Abstract

Renal T-cell infiltration is a key component of salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Here we use an electronic servo-control technique to determine the contribution of renal perfusion pressure to T-cell infiltration in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat kidney. An aortic balloon occluder placed around the aorta between the renal arteries was used to maintain perfusion pressure to the left kidney at control levels, approximately 128 mmHg, during 7-days of salt-induced hypertension while the right kidney was exposed to increased renal perfusion pressure which averaged 157 ± 4 mmHg by high salt day-7. The number of infiltrating T-cells was compared between the two kidneys. Renal T-cell infiltration was significantly blunted in the left servo-controlled kidney compared to the right uncontrolled kidney. The number of CD3+, CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T-cells were all significantly lower in the left servo-controlled kidney. This effect was not specific to T-cells since CD45R+ (B-cells) and CD11b/c+ (monocytes and macrophages) cell infiltrations were all exacerbated in the hypertensive kidneys. Increased renal perfusion pressure was also associated with augmented renal injury, with increased protein casts and glomerular damage in the hypertensive kidney. Levels of norepinephrine were comparable between the two kidneys, suggestive of equivalent sympathetic innervation. Renal infiltration of T-cells was not reversed by the return of renal perfusion pressure to control levels after 7-days of salt-sensitive hypertension. We conclude that increased pressure contributes to the initiation of renal T-cell infiltration during the progression of salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats.

Keywords: Salt-sensitivity, Immune System, Kidney, Lymphocytes, Rats

Introduction

In recent years the role of the immune system in the development of hypertension has received increased attention. Renal immune cell infiltration has been demonstrated in both experimental and clinical hypertension, with lymphocytes and macrophages localizing to regions of injury1–5. Importantly, experimental studies utilizing an adoptive transfer approach in immunodeficient mice demonstrated the importance of T-lymphocytes in the development of experimental hypertension6.

Work in our laboratory indicates that T-cells play a pivotal role in the amplification of salt-sensitive hypertension in SS rats2. In SS rats, as in the clinical condition, hypertension is a genetically determined progressive disease, which culminates in renal injury, albuminuria, increased oxidative stress and reduced glomerular filtration rate7–10. Defining the mechanisms involved in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension in the SS rats is therefore of clinical interest. Increased renal T-cell infiltration has been demonstrated in SS rats maintained on 4.0% NaCl high salt diet for 3-weeks compared to those maintained on a 0.4% NaCl control salt diet11,12. We have also demonstrated that pharmacological or genetic inhibition of immune cell function reduces the infiltration of immune cells into the kidneys of SS rats which is associated with the attenuation of both salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury11–15. Interestingly, selective mutation of a component of the T-cell receptor complex (CD247) attenuated salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage in SS rats13. In this model the protective effects of T-cell mutation became apparent during the later stages of disease progression, with blood pressure being significantly lower than that of the salt-sensitive rats from days 14–21 of a high salt diet13. From these data, we hypothesize that infiltrating immune cells serve to amplify the development of salt-sensitive hypertension in the SS rat.

Despite strong evidence supporting the involvement of T-cells in both clinical and experimental hypertension, the signals involved in the initiation of renal infiltration remain elusive. Previous servo-control studies from our laboratory, in which pressure to the left kidney of SS rats was maintained at the control level, whilst the right was exposed to salt-induced hypertension, have demonstrated an association between increased blood pressure, renal macrophage infiltration and renal injury16. ED-1 staining to quantify macrophages in the glomerular tuft demonstrated increased infiltration in the uncontrolled hypertensive kidneys compared to the servo-controlled kidneys16. Based on these data we hypothesized that exposure to elevated blood pressure is a prerequisite for renal T-cell infiltration in salt-sensitive hypertension in SS rats.

In the current study, chronic servo-control experiments were used to determine the role of increased blood pressure in renal T-cell infiltration in SS rats. A custom designed and built computer driven servo-control system, which we have previously described17, was used to maintain pressure to the left kidney at control levels during 7-days administration of a 4.0% NaCl diet, whereas the right kidney was exposed to a progressive increase in pressure. In a subsequent study we used the servo-control system to return pressure to the left kidney back to control levels after 7-days of salt-sensitive hypertension. The results of these studies provide strong evidence that augmented T-cell infiltration occurs in response to a rise of arterial pressure in the early phase of hypertension in the SS rat.

