Abstract

Enhancing communication as a means of promoting relationship quality has been increasingly questioned, particularly for couples at elevated sociodemographic risk. In response, the current study investigated communication change as a mechanism accounting for changes in relationship satisfaction and confidence among 344 rural, predominantly low-income African American couples with an early adolescent child who participated in a randomized controlled trial of the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program. Approximately 9 months after baseline assessment, intent-to-treat analyses indicated ProSAAF couples demonstrated improved communication, satisfaction, and confidence compared with couples in the control condition. Improvements in communication mediated ProSAAF effects on relationship satisfaction and confidence; conversely, neither satisfaction nor confidence mediated intervention effects on changes in communication. These results underscore the short-term efficacy of a communication-focused, culturally sensitive prevention program and suggest that communication is a possible mechanism of change in relationship quality among low-income African American couples.

Keywords: African Americans, communication, confidence, mechanism, relationship education, satisfaction

Couple communication patterns are commonly viewed as critically important to couples’ relationships (e.g., Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) and thus form an essential component of nearly all couple and relationship education (CRE) programs designed to enhance romantic relationship outcomes (Halford & Snyder, 2012). Despite this widespread practice, several scholars recently have challenged the theoretical foundation and practical value of communication behaviors as a central target of programs designed to strengthen relationships, particularly for low-income racial and ethnic minority couples (e.g., Johnson & Bradbury, 2015; Lavner, Karney & Bradbury, 2016). Empirical evidence informing this debate, however, has remained somewhat limited. This scarcity of research is particularly evident involving randomized controlled trials (RCT) with ethnically diverse, low-income families (for exceptions, see Beach et al., 2014; Williamson, Altman, Hsueh, & Bradbury, 2016; Wood, Moore, Clarkwest, & Killewald, 2014). The current study was designed to address this gap. Using data from the first two waves of an RCT involving rural African American couples, we examined (a) the effect of the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program on couples’ communication, relationship satisfaction, and relationship confidence, and (b) patterns of mediation to provide prima facie evidence of the role of communication change as a conduit of programmatic effects on other facets of relationship functioning.

Recent Origins of the Controversy

Communication has a long history as an area of focus in relationship enhancement (e.g., Markman & Floyd, 1980) and an even earlier origin in social psychology (e.g., Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) that gave rise to applications in multiple areas. Its inclusion in the first generation of CRE programs was supported by longitudinal studies that suggested communication patterns (e.g., perceived positivity/negativity of communication during interactions) predates or exacerbates the development of marital distress and divorce (e.g., Markman, 1981). In recent years, the role of communication as a central mechanism for CRE program effects has been increasingly challenged. This scrutiny is based on research examining how external factors hinder adaptive relationship processes (e.g., Neff & Karney, 2009), mixed results from large-scale evaluation studies of CRE programs with low-income couples (e.g., Wood et al., 2014), and divergent results from studies examining communication as a mechanism of program effects on relationship quality (see Bradbury & Lavner, 2012). Specifically, previous studies have yielded results that confirm (Beach et al., 2014), provide null results (Williamson et al., 2016), or even contradict (Schilling, Baucom, Burnett, Allen, & Ragland, 2003) the hypothesis that gains in dimensions of couple communication predict improved relationship quality in CRE programs. A recent longitudinal study of low-income newlyweds found that communication positivity, negativity, and effectiveness rarely predicted changes in satisfaction, further challenging the central role of communication for relationship quality (Lavner et al., 2016). Moreover, results from this study indicated relationship satisfaction more commonly predicted changes in communication, thereby introducing the possibility that relationship satisfaction may be a mechanism for change in communication. This direction of effect, however, has yet to be tested using experimental data.

Although previous studies have not consistently supported communication change as a causal mechanism leading to broader changes in relationship satisfaction, two important qualifications must be noted. First, in some studies, levels of relationship satisfaction were measured many months after assessing communication (e.g., 18 months in Williamson et al., 2016). Although representing a strength in some respects, a long lag time between assessments of communication and relationship satisfaction also introduces the possibility for third-variable effects and intervening life changes to confound or dilute tests of mediation. In addition, improving communication in the short-term may be of value given its ability to produce a cascade of positive effects with longer-term outcomes (e.g., Beach et al,. 2014).

