Abstract

Some 5-HT2B fluorescent probes were obtained by tagging 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-propan-2-amine (DOI) with a subset of fluorescent amines. Some of the resulting fluorescent ligands showed excellent affinity and selectivity profiles at the 5-HT2B receptors (e.g. 12b), while retain the agonistic functional behaviour of the model ligand (DOI). The study highlighted the most salient features of the structure-activity relationship in this series and these were substantiated by a molecular modelling study based on a receptor-driven docking model constructed on the basis of the crystal structure of the human 5-HT2B receptor. One of the fluorescent ligands developed in this work, compound 12i, specifically labelled CHO-K1 cells expressing 5-HT2B receptors and not parental CHO-K1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. 12i enables imaging and quantification of specific 5-HT2B receptor labelling in live cells by automated fluorescence microscopy as well as quantification by measurements of fluorescence intensity using a fluorescence plate reader.

Introduction

The biogenic amine serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is one of the most versatile chemical messengers in the central and peripheral nervous systems1. In addition to its well-known role as a neurotransmitter2, regulating virtually all brain functions and neurophysiological processes, 5-HT controls critical functions3 within cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems. Consequently, serotonin has been implicated in the etiology of numerous disease states4 (e.g., depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive and panic disorders, migraine, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, eating disorders, vomiting and irritable bowel syndrome). The large diversity of functions of serotonin is paralleled by the pharmacological complexity of serotonin receptors5. Of the 14 mammalian 5-HT receptor subtypes, all but one (5-HT3) belong to the super-family of G protein-coupled-receptors (GPCRs)5, 6, which mediate most of the serotonin-based signalling network by receiving and modulating complex information6, 7.

The 5-HT2 receptor family comprises three closely related receptor subtypes8, 9, namely 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C, that are the molecular targets of prominent drugs acting in different therapeutic areas1–4, 9–11 (e.g., schizophrenia, depression, hypertension, anxiety). 5-HT2 receptor subtypes mediate many of the central and peripheral physiological functions of serotonin1–4 and they couple preferentially to Gq/11 to increase the hydrolysis of inositol phosphates (IPs) and elevate cytosolic Ca2+. This similar functional behaviour is supported by a high structural homology8, 9. 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors share approximately 46–50% amino acid sequence identity, with the homology being higher than 70% within the transmembrane domains (which contain the 5-HT2 binding pocket)8, 9. Accordingly, the development of highly selective ligands that target a particular 5-HT2 receptor subtype constitutes a considerable challenge. The recent resolution of the crystal structure of the 5-HT2B receptor7 provides new opportunities for the rational discovery of novel small-molecule modulators of 5-HT receptors.

The 5-HT2B subtype remains one of the most attractive and enigmatic receptors amongst the 5-HT receptor superfamily12, 13, with key functional, signalling, and regulatory aspects remaining ambiguous. The involvement of this receptor in the development of migraine14, the modulation of the 5-HT transport system15, and the rewarding and reinforcing effects of the widely abused drug ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, MDMA) has been validated16. 5-HT2B receptor also participate in other relevant processes, particularly in the cardiovascular system where it regulates cardiac development and cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival17, 18. 5-HT2B activation has been associated with diverse pathologies19, 20 (e.g., cardiac hypertrophy and pulmonary hypertension). It has been shown that 5-HT2B activation, along with the inhibition of serotonin transporters, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of serotonin-induced valvular abnormalities20–22. In line with these observations, it has been demonstrated that norfenfluramine (a metabolite of the antiobesity drug fenfluramine that exhibits potent 5-HT2B agonist activity) and other 5-HT2B agonists used in the treatment of migraine induce valvular heart disease23–25. Similarly, it was recently verified that the use of the antiparkinsonian dopaminergic agonists cabergolide and pergolide (both of which also exhibit high 5-HT2B agonism) is associated with mitral, aortic, and tricuspid valvular heart disease26, 27. Accordingly, drugs that are able to activate 5-HT2B receptors and/or increase circulating serotonin levels are considered to be potential valvulophatic inducers and, as a consequence, 5-HT2B agonism is considered a dangerous off-target effect22, 27–29, thus hampering the promising therapeutic potential of 5-HT2B receptor28. However, our understanding of the role of 5-HT2B receptor and an in-depth knowledge of the processes triggered by ligand−5-HT2B receptor interactions in living cells are still limited due to the lack of ad hoc molecular probes.

The introduction of fluorescence-based techniques has progressed the study of GPCR pharmacology to the single cell level30. Fluorescent molecular probes have proven to be valuable tools that offer a wealth of relevant evidence31, 32, particularly the mapping or identification of ligand binding sites, ligand binding mechanisms, the physical nature of the binding pocket, the movement and internalization of receptors in living cells, and the localization and visualization of labelled receptors. Furthermore, fluorescent probes represent a safer, less expensive and faster alternative to radioligands. The extensive application of these techniques to GPCR research demands the development of fluorescently labelled GPCR ligands that have appropriate photochemical and pharmacological properties. A number of fluorescent probes have been described for 5-HT1A 33, 5-HT3 34 and 5-HT6 35 receptors but, to the best of our knowledge, reports concerning fluorescently-tagged 5-HT2 ligands have not been published to date. As part of a project aimed at developing molecular probes for the study of the 5-HT2 receptor family, we report here the development and optimization of fluorescent tools that selectively target 5-HT2B receptors. The new ligands combine good fluorescence properties with satisfactory affinity and selectivity; accordingly, these molecular probes can contribute to a better understanding of the physiological and pathological implications of 5-HT2B receptors.

Results and Discussion

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-propan-2-amine (DOI)36 was selected as the reference ligand to develop the fluorescent probes designed within this study. DOI is a partial agonist derived from the amphetamine chemotype and it is one of the most useful and better pharmacologically characterized molecular tools for the study of the 5-HT2-receptor family37, 38. In addition, the [125-I]-R-DOI radioligand is recognized as a reference standard for high throughput screening campaigns at 5-HT2 receptors39, 40. Recent findings have shown that DOI produces a super-potent (≈15 pM) blockade of the pro-inflammatory effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in primary aortic smooth muscle cells and animal models41, 42. These findings, which provided new evidence about the role of 5-HT2A receptors in inflammation, increase the demand for DOI-based fluorescent probes. For this study, it was decided to employ racemic DOI as reference, accordingly all molecular probes were synthesized and tested as racemates.

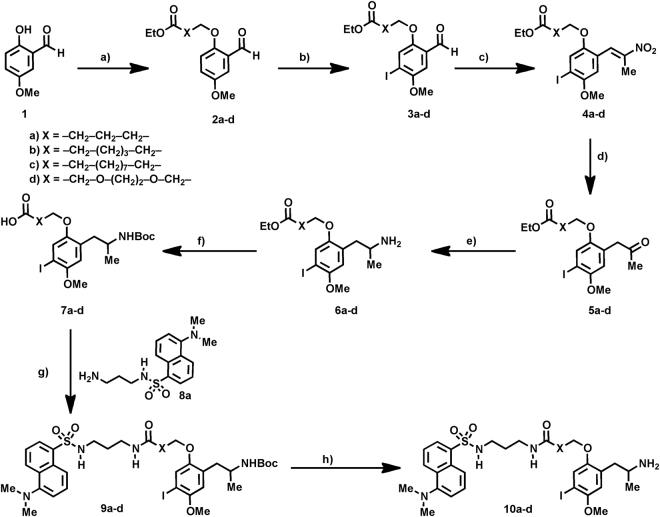

DOI is a well-recognized specific 5-HT2 ligand that, notwithstanding, exhibits weak selectivity within the 5-HT2 receptor family (5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C)36–38. Previous reports have evidenced the introduction of functionalized alkyl chains on the methoxy group at position 2 of the phenyl ring in DOI produces an increased 5-HT2B selectivity43. This structure-activity relationship trend encouraged us to explore the use of DOI-based derivatives for the development of fluorescent ligands for the 5-HT2B receptor. A set of acid-functionalized DOI derivatives (7a–d) bearing variable spacers on the oxygen atom at position 2 was synthesized (Fig. 1) according to previously described procedures44–48. With the aim of carrying out a preliminary evaluation of the biological repercussions of the different spacers, precursors 7a–d were transformed into the corresponding fluorescent derivatives 10a–d by reacting with a model dansyl amine (8a) and subsequent cleavage of the Boc groups (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the target fluorescent DOI analogues44–48. Reagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3, R–X, MeCN, 80 °C, 8 h. (b) I2, THF, rt, 24 h. (c) Me-NO2, AcOH, 100 °C, 6 h. (d) Fe, AcOH, 100 °C, 12 h. (e) NH4OAc, NaCNBH4, THF, 2 h. (f) (Boc)2O, THF, 0 °C, 3 h. (g) DCC, DCM, rt, 12 h (70–93%). (h) HCl/Dioxane, DCM, 0 °C, 2 h (50–78%).

