Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors often experience joint pain as a side effect of their treatment; qualitative investigations suggest that this arthralgia may cause women to feel they are aging faster than they should be. To facilitate further study of this experience, the Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale (PAAS) was developed. This report describes the development and validation of the PAAS in a racially diverse sample of breast cancer survivors suffering from joint pain.

Patients and Methods

Items of the scale were developed from a content analysis of interviews with patients. The scale was pilot-tested and modifications were made based on patient feedback. Subsequently, 556 breast cancer survivors who endorsed joint pain completed the eight-item PAAS. Factor structure (using exploratory factor analysis), internal consistency, and convergent, divergent, and incremental validity were examined.

Results

The resulting scale had a one-factor structure with strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.94), and demonstrated both convergent and divergent validity: The PAAS was significantly correlated with joint pain severity (r = .55, p < 0.01) and had a small and non-significant correlation with actual age (r = −0.07, p = 0.10). The PAAS was also found to predict incremental variance in anxiety, depression, and pain interference outcomes.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the PAAS produced reliable and valid scores that capture perceptions of aging due to arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. With further research, the PAAS may advance our understanding of how perceptions of aging may affect breast cancer survivors’ emotional, behavioral and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: arthralgia, aromatase inhibitors, breast neoplasms, psychometrics, perceptions of aging

Introduction

In 2013, approximately 235,000 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in the United States.1 Aromatase inhibitors (AIs), an oral adjuvant hormonal therapy for post-menopausal women, have been shown to decrease the recurrence rate and increase the overall survival rate of hormone receptor positive breast cancer,2,3 the most common type of breast cancer, comprising about 80% of all cases among menopausal women.4 Unfortunately, AIs often come with difficult side effects, of which AI-associated arthralgia (AIAA) is one of the most common.5

For many women, joint pain and stiffness may be too overwhelming to manage. Though options for relieving AIAA exist (including switching to a different AI, taking a drug holiday, pursuing pharmacological treatment, and/or starting an exercise regimen6), some women do not benefit from or try these strategies and therefore discontinue their AIs. Examining 437 women on AIs, Chim and colleagues found that high levels of joint pain predicted premature discontinuation of AIs7; moreover, in a clinical trial comparing two AIs, 24.3% of enrolled women who discontinued their medication cited musculoskeletal symptoms as the reason.8 As premature discontinuation has been linked to increased rates of recurrence and mortality,9 it is crucial to understand AI patients’ experience of AIAA.

Qualitative investigations and case studies reveal that arthralgia experienced while on AIs makes some breast cancer survivors feel that they are aging faster than they should be.10–12 As one woman succinctly put it, “I feel like I am 100 years old!”12 For some, the sense of aging caused by their arthralgia contributes to a feeling that time is “fleeting” and that their health is compromised.10 General self-perceptions of aging (outside the context of joint pain) have been shown to predict mortality, health behaviors, and physical functioning in longitudinal studies,13–15 suggesting that that arthralgia-associated aging perceptions may also be related to behavioral outcomes among AI users and could prove to be a fruitful target for adherence interventions.

No effort has yet been made to systematically measure and quantify self-perceptions of aging related to joint pain. A reliable and valid measure would allow further study of arthralgia-associated aging perceptions and facilitate investigation of its impact on breast cancer survivors’ wellbeing, health behaviors, and clinical outcomes. To address this need, this study describes the development of the Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale (PAAS) and its validation among a racially diverse sample of breast cancer survivors suffering from joint pain.

Methods

Participants

Data for this particular study were drawn from the baseline assessment of 853 participants of an ongoing longitudinal study examining genetic determinants of symptom distress and disease outcomes among postmenopausal women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer who had been prescribed AIs16,17 and were consented between November, 2011 and September, 2013. Analysis focused on participants who endorsed joint pain (as demonstrated by a score of 1 or higher [out of 10] when asked to assess their pain at its worst in the past 7 days) and excluded those who had not completed all items of the PAAS (n = 58), leaving a sample size of 596 for this study.