Second, studies that suggest communication is not a mechanism of CRE program effects on relationship quality (e.g., Williamson et al., 2016; Schilling et al., 2003) have included a relatively small percentage of African American couples (≤ 10%). Although the underlying reasons have not been examined, previous research has suggested that African American couples may exhibit a more positive response to communication-focused CRE programs than do couples of other ethnic groups (Stanley et al., 2014), highlighting the need to tailor, modify, or contextualize community-based CRE programs to be more culturally sensitive and relevant to maximize engagement and retention with African American couples (Ooms & Wilson, 2004). Previous communication-focused CRE programs designed for African American couples have been found to promote effective communication and enhance relationship quality (Beach et al., 2011; Beach et al., 2014). Thus, examination of the mediating effects of communication may produce somewhat different (i.e., stronger) results using an African American sample.

ProSAAF and the Current Study

Most research devoted to African American families, both basic and applied, has focused on parent-child relations in single-mother-headed households (e.g., Brody et al., 2004; Jones, Zalot, Foster, Sterrett, & Chester, 2007). As a result, far less research and programming have been devoted to strengthening two-parent African American families (for exception, see Beach et al., 2014). In response, the ProSAAF program was developed to promote couple, family, and youth well-being among two-parent African American families with an early adolescent child who resided in resource-poor areas of the rural southern United States (US). In this six-session, in-home program, programmatic instruction focuses primarily on parents, with youth involved in only the final 30 minutes of each 2-hour session. Specific couple issues targeted in the program include positive relationship processes, daily hassles and burdens, and communication skills, particularly active listening and recognizing that emotional states may compromise listening. Each session begins with a focus on a particular domain of stress that African American couples experience (e.g., finances, racism, extended family), and couples are instructed in cognitive and behavioral strategies for handling stressors, with particular emphasis given to partners’ use of enhanced communication with one another in response to daily stressors. Feedback from formal and informal focus groups led to refined language use, increased attention to positive racial socialization, and a refined focus on issues seen as important in local community contexts.

The current study was designed with two main aims in mind. First, we examined the short-term efficacy (i.e., 9 months following randomization) of ProSAAF to enhance African American couples’ effective relationship communication, relationship satisfaction, and confidence in the future of their relationships (relationship confidence). The inclusion of relationship confidence as an outcome, rather than only including satisfaction, is particularly valuable given research questioning the prioritization of satisfaction in cultural and academic thinking about romantic relationships and instead calling for greater attention to constructs that may be equally (or more) important for relationship quality (e.g., Barton & Bishop, 2014), including individuals’ confidence and hope in the future of their relationship (Erickson, 2015). Second, we addressed, experimentally, a question regarding mechanisms of change in relationship quality. Addressing the question of mechanisms of change in relationship quality for African American couples has both theoretical and practical importance, including the development of inclusive theories of relationship development and change, the construction of more effective relationship enhancement programs, and the need to understand better racial and socioeconomic disparities in relationship outcomes. As previously noted, one impediment to the development of preventative interventions for couples, including low-income African American couples, is a lack of consensus regarding key mechanisms of change that can promote relationship quality in this population. Thus, we sought to determine whether changes in communication mediate intervention effects on relationship satisfaction and confidence, or conversely, whether changes in satisfaction or confidence mediate intervention effects on communication.

