Abstract

Protein kinases transduce signals to regulate a wide array of cellular functions in eukaryotes. A generalizable method for optical control of kinases would enable fine spatiotemporal interrogation or manipulation of these various functions. Here, we report the design and application of single-chain cofactor-free kinases with photoswitchable activity. We engineered a dimeric protein, pdDronpa, that dissociates in cyan light and reassociates in violet light. Attaching two pdDronpa domains at rationally selected locations in the kinase domain, we created photoswitchable kinases psRaf1, psMEK1, psMEK2 and psCDK5. Using these photoswitchable kinases, we established an all-optical cell-based assay for screening inhibitors, uncovered a direct and rapid inhibitory feedback loop from ERK to MEK1, and mediated developmental changes and synaptic vesicle transport in vivo using light.

Kinase-mediated phosphoryation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues is a widespread mechanism of protein regulation, occurring on 40% of eukaryotic proteins (1). As downstream responses often depend on the location, amplitude, and duration of protein phosphorylation (2, 3), methods to control kinases in space and time would aid in understanding signal transduction input-output relationships and in predicting therapeutic utility of kinase modulation in disease. Optical control of protein activity can achieve high spatiotemporal resolution that would not be possible with pharmacological or conventional genetic methods. A variety of natural photosensory domains have been used to achieve optical control of protein activity via relocalization (4–12), sequestration (13, 14), fragment complementation (7, 15), induced avidity or concentration (16–18), or allostery (19–23). Optical activation of certain serine/threonine/tyrosine kinases has been achieved by relocalization to the plasma membrane and of certain receptor tyrosine kinases by clustering (Fig. S1A,B)(24–29). Optical inhibition of kinases has also recently been reported (Fig. S1C) (19). However, a generalizable design for single-chain light-activatable kinases that can function regardless of subcellular location has not previously been described.

To link optical inputs with kinase activity, we envisioned modular single-chain protein architectures that undergo large conformational changes in response to light. We hypothesized that we could genetically attach dimerizing domains at two locations flanking a kinase active site so that the intramolecular dimer would sterically hinder substrate access at baseline, thereby caging the kinase. If the dimerizing domains were photodissociable, then illumination would convert the polypeptide into an open conformation and induce kinase activity (Fig. S1D). As no natural dimeric domains are dissociated by visible light, we engineered one from the photodissociable tetrameric green fluorescent protein (FP) DronpaN145 (30). By rationally introducing mutations to break the anti-parallel dimer interface, strengthen the cross dimer interface in Dronpa N145, and improve maturation, we created a photodissociable dimeric Dronpa domain, pdDronpa1 (Figs. S2–S3, Supplementary Note). Like its parent DronpaN145, pdDronpa1 was photodissociated and its fluorescence switched off by 500-nm cyan light, and photoassociated and its fluorescence restored by 400-nm violet light (Fig. 1A). Conveniently, pdDronpa1 was brighter than DronpaN145 in mammalian cells (Fig. S4A) but required less light for off-photoswitching (Fig. S4B). Fusion of two copies of pdDronpa1 to a protein of interest also caused less aggregation in cells compared to Dronpa N145 (Fig. S4C). pdDronpa1 has a dissociation constant (Kd) of 4.0 μM as measured by analytical ultracentrifugation (Table S2), suitable for intramolecular dimerization (31).