Research assistants recruited participants from breast cancer clinics in an academic tertiary care teaching hospital and a community hospital. Eligibility criteria for the main study were (1) female sex; (2) age 18 or older; (3) history of stage I, II, or III breast cancer; (4) current use of a third-generation AI for at least 6 months or discontinuation of AIs before the full duration of prescribed therapy; (5) postmenopausal; (6) completed primary cancer treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy); and (7) able to understand written English and participate in an informed consent process. Before approaching potential participants at medical appointments, research assistants screened their medical records to ensure they met the study’s eligibility criteria. After providing informed consent, participants completed a self-administered survey in the breast cancer clinic. All measures and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Measures

Penn Arthalgia Aging Scale

We developed items in the PAAS by conducting a content analysis of interviews with 67 breast cancer patients on AIs participating in an acupuncture clinical trial for joint pain.18 A team of two medical oncologists, two physical therapists, and two oncology nurses reviewed the items for their face validity. The scale was subsequently pilot-tested on 12 female breast cancer survivors on AIs who had arthralgia and who were not part of this study. We then clarified item wording based on patient feedback. The final version of the PAAS consists of eight items which ask patients to consider how their joint pain in the past seven days has affected how they feel about their “bodies and states of mind.” Each item consists of a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (completely). Ratings from all items are added together to create a PAAS total score, ranging from 0 to 32. Higher scores indicate more intense perceptions of arthralgia-associated aging.

Measures to assess convergent and divergent validity

We expected greater perceptions of aging among those with more severe joint pain; therefore, the Pain Intensity subscale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) was used to assess the convergent validity of the PAAS. To demonstrate divergent validity, we expected this correlation to be significantly greater than the correlation between the PAAS and the patient’s actual age because the PAAS is intended to reflect psychological perceptions of aging due to joint pain, not the actual passing of time.

Measures to assess incremental validity

To determine whether the PAAS increases our understanding of patients’ experience beyond existing measures, the incremental validity of the PAAS for predicting psychological outcomes and pain interference was assessed. It is well established that chronic pain is associated with depression and anxiety19,20 and that pain, depression, and anxiety impact daily functioning.21–23 If the PAAS accounts for significant variance in depression and anxiety over and above the effects of pain intensity, and predicts the degree to which pain interferes with daily functioning over and above the effects of pain intensity, depression and anxiety, this will further support the importance of the aging perceptions construct and the incremental validity of the scale. Consequently, the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS24) and the Pain Interference Scale of the BPI25 were used. In this sample, the Cronbach’s alphas for the anxiety, depression, and pain interference subscales were 0.84, 0.83, and 0.94, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Exploratory factor analysis of the PAAS using a geomin (oblique) rotation was completed in MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). A weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) adjusted estimator was used because traditional maximum likelihood estimators can yield biased estimates with ordinal scales, such as the PAAS.26 To determine the number of factors, the Kaiser criterion was applied and a scree plot was examined, along with factor loadings and fit indices (the comparative fit index [CFI] and the standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]27), for possible solutions.1

Nonparametric correlations (Spearman r [rs]) were calculated to assess convergent and divergent validity. These correlations were compared using the procedure developed by Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin28 for contrasting correlated correlation coefficients. To assess incremental validity, three hierarchical regressions were conducted to determine whether the PAAS predicted incremental variance in anxiety, depression, and pain interference outcomes. When anxiety and depression were the dependent variables, pain severity and age were simultaneously entered in Step 1, and the PAAS was entered in Step 2. When pain interference was the outcome, pain intensity, age, depression, and anxiety were entered into Step 1, and the PAAS was entered in Step 2. All variables, except age, were transformed to normalize their distribution for regression analyses.

Results

Demographics

The average age of participants was 64 years old (SD = 9.8). Whites constituted the majority of the sample (83.6%), followed by African Americans (14.9%). About a third of the sample was engaged in full-time employment, and about two thirds (61.2%) were married or cohabitating with a partner (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and AI Status (N =596)

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean | 64.0 yrs |

| SD | 9.8 yrs | |

| Race | White | 498 (83.6%) |

| African American | 89 (14.9%) | |

| Asian | 4 (0.7%) | |

| More than one race | 5 (0.8%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 57 (9.6%) |

| Married or Cohabitating | 365 (61.2%) | |

| Divorced | 78 (13.1%) | |

| Separated | 9 (1.5%) | |

| Widowed | 87 (14.6%) | |

| Education level | High school diploma or less | 117 (19.6%) |

| Some college or trade school | 135 (22.7%) | |

| 4-year college | 134 (22.5%) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 210 (35.2%) | |

| Employment status | Employed full-time | 195 (32.7%) |

| Employed part-time | 82 (13.8%) | |

| Not currently employed | 319 (53.5%) | |

| Current AI Status | Taken an AI in the last month | 401 (67.3%) |

| Not taken an AI in the last month | 195 (32.7%) |

Note. AI = aromatase inhibitor; SD = standard deviation.