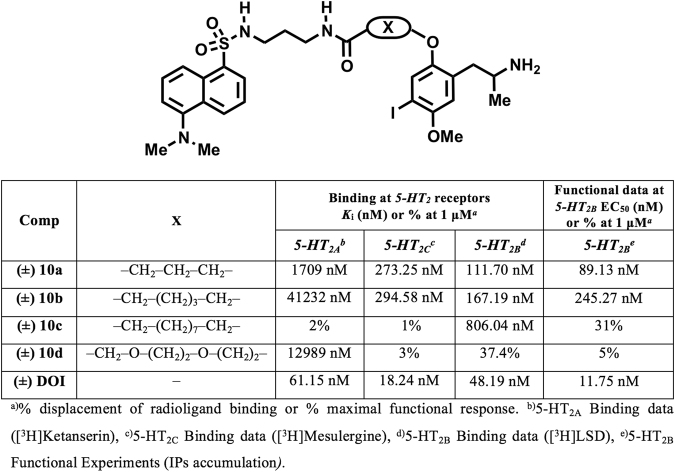

The fluorescent probes 10a–d contain the 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-propan-2-amine scaffold and the dansyl chromophore linked through variable spacers that differ in both length and composition (Fig. 2). The results of the pharmacological evaluation of the model fluorescently-tagged amides 10a–d at the 5-HT2 receptor family (5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C)49, 50 are presented in Fig. 2. All compounds were evaluated in binding experiments (see experimental part) and the results were compared with the biological activity determined for the reference ligand (DOI). Additionally, the functional activities (IPs accumulation)51 of the compounds at the 5-HT2B receptor were also determined (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Structural and pharmacological data at 5-HT2 receptors of model dansyl probes bearing different linkers (10a–d).

In agreement with previous findings43, it was verified that the introduction of alkyl chains on the oxygen atom at position 2 of the phenyl ring of the amphetamine scaffold produces derivatives that exhibit incipient 5-HT2B subtype selectivity (10a–d, Fig. 2). The drop observed in the 5-HT2A affinity is particularly noteworthy as this is in the micromolar range for all of the dansyl probes tested. Another remarkable trend identified on considering the biological data (Fig. 2) obtained for DOI derivatives bearing dansyl as a fluorescent tag (10a–d) is the importance of the spacer group linking the pharmacophore and the fluorophore. It was observed that elongation of the spacer has a negative effect on both the affinity and activity at the 5-HT2B receptor (Fig. 2), with the fluorescent probe bearing the propyl group (10a) displaying the most attractive affinity and selectivity profiles.

In an effort to shed light on the molecular determinants for the binding of the novel fluorescent probes, we used the recent crystallized structure of the 5-HT2B receptor (PDB ID: 4IB4)7 to create three-dimensional models of this receptor in complex with two fluorescent derivatives with different linker lengths: compound 10a (3 carbon linker) and 10b (5 carbon linker). The resulting complexes were embedded in a physiological environment consisting of a hydrated lipid bilayer and then subjected to extended molecular dynamics simulations with a total simulation time of 1.6 µs. A common binding pose was obtained for the DOI fragment for both simulated systems and this fragment is inserted deep into to the 5-HT2B receptor (Fig. 3, inset top panel). The protonated nitrogen of DOI establishes a strong electrostatic interaction with D3.32 whereas the aromatic ring is sandwiched in a hydrophobic environment formed by a valine in position 3.33 and two phenylalanines in positions 6.51 and 6.52. This tight binding results in a stable pose along the simulation, as reflected by low RMSD values of 0.761 Å (compound 10a) and 0.703 Å (compound 10b) with respect to the average structure (Fig. 3, lower panel). In contrast, the fluorescent tag that is linked to position 2 of the aromatic ring and reaches towards the extracellular side of the 5-HT2B receptor shows much higher dynamic variability around the average structure, with an RMSD of 2.144 Å for ligand 10a and 3.732 Å for compound 10b. The general higher fluctuation for both fluorescent probes is due to interaction with areas of higher flexibility in the extracellular loop region of the receptor. This situation is inevitable as the fluorescent tag needs to reach sufficiently far out of the receptor in order to avoid undesired quenching interactions with the receptor, which would give rise to a non-functional fluorescence probe.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional complexes of the fluorescent probes 10a (left) and 10b (right) bound to the 5-HT2B receptor obtained from extended molecular dynamics simulation with a total time of 1.6 μs (2 times × 800 ns). The upper panel highlights ligand-receptor interactions of a representative structure. The lower panel includes information about the dynamic properties and stability of the ligand binding by depicting frames each 50 ns along a total simulation time of 800 ns. The RMSD values are calculated for DOI or the fluorescent tag with respect to the average structure at 800 ns.

Despite this higher fluctuation, it was found that during the course of the simulation compound 10a (3 carbon linker) formed frequent polar interactions with the backbone of ECL 2 and Q7.32 via the SO2 group (Fig. 3, top left panel), which result in a stabilization of the fluorescent tag (RMSD 2.144 Å, bottom left panel). Such polar stabilization is reduced for compound 10b because the longer linker architecture (5 carbon linker) is not optimal for allowing this polar interaction. Such reduced stabilization could be a plausible explanation for the reduced binding affinity observed for compound 10b (5 carbon linker, Ki: 167.19 nM) compared to compound 10a (3 carbon linker, Ki: 111.70 nM). The model developed here predicts that compounds with a longer linker have reduced stabilizing interactions in the extracellular loop regions and therefore exhibit lower binding affinity. This prediction is consistent with the other experimental data. For example, compound 10c (9 carbon linker, Ki 806.04 nM) has a markedly lower binding affinity compared to compound 10a (3 carbon linker, Ki: 111.70 nM) and 10b (5 carbon linker, Ki 167.19 nM).

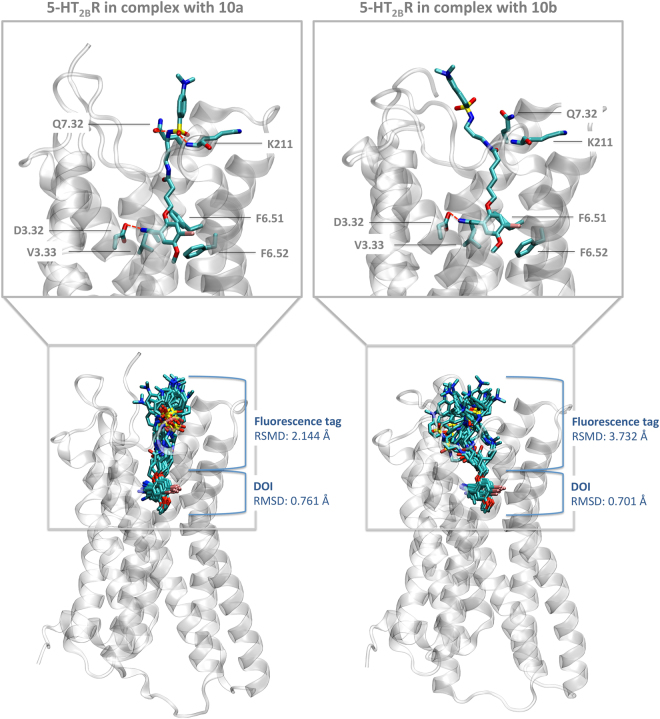

The propyl spacer group present in the most pharmacologically appealing fluorescent probe identified (10a) was fixed for subsequent fluorophore exploration. Accordingly, the carboxylic acid 7a was combined with a set of 9 propylamine-functionalized fluorescent tags (Fig. 4) by employing classical coupling experimental conditions (Fig. 4)44–48. The selection of fluorescent amines (8) embraced not only classical fluorescent tags (e.g., 8a,b or 8i) but also several new fluorescent scaffolds (e.g., 8c–h). The employed tags (8) incorporate fluorescent groups with relatively small to large molecular volumes, thus providing a collection of probes with diverse structural and photophysical properties. Some of the non-conventional fluorophores were chosen on the basis of their complementary absorption/emission fluorescence spectra, since they could be employed as donor and acceptor pairs for the implementation of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies in the near future. Amines 8d–8g were prepared from the corresponding dimethyl phenanthrene-9,10-dicarboxylates (or pentaphene-6,7-dicarboxylate, for 8g), these aromatic o-diesters were synthesized by palladium-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of arynes52, 53 with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (see supporting information). The experimental details for the syntheses of compounds 12 are outlined in Fig. 4. Briefly, the carboxylic acid 7a was reacted with different fluorescent amines (8a–i) employing DCC as a coupling reagent to give the amides 11. Finally, the protecting group (BOC) was removed by treatment with TFA to afford the fluorescent DOI-based probes 12a–i. Details on the synthesis, structural and photo-physical characterization of the obtained fluorescent probes are described in the experimental part and in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of the target fluorescent DOI analogues 12a–i and structures of the fluorescent amine precursors (8a–i). Reagents and conditions: (a) DCC, DCM, rt, 12 h (70–93%). (b) HCl/Dioxane, DCM, 0 °C, 2 h (50–78%).

