of Acceptable Risk Limit.27 This value is calculated from the function of the logistic regression coefficient of hospital volume. It denotes the threshold where mortality is expected to fall below a predefined acceptable risk. The acceptable risk was set to the average mortality of the respective treatment during the observation period.

The clinical relevance of thresholds was assessed by the population impact number (PIN). The PIN was calculated as reciprocal of the difference between the average mortality risk in the entire patient population and the adjusted risk among patients treated by hospitals with volumes above the threshold (population-based risk difference (PRD)).28 In the context of this study, the PIN can be interpreted as average number of patients within a treatment group among whom one death is attributable to treatment by a below-threshold volume hospital, due to excess risk of mortality in these hospitals. In other words, among this number of patients, one death could hypothetically be prevented if all hospitals providing the respective inpatient service had annual volumes equal or higher than the threshold.

The level of statistical significance was set to 0.05. The analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Reporting guideline

Reporting of this analysis adheres to the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data statement.29

Results

Common emergency conditions

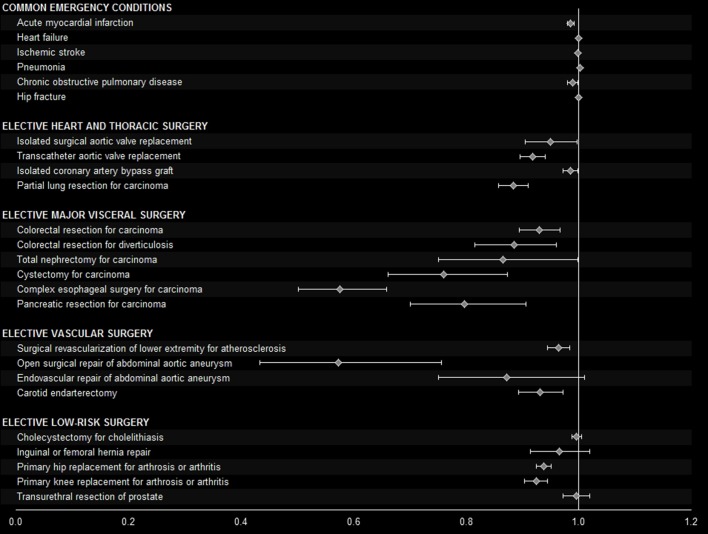

Lower inhospital mortality in association with higher hospital volume was observed in four out of the six studied types of common emergency treatment when volume was categorised in quintiles and persisted in two types of treatment when volume was analysed as a continuous variable.

From 2009 to 2014, nearly 1.1 million patients were treated for acute myocardial infarction (table 1). Risk-adjusted mortality was 8.9% (95% CI 8.8 to 9.0) in the very high volume quintile versus 11.4% (11.3 to 11.6) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Adjusted ORs of inhospital death were significantly reduced in the low to very high volume quintiles when compared with the very low volume quintile (table 2). A statistically significant effect of volume on mortality was also observed when volume was analysed as a continuous variable. An increment of 50 cases per year was associated with reduced odds of death (figure 2). The minimum hospital volume where risk of mortality would fall below the average mortality of 9.8% was calculated as 309 cases per year. Stratification by this threshold resulted in a PRD of 0.7% (0.7 to 0.8) and a PIN of 137 (127 to 149, table 3). This means that, out of 137 patients hospitalised for acute myocardial infarction, one death would be prevented if annual volumes in treating hospitals were at least 309.

Table 1.

Number of patients and hospitals by volume quintile

| Hospital volume quintile | |||||||||||

| Very low | Low | Medium | High | Very high | |||||||

| Common emergency conditions | |||||||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | No of patients | 219 178 | 219 291 | 219 189 | 219 778 | 220 805 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 763 | 198 | 121 | 88 | 54 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 43 | (20–71) | 184 | (154–215) | 303 | (274–331) | 412 | (387–450) | 594 | (534–732) | |

| Heart failure | No of patients | 463 352 | 463 883 | 463 283 | 464 586 | 465 401 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 608 | 263 | 184 | 136 | 87 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 139 | (63–189) | 290 | (260–321) | 418 | (374–461) | 570 | (518–613) | 804 | (703–950) | |

| Ischaemic stroke | No of patients | 244 125 | 244 272 | 244 299 | 243 725 | 246 858 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 915 | 155 | 96 | 70 | 42 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 28 | (10–62) | 259 | (213–310) | 427 | (383–471) | 577 | (542–625) | 865 | (766–1028) | |

| Pneumonia | No of patients | 258 016 | 257 688 | 258 010 | 258 051 | 259 391 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 630 | 255 | 186 | 140 | 84 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 73 | (25–107) | 167 | (150–183) | 229 | (211–249) | 304 | (279–331) | 447 | (396–523) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No of patients | 230 629 | 230 793 | 231 093 | 230 258 | 232 476 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 612 | 264 | 182 | 125 | 61 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 67 | (33–92) | 144 | (126–163) | 209 | (187–233) | 299 | (262–337) | 546 | (455–702) | |

| Hip fracture | No of patients | 142 041 | 142 082 | 141 910 | 141 658 | 143 271 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 609 | 232 | 172 | 133 | 88 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 43 | (6–64) | 101 | (93–110) | 137 | (128–146) | 176 | (164–190) | 244 | (221–283) | |

| Elective heart and thoracic surgery | |||||||||||

| Isolated surgical aortic valve replacement | No of patients | 10 275 | 10 238 | 10 627 | 10 066 | 11 397 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 33 | 17 | 14 | 10 | 7 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 54 | (37–71) | 101 | (93–108) | 132 | (124–138) | 172 | (159–188) | 246 | (227–283) | |

| Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | No of patients | 9915 | 10 009 | 9926 | 9935 | 10 980 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 48 | 17 | 12 | 9 | 6 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 31 | (12–50) | 98 | (69–123) | 141 | (99–161) | 169 | (142–228) | 286 | (233–328) | |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass graft | No of patients | 35 648 | 36 967 | 36 047 | 37 221 | 37 807 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 48 | 18 | 14 | 11 | 8 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 120 | (1–230) | 353 | (318–375) | 436 | (407–465) | 561 | (518–585) | 729 | (669–824) | |

| Partial lung resection for carcinoma | No of patients | 14 655 | 14 766 | 14 626 | 14 872 | 15 064 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 260 | 48 | 27 | 17 | 9 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 5 | (2–14) | 49 | (43–59) | 89 | (79–98) | 137 | (122–160) | 272 | (208–313) | |

| Elective major visceral surgery | |||||||||||

| Colorectal resection for carcinoma | No of patients | 66 058 | 66 089 | 66 119 | 66 185 | 66 451 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 492 | 218 | 153 | 112 | 71 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 23 | (14–32) | 50 | (45–55) | 72 | (66–78) | 97 | (91–105) | 141 | (126–165) | |

