Abstract

We report on the physicochemical effects resulting from incorporating a 5-(3-aminopropyl) side chain onto a 2′-deoxyuridine (dU) residue in a short DNA hairpin. A combination of spectroscopy, calorimetry, density and ultrasound techniques were used to investigate both the helix–coil transition of a set of hairpins with the following sequence: d(GCGACTTTTTGNCGC) [N = dU, deoxythymidine (dT) or 5-(3-aminopropyl)-2′-deoxyuridine (dU*)], and the interaction of each hairpin with Mg2+. All three molecules undergo two-state transitions with melting temperatures (TM) independent of strand concentration that indicates their intramolecular hairpin formation. The unfolding of each hairpin takes place with similar TM values of 64–66°C and similar thermodynamic profiles. The unfavorable unfolding free energies of 6.4–6.9 kcal/mol result from the typical compensation of unfavorable enthalpies, 36–39 kcal/mol, and favorable entropies of ∼110 cal/mol. Furthermore, the stability of each hairpin increases as the salt concentration increases, the TM-dependence on salt yielded slopes of 2.3–2.9°C, which correspond to counterion releases of 0.53 (dU and dT) and 0.44 (dU*) moles of Na+ per mole of hairpin. Absolute volumetric and compressibility measurements reveal that all three hairpins have similar hydration levels. The electrostatic interaction of Mg2+ with each hairpin yielded binding affinities in the order: dU > dT > dU*, and a similar release of 2–4 electrostricted water molecules. The main result is that the incorporation of the cationic 3-aminopropyl side chain in the major groove of the hairpin stem neutralizes some local negative charges yielding a hairpin molecule with lower charge density.

INTRODUCTION

DNA is normally considered a stiff rod-like molecule with a persistent end-to-end distance of >100 bp (1). Despite this apparent rigidity, many DNA affinity binding proteins, including histones, can introduce very significant non-linear distortions in DNA (2,3). Several distinct mechanisms have been proposed to account for the distortion induced by DNA binding proteins and clearly different proteins can utilize different bending pathways. A feature of some DNA bending proteins is the introduction of cationic side chains, e.g. Arg and Lys, at the center of the bend or kink. A well-studied DNA bending protein is the catabolite activating protein (CAP) transcription factor, which induces a 45° kink in the DNA at the TG step in its TGTGA conserved binding sequence (4). These TG steps are well conserved on both sides of the dyad axis in DNA binding sites so the CAP dimer bends the DNA by 90°. Based on the final structure, it is reasonable to assume that the initial event in the binding of CAP to DNA involves H-bonds between Arg and Glu residues on the protein and G and C nucleotides at the TG step that is at the center of the kinked region. As a consequence of the kinking, salt bridges and additional H-bonds can then form at sequences distal to the bent region. In an effort to understand the effects of basic amino acid side chains in protein-mediated bending, 5-(ω-aminoalkyl)-2′-deoxyuridine substitutions were used to mimic the interactions of basic amino acids with DNA (5,6). Using electrostatic footprinting and molecular modeling, the location of the cationic sidechain has been determined to be in the major groove toward the 3′-side (7,8). Significantly, when 5-(ω-aminoalkyl)-2′-deoxyuridine substitutions were appropriately phased with an intrinsically bent A-tract, they caused aberrant gel mobility, presumably due to the induction of non-linear DNA regions (5,6).

In order to specifically understand how the positioning of cationic charge in the major groove affects local DNA structure, a detailed thermodynamic characterization of DNA containing a single 5-(3-aminopropyl)-2′-deoxyuridine (dU*) residue is necessary. In this work, we are incorporating specific chemical groups in the DNA bases of short oligonucleotides that form intramolecular hairpins. Single-stranded hairpins are good thermodynamic models to mimic the pseudo-first-order helix–coil transition of natural DNA polymers. The main advantage for using these molecules is that they are small with an ellipsoidal shape and their helix–coil transitions are unimolecular that take place in a two-state fashion at convenient experimental temperatures. In addition, the small size of these molecules allows us to exclusively investigate the local contributions of the chemical incorporation of cationic chains in DNA, excluding the contributions of adjacent long double helical arms.

Specifically, we have used a combination of temperature-dependent UV spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) techniques to investigate the helix–coil transition of a set of hairpins with the following sequence: d(GCGACTTTTTGNCGC), where N represents 2′-deoxyuridine (dU), deoxythymidine (dT) or dU* (Fig. 1). We also used density and ultrasonic techniques to characterize the overall hydration of each hairpin and their interaction with Mg2+ ions. The comparison of thermodynamic profiles yields the specific energetic and hydration contribution for placing a 3-aminopropyl side chain or methyl group, on a deoxyuridine position located in the major groove and at the stem of a small DNA hairpin loop. The results show that the main effect of the amino charge at the end of this chain is to neutralize local negative charge.

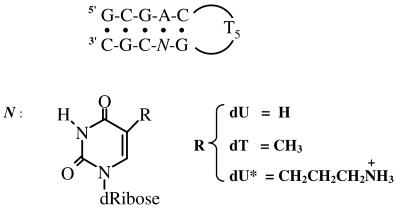

Figure 1.