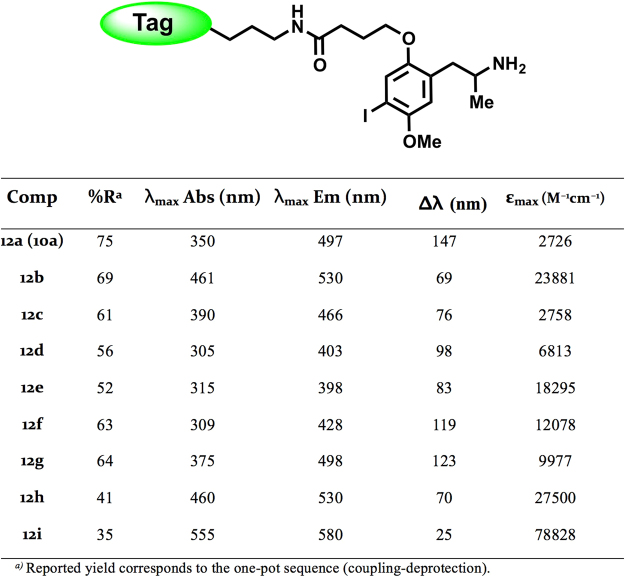

The absorption and emission spectra of the fluorescent 5-HT2 ligands (10 and 12) were determined on 10 μM solutions. The most relevant fluorescent properties are collected in Fig. 5. All of the synthesized derivatives emitted fluorescence in the visible region of the spectrum, with selected fluorescent tags (Fig. 4) providing distinctive properties and excitation wavelengths. The excitation wavelengths varied from 305 to 555 nm, whereas those for emission varied from 398 to 580 nm. Most of the compounds showed satisfactory Stokes shift values (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Photophysical properties of fluorescent DOI probes 12a–i.

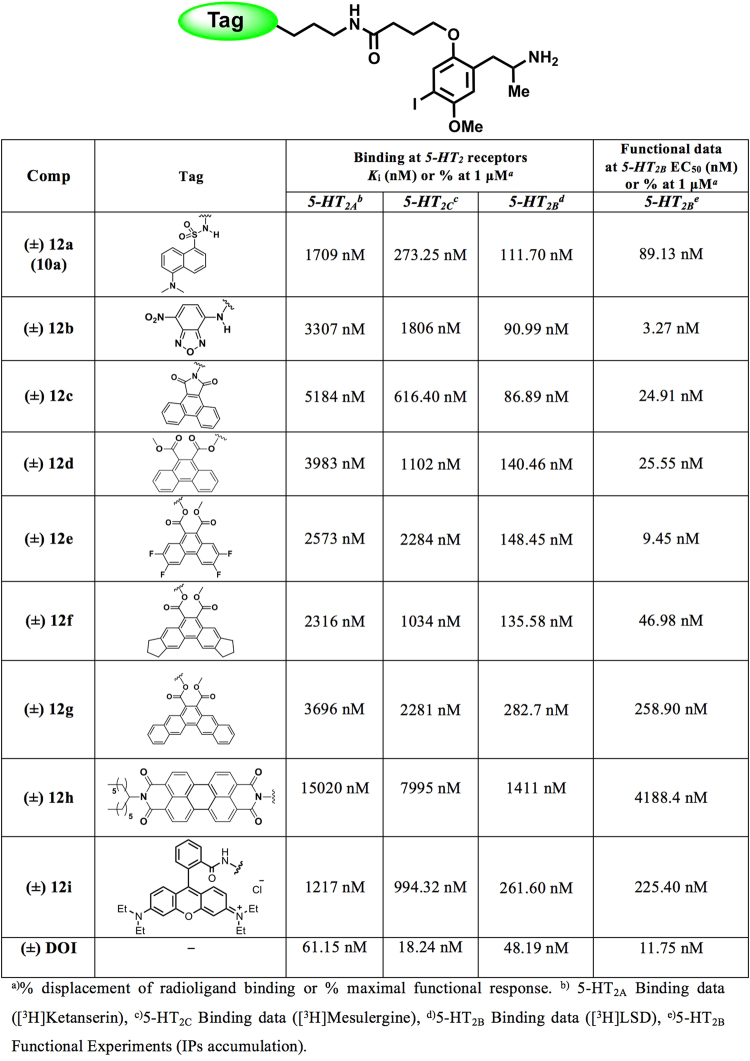

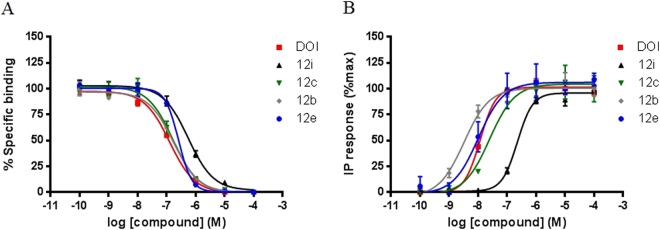

As for the first series described above, the pharmacological characterization of the resulting fluorescent ligands (12) was performed at two levels. Firstly, the in vitro affinity was assessed by radioligand binding assays at the three 5-HT2 receptor subtypes. Subsequently, the functional activity at the 5-HT2B receptors was evaluated (IPs accumulation). The data are collected in Fig. 6 and some of the representative curves obtained are shown in Fig. 7. It can be observed that all compounds stimulated IPs accumulation in a concentration-dependent manner, with EC50 values in the nanomolar range. These data confirm that the novel ligands retain the agonist behaviour exhibited by the model ligand (DOI).

Figure 6.

Structures and pharmacological data at 5-HT2 receptors for the DOI-based fluorescent probes 12a–i.

Figure 7.

Concentration-response curves obtained for representative ligands and DOI in binding experiments (A) and in functional studies (B).