METHOD

Participants

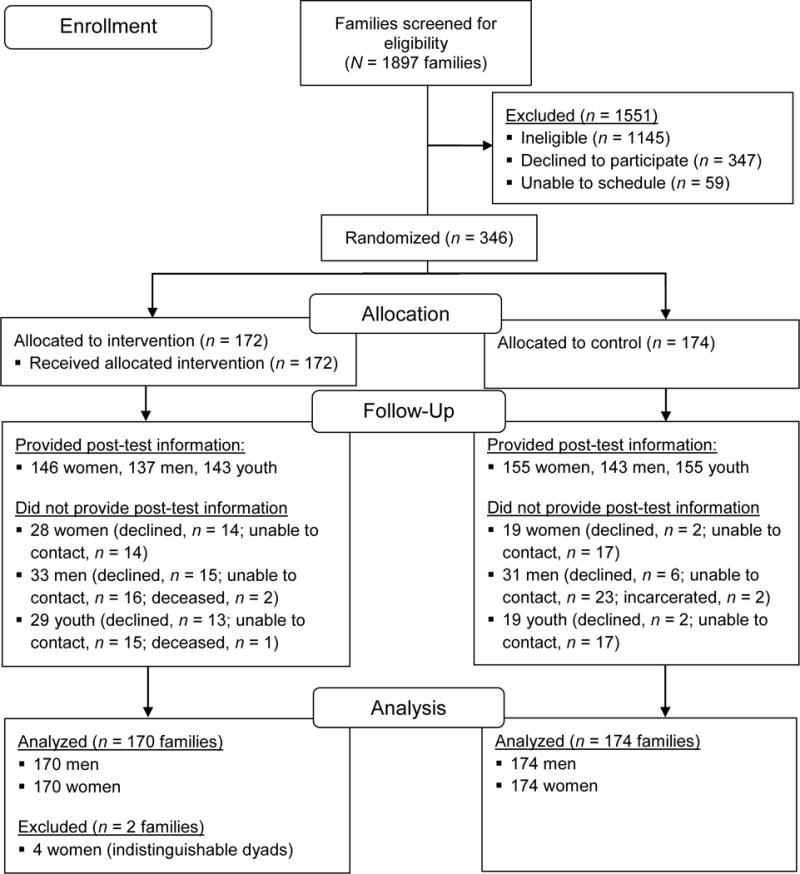

Participants in the study were African American couples with an early adolescent child who lived in low-income communities in rural Georgia. A total of 1897 families, recruited from school lists and through advertisements, were screened for eligibility. Of these 1897 families, 1145 were ineligible because they were a single-parent household, the family was enrolled in another program, the child was not within the age parameters, or the child was not African American. Of the remaining 752 families who met eligibility criteria, 347 were not interested in participating (i.e., did not respond to the solicitation) and 59 families were unable to schedule an assessment. The remaining 346 families were randomized to the intervention (n = 172) or control (n = 174) conditions. Two same-sex couples were excluded from analyses because the small sample size precluded comparisons with this group. The percentage of participating families out of the initial screening group (18.2%) compares favorably to participation rates in other samples of low-income couples (e.g., 11.4% in Lavner et al., 2016), and the percentage of families meeting eligibility criteria who participated in the intervention (46.0%) is comparable to participation rates among eligible families in other trials of relationship education targeting select demographics (e.g., 47.6% among military couples in Stanley et al., 2014).

Of the randomized couples, 63% were married, with a mean length of marriage of 9.7 years (range < 1 year – 56 years). Unmarried couples had been living together an average of 6.75 years (range < 1 year – 24 years). Men’s mean age was 39.73 years (range 21 – 83) and women’s mean age was 36.54 years (SD = 7.45; range 23 – 73). Men’s median education level was high school or GED (ranging from less than grade 9 to a doctorate or professional degree), and women’s median education level was some college or trade school (ranging from less than grade 9 to a master’s degree). The majority of men (74.1%) and women (61.0%) reported being employed. Median monthly income was $1,400 (range $1 – $7,500) for men and $1,270 (range $1 – $8,900) for women. Fifty-two percent of families had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level and 69% had incomes below 150% of the federal poverty level. The total number of children residing in the home ranged from 1 to 8, with median of 3 and mode of 2.

Procedures

Families were informed about the study by mail and phone from school lists as well as through study advertisements. To be eligible, couples had to be in a relationship for 2 years or more, living together, and co-parenting an African American child between the ages of 10 and 13 years for at least 1 year. Couples had to be willing to spend 6 weeks engaged in a CRE program and not be planning to move out of the study area during the study period. Eligible families who were interested in participating were assigned randomly to the treatment or information-only control condition following completion of pretest measures. Block randomization by marital status was performed within each county to help facilitate group equivalence. Project staff visited couples’ homes, explained the study in more detail, and obtained participant consent and, for youth, minor assent. Parents and youth then completed the pretest (Wave 1) assessment. The posttest (Wave 2) assessment was completed a mean of 9.4 months after pretest (a mean of 6.3 months following the conclusion of the program for families in the intervention condition). Figure 1 illustrates participant progress through the first two waves of the study. Adults were compensated with a $50 check and youth with a $20 gift card for completing each wave of data collection. Study attrition (instances in which no family member participated in the posttest assessment) was 13.6% and did not vary by condition. Data were collected between 2013 and 2015 in rural counties throughout the state of Georgia.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT FLOW DIAGRAM.

ProSAAF implementation

A trained African American facilitator visited each couple’s home on an approximately weekly basis for 6 consecutive weeks and facilitated a 2-hour session with coparenting adults and children. Families were offered six primary sessions, with 81% of the families participating in all six sessions, 9% attending between 1–3 sessions, and 9% attending no sessions. The facilitator guided couples through video instruction and modeling, structured activities, and discussion of specific topics. To reinforce material covered during the main course of instruction, a booster session was offered approximately 3 months after program completion and 3 months before posttest assessment; 74.4% of intervention families participated (see Markman & Rhoades (2012) and Braukhaus, Hahlweg, Kroeger, Groth, & Fehm-Wolfsdorf (2003) for additional discussion regarding booster sessions and CRE).

Control group

After pretest, couples in the information-only control group were mailed the book 12 Hours to A Great Marriage (Markman, Stanley, Blumberg, Jenkins, & Whaley, 2004) and an accompanying workbook. All couples were assessed on the same schedule.

