Abstract

Evidence has shown that lymphatic drainage contributes to removal of debris from the brain but its role in the accumulation of amyloid β peptides (Aβ) has not been demonstrated. We examined the levels of various forms of Aβ in the brain, plasma and lymph nodes in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at different ages. Herein, we report on the novel finding that Aβ is present in the cervical and axillary lymph nodes of AD transgenic mice and that Aβ levels in lymph nodes increase over time, mirroring the increase of Aβ levels observed in the brain. Aβ levels in lymph nodes were significantly higher than in plasma. At age 15.5 months, there was a significant increase of monomeric soluble Aβ40 (p=0.003) and Aβ42 (p=0.05) in the lymph nodes over the baseline values measured at 6 months of age. In contrast, plasma levels of Aβ40 showed no significant changes (p=0.68) and plasma levels Aβ42 significantly dropped (p=0.02) at the same age. Aβ concentration was low to undetectable in splenic lymphoid tissue and several other control tissues including heart, lung, liver, kidneys and intestine of the same animals, strongly suggesting that Aβ peptides in lymph nodes are derived from the brain.

Introduction

Amyloid accumulation in senile plaques is the main neuropathological feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD); however, the mechanisms underlying its age-related accumulation remain elusive. Amyloid fibrils are composed of a 40–42 amino acid peptide called the amyloid beta protein (Aβ) (Glenner and Wong, 1984; Masters et al., 1985). Inadequate clearance of Aβ from the brain is considered to play an important role in amyloid accumulation (Neve and Robakis, 1998; Sambamurti et al., 2011). Prior research has demonstrated that peripheral lymph nodes participate in immune-surveillance and antigen presentation in the brain, particularly during neuro-inflammatory processes (Cserr et al., 1992; Hatterer et al., 2008); however, there is negligible information as to the potential participation of this system on Aβ clearance. Although the brain lacks lymphatic channels, circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and immune-competent cells such as dendritic and perivascular cells between brain (mainly perivascular spaces) and peripheral lymph nodes have been demonstrated (Boulton et al., 1996; Bradbury et al., 1981; Brinker et al., 1997; Cserr et al., 1992; Hatterer et al., 2008; Koh et al., 2005; Vega and Jonakait, 2004; Weller et al., 1998). It has been suggested that Aβ is present in the “interstitial cerebral fluid” (ICF) and that it might be drained into lymph nodes (Weller et al., 1998; Nedergaard, 2013). The route by which lymphatic drainage of Aβ may occur was suggested to be along basement membranes of cerebral capillaries and arteries (Carare, et al., 2013; Hawkes, et al., 2011). However, actual demonstration of Aβ in the lymph nodes has never, to our knowledge, been shown prior to our study. This may have been in part due to the arduous micro-dissection methods involved and to nuances of sample preparation for Aβ quantification.

For this investigation, we used a highly sensitive sandwich ELISA methodology (Asami-Odaka et al., 1995; Matsubara et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 1994) with various Aβ antibodies to test the hypothesis that Aβ is present in the lymph nodes and to relate its levels to those measured in the plasma and brain at different ages.

Methods

AD transgenic mice

We used Tg2576 transgenic mice. These mice express the 695-amino-acid isoform of human AβPP containing the double Lys670Asn, → Met 671→Leu mutation found in a Swedish family with early onset AD driven by a Syrian hamster Prnp promoter [Hsiao et al, 1996]. All animals were genotyped twice, at birth and after sacrifice, using a standard PCR protocol for genotyping as described (Hsiao et al., 1996). Mice in each experimental group were housed up to 4 to a cage in air-conditioned rooms at 22 °C with alternating twelve hours of light and darkness and fed ad libitum with AIN76A (Bethlehem, PA, USA). The Institutional Animal Review Board approved the use of mice for this study and national guidelines for humane treatment were followed.

