Abstract

Background & Aims

Focal zone 1 steatosis, although rare in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), does occur in children with NAFLD. We investigated whether focal zone 1 steatosis and focal zone 3 steatosis are distinct subphenotypes of pediatric NAFLD. We aimed to determine associations between the zonality of steatosis and demographic, clinical, and histologic features in children with NAFLD.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of baseline data from 813 children (age less than 18 years; mean age, 12.8±2.7 years). The subjects had biopsy-proven NAFLD and were enrolled in the NASH Clinical Research Network. Liver histology was reviewed using the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network scoring system.

Results

Zone 1 steatosis was present in 18% of children with NAFLD (n=146) and zone 3 steatosis was present in 32% (n=244). Children with zone 1 steatosis were significantly younger (10 vs 14 years; P<.001) and a significantly higher proportion had any fibrosis (81% vs 51%; P<.001) or advanced fibrosis (13% vs 5%; P<.001) compared to children with zone 3 steatosis. In contrast, children with zone 3 steatosis were significantly more likely to have steatohepatitis (30% vs 6% in children with zone 1 steatosis; P<.001).

Conclusion

Children with zone 1 or zone 3 distribution of steatosis have an important sub-phenotype of pediatric NAFLD. Children with zone 1 steatosis are more likely to have advanced fibrosis and children with zone 3 steatosis are more likely to have steatohepatitis. In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of pediatric NAFLD, studies of pathophysiology, natural history, and response to treatment should account for the zonality of steatosis.

Keywords: NASH, pediatric, disease progression, obesity

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in children, with an estimated prevalence of 9.6% in the United States 1. NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of severity ranging from isolated steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with or without fibrosis. The histologic triad of classically described NASH in adults includes fat accumulation in hepatocytes, inflammation, and liver injury as manifest by hepatocyte ballooning 2. These same features can be identified in the livers of children with NAFLD, but there are distinct differences in the microscopic appearance in many pediatric cases. Specifically, children with fatty liver disease may have more steatosis, fewer ballooned hepatocytes and more portal-based inflammation and/or fibrosis 3.

Studies of steatosis in the context of NASH to date have focused largely on the amount of steatosis. For example, in a study in adults with NAFLD from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN), Neuschwander-Tetri et al found that those with moderate and severe steatosis were more likely to have NASH than those with only mild steatosis 4. In addition, in a study of children from the NASH CRN, children with hypertension tended to have more steatosis compared to those who were normotensive 5. Another study of adults with NAFLD showed that those with type 2 diabetes had more severe steatosis on histology compared to those without diabetes 6.

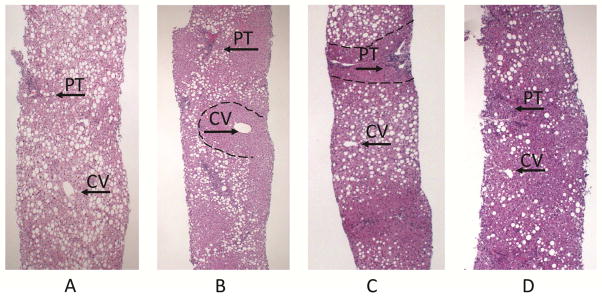

In addition to the percentage of hepatocytes with steatosis, steatosis can be categorized based on the hepatic zones in which fat droplets are present. Fat accumulation in hepatocytes may be microscopically subdivided in four distributions, regardless of amount: panacinar (even distribution), zone 1 (periportal), zone 3 (centrilobular or pericentral), and azonal (uneven distribution) (see figure 1). Previous research has shown that in adults with NAFLD, inflammation and fibrosis tend to be in zone 3 and not in zone 1. This is in contrast to children, in which inflammation and fibrosis are often present in zone 1, but can be seen in zone 3. Much less is known about the localization of steatosis in NAFLD than the localization of inflammation or fibrosis. Previous studies have shown about 10 percent of children have accentuation of steatosis in periportal, or zone 1, hepatocytes 3,7,8, whereas, zone 1 steatosis is uncommon in adults with NAFLD 8,9. Thus, clinical correlates of zone 1 versus zone 3 steatosis are relatively unexplored, and in order to do so would require a large population of children with biopsy-proven NAFLD. The NIH NASH CRN provides such a cohort as biopsy evaluation includes localization as well as amount of steatosis, and we therefore performed a multi-center, cross-sectional cohort study from this cohort with the aim of determining associations between zone 1 and zone 3 localizations of steatosis and demographic, clinical, and other histologic features in children with NAFLD. In addition to the percentage of hepatocytes with steatosis, steatosis can be categorized based on the hepatic zones in which fat droplets are present. Fat can accumulate in hepatocytes in four distributions: panacinar, zone 1 (periportal), zone 3 (centrilobular or pericentral), and azonal (see figure 1). Previous research has shown that in adults with NAFLD, inflammation and fibrosis tend to be in zone 3 and not in zone 1. This is in contrast to children, in which inflammation and fibrosis are often present in zone 1, but can be seen in zone 3. Much less is known about the localization of steatosis in NAFLD than the localization of inflammation or fibrosis. Previous studies have shown about 10 percent of children have accentuation of steatosis in periportal, or zone 1, hepatocytes 3,7,8, whereas, zone 1 steatosis is uncommon in adults with NAFLD 8,9. Thus, clinical correlates of zone 1 versus zone 3 steatosis are relatively unexplored, and in order to do so would require a large population of children with biopsy-proven NAFLD. The NIH NASH CRN provides such a cohort, and we therefore performed a multi-center, cross-sectional cohort study with the aim of determining associations between zone 1 and zone 3 localization of steatosis and demographic, clinical, and other histologic features in children with NAFLD.