Measures

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was measured using the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983). This six-item scale measures global perceptions of relationship satisfaction using a 5-point Likert scale, where lower scores indicate a more negative evaluation. Reliability was acceptable at all assessments (men: α = .92 at pretest and .94 at posttest; women: α = .93 at pretest and α = .96 at posttest).

Relationship confidence

Individuals rated the confidence in the future of their relationship using four items from the Relationship Confidence Scale (RCS; Allen, Rhoades, Markman, & Stanley, 2015; Stanley, Hoyer, & Trathen, 1994). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (sample item: “I am very confident when I think of my future with [partner name]”. Reliability was acceptable at all assessments (men: α = .87 at pretest and .93 at posttest; women: α = .91 at pretest and .91 at posttest).

Communication

Participants’ reports of effective communication were measured using an eight-item version of the Communication Skills Test (CST; Jenkins & Saiz, 1995) and a 10-item Communication and Stress Scale (CSS) developed for ProSAAF. The eight items from the CST, rated on 4- and 7-point Likert scales, examined effective communication patterns (e.g., collaboration, perspective-taking, solution-focused efforts) within the couple (items standardized prior to computing mean; sample item: “When discussing an issue, my mate and I both take responsibility to keep us on track”). The 10 items from the CSS, rated on a 4-point Likert scale, examined effective communication about individual and couple stressors (sample item: “I try to notice if I am in a bad mood before I talk to [my partner] about important issues”). Higher scores reflect more effective communication. Reliability for both measures was acceptable at all assessments (for the CST: men: α = .83 at pretest and .90 at posttest; women: α = .86 at pretest and .90 at posttest; for the CSS: men: α = .86 at pretest and .88 at posttest; women: α = .87 at pretest and .88 at posttest).

Confirmatory factor analyses (available from first author) involving relationship satisfaction, relationship confidence, and communication at baseline supported a 3 factor solution for both men and women.

Treatment Fidelity

All sessions were audiotaped in order to monitor implementation. A sample of sessions was coded for adherence to intervention guidelines, with 20% coded by more than one rater. All facilitators were represented in the sample of tapes rated. The intraclass correlation between raters was .98. Mean fidelity adherence across facilitators was 92.1% (SD = 6.9%).

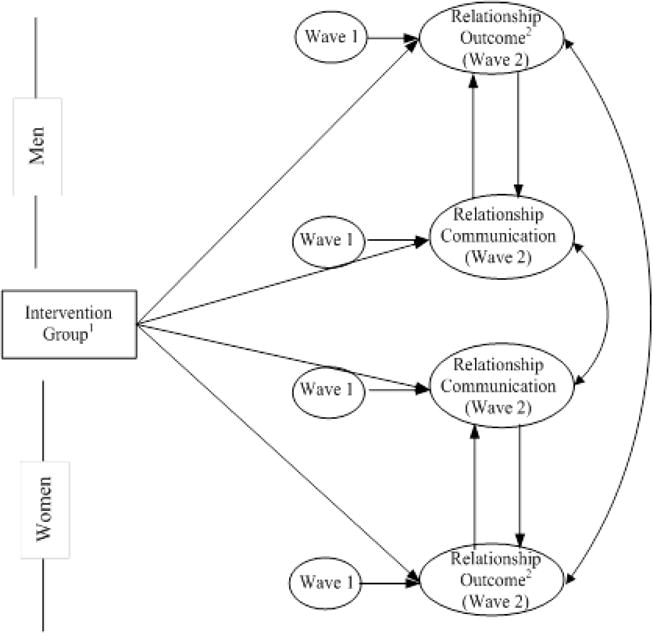

Plan of Analysis

Analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus version 7.4 using maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). After assessing group equivalence on sociodemographic measures and study variables, we ran three different models (one for each targeted outcome) to test intervention effects at posttest, controlling for pretest levels of variables for individuals and their spouses; corresponding variables from male and female partners were correlated to account for the dyadic nature of the data. Communication, satisfaction, and confidence were modeled as latent variables to account for measurement error. To determine whether intervention-induced changes in communication mediated changes in other areas of the relationship (or vice versa), we constructed two recursive models (see Figure 2): one model examined the associations among ProSAAF participation, effective communication, and relationship satisfaction, and the second model examined the associations among ProSAAF participation, effective communication, and relationship confidence. Marital status was tested as a moderator. Mediation was tested by fixing the direct path to zero and comparing model fit with the freely estimated model; a non-significant chi-square value would indicate full mediation. We calculated indirect effects (IEs) using bias-corrected bootstrapped sampling with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (Hayes, 2009). Given the binary nature of the independent variable, effect sizes (f2) of ProSAAF on relationship outcomes were computed by dividing the unstandardized coefficient (B) by the standard deviation of the dependent variable. Analyses were conducted according to an intent-to-treat approach in which all couples assigned to ProSAAF, regardless of program attendance, were compared to all couples assigned to the control group. Missing data were minimal (< 8% on all variables used in modeling) and were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation.