Methods

Experimental Animals

Male SS/JrHsdMcwi (SS) rats were obtained at weaning from a colony developed and maintained at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Breeders and offspring at weaning were fed a purified AIN-76A rodent food diet (Dyets, Bethleham, PA) containing 0.4% NaCl with ab libitum water. The high salt diet (HS) contained 4.0% NaCl. All experimental protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical Preparation

Prior to surgery all rats were trained to a bidirectional turntable cage system (Rodent Workstation with Raturn system; Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN) for a minimum of 7-days. Rats were surgically prepared, under isoflurane anesthetic, at 9–12 weeks as we have previously described18. In brief, an inflatable silastic occluder attached to Tygon tubing was placed around the aorta, between the renal arteries. The Tygon tubing was tunneled subcutaneously and exited at the nape of the neck. The occluder was connected to a custom made infusion pump with a stepper motor (MDrive23, Intelligent Motion systems, Marlborough, CT). Catheters were implanted in the femoral vein, for the administration of analgesics and anesthetic, and the carotid and femoral arteries for the measurement of mean arterial pressure above and below the occluder. All catheters were tunneled subcutaneously and exited at the nape of the neck. Sham rats were prepared identically, however the occluder cuff was not inflated. All rats had 7-days recovery after surgery, prior to the initiation of blood pressure measurements.

Servo-Control Protocol

Throughout the study saline was continuously infused into the venous catheter at 6.9 μl/min and mean arterial pressure was recorded 24hr/day from both carotid and femoral catheters. Baseline measurements were made over 3-days to obtain stable control measurements while the rats were maintained on 0.4% NaCl control diet. Subsequently, the salt content of the diet was increased to 4.0% and measurements continued for a further 7-days. During the consumption of a 4.0% NaCl high salt (HS) diet renal perfusion pressure (RPP) to the left kidney was continuously maintained moment to moment within ±5 mmHg of the average control value. A sham group of rats underwent an identical surgical and experimental protocol; however, the vascular occluder cuff was not inflated during the study and both kidneys were exposed to salt-induced hypertension. In the reversal study baseline measurements were made over 3-days while the rats were fed 0.4% NaCl. The rats were then switched to 4.0% NaCl for 7-days, during this period the aortic occluder was not inflated and both kidneys were exposed to salt-sensitive hypertension. After 7-days of 4.0% NaCl the occluder was inflated to bring the RPP to the left kidney back to the control level, where it was maintained for a further 7-days.

Tissue Collection

Servo-control of RPP to the left kidney was continued throughout the tissue collection to prevent exposure of the left kidney to an uncontrolled pressure. Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50mg/kg i.v) and both kidneys were flushed with saline. The upper pole of each kidney was removed for T-cell isolation. A thin slice, 2mm around the papilla, was cut and fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution for histological analysis. The bottom pole was snap frozen and RNA isolated for qPCR analysis.

T-Cell isolation

To isolate mononuclear cells we used our previously described protocol14 with some modifications. Kidneys were minced with razor blade, pressed through a 100μm cell strainer (Falcon by Corning) and digested in 10ml of RPMI-1640 (Gibco by Life Technologies) containing 0.1% of collagenase type IV (Worthington) and 10μg/ml (or 230U) of DNAse I (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 25min. After incubation the kidney homogenate was diluted with DPBS (Gibco by Life Technologies), containing 2% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals) and 2mM EDTA (Invitrogen by Life Technologies) (wash buffer), filtered through a 70 μm strainer and centrifuged at 4°C at 300g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 5ml of wash buffer and after filtering through a 40μm cell strainer, centrifuged at 4°C at 350g for 7min. To isolate the mononuclear cells the obtained pellet was either resuspended in 3ml of FBS containing 10mM EDTA, layered over Histopaque-1083 (Sigma-Aldrich) or resuspended in 30% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich, DPBS,1X as diluent) and layered over 70% Percoll and centrifuged at 20°C at 400g for 30 min. The isolated mononuclear cells were collected, washed twice with wash buffer at 4°C at 400g for 5 min and counted on hemocytometer. For flowcytometry analysis cells were resuspended in 100 μl of DPBS containing 0.5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) (stain buffer), stained with the following monoclonal fluorochrome-labeled antibodies: anti-rat CD45 – PE-Cy7 (BioLegend, Clone OX-1), anti-rat CD3 - PerCP-eFluor 710 (eBioscience, Clone G4.18), anti-rat CD8a – FITC (BioLegend, Clone OX-8), anti-rat CD4 – APC-Cy7 (BioLegend, Clone W3/25), anti-rat CD45R – PE (BD Bioscience, Clone HIS24), anti-rat CD11b/c - eFluor 660 (eBioscience, Clone OX-42) and analyzed on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) with FACSDiva software. Data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva and FlowJo software. The isolation of cells from the kidney, the cell counting step, and the flow cytometric analysis were performed in a blinded manner. The gating strategy is shown in Figure S1.