| Colorectal resection for diverticulosis | No of patients | 35 828 | 35 821 | 35 810 | 35 872 | 36 032 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 487 | 215 | 154 | 114 | 73 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 13 | (7–18) | 28 | (25–30) | 39 | (36–42) | 52 | (48–56) | 74 | (68–86) | |

| Total nephrectomy for carcinoma | No of patients | 13 582 | 13 569 | 13 570 | 13 600 | 13 766 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 307 | 90 | 65 | 47 | 31 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 5 | (2–13) | 25 | (23–27) | 35 | (33–37) | 48 | (45–52) | 67 | (60–76) | |

| Cystectomy for carcinoma | No of patients | 8706 | 8702 | 8761 | 8734 | 8832 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 177 | 78 | 56 | 39 | 24 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 9 | (5–12) | 18 | (17–20) | 26 | (24–28) | 36 | (34–40) | 57 | (51–68) | |

| Complex oesophageal surgery for carcinoma | No of patients | 3625 | 3625 | 3639 | 3550 | 3769 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 228 | 71 | 43 | 23 | 10 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 2 | (1–4) | 8 | (7–10) | 14 | (12–16) | 25 | (21–29) | 54 | (42–67) | |

| Pancreatic resection for carcinoma | No of patients | 6886 | 6915 | 6880 | 6854 | 7020 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 322 | 117 | 71 | 41 | 17 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 3 | (2–5) | 10 | (9–11) | 16 | (14–18) | 27 | (23–33) | 57 | (46–72) | |

| Elective vascular surgery | |||||||||||

| Surgical lower extremity revascularisation for atherosclerosis | No of patients | 49 239 | 49 385 | 49 467 | 49 086 | 49 997 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 348 | 113 | 79 | 57 | 37 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 21 | (7–39) | 72 | (65–80) | 102 | (95–112) | 143 | (131–158) | 210 | (185–243) | |

| Open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | No of patients | 4422 | 4425 | 4430 | 4420 | 4530 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 239 | 81 | 50 | 33 | 18 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 3 | (1–4) | 9 | (7–10) | 15 | (13–17) | 21 | (19–25) | 39 | (33–46) | |

| Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | No of patients | 8281 | 8338 | 8288 | 8309 | 8462 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 219 | 81 | 52 | 34 | 20 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 6 | (3–9) | 17 | (15–19) | 26 | (24–30) | 40 | (36–45) | 64 | (57–75) | |

| Carotid endarterectomy |

No of patients | 32 345 | 32 267 | 32 460 | 32 017 | 33 081 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 317 | 101 | 67 | 47 | 30 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 16 | (6–27) | 52 | (46–59) | 80 | (73–87) | 113 | (104–123) | 165 | (148–195) | |

| Elective low-risk surgery | |||||||||||

| Cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis | No of patients | 177 346 | 177 411 | 177 835 | 177 199 | 178 752 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 450 | 232 | 178 | 140 | 94 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 71 | (44–91) | 128 | (118–137) | 166 | (157–176) | 210 | (196–224) | 286 | (264–331) | |

| Inguinal or femoral hernia repair | No of patients | 178 992 | 179 169 | 179 285 | 179 338 | 179 911 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 471 | 247 | 186 | 142 | 84 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 68 | (45–86) | 120 | (111–129) | 160 | (150–171) | 208 | (194–224) | 312 | (274–377) | |

| Primary hip replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | No of patients | 175 918 | 175 797 | 176 313 | 175 834 | 177 287 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 608 | 226 | 135 | 82 | 42 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 49 | (25–71) | 128 | (111–146) | 213 | (190–242) | 351 | (314–388) | 619 | (522–768) | |

| Primary knee replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | No of patients | 168 312 | 168 479 | 168 415 | 168 015 | 169 623 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 517 | 222 | 143 | 94 | 51 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 56 | (36–75) | 125 | (112–140) | 195 | (176–215) | 291.5292 | (267–324) | 477 | (421–632) | |

| Transurethral resection of prostate | No of patients | 86 404 | 86 934 | 86 199 | 86 967 | 87 412 | |||||

| No of hospitals | 247 | 104 | 77 | 59 | 40 | ||||||

| Median annual volume (IQR) | 60 | (23–92) | 139 | (128–150) | 186 | (172–199) | 243 | (227–262) | 331 | (303–380) | |

No of hospitals: mean number of hospitals in quintile per year providing the respective inpatient service; IQR, IQR within the quintile (due to data protection regulations the minimum and maximum values cannot be displayed).

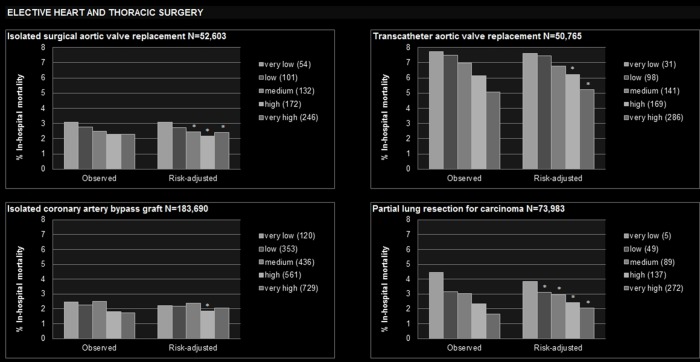

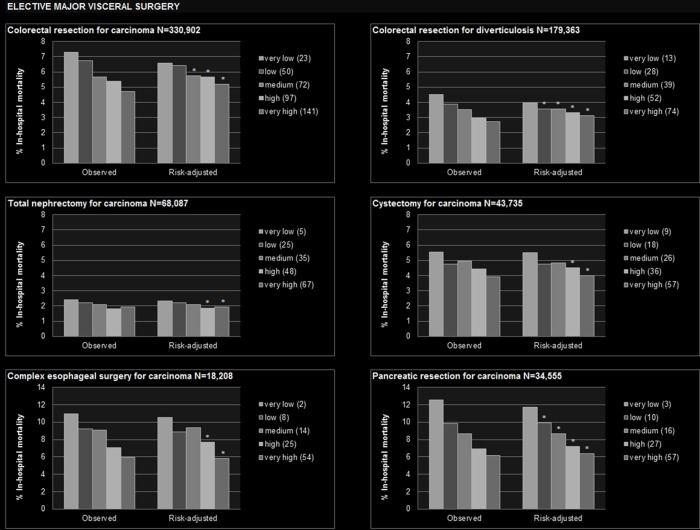

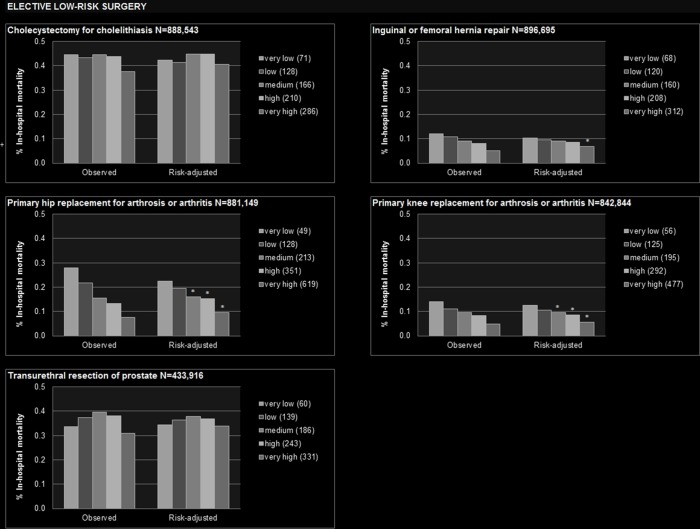

Figure 1.