FIGURE 2.

CONCEPTUAL MODEL TESTING DIRECTIONS OF PROGRAM EFFECTS.

1 1 = Assigned to ProSAAF. 2 Relationship satisfaction tested as outcome in Model 2.1; relationship confidence tested as outcome in Model 2.2. Correlations between Wave 1 measures and indicators of latent variables are not shown for purposes of clarity.

RESULTS

Equivalence analyses were conducted to verify similarity of couples in the intervention and control conditions (see Supplemental Table S1). No differences between conditions were observed at pretest for family characteristics such as age, education, marital status, and income, or for study variables of relationship communication, satisfaction, and confidence. Supplemental Table S2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables.

Program Effects

We first tested the effect of the ProSAAF intervention on relationship communication, satisfaction, and confidence (Models 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, respectively) approximately 9 months after Wave 1. As shown in Table 1, the ProSAAF intervention had a significant effect on effective communication for both men and women. ProSAAF effects on relationship satisfaction were significant for men and approached statistical significance for women. Relationship confidence demonstrated a significant program effect for women and approached statistical significance for men. In each instance, greater gains were observed in ProSAAF couples.

Table 1.

Direct Effects of ProSAAF on Effective Communication, Relationship Satisfaction, and Relationship Confidence (N = 344 dyads)

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | B | se | β | p | f2 | B | se | β | p | f2 |

| Effective Communication (Model 1.1) | ||||||||||

| Intervention1 | 1.49** | .58 | 0.14 | .01 | .28 | 1.61** | .52 | 0.16 | .00 | .32 |

| Pretest, self | 0.65** | .09 | 0.59 | .00 | 0.81** | .09 | 0.74 | .00 | ||

| Pretest, partner | 0.07 | .08 | 0.06 | .41 | −0.08 | .07 | −0.07 | .25 | ||

| Relationship Satisfaction (Model 1.2) | ||||||||||

| Intervention | 0.17* | .08 | 0.11 | .04 | .23 | 0.16† | .09 | 0.10 | .06 | .18 |

| Pretest, self | 0.53** | .08 | 0.46 | .00 | 0.54** | .07 | 0.50 | .00 | ||

| Pretest, partner | 0.01 | .06 | 0.01 | .91 | 0.12 | .08 | 0.09 | .13 | ||

| Relationship Confidence (Model 1.3) | ||||||||||

| Intervention | 0.15† | .08 | 0.11 | .05 | .23 | 0.16* | .08 | 0.11 | .04 | .23 |

| Pretest, self | 0.47** | .08 | 0.41 | .00 | 0.39** | .06 | 0.42 | .00 | ||

| Pretest, partner | 0.12* | .05 | 0.13 | .03 | 0.10 | .08 | 0.08 | .22 | ||

Note. 1 = ProSAAF group assignment (0 = Control group assignment). Model fit statistics: Model 1.1: χ2(16) = 14.29, ns; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 [0.00, 0.05]; Probability RMSEA ≤ .05 = 0.97. Model 1.2: χ2(256) = 392.87, p < .01; CFI = .98; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .03 [0.03, 0.05]; Probability RMSEA ≤ .05 = 0.98. Model 1.3: χ2(112) = 226.53, p < .01; CFI = .97; TLI = .96; RMSEA = .06 [0.04, 0.07]; Probability RMSEA ≤ .05 = 0.23. Estimated sample means of latent variables for men (women) at wave 2: Communication: 0.74 (0.80); Satisfaction: 0.09 (0.08); Confidence: 0.07 (0.08). Wave 1 means of latent variables are zero when calculated in Mplus. Factor loading indicators for all latent factors: 0.583 ≤ λ ≤ 0.943.

p < .10, two-tailed.

p ≤ .05, two-tailed.

p ≤ .01, two-tailed.

