Abstract

Past research has revealed that native listeners use top-down information to adjust the mapping from speech sounds to phonetic categories. Such phonetic adjustments help listeners adapt to foreign-accented speech. However, the mechanism by which talker-specific adaptation generalizes to other talkers is poorly understood. Here we asked what conditions induce crosstalker generalization in talker accent adaptation. Native-English listeners were exposed to Mandarin-accented words, produced by a single talker or multiple talkers. Following exposure, adaptation to the accent was tested by recognition of novel words in a task that assesses online lexical access. Crucially, test words were novel words and were produced by a novel Mandarin-accented talker. Results indicated that regardless of exposure condition (single or multiple talker exposure), generalization was greatest when the talkers were acoustically similar to one another, suggesting that listeners were not developing an accent-wide schema for Mandarin talkers, but rather attuning to the specific acoustic-phonetic properties of the talkers. Implications for general mechanisms of talker generalization in speech adaptation are discussed.

Keywords: perceptual learning, foreign-accented speech, generalization, spoken word recognition, talker specificity, adaptation

Speech perception requires listeners to extract a meaningful message out of a highly variable and sometimes ambiguous signal. Primary among many sources of variability are talker differences. Each speaker represents a unique combination of age, gender, vocal tract anatomy, idiosyncratic speaking style, and long-term language experience (e.g., regional dialect, native or non-native, bilingual or monolingual). Talker variability is manifested as a very wide variety of audible acoustic-phonetic variation in speech production, which further leads to differences in perceptual tasks (e.g., Peterson & Barney, 1952; Allen & Miller, 2004). Despite this variation, listeners efficiently identify spoken words across novel talkers, at least in most scenarios of native communication.

In order to understand how listeners accommodate talker variability, a large body of work has investigated how speech perception can be brought back to ‘normal’ (or at least, progress in this direction) in atypical communication scenarios. For instance, in initial encounters with acoustically-distorted speech or nonstandard speakers (e.g., foreign-accented), listeners typically experience greater perceptual difficulty (e.g., Dupoux & Green, 1997; Munro & Derwing, 1995; Clarke & Garrett, 2004). However, as listeners gain more experience with the particular type of speech variation, comprehension improves, sometimes within a few minutes (e.g., Dahan & Mead, 2010; Norris, McQueen, & Cutler, 2003; Maye, Aslin, & Tanenhaus, 2008). In cases where the phonetic deviation is associated with a particular talker (e.g., an unfamiliar accent), listeners are remarkably adept in learning the idiosyncratic acoustic details of specific talkers and thereby demonstrating experience-dependent adaptation (e.g., Bradlow & Bent, 2008; Dahan & Mead, 2010; Norris et al., 2003; Kraljic & Samuel, 2005, 2006, 2007). Critically, evidence suggests that as listeners adapt to non-standard speech, they modify existing phonetic representations used to evaluate standard speech and form a separate sound-to-category mapping for the adapted (nonstandard) talker (e.g., Dahan, Drucker, & Scarborough, 2008; Xie, Theodore, & Myers, 2017).

What remains unclear is how listeners draw on these recent individual-based learning experiences in perceiving novel talkers to whom they have no direct exposure. As we review below, despite much progress in documenting talker-specific perceptual improvements, results are ambiguous concerning the necessary conditions required for successful generalization across talkers (Bradlow & Bent, 2008; Sidaras et al., 2009; Kraljic & Samuel, 2007; Reinish & Holt, 2013). At the core of this question is whether listeners represent speech episodically, that is, packaging talker-specific acoustic detail together with linguistic information in memory, or whether listeners abstract away from talker-specific acoustic phonetic detail (Goldinger, 1998; Johnson, 2006; Pierrehumbert, 2006). This debate has led to recent hybrid accounts that allow for intermediate levels of talker knowledge (i.e., either by grouping talkers into higher-order categories, or by forming generative speaker models; Johnson, 2013; Kleinschmidt & Jaeger, 2015). As we shall elaborate in greater detail below, even these hybrid accounts have relatively little to say about how those “higher-order categories” are formed for talker representation or what factors aid the selection of “speaker models” during adaptation. Here, we present three experiments using a phonetic adaptation paradigm to explore the processes by which listeners generalize experience of particular foreign-accented talkers to novel talkers. We begin by briefly noting why foreign accent adaptation is a good place to look for evidence of cross-talker generalization. In relation to that, we describe evidence of talker-specific adaptation, either in the context of foreign-accented speech or native speech. Then we consider some empirical gaps and discuss the theoretical implications of closing these gaps, before laying out the specific goals of the paper and the general methods used to achieve these goals.

Perceiving foreign-accented speech is a particularly challenging task. Foreign-accented speech not only contains idiolectal differences seen in native-accented speech (for instance, a talker might have a personal tendency to raise pitch at the end of a phrase), but additionally presents global deviations from native language categories. These deviations are manifested as differences in the acoustic distributions of speech tokens along multiple dimensions for multiple categories (e.g., Flege, Munro, & Skelton, 1992), making recognition of non-native speech effortful and often times, inaccurate (e.g., Munro & Derwing, 1995). A classic example of this phenomenon is vowel assimilation for Spanish-accented speakers of English. Because Spanish does not have the vowel /I/ as in ‘pick’, native speakers of Spanish will often produce this word closer to the nearby vowel /i/, as in ‘peek’, which exists in both Spanish and English. Needless to say, speakers differ in their second language (L2) proficiency; speaker intelligibility can vary considerably across L2 speakers of the same accent (e.g., Flege & Schmidt, 1985; Bradlow, Akahane-Yamada, Pisoni, & Tohkura, 1999). At the same time, exactly due to systematic influences from their first language (L1), speakers with the same L1 do share some accent regularities in their L2 speech, for instance, they may contrast vowels by duration instead of spectral quality (e.g., Flege, Bohn, & Jang, 1997; Flege & Schmidt, 1985). In other words, talker variability in foreign accents is expressed in a hierarchical structure that can benefit perception if successfully learned, such that applying the acoustic-phonetic mappings from one accented talker to a new talker with the same non-native accent should yield faster comprehension benefits than simply learning the accent of the novel talker in a talker-specific (that is, accent-agnostic) way. Given this, there are potentially strong motivations to generalize across non-native speakers of the same accent, whereas generalizing across idiolectal differences in one’s native speech has less utility.

Talker-specific adaptation

A productive line of research has demonstrated that phonetic representations can be altered to reflect the properties of the current talker. As native listeners encounter unfamiliar pronunciations that cause perceptual ambiguity, they use top-down lexical information to constrain the interpretation of the ambiguous sound and alter the sound-to-category mapping accordingly (Norris et al., 2003). For example, if listeners hear a speaker pronouncing a sound ambiguous between /s/ and /f/ (denoted here as /?/), then hearing the sound in a carrier word such as ‘belie?’ (‘belief’) biases its interpretation as /f/. This exposure also affects subsequent interpretation of other similar ambiguous sounds in a way consistent with prior exposure. These findings, often referred to as ‘lexically-guided phonetic retuning’, reveal a specific mechanism by which the phonetic processing system might adjust to nonstandard talker-specific pronunciation variants by interfacing with the mental lexicon (e.g., Kraljic & Samuel, 2005; McQueen, Cutler, & Norris, 2006; Dahan et al., 2008).

How can phonetic representations be updated to reflect the properties of a foreign-accented talker? Using a similar paradigm to Norris et al. (2003), Xie et al. (2017) investigated how native-English listeners’ adapt to Mandarin-accented English. Word-final voiced stop consonants (e.g., the /d/ in ‘seed’) were selected as the focus of investigation because they are perceptually confusable with voiceless tokens (e.g., ‘seed’ may sound like ‘seat’) in Mandarin-accented English and they differ from native-English tokens. In English, vowels are generally lengthened before voiced consonants, and native-English listeners rely primarily on vowel length as an informative cue to voicing contrasts (e.g., Flege et al., 1992). In contrast, Mandarin-accented /d/ tokens sound /t/-like to native-English listeners because vowels are shorter before /d/ in Mandarin-accented English than those in native-accented speech, and vowel length tends not to be a useful cue to the identity of the following consonant (/d/ and /t/) in Mandarin-accented English. Consequently, native-English listeners, who tend to rely primarily on vowel length, often find Mandarin-accented /d/s perceptually ambiguous (Xie & Fowler, 2013). However, it is important to note that Mandarin-accented /d/ and /t/ tokens are in fact acoustically distinguishable if listeners attend to a different cue, namely the length of burst release (i.e., word-final /d/ tokens usually have noticeably shorter bursts than /t/ tokens). For this reason, Mandarin-accented /d/ and /t/ tokens in word-final position are easy to tell apart by Mandarin listeners, but not by English listeners.