Missing Data

Only participants who had completed all items on the PAAS were included in this study. No differences were found in age, marital status, education, employment, or race between those who had completed the PAAS and those who left some or all PAAS items blank. Of those who had complete data for the PAAS, four participants had missing data on other measures (HADS, BPI) used in the validation analyses. Because no more than 20% of items on any of these measures were missing, we conducted mean imputation to calculate total scores for these cases.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Examination of the Kaiser criterion and scree plot indicated a one-factor solution. Model fit was excellent (CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.09) and factor loadings for all items were above 0.82. Internal consistency of the scale was very strong (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). Factor loadings and item-remainder correlations for each item can be found in Table 2. Item responses showed that a substantial portion of participants endorsed high levels of aging perceptions. For example, 20.7% of respondents agreed strongly (defined as selecting a 3 or 4 on the Likert scale) with the statement, “I feel that I have aged many years in a short period of time.” Approximately 15% of respondents strongly endorsed “I feel older than people my age.”

Table 2.

Geomin-Rotated Factor Loadings and Distribution of Item Responses for Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale (PAAS)

| PAAS Item | Factor Loading | Item-remainder r | Mean (SD) | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I have slowed down quite a bit. | 0.87 | 0.78 | 1.38 (1.14) | 1.00 |

| 2. I am not as active as I used to be. | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.53 (1.23) | 1.00 |

| 3. I have had to stop doing some of the things I used to enjoy. | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.27 (1.24) | 1.00 |

| 4. I am hesitant to try new activities. | 0.82 | 0.75 | 1.17 (1.18) | 1.00 |

| 5. I cannot easily do things that others my age are able to do. | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.12 (1.17) | 1.00 |

| 6. I feel older than people my age. | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.91 (1.24) | 0.00 |

| 7. I feel that I have aged many years in a short period of time. | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.20 (1.33) | 1.00 |

| 8. I am trapped in a body that seems much older than my current age. | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.95 (1.26) | 0.00 |

Note. PAAS = Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale; SD = standard deviation.

Convergent, Divergent, and Incremental Validity

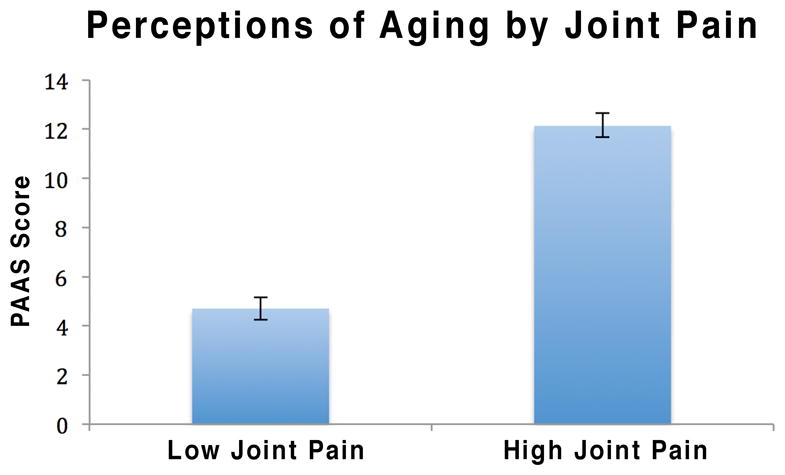

A large, positive correlation was found between the PAAS and joint pain intensity (r = 0.55, p < 0.01), providing evidence for the convergent validity of the PAAS. Women who endorsed low levels of joint pain (1–3 on Item 1 of the pain intensity scale of the BPI) scored an average of 4.70 on the PAAS, whereas women with high levels of joint pain (4 or higher) scored an average of 12.13 on the PAAS (Figure 1). In contrast, the correlation between the PAAS and actual age was negligible (see Table 3). The size difference between these correlations was statistically significant (z = 11.60, p < .001), which indicates the scale has divergent validity.

Figure 1.

Average Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale scores among high joint pain and low joint pain subjects. Pain level was assessed with the Pain Intensity subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory. Bars represent standard error.

Table 3.