Mechanisms of Change

We then tested whether program-related changes in communication mediated the effect of the intervention on relationship satisfaction and relationship confidence or, conversely, whether program-related changes in relationship satisfaction or relationship confidence mediated the effect of the intervention on relationship communication. As illustrated in Figure 2, we ran two SEM path analysis models, with one model testing the direction of association between communication and satisfaction (Model 2.1) and the other model testing the direction of the association between communication and confidence (Model 2.2)

In Model 2.1, ProSAAF effects on increases in relationship satisfaction were not significant for men (β = .06, ns) or women (β = .04, ns) after controlling for posttest levels of communication. ProSAAF effects on communication, however, remained significant after controlling for posttest satisfaction for both men (β = .10, p < .05) and women (β = .14, p < .01). In Model 2.2, ProSAAF effects on increases in confidence were not significant for men (β = .02, ns) or women (β = .04, ns) after controlling for posttest levels of communication. ProSAAF effects on communication, however, remained significant after controlling for posttest confidence for both men (β = .14, p < .05) and women (β = .14, p < .01). Thus, the effects of ProSAAF on communication remained significant in models that also controlled for posttest levels of satisfaction and confidence, respectively. ProSAAF effects on satisfaction and confidence, however, were not significant after controlling for posttest levels of communication.

Model fit comparisons further confirmed the full mediation effect through communication. Specifically, for models including communication as a mediator, there was not a significant decrement in chi-square from the baseline model when systematically constraining to zero the effect of ProSAAF on men’s satisfaction (Δχ2(1) = 1.46, p = .23), women’s satisfaction (Δχ2(1) = 0.586, p = .44), men’s confidence (Δχ2(1) = 0.159, p = .69), and women’s confidence (Δχ2(1) = 0.911, p = .34). Because the results indicated mediation by communication, IE analyses were conducted to quantify this effect empirically (tabulated results in supplemental table S3). Results indicated significant IEs through posttest communication for both relationship satisfaction (men: IE = 0.055; 95% CI: [.001, .146]; women: IE = 0.073; 95% CI = [.011, .173]) and relationship confidence (men: IE = 0.099; 95% CI: [.022, .245]; women: IE = 0.073; 95% CI = [0.013, 0.189]). In contrast, results indicated no significant IE through posttest satisfaction (men: IE = 0.255; 95% CI: [−.171, .991]; women: IE = 0.165; 95% CI = [−.242, .815]) or posttest confidence (men: IE = 0.029; 95% CI: [−.103, .406]; women: IE = 0.134; 95% CI = [−.133, .579]) on communication. This pattern held for both men and women. For IEs through communication, additional analyses indicated no significant sex differences in IE magnitudes for relationship satisfaction (contrast = 0.02, p = .66) or relationship confidence (contrast = −0.03, p = .60). These results suggest that, for men and women, ProSAAF increased relationship satisfaction and confidence by improving couples’ communication. They also suggest that the effect of ProSAAF on couples’ communication did not occur through pathways related to program-related improvements in relationship satisfaction or confidence.

Moderation by Marital Status

Ancillary analyses were conducted to determine if couples’ marital status moderated intervention effects on couples’ relationship communication, satisfaction, and confidence. These analyses were tested using a multigroup SEM approach by sequentially constraining paths to be equivalent across ProSAAF and control groups and comparing fit to unconstrained two-group model as well as by adding marital status and a ProSAAF × Marital status interaction as predictors in SEM models. No significant differences in ProSAAF effects based on couples’ marital status emerged from either set of analyses (results available from first author).

DISCUSSION

The ability to promote relationship quality among low-income couples through programs that target communication has been increasingly challenged. To inform this discussion as it pertains to African American couples, the current study examined the short-term effect of the newly-developed ProSAAF program on couples’ self-reported relationship communication, satisfaction, and confidence and accompanying mechanism for this effect. Program-induced improvements in each of these domains were apparent several months post-treatment. Results indicated that changes in communication attributable to the intervention mediated ProSAAF effects on both relationship satisfaction and confidence, suggesting that programs such as ProSAAF that include a focus on communication may help to improve relationship dynamics among African American couples dealing with socioeconomic and race-related challenges.

The finding that communication mediated intervention effects on relationship quality is consistent with previous clinical research in which therapy-induced changes in observed communication were linked to improvements in wives’ marital satisfaction (Baucom, Sevier, Eldridge, Doss, & Christensen, 2011), as well as with prospective research in which negative communication predicted increases in marital dissatisfaction over time (e.g., Smith, Ciarrochi, & Heaven, 2008). This finding also contrasts with recent research in which improvements in communication did not mediate intervention-related changes in low-income couples’ relationship satisfaction (Williamson et al., 2016). The findings also do not support the hypothesis that program-related changes in relationship satisfaction or relationship confidence predict change in communication. Thus, despite obvious difficulties in isolating the source of impact for any multicomponent preventive intervention (Markman & Rhoades, 2012), the current results support a priori expectations that enhanced communication would be important for this sample.