Tissue Aβ measurement

Upon sacrifice, frontal cortex, lymph nodes and other organs (spleen, heart, lungs, intestine, liver) were dissected and homogenized for ELISA quantification as described (Scheuner et al., 1996). Dissection of murine lymph nodes required a methodical approach for their identification using a dissection microscope. Upon histological confirmation, surrounding fibrous tissue was removed. A schematic figure showing the lymph nodes selected for the study is shown in Figure 3. Soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were quantified in homogenates from fractions extracted with Tris-saline (TS) buffer (150mg/ml). As characterized previously (Asami-Odaka et al., 1995; Matsubara et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 1994), we used the 100,000 × g supernatants with the BNT77-BA27 or BNT77-BC05 antibodies for our ELISA tests to mainly quantify monomeric Aβ x-40 and x-42 species, respectively (Wako, Osaka, Japan). The obtained values were normalized to wet tissue weight. Microplates (Maxisorp White Microplate, Nunc, Rockilde, Denmark) were pre-coated with the antibodies for antigen capture (Takamura et al., 2011a; Takamura et al., 2011b), and sequentially incubated for 24 h at 4°C with 100 µl of the different samples followed by 24-hour with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated BA27 Fab’ fragment (anti- Aβ1–40, Wako, Osaka, Japan) or horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated BC05 Fab’ fragment (anti- Aβ35–43 for Aβ42, Wako, Osaka, Japan). The conjugate was detected by chemiluminescence using the SuperSignal ELISA Pico substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) on Veritas microplate Luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

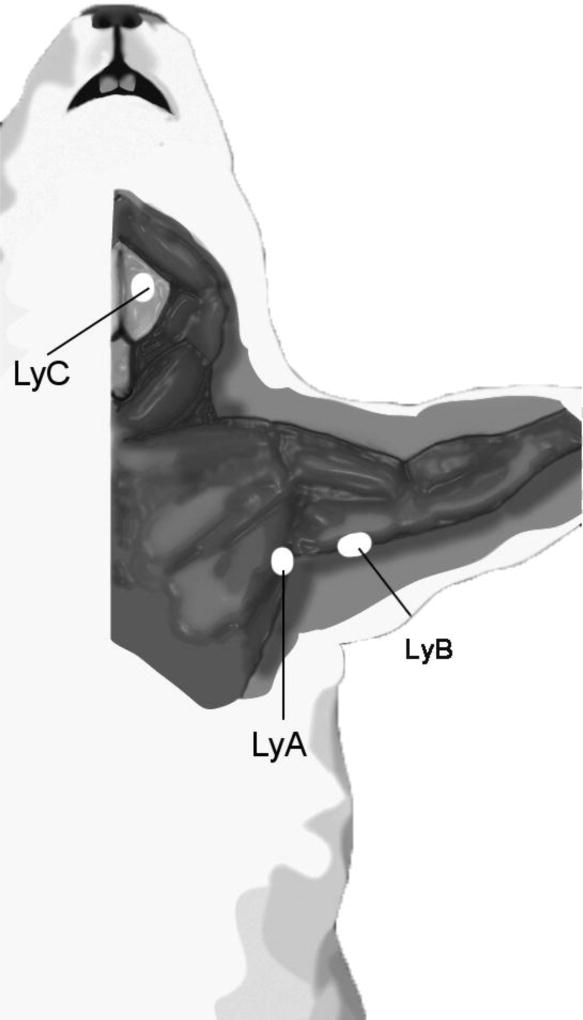

FIGURE 3. Schematic representation of the lymph node topographic anatomy in mice.

Superficial cervical lymph nodes (LyC) and axillary lymph nodes (LyA and LyB) were excised and analyzed as described in Methods. Since lymph nodes in mice are very minute, the two axillary lymph node subgroups (axillary proper and brachial component) from both limbs were combined to measure Aβ.

Statistical analysis

Where applicable, two-tailed student t-test was used for the comparison of groups with the statistical software (significance at <0.05) using GraphPad Prism version 3.00 for Windows, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). Sample size (n) is listed in the figures.