Sequence of deoxyribonucleotide and structure of base modifications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The phosphoramidite derivative of dU* was prepared as previously described (9,10). All oligodeoxyribonucleotides were synthesized in University of Nebraska Medical Center, the Eppley Institute Molecular Biology Shared Resource, purified by reverse phase HPLC, desalted on a G-10 Sephadex column using a triethylammonium carbonate buffer and lyophilized to dryness. The dry oligomers were then dissolved in the appropriate buffer. For simplicity, each hairpin is designated as follows: ‘dU’ for the control hairpin, d(GCGACTTTTTGUCGC), ‘dT’ for d(GCGACTTTTTGTCGC) and ‘dU*’ for the hairpin containing the 5-(3-aminopropyl)dU or d(GCGACTTTTTGU*CGC). The extinction coefficients of oligonucleotides were calculated in water from the tabulated values of the monomer and dimer nucleotides (11) at 260 nm and 25°C. These values were then estimated in the random coil state at high temperatures using a procedure reported earlier (12). The molar extinction coefficient for each oligonucleotide is 1.32 × 105 M–1 cm–1 at 90°C. The buffer solutions used consisted of 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0, adjusted to the desired ionic strength with NaCl, or 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5 for the density and ultrasound experiments. MgCl2 and all other chemicals were reagent grade.

Temperature-dependent UV spectroscopy

Absorption versus temperature profiles (melting curves) for the helix–coil transition of DNA hairpins were obtained with a thermoelectrically controlled UV/Vis Aviv 14DS spectrophotometer, interface to a PC for data acquisition and analysis. The temperature was scanned at a heating rate of ∼0.6°C/min. Analysis of melting curves yields the helix–coil transition temperature, TM, and van’t Hoff enthalpies, ΔHvH (13). Melting curves as a function of strand and salt concentrations were obtained to confirm the intramolecular formation of each hairpin and to determine the thermodynamic release of counterions, ΔnNa+, accompanied their helix–coil transition.

Differential scanning calorimetry

The heat of unfolding of each molecule was measured with the MC-2 differential scanning calorimeter from Microcal Inc. (Northampton, MA). A typical experiment consists of obtaining a heat capacity profile of a DNA solution against a buffer solution. For the analysis of the experimental data, a buffer versus buffer scan is subtracted from the sample versus buffer scan; both scans in the form of mcal/s versus temperature were converted to mcal/°C versus temperature by dividing each experimental data point by the corresponding heating rate. Integration of the resulting curve, ∫ΔCpdT, and normalization for the number of moles yields the molar unfolding enthalpy, ΔHcal, which is independent of the nature of the transition; the molar entropy, ΔScal is obtained by a similar procedure, ∫(ΔCp/T)dT. The free energy at any temperature T is then obtained with the Gibbs equation: ΔG°cal(T) = ΔHcal – TΔScal, which assumes similar heat capacities for the hairpin and random coil states. Furthermore, the nature of the helix–coil transition is obtained by inspecting the ΔHvH/ΔHcal ratio; a value of nearly 1 indicates a two-state transition (13).

Measurement of hydration parameters

Ultrasonic velocity measurements were made with a home-built instrument, based on the resonator method (14,15), using two cells differentially and in the frequency range of 7–8 MHz. The molar increment of ultrasonic velocity, A, is defined by the relationship: A = (U – Uo)/(UoC), where U and Uo are the ultrasonic velocities of the solution and solvent, respectively, and C is the concentration of solute. In the acoustical titrations of each hairpin with Mg2+, 2–5 µl aliquots of MgCl2 are added stepwise to 700 µl hairpin solution. Mixing was performed directly with a built-in magnetic stirrer (15). The resulting A values were corrected for the contribution of salt concentration by carrying out similar titrations of the buffer. The ΔA values are calculated with the relationship: ΔA = A – A0, where A and A0 are the molar increment of ultrasonic velocity of the Mg2+–hairpin and hairpin solutions, respectively.

The density of each hairpin solution was measured with a DMA-602 densimeter (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) with two 200 µl cells. The apparent molar volume, ΦV, is calculated using the equation (16): ΦV = M/ρ – (ρ – ρo)/(ρoC), where ρo and ρ are the density of the solvent and solution, respectively, and M is the molecular weight of the hairpin. The molar volume change, ΔΦV, accompanying the interaction of Mg2+ with each hairpin is calculated using the equation ΔΦV = ΦV – ΦVo, where ΦV and ΦVo are the apparent molar volume of the Mg2+–hairpin and hairpin solutions, respectively. All solutions were prepared by weight using a microbalance and special precautions were taken to prevent solvent evaporation. The molar adiabatic compressibility, ΦKS, is obtained from the relationship (17): ΦKS = 2βo(ΦV – A – M/2ρo), where βo is the adiabatic compressibility coefficient of the solvent. Similarly, the change in the molar adiabatic compressibility, ΔΦKS, is determined from the ΔA and ΔΦV according to the relationship: ΔΦKS = 2βo(ΔΦV – ΔA).