Observed and risk-adjusted inhospital mortality by hospital volume quintile. *Statistically significant lower than very low volume quintile. +Statistically significant higher than very low volume quintile. Numbers displayed in the legend of each graph denote the median annual hospital volume within the respective volume quintile. Covariates used for risk adjustment are displayed in the online supplementary table 3.

Table 2.

ORs of inhospital death according to volume quintile

| Hospital volume quintile | ||||||||||

| Very low | Low | Medium | High | Very high | ||||||

| Common emergency conditions | ||||||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.71 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.84* | (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.75* | (0.72 to 0.78) | 0.73* | (0.7 to 0.76) | 0.69* | (0.66 to 0.72) | |

| Heart failure | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.81 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.99 | (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.96* | (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.95* | (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.91* | (0.88 to 0.94) | |

| Ischaemic stroke | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.72 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.90* | (0.87 to 0.94) | 0.87* | (0.83 to 0.9) | 0.94* | (0.91 to 0.98) | 0.94* | (0.91 to 0.98) | |

| Pneumonia | Crude OR | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.08 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.10 | (1.07 to 1.13) | 1.17 | (1.14 to 1.21) | 1.13 | (1.09 to 1.16) | 1.08 | (1.04 to 1.11) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Crude OR | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 0.66 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.09 | (1.06 to 1.14) | 1.08 | (1.04 to 1.12) | 0.94* | (0.90 to 0.98) | 0.70* | (0.65 to 0.75) | |

| Hip fracture | Crude OR | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.00 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.07 | (1.03 to 1.12) | 1.07 | (1.03 to 1.11) | 1.10 | (1.06 to 1.15) | 1.01 | (0.97 to 1.06) | |

| Elective heart and thoracic surgery | ||||||||||

| Isolated surgical aortic valve replacement | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.74 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.87 | (0.69 to 1.10) | 0.78* | (0.62 to 0.99) | 0.69* | (0.54 to 0.87) | 0.77* | (0.61 to 0.97) | |

| Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.64 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.98 | (0.69 to 1.1) | 0.87* | (0.62 to 0.99) | 0.79* | (0.54 to 0.87) | 0.65* | (0.61 to 0.97) | |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass graft | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.70 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.98 | (0.81 to 1.17) | 1.08 | (0.90 to 1.28) | 0.82* | (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.92 | (0.76 to 1.11) | |

| Partial lung resection for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.37 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.77* | (0.67 to 0.90) | 0.73* | (0.63 to 0.85) | 0.58* | (0.50 to 0.69) | 0.49* | (0.41 to 0.58) | |

| Elective major visceral surgery | ||||||||||

| Complex oesophageal surgery for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.51 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.81* | (0.68 to 0.96) | 0.85 | (0.72 to 1.01) | 0.67* | (0.56 to 0.82) | 0.47* | (0.38 to 0.58) | |

| Pancreatic resection for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.46 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.80* | (0.71 to 0.92) | 0.68* | (0.59 to 0.77) | 0.54* | (0.46 to 0.62) | 0.46* | (0.39 to 0.54) | |

| Colorectal resection for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.63 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.97 | (0.91 to 1.02) | 0.85* | (0.80 to 0.90) | 0.83* | (0.78 to 0.88) | 0.75* | (0.70 to 0.80) | |

| Colorectal resection for diverticulosis | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.60 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.87* | (0.80 to 0.95) | 0.87* | (0.79 to 0.95) | 0.80* | (0.72 to 0.88) | 0.74* | (0.67 to 0.82) | |

| Total nephrectomy for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.80 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.95 | (0.79 to 1.13) | 0.89 | (0.75 to 1.06) | 0.78* | (0.64 to 0.94) | 0.80* | (0.67 to 0.97) | |

| Cystectomy for carcinoma | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.70 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.85* | (0.73 to 0.98) | 0.86 | (0.74 to 1.00) | 0.80* | (0.69 to 0.93) | 0.69* | (0.58 to 0.82) | |

| Elective vascular surgery | ||||||||||

| Surgical lower extremity revascularisation for atherosclerosis | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.75 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88* | (0.81 to 0.96) | 0.85* | (0.78 to 0.94) | 0.82* | (0.75 to 0.90) | 0.82* | (0.75 to 0.91) | |

| Open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.52 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.71* | (0.59 to 0.84) | 0.76* | (0.63 to 0.91) | 0.60* | (0.50 to 0.72) | 0.55* | (0.45 to 0.68) | |

| Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.17 | 0.80 | 0.82 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.81 | (0.63 to 1.04) | 1.26 | (1.00 to 1.59) | 0.93 | (0.72 to 1.19) | 0.91 | (0.68 to 1.21) | |

| Carotid endarterectomy | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.66 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.92 | (0.77 to 1.09) | 0.89 | (0.75 to 1.05) | 0.90 | (0.76 to 1.06) | 0.77* | (0.64 to 0.93) | |

| Elective low-risk surgery | ||||||||||

| Cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.84 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.98 | (0.87 to 1.09) | 1.06 | (0.95 to 1.19) | 1.07 | (0.95 to 1.19) | 0.95 | (0.85 to 1.08) | |

| Inguinal or femoral hernia repair | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.43 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.94 | (0.77 to 1.14) | 0.90 | (0.72 to 1.11) | 0.83 | (0.66 to 1.04) | 0.66* | (0.51 to 0.86) | |

| Transurethral resection of prostate | Crude OR | 1.00 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 0.92 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.06 | (0.89 to 1.25) | 1.11 | (0.93 to 1.32) | 1.08 | (0.90 to 1.28) | 0.98 | (0.82 to 1.18) | |

| Primary hip replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.27 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.87* | (0.75 to 1.00) | 0.70* | (0.60 to 0.82) | 0.67* | (0.56 to 0.79) | 0.41* | (0.33 to 0.51) | |

| Primary knee replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | Crude OR | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.35 | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.84 | (0.69 to 1.02) | 0.76* | (0.62 to 0.94) | 0.68* | (0.54 to 0.85) | 0.45* | (0.34 to 0.58) | |

Covariates used for risk adjustment are displayed in the online supplementary table 3.

*Statistically significantly lower than reference category (very low volume).

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of inhospital death according to an increment of hospital volume of 50 cases per year. Whiskers indicate 95% CI. Covariates used for risk-adjustment are displayed in the online supplementary appendixe table 3.

Table 3.

