Abstract

Back pain is a major contributor to disability and has significant socioeconomic impacts worldwide. The degenerative intervertebral disc (IVD) has been hypothesized to contribute to back pain, but a better understanding of the interactions between the degenerative IVD and nociceptive neurons innervating the disc and treatment strategies that directly target these interactions is needed to improve our understanding and treatment of back pain. We investigated degenerative IVD-induced changes to dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron activity and utilized CRISPR epigenome editing as a neuromodulation strategy. By exposing DRG neurons to degenerative IVD-conditioned media under both normal and pathological IVD pH levels, we demonstrate that degenerative IVDs trigger interleukin (IL)-6-induced increases in neuron activity to thermal stimuli, which is directly mediated by AKAP and enhanced by acidic pH. Utilizing this novel information on AKAP-mediated increases in nociceptive neuron activity, we developed lentiviral CRISPR epigenome editing vectors that modulate endogenous expression of AKAP150 by targeted promoter histone methylation. When delivered to DRG neurons, these epigenome-modifying vectors abolished degenerative IVD-induced DRG-elevated neuron activity while preserving non-pathologic neuron activity. This work elucidates the potential for CRISPR epigenome editing as a targeted gene-based pain neuromodulation strategy.

Keywords: back pain, epigenome editing, disc degeneration

Nociceptive neuron sensitization has been suggested as a primary mediator of discogenic back pain. In this issue of Molecular Therapy, Stover et al. demonstrate the synergistic role between IL-6/pH to drive neuron sensitization by human degenerative IVD and a novel gene-based neuromodulation strategy to regulate/treat this sensitization using CRISPR epigenome editing.

Introduction

Low back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide,1 ranks third in disease burden according to disease-adjusted life-years,2 and generates a tremendous socio-economic cost.3 Numerous factors have been associated with back pain, including degenerative disc disease, which is characterized by the breakdown of the intervertebral disc (IVD) extracellular matrix (ECM),4, 5 a loss of disc height,6 an inflammatory response,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and altered innervation of the IVD.14, 15, 16 Despite the observation of these changes in the degenerative IVD and hypotheses on the relationship of these changes to painful symptoms,17, 18, 19, 20 the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood, and treatment strategies are limited. Here, we develop a model to demonstrate the underlying sensitizing interactions between the degenerative disc and peripheral neurons, and use that model to demonstrate targeted CRISPR epigenome editing to modulate these degenerative IVD-induced sensitivities.

In the healthy IVD, neurons that originate in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) innervate the outer lamellae of the IVD. The majority of these neurons are nociceptive neurons expressing calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and TRPV1.13, 22, 23, 24 In degenerative IVDs, the number of nociceptive neurons innervating the disc increases26 and nociceptive neurons expressing CGRP24, 27 extend into typically aneural regions of the inner annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP).14, 15, 16, 24, 27, 28 Nociceptive neurons innervating the degenerative IVD are exposed to pathologically high levels of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-1β7, 8, 10, 29, 30 and to pathologically low pH levels.31 TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 have been demonstrated to sensitize nociceptive neurons to thermal stimuli32, 33, 34 and induce thermal hyperalgesia32, 35, 36, 37 in models of peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, acidic pH (6.0–7.0) lowers the temperature threshold of TRPV1 and potentiates signaling through TRPV1.38 As a result, the presence of multiple sensitizing factors in the degenerative IVD may trigger discogenic pain by sensitizing TRPV1 to stimuli that are non-painful in healthy patients. We develop an in vitro model to investigate these interactions and test CRISPR epigenome editing strategies in peripheral neurons to regulate these interactions.

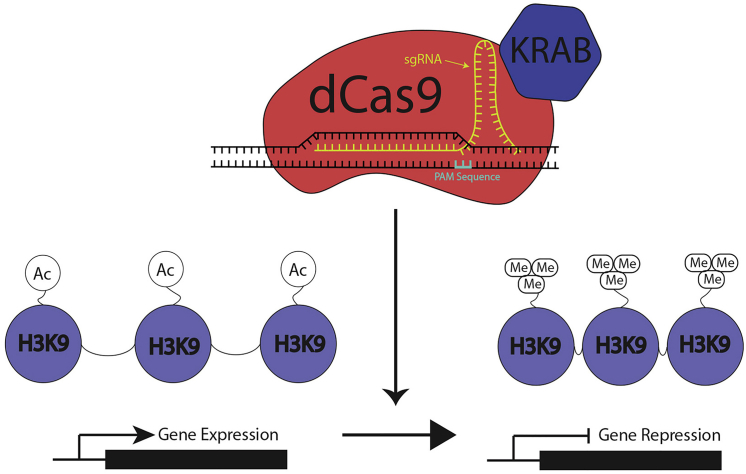

CRISPR-based epigenome editing allows for stable, highly site-specific39 histone modifications to modulate gene expression. In brief, CRISPR-Cas9-based epigenome editing utilizes a nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) and a synthetic guide RNA to target specific DNA sequences40, 41, 42 (Figure 1). The fusion of Kruppel associated box domain (KRAB) to dCas9 produces highly targeted H3K9 histone methylation,43, 44, 45, 46 which can be used to suppress endogenous gene expression. Here, we propose direct regulation of peripheral neuron activity via CRISPR epigenome editing to treat discogenic back pain symptoms. Using this technique, back pain may be treated by epigenome modifications of pain-related genes in nociceptive neurons innervating the IVD.

Figure 1.

CRISPR-Based Epigenome Editing for the Regulation of Gene Expression

CRISPR-based epigenome editing requires the use of small guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that direct a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused with KRAB to a targeted genomic location. Targeting of KRAB to these specific genomic locations (endogenous promoters and enhancer elements) results in targeted H3K9 tri-methylation, which produces heterochromatin DNA and subsequent gene repression.

The objective of the present study was to develop a model to test the hypothesis that degenerative IVD conditions (i.e., inflammatory cytokines produced by human degenerative IVD and acidic pH) can induce elevated activity of nociceptive neurons to noxious stimuli, elucidate the factors regulating these changes, and demonstrate CRISPR epigenome editing of nociceptive neurons as a potential discogenic back pain treatment by regulating the peripheral neuron response to these deleterious interactions. This work elucidates the synergistic effects of low pH and the IL-6/AKAP150 pathway as a primary pathway for degenerative IVD neuron sensitization and demonstrates epigenome regulation of this pathway as a pain-modulation strategy.

Results

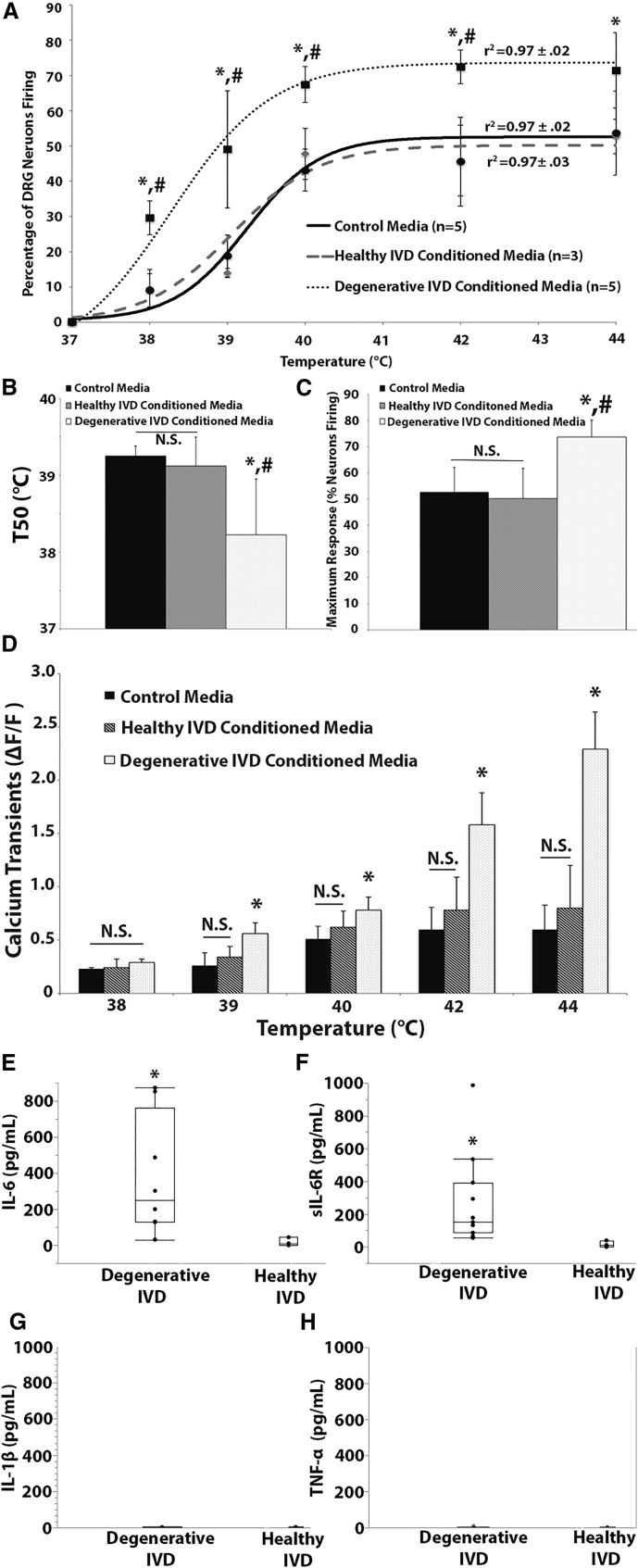

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Triggers Elevated DRG Neuron Activity to Thermal Stimuli

We measured neuronal calcium activity in cultured DRG neurons exposed to thermal stimulation.47, 48 The percentage of DRG neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients (Figure 2) in the degenerative IVD conditioned media group was significantly elevated compared with the control media (p < 0.05) and healthy IVD conditioned media groups (p < 0.05) at temperatures as low as 38°C (Figure 3A). In addition, the percentages of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients in the healthy IVD conditioned media groups were similar to the percentages of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients in the control media group at all temperatures tested (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the maximum calcium transient of conditioned media group neurons was significantly elevated over control (p < 0.05) and healthy IVD conditioned media groups (p < 0.05) at temperatures as low as 39°C (Figure 3D).