Figure 1.

METHODS

Study Population

We included children < 18 years of age with NAFLD enrolled in the NASH CRN who were participants in one of the following studies: the longitudinal cohort studies Database and Database 2 (NCT01061684) or the randomized controlled trials Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children (TONIC) (NCT00063635) or Cysteamine Bitartrate Delayed-Release for the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children (CyNCh) (NCT01529268). The diagnosis of NAFLD was based on ≥5% of hepatocytes containing macrovesicular fat and exclusion of other causes of chronic liver disease based on clinical history, laboratory studies, and histology8. The institutional review board at each participating center approved these studies. Written consent was obtained from each participant’s parent or guardian, and written assent was obtained from each participant age 8 and older.

History and Physical Examination

Demographic data and clinical history were obtained via a structured interview developed by the NASH CRN. Weight and height were measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) per height (m) squared. BMI Z-score was calculated to account for age and sex and based on Center for Disease Control and Prevention reference standards.

Laboratory Studies

Participants fasted for 12 hours prior to collection of blood via venipuncture. Laboratory assays included: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, hemoglobin A1C, serum glucose, and serum insulin.

Liver Histology

The Pathology Committee of the NASH CRN reviewed H&E and trichrome stained slides in consensus conference according to the NASH CRN scoring system8. The pathologists were unaware of the clinical study, age, gender or other clinical features of the children at the time of review, including whether the biopsy was from a child or adult. Biopsies were given a score for degree of steatosis based on the following: grade 0 (none to <5%), grade 1 (5% to 33%), grade 2 (34% to 66%), and grade 3 (>66%). Lobular inflammation was categorized based on the assessment of all inflammatory foci: no foci, <2 foci per 200x field, 2–4 foci per 200x field, and >4 foci per 200x. Portal inflammation was categorized into three groups: none, mild, and more than mild. Ballooning was categorized into three groups: none, few, and many. Fibrosis was staged based on the following: stage 0 (no fibrosis), stage 1a (mild zone 3 perisinusoidal requiring trichrome stain), stage 1b (moderate zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis not requiring trichrome stain), stage 1c (portal/periportal fibrosis only), stage 2 (zone 3 perisinusoidal and periportal), stage 3 (bridging fibrosis), and stage 4 (cirrhosis). An overall diagnosis was made based on the composite features of the biopsy, but without regard to NAFLD Activity Score, according to the following categories: NAFLD not NASH, borderline zone 1 NASH, borderline zone 3 NASH, and definite NASH. Location of steatosis was noted as follows: zone 1 (periportal), zone 3 (perivenular), panacinar and azonal. Azonal (irregular) distribution of fat droplets was assigned to cases in two circumstances: 1) when clear zone 1, zone 3, or uniform panacinar patterns of steatosis were not apparent or 2) when cirrhosis or bridging fibrosis were present, as vascular landmarks are lost. Panacinar steatosis was recorded when there was an even distribution, regardless of amount, throughout the lobule and with no predilection for, or sparing of zones. The NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) was subsequently calculated from the scores assigned for steatosis amount, lobular inflammation and ballooning, as described 8.