Spearman Rho Correlations of the Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale and Pain, Mood, and Pain Interference Variables

| Measure | Mean (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PAAS | 9.55 (8.27) | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2. BPI - Pain Intensity | 13.28 (8.33) | 0.55** | 1.00 | |||||

| 3. BPI - Pain Interference | 17.42 (16.58) | 0.74** | 0.75** | 1.00 | ||||

| 4. HADS -Depression HADS | 4.01 (3.36) | 0.68** | 0.34** | 0.54** | 1.00 | |||

| 5. HADS -Anxiety | 6.32 (3.85) | 0.34** | 0.20** | 0.29** | 0.53** | 1.00 | ||

| 6. Age | 63.81 (9.75) | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −.07 | −.18** | 1.00 | |

| 7. AI status | NA | 0.02 | −0.01 | −.06 | −0.10* | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Note. AI = aromatase inhibitor; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NA = not applicable; PAAS = Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale; SD = standard deviation.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

All three hierarchical regressions demonstrated the significant incremental validity of the PAAS (Table 4): The PAAS explained an additional 28% (large effect) in variance for depression and an additional 7% (small effect) in variance for anxiety, above and beyond pain intensity and age (see Tables 4). The PAAS also explained an additional 5% of variance (small effect) in pain interference, above and beyond depression, anxiety, pain intensity, and age. Because a few items on the PAAS have similar content to the pain interference scale (Items 2 and 3), the hierarchical regression was repeated with an abbreviated version of the PAAS that excluded these items. This did not change the incremental variance explained by the PAAS (5%, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that the PAAS captures an important and unique construct that is not already captured by measures typically associated with emotional and functional outcomes.

Table 4.

Summary of Hierarchical Regressions for Testing the Incremental Validity of the PAAS

| Independent variables | Betaa | R2 | R2 change | F change | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure: HADS depression subscaleb | ||||||

| Step 1 | BPI – Pain Intensityc | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 40.0 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.07 | |||||

| Step 2 | PAASc | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 277.0 | <0.001 |

| Outcome measure: HADS anxiety subscaleb | ||||||

| Step 1 | BPI – Pain Intensityc | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 23.41 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.21 | |||||

| Step 2 | PAASc | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 47.00 | <0.001 |

| Outcome measure: BPI pain interference subscaleb | ||||||

| Step 1 | BPI – Pain Intensityc | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 268.64 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.02 | |||||

| HADS - Anxietyb | 0.00 | |||||

| HADS - Depressionb | 0.35 | |||||

| Step 2 | PAASc | 0.32 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 98.24 | <0.001 |

Note. PAAS = Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Betas reported are those from the step at which the variable was entered.

Square-root transformed.

Log-transformed.

Discussion

With the input of both patients and providers, the PAAS was developed to capture perceptions of aging among breast cancer survivors suffering from joint pain. Results suggest that the measure has strong psychometric properties and captures a meaningful construct: The PAAS has excellent internal consistency and, as predicted, correlates strongly with joint pain. Additionally, the scale’s divergent validity, as shown by its non-significant association with actual age, further highlights the importance of the PAAS construct by demonstrating that actual age is not a useful proxy for understanding a women’s psychological experience of aging in the context of cancer survivorship.

The strongest evidence for the measure’s importance is its incremental validity in explaining emotional and functional outcomes. The PAAS was able to explain additional variance in depression and anxiety over and above pain severity. After depression, anxiety, and pain severity were controlled, the PAAS was also able to explain additional variance in pain interference. In sum, how women with joint pain perceive the aging of their bodies can provide unique insights into important aspects of their wellbeing that are not explained by other constructs.

Arthralgia-associated perceptions of aging may also provide insight into the causal chain that connects joint pain symptoms to lower AI adherence.7 As findings in this study suggest, joint pain may lead to higher perceptions of aging, which in turn may contribute to depression. As meta-analytic work has shown that depression and non-adherence are related,29 higher levels of depression may then ultimately lead to lower AI adherence. Considering the high rate of non-adherence and discontinuation of AIs,30,31 this mediation hypothesis is worth further exploration.

It would also be useful to explore whether aging perceptions impact other health behaviors such as physical activity. Remaining physically active is essential to optimizing long-term health outcomes among breast cancer survivors,32 and joint pain among women on AIs has been found to be associated with reduced physical activity.33 As aging perceptions are related to pain interference, the PAAS may further explain some of the variation in physical activity levels among women on AIs and provide guidance on how to design psychological interventions to increase exercise.