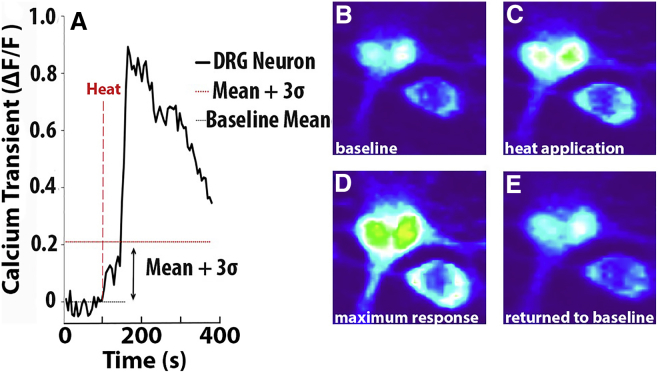

Figure 2.

Imaging of Calcium Transients in DRG Neurons

(A) A representative calcium signal (ΔF/F) for a neuron exhibiting a calcium transient in response to thermal stimuli. DRG neurons were considered to have calcium transients when the ΔF/F for the neuron exceeded the threshold level defined as the mean ΔF/F value at baseline plus 3 SDs. (B–E) Calcium images of representative DRG neurons at baseline (B), immediately following thermal stimulation (C), at maximum response to thermal stimuli (D), and return to baseline following stimuli (E).

Figure 3.

Degenerative IVDs Trigger Increased Heat-Evoked Neuron Activity in Peripheral Neurons

(A) The percentage of rat DRG neurons exhibiting calcium transients in response to thermal stimuli as a function of temperature was fitted to a Boltzmann curve for the degenerative IVD conditioned media (n = 5 patients), healthy IVD conditioned media (n = 3) patients, and control media groups. (B and C) The T50 (B) and Tmax (C) generated from dose-response curve fitting for the degenerative IVD conditioned media, healthy IVD conditioned media, and control media groups. (D) The maximum calcium transients of rat DRG neurons exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of degenerative IVD conditioned media, healthy IVD conditioned media, and control media. (E–H) Levels of IL-6 (E), sIL-6R (F), IL-1β (G), and TNF-α (H) in healthy and degenerative IVD conditioned media. (A–D) *p < 0.05 when compared with the control media group for the same temperature. (A–C) #p < 0.05 when compared with the healthy IVD conditioned media group for the same temperature. (E–H) *p < 0.05 when compared with healthy IVD conditioned media. Error bars are SD.

The percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients as a function of temperature was well defined by curve fitting the data to the Boltzmann equation for the control media (r2 = 0.97 ± 0.02), healthy IVD conditioned media (r2 = 0.97 ± 0.03), and degenerative IVD conditioned media (r2 = 0.97 ± 0.02) treatment groups (Figure 3A). The T50, the temperature at which half the maximum heat-induced calcium response (Tmax) occurs, and the Tmax was calculated via Boltzmann equation fits to each trial. The T50 value of neurons exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of degenerative IVD conditioned media (38.25°C ± 0.77°C) was significantly lower than the T50 values in both the control media (39.25°C ± 0.13°C; p < 0.05) and the healthy IVD conditioned media treatment groups (39.12°C ± 0.38°C; p < 0.05) (Figure 3B). In addition, the Tmax of neurons exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of degenerative IVD conditioned media (73.69% ± 6.5%) was significantly greater than the maximum response in the control media (52.69% ± 9.42%; p < 0.05) and healthy IVD conditioned media groups (51.25% ± 11.58%; p < 0.05) (Figure 3C).

IL-6 Is the Primary Mediator of DRG Neuron Activation Induced by Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media

Degenerative IVD conditioned media exhibited significantly elevated levels of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) (Figures 3E and 3F), but not IL-1β (Figure 3G) or TNF-α (Figure 3H), when compared with healthy IVD conditioned media, indicating degenerative IVD-induced elevated neuron activity is potentially mediated through an IL-6 signaling pathway. To test this hypothesis, the original sensitization experiments were repeated and confirmed as the percentage of rat DRG neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients in the presence of degenerative IVD conditioned media and the maximum calcium transients were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) when compared with the control media group at temperatures as low as 38°C (Figures 4A and 4B). When rat DRG neurons were exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with IL-6 blocking antibody, the percentage of neurons experiencing heat-induced calcium transients and their maximum calcium transient returned to control media levels (p = 1.0) for all temperatures tested (Figures 4A and 4B) and was significantly less (p < 0.05) than the percentage of neurons experiencing heat-induced calcium transients and the maximum calcium transient in the degenerative IVD conditioned media group at all temperatures above 38°C (Figures 4A and 4B). In contrast, addition of the isotype control antibody had no effect on heat-induced calcium transients (p = 0.895) and the maximum calcium transients (Figures 4A and 4B). Furthermore, the IL-6-induced increased neuron activity was seen in DRG neurons exposed to conditioned media from each patient, because all degenerative IVD conditioned media groups showed a decrease (p < 0.05) of heat-induced calcium response after IL-6 blocking antibody exposure (Figures 4B and 4E).

Figure 4.

IL-6 Is the Primary Mediator of Increased Peripheral Neuron Activity in the Degenerative IVD

(A) The maximum calcium transients of rat DRG neurons subjected to thermal stimuli in the presence of control media, conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody (20 μg/mL), conditioned media, and conditioned media plus isotype control antibody group (20 μg/mL). (B) The mean Boltzmann curve fittings of the percentage of neurons exhibiting calcium transients as a function of temperature for the control media, conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody, conditioned media, and conditioned media plus isotype control antibody groups. (C and D) The Tmax (C) and T50 (D) generated from dose-response curve fitting for the control media, conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody (20 μg/mL), conditioned media plus isotype control antibody (20 μg/mL), and conditioned media groups (n = 5). (E) Percentage of DRG neurons firing in response to temperatures of 39°C and 44°C when exposed to conditioned media or conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody. (A–D) Values are mean ± SDs. *p < 0.05 compared with the control media group at the same temperature; #p < 0.05 compared with the conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody group at the same temperature. (E) Values are percentage of neurons exhibiting calcium transients in response to thermal stimuli. *p < 0.05 compared with the conditioned media plus IL-6 antibody group for the same patient at the same temperature. Error bars are SD.

The number of neurons demonstrating heat-induced calcium transients as a function of temperature was well defined by curve fitting the data to the Boltzmann equation for the control media (r2 = 0.97 ± 0.02), degenerative IVD conditioned media (r2 = 0.97 ± 0.02), IL-6 blocking antibody (r2 = 0.98 ± 0.02), and isotype control antibody (r2 = 0.94 ± 0.04) treatment groups (Figure 4B). The T50 and Tmax were calculated via Boltzmann equation fits to each trial. The T50 value of neurons exposed to heat stimuli in the presence of conditioned media supplemented with IL-6 blocking antibody (39.53°C ± 0.4°C) returned to control media levels (39.25°C ± 0.13°C; p = 0.993) and was significantly greater than the T50 values of neurons in both the conditioned media (38.25°C ± 0.77°C; p = 0.004) and isotype control antibody groups (38.16°C ± 0.4°C; p = 0.003) (Figure 4C). In addition, the Tmax of DRG neurons exposed to heat stimuli in the presence of conditioned media supplemented with IL-6 blocking antibody (44.6% ± 11%) returned to control media levels (52.7% ± 9.4%; p = 0.534) and is significantly less than the maximum response of neurons in the conditioned media (73.7% ± 6.5%; p < 0.0001) and isotype control antibody groups (66% ± 2.8%; p = 0.001) (Figure 4D).