Minimum volume threshold estimation and assessment of population impact

| Logistic regression coefficients of hospital volume | VARL Minimum volume threshold (95% CI) | Average mortality in population | Adjusted mortality if volume ≥ VARL (95% CI) |

Population-based risk difference (95% CI) | PIN Population impact number (95% CI) | ||||

| Simple model | Full model | ||||||||

| β | p | β | p | ||||||

| Common emergency conditions | |||||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | −0.0003 | <0.001 | −0.0003 | <0.001 | 309 (288 to 330) | 9.8% | 9.1% (9.0 to 9.2) | 0.7% (0.7 to 0.8) | 137 (127 to 149) |

| Heart failure | −0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.0000 | 0.358 | – | 8.9% | |||

| Ischaemic stroke | −0.0002 | 0.000 | 0.0000 | 0.025 | – | 6.9% | |||

| Pneumonia | 0.0000 | 0.003 | 0.0000 | <0.001 | – | 11.6% | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | −0.0003 | 0.039 | −0.0002 | 0.026 | 271 (240 to 301) | 4.2% | 3.6% (3.5 to 3.6) | 0.6% (0.5 to 0.6) | 170 (158 to 185) |

| Hip fracture | 0.0000 | 0.138 | 0.0000 | 0.828 | – | 5.5% | |||

| Elective heart and thoracic surgery | |||||||||

| Isolated surgical aortic valve replacement | −0.0014 | 0.001 | −0.0010 | 0.039 | 147 (111 to 182) | 2.6% | 2.4% (2.2 to 2.6) | 0.2% (0.0 to 0.3) | 516 (288 to 2589) |

| Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | −0.0024 | <0.001 | −0.0017 | <0.001 | 157 (142 to 171) | 6.6% | 5.8% (5.5 to 6.2) | 0.8% (0.5 to 1.0) | 133 (101 to 193) |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass graft | −0.0007 | <0.001 | −0.0003 | 0.024 | 475 (430 to 521) | 2.1% | 2.0% (1.9 to 2.1) | 0.2% (0.1 to 0.2) | 658 (445 to 1271) |

| Partial lung resection for carcinoma | −0.0034 | <0.001 | −0.0025 | <0.001 | 108 (95 to 120) | 2.9% | 2.3% (2.1 to 2.5) | 0.6% (0.5 to 0.7) | 168 (137 to 217) |

| Elective major visceral surgery | |||||||||

| Colorectal resection for carcinoma | −0.0023 | <0.001 | −0.0014 | <0.001 | 82 (76 to 88) | 6.0% | 5.4% (5.3 to 5.5) | 0.5% (0.4 to 0.6) | 197 (167 to 241) |

| Colorectal resection for diverticulosis | −0.0049 | <0.001 | −0.0025 | 0.003 | 44 (38 to 49) | 3.5% | 3.2% (3.1 to 3.4) | 0.3% (0.2 to 0.4) | 364 (269 to 564) |

| Total nephrectomy for carcinoma | −0.0032 | 0.012 | −0.0029 | 0.047 | 40 (24 to 56) | 2.1% | 1.9% (1.7 to 2.0) | 0.2% (0.1 to 0.3) | 459 (295 to 1056) |

| Cystectomy for carcinoma | −0.0054 | <0.001 | −0.0055 | <0.001 | 31 (23 to 39) | 4.7% | 4.3% (4.0 to 4.6) | 0.4% (0.2 to 0.7) | 227 (150 to 480) |

| Complex oesophageal surgery for carcinoma | −0.0105 | <0.001 | −0.0111 | <0.001 | 22 (17 to 28) | 8.5% | 6.3% (5.7 to 6.9) | 2.1% (1.6 to 2.6) | 47 (38 to 62) |

| Pancreatic resection for carcinoma | −0.0049 | <0.001 | −0.0045 | 0.001 | 29 (21 to 37) | 8.8% | 6.6% (6.2 to 7.2) | 2.2% (1.7 to 2.6) | 46 (39 to 58) |

| Elective vascular surgery | |||||||||

| Surgical lower extremity revascularisation for atherosclerosis | −0.0011 | <0.001 | −0.0007 | <0.001 | 123 (102 to 144) | 3.0% | 2.8% (2.7 to 2.9) | 0.2% (0.1 to 0.3) | 561 (387 to 1024) |

| Open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | −0.0129 | <0.001 | −0.0112 | <0.001 | 18 (14 to 23) | 6.0% | 5.0% (4.6 to 5.5) | 1.0% (0.6 to 1.3) | 104 (76 to 166) |

| Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm | −0.0031 | 0.014 | −0.0028 | 0.069 | – | 1.7% | |||

| Carotid endarterectomy | −0.0021 | <0.001 | −0.0014 | <0.001 | 93 (69 to 116) | 0.87% | 0.81% (0.74 to 0.88) | 0.06% (0.01 to 0.11) | 1646 (886 to 12661) |

| Elective low-risk surgery | |||||||||

| Cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis | −0.0003 | 0.008 | −0.0001 | 0.425 | – | 0.43% | |||

| Inguinal or femoral hernia repair | −0.0019 | 0.009 | −0.0007 | 0.212 | – | 0.09% | |||

| Primary hip replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | −0.0020 | <0.001 | −0.0013 | <0.001 | 252 (227 to 278) | 0.17% | 0.13% (0.12 to 0.14) | 0.04% (0.03 to 0.05) | 2747 (2186 to 3701) |

| Primary knee replacement for arthrosis or arthritis | −0.0020 | <0.001 | −0.0016 | <0.001 | 228 (190 to 265) | 0.10% | 0.07% (0.07 to 0.08) | 0.02% (0.01 to 0.03) | 4729 (3513 to 7269) |

| Transurethral resection of prostate | −0.0003 | 0.130 | −0.0001 | 0.740 | – | 0.36% | |||

Logistic regression coefficients of hospital volume relate to an increment of 1 case per year.

VARL, value of acceptable risk limit,27 calculated from the logistic regression coefficient of the simple model. It estimates a minimum volume threshold to achieve a risk of inhospital mortality which is lower than a predefined acceptable risk. The acceptable risk for each treatment was set to the average mortality in the respective patient population during the observation period. The population impact number PIN is the reciprocal of the difference between the average mortality in the patient population and the adjusted mortality in those patients treated by hospitals with volumes above the threshold (population-based risk difference). It can be interpreted as average number of the entire patient population among whom one death is attributable to treatment by a below-threshold volume hospital. Covariates used for risk adjustment are displayed in the online supplementary table 3.

In total, 2.3 million patients treated for heart failure were studied. Risk-adjusted mortality was 8.5% (95% CI 8.4 to 8.6) in the very high volume quintile versus 9.2% (9.1 to 9.3) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). For volume as a continuous variable, no association was found after consideration of covariates (table 3).