Histological Analysis

The formalin-fixed tissue was paraffin embedded, cut in 4μm sections, mounted and stained with Gomori’s one-step Trichrome. Tubular protein casts and glomeruli injury were quantified as previously described11. Glomeruli were scored by a blinded observer on a scale from 0–4. Two distinct populations were scored, cortical and juxtamedullary glomeruli, determined by their depth in the kidney. Separate sections were stained with CD3+ (Anti-human CD3; 1:100; DAKO) for qualitative assessment of T-cell localization.

Norepinephrine Assay

In five sham rats the lower pole of each kidney was isolated and snap frozen for the analysis of tissue norepinephrine levels by HPLC to determine if surgical placement or the chronic presence of the aortic occluder produced injury of renal nerves and denervation of the kidneys.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. For mean arterial pressure data within group differences were assessed used a Two Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance followed by a Holm-Sidak test for multiple comparisons versus the average control pressure and the RPP to the left kidney. Renal norepinephrine levels and kidney weight were compared using a two-tailed paired t-test. For comparison of infiltrating immune cells, tubular protein casts and glomeruli injury in the left and right kidney data were analyzed using a two-tailed paired t-test or Wilcoxon Signed Rank test as appropriate.

Results

Chronic servo-control of renal perfusion pressure to the left kidney of conscious SS rats

Figure 1 summarizes RPP in the servo-controlled (Figure 1A) and sham (Figure 1B) rats. During 7-days of 4.0% NaCl consumption RPP to the right-uncontrolled kidneys increased progressively in the servo-controlled rats, from 133±2 mmHg during the 0.4% NaCl control period to 157±4 mmHg at HS day-7. RPP to the right kidneys was significantly higher than the average control value from HS day-1 onwards (p<0.001). In contrast pressure to the left servo-controlled kidneys was maintained at control levels throughout the study, with HS day-7 values, 127±1 mmHg, being equivalent to those recorded during the 0.4% NaCl period, 129±2 mmHg (Figure 1A). Compression of the aorta by the inflatable occluder was reflected in the femoral arterial pulse pressure, which reduced from 36±1 mmHg during the control period to 23±1 mmHg during the HS period (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Renal perfusion pressure (RPP) in servo-controlled (A) (n=12) and sham (B) (n=17) rats during 3-days 0.4% NaCl and 7-days 4.0% NaCl intake. The carotid arterial pressure (grey) represents pressure to the right kidney, whereas the femoral arterial pressure (black) represents pressure to the left kidney. Data are presented as Means ± SEM for 24hr averages of the day of study. Renal immune cell infiltration in servo-controlled (C) (n=12) and sham (D) (n=17) rats after 7-days of 4.0% NaCl intake. Left kidney (black bars) and right (grey bars) are shown. CD3+ (mature T-cells), CD3+CD4+ (helper T-cells), CD3+CD8+ (cytotoxic T-cells), CD45R+ (B-Cells), CD11b/c+ (monocytes and macrophages). Data are presented as Means ± SEM and expressed as total cells per kidney. #=significantly different from the average blood pressure measurement during the control period, #=p<0.05, ###=p<0.001. *=significantly different from the left kidney in the same group on the same study day, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.005, ***=p<0.001.

In sham rats RPP to both kidneys increased throughout the 4.0% HS challenge. RPP was significantly higher than control values from HS-1 onwards in the left kidneys and HS-2 in the right kidneys (Figure 1B). Notably, at HS day-7 RPP to the right kidneys of sham rats (154±2 mmHg) was comparable to that of the right hypertensive kidneys of the servo-controlled rats (157±4 mmHg).