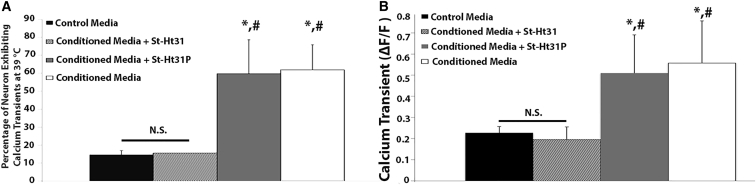

Inhibition of AKAP Abolishes IL-6-Mediated Increased DRG Neuron Activity by Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media

Elevated neuron activity induced by degenerative IVD conditioned media was once again confirmed because the percentage of DRG neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients (59.72% ± 18.9%) and the maximum calcium transient [0.57 ± 0.19 (ΔF/F)] at 39°C exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media were significantly greater (p < 0.05) than the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients (14.36% ± 2.3%; Figure 5B) and the maximum calcium transients in the control group [0.23 ± 0.04 (ΔF/F); Figure 5A]. When neurons were exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media in the presence of the AKAP inhibitor St-Ht31, the heat-induced calcium response returned to baseline levels (Tmax: 15.51% ± 2.7%, max calcium transient: 0.19 ± 0.04 ΔF/F) and was not significantly different from the control media group (p = 0.998; Figures 5A and 5B). In addition, the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients and the maximum calcium transient in the degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with the control peptide St-Ht31P [Tmax: 61.91% ± 13.9%, maximum calcium transient: 0.52 ± 0.18 (ΔF/F)] were significantly greater than the control media and the St-Ht31 groups (p < 0.05), but not significantly different from the degenerative IVD conditioned media group (Figures 5A and 5B).

Figure 5.

AKAP Mediates Thermal Stimuli-Induced Increased Activity of DRG Neurons in the Degenerative IVD

(A) Percentage of rat DRG neurons exhibiting calcium transients in response to thermal stimuli at 39°C in the presence of control media, degenerative IVD conditioned media, degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with the AKAP inhibitor peptide St-Ht31 (50 μM), or degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with the control peptide St-Ht31P (50 μM). n = 3 for all groups tested. (B) The maximum calcium transients of rat DRG neurons exposed to thermal stimuli at 39°C in the presence of control media, degenerative IVD conditioned media, degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with the AKAP inhibitor peptide St-Ht31 (50 μM), or degenerative IVD conditioned media supplemented with the control peptide St-Ht31P (50 μM). *p < 0.05 compared with the control media group; #p < 0.05 when compared with the degenerative IVD conditioned media plus St-Ht31P group. Error bars are SD.

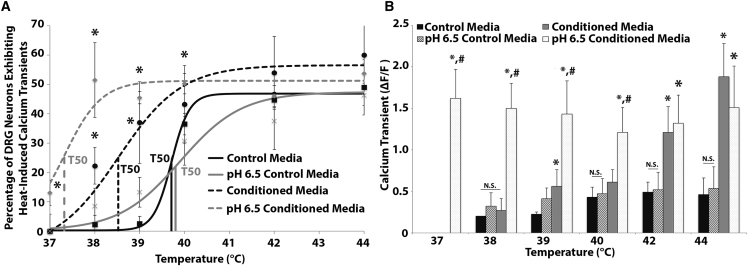

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media and Pathological Acidic pH Levels Synergistically Enhance Rat DRG Neuron Activity to Heat Stimuli and Trigger Spontaneous Neuron Activity

The percentage of rat DRG neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients when exposed to pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media was significantly elevated (p < 0.05) over all other media conditions tested at 37°C, 38°C, and 39°C (Figure 6A). At 37°C, spontaneous calcium transients were observed in neurons in the pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media group (13% ± 4.2%; Figure 6A), which had not been observed in any other experiment or group tested.

Figure 6.

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media and Acidic pH Synergistically Enhance Sensory Neuron Activity to Thermal Stimuli and Trigger Spontaneous Firing

(A) The percentage of rat DRG neurons exhibiting calcium transients when exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of control media (pH 7.4 or pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media) (n = 4). (B) The maximum calcium transient of rat DRG neurons exposed to thermal stimuli in the presence of control media (pH 7.4 or pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media) (n = 4). *p < 0.05 when compared with the control media group, #p < 0.05 when comparing pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media group with pH 7.4 degenerative IVD conditioned media group. Error bars are SD.

The T50 values of neurons in the pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media group (37.32°C ± 0.39°C; p = 0.02; Figure 6A) were significantly decreased compared with the degenerative IVD conditioned media (38.48°C ± 0.28°C), the pH 6.5 control media (39.76°C ± 0.76°C; p = 0.01), and the control media (39.62°C ± 0.24°C; p = 0.02) groups (Figure 6A). Furthermore, the maximum calcium transients of the pH 6.5 degenerative IVD conditioned media group were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) over all other media conditions tested at 37°C to 40°C (Figure 6B).

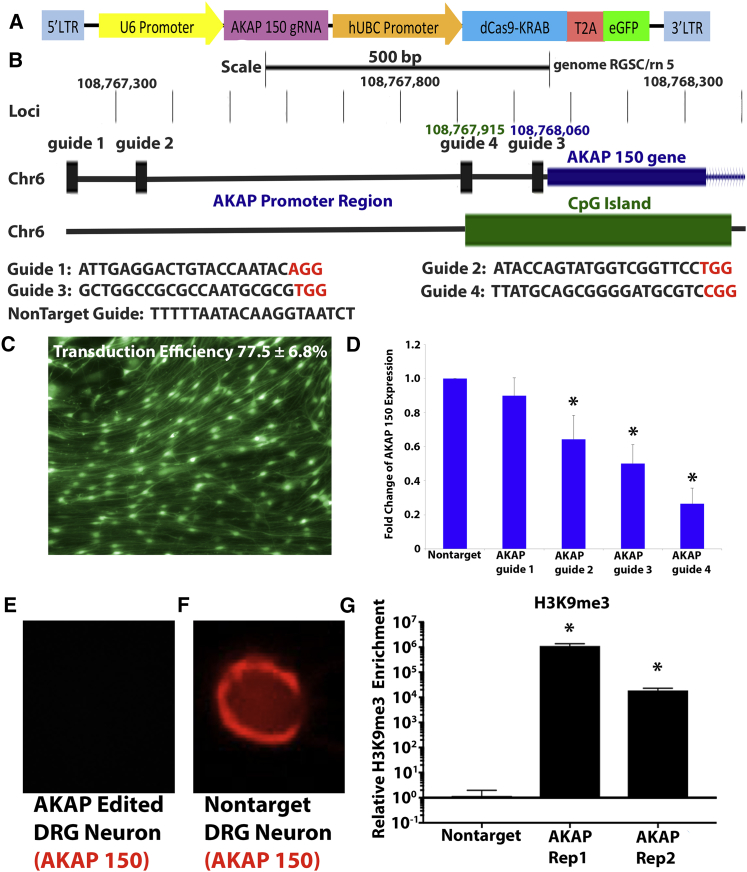

Epigenome Editing of AKAP150 Promoter in Rat DRG Neurons Abolishes Degenerative IVD-Induced Increases in DRG Neuron Activity

We designed four guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the endogenous promoter of AKAP150 to direct dCas9-fused KRAB to specific loci within the promoter via lentiviral vector. Robust transduction of rat DRG neurons and epigenome editing system expression was observed (transduction efficiency 77.5% ± 6.8%, n = 5; Figure 7C). Transduction of DRG neurons with CRISPR epigenome editing lentiviral vectors targeting AKAP150 regulated expression of AKAP150 at both the RNA (Figure 7D) and the protein levels (Figures 7E and 7F), with AKAP guide 4 exhibiting maximum downregulation when compared with DRG neurons transduced with non-target lentiviral vectors (26.1% ± 9.2% of non-target RNA expression; p < 0.05). In addition, CRISPR epigenome editing vectors targeting AKAP150 produced significantly elevated H3K9me3 localized to the gRNA binding site in the AKAP150 promoter (Figure 7G) when compared with non-target. Furthermore, the expression of adjacent genes was not affected by AKAP150 epigenome editing (Figure S1). Together, these results demonstrate the ability to regulate AKAP150 gene expression in DRG neurons via highly localized and site-specific epigenome editing. The most effective gRNAs were the closest in proximity to an identified CpG island in the promoter, with decreasing efficacy as the gRNA increased in distance from this CpG island (Figure 7B). Next, we investigated the ability of AKAP150 epigenome editing to regulate DRG neuron activity in degenerative IVD conditions.

Figure 7.

Epigenome Editing of DRG Neurons Regulates AKAP150 Gene Expression in Vitro

(A) Vector map of CRISPR epigenome editing vectors targeting the AKAP150 gene. (B) Schematic of the promoter region of the AKAP150 gene showing positions of the AKAP150 gene (blue), the CpG island (green), and the position and sequence of the small guide RNAs (sgRNAs) (black; PAM in red). (C) DRG neurons transduced (efficiency 77.5% ± 6.8%, n = 5) with AKAP150 epigenome editing vectors expressing GFP. (D) Epigenome editing of AKAP150 expression in rat DRG neurons. *p < 0.05 compared with non-target. (E and F) AKAP150 protein expression (red) in AKAP150 epigenome edited (E) and non-target epigenome edited (F) DRG neuron. (G) H3K9me3 of the AKAP150 promoter in AKAP150 epigenome editing and non-target epigenome edited DRG neurons. *p < 0.05 compared with non-target. Error bars are SD.