Results of Xie et al. (2017) provided support for adaptation-elicited changes in lexical access. In this study, a cross-modal priming task at test probed changes in online processing of the accent. Following adaptation to a Mandarin-accented speaker, listeners showed more efficient processing of accented ‘seed’ (sounding like ‘seat’ to native-English listeners) and were more easily disambiguated from phonetically similar ‘seat’. Therefore, a brief exposure to a foreign-accented speaker (see also Eisner, Melinger, & Weber, 2013) created similar effects as those induced by exposure to an idiosyncratic speaker (McQueen, Cutler, & Norris, 2006) or long-term familiarity with a regional dialect (Sumner & Samuel, 2009). Taken together, this body of work suggests that listeners are capable of dynamically adjusting phonetic representations in adapting to specific talkers, non-native and native talkers alike. For an adapted talker, perceptual benefits manifest in both fewer offline confusions and more efficient online lexical disambiguation.

Generalization across talkers

Presumably, the newly formed phonetic representations, which differ from those used in perceiving typical native speech, could potentially render listeners an advantage when applied in appropriate contexts. In reality, whether listeners apply learning to new talkers is affected by a number of factors. First, it is sensitive to phonetic classes, as probed by phonetic categorization tasks (Norris et al., 2003; Kraljic & Samuel, 2005, 2006, 2007). Namely, listeners do not generalize across talkers for fricatives (e.g., /s/ vs. /f/) (e.g., Kraljic & Samuel, 2005, 2007; Eisner & McQueen, 2005), but do generalize across talkers for stop categories (e.g., /d/ and /t/) (Kraljic & Samuel, 2006, see also Kraljic & Samuel, 2007). Second, generalization seems to occur between some talker pairs but not others. Reinisch and Holt (2014) examined native-English listeners’ adaptation to artificially-created ambiguous sounds (midway between /s/ and /f/) embedded in Dutch-accented English. Listeners recalibrated the /s/-/f/ boundary for a female trained speaker and generalized the adjusted representation of the fricatives to a perceptually similar Dutch-accented female test speaker, but not to a perceptually dissimilar Dutch-accented male test speaker, even though all three speakers had distinct voices. In this study, “inter-talker similarity” seems to constrain generalization. Of note, in Witteman et al. (2013), native-Dutch listeners failed to generalize between two German-accented male speakers. So it is unclear whether it is indeed the overall ambiguity that matters, or rather, it is the more lower-level production properties, which lead to ambiguity, that matter.

Germane to the current study, the final impactful variable is talker variability during learning. Specifically, while experience with a foreign-accented speaker makes recognition of speech produced by that speaker more accurate (Gass & Varonis, 1984; Clarke & Garrett, 2004), such adaptation does not enhance speech intelligibility of a different speaker with the same accent (Jongman, Wade, & Sereno, 2003; Bradlow & Bent, 2008). On the other hand, exposure to a group of talkers who share a foreign accent appears to enhance intelligibility of other talkers with the same accent in some cases (Bradlow & Bent, 2008; Sidaras, Alexander, & Nygaard, 2009; but see Clarke, 2000; Wade et al., 2007 for negative evidence).

One limitation of prior investigations is that we do not know how recent experience with an accented talker influences online word recognition processes with a different talker. All studies on generalization have used offline categorization judgment or transcription measures, with the exception of Witteman et al. (2013), who did not find evidence of generalization in the stage immediately following accent exposure. More importantly, the reports by Bradlow and Bent (2008) and others (e.g., Sidaras et al., 2009) raised the possibility that listeners may build perceptual schemas that apply to a set of talkers, for instance, in the case of gaining perceptual expertise with talkers who share the same non-native accent. As suggested by Bradlow and Bent (2008; see also Sidaras et al., 2009), exposure to multiple talkers with the same accent could have enabled listeners to learn the acoustic-phonetic regularities in the accent, which helped them to tag certain types of acoustic variability as characteristic of a language community rather than characteristic of a specific talker (see also the discussion of Baese-Berk, Bradlow, & Wright, 2013). However, in these studies, adaptation has been exclusively measured by an increase of word recognition accuracy in offline transcription tasks, which cannot in and of itself unequivocally support the hypothesis. It is possible that the increased variability in the form of multiple talkers causes a general relaxation of the mapping from nonstandard speech tokens to word forms (since all speech tokens have to be real words in a transcription task), allowing many possible acoustic tokens to map to a word, without instigating any changes in specific segmental representations (e.g., Brouwer, Mitterer, & Huettig, 2012; McQueen & Huettig, 2012). Similarly, the null effects of single-talker exposure could indicate a lack of generalization of phonetic adjustments, or alternatively, it could be that the test measures of global intelligibility are not sensitive enough to detect talker-independent generalization for specific phoneme contrasts.

The idea that speech variability can be represented at the individual talker level and further at a group level is present in exemplar theories (e.g., Johnson, 2006, 2013) and more recently, a Bayesian approach to speech perception (Kleinschmidt & Jaeger, 2015). A challenge for these theories is a specification of how a group-level perceptual schema, which allows listeners to achieve robust perception in a way less bounded by talker-specific properties, is developed, and how it is used to facilitate online processing. In exemplar models, a group-like percept emerges from activations of individual exemplars that bear some similarity to the current input. As individual exemplars are activated, the associated linguistic category (i.e., a word ‘seed’) and socio-phonetic category (i.e., female) are also activated and in turn strengthen the activations of individual exemplars (Johnson, 2006). It is, however, not clear how less observable categories such as accent types are formed by combing a set of unlabeled exemplars. For instance, for listeners who do not have much experience of foreign-accented speech, one talker’s accent type cannot be easily judged without other external information, and yet listeners must learn to represent the talker-related variation properly. Kleinschmidt and Jaeger (2015) suggest that such higher-order categories (i.e., group membership of talkers) are inferred based on listeners’ past experience and the current input. At any time, listeners not only have to infer from the current input what is being said, but also who is speaking, in order to be able to select the appropriate generative speaker model; based on the selected speaker model (i.e., the prior in Bayes’ terms), listeners then infer the speech category with the largest posterior probability that could have generated the current input. In other words, priors can only facilitate perception if listeners select the right prior (e.g., selecting the Mandarin-accented prior) and this process is itself inferential. Theoretically, listeners can combine top-down (e.g., a Mandarin-accented speaker is talking) and bottom-up acoustic information to make this inference. Yet empirically there is little evidence of whether and how listeners do this. Notably, in this Bayesian approach, this inference of speaker model is inherent in speech perception regardless of whether listeners have really formed a group-level schema or not.

The present study

Here, we hope to provide more information about how listeners generalize their prior experience to novel speakers by asking two questions. First, does phonetic adaptation account for generalization from a single talker as well as generalization from a group of talkers? Our first goal is to validate the hypothesis that multiple-talker exposure benefits talker generalization via a retuning of specific phonetic categories. We adapted the phonetic retuning paradigm to allow a direct comparison of adaptation and generalization effects following single-talker exposure to that following multiple-talker exposure. Generalization is measured by the extent to which experience with previously exposed talker(s) facilitates recognition of the same sound category produced by novel talkers across word contexts in an online lexical task (the same cross-modal priming task in Xie et al., 2017; detailed predictions are given in the General Methods).

A second question is: what sources of information are used to constrain talker generalization? Our goal is to tease apart the contribution of explicit knowledge of talker information (e.g., “these talkers have a Mandarin accent”) versus that of bottom-up acoustic similarity in constraining generalization. Kraljic and Samuel (2007) explained that talker generalization is contingent on the extent to which the phonetically-relevant acoustic cues also serve as indicants of talker identity. For instance, spectral cues that distinguish fricatives (for instance, /s/ from /ʃ/) tend to vary more substantially across talkers and are more predictable given talker information than the temporal cues that distinguish a /d/ from a /t/ (Newman, Clouse, & Burnham, 2001; Allen, Miller, & DeSteno, 2003); thus, listeners tend to adapt in a talker-specific manner for fricatives (but see Reinisch & Holt, 2014) but not for stops. However, it is unclear whether the discrepancy between phoneme classes reflects “bottom-up constraints” that are specific to the speech signal (i.e., particular acoustic properties). Or rather, it reflects top-down expectations about speakers or accents that guide listeners to encode the speech signal in a more talker-specific manner when talker-identity characteristics tend to be present in the altered segment itself (e.g., fricatives, vowels).