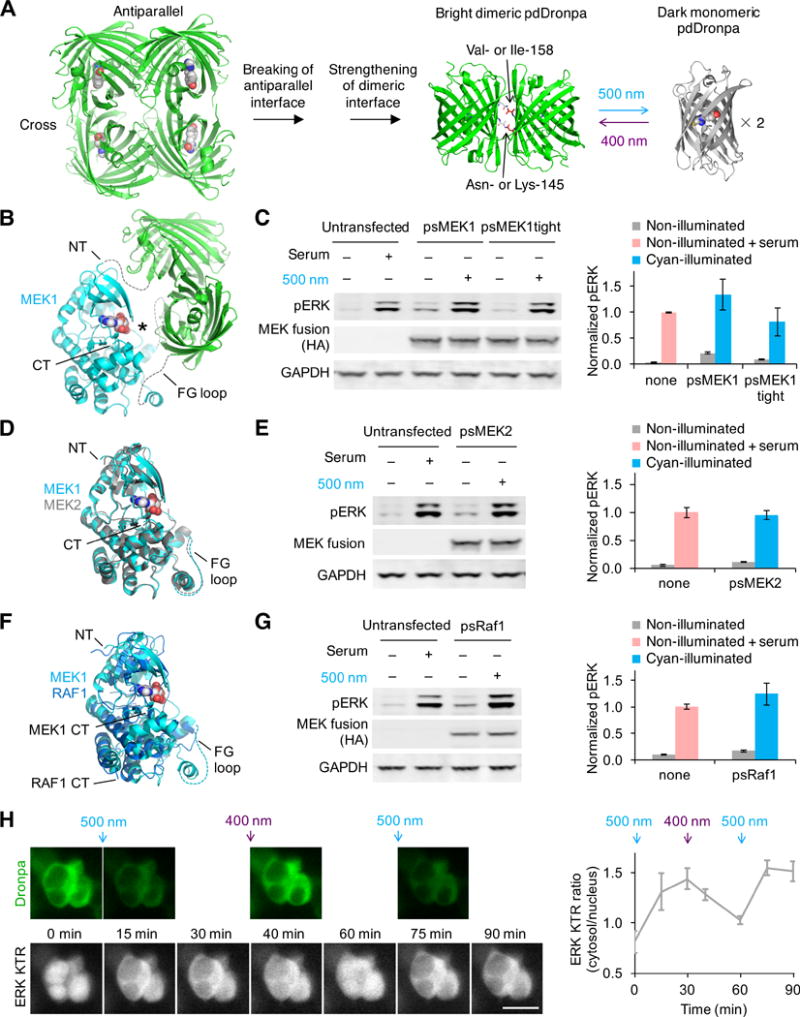

Fig. 1. A modular and generalizable design for photoswitchable kinases.

(A) Photodissociable dimeric Dronpa (pdDronpa) variants were engineered from tetrameric DronpaN145. Residues 145 and 158 were further mutated to tune affinity. (B) Structural model of ps(ΔNT)MEK1 in the pre-illuminated state, showing the MEK1 core kinase domain with active site (asterisk) caged by pdDronpa1 domains attached at the NT and the GH loop (rendering based on PDB files 1S9J for MEK1 and 2Z6Y for Dronpa). Note ps(ΔNT)MEK1 contains constitutively activating mutations as well. (C) Light-dependent induction of ERK phosphorylation (pERK) by psMEK1 and psMEK1tight. (D) Structural alignment of MEK1 (PDB 1S9J) with MEK2 (PDB 1S9I). (E) Light-dependent induction of pERK by psMEK2. (F) Structural alignment of MEK1 (PDB 1S9J) with Raf1 (PDB 3MOV). (G) Light-dependent induction of pERK by psRaf1. Note psRaf1 contains a C-terminal CAAX motif for constitutive membrane localization. In (C,E,G), cells were illuminated by 20-mW/cm2 cyan light for 2 min. Protein was detected via an N-terminal HA tag, and lysate loading was monitored by blotting for GAPDH. Serum stimulations were for 5–10 min. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n = 3. (H) psMEK1 activation can be temporally and reversibly controlled. Upper panels, intrinsic pdDronpa fluorescence in psMEK1. Lower panels, mRuby2 fluorescence of the ERK KTR sensor. Cells were illuminated with 200-mW/cm2 cyan light for 1 min after the 0- and 60-min timepoints, and with 200-mW/cm2 violet light for 3 s after the 30-min timepoint. pdDronpa fluorescence was imaged immediately after each light stimulation. Scale bar, 20 μm. Chart, quantification of cytosolic/nuclear KTR fluorescence over time. Error bars represent s.e.m. of imaged cells.

We set out to create single-chain optically controllable MEK1 using pdDronpa1 domains. The Raf-MEK-ERK signaling pathway plays vital roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration (32), with cellular outcomes depending strongly on the dynamics of activation (33–35). While Raf1 and the upstream activator Sos can be optically regulated via light-induced membrane recruitment (25, 26), this is not suitable for controlling MEK, which is primarily localized to the cytosol regardless of pathway activity (36). To create a light-induced MEK, we first determined locations where insertion of pdDronpa domains could cage activity in the non-illuminated dimerized state. In addition to fusion at a terminus of the kinase, insertion of pdDronpa within the kinase domain should be possible, as the amino terminus (NT) and carboxyl terminus (CT) of pdDronpa are located near each other. We identified the GH loop in MEK1, located across the active site from the MEK1 NT (37), as a favorable insertion point for pdDronpa (Fig. 1B). We thus explored caging MEK1 activity by fusing one pdDronpa1 domain at the kinase domain NT and a second one in the GH loop.

We first verified that attachment of monomeric FP domains at these two locations did not abolish MEK1 activity. A fusion of a single monomeric Dronpa domain at the NT of a constitutively active and minimized MEK1 kinase domain (active(ΔNT)MEK1), comprising amino acids (aa) 61-393 with S218D and S222D phosphomimetic mutations but lacking the flexible N-terminal substrate-binding domain (Fig. S5A), drove phosphorylation of ERK independent of light, as expected (Fig. S5B). Constructs with monomeric Dronpa inserted at various GH loop positions from aa 298 to aa 305 were also fully active (Fig. S5C). Finally, active(ΔNT)MEK1 with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fused to the NT and monomeric Dronpa inserted at aa 304 produced levels of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) comparable to active(ΔNT)MEK1 alone (Fig. S5D), confirming that MEK1 retains activity with non-dimerizing FP domains fused at the NT and in the GH loop.