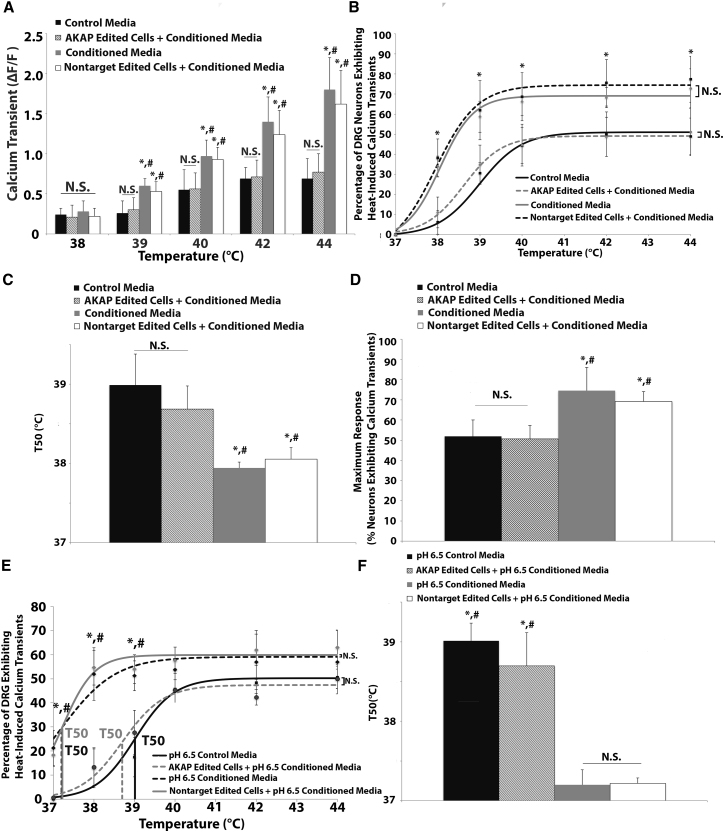

Both the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients and their maximum calcium transient were elevated in naive (non-transduced) neurons and neurons receiving non-targeting lentiviral vectors after exposure to degenerative IVD conditioned media compared with the control media group (p < 0.05). However, when AKAP150 epigenome edited neurons were exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media, the percentage of neurons demonstrating heat-induced calcium transients and the maximum calcium transient were not significantly different from control media levels (Figures 8A and 8B). From the curve fitting, the T50 value of AKAP150 epigenome edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media (38.7°C ± 0.29°C) was significantly higher than the T50 value of naive (37.94°C ± 0.07°C; p = 0.003) and non-target epigenome edited neurons (37.8°C ± 0.29°C; p = 0.01), yet not significantly different from the control media group (38.99°C ± 0.39°C; p = 0.3298) (Figure 8C). The Tmax of AKAP150 epigenome edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media (50.63% ± 6.59%) returned to control levels (51.12% ± 8.02%; p = 0.9959) and was significantly decreased compared with the Tmax of naive (74.48% ± 11.06%; p = 0.001) and non-target epigenome edited neurons (69.14% ± 4.93%; p = 0.001) exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Epigenomic Editing of AKAP150 Expression in DRG Neurons Abolishes Degenerative IVD-Induced Neuron Sensitization to Thermal Stimuli

(A) The maximum calcium transient of naive neurons exposed to control media and naive cells, AKAP epigenome edited cells, and non-target epigenomically edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media. *p < 0.05 compared with control media group, #p < 0.05 compared with AKAP edited neuron group. (B) The mean Boltzmann fit curves of percentage of neurons exhibiting calcium transients to thermal stimuli as a function of temperature for naive neurons exposed to control media and naive cells, AKAP epigenome edited cells, and non-target epigenomically edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media. *p < 0.05 compared with control media group. (C and D) The T50 (C) and Tmax (D) generated from the dose-response curve from naive neurons exposed to control media and naive cells, AKAP epigenome edited cells, and non-target epigenomically edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD conditioned media. *p < 0.05 compared with control media; #p < 0.05 compared with non-target cells exposed to conditioned media. (E) The mean Boltzmann fit curves of percentage of neurons exhibiting calcium transients to thermal stimuli as a function of temperature for naive neurons exposed to pH 6.5 control media and naive cells, AKAP epigenome edited cells, and non-target epigenomically edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD pH 6.5 conditioned media. *p < 0.05 compared with pH 6.5 control media group. (F) The T50 generated from the dose-response curve from naive neurons exposed to pH 6.5 control media and naive cells, AKAP epigenome edited cells, and non-target epigenomically edited neurons exposed to degenerative IVD pH 6.5 conditioned media. *p < 0.05 compared with pH 6.5 control media; #p < 0.05 compared with non-target cells exposed to pH 6.5 conditioned media. Error bars are SD.

In addition, the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients was significantly elevated (p < 0.05) in naive neurons exposed to the low-pH degenerative IVD conditioned media group when compared with the low-pH control media group at temperatures less than or equal to 39°C (Figure 8E). However, when AKAP150 edited neurons were exposed to low-pH degenerative IVD conditioned media, sensitization was abolished, and the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients was not significantly different from the low-pH control media group at all temperatures tested (Figure 8E). From the curve fitting, the T50 value of AKAP150 epigenome edited neurons exposed to low-pH degenerative IVD conditioned media (38.7°C ± 0.41°C) was significantly higher than the T50 value of naive neurons (37.2°C ± 0.19°C; p < 0.05), yet not significantly different from the control media group (39.0°C ± 0.22°C) (Figure 8F).

Discussion

We modeled and investigated the interactions between the degenerative IVD environment and peripheral neurons to provide insight into the underlying mechanisms of discogenic back pain. We then developed novel CRISPR epigenome editing vectors to target the elevated nociceptive neuron activity that was observed. Our data demonstrate that degenerative IVD produces specific factors/cytokines capable of directly increasing DRG neuron activity in response to thermal stimuli, and the elevated neuron activity is further enhanced at pH levels experienced by neurons in the degenerative IVD, suggesting the degenerative IVD environment sensitizes peripheral neurons. This led to spontaneous calcium transients in neurons and a T50 activation threshold (37.32°C ± 0.39°C) near resting core body temperature, which was not observed after exposure to unconditioned media or media conditioned with healthy IVD. We demonstrated elevated levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R in degenerative IVD conditioned media and determined that blocking IL-6 in the conditioned media and AKAP150 in DRG neurons abolished this elevated neuron activity, indicating its induction by IL-6 and mediation by AKAP. Once the IL-6/AKAP pathway was established as mediating elevated nociceptive neuron activity, we investigated the ability of CRISPR epigenome editing of peripheral neurons to modulate the neuronal response to degenerative IVD exposure. Our data demonstrate that epigenome editing of AKAP150 expression in rat DRG neurons abolishes degenerative IVD-induced elevated nociceptive neuron activity to thermal stimuli while these neurons maintain their non-pathological calcium activation response. Together, these results implicate the synergistic effects of acidic pH and the activation of IL-6/AKAP as the underlying mechanism for degenerative IVD-induced neuron sensitization, demonstrate CRISPR epigenome editing of AKAP150 expression regulates neuron response to degenerative IVD, and establish CRISPR epigenome editing of nociceptive neurons as a possible gene-based neuromodulation strategy for discogenic pain and more broadly for inflammatory-driven pain.

We demonstrate that IL-6 released from degenerative IVDs elevates DRG neuron activity to noxious stimuli, particularly thermal stimuli. Previous studies have demonstrated increased cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) in painful IVDs7, 10, 11, 29, 30 and that inflammatory cytokines are capable of sensitizing rodents to thermal and mechanical stimuli in the paw in models of radiculopathy and peripheral neuropathy.32, 33, 49 Our findings demonstrate an ability for the degenerative IVD conditions, but not healthy IVD tissue, to directly lead to afferent neuron sensitization through the production and release of IL-6. These findings support our hypothesis that inflammation-driven sensitization of nociceptive neurons in the degenerative IVD could contribute to discogenic back pain via sensitization and establish an in vitro model, which can be used to study these interactions and screen novel therapeutics.

In this study, the degenerative IVD conditioned media combined with acidic pH was capable of inducing spontaneous calcium transients and a decrease in neuron heat-induced calcium transient thresholds, indicating sensitization of afferent neurons to noxious stimuli at temperatures as low as 37°C. Under degenerative IVD conditions, the T50 value (37.3°C) falls within the normal core body temperature range (36.1°C–37.8°C) and the Tmax is observed just above this range (38°C), with 13% of neurons exhibiting spontaneous calcium transients at the mean core temperature of 37°C. Previous studies have demonstrated shifts in the TRPV1 firing threshold in animal models of inflammation-induced thermal hyperalgesia,50, 51, 52, 53, 54 consistent with the decreased temperature thresholds observed in this study. Additionally, these shifts have been demonstrated to be AKAP79/150 dependent.53, 54, 55, 56 Because the majority of neurons innervating the IVD are nociceptive neurons that co-express CGRP, AKAP150, and TRPV1, an AKAP150-dependent pathological activation of TRPV1 at sub-38°C temperatures would provide a mechanism for nociceptive signaling in the degenerative IVD. These data suggest a novel role for AKAP150 in discogenic back pain because of synergistic pH and inflammatory cytokine-mediated sensitization.