General Methods

Experiment 1 (multiple talker condition) investigated whether exposure to a group of talkers that share the same accent elicits phonetic adaptation to the phoneme of interest (word-final /d/) and further generalizes to a different talker with the same accent. Experiments 2 and 3 (single talker condition) continued to examine factors that constrain generalization by comparing generalization effects across different talker pairs. Each experiment consisted of an exposure phase and a test phase. During the exposure phase, two groups (experimental vs. control) of native-English listeners heard words produced by five Mandarin-accented speakers (Experiment 1) or by a single speaker out of the five speakers (Experiments 2 and 3) and completed an auditory lexical decision task. The experimental group heard Mandarin-accented /d/-final words in English (e.g., overload) that were produced closer to /t/ than would be expected of native-English speakers, while the control group heard replacement words that did not contain any example of /d/ (e.g., animal). Following exposure, listeners’ adaptation to the accent was tested in a cross-modal priming task to assess spoken word recognition. Crucially, speech materials for the test phase were produced by a novel Mandarin speaker (kept constant across experiments). We asked if listeners’ prior experience with the exposure talkers’ pronunciations of /d/-final words (e.g., overload) affects subsequent online recognition of novel /d/-final words (e.g., seed) and their voicing minimal pairs (e.g., seat) when produced by the test talker, by comparing the priming effects in the experimental group to that in the control group. Improved spoken word recognition for the test talker in the experimental group would suggest that listeners generalized the adjusted phonetic representation of the /d/ category across talkers. In each experiment, we combined acoustic analysis with listeners’ behavioral performance as well as with their subjective reports of talker and accent similarity.

Speakers

Six male native-Mandarin speakers, who were L2 learners of English and acquired English in mainland China, were selected from a larger speaker pool. All speakers were undergraduates or graduate students from University of Connecticut. A pilot study suggested that speakers varied in their intelligibility, with Speaker 1 in the medium range. In a previous study, we reported evidence of talker-specific adaptation for Speaker 1 (Xie et al., 2017). Here Speaker 1 served as the test talker across all experiments. Speakers 2–6 were exposure talkers in Experiment 1; Speaker 2 and 4 served as the exposure talker in Experiment 2 and 3, respectively. Crucially, Speaker 2 and 4 were both matched with Speaker 1 in intelligibility and the degree of ambiguity in their /d/ productions, but they had different acoustic patterns in the production of word-final /d/ tokens. In addition, the overall ambiguity of critical exposure words produced by the five speakers as a group in the multiple-talker condition (Experiment 1) were also equated to those produced by Speaker 2 and Speaker 4 alone. Detailed information for the pilot study and demographic information of all speakers (see Table A1) are presented in Appendix A. In all experiments, participants were not informed about the number of speakers, the change of speakers between exposure and test, or that the speakers were non-native speakers of English. After completing the exposure and test phase, they were asked to make subjective judgments about the speakers (see details in Methods, Experiment 1).

Participants

Participants were undergraduates at University of Connecticut. They gave informed consent according to the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board and received course credits for their participation. All were monolingual English speakers with no hearing or visual problems. According to self-reports at the end of the experiment, all participants had no or minimal prior experience with Mandarin-accented English or the Mandarin language. Each experiment tested a separate group of participants; participants were randomly assigned into the experimental group or the control group in each experiment.

Speech Materials

Stimuli for the exposure phase consisted of 30 critical words, 60 filler words and 90 nonwords in English; all exposure words were multisyllabic. Critical words were 30 /d/-final words (e.g., overload) for the experimental group and these were replaced by 30 extra filler words for the control group. None of the critical /d/-final words had minimal pair words ending in /t/. Stimuli for the test phase were identical for both exposure groups, consisting of 240 monosyllabic words. Critical test words were 60 /d/-final words taken from /d/-/t/ minimal pairs such as “seed-seat”; the rest were filler words. All /d/ tokens appeared only in the critical exposure (experimental group only) and test (both groups) words; participants heard no other alveolar stops or other voiced stops in the experiment; voiceless stops (/p/ or /k/) occurred only in word-initial position. Recordings were made in a sound-proof room using a microphone linked to a digital recorder, digitally sampled at 44.1 kHz and normalized for root mean square (RMS) amplitude to 70 dB SPL. It is important to note that participants did not have exposure to /t/ words throughout the experiment. Thus, any difference between the experimental group and the control group in the test task would be solely driven by the exposure to /d/ words, instead of from learning the contrastive cues used by /d/ and /t/ word pairs.

Procedure

Exposure phase

Each participant completed an auditory lexical decision task during exposure, which was immediately followed by a cross-modal priming task. During the exposure phase, listeners heard words produced by the exposure talker(s) from the experimental list or the control list. Items were presented in a random order. Participants were instructed to decide whether each auditory stimulus was a real English word and to press a yes/no button as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy.

Test phase

At test, participants heard words produced by the test talker. Participants were told that they would hear auditory words (primes) but immediately after that they would see visual letter strings (targets) presented on the screen. The task was to decide with a yes/no button press whether the visual stimuli were real English words or not. On critical trials, 60 minimal pairs of /d/- and /t/-final words appeared as visual targets, in four different prime –target pairing types: /d/-final words as visual targets preceded by an identical prime (e.g., seed –SEED) or an unrelated prime (e.g., fair –SEED); /t/-final visual targets preceded by a minimal pair contrast (e.g., seed –SEAT) or an unrelated prime (e.g., fair –SEAT). Words in each set of minimal pair items were rotated over four lists, counterbalanced across participants; within each list, they were assigned in equal proportions in the four prime-target types. Non-critical trials were identical across counterbalanced lists; in each list, half the targets were nonwords. The test lists were pseudo-randomly ordered such that no more than four words or nonwords appeared in a row, and the critical trials were approximately evenly spaced. There were two reversed orders for each list.

Stimuli were presented using Eprime 2.0.8 running on a desktop computer. Audio stimuli were delivered via Sennheiser HD280 headphones at a comfortable listening level constant across participants; visual targets were shown in white Helvetica font in lower case on a black background in the center of the computer screen. During exposure, ten practice trials were given to the participants before the actual task to familiarize them with the task procedure. The practice items were not used in the actual exposure task. Each trial was preceded by a 1000 ms fixation cross at the center of the screen and was presented with an inter-onset interval of 3000 ms. During test, ten practice trials of the cross-modal priming task were given to participants, followed by the actual test. The inter-trial interval was 1400 ms, timed from a button press response to the onset of the next auditory prime. Visual targets were presented immediately at the offset of the auditory prime and stayed on the screen for 2 s unless terminated by a response. Reaction times (RT) were measured from visual target onset. During both phases, participants were told to respond as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. Responses were made via keyboard with two buttons labeled ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Assignment of the ‘yes’ button to the right or left hand was counterbalanced across participants.

At the end of the behavioral tasks, listeners made qualitative judgments about the speakers’ voices and their accents. They were also asked to rate the voice similarity and accent similarity of the speakers on a scale from 1 to 7, with 7 being identical and 1 being very different. Participants were specifically instructed to rate the accent similarity in terms of the type of accent (language community), rather than the strength of accentedness.

Predicted Patterns for Generalization

If learning is generalized to the test talker, we expect a similar pattern of priming to that following talker-specific adaptation (Xie et al., 2017). Specifically, for control participants, who have no prior exposure to Mandarin-accented /d/ pronunciations in word-final position, we expect that the auditory form of /d/ will be perceptually ambiguous and lead to equal priming magnitudes for both /d/-final words and /t/-final words (e.g., seed-SEED = seed-SEAT). For experimental participants, we expect that generalization of learning leads to increased match between the auditory input and the intended lexical representation such that /d/-final words will be primed to a greater extent than /t/-final words (e.g., seed-SEED > seed-SEAT). Thus, we take reduced lexical competition, namely larger priming for intended targets (/d/-final words) than for competitors (/t/-words), as a sign of adaptation and generalization. Of note, we still expect significant priming for both types of words, given our previous observation that adaptation to a foreign accent may not be as complete as adaptation to a native variant. In past research, adaptation to ambiguous tokens embedded in native speech usually leads to strong priming for intended lexical forms only, without significant priming for lexical competitors (e.g., McQueen et al., 2006). That is, once adapted, ambiguous items function like clear, unambiguous speech and the amount of lexical competition is minimal. We do not expect this to be the case for foreign accent adaptation. However, if exposure to different talkers, especially in the form of multiple exposure talkers, gives listeners additional benefit in the phonetic adjustment, we may observe strong priming for the target word (e.g., seed-SEED) and not for the competitor (e.g., seed-SEAT).