We next tested whether active(ΔNT)MEK1 bearing dimerizing domains at the NT and GH loop would be caged at baseline. Indeed, attachment of pdDronpa1 domains at the NT and at aa 304 (creating proto-photoswitchable(ΔNT)MEK1, or proto-ps(ΔNT)MEK1) completely caged MEK1 activity to levels comparable to catalytically inactive MEK1 (Fig. S5D). Other insertion points in the GH loop also allowed efficient caging (Fig. S5E). We then tested the ability of proto-ps(ΔNT)MEK1 to be regulated by light. lllumination of cells expressing proto-ps(ΔNT)MEK1 induced pERK (Fig. S5F). However, induced pERK levels were low compared to those produced by active(ΔNT)MEK1. Optical induction was enhanced by introducing a N145K mutation in the second pdDronpa1, creating ps(ΔNT)MEK1. However, ps(ΔNT)MEK1 after photoinduction was still less active on ERK than unfused active(ΔNT)MEK1.

In full-length MEK1, aa 1-60 contains a substrate docking site that enhances affinity for ERK 5- to 10-fold (38). Restoring this sequence to the NT of proto-ps(ΔNT)MEK1 increased basal activity (Fig. S5G). However, introducing V158I mutations into the pdDronpa1 domains to strengthen hydrophobic contacts at the dimeric interface, creating pdDronpa1.2 (Fig. S5H), reduced basal activity while maintaining robust light responsiveness (Fig. S5G). Maximal photoinduced pERK levels with this construct, designated photoswitchable MEK1 (psMEK1) were higher than with 20% serum stimulation (Fig. 1C). Basal ERK phosphorylation was further suppressed by reducing the length of the N-terminal linker, as expected for a steric caging mechanism, creating psMEK1tight (Fig. 1C). Topologically, psMEK1 and psMEK1tight can be considered full-length constitutively active MEK1 with insertions of pdDronpa1.2 before aas 61 and 305 (Fig. S6A,B).

We investigated whether our approach can be generalized to other serine/threonine kinases, which all share a similar three-dimensional structure (39). We first ported the psMEK1 design to the closely related MEK2 (85% identical in the kinase domain, Fig. 1D). Replacing the constitutively active MEK1 sequences in psMEK1 with homologous sequences from constitutively active MEK2 (Fig. S6C) produced a robust photoswitchable MEK2 (psMEK2) that mediated light-induced ERK phosphorylation to levels similar to serum stimulation without further optimization (Fig. 1E). The photoswitchable kinase design thus appears easily generalizable within the same kinase family. We next attempted to construct a photoswitchable variant of Raf1, the kinase immediately upstream of MEK1, which is only 22% identical in the kinase domain (Fig. 1F). Previous studies have found that membrane targeting is sufficient for Raf1 activation (40). To create photoswitchable Raf1 (psRaf1), we appended a CAAX signal to the C-terminus of the wild-type Raf1 kinase domain and attached pdDronpa1 and pdDronpa1 K145 at sites homologous to those in psMEK1 (Fig. S6D). Cyan-illuminated psRaf1 induced pERK to levels similar to serum stimulation, while basal activity was comparable to untransfected cells (Fig. 1G). Thus, the photoswitchable kinase design is generalizable to multiple kinases.

Optical control allows spatiotemporal precision in induction, but in the case of our photoswitchable kinases, the ability to restore pdDronpa dimerization with violet light may allow recaging and thereby precise termination of kinase activity as well. Using psMEK1 and a translocation reporter of ERK phosphorylation, ERK KTR-mRuby2 (41), we demonstrated that photoswitchable kinases enable dosable and spatiotemporal control of biochemical events (Supplementary Note, Fig. S7–S8). psMEK1 did not produce detectable pathway output when expressed at moderate levels without illumination (Supplementary Note, Fig. S8). We also found that psMEK1 effects could be rapidly reversed with violet light, enabling multiple rounds of kinase activation and inactivation (Fig. 1H). Finally, we tested if photoswitchable kinases induced similar effects as the native kinases, and found that Dronpa fusions did not affect kinase activation, kinetics, pathway dynamics, or substrate specificity (Supplementary Note, Fig. S9).