Results

Detection of Aβ in lymph nodes of Tg2576 mice

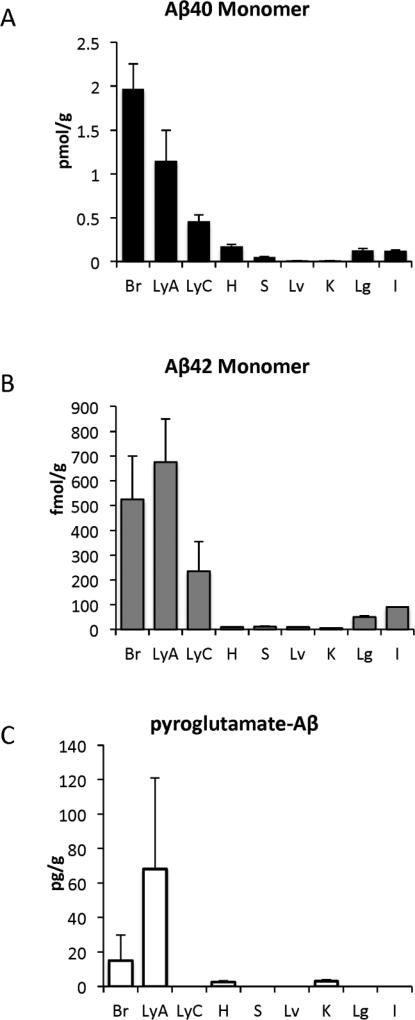

Levels of monomeric soluble Aβ40, Aβ42 and its pyroglutamate (N3pE) forms were quantified in brain, axillary lymph nodes, cervical lymph nodes and other somatic organs (including heart, spleen, liver, kidney lung and intestine) of Tg2576 transgenic mice at 12 months of age (Figure 1). Levels of monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 were high and readily detected in the brain and cervical and axillary lymph nodes and were either undetectable or at very low levels in the spleen and tested somatic tissues (Figure 1). N3pE- Aβ showed a different pattern in that its levels were substantially higher in axillary lymph nodes than in the brain and was very low or undetectable in other tested tissues, including cervical lymph nodes (Figure 1C). All forms of Aβ were low to undetectable in control lymphatic tissue from spleen suggesting that Aβ is not an intrinsic component produced in lymphatic tissue. Aβ levels were also low in peripheral organs such as the heart, liver, kidney, lung and intestine, strongly suggesting that the Aβ peptides found in the lymph nodes derived from the brain.

FIGURE 1. Determination of Aβ in the lymph node.

Levels of monomeric Aβ40 (A), Aβ42 (B), and N3pE-Aβ (C) were measured in extracts of brain (Br), axillary lymph node (LyA), cervical lymph node (LyC), heart (H), spleen (S), liver (Lv), kidney (K), lung (Lg) and Intestine (I) of Tg2576 mice at 12 months of age.