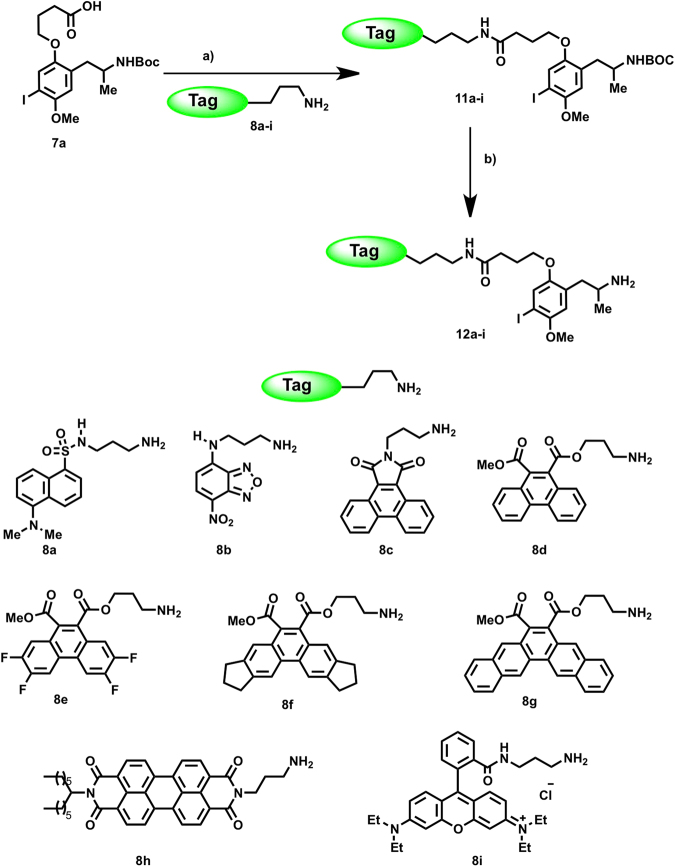

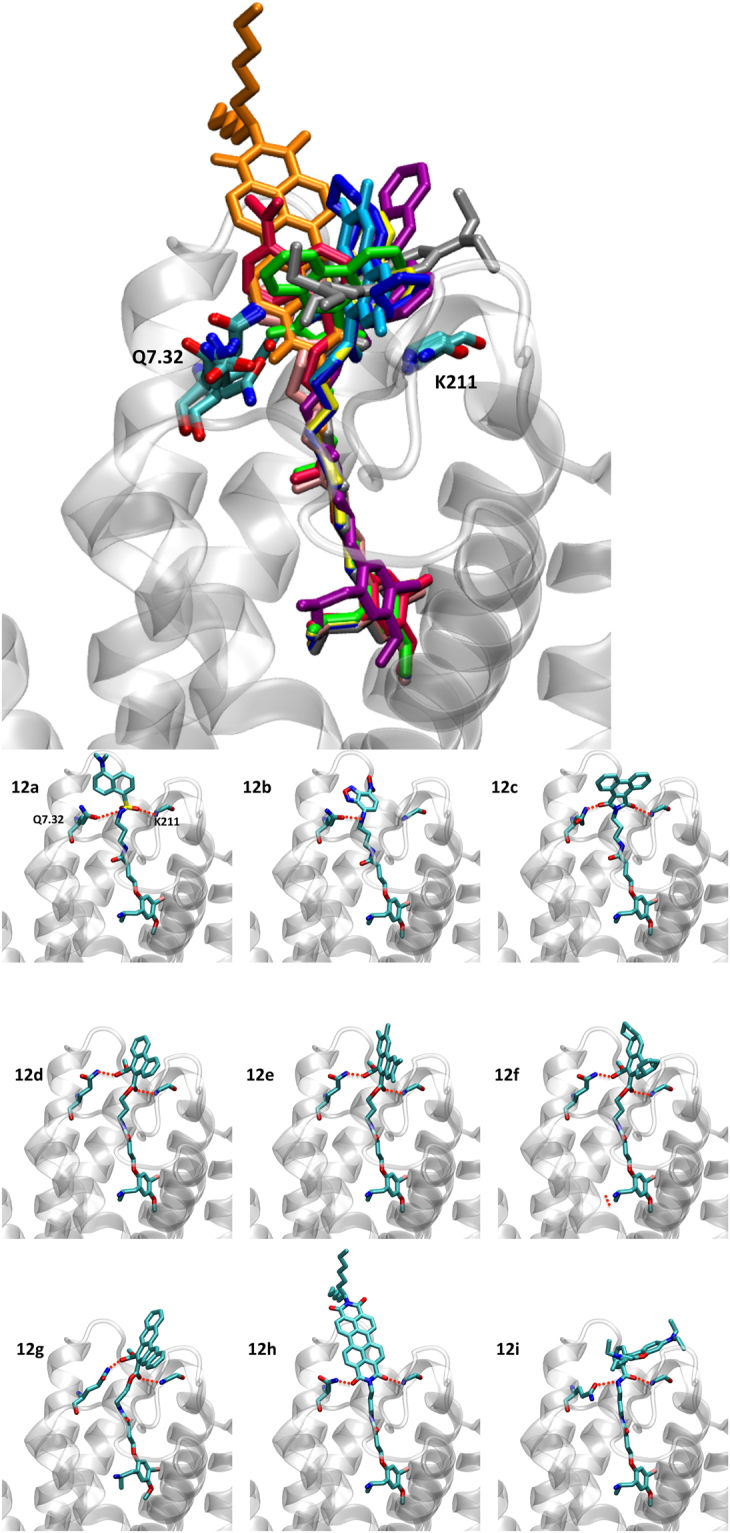

Examination of the pharmacological data contained in Fig. 6 reveals the identification of some highly attractive fluorescent ligands (e.g., 12b–f). Most of the fluorescent probes retain the incipient 5-HT2B selectivity profile observed for the former member of the series (10a). Taking advantage of the existing X-ray structure, we performed docking followed of molecular probes from the 12 series (12a to 12i) into the 5-HT2B receptor (PDB ID: 4IB4). All probes have overlapping docking poses (Figs 3 and 8) forming common interactions of the DOI fragment with residues D3.32, V3.33, F6.51 and F6.52 in the orthosteric binding pocket, as previously observed in our molecular dynamics simulations. In addition, we find that two residues, Q7.32 and the backbone of K211 at the extracellular loop clamp the polar part of the fluorophore tag (highlighted as red dashed lines in Fig. 8). The linker length determines the position of the fluorophore and its polar region with respect to the polar extracellular loop region. As discussed above, it is likely that longer linkers limit such favourable polar interaction. The obtained binding modes (Fig. 8) provide a potential explanation for affinity differences of studied compounds. According to our models, it appears that solvent exposure is an important factor for binding affinity towards the 5-HT2B receptor. Comparing dyes 12a to 12h (Fig. 8) suggests that increased and unfavourable exposure of complex and hydrophobic probes that reach out into the solvent seems to be responsible for a drop of 5-HT2B affinity.

Figure 8.

(A) Superimposition of docking poses of compounds 12a–i for the 5-HT2B receptor (PDB ID: 4IB4) with following color code: 12a - red, 12b - pink, 12c - green, 12d - yellow, 12e - cyan, 12f - dark blue, 12g - purple, 12h - orange and 12i - silver. (B) Individual docking poses for the probes 12a–i bound to the 5-HT2B receptor (PDB ID: 4IB4).

The obtained data support the benefits of introducing the acid-functionalized linker on the oxygen atom at position 2 of the phenyl ring of the model ligand (DOI), but also highlight the need for the optimized alkyl spacer (X = CH2−CH2−CH2). It should be noted that most of the fluorescent probes exhibited weak affinity (typically micromolar range) at the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors, while the functional experiments confirmed their agonistic behaviour (Fig. 7). Moreover, a progressive drop in 5-HT2B affinity was observed when the molecular complexity of the dye increased (e.g. cpds 12g–i). Of the probes obtained, the 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD) labelled DOI ligand (12b) warrants particular attention as it is slightly less potent (K i = 90.99 nM) than the reference ligand (DOI, K i = 48.19 nM) while exhibit an excellent selectivity (≥20-fold) for the 5-HT2B receptor subtype. Although the NBD ligand (12b) has the most attractive pharmacological profile, the rhodamine derivative 12i showed the most promising properties of the series from the photophysical point of view.

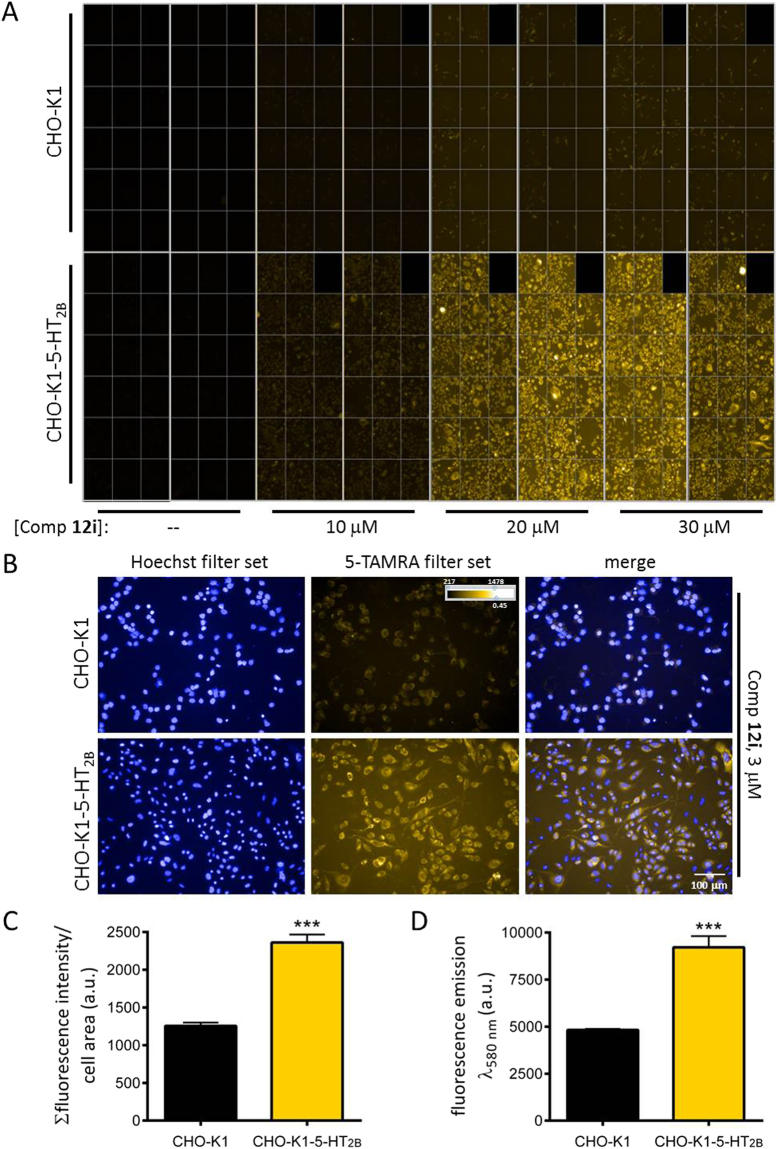

Having finished the preliminary photophysical and pharmacological characterization of the fluorescent derivatives 12a–i, their potential to specifically label 5-HT2B receptors in live cells was evaluated. Chinese hamster ovary K1 (CHO-K1) cells and CHO-K1 cells stably expressing the human serotonin 5-HT2B receptor (CHO-K1-5-HT2B), growing in 96-well plates, were incubated with at least three different concentrations of each compound for varying times and, after compound removal and washing of the cells, plates were subjected to fluorescence microscopy using a high content imaging instrument and the appropriate excitation and emission filter set for each compound.

Unfortunately, substantial specific labelling of 5-HT2B receptors was not observed for compounds 12a–h under any of the conditions evaluated. For these compounds, the cellular fluorescence intensities were similar in CHO-K1-5-HT2B and in parental untransfected control CHO-K1 cells (data not shown). This non-specific labelling of cells independently of 5-HT2B expression might arise due to non-specific membrane binding or membrane penetration of the fluorescent ligands, as observed previously for other fluorescent probes for GPCRs54.

While exhibiting a moderate 5-HT2B affinity/selectivity profiles compound 12i displayed a concentration-dependent specific labelling of CHO-K1-5-HT2B cells and this resulted in brighter fluorescence images obtained from these cells in comparison with those from control CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 9). The best results were obtained for a 3 μM concentration of compound 12i, which yielded the maximum window of specific labelling of the cells for the concentrations assayed (Fig. 9B). Under these conditions, the fluorescence intensity of the images collected from CHO-K1-5-HT2B cell wells was clearly superior to that observed for control CHO-K1 cell wells (***p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttests), as quantified both by automated image analysis and by direct measurement of fluorescence emission on a fluorescence plate reader (Fig. 9C,D). In the absence of compound, no substantial fluorescence signal was detected in the cells (Fig. 9A), which indicates a lack of signal specificity due to cell autofluorescence. These results support the specific binding of 12i to 5-HT2B receptors. Image acquisition at higher magnification (40x) and analysis retrieved similar quantitative results (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore, confocal microscopy imaging of CHO-K1-5-HT2B cells labelled with compound 12i in the same conditions also allowed visualization of the probe fluorescence, mainly located in intracellular compartments after 10 min incubation at 37 °C (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 9.