Differences between our results and the results of some other studies (e.g., Schilling et al., 2003; Williamson et al., 2016) highlight pertinent methodological issues pertaining to research and evaluation of CRE programs and their effects. The current study used self-report measures of effective communication, which may show different patterns of association with satisfaction over time compared to observational measures (e.g., Lavner et al., 2016; Williamson et al., 2016). Self-reported communication may better capture the effect of support and problem solving in context, something that is often difficult to reconstruct using observational measures and thus better capture the hypothesized “mechanism” of change (e.g., feeling listened to, attended to, respected, safe, and on the same side as one’s partner) than does observed communication, which may not translate as well into an “experience of better communication” (also see Williamson et al., 2016). Conversely, shared method variance could overinflate the association of self-reported communication with self-reported satisfaction. Secondly, variability in the measurement of relationship satisfaction can also confound findings across studies. In the current study, satisfaction was assessed using the well-validated QMI measure. Williamson and colleagues used a measure of satisfaction that included a more heterogeneous set of items (e.g., support, friendship). This difference between a focus on relationship evaluations versus a composite of skills, processes, and evaluations in measures intended to assess “relationship satisfaction” could lead to diverging conclusions, a problem rife in couples research that has been described elsewhere (e.g., Fincham & Rogge, 2010).

Conflicting findings may be attributable to the different contexts and content of CRE interventions. In contrast to most CRE programs, ProSAAF was specifically developed to be culturally sensitive to African American couples living in impoverished regions of the southern US and to address common shared challenges confronting rural African American couples raising youth together (e.g., finances, discrimination, parenting). Communication techniques were implemented in this context and were taught and practiced in relation to specific stressful experiences; this approach may better facilitate African American couples’ application of communication training messages to their own lives in ways that are less likely with generic principles that might not be as well suited to the circumstances and stressors that low-income families encounter. Finally, pathways of influence between communication and relationship satisfaction in the present study focused on concurrent associations, whereas mediated effects in Williamson et al. (2016) were examined at an 18-month interval. Different conclusions can be drawn from studies using concurrent versus longer-term assessments of the association between communication and relationship satisfaction. Mechanisms such as self-reported communication may be expected to produce immediate effects on certain relationship outcomes and may best be tested concurrently or after a relatively short interval. Conversely, other processes such as trust or relationship efficacy may only begin to exert an effect after cumulative presence over time, and thus may be better tested using models with longer intervals. Accordingly, both concurrent and lagged analyses can contribute to an understanding of the role of communication and other couple processes in CRE effectiveness, while also suggesting results may differ depending on the length of the lag. Further research examining these methodological issues would be valuable.

Several limitations of the current investigation should be noted. First, the results pertain only to short-term program impact; additional time points are needed to assess the degree to which change is maintained over time and to permit growth curve analyses to identify better within-person change. Second, our communication measures largely focused on one type of behavior, effective communication, and not other forms of communication that may also influence relationships (e.g., positivity, negativity; demand/withdraw) and have been examined in other studies (e.g., Lavner et al., 2016; Stanley et al., 2007). Third, the study design did not allow us to test program effects with and without the booster session. Fourth, participants in both treatment and control condition may have been more motivated to strengthen their relationship than population at large; concerns of the potential influence of participant characteristics on results, however, are abated given the randomization of participants to both conditions. Fifth, with the exception of marital status, the current study was designed to focus exclusively on mediational pathways. Future research can examine variability in program effects by potential moderators. In particular, future research should investigate the ways in which contextual adversity may moderate the impact of the intervention overall and impact the association between communication and satisfaction (e.g., Williamson et al., 2016). As one final important consideration, the current study concentrated primarily on couple process variables. Given the nature of the sample, it is important to also consider structural issues linked to social, economic, and historic factors that infringe in systematic and profound ways on the life chances of lower-income African American families. A strength of the ProSAAF program is its incorporation of structural and contextual issues into prevention programming for low-income ethnic minority couples. Future research of the ProSAAF program is planned to more fully expand on these points and to investigate empirically the influence of both structural and process variables that have important implications for research and practice.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current study provides timely results to inform the ongoing discussion about CRE programs targeted to low-income African American couples. Results indicate that an empirically based, culturally sensitive CRE program for African American couples residing in low-income communities can exert positive change in multiple relationship dimensions and the intermediary role of improved effective communication. Thus, current results indicate that communication skills constitute a useful, although not exclusive, focus for interventions designed to promote couple relationship quality among African Americans living in the rural South. We agree with recommendations from other scholars that the current state of the literature warrants a re-evaluation of the central tenets that have informed CRE efforts to date (see Johnson & Bradbury, 2015), including a renewed focus on theoretically and substantively meaningful processes that may have been overlooked (e.g., gratitude, couple social integration; see Barton, Futris, & Nielsen, 2014; 2015)) and more transdisciplinary approaches to interventions that target relational, vocational, and financial domains (Lavner et al., 2015). Results of these efforts can then inform refined prevention programs that help low-income couples protect their relationships from the deleterious effects of contextual stressors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by award R01 HD069439 funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by award P30 DA027827 funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Eileen Neubaum-Carlan for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this article. We also thank the families for their willingness to participate in this research