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 tested the hypothesis that exposure to multiple talkers of the same accent elicits phonetic retuning of specific categories and such adaptation accounts for improved word recognition, just as in talker-specific adaptation. Evidence from intelligibility/word transcription tasks suggests that listeners generalize from multiple talkers to one or more novel talkers (Bradlow & Bent, 2008; Sidaras et al., 2009). It is suggested that listeners can extract systematic information across multiple talkers to overcome talker-specific variation and make general adjustments transferrable to new members with the same accent. We refer this as the ‘extraction’ hypothesis and specify the extraction hypothesis in two scenarios. If cross-talker generalization reflects active abstraction across talkers guided by top-down expectations, then listeners must be aware, at some level, of the shared accent among talkers in the multiple-talker exposure conditions. It is possible that as listeners are exposed to an unfamiliar foreign accent, they not only make online adjustments for specific segments, they also build up a representation of what the accent sounds like (see results from Skoruppa & Peperkamp, 2011 and Trude & Brown-Schmidt, 2012 for comparison). The latter type of learning would provide listeners a basis to infer whether talkers are similar and help to constrain generalization when new talkers are encountered. In this case, we would see generalization to new talkers when the talker is judged by listeners to have a similar accent to the exposure talker(s).

A second possibility is that talker generalization is driven by bottom-up similarity (of the segment) among talkers, specifically by retuning listeners’ attention to particular aspects of the segmental productions (for instance, certain regions in the perceptual space or specific acoustic dimensions) that are stable across talkers. In this case, listeners’ explicit awareness of a similar accent is not necessary. However, it is crucial that talkers show commonalities along acoustic dimensions that are distinctive for specific phonemes. If this is the case, we would see generalization when acoustic properties (of the specific segment) of the novel talker resemble those of the exposure talker(s).

Alternatively, what appears as ‘generalization’ of adaptation might simply reflect a ‘general relaxation’ in the mapping from nonstandard speech signals in a foreign accent to lexical entries, without the mediation of an altered phonetic representation (see discussion of Baese-Berk et al., 2013). Similar explanations have been proposed to explain listeners’ greater tolerance for acoustic mismatches in the presence of unreliable acoustic input (e.g., noise-embedded speech; Brouwer & Bradlow, 2016). That is, listeners might not have learned any particular phonetic features of the non-native accent, but rather, they become more tolerant of acoustic mismatches after hearing multiple speakers producing non-canonical speech and thus accept phonologically similar words as speech targets. If so, listeners should show increased activation for target words (/d/-final words) as well as their phonological competitors (/t/-final words) upon hearing the critical /d/-final words—that is, accented /d/ words might indiscriminately activate both /d/-final and /t/-final words. The performance of control participants serves as a baseline.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-two monolingual English speakers participated in this experiment. Four participants were excluded for poor performance in the exposure phase (response accuracy below or at chance level) or misunderstanding the test task. Forty-eight participants were included in the following analyses, with equal numbers of participants in each exposure group (experimental vs. control).

Speech materials and procedure

The materials and procedure were described in the General Methods. Participants were exposed to Speakers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 and were tested with Speaker 1 (Multi 1 → Speaker 1). Equal number of words in each exposure list was spoken by each of the five exposure talkers, keeping the total number of exposure words constant across experiments. This means that participants in the experimental list heard /d/-final words from all five speakers (each speaking a fifth of the /d/-final words). Following the exposure and test phase, participants were immediately asked to a) report the number of speakers in each phase; b) categorically indicate whether the accents of speakers (between exposure and test phase) were the same or not; c) rate the accent similarity between exposure talkers and test talkers on a scale of 1–7; d) guess accent type of the talkers if possible.

Results

Exposure

Data were collapsed across exposure talkers, and response accuracies are presented in Table B1. Critical /d/-final words were largely judged to be real words by the exposure group (M = .79, SD = .09). The fact that these words were recognized with sufficiently high accuracy is important, because non-native phonetic and/or prosodic patterns in the Mandarin accent might have biased listeners to misinterpret some of the /d/-final words as /t/. Had it been the case, we would not observe strong effects of lexically-guided phonetic retuning for the exposure talker, let alone generalization to novel talkers. Accuracies for each type of words were comparable between the experimental group and the control group.

Test

In this experiment and in all subsequent experiments, three words (plod, moot, spate) out of 120 items were discarded due to low accuracy in response to these words. Table B2 shows mean error rates and RTs in the test phase. Priming effects are shown in Fig. 1. Responses (4.8% of correct trials) above or below 2 SDs from the mean of each prime type in each exposure group were excluded from the RT analysis. A mixed-effects model was fitted with RTs as the dependent measure. The model included exposure group (experimental vs. control), target type (/d/-final vs. /t/-final words), prime type (related vs. unrelated) and their interactions as fixed effects. Random effects included by-subject intercepts and by-item intercepts and slopes for priming type, which had the maximal random effect structure justified by the data (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008). We used the lme4 package in R (Bates, Maechler, Bolker & Walker, 2014) to conduct the analysis. All the independent variables were contrast coded as follows: exposure group: experimental = 1, control = −1; target type: /d/-final targets = 1, /t/-final targets = −1; prime type: related = 1, unrelated = −1. There was a significant priming effect: responses were faster to related than to unrelated primes (β = −15.91, SE = 2.78, p < .0001). The /d/-final targets elicited slower responses than /t/-final targets (β = 14.54, SE = 5.12, p < .01). There was a significant main effect of exposure group (β = −20.70, SE = 9.58, p < .05), driven by overall faster responses in the experimental group than the control group1. Of interest, there was a significant three-way exposure group × target type × prime type interaction (β = −6.16, SE = 2.09, p < .01). No other effects were significant at the .05 level. In addition, we tested for a Trial effect by including Trial Number as a predictor, to see if the generalization occurred immediately in the test phase. There was no main Trial effect or any interaction with the primary predictors (ps > .10). Thus, the three-way interaction, which indicated different response patterns between the two exposure groups, was not a result of task learning within the test phase.

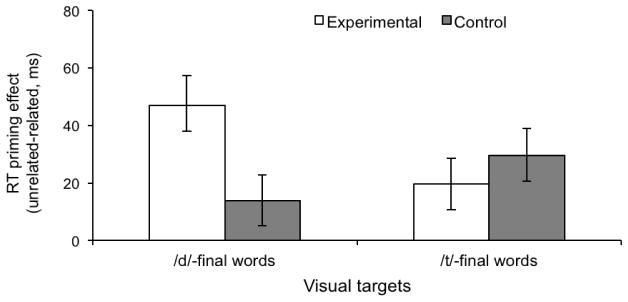

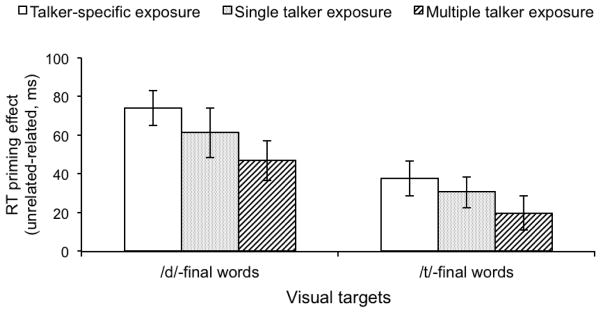

Figure 1.

Experiment 1 (Multi 1 → Speaker 1) test results: Priming of /d/-final words (RT in fair-SEED trials minus RT in seed-SEED trials) and /t/-final words (RT in fair-SEAT trials minus RT in seed-SEAT trials) for participants exposed to critical words (Experimental group) or replacement words (Control group). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

We then asked whether within each exposure group, the priming magnitudes differed between target types. Starting with the control group, there was a main priming effect (β = −12.29, SE = 3.77, p < .01) but no interaction between target type and prime type (β = 5.59, SE = 3.77, p = .14), suggesting that auditory /d/-final words primed -/d/ and -/t/ targets equally. This was expected for Mandarin-accented /d/ productions which are perceptually ambiguous for native-English listeners. In contrast, for the experimental group, a main priming effect (β = −19.08, SE = 3.13, p < .001) was modulated by a prime type-by-target type interaction (β = −7.92, SE = 3.14, p < .05), driven by larger priming for “seed – SEED” trials (β = −28.07, SE = 4.88, p < .0001) than for “seed – SEAT” trials (β = −10.76, SE = 4.07, p < .05). This pattern paralleled previous findings of talker-specific learning when listeners were trained on the same talker (Xie et al., 2017; Eisner et al., 2013). In other words, multiple talker exposure elicited generalized adaptation to a novel talker. In addition, the priming for -/d/ targets was larger in the experimental group than in the control group (β = −9.11, SE = 3.18, p < .01), whereas the priming for -/t/ targets was comparable across groups (β = 3.06, SE = 2.75, p = .27).