Time dependent change in Aβ levels in plasma and lymph nodes in Tg2576 mice

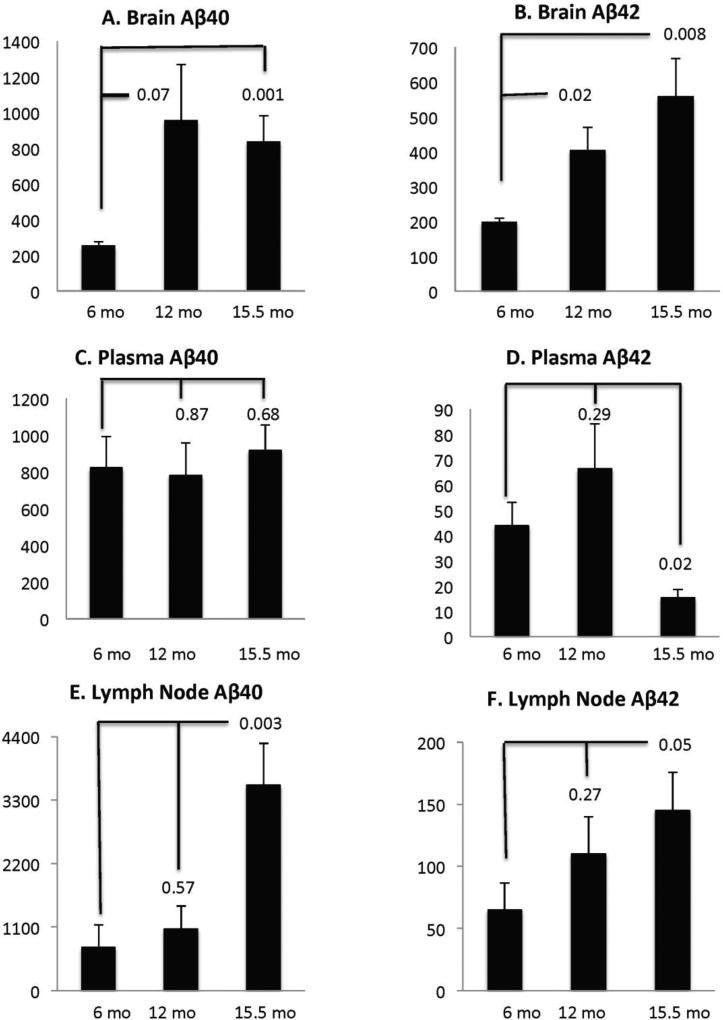

As widely reported (Hsiao et al, 1996), we observed a significant Aβ accumulation in the form of senile plaques in the brains of aged Tg2576 mice (data not shown). In addition, we observed a significant increase in saline soluble monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the aging brain of Tg2576 mice. The increase in Aβ40 appears to reach its peak at 12 mo (3.7 fold) and remains high at 15.5 mo (3.2 fold) but Aβ42 increased steadily with age, increasing two fold at 12 mo and 3 fold at 15.5 mo. However, variability in Aβ40 levels was higher and the 12-mo point only trended towards significance (p=0.07) while the 15.5 mo point was significant (P=0.02) (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

2A. Age induced changes in monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 in brain, plasma and axillary lymph nodes: Monomeric Aβ in Tg2576 mice measured by ELISA assays as described in Methods were plotted at 6, 12 and 15 months of age along with standard deviations. P values compared to the six-month baseline values are indicated above the appropriate graph. Tissue Aβ values were adjusted to fmol/g tissue and plasma Aβ are presented as fmol/ml. In comparison with 6-month-old mice, brain Aβ40 (A) and Aβ42 (B) levels increased significantly in 15-month-old mice (P<0.01). The increasing trends were also apparent at 12 mo with Aβ42 reaching significance (P=0.02). Axillary lymph nodes also show a parallel increase in both Aβ40 (E; p<0.003) and Aβ42 (F; P<0.05) at 15 mo, but changes, if any, were not significant at 12 mo. Samples of cervical lymph nodes were insufficient for measurement and will require analysis of pooled animals in future experiments. In the 15-month old mice, plasma Aβ40 did not show significant changes but Aβ42 levels dropped significantly (p=0.02).

Aβ42 was significant at both points with p values of 0.023 and 0.008 at 12 and 15.5 mo. The brain data therefore confirm all the trends seen in previous studies with this mouse model (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). To determine whether the content of monomeric Aβ in plasma and lymph node would change with age to reflect the raising levels of Aβ in the brain with age, Aβ levels were evaluated by ELISA. Using six month old brain values as baseline, we observed a significant increase of monomeric soluble Aβ40 (p=0.003) and Aβ42 (p=0.05) in the lymph nodes at 15.5 mo but did not find a significant change of either form at 12 mo. In contrast, plasma Aβ40 (p=0.68) showed no change and plasma Aβ42 significantly dropped (P=0.02) at 15.5 mo. Plasma Aβ at 6 and 12 months were not significantly different from each other. This reduction in plasma Aβ42 is consistent with other reports in literature (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001) (Figure 2).

Discussion

The molecular mechanism(s) responsible for amyloid accumulation in AD are poorly understood. An increase of amyloid production, a decrease of amyloid clearance or a combination of both may lead to abnormal amyloid accumulation in AD. Herein, we show for the first time that lymph nodes in a transgenic model of amyloidosis contain elevated levels of Aβ peptides, and that along with the blood brain barrier (BBB), they may be key players in the clearance of Aβ peptides from the brain. The levels of soluble monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 in lymph nodes closely mirrored the levels of the peptides over time in the brain. Pertaining to plasma Aβ levels, the results confirmed previous observations in Tg2576 mice; i.e., that Aβ40 levels do not change substantially and that Aβ42 levels decrease late in the process while Aβ levels continue to increase in the brain (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). A similar relationship was documented for Aβ levels in the CSF (Huang et al., 2012; Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Therefore, these studies support the widely prevalent view that brain is the sink for Aβ peptides. It has been alternatively proposed that the failure to observe an increase in Aβ in the plasma or in the CSF reflects a steady state level reached over time (Huang et al., 2012; Toledo et al., 2011). On the other hand, there were two interesting and contrasting findings pertaining to lymphatic Aβ. First was the observation that Aβ42 levels in plasma at 15 months of age decreased while Aβ40 and Aβ42 continued to increase in the lymph nodes (Figure 2). These observations suggest two possibilities; one is that the lymphatic system may be more efficient than the BBB as a mechanism for removal of Aβ from the brain. The other is that Aβ levels continue to increase over time as a consequence of Aβ accumulation within lymph nodes. Either possibility requires specific clearance experiments for confirmation, which are outside the scope of this initial report.