Increased renal perfusion pressure augments immune cell infiltration into the kidney

Figure 1C shows lymphocyte infiltration into the left and right kidneys of servo-controlled rats. Lymphocyte infiltration was significantly higher in the uncontrolled-hypertensive right kidneys than in the servo-controlled left kidneys. Levels of all T-cells (CD3+), as well as subsets of helper (CD3+CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD3+CD8+) T-cells were all significantly higher in the uncontrolled hypertensive right kidneys than in the pressure-controlled left kidneys (p<0.001). CD45R+ B-cell infiltration was also significantly higher in the hypertensive kidney than in the servo-controlled kidney. Notably, the absolute number of B-cells in the hypertensive kidneys was 4x lower than the absolute number of CD3+ T-cells, Table 1.

Table 1.

Cells per kidney presented as Means ± SEM.

| Kidney | CD3+ | CD3+CD4+ | CD3+CD8+ | CD45R+ | CD11b/c+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servo Left | 77,726±12,125 | 31,594±5,647 | 42,356±7,063 | 12,986±2,395 | 622,458±128,082 |

| Servo Right | 168,084±24,112*** | 76,031±12,286*** | 88,211±13,457*** | 39,318±7,889** | 1,201,044±281,223* |

| Sham Left | 186,360±47,154 | 86,403±26,629 | 102,082±22,467 | 34,520±6,564 | 1,487,710±360,823 |

| Sham Right | 194,359±26,359 | 93,989±15,546 | 104,686±12,840 | 50,673±10,894 | 1,855,324±449,982 |

| Reversal Left | 419,347±77,336†† | 177,494±43,299† | 266,119±45,407†† | 33,113±8,818 | 2,544,088±576,550 |

| Reversal Right | 544,449±88,671 | 229,963±47,601 | 344,397±54,566 | 65,496±18,448* | 3,516,343±613,422 |

significantly different from the left kidney in the same group.

p<0.05,

p<0.005,

p<0.001.

significantly different between the left reversal and the left sham kidney.

p<0.05,

p<0.005.

In contrast, there was no significant difference in T-cell infiltration in the left and right kidneys of sham rats, which were exposed to comparable RPPs throughout the salt challenge (Figure 1D). The abundance of CD3+ T-cells per kidney in the left and right kidneys of sham rats were comparable to the number of CD3+ T-cells in the hypertensive right kidneys of the servo-controlled rats (Table 1). The same was true for the abundances of CD3+CD4+ (Figure 1D) and CD3+CD8+ (Figure 1D) T-cells per kidney, which were also not significantly different between the left and right kidneys of sham rats. Again, the absolute abundance of B-cells in the hypertensive kidneys was 4x lower than that of CD3+ T-cells.

The protective effect of preventing hypertension was not specific to renal lymphocyte infiltration since there were significantly fewer CD11b/c+ (monocytes and macrophages) cells in the servo-controlled left kidneys relative to the hypertensive-right kidneys of the servo-controlled rats (Table 1). In contrast there was no significant difference in the number of CD11b/c+ cells in the left and right kidneys of the sham rats (p=0.378) (Table 1).

Renal norepinephrine levels are equivalent in the left and right kidneys of surgically prepared rats

Previous studies have implicated sympathetic activity in the initiation of renal T-cell infiltration and the development of hypertension19. To eliminate the possibility that the chronic servo-control protocol inadvertently caused renal denervation we measured norepinephrine levels in the left and right kidneys of five sham rats. In three of the rats we also measured immune cell infiltration. Norepinephrine levels were not significantly different between the left (93.2±18.3 pg/mg) and right kidneys (128.7±33.1 pg/mg) (p=0.410) suggesting that neither the surgical preparation nor occluder damaged renal innervation.

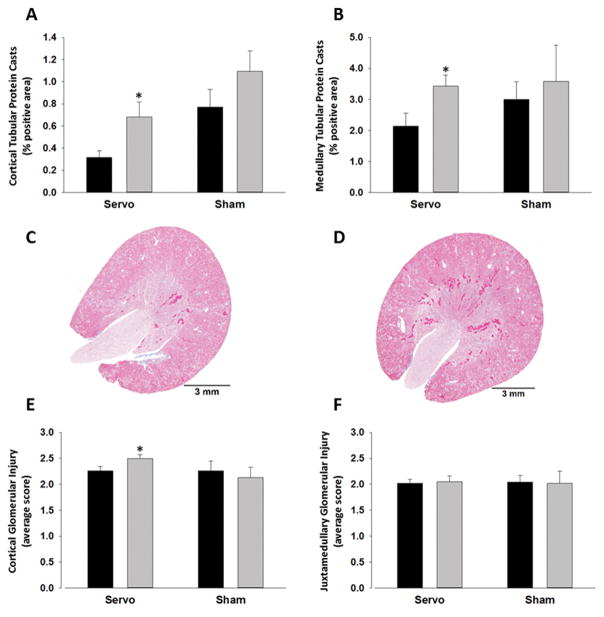

Increased renal perfusion pressure is associated with increased renal injury in SS rats