Analyses of listeners’ judgments of accent similarity showed that although listeners heard multiple talkers during exposure, they were largely unfamiliar with the type of accent and expressed low confidence in their judgments. Seven participants in the experimental group and two participants in the control group reported “same accent”, while the majority of participants reported “similar but different accents” or “different accents”. The mean of Likert ratings of accent similarity on a scale of 1–7 was 5.02 (Experimental group, SD = 1.60) and 4.64 (Control group, SD = 1.09), respectively. Due to the low confidence in accent judgments and the unequal number of participants reporting each type of answer, we did not further analyze this data.

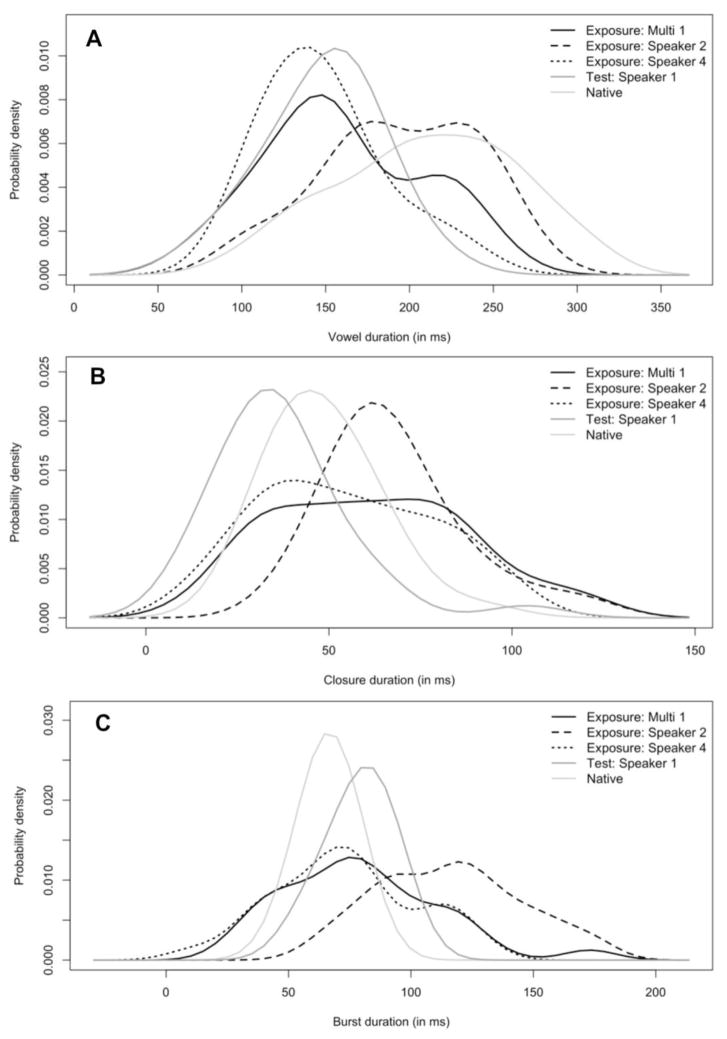

To investigate if an ‘acoustic similarity’ account was consistent with the generalization pattern, we measured three acoustic properties that are diagnostic of voicing in English stops: preceding vowel duration, closure duration and the length of burst and aspiration of the stop. In general, vowel durations are longer before voiced than voiceless stops; closures and bursts are shorter (e.g., Hillenbrand et al., 1984). Word length substantially changes the duration of temporal acoustic cues (Lehiste, 1972). For this reason, instead of comparing the exposure words (3–4 syllables) produced by the multiple exposure talkers to the test words (monosyllabic) produced by the test talker, which was the order heard by the participants, we compared the critical d/-final words from the exposure phase produced by the multiple exposure speakers to the same set of exposure words produced by Speaker 1 (not presented in the current experiment). This comparison helps to gauge the similarity between talkers in terms of word-final /d/ productions. We did not take any additional measures to control for speech rate, as we did not have a priori predictions whether listeners might use it as a cue for talker similarity (see Reinisch, 2016 for positive evidence). Acoustic distributions are presented in Fig. 2. For comparison, we also present the aggregated production data from four male native-English speakers in light grey lines. Mandarin-accented /d/ tokens tend to have shorter preceding vowels and longer bursts than native-accented English (see Fig. 2), making them /t/-like when perceived by native-English listeners. Independent samples t-tests indicated that Speaker 1 produced critical words with significantly shorter closure durations than exposure speakers (as a group) did (t(58) = 4.169, p < .001), but they had similar mean durations for vowel (t(58) = 1.145, p = .26) and burst (t(58) = .11, p = .91).

Figure 2.

Probability density plots of acoustic measures of exposure /d/-final words (vowel duration, closure duration, and burst duration) for the exposure talkers in Experiments 1 (black solid lines), 2 (black dashed lines) and 3 (black dotted lines), as well as the test talker (dark grey lines). For comparison, light grey lines show native-English token distributions. The area under each curve equals 1.

Discussion

Experiment 1 indicated that following multiple-talker exposure, listeners did not merely include more competitors as a viable match to existing word forms. Instead, listeners retuned the sound-to-category mapping for word-final /d/, and the phonetic retuning led to improved word recognition for a novel talker by decreasing the amount of lexical competition among phonetically-similar words. Our results extended the findings of Bradlow and Bent (2008) by providing the first direct evidence that brief exposure to multiple talkers indeed elicited retuning of specific phonetic categories that was generalizable within the accent to a novel talker.

The results did not support a ‘top-down expectation’ account to explain talker-independent adaptation, given that listeners were largely naïve of the speakers’ accents. In fact, many listeners in the experimental group did not perceive the speakers to have the same accent or sound similar to one another, despite an overall adaptation effect. Thus, it is unlikely that listeners generalized to the novel talker based on explicit knowledge of shared group membership or intentional talker clustering.

On the other hand, the results were consistent with a ‘bottom-up similarity’ account in that the multiple talkers as a group had similar production patterns as the test talker. Results from a pilot intelligibility study revealed that all speakers bore noticeable traces of foreign accents and all speakers produced /t/-like /d/-final tokens, although to various extents. In this regard, the speakers did possess talker-independent regularities at the phonological level. Relatedly, Reinisch and Holt (2014) showed that listeners generalized their experience of a speaker’s ambiguous fricative productions (/f/ or /s/) to another speaker only when the productions of the two speakers had a similar degree of ambiguity. Their results did not reveal at which sub-lexical level listeners were generalizing: phoneme category (e.g., ‘ambiguous sounds are /f/s’) or specific acoustic cues (e.g., ‘spectral centroid within this range denotes /f/’), as these two sources of information were confounded (see also Kraljic & Samuel, 2006).

In Xie et al. (2017), native-English listeners adapted to Speaker 1 and showed a re-weighting of acoustic cues, favoring burst length over vowel length as an informative cue to Mandarin-accented voicing tokens. Listeners could have engaged in the same kind of perceptual adjustments for the exposure talkers in the current experiment and tracked the acoustic-phonetic detail of each talker. We thus examined whether Speaker 1 aligned with any of the five exposure speakers in particular. Pairwise comparisons were conducted to compare exposure words produced by Speaker 1 to those produced by each exposure speaker. Comparing the mean values of the acoustic distributions, a few differences reached statistical significance at the .05 level: Speaker 1 had longer bursts than Speaker 3 (p < .01) and shorter bursts than Speaker 5 (p < .05); he also had shorter closures than Speaker 6 (p < .05). Importantly, Speaker 1 differed from Speaker 2 in every acoustic dimension, both in terms of the mean values (ps < .001) and the degree of within-talker variability. In contrast, the category means were well-aligned between Speaker 1 and Speaker 4 (see Fig. 2), with no difference on any of the three acoustic measures (ps > .50), although Speaker 4 demonstrated larger within-talker variability. Of note, Speaker 2 and Speaker 4 were both matched with Speaker 1 in intelligibility: their productions of /d/-final words were of equivalent ambiguity (in terms of /t/-likeness; see Appendix A).