We do not have an explanation at this time regarding the finding of higher Aβ levels in axillary lymph nodes versus cervical lymph nodes or the presence of pyroglutamate Aβ only in axillary lymph nodes. Pyroglutamic acid is a lactam generated between the free amino terminal end and the cyclizes to form a lactam. The third residue of Aβ is a glutamate and a secondary cleavage that exposes this residue can form the pyroglutamate form (Mori et al., 1992). It is possible that Aβ is converted to the pyroglutamate containing form through secondary cleavage during lymphatic circulation and is therefore more prevalent in the distal lymph node rather than the proximal cervical nodes. Such unexpected observations, however, are not unique to this model. Albeit rare, metastases from primary brain tumors have been identified in axillary lymph nodes, but not in cervical lymph nodes, of some human tumor cases [http://mets.getthediagnosis.org/picture/11?sid=3233c38122c60955ff6406b93e8700a1. Accessed Jan 22, 2014]. This may underline a complex pattern of trafficking between the brain and lymph nodes.

The parenchyma of the CNS does not contain lymphatic channels. However, numerous investigations in rodents, primates and humans reveal the presence of lymphatic drainage from the brain into peripheral lymph nodes (for review, see (Koh et al., 2005)). Employing various tracers, flow from the ICF and perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces of the brain into lymph nodes has been elegantly demonstrated (Boulton et al., 1996; Brinker et al., 1997; Cserr et al., 1992; Vega and Jonakait, 2004). In addition to senile plaques, Aβ accumulation occurs also in a similar pattern (i.e., in the perivascular spaces and the ICF spaces) in AD (Weller et al., 1998). This pattern of accumulation has led some investigators to theorize that the lymphatic system may contribute to Aβ clearance (Iliff et al., 2012). Despite all of these prior investigations, the BBB has been studied as the primary route for Aβ clearance (Sagare et al; Ji et al., 2001; Shibata et al., 2000) without any reference to the role of the lymphatic system. To our knowledge, this study is the first to document the presence of Aβ in lymph nodes in support of such a mechanism of clearance. The other major study that examined tissue distribution of Aβ across tissues showed Aβ only in the brain although APP was present in multiple tissues (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001).

The potential participation of lymphatic Aβ clearance is further strengthened by additional recent studies reporting that murine PirB (paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B) and its human ortholog LilrB2 (leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2), present in human brain, are receptors for Aβ peptides (Kim et al., 2013). Interestingly, these receptors, which are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, are found in dendritic cells and include cell surface antigen receptors, co-receptors and co-stimulatory molecules of the immune system, molecules involved in antigen presentation to lymphocytes (Cella et al., 1997).

A caveat of this investigation is the possibility that Aβ is being produced in the lymph nodes. However, the fact that the Prnp promoter drives expression of the transgene in the CNS makes such possibility extremely unlikely [for discussion of this topic see Vidal et al (Vidal et al., 2009). In addition, neither the quantity of Aβ in the lymph nodes nor its time dependent increase (which parallels Aβ in the brain) were observed in splenic lymphoid tissue providing evidence against lymphatic origin of Aβ (Figure 1).

In conclusion, the study of the lymphatic system in AD and in during normal aging as it pertains to Aβ accumulation may provide important clues to the understanding of the pathogenesis of this disorder and to the development of new approaches for treatment and prevention. We propose that different biological insults that may lead to dysfunction of the lymphatic system (i.e., viral infections or viral reactivation or age related immune-dysfunction, among several others) may potentially play an indirect (and unrecognized) role in the amyloid accumulation that occurs in sporadic AD. We hope that these findings stimulate additional research to confirm the role and extent of participation of lymphatic tissue in Aβ clearance from the brain.