Renal histological analysis is illustrated in Figure 2. Trichrome staining was used for the quantification of tubular protein casts and glomerular injury in the cortex and medulla of left and right kidneys isolated from six servo-controlled and six sham rats. There were significantly more tubular protein casts in both the cortex and medulla of the hypertensive-right kidneys of servo-controlled rats compared to the pressure controlled-left kidneys (Figure 2A–D). Similarly, cortical glomerular injury was significantly higher in the right-hypertensive kidneys compared to the left-controlled kidneys (Figure 2E+S2). In contrast there was no difference in the degree of glomerular scarring injury observed in the juxtamedullary border region (Figure 2F). We found no difference in the degree of renal injury observed in the left and right kidneys of sham rats, both of which were exposed to uncontrolled pressures throughout the study (Figure 2A, B, E and F). Given the involvement of T-cells in renal fibrogenesis20,21 we assessed mRNA abundance of collagen and smooth muscle actin in the servo-control kidneys (Figure 3A+B). As shown in (Figure 3B) renal fibrosis markers were all significantly higher in the medulla of the hypertensive-right kidneys relative to the servo-controlled left medullas. In contrast, although there was a trend towards increased fibrosis markers in the cortex this only reached significance for Col1a1 (Figure 3A). Flow cytometry does not give spatial localization of T-cell infiltration; therefore, histological slices were stained with CD3+ antibodies. Through qualitative examination we see dispersed infiltration throughout the kidney. Figure 3C+D show regions of high T-cell accumulation in the cortex and medulla respectively indicating that increased T-cell infiltration is not due exclusively to accumulation in one compartment of the kidney.

Figure 2.

Renal injury in servo-controlled and sham rats. Left kidneys (black bars) are compared to the corresponding right kidneys (grey bars). Tubular protein casts in the cortex (A) and medulla (B) was quantified as the % of the total area which were casts. Example images of left (C) and right (D) kidneys from servo-controlled rats are shown. Glomerular injury was quantified in the cortex (E) and juxtamedullary region (F) by scoring glomeruli on a scale of 0–4. 4 represents the most severe damage. Data are presented as Means ± SEM. *=p<0.05 compared to the left kidney within the same group.

Figure 3.

qPCR assessment of genes involved in renal fibrosis in the cortex (A) and medulla (B) of right-hypertensive (grey) and left servo-controlled (black) kidneys (n=8). *=significantly different from the left kidney on the same day of study, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. CD3+ staining in the cortex (C) and medulla (D) is represented by the brown staining.

The hypertensive kidneys of the servo-controlled rats were marginally heavier than the controlled-left kidneys (2.1±0.1 g vs. 1.9±0.1 g respectively, p<0.05). However, since the weights were comparable to the kidneys of the sham rats, both of which weighed 2.0±0.1 g, we would not expect this to account for the difference in immune cell infiltration.

7-days reversal of hypertension does not return renal T-cell infiltration to control levels in SS rats

To assess the reversibility of renal immune cell infiltration we used the chronic servo-control system to bring RPP to the left kidney back to control levels following 7-days exposure to salt-sensitive hypertension. Following 7-days of HS, RPP to the left kidney averaged 136±2.1 mmHg, at this point the servo-control system was used to bring the pressure back to a level comparable to the average control level of 122±1.2 mmHg (Figure 4A). Notably, during this reversal period the rats continued to eat a 4.0% NaCl HS diet. There was a tendency for reversal of RPP to blunt total renal leukocyte infiltration (left-reversal: 3,115,406±666,398 vs. right-hypertensive: 4,291,801±726,003 CD45+ cells per kidney) however, this did not reach significance (p=0.09).

Figure 4.