During the observation period, 1.2 million patients were hospitalised for ischaemic stroke (table 1). Adjusted mortality in the very high volume quintile was 6.9% (95% CI 6.8 to 7.0) versus 7.3% (7.2 to 7.4) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). After consideration of covariates no measurable effect of hospital volume as a continuous variable was observed (table 3).

Among the 1.3 million patients treated for pneumonia (table 1), higher hospital volume was associated with higher inhospital mortality. Adjusted mortality was 11.5% (95% CI 11.3 to 11.6) in the very high volume quintile, 12.3% (12.2 to 12.5) in the medium volume quintile and 10.8% (10.7 to 10.9) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1), and the ORs were higher in the low to very high volume quintiles when compared with the very low volume quintile (table 2). When considered as a continuous variable, hospital volume was not associated with mortality (table 3).

For the more than 1.15 million patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, table 1), adjusted mortality was 3.1% (95% CI 3.0 to 3.2) in the very high volume quintile and 4.3% (4.2 to 4.4) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Hospital volume as a continuous variable had an independent effect on mortality (figure 2), and the minimum volume to achieve a lower-than-average risk of death was calculated as 271 patients per year. This threshold was estimated to prevent one death among 170 (158 to 185) COPD patients (table 3).

The analysis of 711 000 patients hospitalised for hip fracture (table 1) revealed slightly higher mortality in low to high volume quintiles when compared with the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Hospital volume as a continuous variable had no effect on mortality (table 3).

Elective heart and thoracic surgery

For each out of the four studied types of heart and thoracic surgery, lower inhospital mortality in association with higher hospital volume was observed.

From 2009 to 2014, about 52 600 patients were treated with isolated surgical aortic valve replacement (table 1). Adjusted mortality was 2.4% (95% CI 2.1 to 2.7) in the very high volume quintile versus 3.1% (2.8 to 3.4%)%) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Reduced odds of death were found in the medium to very high volume quintiles when compared with the very low volume quintile (table 2). As a continuous variable, hospital volume demonstrated an independent effect on mortality (figure 2). The minimum volume to achieve a lower-than-average risk of death was calculated as 147 annual treatments. This threshold resulted in a non-significant PRD of 0.2% (−0.02 to 0.3) and a PIN of 516 (288 to 2589, table 3).

Inhospital mortality of the 50 800 patients treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement (table 1) was 5.2% (95% CI 4.8 to 5.7) in the very high volume quintile versus 7.6% (7.1 to 8.2) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Hospital volume as a continuous variable revealed an independent effect on mortality (figure 2), and the minimum volume to fall below the average mortality of 6.6% was calculated as 157 cases per year. Application of this threshold was estimated to prevent one death among 133 (101 to 193) patients (table 3). This means that among 133 patients with transcatheter aortic valve replacement, one death would be prevented if all providing hospitals would perform this treatment at least 157 times per year.

A total of 184 000 patients were treated with an isolated coronary artery bypass graft (table 1). According to hospital quintiles, no constant association of volume and mortality was found (figure 1, table 2). However, an independent effect of hospital volume on mortality was observed when volume was analysed as a continuous variable (figure 2), and the minimum volume to achieve a risk of death below the average of 2.1% was calculated as 475 cases per year. This threshold led to a PIN of 658 (445 to 1271, table 3).

In total, 74 000 patients with partial lung resection for carcinoma were studied (table 1). In the very high volume quintile, adjusted mortality was 2.0% (95% CI 1.8 to 2.3) versus 3.8% (3.6 to 4.1) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). The observed independent effect of hospital volume when analysed continuously resulted in a minimum volume of 108 cases per year. This threshold was estimated to prevent one death among 168 (137 to 217) patients (table 3).

Elective major visceral surgery

Lower mortality associated with higher hospital volume was found for all six studied types of elective visceral surgery.

During the observation period, 331 000 colorectal resections for carcinoma were performed in German hospitals (table 1). Mortality was 5.2% (95% CI 5.0 to 5.4) in the very high volume quintile and 6.6% (6.4 to 6.8) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). In comparison to the very low volume quintile, odds of death were statistically significantly reduced in the medium to very high volume quintiles (table 2). Hospital volume as a continuous variable had an independent effect on mortality (figure 2). The minimum volume to achieve a risk of death below the average of 6.0% was calculated as 82 annual treatments, associated with a PIN of 197 (167 to 241, table 3).

A total of 179 000 colorectal resections were performed for diverticulosis (table 1). Adjusted mortality was 3.1% (95% CI 2.9 to 3.3) in the very high volume quintile versus 3.9% (3.8 to 4.1) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Hospital volume as a continuous variable had an independent effect on mortality, and a minimum volume of 44 was calculated to achieve a risk of death below the average of 3.5%. This threshold was associated with a PIN of 364 (269 to 564, table 3).

During the observation period, 68 000 patients with total nephrectomy for carcinoma were identified (table 1). In the very high volume quintile, adjusted mortality was 1.9% (95% CI 1.7 to 2.2) and in the very low volume quintile 2.3% (2.1 to 2.6). The independent effect of hospital volume as a continuous variable demonstrated borderline statistical significance (figure 2), and the minimum volume to achieve lower-than-average mortality was calculated as 40 cases per year. Application of this threshold would prevent one death among 459 (295 to 1056) nephrectomy patients (table 3).

Adjusted mortality among the 44 000 patients receiving cystectomy for carcinoma (table 1) was 4.0% (95% CI 3.6 to 4.4) in the very high volume quintile versus 5.5% (5.0 to 6.0) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Continuous increment of hospital volume was independently associated with lower mortality (figure 2). This relation of volume and outcome resulted in a minimum volume of 31 cases per year to fall below the average mortality of 4.7%. Application of this threshold was associated a PIN of 227 (150 to 480, table 3).

Among the 18 000 patients with complex oesophageal surgery for carcinoma, adjusted mortality was 5.8% (95% CI 5.1 to 6.6) in the very high volume quintile versus 10.5% (9.5 to 11.6) in the very low volume quintile. As a continuous variable, hospital volume had an independent effect on mortality, and the minimum volume to fall below the average mortality of 8.5% was calculated as 22 cases per year. If all hospitals would perform at least 22 complex oesophageal surgeries per year, one death among 47 (38 to 62) patients could be prevented (table 3).

A pancreatic resection for carcinoma was performed in 35 000 patients in total (table 1). Adjusted mortality was 6.4% (95% CI 5.8 to 7.0) in the very high volume quintile versus 11.7% (10.9 to 12.5) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Continuous increment of hospital volume was associated with lower mortality, and the minimum volume where risk of death would fall below the average mortality of 8.8% was calculated as 29 cases per year. This threshold resulted in a PIN of 46 (39 to 58, table 3).

Elective vascular surgery

In three out of the four studied types of elective vascular surgery, higher hospital volume was associated with lower inhospital mortality.