Our data indicate that IL-6 trans-signaling mediates the neuron sensitization observed after exposure to degenerative IVD conditioned media. Multiple inflammatory cytokines have been observed in the pathological IVD, which includes TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8.7, 10, 11, 29, 30 IL-1β and TNF-α5, 29, 57 are the most common cytokines investigated in disc pathology due to their role in extracellular matrix breakdown and implication in rodent models of radiculopathy; however, our data demonstrate elevated levels of sIL-6R and IL-6 are present in degenerative IVD conditioned media and that blocking IL-6 action in the degenerative conditioned media abolished the elevated nociceptive neuron activity, demonstrating IL-6 as a primary mediator of inflammatory sensitization of neurons in these experiments. Notably, DRG neurons do not express membrane-bound IL-6 receptor, but rather IL-6 exhibits trans-signaling through a complex formed by IL-6, soluble IL-6 receptor, and glycoprotein 130 (gp130).33, 36 This implicates trans-signaling as a possible contributor to discogenic back pain and may indicate that the IL-6/sIL-6R/gp130 complex could be a target for therapeutic development for the treatment of discogenic back pain.

IL-6-induced sensitization in peripheral neuropathy and arthritis models has been observed because of increased phosphorylation of heat-sensitive ion channels and increased expression of heat-sensitive ion channels in sensitized neurons, or a combination of the two mechanisms. Consistent with these findings, our data suggest potential TRPV1 involvement. TRPV1 is a heat-sensitive ion channel38 expressed in nociceptive DRG neurons58 that innervate the healthy and pathological IVD that has been implicated in IL-6-induced thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathy models and can be sensitized via phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) or protein kinase C (PKC).53, 55 TRPV1 phosphorylation by PKA/PKC is regulated by AKAP150/79,53, 55 a scaffolding protein, that is co-expressed and co-localized with TRPV1 in DRG neurons53, 59 and mediates TRPV1 phosphorylation by facilitating interactions between PKA/PKC and TRPV1. As a result, we chose to investigate the potential role of AKAP-mediated TRPV1 sensitization by inhibiting AKAP150 via the inhibitor peptide St-HT31.55 When blocking the PKA/PKC binding site on AKAP150 with the inhibitor peptide St-HT31, degenerative IVD-induced thermal sensitization was abolished. These results indicated that AKAP150 was required for IL-6 induced by degenerative IVD. Additionally, the abolition of IL-6-induced thermal sensitization by inhibiting AKAP150 establishes AKAP150/79 as a potential therapeutic target in discogenic back pain and suggests TRPV1 involvement.

CRISPR epigenome editing systems have widespread potential to modulate cell function, and here we demonstrated their ability to alter DRG neuron response to degenerative IVD tissue. CRISPR-based epigenome editing allows for the local, long-term, and stable site-directed gene repression by H3K9 histone methylation. We hypothesized that degenerative IVD-induced sensitization of neurons could be regulated by epigenome editing of pain sensitization pathway genes in nociceptive neurons. Our data demonstrate that sensory neurons with epigenome modifications of the AKAP150 promoter maintained normal activation under conditions that sensitize non-edited neurons to noxious stimuli (i.e., IL-6 and acidic pH). These results demonstrate epigenome editing of pain-related genes in nociceptive neurons regulates sensitization and establishes epigenome modification as a potential therapeutic strategy for discogenic back pain treatment.

While we utilize this system to specifically target a gene of interest related to discogenic back pain, the robust expression of these systems in peripheral neurons opens the door for neuromodulation for a broad range of peripheral neuron disorders. These systems can be multiplexed,60 combined with orthogonal upregulating systems,61, 62 and incorporated into genetic circuits for complex cell control39, 63 in future work.

In this study, we demonstrated that degenerative IVD-released factors (IL-6), at degenerative IVD pH levels, synergistically increased neuron activation at sub-38°C temperatures through the IL-6/AKAP signaling pathway, which would provide a mechanism for nociceptive neuron firing in the degenerative IVD environment. In addition, we demonstrated epigenome editing of AKAP150 expression in sensory neurons prevented degenerative disc environment-triggered neuron sensitization to noxious stimuli. These results elucidate a primary therapeutic target and establish epigenome editing of nociceptive neurons as a treatment strategy for discogenic back pain. Future work will focus on determining the efficacy of epigenome editing gene regulation for broader regulation of nociceptive signaling in animal models of musculoskeletal pain.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Overview

A set of five experiments was conducted to investigate the role of key factors present in the degenerative IVD environment (i.e., inflammatory cytokines and low pH) on the sensitization of DRG neurons to noxious stimuli and to elucidate the specific factors and mechanisms mediating this sensitization. In the experiments in the Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section, rat DRG neurons were subjected to a range of temperatures during human degenerative and healthy IVD conditioned media exposure to determine the ability of factors released from degenerative IVD tissue to sensitize neurons and determine the magnitude of that sensitization. Following the degenerative IVD conditioned media exposure experiment, the experiments in the Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Cytokine Measurements section were conducted to identify which factors released from the degenerative IVD may contribute to sensitization. Subsequently, the experiments in the IL-6 Blocking Experiments section were performed to determine the role of IL-6 in the degenerative IVD sensitization of peripheral neurons. Once IL-6 was implicated as the primary mediator of neuron sensitization by human degenerative IVD, the experiments in the AKAP150 Inhibition Experiments section were conducted to determine the mechanism by which IL-6 sensitizes DRG neurons. Following AKAP implication in DRG sensitization, the experiments in the Acidic pH-Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section were conducted to determine the role of pH in DRG neuron sensitization and its ability to interact with the observed inflammation-driven sensitization.

Once the IL-6/AKAP150 pathway was implicated as the primary pathway for degenerative IVD-induced neuron sensitization, we investigated the potential of CRISPR epigenome editing of neurons to regulate degenerative IVD-induced sensitization via the targeting of AKAP150 in this pathway. Lentiviral constructs expressing the CRISPR epigenome editing system that targeted the AKAP150 gene promoter were designed, built, and validated for their ability to regulate AKAP150 expression in peripheral neurons. In addition, the ability of the CRISPR epigenome editing vectors targeting the AKAP150 to produce targeted histone methylation and the effect of methylation on the expression of adjacent genes were quantified. Validated CRISPR AKAP150 targeting epigenome editing vectors were selected and delivered to DRG neurons prior to exposure to degenerative IVD sensitization and acidic pH-degenerative IVD sensitization models, and tested for an ability to regulate previously demonstrated sensitization via the IL-6/AKAP150 pathway.

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media

IVD tissue was obtained from five patients undergoing surgical intervention for axial back pain, degenerative disc disease, and lumbar spondylosis. IVD tissue was extracted from lumbar discs for all patients. Patients showed signs of degenerative disc disease on MRI and reported axial back pain. Additionally, non-degenerative IVD tissue was obtained from three trauma patients with no prior history of axial back or neck pain. IVD tissue was transferred into a glass Petri dish, washed twice in washing medium (DMEM-high glucose [HG; Life Technologies] supplemented with 1% gentamycin [GIBCO], 1% kanamycin [Sigma], and 1% Fungizone [GIBCO]), and cut into small pieces (∼3 mm2). Next, the IVD tissue was weighed, transferred to a 75 cm2 tissue culture flask, and cultured in DMEM-HG supplemented with 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Life Technologies), 5 μg/mL gentamicin, and 0.125 μg/mL Fungizone at a media/tissue ratio of 3.5 ml/g for 48 hr (37°C and 5% CO2).28 After incubation, IVD conditioned media were collected and stored at −80°C until needed.

DRG Neuron Cell Culture

All procedures were performed with approval of the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Post-natal (p1–p4) Sprague-Dawley rat DRGs were explanted, placed in L-15 medium (GIBCO), and cleaned of anterior and posterior roots and connective tissue. Ganglia were dissociated in 2 mL of L-15 medium supplemented with 500 μL of collagenase IV (1.33%; Worthington Biochemical) for 30 min at 37°C. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 revolutions per minute (RPM) for 5 min after which the supernatant was aspirated and the cells were incubated in 4 mL of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1 mL of 1% trypsin (Worthington Biochemical) plus 50 μL of 1% DNase I (Worthington Biochemical) for 20 min at 37°C. Following incubation, 1 mL of soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI) (Worthington Biochemical) was added to the cell suspension, and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 RPM for 5 min. Next, the supernatant was aspirated, and cells were resuspended in 1 mL of DMEM/F12 plus 50 μL of 1% DNase and triturated through a fire polished Pasteur pipette. Rat DRG neurons were seeded onto laminin (Life Technologies)-coated 35 mm tissue culture dishes at a density of 50,000 cells per dish and cultured in 1.5 mL of SATO- medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2.2% SATO- mix, 1% transferrin [Sigma], 2% insulin [Sigma], 1% GlutaMAX [Invitrogen], 0.5% gentamicin, and 2.5S nerve growth factor [NGF; 10 ng/mL; Worthington Biochemical]) for 2–6 days until experiment.