Renal perfusion pressure (RPP) (A) and lymphocyte infiltration (B) in servo-controlled reversal study. The carotid artery pressure (grey) represents pressure to the right kidney (n=6, two catheters did not work), whereas the femoral artery pressure (black) represents pressure to the left, servo-controlled reversal kidney (n=8). Data are presented as Means ± SEM for 24hr averages of the day of study (A). Left reversal kidneys (black) and right hypertensive kidneys (grey) (B). #=significantly different from the average blood pressure measurement during the 3-days of the control period, ##=p<0.005, ###=p<0.001. *=significantly different from the left kidney on the same day of study, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

The number of CD3+, CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T-cells were all significantly higher in the left-reversal kidney than in the left sham kidneys from our first study, which were also exposed to 7-days of salt-sensitive hypertension (Table 1). Furthermore, although there was a trend for reduced T-cell infiltration in the left-reversal kidney, we found no significant difference from the right-hypertensive kidneys of the reversal rats (Figure 4B). Together, these data indicate that 7-days of reversal of pressure alone is not sufficient to either stop or reverse renal T-cell infiltration. In contrast, we found no significant differences in the number of CD45R+ B-cells in the left kidneys of sham and reversal rats (Table 1) and there were significantly fewer B-cells in the left-reversal kidney than in the right-hypertensive kidney of reversal rat (Figure 4B). This suggests that reversal of pressure did stop further significant increases in B-cell infiltration.

Histological analysis found that reversal of pressure did not reduce the formation of tubular protein casts. (Medullary protein casts: right-hypertensive kidneys 1.7±0.6 vs. left-reversal kidneys 2.0±0.6 % positive area p=0.6, cortical protein casts: right-hypertensive kidneys 0.3±0.2 vs. left-reversal kidneys 0.8±0.4 % positive area p=0.2, n=6). We also found no difference in glomerular injury scores in the left-reversal and right hypertensive kidneys (Juxtamedullary: right-hypertensive kidneys 2.9±1.2 vs. left-reversal kidneys 2.4±1.0 p=0.4, cortical: right-hypertensive kidneys 2.7±1.0 vs. left-reversal kidneys 2.2±0.8 p=0.6)

Discussion

Increased renal T-cell infiltration is a cardinal feature of salt-induced hypertension in the SS rat. Attenuation of renal T-cell infiltration blunts the hypertensive response to 21-days high salt diet and improves renal structure11–14. The present study utilized the unique servo-control protocol to address the role of elevated RPP in the initiation of renal T-cell infiltration in SS rats. The aim of these studies was to determine whether immune cell infiltration is a primary cause or secondary consequence of the hypertensive response to a HS diet in SS rats.

Of note, a recent study used a combination of anti-hypertensive agents to discern the role of pressure in renal immune cell infiltration in AngII dependent hypertension in mice22. This study suggested that the attenuation of hypertension prevented T-cell infiltration into the kidneys of AngII infused mice indicating that increased pressure was involved in the initiation of renal inflammation of that model. However, use of anti-hypertensive agents to control RPP can result in off target and secondary drug effects which could in themselves alter T-cell infiltration and/or activation and confound the interpretation of these results. Here, to address this question in SS rats, we used our unique servo-control system which allows us to more definitively study the effects increased RPP in isolation. Importantly, this technique provides paired analysis of the kidneys within the same animal exposed to different perfusion pressures but with both kidneys exposed to the same hormonal milieus and the secondary effects of a high-salt intake throughout the study. Norepinephrine levels were comparable in the left and right kidneys suggestive of equal sympathetic drive. Therefore, in these studies any observed changes in immune cell infiltration are a direct consequence of differences in RPP. The data presented show that renal immune cell infiltration occurs in response to elevated RPP in SS rats. Following 7-days HS diet there was a significantly higher abundance of T-cells, B-cells and monocytes and macrophages in the hypertensive-uncontrolled right kidney compared to the servo-controlled left kidney of the servo-control rats. In previous servo-control studies, in which SS rats were maintained on a HS diet for 14-days, it was found that there was increased ED-1 positive macrophage accumulation around glomerular tufts in the hypertensive kidney relative to the servo-controlled kidney, in agreement with the findings of our current study. Interestingly, in this earlier study the results from the servo-controlled kidney were compared to those of a sham-rat maintained on a control salt diet. This allowed the effects of salt, independent of pressure, to be discerned. It was found that ED-1 staining, glomerular injury and tubular protein casts were equivalent in the servo-controlled kidney and a control-salt sham kidney. These data suggest that increased salt intake, in the absence of increased pressure, is not sufficient to induce macrophage infiltration and renal injury. Therefore, we postulate that in the current study the T-cell accumulation observed in the servo-controlled kidney would be comparable to that of a sham rat maintained on a control salt.