Labelling of 5-HT2B receptors by compound 12i in cells. (A) Living parental untransfected CHO-K1 cells (CHO-K1) and CHO-K1 cells stably expressing 5-HT2B receptors (CHO-K1-5-HT2B) were incubated in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of compound 12i and, after compound removal, fluorescence images (excitation wavelength 520–550 nm, emission wavelength 560–630 nm, standard filter set for 5-TAMRA) were acquired using an automated high content imaging instrument at 20x magnification. (B) Sample images from CHO-K1 and CHO-K1-5-HT2B cells labelled with 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (for nuclear staining) and compound 12i at a concentration of 3 μM, sampled from those quantified in (C,D). Minimum and maximum intensity and gamma correction of the images are shown in the colour scale in the panel. (C,D) Quantification of the fluorescence emission of compound 12i in images from CHO-K1 and CHO-K1-5-HT2B cells labelled with 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (for nuclear staining) and compound 12i at a concentration of 3 μM, both by image analysis (C) and by direct fluorescence measurement using a plate reader (D). The graphs show mean ± SEM of 4 wells, 5 fields/well (image analysis) and mean ± SEM of the same wells (plate reader). ***p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post tests.

The specificity and sensitivity of the 12i probe towards 5-HT2B receptors over other 5-HT2 receptor subtypes was evaluated by performing similar labelling experiments in CHO cells stably expressing 5-HT2A receptors (CHO-FA4-5-HT2A). In this case, no statistically significant specific labelling was detected when compound 12i was employed at the concentration of 3 μM (Supplementary Figure S3), and it was required to increase the 12i concentration to 20 μM in order to detect certain specific labelling of 5-HT2A receptors over background. However, even in these conditions (20 μM concentration of 12i) the signal window over background achieved for 5-HT2A labelling was considerably smaller than that detected in the case of 5-HT2B labelling at a concentration of 12i more than 6 times lower (3 μM) (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Figure S3). These results were in good agreement with the affinity values of compound 12i obtained from our radioligand binding assays. Hence, compound 12i allows direct visualization of 5-HT2B receptors stably expressed in a cell line by live fluorescence microscopy imaging and constitutes a promising molecular probe for future studies.

Conclusions

A set of fluorescent ligands based on the 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-propan-2-amine (DOI) chemotype has been developed. Some of the novel fluorescent probes (e.g. 12b) show excellent affinity and selectivity profiles at the 5-HT2B receptors, while retaining the agonistic functional behaviour of DOI. The study highlighted the most salient features of the structure-activity relationship in this series and these were supported by a molecular modelling study based on a receptor-driven docking model constructed on the basis of the crystal structure of the human 5-HT2B receptor. One of the fluorescent ligands reported here enabled the visualization of 5-HT2B receptors in live cells. Compound 12i specifically labelled 5-HT2B receptors stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner in fluorescence microscopy studies. Hence, the probes described here are the first examples of 5-HT2B selective fluorescent ligands and their availability should help to boost the GPCR biomolecular imaging field, thus enabling direct visualization and monitoring of spatiotemporal changes associated with 5-HT2B-related (patho)-physiological states. The ligand might be also useful for other assays where well characterized specific fluorescent probes and appropriate signal-to-background window are required, such as BRET-based binding assays.

Methods

Chemistry

Unless otherwise stated, all starting materials, reagents and solvents were purchased and used without further purification. The reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on 2.5 mm Merck silica gel GF 254 strips, and the purified compounds each showed a single spot; unless stated otherwise, UV light and/or iodine vapour were used to detect compounds. The purity and identity of all tested compounds were established by a combination of HPLC, elemental analysis, mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy as described below. Purification of isolated products was carried out by column chromatography (Kieselgel 0.040–0.063 mm, E. Merck) or medium pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) on a CombiFlash Companion (Teledyne ISCO) with RediSep pre-packed normal-phase silica gel (35–60 µm) columns followed by recrystallization. Melting points were determined on a Gallenkamp melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. The NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AM300 and XM500 spectrometers. Chemical shifts are given as δ values against tetramethylsilane as internal standard and J values are given in Hz. Mass spectra were obtained on a Varian MAT-711 instrument. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Autospec Micromass spectrometer. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1100 system using an Agilent Zorbax SB-Phenyl, 2.1 mm × 150 mm, 5 µm column with gradient elution using the mobile phases (A) H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH and (B) MeCN and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The purity of all tested compounds was determined to be >95%. The acid functionalized DOI precursors were synthesized by following previously described methods44–48. The experimental details of the synthesis of amines 8d–g are reported in the supplementary information.

General procedure for the synthesis of fluorescent amides 10 and 12

To a solution of the44–48 carboxylic acid (0.2 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (10 mL) at 0 °C was added N,N-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.25 mmol). To this mixture was slowly added the corresponding amine 8 (0.2 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After completion of the reaction, as indicated by TLC, the mixture was diluted with water and extracted with dichloromethane. The organic phase was dried (Na2SO4), filtered and concentrated to afford the corresponding amide (11), which was used in the next step. To a solution of the amide (11) in dichloromethane (10 mL) at 0 °C was slowly added 4N HCl in dioxane (3 mL) and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, as indicated by TLC, the mixture was neutralized with saturated sodium bicarbonate, diluted with water and extracted with dichloromethane. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to afford a residue that was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the target amide.

(±) 4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-((5-(dimethyl-amino)naphthalene)-1-sulfonamido)propyl)butanamide (10a, 12a)

Green-yellow wax; 75% (102 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.50 (dt, J = 8.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (dt, J = 8.7, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (dt, J = 7.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.43 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.08 (m, 2H), 6.79 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 3.85–3.71 (m, 6H), 3.29–3.11 (m, 3H), 2.99–2.74 (m, 9H), 2.60 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.42–2.19 (m, 2H), 1.98 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.51 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 1.07 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.2, 152.4, 151.9, 151.6, 135.2, 130.2, 129.8, 129.6, 129.3, 129.1, 128.3, 123.2, 122.6, 118.9, 115.2, 113.9, 82.8, 67.6, 57.1, 47.3, 45.4, 40.5, 40.1, 35.9, 32.8, 29.6, 25.3, 23.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C29H40IN4O5S [M + H]+: 683.1759, found: 683.1760.

(±) 7-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-((5-(dimethylami-no)naphthalene)-1-sulfonamido)propyl)heptanamide (10b)

Green-yellow wax, 71% (103 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.48 (dt, J = 8.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (dt, J = 8.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (dt, J = 7.3, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.22–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.88 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (s, 1H), 3.92–3.77 (m, 3H), 3.75–3.69 (m, 3H), 3.28–3.12 (m, 3H), 2.97–2.88 (m, 3H), 2.87–2.78 (m, 6H), 2.24–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.50 (m, 6H), 1.48–1.20 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 174.7, 156.1, 151.9, 144.6, 134.2, 133.6, 129.8, 129.7, 129.0, 128.9, 127.5, 124.5, 123.8, 122.3, 119.5, 114.7, 86.5, 68.7, 57.6, 46.2, 44.8, 40.0, 39.5, 38.6, 37.9, 29.7, 29.2, 28.6, 27.1, 26.2, 22.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C32H46IN4O5S [M + H]+: 725.2228, found: 725.2216.

(±) 11-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-((5-(dimethyl-amino)naphthalene)-1-sulfonamido)propyl)undecanamide (10c)

Green-yellow solid; mp: 171–173 °C, 63% (98 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.51 (dt, J = 8.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (dt, J = 8.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (dt, J = 7.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.67 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.03 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.94–3.82 (m, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.41–3.30 (m, 1H), 3.24 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.99–2.75 (m, 9H), 2.73–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.09 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.72 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.63–1.46 (m, 4H), 1.46–1.07 (m, 17H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 174.0, 152.3, 151.8, 135.3, 130.2, 129.8, 129.6, 129.0, 128.3, 128.1, 123.1, 122.5, 119.0, 115.2, 114.3, 83.1, 68.7, 57.1, 47.4, 45.4, 45.4, 39.9, 39.5, 36.5, 35.9, 29.6, 29.3, 29.1, 29.0, 29.0, 29.0, 26.0, 25.5, 21.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C36H54IN4O5S [M + H]+: 781.2854, found: 781.2851.

(±) 3-(2-(2-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(3-((5-(dimethylamino)naphthalene)-1-sulfonamido)propyl)propanamide (10d)

Green-yellow solid; mp: 107–109 °C, 57% (86 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.53 (dt, J = 8.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.11 (m, 2H), 6.83 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 3.88 (td, J = 6.0, 2.9 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.55 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.51–3.34 (m, 9H), 3.09 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 2.88 (s, 6H), 2.59 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (td, J = 7.2, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (p, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.07 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.6, 152.5, 151.8, 151.4, 134.8, 130.4, 129.8, 129.6, 129.2, 128.4, 125.9, 123.2, 122.5, 119.0, 115.3, 114.3, 83.9, 70.0, 69.9, 69.9, 69.3, 68.3, 57.1, 48.2, 45.4, 42.8, 39.2, 36.2, 33.2, 25.3, 18.1. HRMS (CI) m/z: calcd. for C32H46IN4O7S [M + H]+: 757.2132, found: 757.2161.