Data Analysis

For this analysis, only cases with pure zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis were compared. The demographic, clinical, and histopathological characteristics of all children included in this study were reported using standard descriptive statistics. Children were divided into two groups for analysis: those with zone 1 steatosis and those with zone 3 steatosis. For continuous variables, sample mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval were calculated. Wilcoxon Rank test and two-sample t-test were used to compare demographic and laboratory continuous parameters among the two groups. For categorical variables, frequency and percentages were computed. Chi-square test was used to compare differences between the groups for binary categorical variables. Mantel-Haenszel Chi-Square Test was used to compare differences between the groups for ordinal categorical variables. Demographic factors influencing the presence of zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis were identified using multinomial logistic regression models, with presence of Zone 1 and Zone 3 as primary outcomes and candidate factors: age, sex, ethnicity, and BMI Z-score. Goodness of fit of the first logistic regression model (zone 1 vs other distributions) was assessed using a Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square test with p>0.05 indicating adequate fit. The likelihood ratio test, Score test, and Wald test assessed the fit of the model compared to an empty model. Parallel analysis was done with the second logistic regression model (zone 3 vs other distributions). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.2.3.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 813 children enrolled in the NASH CRN. Thirty-seven children were excluded because their liver biopsy results were not consistent with NAFLD. In the remaining 776 children, the zonality of steatosis in the liver biopsies was distributed as follows: zone 1=146 (19%), zone 3=244 (31%), azonal=59 (8%), panacinar=327 (42%). The remainder of data pertain to zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis cohorts; data for the panacinar and azonal cohorts are available in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

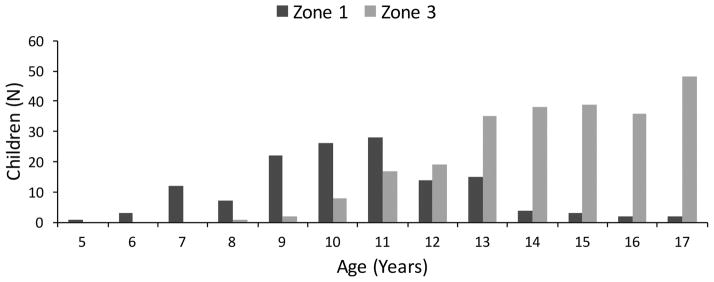

Demographic and Clinical Differences between Zone 1 and Zone 3 Steatosis Cohorts

Demographic and clinical parameters are shown in Table 1 for the 390 children with zone 1 or zone 3 steatosis. As shown in Figure 2, children with zone 1 steatosis were younger than children with zone 3 steatosis (mean age 10.8 (SD 2.1) vs 14.7 (SD 2.1) years, p<0.001). Children with zone 1 steatosis were more likely to be Hispanic (75% vs 58%, p=0.001) than those with zone 3 steatosis. Children with zone 1 steatosis had higher fasting triglyceride levels (164 vs 125 mg/dL, p<0.001) and lower fasting insulin (25 vs 39 μU/mL, p<0.001) than those with zone 3 steatosis. There was no significant difference in sex between children with zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis. Height, weight and BMI were all significantly different between zonality group, but BMI Z-score was not. Children with zone 3 steatosis had higher waist circumference (109.5 vs 96.4 cm, p <0.001), systolic blood pressure (125 vs 115 mmHg, P<0.001), and diastolic blood pressure (70 vs 65 mmHg, p<0.001) than those with zone 1 steatosis. There were no significant differences in ALT or GGT between groups, but there was a small but significant difference in AST, with those in Zone 1 steatosis group having higher AST (56 vs 52 U/L, p=0.017).

Table 1.

Demographic, Anthropometric, and Laboratory Values for Children with Zone 1 and Zone 3 Steatosis

| Characteristics | Total | Zone 1 | Zone 3 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or mean (SD) | N=390 | N=146 | N=244 | |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 13.3 (2.9) | 10.8 (2.1) | 14.7 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 274 (70.2) | 111 (76.0) | 163 (66.8) | 0.070 |

| Female | 116 (29.8) | 35 (24.1) | 81 (33.2) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 248 (63.9) | 108 (75.0) | 140 (57.6) | 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic | 140 (36.0) | 37 (25.0) | 103 (42.4) | |

| Anthropometric | ||||

| Height (cm) | 160.9 (14.4) | 149.9 (12.9) | 167.6 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 86.5 (26.5) | 67.9 (20.1) | 97.7 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.7 (6.6) | 29.6 (5.5) | 34.5 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI Z-score | 2.25 (0.42) | 2.22 (0.41) | 2.26 (0.43) | 0.434 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 104.6 (15.6) | 96.4 (13.9) | 109.5 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 122 (14) | 117 (12) | 125 (14) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 68 (10) | 65 (9) | 70 (10) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Values | ||||

| AST (U/L) | 53 (37) | 56 (34) | 52 (38) | 0.017 |

| ALT (U/L) | 86 (64) | 89 (67) | 85 (62) | 0.582 |

| GGT (U/L) | 41 (30) | 37 (24) | 43 (33) | 0.123 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 150 (89) | 125 (64) | 164 (99) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 100 (30) | 99 (26) | 101 (31) | 0.968 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 39 (9) | 40 (10) | 39 (9) | 0.064 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 168 (37) | 165 (30) | 170 (40) | 0.233 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87 (14) | 86 (9) | 88 (16) | 0.975 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 34 (31) | 25 (19) | 39 (36) | <0.001 |