The signaling pathway by which increased RPP drives renal immune cell infiltration has not been determined and is beyond the scope of this study. However, in our previous servo-control study in SS rats microarray analysis was used to determine which genes are differently expressed in the hypertensive kidney. After 14-days of HS several genes implicated in inflammation were significantly higher in the hypertensive kidney than in the servo-controlled kidney. These included: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule 1, macrophage galactose N-acetyl-galactosamine specific lectin, matrix metalloproteinase 2 and complement component 4. Whether these genes are involved in the initiation of renal inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension is an interesting area of future research. Increased immune cell infiltration was associated with increased renal injury, characterized by tubular protein casts, increased abundance of genes involved in renal fibrosis and glomerular damage, in the hypertensive kidneys of servo-controlled rats. We saw dispersed T-cell infiltration using CD3+ immunohistochemistry, however unlike flow-cytometry, which gives a holistic view of the entire tissue, histological assessment represents only one slice and therefore provides insufficient data to quantify infiltration.

We interpret the present data to indicate that a primary defect in the SS rat leads to an initial increase in blood pressure with high salt feeding and that increased blood pressure, by a mechanism not yet described, mediates the infiltration of immune cells into the kidney. As we have previously demonstrated, the infiltrating immune cells then serve to amplify the salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage13,14.

Despite the clear role of RPP in the initiation of renal T-cell infiltration, 7-days reversal of pressure alone did not blunt this aspect of the inflammatory response. Although there was a trend towards reduced T-cells in the reversal-left kidney relative to the hypertensive-right kidney this did not reach significance. It is possible that a longer reversal period is required to return renal T-cell infiltration to control levels. However, it is not technically feasible to extend this time-course much beyond a period of 7-days. Since these studies selectively reverse RPP (the rats are maintained on 4.0% NaCl throughout), this may suggest a role for increased dietary salt in the amplification and maintenance of renal T-cells abundance, following the initiation of infiltration. In line with this observation, several recent studies have implicated salt in the activation of immune cells and the promotion of pro-inflammatory responses21,23–26. Interestingly, in this study the 7-day HS pressure in the SS rats was substantially lower that observed in our first experiment. This reflects the inter-experimental variability of the SS rat. Nevertheless, we still observed a substantial infiltration of renal immune cells. We interpret these data to suggest that, either there is a pressure threshold, which once surpassed, initiates renal inflammation or it is the magnitude of change in pressure, rather than the absolute pressure, that is important for the initiation of renal inflammation. Despite the blunted pressor response to HS in the SS rats used in the reversal experiments, the absolute number of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney at the end of the experiment was substantially higher. This may reflect a “two hit” inflammatory response, whereby increased pressure initiates the infiltration of immune cells and a HS diet perpetuates the response. However, given the variability of flow-cytometry data, further experiments would be needed to test this hypothesis.

Although we have shown that renal T-cell infiltration is augmented by hypertension, the data presented do not preclude a role for T-cells in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension in SS rats; rather they implicate the immune system in the secondary stages of the disease.

Perspectives

Renal infiltration of immune cells has been described in both clinical and experimental hypertension. In this study we have used a chronic servo-control technique to identify the role of RPP in renal immune cell infiltration in SS rats. We found that renal immune cell infiltration was significantly higher in the hypertensive right kidney than in the servo-controlled left kidney. We interpret these data to indicate that infiltration of immune cells into the kidney occurs in response to an initial increase in pressure. As we have previously shown13,14, the immune cells then amplify the salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

1. What is new?

These studies are the first to use a chronic servo control technique to determine the role of renal perfusion pressure to renal T-cell infiltration in SS rats. The use of this unique technique has allowed us to separate the effects of pressure from those of circulating factors and sympathetic activity.

2. What is Relevant?

The SS rat is a model of clinical salt-sensitive hypertension. This study suggests that targeting the immune system may be a way to delay the progression of an initial hypertensive response to malignancy.

3. Summary

Renal inflammation is a cardinal feature of salt-sensitive hypertension in SS rats. Using a chronic servo control technique we have shown that augmented renal perfusion pressure increases renal T-cell infiltration in SS rats. Augmented T-cell infiltration in the hypertensive right kidney relative to the servo-controlled left kidney occurred despite exposure to the same circulating factors and equivalent sympathetic drive.