During the observation period, 247 000 patients were treated with surgical revascularisation of lower extremities for atherosclerosis (table 1). Risk-adjusted mortality was 2.8% (95% CI 2.7 to 3.0) in the very high volume quintile versus 3.3% (3.2 to 3.5) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Odds of death were reduced in all other quintiles when compared with the very low volume quintile (table 2). The association of volume and outcome persisted when volume was analysed as continuous variable (figure 2), and the minimum volume to achieve a mortality risk below the average of 3.0% was calculated as 123 cases per year. This led to the estimation that among 561 (387 to 1024) patients, one additional death was attributable to treatment by a hospital performing less than 123 of such operations (table 3).

In total, more than 22 000 patients receiving open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm were analysed (table 1). In the very high volume quintile, risk-adjusted mortality was 4.7% (95% CI 4.1 to 5.4) versus 7.8% (7.1 to 8.7) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). When analysed continuously, higher volume was independently associated with lower mortality (figure 2). The calculated minimum volume where risk would fall below the average of 6.0% was 18 cases per year. The resulting PIN was 104 (76 to 166, table 3).

Among the 42 000 patients treated with endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (table 1), risk-adjusted mortality was 1.6% (95% CI 1.3 to 1.9) in the very high volume quintile versus 1.7% (1.4 to 2.0) in the very low volume quintile. Highest mortality was observed in the medium volume quintile (2.1%, 1.8 to 2.4, figure 1). Odds of death were not significantly different between volume quintiles (table 2). Analysed as continuous variable, no statistically significant effect of hospital volume on mortality was observed (figure 2, table 3).

From 2009 to 2014, about 162 000 patients with carotid endarterectomy were identified (table 1). Risk-adjusted inhospital mortality was 0.75% (95% CI 0.66 to 0.86) in the very high volume quintile and 0.97% (0.87 to 1.07) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Continuous increment of hospital volume was independently associated with lower inhospital mortality (figure 2). A lower-than-average risk of mortality is expected if hospitals perform at least 93 carotid endarterectomies per year. Under this threshold, the estimated PIN was 1646 (886 to 12661, table 3).

Elective low-risk surgery

In three out of the five studied types of elective low-risk surgery, higher hospital volume was found to be associated with lower mortality when volume was categorised in quintiles. In two types of elective low-risk surgery, this relation persisted when volume was analysed as a continuous variable.

From 2009 to 2014, nearly 889 000 inpatient cholecystectomies for cholelithiasis were performed in German hospitals (table 1). Risk-adjusted mortality differed not significantly between volume quintiles (figure 1), as well as risk-adjusted odds of death (table 2). Continuous increment of hospital volume was not associated with mortality (table 3).

Among the 897 000 inpatient inguinal or femoral hernia repairs (table 1), mortality in the very high volume quintile was lower (0.07%, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.08) than in the very low volume quintile (0.10%, 0.09 to 0.12, figure 1). Yet, the independent effect of continuous increment of hospital volume was not statistically significant (table 3).

The analysis of more than 881 000 primary hip replacements for arthrosis or arthritis (table 1) revealed a constant association of hospital volume and mortality when patients were stratified by volume quintiles. Risk-adjusted inhospital mortality was 0.10% (95% CI 0.08 to 0.11) in the very high volume quintile versus 0.23% (0.21 to 0.25) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). In comparison to the very low volume quintile, odds of death were significantly reduced in all other volume quintiles (table 2). Within the analysis of continuous increment of hospital volume, an independent effect on mortality was observed (figure 2). A minimum volume of 252 cases per year was calculated to achieve a risk of mortality below the average of 0.17%. The PIN resulting from this threshold was 2747 (2186 to 3701, table 3).

Overall, 843 000 patients with primary knee replacement for arthrosis or arthritis were identified (table 1). Risk-adjusted mortality was 0.06% (95% CI 0.05 to 0.07) in the very high volume quintile versus 0.13% (0.11 to 0.14) in the very low volume quintile (figure 1). Continuous increment of hospital volume was independently associated with lower mortality (figure 2), and 228 annual cases were calculated as the minimum volume where risk of mortality would fall below the average of 0.10%. This minimum volume threshold resulted in an estimation of one preventable death among 4729 (3513 to 7269) primary knee replacement patients if all hospitals would perform at least 228 such operations per year (table 3).

In total, 434 000 patients with transurethral resection of prostate were studied (table 1). No statistically significant differences in inhospital mortality were found when patients were stratified by hospital volume quintiles (figure 1, table 2), and there was no significant association of hospital volume and mortality when volume was analysed continuously (table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

Within the sensitivity analysis, hospital volume was determined more widely by considering all those treatments or procedures, which could be regarded as technically similar to the specific treatment for which outcome was measured. The specific restrictions for the purpose of outcome measurement were applied after determining volume. Using this divergent volume definition, results remained substantially unchanged in 23 out of the 25 studied types of treatments.

Different findings were observed regarding isolated coronary artery bypass graft, where the relation of volume and mortality was more pronounced when all related procedures (ie, coronary bypass grafts in patients with acute myocardial infarction or combined with other heart surgery instead of elective isolated coronary operations only) were considered for determination of hospital volume. Different from the findings in the main analysis, higher volume was constantly associated with lower mortality when patients were stratified by these volume quintiles.

The volume–outcome association in colorectal resections for diverticulosis diminished when hospital volume was determined by considering all colorectal resections, regardless from medical indication. In contrast to the results of the main analysis, no statistically significant relation between volume and outcome was observed under this approach.

Discussion

Lower inhospital mortality in association with higher hospital volume was observed in 20 out of the 25 studied types of treatment when volume was categorised in quintiles and persisted in 17 types of treatment when volume was analysed as a continuous variable. While a volume–outcome relationship was not found in all studied emergency conditions and low-risk procedures, it was more consistently present regarding complex surgical procedures. The potential benefit of a centralisation according to the calculated minimum volume thresholds varied depending on the treatment-specific risk of death and the strength of the association between volume and mortality.

The analysis included every patient who underwent one of the studied types of inpatient treatment in a German acute care hospital during the observation period. Limitations occur from the limited information available in administrative data, including lack of information on appropriateness of patient selection for procedures. Although types of treatment and covariates for risk adjustment were defined in a sophisticated way, it is possible that unmeasured differences in disease severity, comorbidity or appropriateness may partly explain the association between volume and outcome. However, it should be considered that the more severe patients should intentionally not be treated by low-volume hospitals. Elective types of treatment were either defined by exclusion of patients with diagnoses pointing to an emergency admission or potential emergency diagnoses were considered within the risk adjustment models. However, this approach might not have fully separated elective admissions. The analyses could focus hospital volume only because physician volumes are not available in German administrative data. Regarding the determination of hospital volume, a possible misclassification of multicampus hospitals as high-volume providers must be taken into account, resulting in a possible underestimation of the association between hospital volume and mortality.30 Finally, this study did not consider hospital characteristics like teaching status, type of ownership or location.