Background of hydration parameters

The following relationships (18): ΦV = Vm + ΔVh and ΦKS = Km + ΔKh, provide a molecular interpretation for the absolute measurement of ΦV and ΦKS, as follows. The Vm and Km terms are the intrinsic molar volume and intrinsic molar compressibility, respectively, of the solute. The ΔVh term represents the hydration contribution of the change in the volume of water that surrounds a solute. The ΔKh term is the hydration contribution of the change in the compressibility of water around a solute and the compressibility of the void volumes between the solute and of the surrounding water. In the ΦKS values of oligodeoxynucleotides, the contribution of Km is small relative to their hydration terms. Therefore, the ΦKS value simply reflects the hydration contribution, i.e. ΦKS = ΔKh. In a similar way, the ΔΦV and ΔΦKS parameters of Mg2+ binding to oligonucleotides can be expressed in terms of their sole hydration contributions: ΔΦV = ΔΔVh and ΔΦKS = ΔΔKh, this assumes that the DNA conformation does not change.

RESULTS

UV and calorimetric unfolding of hairpin loops

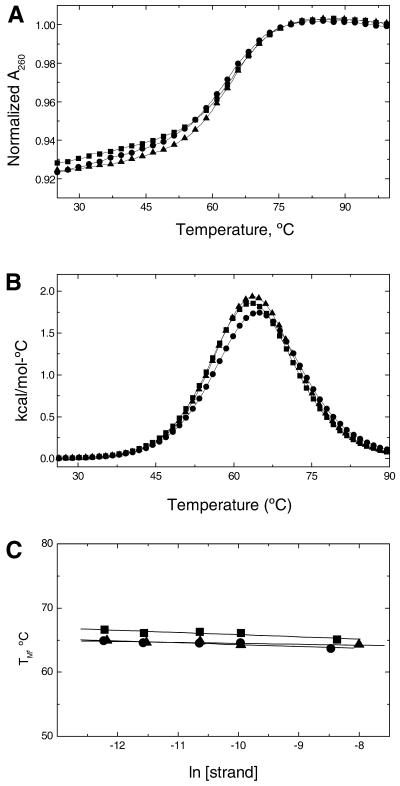

For the exclusive formation of single-stranded hairpins, the TM value is expected to be independent of strand concentration, which would mean that intramolecular hairpins form at low temperatures. In addition, intramolecular hairpin loops will have low hyperchromicity and high TM values. To confirm the molecularity of these hairpins, the helix–coil of each molecule was investigated as a function of strand concentration. The melting curves were performed in the strand concentration range of 5–250 µM. The UV melting of all three molecules at 260 nm occurs in broad monophasic transitions with average hyperchromicities of ∼8.7% (Fig. 2A). Typical excess heat capacity versus temperature profiles (Fig. 2B) indicate that all transitions are monophasic and take place without changes in the heat capacity of the initial and final states. The TM value dependence on strand concentration of these techniques is shown in Figure 2C. Similar TM values are obtained in this concentration range for each oligodeoxynucleotide, confirming the formation of single-stranded hairpins at low temperatures. Furthermore, the thermal stability of the hairpins follows the order: dU (63.7°C) < dU* (64.3°C) < dT (65.1°C), and similar ΔHcal values of 36–39 kcal/mol are obtained (Table 1). The comparison of ΔHvH, determined from the shape of the calorimetric melting curves, and ΔHcal allows us to draw conclusions about the nature of the transitions (13). We obtained ΔHvH/ΔHcal ratios of 1.05–1.11 that indicate all three hairpins melt in two-state transitions.

Figure 2.

Thermodynamic characterization of the helix–coil transition of dU (circles), dT (squares) and dU* (triangles) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7. (A) UV melting curves at oligonucleotide concentrations of 5 µM. (B) DSC curves at oligonucleotide concentrations of ∼225 µM (in strands). (C) Dependence of TM on strand concentration.

Table 1. Complete thermodynamic parameters for the formation of hairpins at 20°C.

| Hairpin |

Hyp.(%) |

TM(°C) |

ΔG°cal(kcal/mol) |

ΔHcal(kcal/mol) |

TΔScal(kcal/mol) |

ΔnNa+(per mol) |

ΦV(cm3/mol) |

ΦKS × 104(cm3/bar-mol) |

| dU |

8.9 |

63.7 |

–6.8 |

–39.0 |

–32.2 |

0.54 |

123 |

–13.0 |

| dT |

8.4 |

65.1 |

–6.4 |

–36.0 |

–29.6 |

0.52 |

127 |

–12.8 |

| dU* | 8.8 | 64.3 | –6.9 | –39.0 | –32.1 | 0.44 | 131 | –12.6 |

Standard thermodynamic parameters obtained in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7, while the hydration parameters in 10 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5. Experimental errors for each parameter are indicated in parenthesis as follows: TM (±0.5°C), ΔG°cal (±5%), ΔHcal (±5% kcal/mol), TΔScal (±5%), ΔnNa+ (±0.02), ΦV (±1 cm3/mol) and ΦKS.(±1.5 × 10–4 cm3/bar-mol). ΦV and ΦKS are calculated per nucleotide units.