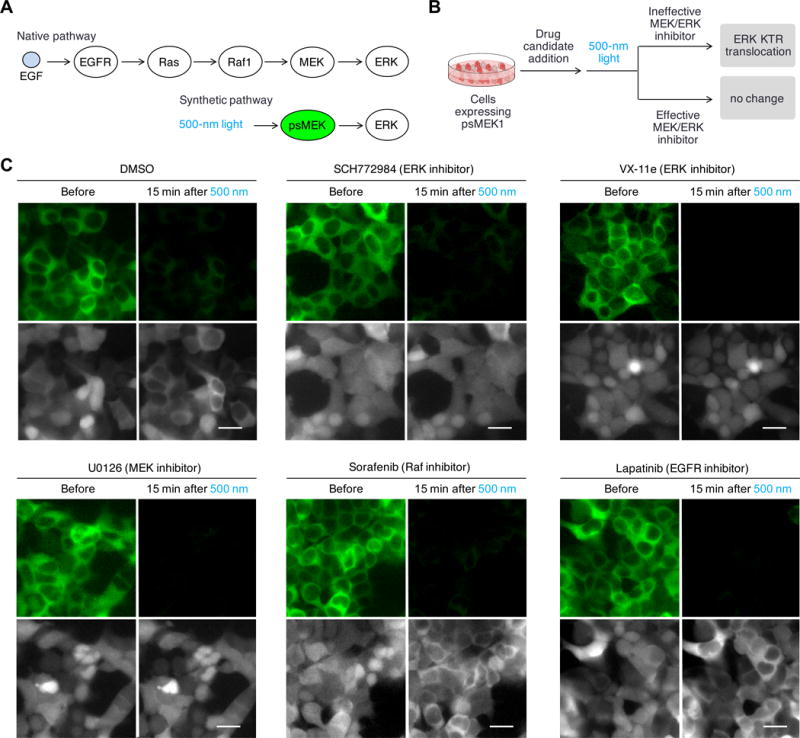

The ability to control kinase activity with light and the availability of optical reporters such as ERK KTR suggests an all-optical method for kinase inhibitor screening, which would have certain advantages. Photoinduction would be specific to the introduced photoswitchable kinase, whereas serum or growth factor stimulation would activate multiple pathways. By bypassing upstream steps (Fig. 2A), photoinduction enables screening for inhibitors specific for particular downstream steps. Furthermore, the timing of imaging can be optimized to identify inhibitors with immediate rather than delayed effects. We devised a screening procedure in which cells stably expressing psMEK1 and ERK KTR-mRuby2 were incubated with drug candidates and then stimulated by cyan light during timelapse microscopy of ERK KTR (Fig. 2B). Effective inhibitors were expected to block light-induced ERK KTR translocation. Testing the ERK inhibitors SCH772984 and VX-11e and the MEK inhibitor U0126, we found that all three inhibitors prevented light-induced KTR translocation as expected (Fig. 2C). Inhibitors against upstream proteins Raf1 and EGFR did not block the light-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2C), also as desired. These results demonstrated that all-optical kinase assays can allow the identification of inhibitors specifically against MEK or ERK, kinases which are of current clinical interest (42, 43). This concept should be adaptable to other kinases for which photoswitchable variants can be made.

Fig. 2. Cells expressing psMEK1 and ERK KTR sensor enables all-optical cell-based assay for MEK and ERK inhibitors.

(A) In native pathway, chemical ligands such as EGF activates receptor kinases EGFR, which then activates Ras. Activated Ras binds and activates Raf-1, which leads to MEK activation. In the synthetic pathway, psMEK1 is solely controlled by light and no longer respond to upstream activations. (B) Proposed all-optical cell-based assay for MEK and ERK inhibitors. Cells expressing psMEK1-P2A-ERK KTR-mRuby would be first incubated with drug candidates and then stimulated with light. The distribution of ERK KTR-mRuby2 would be monitored to determine whether light could induce ERK phosphorylation in the presence of the drug. (C) The assay allowed determination of inhibitors specifically targeting MEK and ERK. Upper panels, 1 min of cyan light stimulation at 200-mW/cm2 switched off pdDronpa fluorescence; lower panels, ERK KTR-mRuby2 translocation was monitored. We observed that cells incubated with ERK inhibitor SCH772984 and VX-11e, and MEK inhibitor U0126, did not show ERK KTR-mRuby2 translocation in response to psMEK1 activation, but cells incubated with DMSO or inhibitors against upstream MEK activators Raf1 or EGFR, Sorafenib and Lapatinib, showed ERK KTR. Scale bar, 20 μm.

We next used the photoswitchable kinases to investigate negative feedback in the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. We observed that illumination of psRaf1 induced pERK peaking at 2 min and then decaying (Fig. S10A). Seeking to understand the mechanism of this rapid downregulation, we first asked if downregulation occurred only at the level of ERK or upstream of it. The activation loop in psMEK1 contains phosphomimetic sites to render the kinase domain constitutively active, so psMEK1 cannot be downregulated by dephosphorylation. Thus, photoinduction of psMEK1 can specifically test for the presence of negative feedback directly on ERK. We found that increasing activation of psMEK1 resulted in increasing pERK in a nearly linear fashion (Fig. S10B), suggesting that downregulation of pERK following psRaf1 photoinduction occurred upstream of ERK, at the level of psRaf1 or endogenous MEK1/2.