Inpatient treatments for emergency conditions revealed mixed results. Associations between higher hospital volume and lower mortality were found for treatment of acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, ischaemic stroke and COPD. These results are similar to findings of previous studies from other countries.6 7 31–36 Regarding the treatment of patients with pneumonia, the analysis revealed higher mortality in hospitals with higher volumes. A similar finding has been reported by one previous US study,37 while another more recent US study found higher hospital volume being associated with lower mortality.6 No constant relation between volume and outcome was observed in hip fracture patients, similar to findings from a recent US study.38 However, a previous German study, which was based on national discharge data as well, but focused an earlier time period and surgically treated hip fracture patients only, found lower mortality related to higher hospital volumes.19 An Italian study observed a volume–outcome relation in hip fracture patients, too.36

An association of lower mortality and higher hospital volume was observed for each studied type of elective heart and thoracic surgery. These findings correspond to those from several European and US studies.3 5 14 36 39–41 In the present study, a more pronounced volume–outcome association was found for lung resection than for the studied types of heart surgery. This might be explained by an already quite high degree of centralisation of heart surgery services in Germany.

The analysis of major visceral surgery treatments revealed the most pronounced associations between volume and mortality, for example, regarding oesophageal surgery, cystectomy or pancreatic resection for carcinoma. These results are well supported by international evidence of a strong volume–outcome association in complex visceral surgery.3 11 12 17 18 42–46

In the case of vascular surgery, the analyses demonstrated lower mortality in association with higher hospital volume for lower extremity revascularisation, carotid endarterectomy and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm, in accordance to findings from the international literature.3 5 36 47 48 A volume–outcome relation for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (open, endovascular or totally percutaneous) had been demonstrated by a previous German study based on national discharge data.19 In the present study, however, endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm was analysed separately, and no significant relationship between volume and mortality was observed. This finding is in contrast to one study from the US,49 while a more recent US study found no significant association.50

Among the studied types of elective low-risk surgery, lower mortality associated with higher volume was found for primary knee and hip replacements, supported by international findings.8 51–54 However, no such relation was observed for cholecystectomy, similar to one study from England,55 but in contrast to studies from Italy and Scotland, which found a modest association between volume and outcome in cholecystectomy patients.10 36 The effect of volume on mortality observed in patients undergoing inguinal or femoral hernia repair was small. Studies from the USA and Sweden reported a volume–outcome relation for hernia repair but focused different outcomes (hernia recurrence or reoperation rates) and determined volume rather on the surgeon level.56 57 Regarding transurethral resection of prostate, no association between hospital volume and mortality was found. This confirms the findings of a Japanese study which found an association regarding complication and blood transfusion rates, but not regarding mortality.58

Overall, the results of the present study seem plausible in view of the current literature. Discrepancies to findings from other studies might be caused by differences in completeness of data or alternative methodological approaches, for example, regarding case definitions or volume determination. However, it is also possible that an association between volume and outcome is more or less existent in different countries, depending on characteristics of a healthcare system and hospital market structures.39

Minimum volume thresholds were calculated for those treatments, in which the association of volume and mortality persisted when volume was analysed as a continuous variable, which provides a strong indication that such an association truly exists. The highest population impact of centralisation according to the calculated thresholds was estimated for oesophageal surgery and pancreatic resection for carcinoma. Compared with this, the potential for improvement might appear small in the case of treatments with a basically low risk of mortality. However, one should consider that risk of mortality is likely correlated with the occurrence of non-lethal adverse events, in particular with regard to low-risk procedures. Thus, possible improvements of patient safety by centralisation might reach beyond effects on mortality.

When interpreting the findings of this study, one should note that observational studies cannot proof a causal volume–outcome relation. In consequence, this retrospective observational study cannot provide evidence that an application of the calculated thresholds as minimum volumes would actually improve quality of care. Therefore, the threshold values are meant to serve as basic orientation points for policy decisions in Germany and as hypothesis-generating landmarks for further research. Although estimated rather conservatively, roughly 80%–90% of hospitals providing a specific treatment performed annual volumes below the respective threshold and between 50% (acute myocardial infarction) and 70% (pancreatic resection for carcinoma) of patients were treated by those hospitals. Policy decisions on centralisation of services cannot rely on testing a statistical association on observational data, alone. As well, the regional availability and accessibility of inpatient services must be considered, in particular regarding emergency treatments. Centralisation should be pushed primarily in oversupplied geographical regions. However, experiences from the Netherlands have demonstrated that centralisation of inpatient services improved national outcome.59

A previous German study concluded that full implementation of the existing minimum volume regulation could improve the quality of hospital care in Germany.24 In addition to this, the present study identified further areas where centralisation could provide a benefit for patients and quantified the possible impact of centralisation efforts by using complete national hospital discharge data. These findings might support future policy decisions in Germany.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of Technische Universität Berlin.

Footnotes

Contributors: UN designed the study, conducted the analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. TM contributed to the study design, to the interpretation of data and to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Patient consent: This study is based on administrative data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1364–9. 10.1056/NEJM197912203012503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128–37. 10.1056/NEJMsa012337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg 2014;260:244–51. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Urbach DR, Baxter NN. Does it matter what a hospital is "high volume" for? Specificity of hospital volume-outcome associations for surgical procedures: analysis of administrative data. BMJ 2004;328:737–40. 10.1136/bmj.38030.642963.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gonzalez AA, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Understanding the volume-outcome effect in cardiovascular surgery: the role of failure to rescue. JAMA Surg 2014;149:119–23. 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ross JS, Normand SL, Wang Y, et al. Hospital volume and 30-day mortality for three common medical conditions. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1110–8. 10.1056/NEJMsa0907130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsugawa Y, Kumamaru H, Yasunaga H, et al. The association of hospital volume with mortality and costs of care for stroke in Japan. Med Care 2013;51:782–8. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829c8b70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, et al. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:1909–16. 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andresen K, Friis-Andersen H, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic repair of primary inguinal hernia performed in public hospitals or low-volume centers have increased risk of reoperation for recurrence. Surg Innov 2016;23:142–7. 10.1177/1553350615596636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrison EM, O'Neill S, Meurs TS, et al. Hospital volume and patient outcomes after cholecystectomy in Scotland: retrospective, national population based study. BMJ 2012;344:e3330. 10.1136/bmj.e3330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Wouters MW, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 2011;98:485–94. 10.1002/bjs.7413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Thrumurthy S, et al. Volume-outcome relationship in surgery for esophageal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis 2000-2011. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:1055–63. 10.1007/s11605-011-1731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holt PJ, Poloniecki JD, Loftus IM, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of the relationship between hospital volume and outcome following carotid endarterectomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007;33:645–51. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. von Meyenfeldt EM, Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, et al. The relationship between volume or surgeon specialty and outcome in the surgical treatment of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1170–8. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318257cc45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pieper D, Mathes T, Neugebauer E, et al. State of evidence on the relationship between high-volume hospitals and outcomes in surgery: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:e18:1015–25. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:511–20. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alsfasser G, Leicht H, Günster C, et al. Volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 2016;103:136–43. 10.1002/bjs.9958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krautz C, Nimptsch U, Weber GF, et al. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital morbidity and mortality following pancreatic surgery in Germany. Ann Surg 2017:1. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hentschker C, Mennicken R. The volume-outcome relationship and minimum volume standards—empirical evidence for Germany. Health Econ 2015;24:644–58. 10.1002/hec.3051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heller G, Günster C, Misselwitz B, et al. [Annual patient volume and survival of very low birth weight infants (VLBWs) in Germany—a nationwide analysis based on administrative data]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 2007;211:123–31. 10.1055/s-2007-960747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing; 2015. paris. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nimptsch U, Mansky T. [Disease-specific patterns of hospital care in Germany analyzed via the German Inpatient Quality Indicators (G-IQI)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2012;137 1449–57. 10.1055/s-0032-1305086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peschke D, Nimptsch U, Mansky T. Achieving minimum caseload requirements—an analysis of hospital discharge data from 2005-2011. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:556–63. 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nimptsch U, Peschke D, Mansky T. [Minimum Caseload requirements and In-hospital mortality: observational Study using Nationwide Hospital Discharge Data from 2006 to 2013]. Gesundheitswesen 2016 10.1055/s-0042-100731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pieper D, Eikermann M, Mathes T, et al. [Minimum thresholds under scrutiny]. Chirurg 2014;85:121–4. 10.1007/s00104-013-2644-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Research data centres of the Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the länder. Data supply | Diagnosis-Related Group Statistics. 2016. http://www.forschungsdatenzentrum.de/en/database/drg/index.asp (accessed 24 oct 2016).