Imaging of Heat-Induced Calcium Transients in DRG Neurons

Rat DRG neurons were loaded with the calcium indicator dye Fluo-4 AM (3 μM; Molecular Probes) and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 hr. Fluorescent measurements of calcium were performed using a multi-photon microscope (Prairie View [Bruker], excitation 810 nm, emission 545 nm, 0.5 Hz). Neurons were incubated at 37°C for 15 min to establish the baseline calcium signal and then exposed to heat stimuli for 2 min while imaging. Cells were returned to the baseline temperature for 5 min between exposures to elevated temperatures. 100 DRG neurons were imaged and analyzed for each sample.

Image analysis was conducted using Fiji software.64 The background signal was subtracted from each cell, and the mean baseline [F0(t)] was calculated at 37°C.

| (Equation 1) |

ΔF/F (Equation 1) was calculated for each cell across the entire experiment. The baseline mean and SD of ΔF/F were calculated for all cells at 37°C. Neurons were considered to exhibit calcium transients in response to heat stimuli if the ΔF/F for the cell was 3 SDs greater than the mean baseline value48 at 37°C (Figure 2) in response to heat stimulation. Calibration was performed to account for changes in calcium binding affinity of Fluo-4 AM with changes in temperature.

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure

Media were replaced with fresh SATO- media and 0.75 mL of unconditioned DMEM media (n = 5), degenerative IVD conditioned media (n = 5 patients), or healthy IVD conditioned media (n = 3 patients) and cultured for 24 hr (37°C, 5% CO2). Following incubation, neurons were loaded with the calcium-indicating dye Fluo-4 AM as described in the Imaging of Heat-Induced Calcium Transients in DRG Neurons section above. Neurons were incubated at 37°C for 15 min to establish a baseline calcium signal and then exposed to heat of 38°C, 39°C, 40°C, 42°C, and 44°C for 2 min while imaging. This temperature range was selected to cover the range expected at core body temperature up to a range that would ensure maximum firing response from the neurons and provide a full description of the activity of these neurons when exposed to degenerative IVD released factors. Cells were returned to the baseline temperature for 5 min between exposures to elevated temperatures.

Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Cytokine Measurements

The levels of IL-6, sIL-6R, TNF-α, and IL-1β in degenerative IVD conditioned media (n = 11 patients) and healthy IVD conditioned media (n = 3 patients) were measured using commercially available assay kits (Thermo Fisher) and following the manufacturer’s instructions.

IL-6 Blocking Experiments

Mouse monoclonal anti-human IL-6 antibody (20 μg/mL; Life Technologies) or mouse isotype control antibody (20 μg/mL; Life Technologies) were added to degenerative IVD conditioned media and incubated at 37°C for 3 hr prior to addition to neurons as described in the Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section (n = 5 patients). Degenerative IVD conditioned media not receiving antibody treatment and control media (DMEM supplemented with 5 μg/mL gentamicin and 0.125 μg/mL Fungizone) were incubated at 37°C for 3 hr prior to addition to neurons as described in the Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section (n = 5). Neurons were incubated at 37°C for 15 min to establish a baseline calcium signal and then exposed to heat stimulation of 38°C, 39°C, 40°C, 42°C, and 44°C for 2 min while imaging. Cells were returned to the baseline temperature for 5 min between exposures to elevated temperatures.

AKAP150 Inhibition Experiments

DRG neurons were loaded with the calcium dye Fluo-4 AM (3 μM) and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 hr. The AKAP150 inhibitor peptide St-Ht31 (50 μM; Promega) or the control peptide St-Ht31P (50 μM; Promega) was added to the DRG neurons and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Following incubation, degenerative IVD conditioned media (n = 3 patients) or control media were added to the peptide-exposed neurons and incubated for 15 min (n = 3). Additionally, separate groups of neurons were exposed to control media or degenerative IVD conditioned media without peptide exposure under the same conditions (n = 3 patients). Following this incubation, a 15 min baseline calcium signal at 37°C was established, and cells were exposed to heat stimulation of 39°C while imaging.

Acidic pH-Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure

Experiments were conducted as described in the Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section (n = 4 patients) with the following experimental treatment groups: normal pH (7.4) control media (DMEM), normal pH (7.4) IVD conditioned media, low-pH (6.5) control media, and low-pH (6.5) IVD conditioned media. Control media (DMEM) or degenerative IVD conditioned media were equilibrated in an incubator for 24 hr (37°C, 5% CO2). Following incubation, the pH of the acidic pH groups was lowered to a pH of 6.5 by the addition of HCl (1 M; Sigma-Aldrich), and the normal pH groups were maintained at a pH of 7.4. Normal and low pH levels were selected based on previously reported pH levels in healthy and degenerative IVD tissue, to which peripheral neurons innervating the disc would be exposed.31, 65

Lentiviral CRISPR Epigenome Editing Vector Construction

We created CRISPR epigenome editing vectors that co-express dCAS-KRAB-T2A-GFP and gRNAs that target AKAP150 (Figures 7A and 7B). First, the promoter region of AKAP150 is screened for gRNA target sequences with the necessary adjacent protospacer adjacent motif (PAM: -NGG) and selected based on minimizing off-target binding sites using a publically available algorithm.66 Four guides were selected and screened for the AKAP promoter region (data and sequences obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz [UCSC] genome browser67). The non-target guide oligonucleotide was designed as a scramble DNA sequence that does not match the rat genome. Oligonucleotides are obtained (University of Utah DNA/Peptide Synthesis Core), hybridized, phosphorylated, and cloned into gRNA expressing plasmids (Addgene plasmid 47108) using BbsI sites. To produce a lentiviral vector that co-expresses dCAS-KRAB-T2A-GFP and gRNA, gRNA cassette are cloned via PCR and inserted into third generation lentiviral transfer vector that expresses dCas-KRAB-T2A-GFP under the control of the human ubiquitin C (UbC) promoter via BsmBI sites. In addition, vesicular somatic glycoprotein (VSV-G) pseudotype lentivirus with UbC promoter was utilized because of a demonstrated ability to transduce neurons at high efficiciency.68, 69, 70, 71 Epigenome editing vector constructs were produced in HEK293T cells using a previously reported method,72 concentrated, and stored at −80°C until use, to produce transduction media (DMEM). For transduction of rat DRG neurons, media were removed and replaced with transduction media supplemented with polybrene (8 μg/mL), and cells were cultured for 24 hr. The next day, viral media were removed and replaced with fresh SATO- medium. Transduced DRG neurons were cultured in SATO- medium under standard cell culture conditions until experiments were performed.

qRT-PCR

Four days following transduction, cells were harvested for total RNA using the PureLink RNA microscale kit (Life Technologies) (n = 3). cDNA synthesis was conducted using the High Capacity cDNA RT kit (Life Technologies). qRT-PCR using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) was performed with the TaqMan Gene Expression Detection Assay (Life Technologies) with oligonucleotide primers for AKAP150, Zbtb25, Mthfd1, and GAPDH. Results are expressed as fold increase in mRNA expression of AKAP150, Zbtb25, or Mthfd1 normalized to GAPDH expression using the ΔΔ Ct method.

AKAP150 Immunocytochemistry Experiments

Rat DRG neurons were seeded onto laminin-coated chamber slides (Fisher Scientific) at a density of 14,000 cells per chamber and cultured in SATO- medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2.2% SATO mix, 1% transferrin [Sigma], 2% insulin [Sigma], 1% GlutaMAX [Invitrogen], 0.5% gentamicin, and 2.5S NGF [10 ng/mL; Worthington Biochemical]) for 2 days until transduction (as described in the Lentiviral CRISPR Epigenome Editing Vector Construction section).

Four days following transduction, media were removed and cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 20 min. Following fixation, cells were washed three times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X (in PBS) for 5 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were washed three times with PBS and treated with blocking solution (5% goat serum [Thermo Fisher Scientific] in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature). After blocking, blocking solution was removed and cells were treated with anti-AKAP150 antibody (1:200 in goat serum; EMP Millipore) or normal rabbit IgG (Calbiochem) or serum only for negative controls, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Following overnight incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS, treated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (1:200; Millipore), and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were rinsed three times with PBS, treated with DAPI solution (3 ng/mL) for 10 min, and mounted with Prolong Diamond Antifade Reagent (Thermo Fisher) prior to imaging. Cells were imaged using a multi-photon microscope (Prairie View [Bruker], 20× objective).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation qPCR Experiments

Rat DRG neurons were seeded at a density of 250,000 neurons on laminin-coated 100 mm dishes, as described in the DRG Neuron Cell Culture section above. Individual transductions of DRG neurons with epigenome editing lentiviral constructs targeting the AKAP150 gene promoter region or a non-target gRNA were performed as described in the Lentiviral CRISPR Epigenome Editing Vector Construction section above. Seven days following transduction, 250,000 neurons were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, and chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described73 using an anti-H3K9me3 antibody (ab8898; Abcam). Sonication was performed on an Active Motif EpiShear probe-in sonicator with eight cycles of 30 s, with 30 s of rest, at 40% amplitude. Purified DNA was analyzed using Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher) with the following primers: AKAP promoter: forward 5′-CTCCCCCTTTGCCTTAGTG-3′, reverse 5′-ATCCCCGCTGCATAATGAC-3′; and GAPDH promoter: forward 5′-GAACAGGGAGGAGCAGAGAG-3′, reverse 5′-CCCCACCATCCAGTTCCTAT-3′. One fourth of the purified DNA was used for each qPCR, and 50 cycles, with an annealing temperature of 60°C, were performed. Cycle thresholds were calculated, and the GAPDH promoter (a negative control) was used to normalize the AKAP promoter. Two replicates of AKAP promoter targeting were analyzed by t test, and each was significantly different from the controls (p < 0.05).