Demographic and anthropometric continuous parameters using T-test, category parameter using Chi-square test. Laboratory continuous parameters using Wilcoxon Rank test.

Figure 2.

Histological Differences between Zone 1 and Zone 3 Steatosis

As shown in Table 2, there were distinct histological differences between the zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis groups, although the grades of steatosis did not differ for children with zone 1 or zone 3 steatosis. Biopsies with zone 3 steatosis had more ballooning compared to those with zone 1 steatosis (48% vs 29%, p<0.001), higher NAS score (4.1 vs 3.7, p=0.014), and a greater frequency of a diagnosis of definite NASH than biopsies with zone 1 steatosis (30% vs 6%, p<0.001). Biopsies with zone 1 steatosis had more portal inflammation than those with zone 3 steatosis (97% vs 75%, p<0.001). In univariate analysis, biopsies with zone 1 steatosis compared to biopsies with zone 3 steatosis had more fibrosis of any grade (80% vs 51%) and more advanced fibrosis (13% vs 5%) (p<0.001). In a multivariate logistic regression model, after controlling for age, sex, and BMI Z-score, children with zone 1 steatosis had 2.34 times the odds of having advanced fibrosis than children with zone 3 steatosis (95 CI 1.03-5.52).

Table 2.

Histological Characteristics for Children with Zone 1 and Zone 3 Steatosis

| Liver Histology | Total | Zone 1 | Zone 3 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N=390 | N=146 | N=244 | |

|

| ||||

| Steatosis | ||||

| 5–33% | 127 (32.6) | 50 (34.5) | 77 (31.6) | 0.844 |

| 34–66% | 150 (38.5) | 54 (36.9) | 96 (39.3) | |

| ≥66% | 113 (29.0) | 42 (28.8) | 71 (29.1) | |

| Portal Inflammation | ||||

| None | 45 (11.5) | 5 (3.4) | 40 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 285 (73.1) | 105 (71.9) | 180 (73.8) | |

| More than mild | 60 (15.4) | 36 (24.7) | 24 (9.8) | |

| Lobular inflammation | ||||

| <2 under 20x | 226 (57.9) | 81 (55.5) | 145 (59.4) | 0.444 |

| 2–4 under 20x | 139 (35.6) | 57 (39.0) | 82 (33.6) | |

| >4 under 20x | 24 (6.2) | 7 (4.8) | 17 (7.0) | |

| Ballooning | ||||

| None | 233 (59.7) | 104 (71.2) | 129 (52.9) | <0.001 |

| Few | 106 (27.2) | 36 (24.6) | 70 (28.7) | |

| Many | 51 (13.1) | 6 (4.1) | 45 (18.4) | |

| Fibrosis | ||||

| None | 147 (37.8) | 27 (18.6) | 120 (49.1) | <0.001 |

| Mild, Zone 3 perisinusoidal | 32 (8.2) | 2 (1.4) | 30 (12.3) | |

| Moderate, Zone 3 perisinusoidal | 22 (5.7) | 1 (0.7) | 21 (8.6) | |

| Portal/periportal only | 115 (29.6) | 91 (62.8) | 24 (9.8) | |

| Zone 3 and periportal | 43 (11.1) | 5 (3.5) | 38 (15.6) | |

| Bridging Fibrosis | 30 (7.7) | 19 (13.1) | 11 (4.5) | |

| NAS Score | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0.014 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| NAFLD, not NASH | 121 (31.0) | 21 (14.4) | 100 (40.9) | <0.001 |

| Borderline NASH: Zone 3 pattern | 61 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 61 (25.0) | |

| Borderline NASH: Zone 1 pattern | 125 (32.1) | 116 (79.5) | 9 (3.7) | |

| Definite NASH | 83 (21.3) | 9 (6.2) | 74 (30.3) | |

All parameters using Mantel-Haenszel Chi-Square Test

Logistic Regression Model for Zone 1 and Zone 3 Steatosis

Among all children with NAFLD, the only independent risk factor identified for having zone 1 steatosis was age. Specifically, children < 13 years had 6.3 (95 CI 3.9-10.4) times the odds of having zone 1 steatosis compared to children ≥ 13 years. In contrast, both age and sex were significant independent risk factors for having zone 3 steatosis. Thus, children with NAFLD who were ≥ 13 years had 9.0 (95 CI 6.3-13.2) times the odds of having zone 3 steatosis compared to children less than 13 years. In addition, girls with NAFLD had 1.6 (95 CI 1.1-2.3) times the odds of having zone 3 steatosis compared to boys with NAFLD. Ethnicity and BMI Z-score did not improve the fit of the model for either zone 1 or one 3 steatosis.

Subanalysis of Zone 3 Steatosis with Either Zone 1 or Zone 3 Fibrosis

Within the defined patterns of zonality of steatosis, there was a noted distribution of fibrosis, central/perisinusoidal and portal. As shown in Table 2, 94 (64%) biopsies with zone 1 steatosis had fibrosis that co-localized with the steatosis, with only 3 (3%) in this group having central/perisinusoidal fibrosis. Thus, due to the small number, this was not analyzed further.

In contrast, for those with zone 3 steatosis, 75 (31%) had fibrosis that was zonally restricted, and 24 (32%) of these had a portal fibrosis pattern. Therefore, we further analyzed differences of fibrosis patterns among children with biopsies showing zone 3 steatosis. As shown in Table 3, children with zone 3 steatosis and portal fibrosis were younger than those who had zone 3 steatosis with central fibrosis (14.1 vs 15.7 years, p=0.0142). In addition, there was a significant difference in ALT, with the central fibrosis group having higher mean ALT than the portal fibrosis group (97 U/L vs 56 U/L, p=0.0003). As expected, the portal fibrosis group had significantly more portal inflammation than the central fibrosis group (92% vs 78%, p=0.0112). There were also more children in the central fibrosis group with a diagnosis of definite NASH (55% vs 8%) and borderline zone 3 NASH (43% vs 12.5%) than the portal fibrosis group. There were more children in the portal fibrosis group that had borderline zone 1 NASH (17% vs 0%) (p<0.0001). There were no significant differences in sex, ethnicity, BMI Z-score, or steatosis grade between central and portal fibrosis groups.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Children with Zone 3 Steatosis and Mild Central or Portal Fibrosis

| Characteristics | Total | Central | Portal | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or mean (SD) | N=75 | N=51 | N=24 | |

|

| ||||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years) | 15.2 (2.2) | 15.7 (1.8) | 14.2 (2.7) | 0.0142 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 50 (66.7) | 36 (70.6) | 14 (58.3) | 0.2936 |

| Female | 25 (33.3) | 15 (29.4) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 36 (48.6) | 23 (46.0) | 13 (54.2) | 0.5106 |

| Non-Hispanic | 38 (51.4) | 27 (54.0) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Anthropometric | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.1 (0.7) | 35.0 (0.9) | 35.4 (1.4) | 0.8395 |

| BMI Z-score | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.25 (0.4) | 2.38 (0.4) | 0.2238 |

| Laboratory Values | ||||

| AST (U/L) | 52 (45) | 60 (52) | 35 (13) | <0.0001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 84 (56) | 97 (60) | 56 (32) | 0.0003 |

| GGT (U/L) | 44 (26) | 44 (28) | 42 (20) | 0.8602 |

| Liver Histology | ||||

| Steatosis | ||||

| 5–33% | 20 (26.7) | 10 (19.6) | 10 (41.7) | 0.0778 |

| 34–66% | 34 (45.3) | 25 (49.0) | 9 (37.5) | |

| >67% | 21 (28.0) | 16 (31.4) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Portal Inflammation | ||||

| None | 13 (17.3) | 11 (21.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.0112 |

| Mild | 56 (74.7) | 39 (76.5) | 17 (70.8) | |

| More than mild | 6 (8.0) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (20.9) | |

| Lobular Inflammation | ||||

| <2 under 20x | 42 (56.0) | 26 (50.9) | 16 (66.7) | 0.1712 |

| 2–4 under 20x | 29 (38.7) | 21 (41.2) | 8 (33.3) | |

| >4 under 20x | 4 (5.3) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ballooning | ||||

| None | 35 (46.7) | 19 (37.2) | 16 (66.7) | 0.0020 |

| Few | 22 (29.3) | 14 (27.4) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Many | 18 (24.0) | 18 (35.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| NAFLD, not NASH | 16 (21.3) | 1 (1.9) | 15 (62.5) | <0.0001 |

| Borderline NASH: Zone 3 Pattern | 25 (33.3) | 22 (43.1) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Borderline NASH: Zone 1 Pattern | 4 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Definite NASH | 30 (40.0) | 28 (54.9) | 2 (8.3) | |

Demographic and anthropometric continuous parameters using T-test, category parameter using Chi-square test. Laboratory continuous parameters using Wilcoxon Rank test.

DISCUSSION

We studied the zonal distribution of hepatic steatosis in a large cohort study of children with NAFLD from pediatric centers across the United States. Steatosis was confined to zone 1 or zone 3 in approximately half of biopsies with NAFLD. Age and sex were the major demographic characteristics that were associated with the zonal location of steatosis. Children with zone 1 steatosis were younger and more likely to be boys by logistic regression. Other associations with zone 1 steatosis were Hispanic ethnicity, higher AST and triglyceride levels, and lower insulin levels. Finally, biopsies with zone 1 steatosis were more likely to have fibrosis. In contrast, biopsies from children with zone 3 steatosis more frequently showed ballooning and were more likely to be diagnosed as definite NASH.

This cross-sectional study affirms the importance of steatosis zonality in the characterization of pediatric NAFLD. To distinguish classically described steatohepatitis 10,11 from a newly recognized pediatric zone 1 pattern, Schwimmer et al characterized Zone 3 predominant disease as “Type 1 NASH” and the Zone 1 predominant pattern as Type 2 NASH 3. In the current study, those children whose biopsies had zone 3 steatosis were similar to children with Type 1 NASH, namely older and less likely to be boys, while those with zone 1 steatosis were similar to the children categorized as Type 2 NASH, namely younger and with greater male predominance. These differences in zonality may have clinical implications, associated with alterations in insulin levels and triglyceride concentrations, and also possibly advanced fibrosis that can ultimately result in worsening liver function.

The hedgehog and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways may explain localization of steatosis to Zone 1 and Zone 3. The hedgehog pathway has higher activity in young children and lower activity in adulthood and has high activity in the portal/periportal region 12–14. This pathway is implicated in the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis in both animals and humans 14. This is in contrast to the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway, which becomes more active with age, very low in early development and more active in adulthood 15. This pathway has the highest canonical activity around the terminal hepatic venules and governs pathways involving glutamine synthesis, drug metabolism, bile acid, and heme synthesis 16. In addition, it is involved in hepatic development, regeneration, and response to oxidative stress. In murine models, pericentral steatosis with periportal sparing was found in beta-catenin transgenic mice given a high-fat diet, while beta-catenin knockout mice had periportal steatosis with perivenous sparing 17,18. The presence of zone 1 steatosis in younger patients could relate to immature or absent beta catenin pathway activity, while hedgehog pathway activity may be a potential clue why fibrosis was more common among children with zone 1 steatosis. These pathways may be potential targets of therapy.

In our study, children with zone 3 steatosis were older and had higher circulating insulin levels compared to those with zone 1 steatosis. Increased fasting insulin levels are often seen with metabolic syndrome. In the setting of metabolic syndrome, hepatocytes in zone 3 increasingly engage in glycolysis and de novo lipogenesis (DNL) resulting in a higher presence of zone 3 steatosis given that the activity of specific enzymes involved in DNL, such as ATP citrate lyase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and fatty acid synthase, are higher in zone 3 hepatocytes 19,20. There is also higher expression of triacylglycerol synthetic enzyme, triacylglycerol hydrolase, in zone 3 hepatocytes 21,22. We therefore speculate that these findings may indicate that the zone 3 steatosis pattern may be consistent with higher zone 3 DNL and lower VLDL export.

Importantly, localization of the fat droplets in the liver requires histology. Although AST levels were statistically different between children with Zone 1 or Zone 3 steatosis, the difference observed was not sufficient to allow stratification of steatosis by zone. There were statistically significant differences with waist circumference and blood pressure as well, though both of these are intimately related to age; older children will have higher waist circumferences and blood pressures. Also of note, there was no relationship between the severity of steatosis and the zonality of fat, making current imaging modalities unhelpful for this characterization. Clinically, there may be a reluctance to perform biopsies on children suspected to have NAFLD, though liver biopsies are safe and can help in the diagnosis of NASH and other causes of hepatitis with hepatic steatosis23. In post-hoc analysis of a recent study by the NASH CRN, there was significant histologic improvement in children with Borderline Zone 1 NASH compared to placebo. This is in contrast to those with other types of NASH, showing that there may be a difference in response to treatment based on zonation24. Hence, there are potential implications for the utility of biopsies for individual patients.