References

- Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ, Stanley SM. PREP for Strong Bonds: A review of outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2015;37(3):232–246. doi: 10.1007/s10591-014-9325-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Bishop RC. Paradigms, processes, and values in family research. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2014;6(3):241–256. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Futris TG, Nielsen RB. With a little help from our friends: couple social integration in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(6):986. doi: 10.1037/fam0000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Futris TG, Nielsen RB. Linking financial distress to marital quality: The intermediary roles of demand/withdraw and spousal gratitude expressions. Personal Relationships. 2015;22(3):536–549. doi: 10.1111/pere.12094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom KJW, Sevier M, Eldridge KA, Doss BD, Christensen A. Observed communication in couples two years after integrative and traditional behavioral couple therapy: Outcome and link with five-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:565–576. doi: 10.1037/a0025121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Hurt TR, Fincham FD, Franklin KJ, McNair LM, Stanley SM. Enhancing marital enrichment through spirituality: Efficacy data for prayer focused relationship enhancement. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2011;3:201–216. doi: 10.1037/a0022207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Barton AW, Lei MK, Brody GH, Kogan SM, Hurt TR, Stanley SM. The effect of communication change on long-term reductions in child exposure to conflict: Impact of the Promoting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) Program. Family Process. 2014;53:580–595. doi: 10.1111/famp.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Lavner JA. How can we improve preventive and educational interventions for intimate relationships? Behavior Therapy. 2012;43:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braukhaus C, Hahlweg K, Kroeger C, Groth T, Fehm-Wolfsdorf G. The effects of adding booster sessions to a prevention training program for committed couples. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;31:325–336. doi: 10.1017/S1352465803003072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, Neubaum-Carlan E. The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(2):101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SE. Masters thesis. 2015. Got Hope? Measuring the Construct of Relationship Hope with a Nationally Representative Sample of Married Individuals. Retrived from BYU ScholarsArchive. Paper 5322. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Rogge R. Understanding relationship quality: Theoretical challenges and new tools for assessment. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2010;2:227–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Snyder DK. Universal processes and common factors in couple therapy and relationship education. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins NH, Saiz CC. The Communication Skills Test. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Bradbury TN. Contributions of social learning theory to the promotion of healthy relationships: Asset or liability? Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2015;7:13–27. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Zalot A, Foster S, Sterrett E, Chester C. A review of childrearing in African American single mother families: The relevance of a coparenting framework. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:671–683. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9115-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. New directions for policies aimed at strengthening low-income couples. Behavioral Science and Policy. 2015;1(2):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Does couples’ communication predict marital satisfaction, or does marital satisfaction predict communication? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78:680–694. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ. Prediction of marital distress: A 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:760–762. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.49.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Floyd F. Possibilities for the prevention of marital discord: A behavioral perspective. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1980;8:29–48. doi: 10.1080/01926188008250355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Rhoades GK. Relationship education research: Current status and future directions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:169–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Stanley SM, Blumberg S, Jenkins NH, Whaley C. Twelve hours to a great marriage. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, editors. Mplus user’s guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:435–450. doi: 10.1037/a0015663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1983;45:141–151. doi: 10.2307/351302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms T, Wilson P. The challenges of offering relationship and marriage education to low-income populations. Family Relations. 2004;53:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Baucom DH, Burnett CK, Allen ES, Ragland L. Altering the course of marriage: the effect of PREP communication skills acquisition on couples’ risk of becoming maritally distressed. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:41–53. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Ciarrochi J, Heaven PCL. The stability and change of trait emotional intelligence, conflict communication patterns, and relationship satisfaction: A one-year longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Hoyer L, Trathen DW. The Confidence Scale. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Loew BA, Allen ES, Carter S, Osborne LJ, Markman HJ. A randomized controlled trial of relationship education in the U.S. Army: 2‐year outcomes. Family Relations. 2014;63:482–495. doi: 10.1111/fare.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut JW, Kelley HH. The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson HC, Altman N, Hsueh J, Bradbury TN. Effects of relationship education on couple communication and satisfaction: A randomized controlled trial with low-income couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84:156–166. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RG, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, Killewald A. The long-term effects of Building Strong Families: A program for unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76:446–463. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.