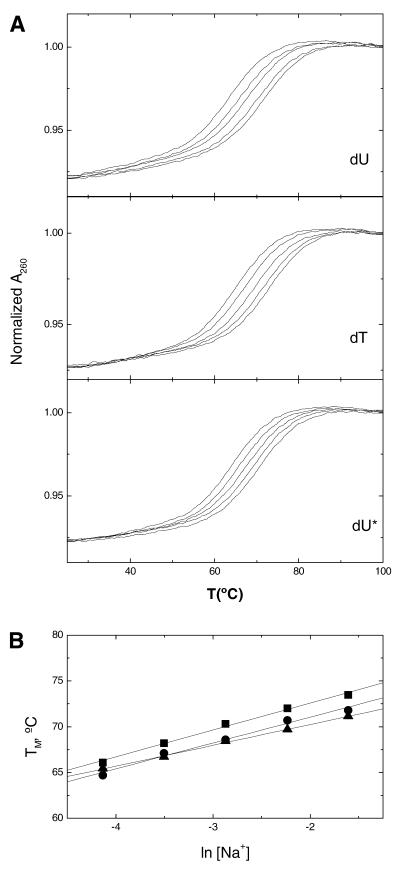

Thermodynamic release of counterions

For each hairpin, increasing the concentration of Na+ from 16 to 200 mM resulted in the shift of the melting curves to higher temperatures (Fig. 3A). The increase in salt concentration shifted the hairpin–random coil equilibrium towards the conformation with higher charge density parameter. The TM dependence on salt concentration for each hairpin is shown in Figure 3B. A linear dependence was obtained with slope values in the range of 2.3–2.9°C. The differential binding of ions for the helix–coil transition of a hairpin, ΔnNa+, was calculated from the relationship (19): ∂(ln K)/∂[ln (Na+)] = ΔnNa+, where K is the equilibrium constant and the (Na+) term is the ionic activity of sodium. Using the chain rule, [∂(ln K)/∂TM][∂TM/∂[ln (Na+)] = ΔnNa+, and the van’t Hoff equation, ∂(ln K)/∂T = ΔH/RT2, we obtained: ∂TM/∂(ln [Na+]) = 0.9(RTM2/ΔHcal)ΔnNa+. The ∂TM/∂(ln [Na+]) term in this relationship corresponds to the slope of the lines in Figure 3B, and 0.9 is a proportionality constant of converting mean ionic activities into concentrations. The term in parenthesis was obtained from DSC experiments, and R is the gas constant. We obtained ΔnNa+ values or counterion releases of 0.44 mol Na+/mol hairpin for the dU* hairpin and an average of ∼0.53 mol Na+/mol hairpin for the dU and dT hairpins.

Figure 3.

UV melting curves of oligonucleotides, at constant strand concentration of 5 µM, as a function of salt concentration in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7. (A) Typical melting curves over a NaCl concentration range of 16–200 mM. (B) Dependence of TM on salt concentration, dU (circles), dT (squares) and dU* (triangles).

Thermodynamic profiles for the formation of hairpins

The free energy values were calculated at 20°C from the Gibbs equation, using the enthalpies and entropies obtained in calorimetric melting experiments: ΔG°cal = ΔHcal – 293.15 ΔScal. In the Gibbs equation, both the enthalpy and entropy are assumed independent of temperature. Table 1 lists standard thermodynamic profiles for the formation of each hairpin at 20°C, and the data indicate that at this temperature all three oligodeoxynucleotides are ordered and exist as hairpins. The favorable ΔG°cal value for the formation of each hairpin resulted from the characteristic partial compensation of a favorable enthalpy and unfavorable entropy terms. The favorable ΔHcal values result from the formation of H-bonds and base pair stacks in the stem, whereas the unfavorable entropy values indicates an ordering of the systems due to an uptake of counterions and water molecules (see below).

Overall hydration properties of hairpins

We used density and ultrasonic techniques to measure the volume and compressibility parameters that characterize the hydration of each hairpin. The absolute values of ΦV and ΦKS are shown in the last two columns of Table 1. All three ΦV values are positive, which is expected because the value corresponds to the sum of two contributions: the intrinsic volume or van der Waals volume of each molecule and its associated volume of hydration. The magnitude of these ΦV values follows the order: dU* > dT > dU, and the differences were small but significant (Table 1). However, this trend is consistent with the size of the uridine modifications in the 5 position: 3-aminopropyl > methyl > hydrogen. On the other hand, the ΦKS values were negative and corresponded to the much larger contribution of water in the hydration shell of these hairpins. These values followed a similar trend as the ΦV values (Table 1) but their magnitudes were within experimental uncertainties. Therefore, these compressibility parameters reflect a similar hydration level for all three hairpins; and in the absence of compensating effects, if any, indicate that the chemical substitutions in these hairpins have similar hydration contributions.