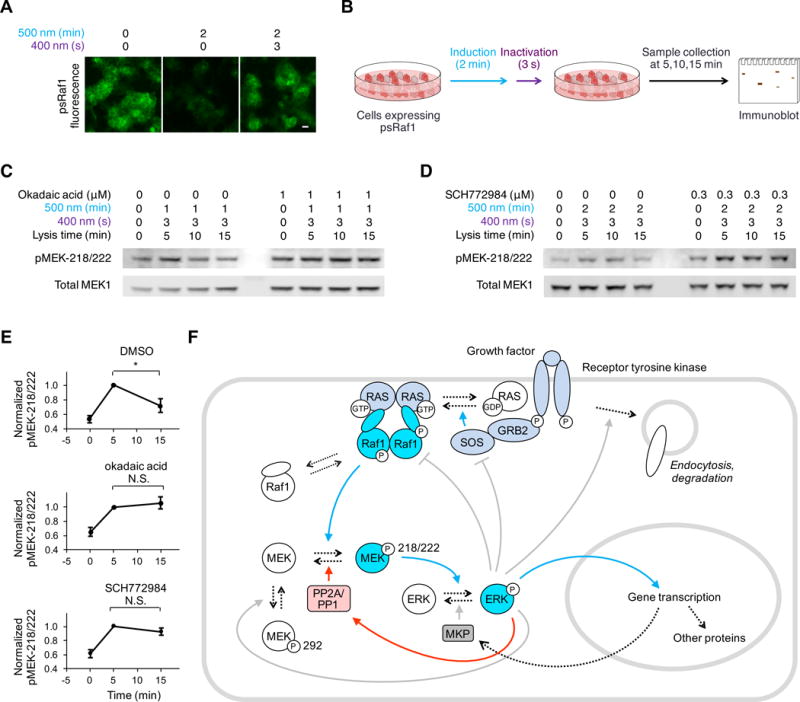

We asked if psRaf1 photoinduction causes biphasic activation and downregulation of endogenous MEK1/2. To separate Raf1 activity and downstream feedback events in time, we took advantage of the bidirectionally photoswitchable nature of psRaf1 to create a short pulse of Raf1 activity. We verified that psRaf1 fluorescence was effectively switched off by a 2-min pulse of 20-mW/cm2 500-nm light and fully recovered by 3 s of 10-mW/cm2 400-nm light (Fig. 3A). We performed a pulse of photoinduction of psRaf1 using these conditions, then collected samples over time to track the fate of MEK1/2 phosphorylated at activating sites 218 and 222 (pMEK-218/222) during the cyan light pulse (Fig. 3B). Indeed, pMEK-218/222 was downregulated at later times (Fig. 3C–E), confirming that psRaf1 photoinduction led to negative feedback on endogenous MEK1/2.

Fig. 3. Photoswitchable kinases allows fine dissection of Raf-MEK signaling and identification of a novel fast feedback mechanism.

(A) 2 min illumination by 20-mW/cm2 500-nm light effectively switched off pdDronpa fluorescence. 3 s of illumination by 10-mW/cm2 400-nm light fully recovered pdDronpa fluorescence. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Cells stably expressing psRaf1 were illuminated by 500-nm light for 1–2 minutes followed by illumination with 400-nm light. Cell are then collected at 5,10,15 min and immunoblotted. (C) MEK phosphorylation is downregulated over time, and downregulation requires PP2A/PP1. Lysis time means the time from the start of the stimulation to cell lysis. (D) MEK phosphorylation is downregulated over time, and downregulation requires ERK activity. Lanes 1–4, decreases of pMEK-218/222 occurred over time after transient activation of psRaf1 (by 1–2 min of 500-nm light followed by 3 s 400-nm light), demonstrating that dephosphorylation of pMEK-218/222 occurs. Right, downregulation of pMEK did not occur in cells incubated with ERK inhibitor SCH772984, indicating that ERK regulates the phosphatase activity. (E) Quantification of pMEK-218/222 over time in cells treated with DMSO, okadaic acid, or SCH772984. Error bars are standard error of the mean (n = 3). Unpaired two-sided t-tests were used for statistical analysis. (F) Simplified diagram of known positive (blue arrows) and negative (gray arrows) regulatory pathways mediating signaling from growth factor receptors to ERK. The new proposed pathway of ERK-induced dephosphorylation of pMEK218/222 is marked with red arrows. Dashed arrows indicate protein transitions, while solid arrows indicate regulatory effects.

As psRaf1 was recaged after the cyan pulse period, the pMEK-218/222 signal at all time points assayed was generated during the pulse. Thus the reduced levels of pMEK-218/222 at later time points could not have been due to downregulation of psRaf at these later times, but instead must have been due to a phosphatase acting on the pMEK-218/222 produced during the pulse. We considered if the responsible phosphatase was PP1 or PP2A, which has been suggested to dephosphorylate MEK1/2 (44). Indeed, the PP1/PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid blocked negative feedback on pMEK-218/222 following pulsed psRaf1 photoinduction (Fig. 3C,E). Finally, we asked if dephosphorylation was dependent on ERK activity. Indeed, downregulation of pMEK-218/222 was blocked by the ERK inhibitor SCH772984 (Fig. 3D,E). Taken together, these results indicate the existence a negative feedback pathway in which ERK induces PP1 or PP2A to dephosphorylate MEK1/2 at 218 and 222 (Fig. 3F), terminating further activation of ERK and subsequently allowing dephosphorylation of ERK by MKP to dominate.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to generate feedback inhibition in the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway, including endocytosis and degradation of tyrosine kinase receptors (2, 45), phosphorylation of regulatory sites (34, 42, 46), and transcriptional regulation of phosphatases (47). However, none of these reported mechanisms directly reverses the biochemical changes generated by pathway activation (Fig. 3F). And while PP1 or PP2A have been known to downregulate the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway (42), whether they are rapidly regulated by pathway activity was unknown. A major impediment to deciphering feedback inhibition was the inability of biochemical methods to create a short pulse of activity specific to the Raf-MEK-ERK cassette to observe time-courses of downregulation. Here, we used the bidirectional photoswitchability of psRaf1 to create a pulse of activity, which revealed that dephosphorylation of MEK at 218/222 by PP1 or PP2A is induced by ERK (Fig. 3F). Adding to recent work with heterodimeric optobiochemical systems (25, 26), these findings highlight how the ability of photoswitchable proteins to create pulses of activity can be useful for kinetic assessment of downstream events.