Research Highlights.

This is the first demonstration of Aβ in lymph nodes of an AD transgenic mouse model.

There was a time dependent increase in Aβ levels in lymph nodes, mirroring the increase of Aβ in the brain.

Higher levels of Aβ were detected in lymph nodes than plasma suggesting its closer proximity to brain Aβ.

Lymphatic clearance is an overlooked pathway for removal of Aβ and may play a role in AD pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH for grants AG046200; AG016783 and theAlzheimer’s Association for IIRG 10-173180.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asami-Odaka A, et al. Long amyloid beta-protein secreted from wild-type human neuroblastoma IMR-32 cells. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10272–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00032a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M, et al. Drainage of CSF through lymphatic pathways and arachnoid villi in sheep: measurement of 125I-albumin clearance. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1996;22:325–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1996.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury MW, et al. Drainage of cerebral interstitial fluid into deep cervical lymph of the rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:F329–36. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.240.4.F329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinker T, et al. Dynamic properties of lymphatic pathways for the absorption of cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:493–8. doi: 10.1007/s004010050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare RO, et al. Review: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, prion angiopathy, CADASIL and the spectrum of protein elimination failure angiopathies (PEFA) in neurodegenerative disease with a focus on therapy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:593–611. doi: 10.1111/nan.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M, et al. A novel inhibitory receptor (ILT3) expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells involved in antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1743–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr HF, et al. Drainage of brain extracellular fluid into blood and deep cervical lymph and its immunological significance. Brain Pathol. 1992;2:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1992.tb00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:1131–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatterer E, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid dendritic cells infiltrate the brain parenchyma and target the cervical lymph nodes under neuroinflammatory conditions. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CA, et al. Perivascular drainage of solutes is impaired in the mouse brain and in the presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;121:431–443. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, et al. beta-Amyloid Dynamics in Human Plasma. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1591–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, et al. Amyloid beta40/42 clearance across the blood-brain barrier following intra-ventricular injections in wild-type, apoE knock-out and human apoE3 or E4 expressing transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:23–30. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, et al. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, et al. Human LilrB2 is a beta-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer's model. Science. 2013;341:1399–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1242077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh L, et al. Integration of the subarachnoid space and lymphatics: is it time to embrace a new concept of cerebrospinal fluid absorption? Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4245–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara E, et al. Lipoprotein-free amyloidogenic peptides in plasma are elevated in patients with sporadic Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori H, et al. Mass spectrometry of purified amyloid beta protein in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17082–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RL, Robakis NK. Alzheimer's disease: a re-examination of the amyloid hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:15–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M. Neuroscience. Garbage truck of the brain. Science. 2013;28:1529–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1240514. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagare AP, et al. Neurovascular dysfunction and faulty amyloid beta-peptide clearance in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambamurti K, et al. Targets for AD treatment: conflicting messages from gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Neurochem. 2011;117:359–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–70. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, et al. Clearance of Alzheimer's amyloid-ss(1–40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1489–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, et al. An increased percentage of long amyloid beta protein secreted by familial amyloid beta protein precursor (beta APP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264:1336–40. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A, et al. Dissociation of beta-amyloid from lipoprotein in cerebrospinal fluid from Alzheimer's disease accelerates beta-amyloid-42 assembly. J Neurosci Res. 2011a;89:815–21. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A, et al. Extracellular and intraneuronal HMW-AbetaOs represent a molecular basis of memory loss in Alzheimer's disease model mouse. Mol Neurodegener. 2011b;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo JB, et al. Factors affecting Abeta plasma levels and their utility as biomarkers in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:401–13. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0861-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega JL, Jonakait GM. The cervical lymph nodes drain antigens administered into the spinal subarachnoid space of the rat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:416–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and parenchymal amyloid deposition in transgenic mice expressing the Danish mutant form of human BRI2. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller RO, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: amyloid beta accumulates in putative interstitial fluid drainage pathways in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:725–33. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65616-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]