(±) 4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-((7-nitroben-zo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazol-4-yl)amino)propyl)butanamide (12b)

Orange solid; mp: 158–160 °C; 69% (84 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.30 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.51 (s, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (dt, J = 6.3, 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.40 (dq, J = 8.6, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.28–3.16 (m, 3H), 2.90 (dd, J = 13.1, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.57 (dd, J = 13.1, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 2.38–2.26 (m, 2H), 2.01–1.89 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.19–0.94 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3 + MeOD) δ (ppm): 174.5, 152.4, 151.3, 144.2, 137.2, 125.6, 122.3, 114.1, 98.4, 83.9, 67.9, 56.8, 41.0, 36.6, 36.5, 36.0, 32.9, 32.9, 29.4, 27.6, 25.3, 17.9. HRMS (CI) m/z: calcd. for C23H30IN6O6 [M + H]+: 613.1272, found: 613.1270.

(±) 4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-(1,3-dioxo-1,3-dihydro-2H-dibenzo[e,g]isoindol-2-yl)propyl)butanamide (12c)

Pale-yellow wax; 61% (83 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 9.21–8.94 (m, 2H), 8.72 (ddd, J = 8.7, 1.3, 0.8 Hz, 2H), 7.93–7.62 (m, 4H), 7.21 (q, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.81–6.56 (m, 2H), 4.05–3.84 (m, 3H), 3.77 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 3H), 3.42–3.18 (m, 3H), 2.77–2.54 (m, 3H), 2.51–2.41 (m, 2H), 1.93 (dt, J = 13.0, 6.4 Hz, 4H), 1.18 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 174.0, 171.9, 171.8, 155.1, 153.9, 132.2, 131.0, 128.6, 127.4, 127.3, 126.6, 125.4, 123.6, 123.1, 115.2, 86.3, 68.9, 58.2, 49.3, 40.4, 39.9, 37.4, 32.9, 26.9, 24.9, 22.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C33H35IN3O5 [M + H]+: 680.1616, found: 680.1606.

(±) 9-(3-(4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)butanamido)pro-pyl)-10-methyl phenanthrene-9,10-dicarboxylate (12d)

Pale-yellow wax; 56% (79 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.84 (dt, J = 7.3, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.92 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (td, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (tt, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 4.22 (td, J = 12.2, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 4.04–3.86 (m, 5H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.60–3.42 (m, 3H), 3.00 (dd, J = 12.4, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.54 (dd, J = 12.6, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.35–2.23 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.92 (m, 2H), 1.90–1.80 (m, 2H), 1.70 (s, 2H), 1.05 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.7, 168.9, 168.1, 152.4, 151.2, 130.9, 129.8, 129.4, 128.6, 127.7, 127.7, 127.4, 126.7, 126.5, 125.8, 122.9, 122.4, 122.3, 114.1, 83.8, 67.8, 64.3, 56.9, 52.8, 36.6, 32.9, 29.5, 28.1, 25.2, 22.5, 18.4. HRMS (CI) m/z: calcd. for C34H38IN2O7 [M + H]+: 713.1724, found: 713.1739.

(±) 9-(3-(4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)butanamido)pro-pyl) 10-methyl 2,3,6,7-tetrafluorophenanthrene-9,10-dicarboxylate (12e)

Pale-yellow wax; 52% (82 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.54–8.43 (m, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 4.16 (td, J = 12.4, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.91–3.88 (m, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.76 (td, J = 12.2, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 3.39–3.32 (m, 1H), 3.01 (dd, J = 12.1, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.68 (dd, J = 12.3, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 2.60–2.55 (m, 2H), 2.15–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.78–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.65 (s, 2H), 1.17 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 174.6, 168.4, 167.8, 157.3, 154.8, 152.4, 151.7, 149.6, 148.7, 129.6, 128.3, 127.3, 127.0, 126.9, 125.6, 124.3, 123.9, 115.6, 114.4, 113.8, 86.5, 68.3, 63.6, 58.1, 52.3, 47.5, 39.8, 36.9, 32.3, 28.6, 24.3, 22.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C34H34F4IN2O7 [M + H]+: 785.1341, found: 785.1341.

(±) 5-(3-(4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)butanamido)pro-pyl)-6-methyl-1,2,3,8,9,10-hexahydrodicyclopenta[b,h]phenanthrene-5,6-dicarbo-xylate (12f)

Pale-yellow wax; 63% (99 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.61–8.44 (m, 2H), 7.96–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.22–7.01 (m, 1H), 6.71–6.46 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (s, 3H), 3.90 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.83–3.58 (m, 5H), 3.45–3.29 (m, 1H), 3.24–2.99 (m, 11H), 2.97–2.81 (m, 2H), 2.56–2.44 (m, 2H), 2.39–1.79 (m, 8H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.9, 169.6, 168.7, 152.4, 151.4, 146.0, 145.8, 144.6, 144.4, 130.2, 127.5, 125.8, 125.6, 122.6, 122.3, 121.2, 121.1, 117.7, 114.2, 114.0, 83.3, 67.7, 63.6, 57.0, 52.6, 47.5, 38.6, 36.8, 33.2, 32.8, 31.6, 30.6, 28.3, 25.9, 24.7, 22.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C40H46IN2O7 [M + H]+: 793.2344, found: 793.2347.

(±) 6-(3-(4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)butanamido)pro-pyl) 7-methyl pentaphene-6,7-dicarboxylate (12g)

Pale-yellow solid; mp: 150–152 °C; 64% (104 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 9.15 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 2H), 8.46 (d, J = 24.9 Hz, 2H), 8.26–7.85 (m, 4H), 7.79–7.32 (m, 5H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 6.30 (s, 1H), 4.56 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 4.06 (s, 3H), 3.80–3.28 (m, 8H), 3.14–2.83 (m, 1H), 2.61–2.45 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.14–1.81 (m, 4H), 1.30–1.10 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.5, 168.9, 168.1, 152.3, 151.0, 132.7, 132.6, 132.1, 130.6, 130.3, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 128.1, 127.4, 126.7, 126.5, 125.5, 124.8, 124.7, 122.4, 122.3, 122.1, 113.8, 83.9, 68.0, 64.7, 56.8, 53.1, 48.2, 36.7, 36.2, 33.4, 28.3, 25.3, 18.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C42H42IN2O7 [M + H]+: 813.2031, found: 813.2036.

(±) 4-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-N-(3-(1,3,8,10-tetraoxo-9-(tridecan-7-yl)-3,8,9,10-tetrahydroanthra[2,1,9-def:6,5,10-d′e′f′]diisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)propyl)butanamide (12h)

Red solid, mp: 169–171 °C; 41% (82 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.44 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 8.18 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 8.12–8.05 (m, 4H), 7.48 (brs, 1H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 5.15 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.01 – 3.80 (m, 4H), 3.78–3.71 (m, 1H), 3.65–3.52 (m, 5H), 3.36–3.23 (m, 2H), 3.12–3.04 (m, 1H), 2.93–2.84 (m, 1H), 2.55 (brs, 2H), 2.29–2.09 (m, 3H), 2.05–1.89 (m, 4H), 1.50–1.06 (m, 19H), 0.85 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 175.5, 162.8, 162.7, 162.6, 162.6, 155.8, 154.1, 139.5, 139.1, 132.4, 131.8, 131.1, 127.5, 127.5, 126.8, 126.8, 124.9, 124.9, 124.6, 124.5, 124.4, 124.4, 124.4, 124.3, 124.3, 123.8, 123.8, 123.8, 123.8, 115.8, 87.3, 69.9, 57.1, 54.6, 48.4, 40.5, 38.9, 37.6, 35.7, 34.8, 34.8, 31.7, 31.7, 29.4, 29.4, 26.8, 26.6, 26.6, 25.7, 23.4 22.9, 22.9, 14.1, 14.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C54H62IN4O7 [M + H]+: 1005.3657, found: 1005.3659.

(±) N-(9-(2-((26-(2-(2-aminopropyl)-5-iodo-4-methoxyphenoxy)-3,7,23-trioxo-12,15,18-trioxa-4,8,22-triazahexacosyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-6-(diethylamino)-3H-xanthen-3-ylidene)-N-ethylethanaminium (12i)

Dark red solid, mp: 151–153 °C, 35% (84 mg); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.70–7.55 (m, 3H), 7.36–7.11 (m, 6H), 6.79–6.60 (m, 3H), 4.25–4.00 (m, 5H), 3.98–3.86 (m, 3H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.69–3.46 (m, 17H), 3.46–3.26 (m, 6H), 3.16–2.88 (m, 7H), 2.85–2.68 (m, 5H), 2.64–2.37 (m, 2H), 2.21–1.97 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.10 (m, 15H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.7, 173.4, 169.4, 169.0, 157.9, 157.8, 155.6, 152.4, 151.6, 136.1, 132.4, 132.2, 130.2, 129.7, 129.3, 128.1, 126.8, 122.2, 114.5, 113.9, 113.8, 113.7, 96.1, 83.6, 69.8, 69.5, 67.9, 63.1, 57.2, 52.9, 51.8, 51.7, 51.3, 50.5, 47.8, 46.0, 44.3, 39.2, 39.1, 38.7, 37.2, 35.3, 34.4, 30.6, 29.6, 24.9, 24.3, 17.8, 12.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for [C57H78IN8O10]+ [M]+: 1162.5080, found: 1162.5085.