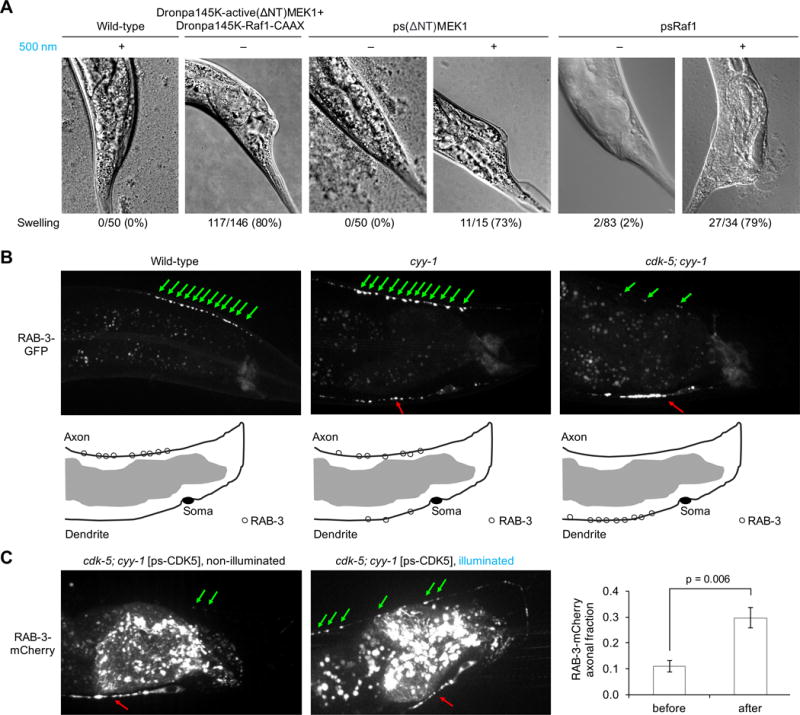

Finally, we determined whether psRaf1 and psMEK1 can induce physiological effects in a light-dependent manner in a living animal. In the roundworm C. elegans, the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is activated by bacterial rectal infection to induce a protective tail swelling response (48). We confirmed that expressing active(ΔNT)MEK1 and Raf1-CAAX constructs in hypodermis and gut cells induced tail swelling with 80% penetrance (Fig. 4A, Fig. S11). We then asked if ps(ΔNT)MEK1 or psRaf1 can induce these effects in a light-dependent manner. Worms expressing ps(ΔNT)MEK1 or psRaf1 showed no or very low rates of tail swelling in the dark (0 or 2% penetrance, respectively), suggesting that the activities of ps(ΔNT)MEK1 and psRaf1 were well caged in vivo. In contrast, after exposure to low-intensity (0.7-mW/cm2) cyan light for 24–48 h, worms expressing psMEK1or psRaf1 exhibited tail swelling with 73% (psMEK1) or 79% (psRaf1) penetrance (p < 0.0001 compared to non-illuminated penetrance by two-sided Fisher’s exact test). These results demonstrate that the psMEK1 and psRaf1 proteins enable optical control over the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway in a living animal.

Fig. 4. Optical control of kinase activity in living animals.

(A) Wild-type C. elegans worms showed no swollen tails even when grown in 500-nm light, while 80% of worms expressing DronpaK145-active(ΔNT)MEK1 and DronpaK145-Raf1-CAAX exhibited swollen tails in the dark (n = 146). 100% of worms expressing psMEK1 in the dark had normal tail shape (n = 50), while 73% of worms expressing psMEK1 in cyan light showed tail swelling (n = 15). Among worms expressing psRaf1, 98% had normal tail shape in the dark (n = 83), while 79% showed tail swelling in light (n = 34). (B) In wild-type worms, synaptic vesicles marked by RAB-3-GFP localize exclusively in the axon. In cyy-1 mutants, RAB-3-GFP is partly mislocalized to the dendrite. In cyy-1;cdk-5 double-mutant worms, nearly all RAB-3-GFP localized to the dendrite. Green and red arrows mark vesicles located in the axon and dendrite, respectively. (C) Light-dependent restoration of CDK5 function in cdk-5;cyy-1 worms. Nearly all RAB-3-mCherry in cyy-1;cdk-5 worms expressing psCDK-5 localized in the dendrite in the absence of light (n = 11), similar to cyy-1;cdk-5 worms. Cyan illumination restored axonal localization of some vesicles (n = 10), similar to the phenotype of cyy-1 worms. The light effect was statistically significant (p = 0.006, unpaired two-sided t-test). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Worms were exposed to 400-nm light at 0.7-mW/cm2 for 24–48 h before imaging.