- 27. Bender R. Quantitative Risk Assessment in Epidemiological Studies Investigating Threshold Effects. Biometrical Journal 1999;41:305–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bender R, Grouven U. Berechnung Von Konfidenzintervallen für die Population Impact Number (PIN). http://saswiki.org/images/7/7d/12.KSFE-2008-Bender-Konfidenzintervalle_f%C3%BCr_PIN.pdf.

- 29. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. . The REporting of studies conducted using observational Routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nimptsch U, Wengler A, Mansky T. [Continuity of hospital identifiers in hospital discharge data - Analysis of the nationwide German DRG Statistics from 2005 to 2013]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2016;117:38–44. 10.1016/j.zefq.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Han KT, Kim SJ, Kim W, et al. Associations of volume and other hospital characteristics on mortality within 30 days of acute myocardial infarction in South Korea. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009186. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. The association between hospital volume and processes, outcomes, and costs of care for congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:94–102. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, O'Donnell M, et al. Stroke Outcome Research Canada (SORCan) Working Group. Hospital volume and stroke outcome: does it matter? Neurology 2007;69:1142–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hall RE, Fang J, Hodwitz K, et al. Does the volume of ischemic stroke admissions relate to clinical outcomes in the Ontario Stroke System? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8(6 Suppl 3):S141–S147. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsai CL, Delclos GL, Camargo CA. Emergency department case volume and patient outcomes in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:656–63. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amato L, Colais P, Davoli M, et al. [Volume and health outcomes: evidence from systematic reviews and from evaluation of italian hospital data]. Epidemiol Prev 2013;37(2-3 Suppl 2):1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lindenauer PK, Behal R, Murray CK, et al. Volume, quality of care, and outcome in pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:262–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-4-200602210-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Metcalfe D, Salim A, Olufajo O, et al. Hospital case volume and outcomes for proximal femoral fractures in the USA: an observational study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010743 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gutacker N, Bloor K, Cookson R, et al. . Hospital surgical volumes and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting: using international comparisons to determine a safe threshold. Health Serv Res 2017;52:863–78. 10.1111/1475-6773.12508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Badheka AO, Patel NJ, Panaich SS, et al. Effect of hospital volume on outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:587–94. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel HJ, Herbert MA, Drake DH, et al. Aortic valve replacement: using a statewide cardiac surgical database identifies a procedural volume hinge point. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:1560–6. discussion 1565-6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Diamant MJ, Coward S, Buie WD, et al. Hospital volume and other risk factors for in-hospital mortality among diverticulitis patients: a nationwide analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;29:193–7. 10.1155/2015/964146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karanicolas PJ, Dubois L, Colquhoun PH, et al. The more the better?: the impact of surgeon and hospital volume on in-hospital mortality following colorectal resection. Ann Surg 2009;249:954–9. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a77bcd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu CJ, Chou YJ, Teng CJ, et al. Association of surgeon volume and hospital volume with the outcome of patients receiving definitive surgery for colorectal cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Cancer 2015;121:2782–90. 10.1002/cncr.29356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mayer EK, Purkayastha S, Athanasiou T, et al. Assessing the quality of the volume-outcome relationship in uro-oncology. BJU Int 2009;103:341–9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanchanale VS, Javlé P. Impact of hospital provider volume on outcome for radical urological cancer surgery in England. Urol Int 2010;85:11–15. 10.1159/000318631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Awopetu AI, Moxey P, Hinchliffe RJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between hospital volume and outcome for lower limb arterial surgery. Br J Surg 2010;97:797–803. 10.1002/bjs.7089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holt PJ, Poloniecki JD, Loftus IM, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of the relationship between hospital volume and outcome following carotid endarterectomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007;33:645–51. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dimick JB, Upchurch GR. Endovascular technology, hospital volume, andmortality with abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery.J Vasc Surg 2008;47:1150–4. 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McPhee JT, Robinson WP, Eslami MH, et al. Surgeon case volume, not institution case volume, is the primary determinant of in-hospital mortality after elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2011;53:591–9. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Critchley RJ, Baker PN, Deehan DJ. Does surgical volume affect outcome after primary and revision knee arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. Knee 2012;19:513–8. 10.1016/j.knee.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marlow NE, Barraclough B, Collier NA, et al. Centralization and the relationship between volume and outcome in knee arthroplasty procedures. ANZ J Surg 2010;80:234–41. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shervin N, Rubash HE, Katz JN. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;457:35–41. 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180375514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Soohoo NF, Farng E, Lieberman JR, et al. Factors that predict short-term complication rates after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2363–71. 10.1007/s11999-010-1354-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sinha S, Hofman D, Stoker DL, et al. Epidemiological study of provision of cholecystectomy in England from 2000 to 2009: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. Surg Endosc 2013;27:162–75. 10.1007/s00464-012-2415-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aquina CT, Kelly KN, Probst CP, et al. Surgeon volume plays a significant role in outcomes and cost following open incisional hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:100–10. 10.1007/s11605-014-2627-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nordin P, van der Linden W. Volume of procedures and risk of recurrence after repair of groin hernia: national register study. BMJ 2008;336:934–7. 10.1136/bmj.39525.514572.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sugihara T, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, et al. Impact of hospital volume and laser use on postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality in cases of benign prostate hyperplasia. J Urol 2011;185:2248–53. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. de Wilde RF, Besselink MG, Tweel vander I, et al. Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Impact of nationwide centralisation of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality. Br J Surg 2012;99:404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016184supp001.pdf (78.1KB, pdf)