Biological methods

Cell Culture

Chinese hamster ovary K1 (CHO-K1) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-F12 (DMEM/F12) (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Spain) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma Aldrich, Spain), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma Aldrich, Spain) and 100 U/mL penicillin/0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich, Spain). CHO cells stably expressing 5-HT2A receptors (CHO-FA4-5-HT2A) were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 100 U/mL penicillin/0.1 mg/mL streptomycin and 300 μg/mL hygromycin (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Spain). CHO-K1 cells stably expressing the human 5-HT2B receptor (CHO-K1-5-HT2B) were maintained in Advanced DMEM/F-12 (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Spain) supplemented with 1% FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 10 U/mL penicillin/0.01 mg/mL streptomycin and 0.4 mg/mL geneticin (G-418) (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Spain).

Radioligand competition binding assays at human 5-HT2A receptors

Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor competition binding experiments were carried out in membranes from CHO-FA4-5-HT2A cells prepared in our group. On the day of the assay, membranes were defrosted and resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Each reaction well of a 96-well plate contained 80 μg of protein, 1 nM [3H]Ketanserin (50.3 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and different concentrations of the compounds in the range from 0.01 nM to 10 µM. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM methysergide (Sigma Aldrich, Spain). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, after which samples were transferred to multiscreen GF/B 96-well plates (Millipore, Spain) pretreated with 0.5% polyethylenimine (PEI, Sigma Aldrich, Spain), filtered, and washed six times with 250 μL wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.6). The filters were dried, 35 μL Universol (MP Biomedicals, Spain) per well were added and radioactivity was detected in a microplate beta scintillation counter (Microbeta Trilux, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Radioligand competition binding assays at human 5-HT2B receptors

Serotonin 5-HT2B receptor competition binding experiments were carried out in membranes from CHO-K1-5-HT2B cells prepared in our group. On the day of the assay, membranes were defrosted and resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 4 mM CaCl2, 0.1% ascorbic acid, pH 7.4). Each reaction well of a 96-well plate contained 5 μg of protein, 1 nM [3H]LSD (83.6 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and different concentrations of the compounds in the range from 0.01 nM to 10 µM. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 50 μM serotonin (Sigma Aldrich, Spain). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, after which samples were transferred to multiscreen GF/C 96-well plates (Millipore, Spain) pretreated with 0.5% polyethylenimine (PEI, Sigma Aldrich, Spain), filtered, and washed four times with 250 μL wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). The filters were dried, 35 μL Universol (MP Biomedicals, Spain) per well were added and radioactivity was measured as described above.

Radioligand competition binding assays at human 5-HT2C receptors

Serotonin 5-HT2C receptor competition binding experiments were carried out in membranes from HeLa-5-HT2C cells prepared in our group. On the day of assay, membranes were defrosted and resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Each reaction well of a 96-well plate contained 15 μg of protein, 4 nM [3H]Mesulergine (83.5 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and different concentrations of the compounds in the range from 0.01 nM to 10µM. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM mianserin (Sigma Aldrich, Spain). The reaction mixture was incubated at 27 °C for 1 h, after which samples were transferred to multiscreen GF/C 96-well plates (Millipore, Spain) pretreated with 0.5% polyethylenimine (PEI, Sigma Aldrich, Spain), filtered, and washed four times with 250 μL wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.6). The filters were dried, 35 μL Universol (MP Biomedicals, Spain) per well were added and radioactivity was measured as described above.

Functional Assays of IPs accumulation at human 5-HT2B receptors

CHO-K1 cells stably expressing human 5-HT2B receptor (CHO-K1-5-HT2B) cells were seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 20000 cells/well. After 24 h, growth medium was replaced by serum-free medium containing 10 μCi/mL [3H]myo-inositol (20.3 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer) for 24 h. After a labelling period of 24 h, cells were washed for 10 min at 37 °C with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, 20 mM LiCl and 2% fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (BSA) (assay buffer) and incubated in assay buffer in the absence (vehicle) or in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the compounds for 20 min at 37 °C. After the incubation time, assay buffer was discarded and 200 μL of 100 mM formic acid was added to the cells for 30 min at 4 °C and 20 μL of the lysate were transferred to a flexiplate plate (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) together with 80 μL of a solution of RNA Binding YSi SPA Beads (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) to measure accumulation of [3H]IPs (IP1,IP2, and IP3, collectively referred to as IPs). Radioactivity was quantified in a liquid scintillation counter WALLAC Microbeta TriLux 1450-023.

Data analysis of radioligand and functional assays

Concentration-response curves were fitted using Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software). A nonlinear regression fitting to a four parameter logistic equation and the Cheng–Prusoff equation were used to calculate EC50 values and K i, respectively.

Fluorescence microscopy imaging

For cell labelling studies, cells were plated onto 96-well plates (Cell Carrier; Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) pre-treated with poly-D-lysine hydrobromide 0.1 mg/mL (Sigma Aldrich, Spain) at a density of 10000 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. For cell labelling with compound 12i, cultured media was removed and cells were washed with HBSS supplemented with 0.1% BSA and incubated in the same buffer for 30 min at 37 °C. The buffer was removed and cells were incubated in the absence or presence of the compound at the indicated concentrations in HBSS for 10 min at 37 °C. A 10−2 M stock solution of the compound was prepared in DMSO and then diluted to the final assay concentration in HBSS. Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/mL) (Thermo Fisher, Spain) was used to stain nuclei where indicated. After the incubation time, the supernatant was removed, cells were washed twice with HBSS and plates were subjected to microscopy. Fluorescence images were acquired using an Operetta high content imaging instrument (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 20x and 40x magnification, at excitation wavelengths of 520–550 nm and emission wavelengths of 560–630 nm (standard 5-TAMRA filter set) for compound 12i, and excitation wavelengths of 360–400 nm and emission wavelengths of 410–480 nm for Hoechst 33342 (standard Hoechst 33342 filter set).

Quantification of fluorescence intensity

The fluorescence intensity of the cells labelled with compound 12i was quantified by image analysis of the acquired images using Harmony v3.5 software (Perkin-Elmer). Object identification was performed in the Hoechst channel followed by intensity measurement of the cell area of the objects in the 5-TAMRA channel and the results are expressed as the sum of the 5-TAMRA intensity in the cell region divided by the sum of cell area in each well. Five fields of view/well and 4 wells/condition were analyzed. Fluorescence intensity of the labeled cells was also quantified in the same plates and wells by measuring fluorescence emission (excitation wavelength 550 nm, emission wavelength 580 nm) on an Infinite M1000Pro fluorescence plate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). Data (mean ± SEM) obtained from both quantification methods were represented as bar graphs using Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software).

In Silico Methods

Receptor preparation from the X-ray crystal structure

To simulate the interactions of 5-HT2B with fluorescent probes, we used the recently crystallized structure of the receptor (PDB ID: 4IB4)55. The area of the structure, corresponding to the BRIL protein, was cut out. The protonation states were calculated at pH 7.4 using PROPKA56 software implemented in MOE (http://www.chemcomp.com/software.htm).

Ligand Docking

First, DOI was docked into the 5-HT2B receptor defining a centroid point in the residue Asp3.32 and expanding it to 20 Å around this residue using the GOLD software57. One hundred genetic algorithm runs were submitted and further scored employing the ASP scoring function. The ligands were restricted to form a salt bridge between their positively charged nitrogen and the carboxylate of Asp3.32. The best poses from this docking procedure were used as inputs to explore the conformational space of the ligands with the Low Mode Search function of MOE, which is a short MD simulation that uses velocities with little kinetic energy on the high-frequency vibrational modes, using the AMBER12:EHT force field, Born solvation, 300 K and default settings. The lowest energetic pose was then used as a starting point to link the dansyl probe using MOE. In order to explore stability and the conformational space, we carried out extended molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the 5-HT2B receptor in complex with DOI-linked fluorescence probes.

Extended MD simulations

The protein with the ligand docked was then embedded in a 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine bilayer using Charmm-gui58. Information obtained from the OPM database was employed to ensure proper alignment of the protein in membrane59. The system was solvated with TIP3 water. The ionic strength of the system was set to 0.15 M using NaCl ions. Parameters were derived from the Charmm36 forcefield. Missing parameters for the ligands were obtained from CGenFF60. Simulations were carried out in ACEMD61 and the hydrogen mass-repartitioning scheme employed in ACEMD allowed us to use a 4 fs timestep62. The system was minimized for 3000 steps, and then subjected to 2 ns of NPT equilibration at a constant pressure of 1.01325 bar to ensure proper lipid packing in the membrane. Afterwards we proceeded with NVT simulations at a temperature of 300 K. For each complex (complex 1: 10a-5-HT2B and complex 2: 10b-5-HT2B) we generated 4 individually built starting structures and simulated them for 200 ns each, yielding a total time of 800 ns per complex.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out within the framework of the Cost Action GLISTEN and financially supported by the Spanish Government (grant numbers SAF2009-13609-C04-03 and GPC2014/003 (PS09/63) to E.S. and SAF2014-57138-C2-1-R to M.C. and M.I.L.). Authors also thanks financial support from Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria of the Galician Government: (grant: GPC2014/03), Centro Singular de Investigación de Galicia accreditation 2016-2019 (ED431G/09). J. S. acknowledges financial support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER (CP12/03139 and PI15/00460).