To further demonstrate the generalizability of the photoswitchable kinase design and its ability to investigate protein in vivo, we created a photoswitchable cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (psCDK5) in the same manner as psMEK1 and psRaf1 (Fig. S6E). In multiple animal species, CDK5 regulates the differentiation and maintenance of neuronal structures (49). In worms, loss of CDK5 enhances the phenotype of cyclin Y deficiency, in which synaptic vesicles mislocalize to the dendrite of the DA9 neuron (50). Specifically, cyy-1;cdk-5 worms mislocalize nearly all vesicles to dendrites, whereas in cyy-1 worms, only a fraction of vesicles are mislocalized (Fig. 4B). We hypothesized that cyy-1;cdk-5 worms expressing psCDK5 would exhibit light-dependent restoration toward the cyy-1 phenotype, in which the majority of vesicles are situated correctly in axons. We found that nearly all vesicles in psCDK5-expressing cyy-1;cdk-5 worms distributed in the dendrite in the dark, as expected. After exposure of these worms to 24 h of cyan light (0.7-mW/cm2), significantly more vesicles appeared in axons (p = 0.006, two-sided t-test), resembling the phenotype of cyy-1 worms (Fig. 4C). These results show that a photoswitchable kinase can recapitulate wild-type kinase functionality in the photoinduced state.

In summary, engineered new pdDronpa domains and identifying favorable attachment points on kinase domains, we have created multiple single-chain photoswitchable kinases. Besides bidirectional photocontrol of activity, the autocatalytic and fluorescent chromophore of pdDronpa also allows independence from biochemical cofactor availability and enables self-reporting of the activation state. Only the testing of several linker lengths and pdDronpa affinity variants was required to create different light-regulated constructs. Our experience suggests a rational process for optimizing a photoswitchable variant for a given kinase of interest (Fig. S12). As all serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases have the same basic scaffold (39), our approach could potentially be applied to impart optical control to many kinases.

Our work also suggests that pdDronpa insertion may be a versatile method for optobiochemical control beyond kinases. Loops occur frequently near functional surfaces of proteins, as they serve to link secondary structural elements. We found that pdDronpa domains can be inserted into loops of a protein of interest while preserving the functions of both pdDronpa and the protein. Thus it may be possible to control accessibility of many protein surfaces in a light-dependent manner using pdDronpa.

Supplementary Material

One Sentence Summary.

Single-chain photoswitchable kinases based on engineered photodissociable proteins enable fine control of kinase activity in cells and animals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gulsen Colakoglu (Stanford) for assistance with worm experiments; Yuyong Tao and Liang Feng (Stanford) for assistance with crystallographic data collection and analysis; Xiang Liu (TJAB, China) and Tianmin Fu (Harvard) for assistance with protein structure refinement; John Philo (Alliance Protein Laboratories) for assistance with sedimentation equilibrium analysis; Li Tao and Gulsen Colakoglu (Stanford) for assistance with the worm experiments; Takamasa Kudo, Sergi Regot and Markus Covert (Stanford) for ERK KTR constructs; Kai Zhang and Bianxiao Cui (Stanford) for the Raf1 plasmid; Rose Tran, Xiaomin Bao, and Paul Khavari (Stanford) for the MEK1 plasmid, and Michael Davidson (National High Magnetic Field Laboratory) for the Neptune1-fascin plasmid. We also thank members of the Lin laboratory for valuable assistance with experiments and advice on the manuscript. This work was supported by a Stanford Graduate Fellowship and a HHMI International Graduate Student Fellowship (X.X.Z.), by the Stanford School of Engineering Undergraduate Visiting Researcher Program (L.Z.F.), and by NIH Pioneer Award 5DP1GM111003 (M.Z.L.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.X.Z. designed and characterized light-inducible kinases, generated protein crystals and solved X-ray structures, performed worm experiments, engineered pdDronpa1 variants, and co-wrote the manuscript. L.Z.F. designed and characterized pdDronpaV and pdDronpaM, and characterized light-inducible intersectin. P.L. performed worm transgenesis and imaging. K.S. provided advice and supervision on worm experiments. M.Z.L. conceived of experiments, provided advice, and co-wrote the manuscript. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Material

Materials and Methods

References (51–64)