AKAP150 Epigenome Edited Neurons Conditioned Media Exposure

After verifying AKAP150 regulation via epigenome editing, DRG neurons were transduced with verified epigenome editing lentiviral constructs targeting the AKAP150 gene promoter region or a non-target gRNA, as described above, and cultured in SATO- medium for 4 days following removal of lentivirus. Successful transduction was verified via fluorescent imaging of GFP in transduced neurons. Following the culture period, transduced (AKAP150 targeting and non-targeting control) and naive (non-transduced) DRG neurons were exposed to normal pH (7.4) control media (DMEM), normal pH (7.4) IVD conditioned media, low-pH (6.5) control media, or low-pH (6.5) IVD conditioned media and incubated for 24 hr. Media pH were adjusted as described in the Acidic pH-Degenerative IVD Conditioned Media Exposure section. Following incubation, neurons were loaded with the calcium indicator dye rhod-2 AM (3 μM; Molecular Probes) and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 hr. Fluorescent measurements of calcium were performed using a multi-photon microscope (Prairie View [Bruker], excitation 1105 nm, emission 585 nm, 0.5 Hz). Neurons were incubated at 37°C for 15 min to establish a baseline calcium signal and then exposed to heat stimuli of 38°C, 39°C, 40°C, 42°C, and 44°C for 2 min while imaging. Cells were returned to the baseline temperature for 5 min between exposures to elevated temperatures.

Curve Fitting of Neuron Calcium Transients

Data from the conditioned media and IL-6 blocking experiments were fit to the sigmoidal Boltzmann equation with the percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients plotted as a function of temperature.

| (Equation 2) |

Each trial was individually fit to produce values for T50 and max. T50 was defined as the temperature at which 50% of the maximum response occurs. The Tmax was defined as the maximum percentage of neurons exhibiting heat-induced calcium transients predicted by the curve fitting.