Thus, the multiple talkers differed from one another in terms of the acoustic distributions of their /d/ productions, despite the overall /t/-like /d/ productions. In other words, there was little space for listeners to extract systematic acoustic-phonetic properties across all talkers that were generalizable to the test talker. This raises the question whether listeners could have relied on one or more out of the five (instead of all five) exposure talkers for adaptation and generalization; and if so, what did they rely on: overall talker intelligibility in /d/ productions, or specific acoustic characteristics? Given that Speaker 2 and Speaker 4 presented dissociable characteristics in these two aspects, they were used as the exposure talker in Experiments 2 and 3, respectively. In the next two experiments, we explored three possibilities that might account for the talker generalization in this experiment. One possibility is that listeners generalize retuned phonetic representations to speakers of similar intelligibility (i.e., producing /t/-like /d/s to the same extent). In this case, we should observe positive generalization to Speaker 1 from both Speaker 2 and Speaker 4. Alternatively, if listeners pay close attention to acoustic-phonetic distributions in each speaker’s production and adjust the phonetic category boundaries and internal structures accordingly, then we should observe larger generalization from Speaker 4 to Speaker 1, but smaller or no generalization from Speaker 2 to Speaker 1. Another possibility is that multiple talker presence is necessary for robust generalization to novel foreign-accented speakers. If this is the case, we would not observe generalization to Speaker 1 from either Speaker 2 or Speaker 4. Given that talker-to-talker generalization for stop consonants has been observed for native-accented speakers, such a result would suggest that listeners are highly conservative and are reluctant to generalize for this unfamiliar accent, absent evidence of the generality of the speech variant (which is likely available in the form of multiple talkers).

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we examined the transfer of adaptation to foreign accents from one Mandarin-accented talker (Speaker 2) to another (Speaker 1). If talker generalization relies on production similarity at the phonological level (e.g., /d/ tokens sound like /t/), then perceptual learning results should be transferrable from Speaker 2 to Speaker 1, yielding better word recognition among experimental participants than control participants. As such, the priming patterns in the cross-modal priming test task will be similar to that in Experiment 1. If talker-generality of phonetic retuning for stops previously observed in native speech (Kraljic & Samuel, 2006) is the consequence of talker similarity at the acoustic-phonetic level, then we would not find evidence for talker generalization in this experiment, as the exposure talker and test talker were not acoustically similar in their productions of the critical segment. In addition, to assess whether listeners have a good estimate of whether their prior experience applies, we also analyzed their explicit reports about talker and accent similarity.

Methods

Participants, materials and procedure

Fifty students from University of Connecticut participated in this experiment. Four participants were excluded for poor performance during the exposure phase or for misunderstanding the test task. Forty-six participants were included in the analyses, with equal numbers of participants in the experimental and the control group (n = 23 each). The materials and procedure were identical to those in Experiment 1, except that now all exposure items were spoken by Speaker 2, and all test items by Speaker 1 (Speaker 2 → Speaker 1). After participating in the behavioral tasks, listeners were asked to judge whether the exposure talker and the test talker were the same person. If their answer was “No”, they were further asked to rate the voice similarity and accent similarity (in terms of the type of accent, not the strength of it) of the speakers on a scale from 1 to 7, with 7 being identical and 1 being very different.

Results

Exposure

Response accuracies are presented in Table B1. Of interest here, critical /d/ words were largely judged to be real words by the experimental group (M = .84, SD = .07). This accuracy rate was comparable to that in our previous study (Xie et al., 2017). Thus, we judge that speech tokens produced by Speaker 2 should provide sufficient lexical information to elicit an adjustment in the phonetic representation of /d/.

Test

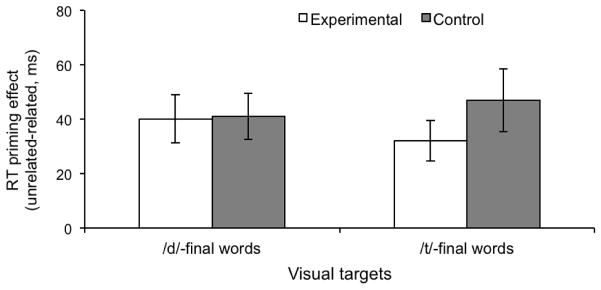

Responses (3.2% of correct trials) above or below 2 SDs from the mean of each prime type in each exposure group were excluded. Table B2 shows mean error rates and reaction times (RT) in the test phase. Fig. 3 showed the magnitude of RT priming effect as a function of exposure group and visual target type. As in Experiment 1, responses were faster to related than to unrelated primes (β = −19.74, SE = 2.93, p < .0001). /d/-final targets elicited slower responses than /t/-final targets (β = 16.40, SE = 5.30, p < .01). There was no interaction between target type and prime type (β = −0.98, SE = 2.93, p = .74). Of note, although the priming size was numerically larger for /d/-final words than for /t/-final words among the experimental group and was in the opposite pattern among control participants, the three-way exposure group × target type × prime type interaction was not significant (β = −2.32, SE = 2.31, p = .32). The lack of a three-way interaction stood in contrast to results in Experiment 1 and indicated no influence of exposure group on the priming magnitude for either /d/-final or /t/-final targets. Thus, exposure to Speaker 2’s production of critical /d/ words did not improve recognition of /d/-final words produced by Speaker 1. Of note, it was possible that the generalization effect, if any, were to emerge gradually such that it became stronger over time despite of a lack of an overall effect. To this end, we included Trial as an additional predictor into the model: there was a non-significant Trial effect (β = −.08, SE = .05, p = .10), but no interaction between Trial and any of the other predictors (ps > .10). The inclusion of this additional predictor did not qualitatively change any of the interactions among the three primary predictors either.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2 (Speaker 2 → Speaker 1) test results: Priming of /d/-final words (RT in fair-SEED trials minus RT in seed-SEED trials) and /t/-final words (RT in fair-SEAT trials minus RT in seed-SEAT trials) for participants exposed to critical words (Experimental group) or replacement words (Control group). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

We then statistically assessed whether participants’ response patterns differed as a function of their reports of talker and/or accent similarity. Descriptive statistics of voice and accent similarity rating were reported in Table B3. Fourteen out of twenty-three participants in the experimental group and eleven out of twenty-three participants in the control group identified the exposure talker and test talker as the same person. Voice judgment (same speaker vs. different speakers) as a binomial factor (contrast coded as follows: same speaker = 1, different speakers = −1) was included into the mixed-effects model. The model included exposure group, target type, prime type, voice judgment and their interactions as fixed effects. Results revealed no main effect of voice judgment (β = 1.46, SE = 9.63, p = .88). Of interest, voice judgment did not interact significantly with other factors either (ps > .10). Thus, even when listeners believed that the test and exposure talkers were the same person, no generalization was observed.

A similar analysis was conducted on the priming patterns with respect to individual participants’ accent judgments. Nine out of twenty-three participants in the experimental group and fifteen out of twenty-three participants in the control group identified the exposure talker and test talker as having the same accent. Accent judgment was contrast coded as a binomial factor (same accent = 1, different accents = −1). Again, there was no significant interaction between accent judgment and other factors (ps > .05), suggesting that the perception of accent similarity between the speakers did not affect the generalization pattern.

Discussion

In the current experiment, no clear group difference was observed during the test phase. For both groups, /d/-final words (‘seed’) equally activated both /d/ and /t/ words (‘seed’ and ‘seat’), without favoring either one. Despite prior exposure to a talker who produced /t/-like /d/ words, the experimental group did not recognize critical test /d/-final words better than the control group. Moreover, the null results in this experiment contrast with positive generalization following multiple talker exposure in Experiment 1. Critically, Speaker 2 was matched in intelligibility of /d/ productions with Speaker 1, and with the multiple speakers as a group (Experiment 1). The lack of generalization suggested that a mere match in the overall degree of intelligibility between talkers was not sufficient to promote talker generalization.

The results speak to the inconsistent findings on talker-to-talker generalization as reviewed in the introduction: fricatives were found to elicit talker-specific adaptation, whereas stop consonants led to talker-independent adjustments (Kraljic & Samuel, 2006, 2007; Eisner & McQueen, 2005). Given the absence of generalization for stop consonants in the current experiment, it is unlikely that the previous discrepancy between phoneme classes reflected processing differences for spectral vs. temporal cues. Namely, listeners did not indiscriminately encode temporal cues in a talker-independent manner for stops across all talkers. Together with the findings of Reinisch and Holt (2014), our results provided evidence that completed a double dissociation between phoneme class and acoustic similarity: they reported one case of talker-to-talker transfer for perceptual learning of fricatives; for stop consonants, we did not observe generalization between two Mandarin-accented speakers when the acoustic patterns were misaligned between them. Moreover, in Reinisch and Holt (2014), generalization was observed despite the fact that listeners judged the two speakers to have different accents, and there was clearly no confusion between voices. Similarly, results of Experiment 2 indicated that the lack of generalization was not affected by listeners’ explicit perception of talker voices or accents. Together, there does not seem to be a general tendency to process stop consonants vs. fricatives in inherently different ways as they are associated with talker identity. Rather, a ‘bottom-up similarity’ account is consistent with the generalization patterns for both stops and fricatives.