The characterization of subphenotypes of NAFLD based on zonality of steatosis is strengthened by the use of the NASH CRN, the largest prospective cohort of children with NAFLD in the U.S. The diagnosis of NAFLD subtype and specification of steatosis zonality were done in a standardized fashion blinded to submitting center or patient age, along with all features of biopsy analysis by the Pathology Committee. Although the method of analysis utilized does not result in a final score that highlights zonality, there are two features of the NASH CRN pathology method that can be suggestive of a pediatric pattern of NAFLD: the portal-based pattern of fibrosis (1c), and the diagnostic subtype, borderline zone 1. In this study, a subset of children had steatosis and fibrosis in different zones. It remains unclear how zonation of steatosis, along with inflammation and the development of fibrosis, change over time due to the cross-sectional nature of this study. Longitudinal studies are important to address questions regarding the development as well as the stability or instability of steatosis localization.

Conclusion

Zone 1 and zone 3 steatosis are two distinct subphenotypes of pediatric NAFLD that may be informative of risk differences in the progression of NAFLD, namely in terms of advanced fibrosis and steatohepatitis, respectively. Further work is needed to analyze the natural history and long-term outcomes associated with these steatosis zonality patterns as children grow and develop. A better understanding of the pathophysiologic differences between these steatosis zonality patterns may provide opportunities for targeted personalized therapies for children with NAFLD in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713). Additional support is received from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grants UL1TR000077, UL1TR000150, UL1TR000424, UL1TR000006, UL1TR000448, UL1TR000040, UL1TR000100, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000423, UL1TR000454).

Members of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network Pediatric Clinical Centers

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Stephanie H. Abrams, MD, MS (2007–2013); Sarah Barlow, MD; Ryan Himes, MD; Rajesh Krisnamurthy, MD; Leanel Maldonado, RN (2007–2012); Rory Mahabir, BS

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH: April Carr, BS, CCRP; Kimberlee Bernstein, BS, CCRP; Kristin Bramlage, MD; Kim Cecil, PhD; Stephanie DeVore, MSPH (2009–2011); Rohit Kohli, MD; Kathleen Lake, MSW (2009–2012); Daniel Podberesky, MD (2009–2014); Alex Towbin, MD; Stavra Xanthakos, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: Gerald Behr, MD; Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD; Jay H. Lefkowitch, MD; Ali Mencin, MD; Elena Reynoso, MD

Emory University, Atlanta, GA: Adina Alazraki, MD; Rebecca Cleeton, MPH, CCRP; Maria Cordero; Albert Hernandez; Saul Karpen, MD, PhD; Jessica Cruz Munos (2013–2015); Nicholas Raviele (2012–2014); Miriam Vos, MD, MSPH, FAHA

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN: Molly Bozic, MD; Oscar W. Cummings, MD; Ann Klipsch, RN; Jean P. Molleston, MD; Emily Ragozzino; Kumar Sandrasegaran, MD; Girish Subbarao, MD; Laura Walker, RN

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD: Kimberly Kafka, RN; Ann Scheimann, MD

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine/Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Joy Ito, RN; Mark H. Fishbein, MD; Saeed Mohammad, MD; Cynthia Rigsby, MD; Lisa Sharda, RD; Peter F. Whitington, MD

Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO: Sarah Barlow, MD (2002–2007); Theresa Cattoor, RN; Jose Derdoy, MD (2007–2011); Janet Freebersyser, RN; Ajay Jain MD; Debra King, RN (2004–2015); Jinping Lai, MD; Pat Osmack; Joan Siegner, RN (2004–2015); Susan Stewart, RN (2004–2015); Susan Torretta; Kristina Wriston, RN (2015)

University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY: Susan S. Baker, MD, PhD; Diana Lopez-Graham; Sonja Williams; Lixin Zhu, PhD

University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Jonathan Africa, MD; Hannah Awai, MD; Cynthia Behling, MD, PhD; Craig Bross; Jennifer Collins; Janis Durelle; Kathryn Harlow, MD; Michael Middleton, MD, PhD; Kimberly Newton, MD; Melissa Paiz; Jeffrey B. Schwimmer, MD; Claude Sirlin, MD; Patricia Ugalde-Nicalo, MD; Mariana Dominguez Villarreal

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Bradley Aouizerat, PhD; Jesse Courtier, MD; Linda D. Ferrell, MD; Natasha Feier, MS; Ryan Gill, MD, PhD; Camille Langlois, MS; Emily Rothbaum Perito, MD; Philip Rosenthal, MD; Patrika Tsai, MD