Author Contributions

E.S. and M.I.L. conceived and designed the study. Supervision: E.S., J.S., M.C. Synthesis: J.A., P.L., J.M.P.-R., D.P., D.G., X.G.-M. Binding experiments: A.I., J.M.B. Docking experiments: T.M.S. and J.S. Labelling experiments: R.A.F., M.C. Writing: E.S., J.A., A.I., M.C. All authors read and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11370-2

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009;60:355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyer D, et al. International union of pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:157–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerhardt CC, van Heerikhuizen H. Functional characteristics of heterologously expressed 5-HT receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;334:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth BL, Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:353–359. doi: 10.1038/nrd1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCorvy JD, Roth BL. Structure and function of serotonin G protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;150:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols DE, Nichols CD. Serotonin receptors. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1614–1641. doi: 10.1021/cr078224o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, et al. Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science. 2013;340:610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1232807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth BL, Willins DL, Kristiansen K, Kroeze WK. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2-family receptors (5-hydroxytryptamine 2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine 2B, 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2C): where structure meets function. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998;79:231–257. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(98)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leysen JE. 5HT2 Receptors. Curr. Drug Targets, CNS Neurol. Disord. 2004;3:11–26. doi: 10.2174/1568007043482598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth BL, Hanizavareh SM, Blum AE. Serotonin receptors represent highly favorable molecular targets for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia and other disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2004;174:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1683-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroeze WK, Kristiansen K, Roth BL. Molecular biology of serotonin receptors structure and function at the molecular level. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:507–528. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall, F. S. Serotonin: Biosynthesis, Regulation and Health Implications, 333–360 (Nova Science Publishers, 2013).

- 13.Nelson DL. The serotonin 5HT2B subfamily of receptors: Pharmacological challenges. Med. Chem. Res. 1993;3:306–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KW, Phebus LA, Cohen ML. Serotonin in migraine: theories, animal models and emerging therapies. Prog. Drug Res. 1998;51:219–244. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8845-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Launay JM, Scheneider B, Loric S, De Prada M, Kellermann O. Serotonin transport and serotonin transporter-mediated antidepressant recognition are controlled by 5-HT2B receptor signaling in serotonergic neuronal cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:1843–1854. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5724com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doly S, et al. Role of serotonin via 5-HT2B receptors in the reinforcing effects of MDMA in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nebigil CG, et al. Serotonin 2B is required for heart development. PNAS. 2000;97:9508–9513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nebigil CG, Etienne N, Messaddeq N, Maroteaux L. Serotonin is a novel survival factor of cardiomyocytes: mitochondria as a target of 5-HT2B receptor signaling. FASEB J. 2003;17:1373–1375. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1122fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth BL. Drugs and valvular heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:6–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elangbam CS, et al. 5-Hydroxytriptamine (5-HT)-induced valvulopathy: compositional valvular alterations are associated with 5HT2B receptor and 5-HT transporter transcript changes in Sprague-Dawley rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008;60:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Serotonergic drugs and valvular heart disease. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2009;8:317–329. doi: 10.1517/14740330902931524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elangbam CS. Drug-induced valvulopathy: an update. Toxicologic Pathology. 2010;38:837–848. doi: 10.1177/0192623310378027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman RB, et al. Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT2B receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications. Circulation. 2000;102:2836–2841. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.23.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setola V, Dukat M, Glennon RA, Roth BL. Molecular determinants for the interaction of the valvulopathic anorexigen norfenfluramine with the 5-HT2B receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:20–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald LW, et al. Possible role of valvular serotonin 5-HT2B receptors in the cardiopathy associated with fenfluramine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrejak M, Tribouilloy C. Drug-induced valvular heart disease: An update. Archives of Cardiovascular Disease. 2013;106(106):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanettini R, et al. Valvular heart disease and the use of dopamine agonists for Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356(356):39–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brea J, et al. Emerging opportunities and concerns for drug discovery at serotonin 5-HT2B receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:493–503. doi: 10.2174/156802610791111524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann DA, Oakley F. Serotonin paracrine signaling in tissue fibrosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2013;1832:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312:217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavis LD, Raines RT. Bright ideas for chemical biology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:142–155. doi: 10.1021/cb700248m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma Z, Du L, Li M. Toward fluorescent probes for G‐protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) J. Med. Chem. 2004;57:8187–8203. doi: 10.1021/jm401823z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alonso D, et al. Development of fluorescent ligands for the human 5-HT1A receptor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:249–253. doi: 10.1021/ml100053y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonin J, et al. High-affinity fluorescent probes for the 5-HT3 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1151–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vázquez-Villa H, et al. Development of molecular probes for the human 5-HT6 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:7095–7106. doi: 10.1021/jm1007177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glennon RA, McKenney JD, Lyon RA, Titelert M. 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 binding characteristics of 1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromopheny1)-2-aminopropane analogues. J. Med. Chem. 1986;29:194–199. doi: 10.1021/jm00152a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glennon RA, Titeler M, McKenney JD. Evidence for 5-HT2 involvement in the mechanism of action of hallucinogenic agents. Life Sci. 1994;35:2505–2511. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glennon RA, et al. [125I]-1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-amino-propane: an iodinated radioligand that specifically labels the agonist high-affinity state of 5-HT2 serotonin receptors. J. Med. Chem. 1988;31:7–11. doi: 10.1021/jm00396a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canal CE, Morgan D. Head-twitch response in rodents induced by the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine: a comprehensive history, a re-evaluation of mechanisms, and its utility as a model. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4:556–576. doi: 10.1002/dta.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathis CA, Hoffman AJ, Nichols DE, Shulgin AT. Synthesis of high specific activity 125I- and 123I-labelled enantiomers of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenylisopropylamine (DOI) Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2006;25:1255–1265. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.2580251112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu B, et al. Serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor activation suppresses tumor necrosis factor-α-induced inflammation with extraordinary potency. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 2008;327:316–323. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nau F, Yu B, Martin D, Nichols CD. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation blocks TNF-α-mediated inflammation in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho, A. K. & Segal, D. S Amphetamine and its Analogs: Psychopharmacology, Toxicology and Abuse 3–21 (Academic Press, 1994).

- 44.Hathaway BA, Taylor BE, Wittenborn JS. Selective preparation of 4-(bromo or iodo)-2,5-dimethoxybenzonitrile and 2-(bromo or iodo)-3,6-dimethoxybenzo-nitrile from 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde. Synth. Commun. 1998;28:4628–4637. doi: 10.1080/00397919808004528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomlinson ID, Grey JL, Rosenthal SJ. A synthesis of 6-(2,5-dimethoxypropyl)phenyl)-hexyltiol. A ligand for conjugation with fluorescent cadmium selenide/zinc sulfide core/shell nanocrystals and biological imaging. Molecules. 2002;7:777–790. doi: 10.3390/71100777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cloonan SM, et al. Synthesis and serotonin transporter activity of sulphur-substituted α-alkyl phenethylamines as a new class of anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000;44:4862–4888. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheehan JC, Hess GP. A new method of forming peptide bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;77:1067–1068. doi: 10.1021/ja01609a099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han G, Tamaki M, Hruby VJ. Fast, efficient and selective deprotection of tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group using HCl/dioxane. J. Peptide Res. 2001;58:338–341. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2001.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brea J, et al. P. QF2004B, a potential antipsychotic butyrophenone derivative with similar pharmacological properties to clozapine. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:251–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodríguez D, Brea J, Loza MI, Carlsson J. Structure-based discovery of selective serotonin 5-HT(1B) receptor ligands. Structure. 2014;22:1140–51. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martí-Solano M, et al. Detection of new biased agonists for the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor: modeling and experimental validation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015;87:740–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.097022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peña D, Pérez D, Guitián E, Castedo L. Palladium-catalyzed cocyclization of arynes with alkynes: selective synthesis of phenanthrenes and naphthalenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:5827–5828. doi: 10.1021/ja9907111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peña D, Pérez D, Guitián E, Castedo L. Selective palladium-catalyzed cocyclotrimerization of arynes with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate: a versatile method for the synthesis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:6944–6950. doi: 10.1021/jo000535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vernall AJ, et al. Conversion of a non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist into A3-selective high affinity fluorescent probes using peptide-based linkers. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:5673–82. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41221k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wacker D, et al. Structural features for functional selectivity at serotonin receptors. Science. 2013;340:615–619. doi: 10.1126/science.1232808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H, Robertson AD, Jensen JH. Very fast empirical prediction and rationalization of protein pKa values. Proteins Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2005;61:704–721. doi: 10.1002/prot.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verdonk ML, Cole JC, Hartshorn MJ, Murray CW, Taylor RD. Improved protein-ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins. 2003;52:609–623. doi: 10.1002/prot.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM‐GUI: a web‐based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lomize MA, Lomize AL, Pogozheva ID, Mosberg HI. OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:623–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanommeslaeghe K, et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug‐like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all‐atom additive biological force fields. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harvey MJ, Giupponi G, Fabritiis GD. ACEMD: accelerating biomolecular dynamics in the microsecond time scale. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2009;5:1632–1639. doi: 10.1021/ct9000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feenstra KA, Hess B, Berendsen HJ. Improving efficiency of large timescale molecular dynamics simulations of hydrogen-rich systems. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:786–798. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199906)20:8<786::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.