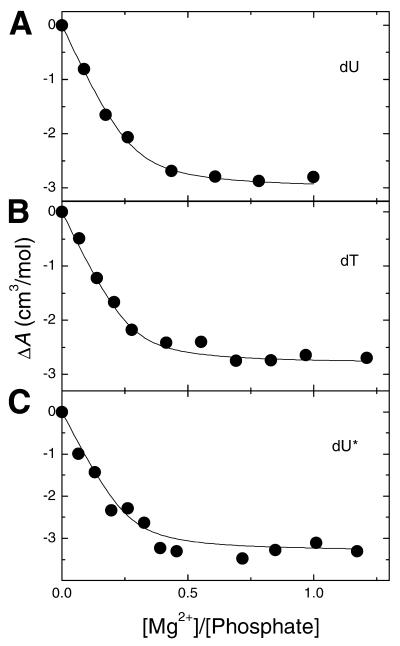

Hydration effects accompanying the binding of Mg2+ to hairpins

Acoustical titrations for the addition of Mg2+ to each hairpin are shown in Figure 4. The resulting curves are actually Mg2+-binding isotherms and their shapes were very similar. However, some small differences occur in the initial slopes and overall amplitude of the curves. The initial slopes were proportional to the Mg2+–nucleic acid binding affinities (KMg2+), although the overall amplitude at [Mg2+]/[Phosphate] saturation levels were ∼0.6, and correspond to the total dehydration effect of Mg2+ binding, ΔA (Fig. 4). The interaction of Mg2+ with each hairpin yielded negative values of ΔA, which indicate a release of water molecules. This water release corresponds to the net hydration changes of the Na+–Mg2+ exchange that takes place in the ionic atmosphere of the hairpin. A quantitative evaluation of both KMg2+ and ΔA values is determined from fitting the Mg2+-binding isotherms interactively using a binding model where Mg2+ interacts with each hairpin containing one type of identical and independent binding sites (20). The fitting procedure is characterized by three parameters: KMg2+, ΔAMg2+, and the apparent number of Mg2+ sites, nMg2+. This procedure is simplified by obtaining the nMg2+ values from the X-intercept of the experimental ultrasonic titrations (20). We obtained an average ΔAMg2+ value of –10.5 ml/mol of Mg2+ and KMg2+ values of ∼9.5 × 103 M–1. The strength of Mg2+ binding to the hairpins is lowest with the dU* hairpin and consistent with its lower release of Na+ ions. These effects suggest a lower charge density parameter for the dU* hairpin. The hydration parameters, ΔΦV and ΔΦKS, of Mg2+ binding to hairpins are shown in Table 2. All values were positive (Table 2) and consistent with the reported effects derived from the values of ΔA. Mg2+ binding releases water molecules from the hydration shells of the free Mg2+ ions and/or interacting nuclei acid atomic groups. The similarity of the ΔΦV and ΔΦKS values, among the three hairpins, indicates a similar release of water molecules.

Figure 4.

Ultrasonic titration curves of DNA hairpins with MgCl2 in 10 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5 and at oligonucleotide concentrations of ∼150 µM (in strands).

Table 2. Binding and hydration parameters for the interaction of Mg2+ with hairpins at 20°C.

| Hairpin |

ΔA (ml/mol) |

nMg2+ (mol/mol P) |

KMg2+ (M–1) |

ΔΦV (cm3/mol) |

ΔΦKS × 104 (cm3/bar-mol) |

k × 10–4 (bar) |

| dU |

–3.0 |

0.28 |

10.0 × 103 |

9.7 |

18.3 |

0.53 |

| dT |

–2.8 |

0.28 |

9.7 × 103 |

8.6 |

16.7 |

0.51 |

| dU* | –3.3 | 0.27 | 8.7 × 103 | 9.8 | 18.1 | 0.54 |

All experiments were done in 10 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5. Experimental errors for each parameter are indicated in parenthesis as follows: ΔA (±10%), nMg2+ (±10%), KMg2+ (±20%), ΔΦV (±5%), ΔΦKS.(±8%) and k (±13%).

DISCUSSION

Formation of intramolecular hairpins at low temperatures

The exclusive formation of monomolecular hairpin loops at low temperatures for all three sequences is confirmed with the following experimental observations. First, their experimental TM values are ∼65 and ∼20°C higher than the estimated TM values of the corresponding bimolecular duplexes with an internal loop of 10 thymine residues. Secondly, the TM value of each molecule remains the same over a 40-fold change in strand concentration and has a slight dependence on salt concentration. The average release of counterions is 0.50 mol Na+/mol hairpin, which is indicative of their low charge density. Thirdly, the calorimetric unfolding enthalpy is 37.0 kcal/mol in low salt, which is characteristic of the melting behavior of short double helical stems. This is in good agreement with the predicted enthalpy values of 35.1–36.8 kcal/mol, obtained from DNA nearest-neighbor parameters (21,22).