References and Notes

- 1.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron JJ, Di Guglielmo GM, Dahan S, Dominguez M, Posner BI. Spatial and Temporal Regulation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Activation and Intracellular Signal Transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016 doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purvis JE, Lahav G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell. 2013;152:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu-Sato S, Huq E, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. A light-switchable gene promoter system. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1041–1044. doi: 10.1038/nbt734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazawa M, Sadaghiani AM, Hsueh B, Dolmetsch RE. Induction of protein-protein interactions in live cells using light. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:941–945. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy MJ, et al. Rapid blue-light-mediated induction of protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:973–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strickland D, et al. TULIPs: tunable, light-controlled interacting protein tags for cell biology. Nature methods. 2012;9:379–384. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lungu OI, et al. Designing photoswitchable peptides using the AsLOV2 domain. Chem Biol. 2012;19:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crefcoeur RP, Yin R, Ulm R, Halazonetis TD. Ultraviolet-B-mediated induction of protein-protein interactions in mammalian cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1779. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller K, et al. Multi-chromatic control of mammalian gene expression and signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano F, Suzuki H, Furuya A, Sato M. Engineered pairs of distinct photoswitches for optogenetic control of cellular proteins. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6256. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen D, Gibson ES, Kennedy MJ. A light-triggered protein secretion system. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:631–640. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, et al. Reversible protein inactivation by optogenetic trapping in cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11:633–636. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nihongaki Y, Kawano F, Nakajima T, Sato M. Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 for optogenetic genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:755–760. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Chen X, Yang Y. Spatiotemporal control of gene expression by a light-switchable transgene system. Nature Methods. 2012;9:266–269. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bugaj LJ, Choksi AT, Mesuda CK, Kane RS, Schaffer DV. Optogenetic protein clustering and signaling activation in mammalian cells. Nature methods. 2013;10:249–252. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motta-Mena LB, et al. An optogenetic gene expression system with rapid activation and deactivation kinetics. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:196–202. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dagliyan O, et al. Engineering extrinsic disorder to control protein activity in living cells. Science. 2016;354:1441–1444. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasser C, et al. Engineering of a red-light-activated human cAMP/cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8803–8808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321600111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, et al. Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science. 2008;322:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1159052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strickland D, Moffat K, Sosnick TR. Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wend S, et al. Optogenetic control of protein kinase activity in mammalian cells. ACS synthetic biology. 2013;3:280–285. doi: 10.1021/sb400090s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toettcher JE, Weiner OD, Lim WA. Using optogenetics to interrogate the dynamic control of signal transmission by the Ras/Erk module. Cell. 2013;155:1422–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang K, et al. Light-mediated kinetic control reveals the temporal effect of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in PC12 cell neurite outgrowth. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grusch M, et al. Spatio-temporally precise activation of engineered receptor tyrosine kinases by light. The EMBO journal. 2014;33:1713–1726. doi: 10.15252/embj.201387695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang KY, et al. Light-inducible receptor tyrosine kinases that regulate neurotrophin signalling. Nature communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim N, et al. Spatiotemporal control of fibroblast growth factor receptor signals by blue light. Chem Biol. 2014;21:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou XX, Chung HK, Lam AJ, Lin MZ. Optical control of protein activity by fluorescent protein domains. Science. 2012;338:810–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1226854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evers TH, van Dongen EM, Faesen AC, Meijer EW, Merkx M. Quantitative understanding of the energy transfer between fluorescent proteins connected via flexible peptide linkers. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13183–13192. doi: 10.1021/bi061288t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang F, et al. Signal transduction mediated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway from cytokine receptors to transcription factors: potential targeting for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia. 2003;17:1263–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albeck JG, Mills GB, Brugge JS. Frequency-modulated pulses of ERK activity transmit quantitative proliferation signals. Molecular cell. 2013;49:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin SY, et al. Positive-and negative-feedback regulations coordinate the dynamic behavior of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signal transduction pathway. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:425–435. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen-Saidon C, Cohen AA, Sigal A, Liron Y, Alon U. Dynamics and variability of ERK2 response to EGF in individual living cells. Molecular cell. 2009;36:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng CF, Guan KL. Cytoplasmic localization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase activator MEK. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:19947–19952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohren JF, et al. Structures of human MAP kinase kinase 1 (MEK1) and MEK2 describe novel noncompetitive kinase inhibition. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2004;11:1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/nsmb859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardwell AJ, Flatauer LJ, Matsukuma K, Thorner J, Bardwell L. A conserved docking site in MEKs mediates high-affinity binding to MAP kinases and cooperates with a scaffold protein to enhance signal transmission. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:10374–10386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010271200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endicott JA, Noble MEM, Johnson LN. The structural basis for control of eukaryotic protein kinases. Annual review of biochemistry. 2012;81:587–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052410-090317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu J, et al. Allosteric activation of functionally asymmetric RAF kinase dimers. Cell. 2013;154:1036–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regot S, Hughey JJ, Bajar BT, Carrasco S, Covert MW. High-sensitivity measurements of multiple kinase activities in live single cells. Cell. 2014;157:1724–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cseh B, Doma E, Baccarini M. “RAF” neighborhood: Protein-protein interaction in the Raf/Mek/Erk pathway. FEBS letters. 2014;588:2398–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samatar AA, Poulikakos PI. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2014;13:928–942. doi: 10.1038/nrd4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bae D, Ceryak S. Raf-independent, PP2A-dependent MEK activation in response to ERK silencing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goh LK, Sorkin A. Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a017459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catalanotti F, et al. A Mek1-Mek2 heterodimer determines the strength and duration of the Erk signal. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:294–303. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fritsche Guenther R, et al. Strong negative feedback from Erk to Raf confers robustness to MAPK signalling. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:489. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicholas HR, Hodgkin J. The ERK MAP kinase cascade mediates tail swelling and a protective response to rectal infection in C. elegans. Current biology. 2004;14:1256–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhavan R, Tsai LH. A decade of CDK5. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2001;2:749–759. doi: 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ou CY, et al. Two cyclin-dependent kinase pathways are essential for polarized trafficking of presynaptic components. Cell. 2010;141:846–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.