Acknowledgments

We thank Glenn Slocum and Robert Ryan for assistance with microscopy and image analysis and Lisa Henderson for the measurement of renal norepinephrine levels.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by HL-116264 and DK-96859 (LCE, GP, TK, DLM and AWC). LCE was funded by an AHA postdoctoral fellowship grant (AHA13POST15230000). JDB was funded by an AHA predoctoral fellowship grant (AHA16PRE29700006).

Footnotes

Parts of this work were presented as an abstract at the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension Scientific Session 2015 and 2016.

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Hughson MD, Gobe GC, Hoy WE, Manning RD, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF. Associations of glomerular number and birth weight with clinicopathological features of African Americans and whites. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;52:18–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattson DL. Infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;307:F499–F508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00258.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertensive end-organ damage. Circ Res. 2015;116:1022–1033. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozawa Y, Kobori H, Suzaki Y, Navar LG. Sustained renal interstitial macrophage infiltration following chronic angiotensin II infusions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F330–339. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00059.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:263–270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowley AW, Jr, Ryan RP, Kurth T, Skelton MM, Schock-Kusch D, Gretz N. Progression of glomerular filtration rate reduction determined in conscious Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2013;62:85–90. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato N. Genetic analysis in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:539–540. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng S, Cason GW, Gannon AW, Racusen LC, Manning RD., Jr Oxidative stress in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:1346–1352. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000070028.99408.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor NE, Cowley AW., Jr Effect of renal medullary H2O2 on salt-induced hypertension and renal injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1573–1579. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00525.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Miguel C, Das S, Lund H, Mattson DL. T lymphocytes mediate hypertension and kidney damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1136–1142. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00298.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Miguel C, Guo C, Lund H, Feng D, Mattson DL. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and participate in the development of hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F734–742. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00454.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudemiller N, Lund H, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Mattson DL. CD247 modulates blood pressure by altering T-lymphocyte infiltration in the kidney. Hypertension. 2014;63:559–564. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudemiller NP, Lund H, Priestley JR, Endres BT, Prokop JW, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Cohen EP, Mattson DL. Mutation of SH2B3 (LNK), a genome-wide association study candidate for hypertension, attenuates Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension via inflammatory modulation. Hypertension. 2015;65:1111–1117. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattson DL, Lund H, Guo C, Rudemiller N, Geurts AM, Jacob H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R407–414. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00304.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori T, Polichnowski A, Glocka P, Kaldunski M, Ohsaki Y, Liang M, Cowley AW., Jr High perfusion pressure accelerates renal injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1472–1482. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori T, Cowley AW., Jr Role of pressure in angiotensin II-induced renal injury: chronic servo-control of renal perfusion pressure in rats. Hypertension. 2004;43:752–759. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000120971.49659.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polichnowski AJ, Lu L, Cowley AW., Jr Renal injury in angiotensin II+L-NAME-induced hypertensive rats is independent of elevated blood pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F1008–1016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00354.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao L, Kirabo A, Wu J, Saleh MA, Zhu L, Wang F, Takahashi T, Loperena R, Foss JD, Mernaugh RL, Chen W, Roberts J, 2nd, Osborn JW, Itani HA, Harrison DG. Renal Denervation Prevents Immune Cell Activation and Renal Inflammation in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117:547–557. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tapmeier TT, Fearn A, Brown K, Chowdhury P, Sacks SH, Sheerin NS, Wong W. Pivotal role of CD4+ T cells in renal fibrosis following ureteric obstruction. Kidney Int. 2010;78:351–362. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehrotra P, Patel JB, Ivancic CM, Collett JA, Basile DP. Th-17 cell activation in response to high salt following acute kidney injury is associated with progressive fibrosis and attenuated by AT-1R antagonism. Kidney Int. 2015;88:776–784. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itani HA, McMaster WG, Jr, Saleh MA, et al. Activation of Human T Cells in Hypertension: Studies of Humanized Mice and Hypertensive Humans. Hypertension. 2016;68:123–132. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang WC, Zheng XJ, Du LJ, et al. High salt primes a specific activation state of macrophages, M(Na) Cell Res. 2015;25:893–910. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN, Hafler DA. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature. 2013;496:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, Zhu C, Xiao S, Kishi Y, Regev A, Kuchroo VK. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature. 2013;496:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binger KJ, Gebhardt M, Heinig M, et al. High salt reduces the activation of IL-4- and IL-13-stimulated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4223–4238. doi: 10.1172/JCI80919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.