Thermodynamics of forming DNA hairpins with single base modifications

We have investigated three DNA hairpins containing specific substitutions at the 5 position of uridine: -H, -CH3 and -CH2CH2CH2N+H3, and complete thermodynamic and hydration profiles for the formation of each hairpin at 20°C are listed in Table 1. For a better understanding of these profiles, it is important to emphasize the physical factors involved in their favorable formation, namely contributions from base pairing, base pair stacking, hydration and counterion binding. These non-covalent interactions depend on the specific chemical composition of the strands used and overall conformation. The formation of each hairpin is accompanied by favorable free energy terms, which results from an enthalpy–entropy compensation, the uptake of ions and immobilization of water molecules (Table 1). The resulting enthalpies correspond to the net balance of the following contributions: base pairing and base pair stacking interactions of the stem and stacking of the loop bases at the stem–loop interface. The uptake of electrostricted water molecules by the hairpin stem and the release of structural water from the thymine bases prior to forming constrain loops may also contribute favorably while the uptake of counterions has a negligible heat contribution (23). The unfavorable entropy terms correspond to contributions of forming a higher ordered hairpin–loop structure, resulting from the intramolecular association of a random coil, and a net uptake of water and counterions. Therefore, the similar standard thermodynamic profiles (ΔG°, ΔH and ΔS) for hairpin folding indicate similar base pairing and base pair stacking contributions in all hairpins. This suggests that all three hairpins have a similar conformation and the incorporation of a methyl group or of an aminopropyl group on uracil has a negligible effect on their conformation.

Incorporation of the charged aminopropyl chain yields a lower uptake of counterions

The combined UV and calorimetric melting experiments yielded, in the formation of hairpins, counterion uptakes of 0.44 mol Na+/mol hairpin for the dU* hairpin, and an average of ∼0.53 mol Na+/mol hairpin for the dU and dT hairpins. Using these values, we estimate 0.055 mol Na+/mol phosphate and 0.066 mol Na+/mol phosphate, respectively, if only the eight phosphate groups of the stem are taken into account. Relative to the value of 0.17 mol Na+/mol phosphate for longer duplex DNA molecules, these values are low but consistent with the formation of 5 bp in the hairpin stems (24). The significant observation is the lower uptake of counterions for the hairpin containing the dU* modification. This shows that the positively charged aminopropyl chain at pH 7 is partially neutralizing the negative charges in the stem of the dU* hairpin. The actual degree of neutralization of negative phosphate charge by the aminopropyl group may be estimated from the 0.09 mol Na+/mol hairpin differential uptake of counterions, and assuming all three hairpins have similar conformation and base pair stacking interactions. We estimate an ∼14% higher phosphate neutralization for the local placement of the aminopropyl chain in the major groove of the stem of the dU* hairpin. We stressed that the aminopropyl group does not form a salt bridge with the phosphate backbone (7,8,25). The charge neutralization might take place by the proposed electrostatic mechanism of Rouzina and Bloomfield (26). In this mechanism, the localization of the cationic aminopropyl group in the major groove of DNA electrostatically repels sodium counterions associated with the anionic phosphates yielding an unscreened backbone. In turn, the weakly screened phosphates then interact strongly with the tethered cation causing a collapse of the major groove. This scenario is consistent with our thermodynamic results and nicely also explains how the ω-aminoalkyl side chains induce DNA bending.

All three hairpin molecules have a similar hydration state

We showed that each hairpin yielded negative compressibility parameters, which indicate an uptake of water molecules. The overall effects are small but similar and consistent with the similar conformation of each hairpin with small chemical modifications, i.e. incorporation of additional 3–12 atomic groups out of ∼420 atomic groups of a hairpin molecule. The magnitude of the molar volume of a hairpin molecule is attributed to both its van der Waals volume and the volume of its hydration shell. The magnitude of the molar compressibility is proportional only to the compressibility of the hydration shell because the van der Waals volume is considered incompressible. The contribution of water in the hydration shell of any molecule depends on the type of hydrating water, and this could be structural (or hydrophobic) around organic moieties and non-polar atomic groups or electrostricted around charges and polar atomic groups. In the case of DNA hairpin loops containing a stem of stacked base pairs and a loop of constrained thymines, the stem will have a higher immobilization of electrostricted water due to its increased charged density parameter while the loop immobilizes a higher degree of structural water due to a larger exposure of bases to the solvent. Hydration contributions related to the interaction of sodium ions with B-DNA are considered negligible, their deep occupancy in the minor groove has been considered very low (27) and, on average, the ions keep their hydration shells (28). The type of water may be estimated from the slope of the line of a plot of ΦV versus ΦKS, which yielded a slope of 20 × 104 bar (data not shown). The magnitude of this slope is very large because of the small trends obtained with both parameters but it is in the direction that suggests a higher uptake of structural water. However, the overall uptake of water molecules by these hairpin molecules is supported by density investigations of similar DNA hairpins (29).

Hydration effects accompanying the binding of Mg2+ to hairpins

The interaction of Mg2+ with a nucleic acid duplex has been considered to be electrostatic (28,30,31). For this reason, Mg2+ is used to probe the effective charge density of each hairpin and its overall hydration. The magnitudes of the KMg2+ values are consistent with its electrostatic nature. The lower KMg2+ value for the dU* hairpin indicates that this hairpin has a lower charge density parameter, consistent with the additional neutralization of negative charge by the aminopropyl chain.