Statistical Analysis

Degenerative IVD conditioned media exposure, IL-6 blocking experiment, degenerative IVD pH level, and AKAP150 epigenome edited neuron conditioned media exposure experiment data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA on repeated measures with Tukey’s post hoc test, treating media condition and temperature as factors. AKAP inhibitor experiment data, T50, and maximum response data from IL-6 blocking experiments were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, treating media condition as the factor. qPCR experiments were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, treating CRISPR epigenome editing vector treatment as the factor. Chromatin immunoprecipitation qPCR experiments were analyzed by t test comparing AKAP edited neurons with non-targeting control. IVD conditioned media cytokine measurements were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks, treating media condition as the factor. Significance was tested at α = 0.05 for all statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.S., B.L., R.D.B., and J.G.; Investigation, J.D.S., N.F., and K.C.B.; Writing – Original Draft, J.D.S., J.G., and R.D.B.; Writing – Review and Editing, J.D.S., N.F., K.C.B., J.G., B.L., and R.D.B.; Funding Acquisition, B.L., J.G., and R.D.B.; Resources, B.L., J.G., and R.D.B.; Supervision, B.L., J.G., and R.D.B.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the NIH under award R03AR068777. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank Elena Budko for her expertise in DRG neuron harvesting and cell culture.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes one figure and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.010.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Vos T., Barber R.M., Bell B., Bertozzi-Villa A., Biryukov S.B.I., Bolliger I., Charlson F., Davis A., Degenhardt L., Dicker D., Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray C.J., Vos T., Lozano R., Naghavi M., Flaxman A.D., Michaud C., Ezzati M., Shibuya K., Salomon J.A., Abdalla S. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz J.N. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21–24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts S., Evans H., Trivedi J., Menage J. Histology and pathology of the human intervertebral disc. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):10–14. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Maitre C.L., Hoyland J.A., Freemont A.J. Catabolic cytokine expression in degenerate and herniated human intervertebral discs: IL-1beta and TNFalpha expression profile. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007;9:R77. doi: 10.1186/ar2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suthar P., Patel R., Mehta C., Patel N. MRI evaluation of lumbar disc degenerative disease. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015;9:TC04–TC09. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11927.5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke J.G., Watson R.W., McCormack D., Dowling F.E., Walsh M.G., Fitzpatrick J.M. Intervertebral discs which cause low back pain secrete high levels of proinflammatory mediators. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2002;84:196–201. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b2.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke J.G., G Watson R.W., Conhyea D., McCormack D., Dowling F.E., Walsh M.G., Fitzpatrick J.M. Human nucleus pulposis can respond to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. Spine. 2003;28:2685–2693. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000103341.45133.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokubo Y., Uchida K., Kobayashi S., Yayama T., Sato R., Nakajima H., Takamura T., Mwaka E., Orwotho N., Bangirana A., Baba H. Herniated and spondylotic intervertebral discs of the human cervical spine: histological and immunohistological findings in 500 en bloc surgical samples. Laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2008;9:285–295. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/9/285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamji M.F., Setton L.A., Jarvis W., So S., Chen J., Jing L., Bullock R., Isaacs R.E., Brown C., Richardson W.J. Proinflammatory cytokine expression profile in degenerated and herniated human intervertebral disc tissues. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1974–1982. doi: 10.1002/art.27444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Specchia N., Pagnotta A., Toesca A., Greco F. Cytokines and growth factors in the protruded intervertebral disc of the lumbar spine. Eur. Spine J. 2002;11:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0361-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernon-Roberts B., Moore R.J., Fraser R.D. The natural history of age-related disc degeneration: the pathology and sequelae of tears. Spine. 2007;32:2797–2804. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b64d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melrose J., Roberts S., Smith S., Menage J., Ghosh P. Increased nerve and blood vessel ingrowth associated with proteoglycan depletion in an ovine anular lesion model of experimental disc degeneration. Spine. 2002;27:1278–1285. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freemont A.J., Watkins A., Le Maitre C., Baird P., Jeziorska M., Knight M.T., Ross E.R., O’Brien J.P., Hoyland J.A. Nerve growth factor expression and innervation of the painful intervertebral disc. J. Pathol. 2002;197:286–292. doi: 10.1002/path.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coppes M.H., Marani E., Thomeer R.T., Oudega M., Groen G.J. Innervation of annulus fibrosis in low back pain. Lancet. 1990;336:189–190. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91723-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freemont A.J., Peacock T.E., Goupille P., Hoyland J.A., O’Brien J., Jayson M.I. Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain. Lancet. 1997;350:178–181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risbud M.V., Shapiro I.M. Role of cytokines in intervertebral disc degeneration: pain and disc content. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014;10:44–56. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Cosamalón J., del Valle M.E., Calavia M.G., García-Suárez O., López-Muñiz A., Otero J., Vega J.A. Intervertebral disc, sensory nerves and neurotrophins: who is who in discogenic pain? J. Anat. 2010;217:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lotz J.C., Ulrich J.A. Innervation, inflammation, and hypermobility may characterize pathologic disc degeneration: review of animal model data. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):76–82. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kepler C.K., Ponnappan R.K., Tannoury C.A., Risbud M.V., Anderson D.G. The molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. 2013;13:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki Y., Ohtori S., Takahashi K., Ino H., Takahashi Y., Chiba T., Moriya H. Innervation of the lumbar intervertebral disc by nerve growth factor-dependent neurons related to inflammatory pain. Spine. 2004;29:1077–1081. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aoki Y., Ohtori S., Takahashi K., Ino H., Douya H., Ozawa T., Saito T., Moriya H. Expression and co-expression of VR1, CGRP, and IB4-binding glycoprotein in dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats: differences between the disc afferents and the cutaneous afferents. Spine. 2005;30:1496–1500. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000167532.96540.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohtori S., Takahashi K., Chiba T., Yamagata M., Sameda H., Moriya H. Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactive sensory DRG neurons innervating the lumbar intervertebral discs in rats. Ann. Anat. 2002;184:235–240. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(02)80113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashton I.K., Roberts S., Jaffray D.C., Polak J.M., Eisenstein S.M. Neuropeptides in the human intervertebral disc. J. Orthop. Res. 1994;12:186–192. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kestell G.R., Anderson R.L., Clarke J.N., Haberberger R.V., Gibbins I.L. Primary afferent neurons containing calcitonin gene-related peptide but not substance P in forepaw skin, dorsal root ganglia, and spinal cord of mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015;523:2555–2569. doi: 10.1002/cne.23804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson W.E., Evans H., Menage J., Eisenstein S.M., El Haj A., Roberts S. Immunohistochemical detection of Schwann cells in innervated and vascularized human intervertebral discs. Spine. 2001;26:2550–2557. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown M.F., Hukkanen M.V., McCarthy I.D., Redfern D.R., Batten J.J., Crock H.V., Hughes S.P., Polak J.M. Sensory and sympathetic innervation of the vertebral endplate in patients with degenerative disc disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1997;79:147–153. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b1.6814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krock E., Rosenzweig D.H., Chabot-Doré A.J., Jarzem P., Weber M.H., Ouellet J.A., Stone L.S., Haglund L. Painful, degenerating intervertebral discs up-regulate neurite sprouting and CGRP through nociceptive factors. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014;18:1213–1225. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Maitre C.L., Pockert A., Buttle D.J., Freemont A.J., Hoyland J.A. Matrix synthesis and degradation in human intervertebral disc degeneration. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:652–655. doi: 10.1042/BST0350652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Maitre C.L., Richardson S.M.A., Baird P., Freemont A.J., Hoyland J.A. Expression of receptors for putative anabolic growth factors in human intervertebral disc: implications for repair and regeneration of the disc. J. Pathol. 2005;207:445–452. doi: 10.1002/path.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitano T., Zerwekh J.E., Usui Y., Edwards M.L., Flicker P.L., Mooney V. Biochemical changes associated with the symptomatic human intervertebral disk. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993;293:372–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oprée A., Kress M. Involvement of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1 beta, and IL-6 but not IL-8 in the development of heat hyperalgesia: effects on heat-evoked calcitonin gene-related peptide release from rat skin. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6289–6293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06289.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obreja O., Schmelz M., Poole S., Kress M. Interleukin-6 in combination with its soluble IL-6 receptor sensitises rat skin nociceptors to heat, in vivo. Pain. 2002;96:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obreja O., Biasio W., Andratsch M., Lips K.S., Rathee P.K., Ludwig A., Rose-John S., Kress M. Fast modulation of heat-activated ionic current by proinflammatory interleukin 6 in rat sensory neurons. Brain. 2005;128:1634–1641. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oka Y., Ibuki T., Matsumura K., Namba M., Yamazaki Y., Poole S., Tanaka Y., Kobayashi S. Interleukin-6 is a candidate molecule that transmits inflammatory information to the CNS. Neuroscience. 2007;145:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andratsch M., Mair N., Constantin C.E., Scherbakov N., Benetti C., Quarta S., Vogl C., Sailer C.A., Uceyler N., Brockhaus J. A key role for gp130 expressed on peripheral sensory nerves in pathological pain. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:13473–13483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1822-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang D., Kong L.Y., Cai J., Li S., Liu X.D., Han J.S., Xing G.G. Interleukin-6-mediated functional upregulation of TRPV1 receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons through the activation of JAK/PI3K signaling pathway: roles in the development of bone cancer pain in a rat model. Pain. 2015;156:1124–1144. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caterina M.J., Schumacher M.A., Tominaga M., Rosen T.A., Levine J.D., Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thakore P.I., Black J.B., Hilton I.B., Gersbach C.A. Editing the epigenome: technologies for programmable transcription and epigenetic modulation. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:127–137. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J.A., Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P.D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L.A., Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mali P., Esvelt K.M., Church G.M. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:957–963. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sripathy S.P., Stevens J., Schultz D.C. The KAP1 corepressor functions to coordinate the assembly of de novo HP1-demarcated microenvironments of heterochromatin required for KRAB zinc finger protein-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8623–8638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groner A.C., Meylan S., Ciuffi A., Zangger N., Ambrosini G., Dénervaud N., Bucher P., Trono D. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krebs C.J., Schultz D.C., Robins D.M. The KRAB zinc finger protein RSL1 regulates sex- and tissue-specific promoter methylation and dynamic hormone-responsive chromatin configuration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:3732–3742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00615-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds N., Salmon-Divon M., Dvinge H., Hynes-Allen A., Balasooriya G., Leaford D., Behrens A., Bertone P., Hendrich B. NuRD-mediated deacetylation of H3K27 facilitates recruitment of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 to direct gene repression. EMBO J. 2012;31:593–605. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grienberger C., Konnerth A. Imaging calcium in neurons. Neuron. 2012;73:862–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greffrath W., Kirschstein T., Nawrath H., Treede R. Changes in cytosolic calcium in response to noxious heat and their relationship to vanilloid receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;104:539–550. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowles R.D., Karikari I.O., VanDerwerken D.N., Sinclair M.S., Bell R.D., Riebe K.J., Huebner J.L., Kraus V.B., Sempowski G.D., Setton L.A. In vivo luminescent imaging of NF-κB activity and NF-κB-related serum cytokine levels predict pain sensitivities in a rodent model of peripheral neuropathy. Eur. J. Pain. 2016;20:365–376. doi: 10.1002/ejp.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banik R.K., Brennan T.J. Trpv1 mediates spontaneous firing and heat sensitization of cutaneous primary afferents after plantar incision. Pain. 2009;141:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis J.B., Gray J., Gunthorpe M.J., Hatcher J.P., Davey P.T., Overend P., Harries M.H., Latcham J., Clapham C., Atkinson K. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rathee P.K., Distler C., Obreja O., Neuhuber W., Wang G.K., Wang S.Y., Nau C., Kress M. PKA/AKAP/VR-1 module: a common link of Gs-mediated signaling to thermal hyperalgesia. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:4740–4745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04740.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeske N.A., Diogenes A., Ruparel N.B., Fehrenbacher J.C., Henry M., Akopian A.N., Hargreaves K.M. A-kinase anchoring protein mediates TRPV1 thermal hyperalgesia through PKA phosphorylation of TRPV1. Pain. 2008;138:604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schnizler K., Shutov L.P., Van Kanegan M.J., Merrill M.A., Nichols B., McKnight G.S., Strack S., Hell J.W., Usachev Y.M. Protein kinase A anchoring via AKAP150 is essential for TRPV1 modulation by forskolin and prostaglandin E2 in mouse sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:4904–4917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0233-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeske N.A., Patwardhan A.M., Ruparel N.B., Akopian A.N., Shapiro M.S., Henry M.A. A-kinase anchoring protein 150 controls protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and sensitization of TRPV1. Pain. 2009;146:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X., Li L., McNaughton P.A. Proinflammatory mediators modulate the heat-activated ion channel TRPV1 via the scaffolding protein AKAP79/150. Neuron. 2008;59:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shamji, M. F., Setton, L.A., Jarvis, W., So, S., Chen, J., Jing, L., Bullock, R., Isaacs, R.E., Brown, C., and Richardson, W.J. (2010). Proinflammatory cytokine expression profile in degenerated and herniated human intervertebral disc tissues. 62, 1974–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Brandao K.E., Dell’Acqua M.L., Levinson S.R. A-kinase anchoring protein 150 expression in a specific subset of TRPV1- and CaV 1.2-positive nociceptive rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012;520:81–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.22692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Btesh J., Fischer M.J.M., Stott K., McNaughton P.A. Mapping the binding site of TRPV1 on AKAP79: implications for inflammatory hyperalgesia. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:9184–9193. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4991-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kabadi A.M., Ousterout D.G., Hilton I.B., Gersbach C.A. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome engineering from a single lentiviral vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esvelt K.M., Mali P., Braff J.L., Moosburner M., Yaung S.J., Church G.M. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dahlman J.E., Abudayyeh O.O., Joung J., Gootenberg J.S., Zhang F., Konermann S. Orthogonal gene knockout and activation with a catalytically active Cas9 nuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1159–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brophy J.A.N., Voigt C.A. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:508–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diamant B., Karlsson J., Nachemson A. Correlation between lactate levels and pH in discs of patients with lumbar rhizopathies. Experientia. 1968;24:1195–1196. doi: 10.1007/BF02146615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu P.D., Scott D.A., Weinstein J.A., Ran F.A., Konermann S., Agarwala V., Li Y., Fine E.J., Wu X., Shalem O. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kent W.J., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kordower J.H., Bloch J., Ma S.Y., Chu Y., Palfi S., Roitberg B.Z., Emborg M., Hantraye P., Déglon N., Aebischer P. Lentiviral gene transfer to the nonhuman primate brain. Exp. Neurol. 1999;160:1–16. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Déglon N., Tseng J.L., Bensadoun J.C., Zurn A.D., Arsenijevic Y., Pereira de Almeida L., Zufferey R., Trono D., Aebischer P. Self-inactivating lentiviral vectors with enhanced transgene expression as potential gene transfer system in Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000;11:179–190. doi: 10.1089/10430340050016256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naldini L., Blömer U., Gage F.H., Trono D., Verma I.M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watson D.J., Kobinger G.P., Passini M.A., Wilson J.M., Wolfe J.H. Targeted transduction patterns in the mouse brain by lentivirus vectors pseudotyped with VSV, Ebola, Mokola, LCMV, or MuLV envelope proteins. Mol. Ther. 2002;5:528–537. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salmon P., Trono D. Production and titration of lentiviral vectors. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2006;Chapter 4:Unit 4.21. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0421s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reddy T.E., Pauli F., Sprouse R.O., Neff N.F., Newberry K.M., Garabedian M.J., Myers R.M. Genomic determination of the glucocorticoid response reveals unexpected mechanisms of gene regulation. Genome Res. 2009;19:2163–2171. doi: 10.1101/gr.097022.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.