Limitations

This study was cross-sectional, and test-retest reliability of the PAAS was not evaluated. It is also unclear whether the PAAS is sufficiently sensitive to assess change in arthralgia-associated aging perceptions over time. The predictive validity of the PAAS was not explored; evidence that arthralgia-associated perceptions of aging predict changes in functional outcomes and health behaviors (e.g., AI medication adherence, physical activity) would strengthen support for the scale’s significance. Furthermore, given the high internal consistency of the PAAS (> 0.90), it is possible that some items are redundant and a shorter version may be used if so desired.34 Lastly, because this instrument was validated among breast cancer survivors, it is unclear how generalizable these findings are to other populations experiencing joint pain.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that breast cancer survivors with higher levels of joint pain are more likely to carry negative beliefs about how their joint pain has impacted their aging process. These beliefs may lead to impaired wellbeing that cannot be explained by pain intensity alone. To our knowledge, the PAAS is the first reliable and valid instrument to quantitatively assess these beliefs. Using this scale, observational studies can be conducted to define the temporal relationship between this psychological experience and important health behaviors such as adherence and physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Subsequently, intervention studies can be developed which target arthralgia-associated aging perceptions by using approaches such as cognitive-behavioral restructuring, mindfulness, or acceptance and commitment therapy. Ultimately, by providing interventions that effectively address the psychological experience of aging due to joint pain, we can potentially improve clinical outcomes and quality of life for women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute; R01 CA158243. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

It would have been preferable to use parallel analysis to determine the number of factors, but such analysis is not possible for WLSMV estimation in Mplus.

Results of this study demonstrate the psychometric validity of the Penn Arthralgia Aging Scale among breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. This scale captures women’s perceptions of aging due to arthralgia and was found to predict incremental variance in depression, anxiety, and pain interference, above and beyond joint pain severity.

Author Moriah Brier, author Dianne Chambless, author Laura Lee, and author Jun Mao declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Moriah J. Brier, University of Pennsylvania.

Dianne L. Chambless, University of Pennsylvania.

Laura Lee, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Jun J. Mao, Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta: 2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acsc-036845.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Puntoni M, et al. Switching to anastrozole versus continued tamoxifen treatment of early breast cancer: preliminary results of the Italian Tamoxifen Anastrozole Trial. J Clin Cncology. 2005;23:5138–5147. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thürlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, et al. A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2747–2757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark GM, Osborne CK, McGuire WL. Correlations between estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and patient characteristics in human breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:1102–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao JJ, Chung A, Benton A, et al. Online discussion of drug side effects and discontinuation among breast cancer survivors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:256–262. doi: 10.1002/pds.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman RE, Bolten WW, Lansdown M, et al. Aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: Clinical experience and treatment recommendations. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chim K, Xie SX, Stricker CT, et al. Joint pain severity predicts premature discontinuation of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:401–407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, et al. Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:936–942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan J, Winters LN, Habin K, Cashavelly B. Women’s experiences with antiestrogen therapy to treat breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:70–77. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickersham K, Happ MB, Bender CM. “Keeping the Boogie Man Away”: Medication Self-Management among Women Receiving Anastrozole Therapy. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:462121. doi: 10.1155/2012/462121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winters L, Habin K, Flanagan J, Cashavelly BJ. “I feel like I am 100 years old!” managing arthralgias from aromatase inhibitors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:379–382. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.379-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy BR, Myers LM. Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Prev Med (Baltim) 2004;39:625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy BR, Slade MD, Kasl SV. Longitudinal benefit of positive self-perceptions of aging on functional health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P409–P417. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sargent-Cox Ka, Anstey KJ, Luszcz Ma. The relationship between change in self-perceptions of aging and physical functioning in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2012;27:750–760. doi: 10.1037/a0027578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garland SN, Johnson B, Palmer C, et al. Physical activity and telomere length in early stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:413–421. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0413-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao JJ, Su HI, Feng R, et al. Association of functional polymorphisms in CYP19A1 with aromatase inhibitor associated arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R8. doi: 10.1186/bcr2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Bruner D, et al. Electroacupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: A randomized trial. Cancer. 2014;120:3744–3751. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalina J. Anxiety and chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012;26:180–181. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2012.676616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzberg AD, Robinson ME, Geisser ME, Gremillion HA. The effects of depression and chronic pain on psychosocial and physical functioning. Clin J Pain. 1996:118–125. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PS, Simon G, Kessler RC. The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:22–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spoormaker VI, van den Bout J. Depression and anxiety complaints; relations with sleep disturbances. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirth RJ, Edwards MC. Item factor analysis: Current approaches and future directions. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:58–79. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng X, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner DR, Neilson HK, Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical Activity After Breast Cancer: Effect on Survival and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2014;6:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown JC, Mao JJ, Stricker C, Hwang W-T, Tan K-S, Schmitz KH. Aromatase inhibitor associated musculoskeletal symptoms are associated with reduced physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2014;20:22–28. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:309–319. [Google Scholar]