For the interpretation of the hydration effects of Mg2+ binding, it is important to take into account contributions from the effective charge density, conformation, sequence and overall hydration of the hairpin molecule. In addition, specific effects such as the formation of inner-sphere complexes when Mg2+ chelates specific atomic groups of the oligonucleotide should be considered. For the latter case, the resulting ΔΦV and ΔΦKS values of Mg2+ binding are compared to similar parameters for the formation (or dissociation) of complexes of metal ions with charged molecules with known three-dimensional structures. The similarity of the ΔΦV (and ΔΦKS) values of Mg2+ binding among the three hairpins indicates a similar release of water molecules from the hydration shells of the participating atomic groups. The type of hydrating water, structural or electrostricted, responsible for the hydration effects in the process of Mg2+ binding may be characterized empirically by their absolute value of k (equal to ΔΦV/ΔΦKS) (32–34). Examples are the formation of cation–EDTA complexes, characterized by k values of 0.34–0.39 × 104 bar (33). The formation of nucleic acid duplexes with higher non-polar character, are characterized with k values of 0.75 × 104 bar (34). In this work, Mg2+ binding yields ΔΦV/ΔΦKS ratios of 0.53 × 104 bar, indicating the participation of electrostricted water. Furthermore, we used the following parameters, ΔV = 2.5 cm3/mol and ΔΦKS = 8.2 × 10–4 cm3/bar-mol (35,36), to estimate the number of electrostricted water molecules involved in this interaction. The resulting ΦV and ΔΦKS values are divided by these parameters to yield a release of 2–4 electrostricted water molecules for the condensation of one Mg2+ ion. The hydration contribution of the displaced Na+ ions is considered negligible. This release is the result of removing water molecules from polar and charged groups of the nuclei acid and from the Mg2+ ions. On the other hand, the magnitude of these hydration parameters may well suggest the formation of one Mg2+–DNA inner-sphere complex in the stem. This is due to helical stems adopting the B-conformation, which renders them more hydrated, and their high content of dG·dC base pairs favors the formation of inner-sphere complexes (20). Alternatively, these hydration parameters are probably not indicative of a singly-coordinated inner-sphere contact complex, but instead support the idea that Mg2+ binding to the stem of each hairpin only slightly relaxes the electrostricted region lying beyond the inner layers. Thus, the main contribution to the volume change of ion pairing is likely from the relaxation of the outer-electrostricted region, with the removal of contact waters giving only a relatively small contribution to the volume and compressibility parameters.

CONCLUSION

We investigated the physicochemical effects of the attachment of a 3-aminopropyl group onto the 5-position of dU in a short DNA hairpin. The unfolding of three hairpins (two as control hairpins) and their interaction with Mg2+ ions were investigated using melting, density and acoustical techniques. All three intramolecular hairpins unfold in two-state transitions with similar TM values and similar thermodynamic profiles. The favorable free energies of 6.4–6.9 kcal/mol result from the typical compensation of favorable enthalpies (36–39 kcal/mol) and unfavorable entropies (110 cal/mol). All three hairpins have similar hydration levels; however, the stability of each hairpin has a weak dependence on salt concentration, which yielded a smaller counterion release for the hairpin with the cationic side chain. Therefore, the presence of this chain in the major groove of the hairpin stem effectively neutralizes a higher degree of negatively charged phosphate groups. The electrostatic interaction of Mg2+ with each hairpin yielded a similar release of 2–4 electrostricted waters and binding affinities consistent with the lower charge density parameter of the hairpin containing the cationic chain. The overall results will serve as thermodynamic baselines in future investigations of the effects of incorporating charge groups in long DNA oligonucleotide duplexes.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Grants GM42223 (LAM), CA76049 (BG) from the National Institutes of Health, and Cancer Center Support Grant CA36727 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Hagerman P.J. (1988) Flexibility of DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem., 17, 265–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young M.A., Ravishanker,G., Beveridge,D.L. and Berman,H.M. (1995) Analysis of local helix bending in crystal structures of DNA oligonucleotides and DNA-protein complexes. Biophys. J., 68, 2454–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luger K., Mader,A.W., Richmond,R.K., Sargent,D.F. and Richmond,T.J (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz S.C., Shields,G.C. and Steitz,T.A. (1991) Crystal structure of a CAP–DNA complex: the DNA is bent by 90 degrees. Science, 253, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss J.K., Roberts,C., Nelson,M.G., Switzer,C. and Maher,L.J.,III (1996) DNA bending by hexamethylene-tethered ammonium ions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 9515–9520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss J.K., Prakash,T.P., Roberts,C., Switzer,C. and Maher,L.J.,III (1996) DNA bending by a phantom protein. Chem. Biol., 3, 671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang G., Encell,L., Nelson,M.G., Switzer,C., Shuker,D.E.G. and Gold,B. (1995) Role of electrostatics in the sequence-selective reaction of charged alkylating agents with DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 10135–10136. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dande P., Liang,G., Chen,F.-X., Roberts,C., Nelson,M.G., Hashimoto,H., Switzer,C. and Gold,B. (1997) Regioselective effect of zwitterionic DNA substitutions on DNA alkylation: evidence for a strong side chain orientational preference. Biochemistry, 36, 6024–6032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashimoto H., Nelson,M.G. and Switzer,C. (1993) Zwitterionic DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115, 7128–7134. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto H., Nelson,M.G. and Switzer,C. (1993) Formation of chimeric duplexes between zwitterionic and natural DNA. J. Org. Chem., 58, 4194–4195. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantor C.R., Warshow,M.M. and Shapiro,H. (1970) Oligonucleotide interactions. 3. Circular dichroism studies of the conformation of deoxyoligonucleotides. Biopolymers, 9, 1059–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marky L.A., Blumenfeld,K.S., Kozlowski,S. and Breslauer,K.J. (1983) Salt-dependent conformational transitions in the self-complementary deoxydodecanucleotide d(CGCGAATTCGCG): evidence for hairpin formation. Biopolymers, 22, 1247–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marky L.A. and Breslauer,K.J. (1987) Calculating thermodynamic data for transitions of any molecularity from equilibrium melting curves. Biopolymers, 26, 1601–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggers F. and Funck,T. (1973) Ultrasonic measurements with milliliter liquid samples in the 0.5–100 MHz range. Rev. Sci. Instrum., 44, 969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarvazyan A.P. (1982) Development of methods of precise ultrasonic measurements in small volume of liquids. Ultrasonics, 20, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millero F.J. (1972) The partial molal volumes of electrolytes in aqueous solutions. In Horn,R.A (ed.), Water and Aqueous Solutions. Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY, pp. 519–595.