University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA: Kara Cooper; Simon Horslen, MB, ChB; Evelyn Hsu, MD; Karen Murray, MD; Randolph Otto, MD; Matthew Yeh, MD, PhD; Melissa Young

Washington University, St. Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD (2002–2015); Kathryn Fowler, MD (2012–2015)

Resource Centers

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD: Sherry Brown, MS; Edward C. Doo, MD; Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD; Patricia R. Robuck, PhD, MPH (2002–2011); Averell Sherker, MD; Rebecca Torrance, RN, MS

Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health (Data Coordinating Center), Baltimore, MD: Patricia Belt, BS; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; Michele Donithan, MHS; Erin Hallinan, MHS; Milana Isaacson, BS; Kevin P. May, MS; Laura

Miriel, BS; Alice Sternberg, ScM; James Tonascia, PhD; Mark Van Natta, MHS; Laura Wilson, ScM; Katherine Yates, ScM

List of Abbreviations

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- NASH CRN

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network

- TONIC

Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children

- CyNCh

Cysteamine Bitartrate Delayed-Release for the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BP

blood pressure

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- GGT

gamma-glutamyltransferase

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- SREBF1

Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Transcription Factor

- DNL

de novo lipogenesis

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose

Writing Assistance: None

Author Contributions:

Jonathan A. Africa – study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript

Cynthia A. Behling – study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Elizabeth M. Brunt – acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Nan Zhang – statistical analysis; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Yunjun Luo – statistical analysis; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Alan Wells – statistical analysis; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Jiayi Hou – statistical analysis; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Patricia H. Belt – acquisition of data; study supervision; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Rohit Kohil – acquisition of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Joel E. Lavine – acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; study supervision

Jean P. Molleston – acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Kimberly P. Newton – acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Peter F. Whitington – acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Jeffrey B. Schwimmer –study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1388–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo P, Lindor KD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(Suppl):S186–S190. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42(3):641–649. doi: 10.1002/hep.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, et al. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):913–924. doi: 10.1002/hep.23784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwimmer JB, Zepeda A, Newton KP, et al. Longitudinal assessment of high blood pressure in children with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaskiewicz K, Rzepko R, Sledzinski Z. Fibrogenesis in fatty liver associated with obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(3):785–788. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter-Kent C, Brunt EM, Yerian LM, et al. Relations of steatosis type, grade, and zonality to histological features in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52(2):190–197. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181fb47d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalasani N, Wilson L, Kleiner DE, et al. Relationship of steatosis grade and zonal location to histological features of steatohepatitis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48(5):829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(9):2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig J, Viggiano T, McGill D, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sicklick JK, Li YX, Jayaraman A, et al. Dysregulation of the Hedgehog pathway in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):748–757. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicklick JK, Li YX, Choi SS, et al. Role for hedgehog signaling in hepatic stellate cell activation and viability. Lab Invest. 2005;85(11):1368–1380. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swiderska-Syn M, Suzuki A, Guy CD, et al. Hedgehog pathway and pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;57(5):1814–1825. doi: 10.1002/hep.26230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebhardt R, Hovhannisyan A. Organ patterning in the adult stage: The role of Wnt/??-catenin signaling in liver zonation and beyond. Dev Dyn. 2010;239(1):45–55. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebhardt R, Matz-Soja M. Liver zonation: Novel aspects of its regulation and its impact on homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8491–8504. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behari J, Li H, Liu S, et al. B-Catenin Links Hepatic Metabolic Zonation With Lipid Metabolism and Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(12):3284–3298. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehwald N, Tao G, Jang KY, et al. B-Catenin Regulates Hepatic Mitochondrial Function and Energy Balance in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):754–764. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzmán M, Castro J. Zonation of fatty acid metabolism in rat liver. Biochem J. 1989;264(1):107–113. doi: 10.1042/bj2640107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleicher J, Tokarski C, Marbach E, et al. Zonation of hepatic fatty acid metabolism - The diversity of its regulation and the benefit of modeling. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2015;1851(5):641–656. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolinsky VW, Gilham D, Alam M, et al. Triacylglycerol hydrolase: role in intracellular lipid metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(13):1633–1651. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehner R, Cui Z, Vance DE. Subcellullar localization, developmental expression and characterization of a liver triacylglycerol hydrolase. Biochem J. 1999;338(Pt 3):761–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwimmer JB. Clinical advances in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2016;63(5):1718–1725. doi: 10.1002/hep.28441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE, Wilson LA, et al. In Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Cysteamine Bitartrate Delayed Release Improves Liver Enzymes but Does Not Reduce Disease Activity Scores. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1141–1154.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.