The current results also aligned with findings from other paradigms on foreign-accented speech, which consistently reported that training on words spoken by one foreign-accented speaker did not improve intelligibility of other speakers (e.g., Bradlow & Bent, 2008; Jongman et al., 2003). Our analysis suggests that as foreign-accented speakers transfer their native phonology to a second language, the realization of specific phonemes could be inconsistent across speakers; this inconsistency might have constrained listeners from generalizing across talkers in previous studies. Put simply, while speakers of Mandarin may share the same general accent in English, the ways in which this accent is manifested can vary significantly across segments. Similarly, we can imagine that in other situations where listeners may have more accent knowledge (for instance, given sentence-level stimuli, Bradlow & Bent, 2008), belief that the talkers share the same accent is not sufficient to override a bottom-up mismatch.

The lack of generalization from Speaker 2 to Speaker 1 in the current experiment implies that listeners did not merely perceive the Mandarin-accented speakers as people who “produced /d/-like /t/s”. In Experiment 3, we continued to test the hypothesis that listeners are sensitive to the fine-grained phonetic detail in foreign-accented speech and talker similarity at this level leads to successful generalization between accented talkers.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was conceptually and procedurally similar to Experiment 2, except that listeners were exposed to a different speaker during exposure. Speaker 4 was selected out of the Multi 1 group because his productions of /d/ words were acoustically similar to the test talker (Speaker 1) along all examined acoustic dimensions. Comparison of Experiments 2 and 3 will elucidate whether the degree of acoustic similarity between speakers modulates the generalization of learning from a specific talker in accent adaptation, or whether multiple-talker exposure is necessary in order to show generalization to a new talker.

Methods

Participants, materials and procedure

Forty-eight participants participated in the experiment. Two participants misunderstood the test task and were removed from data analyses. Twenty-three participants in each exposure group (Experiment vs. Control) were included in the analyses. All materials and procedure were identical to that in Experiment 2, except that now Speaker 4 served as the exposure talker.

Results

Exposure

Response accuracies were presented in Table B1. Accuracies for each type of words were comparable between the experimental group and the control group.

Test

Table B2 shows mean error rates and RTs in the test phase. Priming effects are shown in Fig. 4. Responses (5.1% of correct trials) above or below 2 SDs from the mean of each prime type in each exposure group were excluded from the RT analysis. The same mixed-effects model analyses were conducted as in Experiment 2. There was a significant priming effect (β = −26.02, SE = 2.94, p < .0001), a main effect of target type (β = 12.93, SE = 4.25, p < .01), and a marginally significant three-way exposure group × target type × prime type interaction (β = −3.88, SE = 2.12, p = .07). This interaction showed a trend that the exposure condition led to different priming patterns in the experimental group compared to the control group. Similarly, we examined whether the two groups’ performance changed over trials. There was a marginal Group × Trial effect (β = .08, SE = .04, p = .06) but no main effect of Trial or interactions with other predictors. Critically, including Trial as a predictor did not affect the exposure group × target type × prime type interaction (β = −4.06, SE = 2.13, p = .056). Because this interaction was of primary interest to the theoretical question whether acoustic similarity predicts talker generalization of phonetic retuning and was in line with our prediction, we continued to examine the priming patterns within each exposure group.

Figure 4.

Experiment 3 (Speaker 4 → Speaker 1) test results: Priming of /d/-final words (RT in fair-SEED trials minus RT in seed-SEED trials) and /t/-final words (RT in fair-SEAT trials minus RT in seed-SEAT trials) for participants exposed to critical words (Experimental group) or replacement words (Control group). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Similar to the control participants in the previous experiments, the control group showed equivalent priming for /d/-final and /t/-final words with no interaction between target type and prime type (β = 1.63, SE = 3.65, p = .66). In contrast, the experimental group showed significantly larger priming magnitude for /d/-final words than for /t/-final words (β = −7.62, SE = 3.78, p < .05), revealing evidence for cross-talker generalization of phonetic retuning. This result was in direct contrast with the results in Experiment 2: there, /d/-final words and /t/-final words were equally activated at the test phase, for experimental and control participants alike, indicating that having heard Speaker 2 producing critical /d/ words did not help listeners to recognize /d/ words from Speaker 1 any better.

Examining the lexical activations for each word type separately, we found that relative to the control group, the experimental group had significantly smaller priming for the /t/-final words (β = 5.79, SE = 2.74, p < .05) and numerically larger (non-significant) priming for /d/-final words (β = −2.05, SE = 3.25, p = .53). It appears that single-talker exposure led to dampened lexical support for the alternative interpretation (/t/-final words) and in this way reduced the amount of lexical competition that listeners experienced when hearing the ambiguous /d/. Notably, this particular pattern was not exactly the same as what was observed in Experiment 1, where multiple-talker exposure led to enhanced lexical support for the exposed ambiguous sound, but had no effect on the activation level of lexical competitors. We return to this point in the discussion.

As in Experiment 2, we analyzed whether participants’ response patterns differed as a function of their reports of talker and/or accent similarity (see Table B3 for descriptive statistics of voice and accent similarity ratings). Again, dividing participants based on their perception of “same versus different talkers” or “same versus different accents” did not reveal any statistically interpretable patterns and thus were not discussed here.

Across-experiments analysis

In Experiments 1 and 3, the perceptual learning effects as exhibited by group differences in priming patterns replicated the previous finding on talker-specific learning (Speaker 1 → Speaker 1, Xie et al., 2017): prior exposure to critical /d/ words significantly increased the degree of match between the auditory signal of other /d/-final words and their word forms (e.g., seed), making seat-like words a weaker lexical competitor to seed-like words and facilitated word recognition among the experimental group. We now statistically assess the effectiveness of accent adaptation and generalization under different exposure conditions: talker-specific exposure, single talker exposure, and multiple talker exposure. Pooling data across studies, we compared the learning effects among experimental participants elicited by talker-specific learning of Speaker 1 (Xie et al., 2017) to those elicited by an acoustically similar talker (Speaker 4; Experiment 3) and by a set of talkers (Multi 1 group; Experiment 1) in two mixed-effects models. Fixed effects included experiment, target type, prime type and full-scale interactions between these factors.

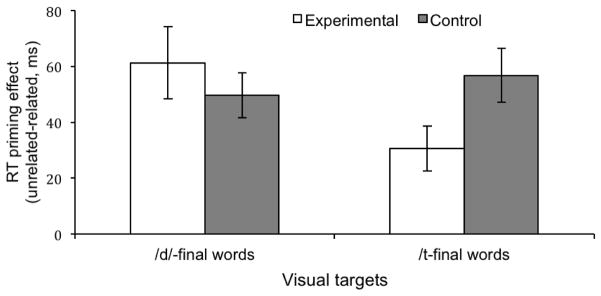

Results revealed a significant target type × prime type interaction (ps < .01) for both models, but neither model showed a further interaction with experiment (ps > .75). The results suggested that in all three conditions, the priming was larger for the /d/-final words than for /t/-final words, indicative of improved word recognition for Speaker 1 (Fig. 5). However, there was a marginally significant experiment-by-prime type interaction (p = .06) when participants in the talker-specific exposure were compared to those in multiple-talker exposure, driven by smaller priming (regardless of the target type) following multiple-talker exposure. In sum, reduced lexical competition was observed across the experiments, with the absolute priming effects being the largest following talker-specific exposure, and the smallest following multiple-talker exposure, and the single-talker exposure (Speaker 4 → Speaker 1) at the intermediate level.

Figure 5.

Test phase results across studies: talker-specific condition (Speaker 1 → Speaker 1, Xie et al., 2017), single-talker condition (Speaker 4 → Speaker 1, Experiment 3), multiple-talker condition (Multi 1 → Speaker 1, Experiment 1) and. Priming of /d/-final words (e.g., seed) and /t/-final words (e.g., seat) in the experimental group. In both related priming types, /d/-final words (e.g. seed) served as auditory primes. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Discussion

The results indicated that listeners were able to adapt to one talker (Speaker 4) and generalized the learning to another talker with similar acoustic patterns (Speaker 1): experimental participants showed attenuated lexical competition between /d/- and /t/-final minimal pairs, whereas control participants perceived the /d/ tokens to be highly ambiguous. Consistent with our hypothesis, cross-talker generalization was constrained by the inter-talker similarity in the productions of the critical segment. Of note, in both experiments 2 and 3, the exposure talker was of equivalent intelligibility to the test talker and both produced /t/-like /d/ words. As such, the contrast between Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 provided solid support to the ‘acoustic similarity’ hypothesis and reconciled existing findings that have demonstrated different talker generalization patterns. If two talkers produce a sound with sufficiently similar acoustic-phonetic distributions, then the adaptive learning elicited by prior experience of an accented talker could be better applied to a novel talker and helps listeners to generalize across talkers (Experiment 3), consistent with previous observation of ‘talker-independent’ adaptation for stop consonants (cf. Kraljic & Samuel, 2007); otherwise, perceptual learning appears to be talker-specific (Experiment 2).

In addition, the across-experiment comparison was informative about the efficacy of single talker exposure vs. multiple talker exposure in enhancing word recognition for a novel talker of the same foreign accent. Specifically, learning from a specific talker gave listeners the most benefit in word recognition; learning from an acoustically similar talker was also effective, whereas the overall priming was weaker following multiple-talker exposure, relative to talker-specific exposure. These results were different from the findings of Bradlow and Bent (2008). In Bradlow and Bent (2008), the learning effect was defined as an increase in word-level transcription accuracy. They trained participants with sentence-level non-native accented speech stimuli and established that the learning effect from multiple-talker exposure was as large as that from talker-specific exposure, whereas single-talker exposure failed to elicit cross-talker generalization. Our finding extended those of Bradlow and Bent (2008) by showing that multiple-talker exposure can facilitate, but is not necessary for talker generalization. It is highly plausible that listeners may have generalized perceptual learning from one talker to another in their study, but such generalization was not readily detectable in global intelligibility measures. In addition, even though multiple-talker exposure enhanced word recognition accuracy for a novel talker, that did not necessarily mean that listeners achieved this gain with equivalent ease as listeners who had experience with the specific talker. By zooming in on a specific category and examining adaptation effects following brief exposure, we showed that sensitivity to acoustic-phonetic distributions across speakers prepared listeners for generalization. It is reasonable to predict that when such processes scale up, listeners could adapt to multiple sound deviations simultaneously (perhaps with some cognitive cost) and achieve global improvement in accent perception, as shown in intelligibility studies.

One subtle difference between Experiment 1 and Experiment 3 is noteworthy: despite the fact that both showed reduced lexical competition among experimental participants, in Experiment 1 this was primarily achieved via increased lexical activation for target words, whereas in Experiment 3 this was achieved via decreased lexical activation for competitor words in addition to numerically elevated activation for intended targets. Spoken word recognition is a complex process that relies both on the activation of multiple candidate words, but also on the competition (via lateral inhibition) among them (e.g., Gaskell & Marslen-Wilson, 2002; Brouwer & Bradlow, 2016). It is difficult to conclude whether the relatively smaller activation for competitors in Experiment 3 was a result of weaker activation for these competing words per se, or non-exclusively, a result of lateral inhibition from the intended target. Existing evidence shows that listeners may penalize lexical competitors more or less, depending on a few linguistic and environmental factors such as word familiarity, listener proficiency and signal clarity (e.g., White et al., 2013; McQueen & Huettig, 2012). Possibly, adaptation not only improved the goodness of fit between accented input and stored lexical representations, but has somewhat changed the strength of inhibition on competitor words. If this is case, the reduced activation for competitors in Experiment 3 might reflect a stronger inhibition and could be indirect evidence for changes in activation threshold (i.e., after adaptation, lower activation of targets is needed to exert lateral inhibition). While our experiments were not designed to address the dynamics of word recognition and more explicit models are required for a full explanation, these results open questions for further exploration. Future studies may investigate the time course of spoken word recognition following accent adaptation, and in particular the interplay between lexical activation and lexical competition, to better understand adaptation effects.

General Discussion

Past research has reported rapid adaptation when native listeners encounter a speaker with an unfamiliar accent (e.g., Norris et al., 2003; Reinisch & Holt, 2014; Xie et al., 2017). Under what scenarios would listeners generalize such experience to novel talkers is unclear. In three experiments, we investigated talker generalization of phonetic adaptation in different talker exposure settings. Taken together, the results support the hypothesis that the degree of acoustic-phonetic similarity (of specific sound categories) among talkers modulates the degree to which phonetic retuning can be generalized across talkers. This account reconciles some inconsistent patterns in existing studies on talker accent adaptation, and applies well in different exposure conditions (i.e., exposure to one or multiple talkers).

There were two major findings. First, successful generalization of phonetic adaptation to a novel talker was predicted by the amount of acoustic similarity between the exposure talker(s) and the test talker, rather than the number of exposure talkers. Multiple-talker exposure can facilitate but is not necessary to elicit retuning of specific phonetic categories (cf. Bradlow and Bent, 2008). With the caveat that single-talker exposure rendered a weak three-way interaction between exposure group, word type and prime type in Experiment 3, there was no evidence that brief multiple-talker exposure provided a fundamentally different perceptual benefit that was not affordable by exposure to a single acoustically-similar talker. Specifically, if we take reduced lexical competition as a measure for improved word recognition, then both single-talker exposure and multiple-talker exposure were effective. Second, in both cases (single talker exposure and multiple talker exposure), explicit knowledge of talker identity or talker accents was not the decisive factor constraining generalization across talkers. Rather, bottom-up acoustic similarity between exposure and test talkers had direct consequences on talker generalization. Situating our results in the context of past findings, we offer answers to three important questions: 1) Why do listeners appear to generalize experience from one talker to another in some cases, whereas sometimes they do not? 2) Is there interplay between top-down expectations about the talker situation (e.g., who is speaking, how many talkers, what kind of accents) and bottom-up acoustic information in guiding talker generalization? 3) How do listeners move from talker-specific adaptation to general accent adaptation? We discuss our answers to these questions in turn.

Reconciling Existing Evidence: Generalization from One Talker to Another

Our findings make it clear that the different generalization patterns for stops versus fricatives (Kraljic & Samuel, 2005, 2007; Eisner & McQueen, 2005; Reinisch & Holt, 2014) are a by-product of bottom-up similarity in the segmental productions. For both types of phonemes, listeners do not generalize to novel talkers if the production pattern of specific phonemes from the new talker does not match their experience from a prior talker; furthermore, they readily generalize to a different talker if bottom-up similarity supports it. Specifically, our results further revealed that listeners were not merely assessing speaker similarity based on their overall intelligibility (as speakers were matched on this measure in Experiments 2 and 3), they were sensitive to fine-grained variation along multiple acoustic dimensions and a comparison of a talker’s acoustic-phonetic space to prior talkers constrained the interpretation of linguistic categories in the talker’s productions. In brief, generalization was predicted by talker similarity at the acoustic cue level, not at the global intelligibility level. This finding refined the notion of talker similarity in constraining generalization and placed the locus at the subphonemic level.

The Role of Top-Down Expectations of Accentedness on Generalization

This leads us to the second question: does acoustic similarity tell the whole story or is there a top-down influence from listeners’ explicit judgments of talker and accent similarity? Eisner and McQueen (2005) cross-spliced ambiguous fricative sounds produced by one speaker into an entirely new voice and observed a typical adaptation pattern for the ambiguous sounds, despite the fact that the new voice was perceptibly different. That is, the context of speech (or perceived voice) in which the critical segment was embedded did not matter. Reinisch and Holt (2014) found that listeners generalized their experience with a prior accented speaker to a novel speaker, despite the fact that the two speakers were identified as two individuals of different accents. In Experiment 2, we did not find evidence of generalization even among participants who believed they were listening to a single speaker the whole time. Even though we did not test it in the current study, a prediction compatible with an account of ‘similarity-based’ generalization is that listeners may potentially generalize beyond a particular accent, as evident in the learning of non-native phonetic contrasts in a foreign language (e.g., Moon & Sumner, 2013). However, this is not to say that similarity between old and new speech stimuli is the sole reason whether listeners generalize or not. It is possible that under more natural situations where listeners receive extraneous information about talkers’ accents, they could develop an explicit knowledge of the accent of speakers, and use it to actively predict incoming acoustic patterns and constrain generalization. That said, existing findings are consistent with a framework in which listeners build up conservative models to represent talker-specific phonetic categories and generalize only when talkers are sufficiently similar along the phonetically-relevant acoustic dimensions.