- 17.Barnartt S. (1952) The velocity of sound in electrolytic solutions. J. Chem. Phys., 20, 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shio H., Ogawa,T. and Yoshihashi,H. (1955) Measurement of the amount of bound water by ultrasonic interferometer. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 77, 4980–4982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantor C.R. and Schimmel,P.R. (1980) Biophysical Chemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY.

- 20.Buckin V.A., Kankiya,B.I., Rentzeperis,D. and Marky,L.A. (1994) Mg2+ recognizes the sequence of DNA through its hydration shell. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 9423–9429. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslauer K.J., Frank,R., Blocker,H. and Marky,L.A. (1986) Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 3746–3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SantaLucia J.Jr (1998) A unified view of polymer, dumbbell and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marky L.A. and Kupke,D.W. (1989) Probing the hydration of the minor groove of A.T synthetic DNA polymers by volume and heat changes. Biochemistry, 28, 9982–9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rentzeperis D. (1994) PhD dissertation, New York University, NY.

- 25.Heystek L.E., Zhou,H.-Q., Dande,P. and Gold,B. (1998) Control over the localization of positive charge in DNA: The effect on duplex DNA and RNA stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 12165–12166. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouzina I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1998) DNA bending by small, mobile multivalent cations. Biophys. J., 74, 3152–3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denisov V.P. and Halle,B. (2000) Sequence-specific binding of counterions to B-DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 629–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning G. (1978) The molecular theory of polyelectrolyte solutions with applications to the electrostatic properties of polynucleotides. Q. Rev. Biophys., 11, 179–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rentzeperis D., Kharakoz,D.P. and Marky,L.A. (1991) Coupling of sequential transitions in a DNA double hairpin: energetics, ion binding and hydration. Biochemistry, 30, 6276–6283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pezzano H. and Podo,F. (1980) Structure of binary complexes of mono- and polynucleotides with metal ions of the first transition group. Chem. Rev., 80, 365–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granot J., Feigon,J. and Kearns,D.R. (1982) Interactions of DNA with divalent metal ions. I. 31P-NMR studies. Biopolymers, 21, 181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lown D.A., Thirsk,H.R. and Lord Wynne-Jones (1968) Effect of pressure on ionization equilibria in water at 25°C. Trans. Faraday Soc., 64, 2073–2080. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kankia B.I., Funck.T., Uedaira,H. and Buckin,V.A. (1997) Volume and compressibility effects in the formation of metal-EDTA complexes. J. Sol. Chem., 26, 877–888. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kankia B.I. and Marky,L.A. (1999) DNA, RNA and DNA/RNA oligomer duplexes: A comparative study of their stability, heat, hydration and Mg2+ binding properties. J. Phys. Chem. B, 103, 8759–8767. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marky L.A. and Kupke,D.W. (2000) Enthalpy-entropy compensations in nucleic acids: contribution of electrostriction and structural hydration. Methods Enzymol., 323, 419–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millero F.J., Ward,G.K., Lepple,F.K. and Hoff,E.V. (1974) Isothermal compressibility of aqueous sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium sulfate and magnesium sulfate solutions from 0 to 45 °C at 1 atm. J. Phys. Chem., 78, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar]