Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of differential concentration of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) on the morphology, cell viability, mRNA, and protein expression of stem cells obtained from the intraoral area. Stem cells derived obtained from gingiva were cultured in a growth medium in the presence of DMSO at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 10%. The morphology and cellular viability were evaluated on days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to evaluate the mRNA levels of collagen I and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2). Immunofluorescent assays were performed for Runx2 and collagen I, and protein expressions were measured, including those of Runx2 and collagen I using western blot analysis. Cells in the control group showed normal fibroblast morphology in the growth media. Cells from the higher DMSO concentration were significantly different compared to the control. The decrease in cell viability was noted in the higher concentration. A notable change in collagen I expression was noted at the higher concentrations of DMSO groups. Based on these findings, it was concluded that DMSO may have detrimental effects on the cell morphology and viability of mesenchymal stem cells. The results also suggest that DMSO has toxic effects via reduced collagen I expression.

Keywords: cell shape, cell survival, dimethylsulphoxide, oral medicine, stem cells

Introduction

Dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) is an organosulfur compound, with the chemical formula C2H6OS, which is widely used in the biology and medical fields (1–3). DMSO is reported to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidative capacities (1,2). It was shown that DMSO attenuated acute lung injury induced by hemorrhagic shock (1). Moreover, topical application of DMSO mitigated arthritis in animal models from the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the joint (2). Analgesic and local anesthetic activity of DMSO has also been previously reported (3). DMSO is applied as a cryoprotective agent to reduce ice crystal artifacts (4). Most commonly, DMSO is widely used as a chemical solvent, and it is known to be miscible in a wide range of organic solvents along with water (5).

At present, stem cells are of great interest in medicine, including their use in cell therapy and regeneration fields (6). In a previous study, we identified stem cells from human gingival (7). It was shown that stem cells derived from gingiva had characteristics of stemness, including multipotency with a high proliferation rate. More recently, our group fabricated stem cell spheroids using the silicon elastomer-based concave microwells (8). The effects of various concentrations of DMSO on stem cells derived from intraoral area are not known yet.

Thus, the present study evaluated the effects of different concentrations of DMSO on the cell morphology, viability, mRNA, and protein expression of stem cells derived from the intraoral area, and found potential detrimental effects.

Materials and methods

Stem cells isolated from human gingiva

The gingiva were obtained from healthy patients visiting the Department of Periodontics, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea (Seoul, Korea). The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study (KC11SISI0348). All the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. All of the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The gingiva were placed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (Welgene, Daegu, South Korea) containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The epithelium of the obtained tissue was removed, and the tissue was minced into 1–2 mm fragments. The tissues were digested with media containing dispase (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were incubated in an environment with 5% CO2 and 95% O2 at 37°C in an incubator. Cells that were not attached to the culture dish were removed, and the medium was changed every 2–3 days.

Evaluation of cell morphology

The cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2.0×103 cells/well. The cells were incubated in control medium (α-minimal essential medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 200 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM of ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations of 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 3 and 10%. On days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10, inverted microscopy (CKX41SF; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was used to evaluate the morphology of the tested stem cells.

Cell viability

Evaluation of the viability of the cells grown in control medium was performed on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 with the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) assay. Tetrazolium monosodium salt was added to the culture, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. A microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to find the spectrophotometric absorbance at 450 nm. The tests were performed in triplicate.

Immunofluorescence

An immunofluorescent assay was performed for Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) (ab76956; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and collagen I (ab6308; Abcam) on days 1, 3, 5 and 7. The cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with primary antibodies. Mouse monoclonal Runx2 antibody was diluted at 1:50 and was incubated overnight incubation at 4°C. Mouse monoclonal collagen I antibody was diluted at 1:67 and was incubated overnight incubation at 4°C. The cultures were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody (F2761; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) diluted at 1:100 and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The washed cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Analyses were performed using a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200; Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany).

Total RNA extraction and quantification by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

On day 11, isolation of total RNA was performed from the cells grown in control medium on day 11 using a GeneJET RNA Purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Quantities were determined using a spectrophotometer (ND-2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) with ratios of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm.

The sense and antisense primers were designed based on GenBank. The primer sequences used were: Collagen I, forward 5′-TCATGGCCCTCCAGCCCCCAT-3′; and reverse 5′-ATGCCTCTTGTCCTTGGGGTTC-3′; Runx2, forward 5′-AATGATGGTGTTGACGCTGA-3′; and reverse 5′-TTGATACGTGTGGGATGTGG-3′. β-actin served as a housekeeping gene for normalization. mRNA expression was detected by qPCR using SYBR-Green Real-Time PCR Master Mixes (Enzynomics, Daejeon, South Korea) based on the manufacturer's protocol. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

On day 10, lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as well as phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as solubilizing agent. The lysates were quantified using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein samples were separated and then transferred for immunoblotting. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The antibodies included those against collagen I, Runx2, and GAPDH, as well as secondary antibodies linked with horseradish peroxidase. The antibodies were purchased from Abcam and BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the means ± standard deviations of the experiments. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. A one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc test was performed to determine the differences between the groups using a commercially available program (SPSS 12 for Windows; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Evaluation of cell morphology

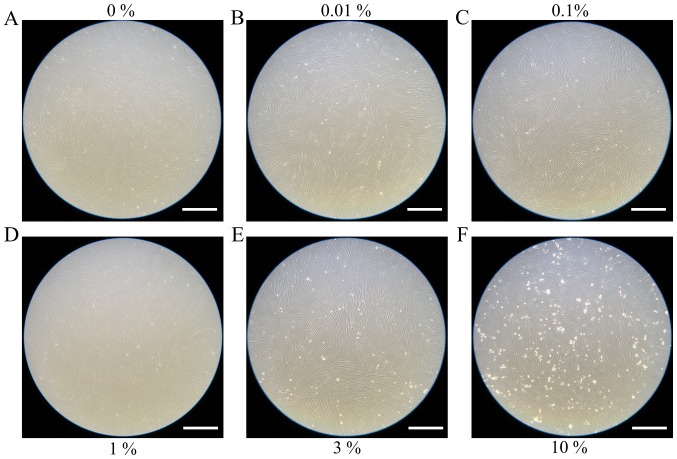

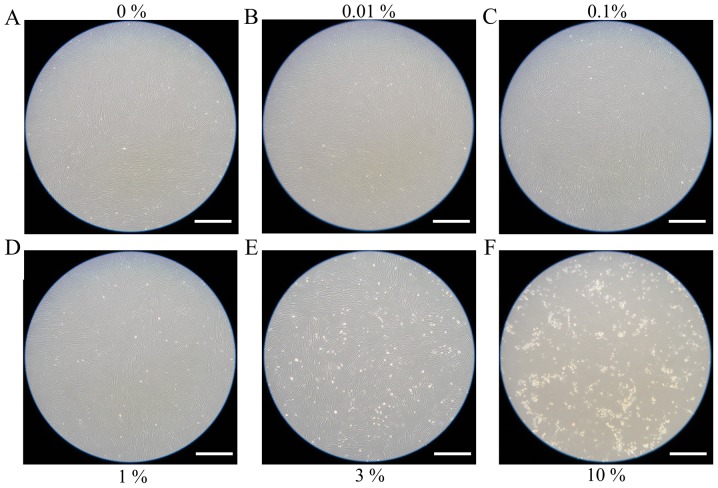

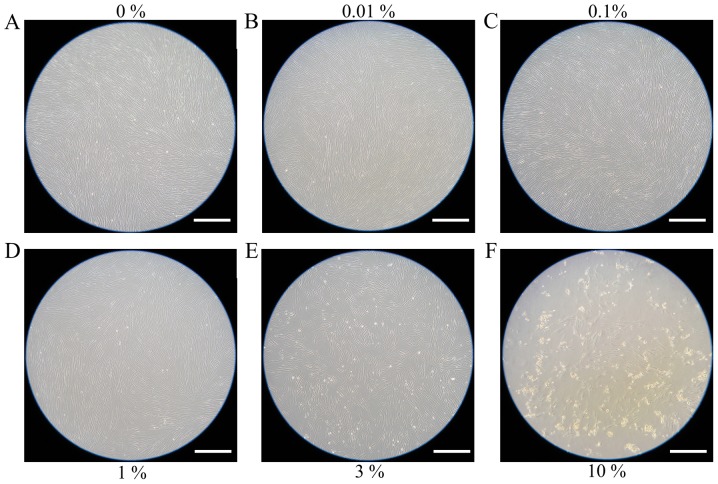

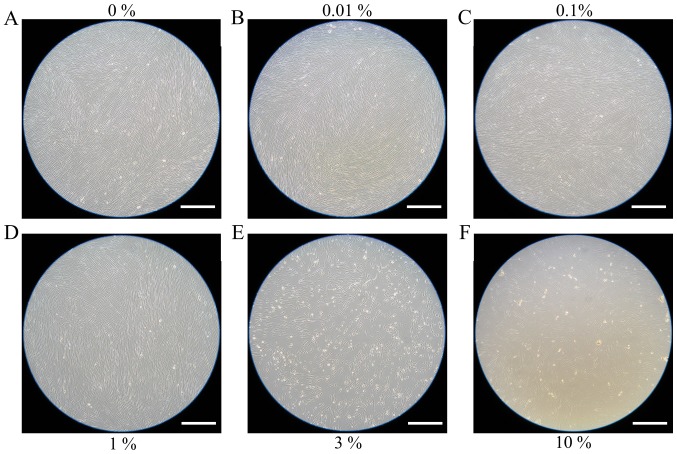

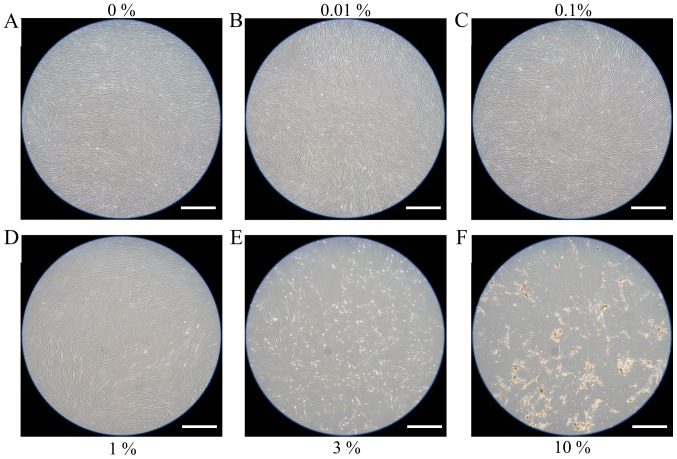

Cells in the control group showed normal fibroblast morphology in growth media on day 1 (Fig. 1). The shape of cells for the 0.01, 0.1, 1, 3 and 10% groups were similar to those in the control group. Cell morphology results for days 3 and 5 are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The shape of the cells was similar to day 1. Cell morphology results for days 7 and 10 are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. The shape of the cells was similar to day 1, however, cells from the 3 and 10% groups were significantly different compared to the others. There were fewer cells in the 3 and 10% groups and they were more round in appearance.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of cell morphology on day 1 following treatment with different concentrations of DMSO in growth media. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 400 µm.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of cell morphology on day 3 in growth media. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 400 µm.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of cell morphology on day 5. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 400 µm.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of cell morphology on day 7. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 400 µm.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of cell morphology on day 10. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 400 µm.

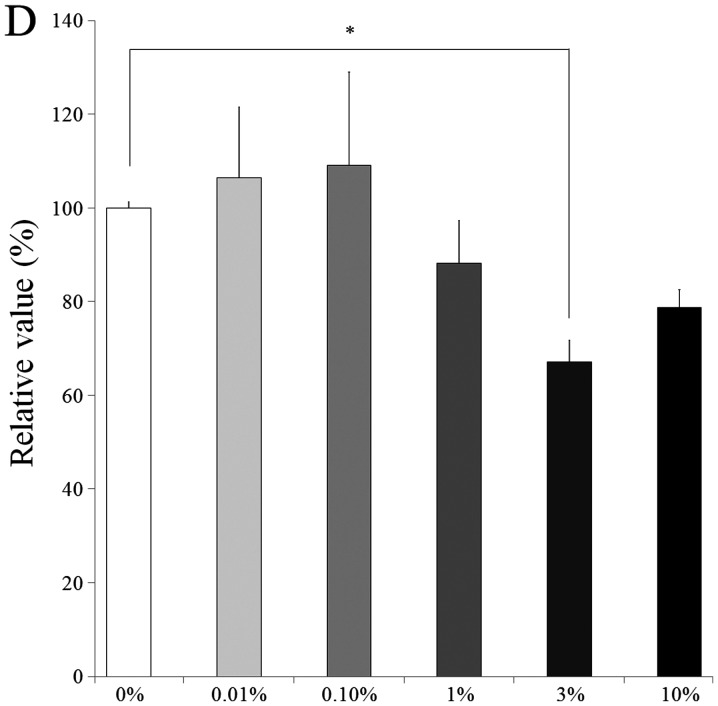

Cell viability

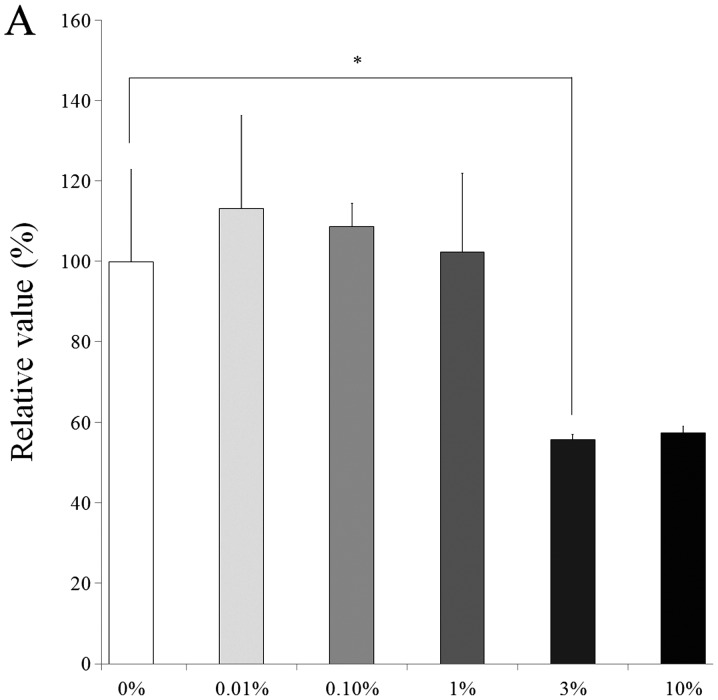

Results from the CCK-8 assay revealed cell viability on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 (Fig. 6). The relative values of CCK-8 at day 1 for 0.01, 0.1, 1, 3 and 10% were 113.2±23.2, 108.8±5.8, 102.4±19.6, 55.7±1.4 and 57.3±1.8%, respectively, when the control (0% group) at day 1 was considered 100% (100.0±22.8%). The relative values of CCK-8 at day 7 for 0.01, 0.1, 1, 3 and 10% were 106.5±15.0, 109.1±19.9, 88.2±9.1, 67.1±4.7, 78.8±3.7, respectively, when the control (0% group) at day 7 is considered 100% (100.0±1.2%).

Figure 6.

The CCK-8 assay results at days 1, 3, 5, and 7 cultured with growth media. (A) Day 1, (B) day 3, (C) day 5, and (D) day 7. *P<0.05.

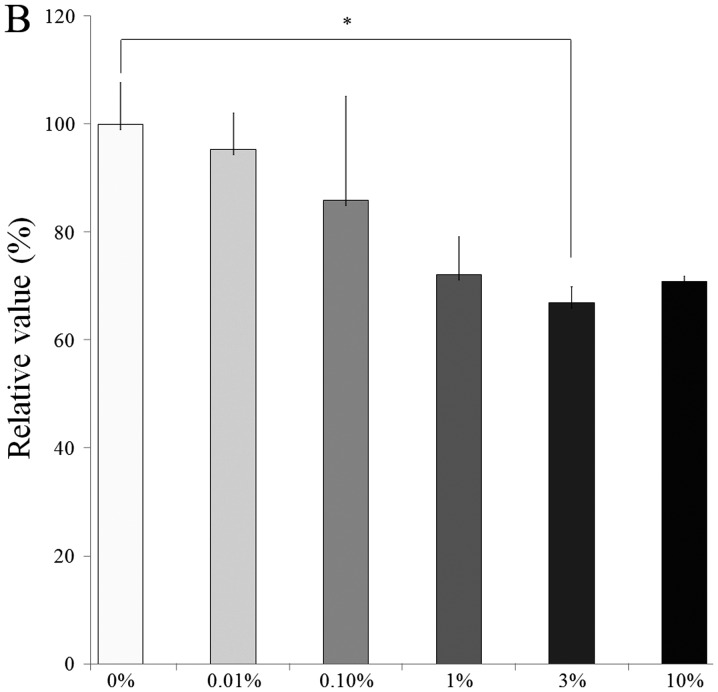

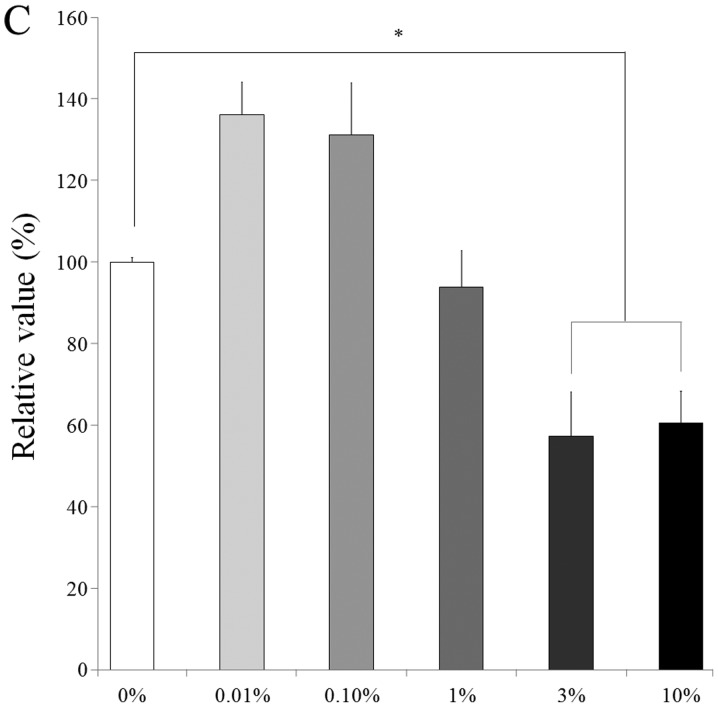

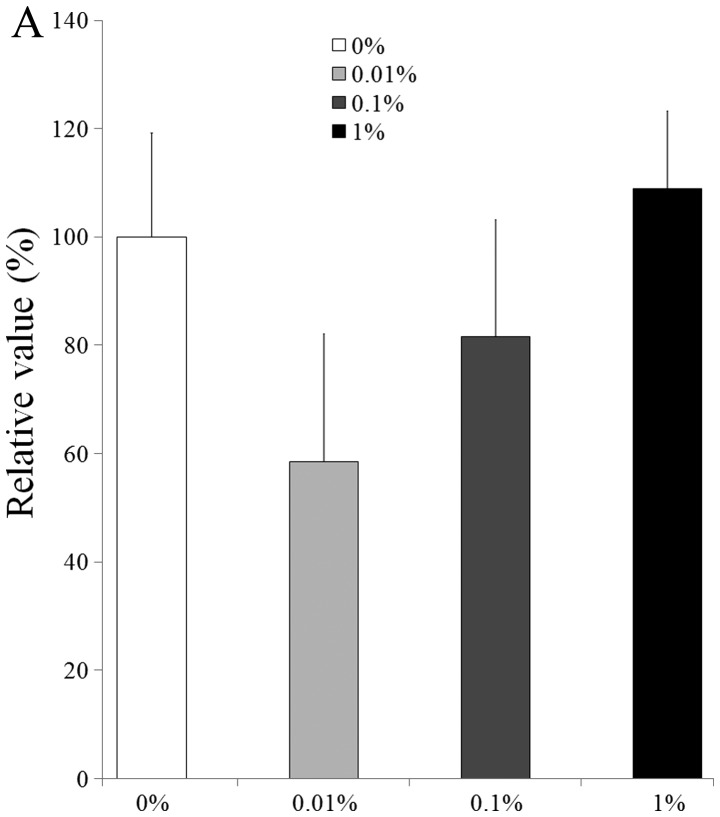

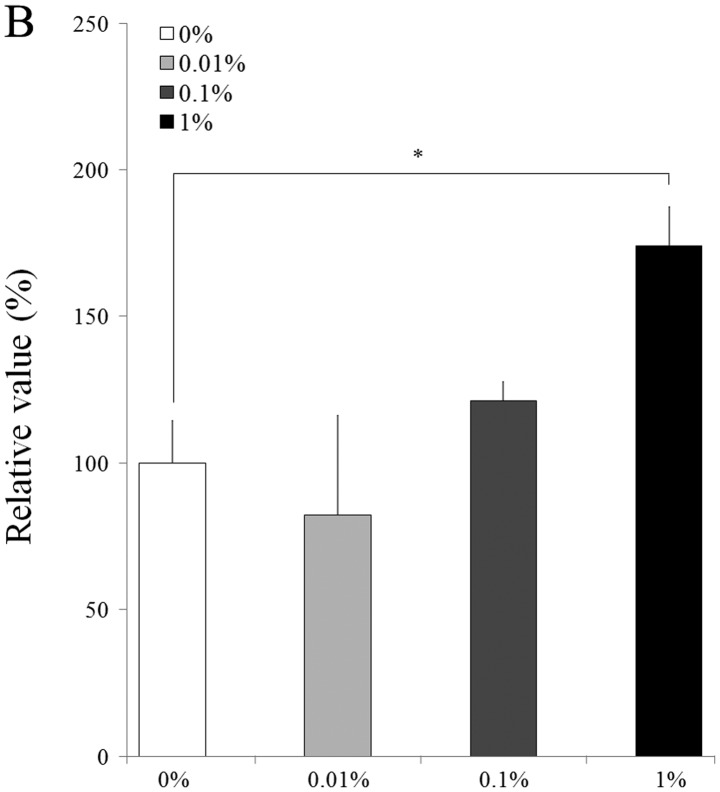

Validation of mRNA expression by qPCR

The qPCR results for the mRNA levels of collagen I and Runx2 are shown in Fig. 7. The relative expression of collagen I in the control medium at day 11 for the 0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1% groups was 100.0±19.2, 58.4±23.6, 81.6±21.6 and 109.0±14.3%, respectively (Fig. 7A). The relative expression of Runx2 at day 11 for the 0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1% groups was 100.0±14.4, 82.4±33.9, 121.2±6.6 and 174.1±39.7%, respectively (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction results of collagen I and Runx2 and expression on day 11 in growth media. (A) Collagen I expression on growth media, (B) Runx2 expression on growth media. *P<0.05.

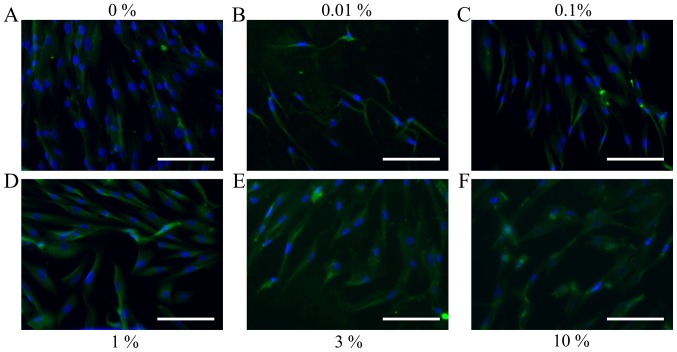

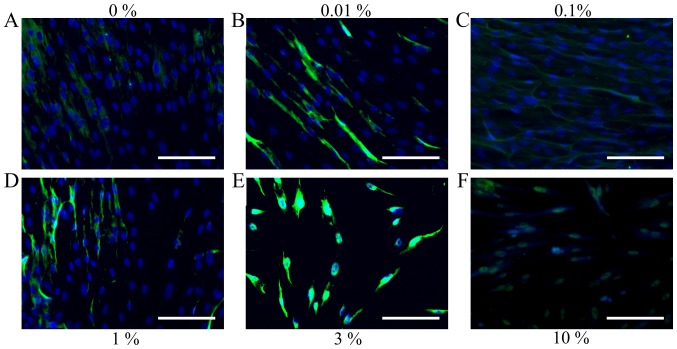

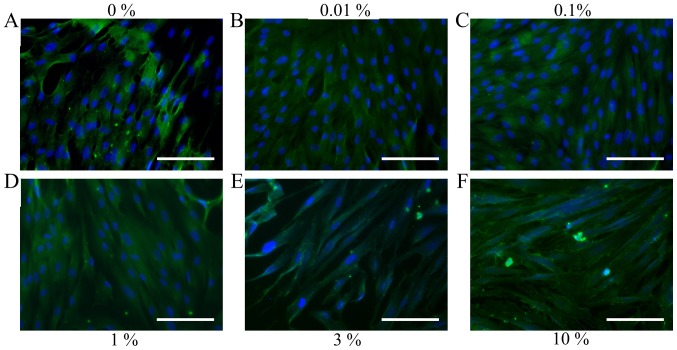

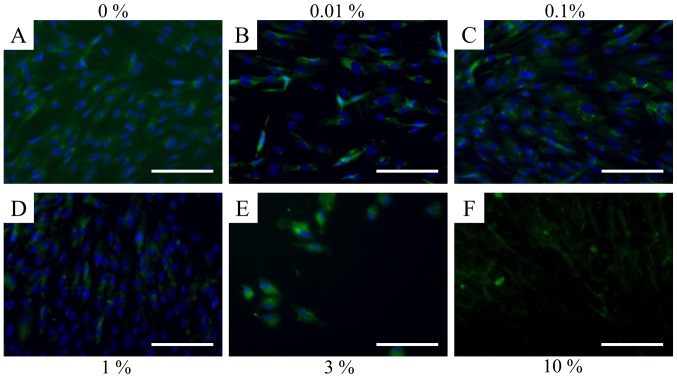

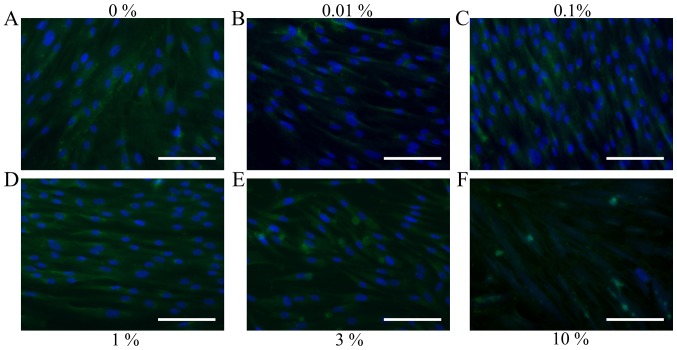

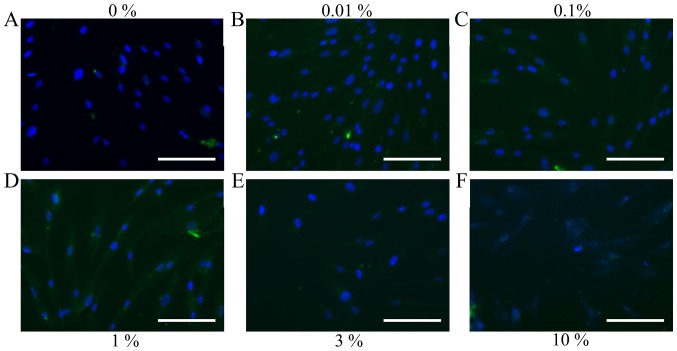

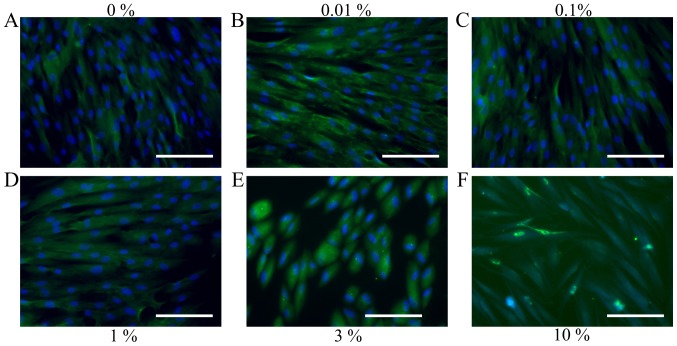

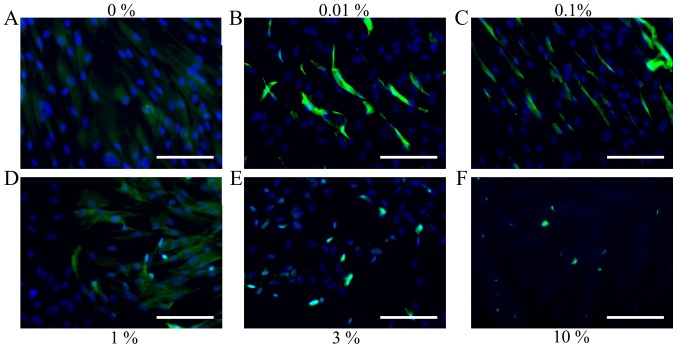

Immunofluorescence

The immunofluorescent assays for collagen I and Runx2 for days 1, 3, 5 and 7 are shown in Figs. 8–15. A significant change in collagen I expression was noted at a higher concentration of the DMSO groups. The expression of Runx2 seemed to show similar trends: there were notable changes with increasing doses of DMSO.

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescence results of collagen I on day 1. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 15.

Immunofluorescence results of Runx2 on day 7. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

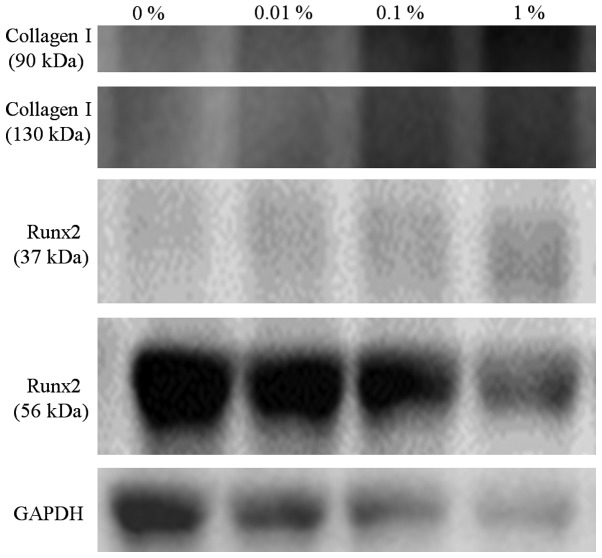

Western blot analysis

A western blot analysis was performed to detect the protein expression of collagen I Runx2, and GAPDH at day 10 (Fig. 16). The relative expression of collagen I (90 kDa) in growth media at day 10 for the 0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1% groups was 100.0, 136.0, 291.4 and 499.6%, respectively. The relative expression of collagen I (130 kDa) in growth media at day 10 for the 0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1% groups was 100.0, 154.6, 468.0 and 769.2%, respectively.

Figure 16.

Western blot analysis to detect the protein expression of collagen I and Runx2 at day 10 in growth media.

The relative expression of Runx2 (37 kDa) in growth media at day 10 for the 0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1% groups was 100.0, 137.2, 182.3 and 341.0%, respectively. The relative expression of Runx2 (56 kDa) in growth media at day 10 for the 0, 0.01, 0.10 and 1% groups was 100.0, 91.5, 99.2 and 82.2%, respectively.

Discussion

This study tested the effects of the differential concentration of DMSO on gingiva-derived stem cells and it was shown that decreased cell viability along with the changes in morphology were seen at higher concentrations. The change in mRNA and protein expression of collagen I and Runx2 was also identified.

Stem cells may be obtained from various tissues, including bone marrow and fat (9). Bone marrow-derived stem cells are widely used in medical fields in applications including the regeneration of cartilage tissue (9,10). Adipose tissue is suggested to be an abundant and accessible source of adult mesenchymal stem cells (11). However, obtaining bone marrow-derived and adipose-derived stem cells may produce issues regarding morbidity and pain (11,12). However, obtaining stem cells from the intraoral area may be attractive because the procedure can be performed under local anesthesia (13). Gingival tissue can be obtained during the daily dental practice and the gingival tissue can be obtained several times with minimal morbidity (14).

In the present study, we determined the effects of DMSO on the morphology and viability of cells under predetermined concentrations (0.01 to 10%). No significant changes of cell morphology were noted in the low concentration. However, in the higher concentrations of 3 and 10%, there were fewer cells with rounder shapes. In the lower concentration of 0.01%, the cellular viability was increased, but the treatment with higher concentrations of DMSO of 3 and 5% resulted in a noticeable decrease in cellular viability. Similarly, in the previous report, low doses of DMSO showed the protective effects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury (15). In the experimental design, DMSO is widely used as a dissolving agent and an equal amount of DMSO is applied to each sample to offset the effects of DMSO as a dissolving agent (16). It should be emphasized that the culture without a dissolving agent should be used as a negative control, as the effect of DMSO can be falsely attributed to the agents applied.

In this study, a CCK-8 assay, which is based on the evaluation of mitochondrial activity, is used for the evaluation of cellular viability (17). A qPCR and a western blot analysis were performed to detect the mRNA and protein expression of collagen I and Runx2 to achieve information on the possible mechanisms. Collagen I is considered the most abundant structural protein among the numerous types of collagen (18). Collagen I is shown to be involved in biological events, including cell attachment, cell proliferation, and remodeling (19). Immunofluorescent data clearly showed that collagen I expression was significantly reduced in the higher DMSO concentration.

Based on these findings, it was concluded that DMSO could produce detrimental effects on the cellular morphology and cellular viability of mesenchymal stem cells. Our results also suggested that DMSO has toxic effects via reduced collagen I expression.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence results of collagen I on day 3. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 10.

Immunofluorescence results of collagen I on day 5. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 11.

Immunofluorescence results of collagen I on day 7. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 12.

Immunofluorescence results of Runx2 on day 1 in growth media. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 13.

Immunofluorescence results of Runx2 on day 3. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Figure 14.

Immunofluorescence results of Runx2 on day 5. (A) Control, (B) 0.01%, (C) 0.1%, (D) 1%, (E) 3%, and (F) 10% groups. Bar, 200 µm.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communication Technology and Future Planning (NRF-2017R1A1A1A05001307).

References

- 1.Tsung YC, Chung CY, Wan HC, Chang YY, Shih PC, Hsu HS, Kao MC, Huang CJ. Dimethyl sulfoxide attenuates acute lung injury induced by hemorrhagic shock/resuscitation in rats. Inflammation. 2017;40:555–565. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elisia I, Nakamura H, Lam V, Hofs E, Cederberg R, Cait J, Hughes MR, Lee L, Jia W, Adomat HH, et al. DMSO represses inflammatory cytokine production from human blood cells and reduces autoimmune arthritis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris RW. Analgesic and local anesthetic activity of dimethyl sulfoxide. J Pharm Sci. 1966;55:438–440. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600550421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrant J, Walter CA, Lee H, Morris GJ, Clarke KJ. Structural and functional aspects of biological freezing techniques. J Microsc. 1977;111:17–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1977.tb00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos NC, Figueira-Coelho J, Martins-Silva J, Saldanha C. Multidisciplinary utilization of dimethyl sulfoxide: Pharmacological, cellular, and molecular aspects. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin SH, Kweon H, Park JB, Kim CH. The effects of tetracycline-loaded silk fibroin membrane on proliferation and osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. J Surg Res. 2014;192:e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin SH, Lee JE, Yun JH, Kim I, Ko Y, Park JB. Isolation and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells from gingival connective tissue. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:461–467. doi: 10.1111/jre.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SI, Yeo SI, Kim BB, Ko Y, Park JB. Formation of size-controllable spheroids using gingiva-derived stem cells and concave microwells: Morphology and viability tests. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:97–101. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malgieri A, Kantzari E, Patrizi MP, Gambardella S. Bone marrow and umbilical cord blood human mesenchymal stem cells: State of the art. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2010;3:248–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z, Ba R, Wang Z, Wei J, Zhao Y, Wu W. Angiogenic potential of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in chondrocyte brick-enriched constructs promoted stable regeneration of craniofacial cartilage. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:601–612. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2016-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, Fraser JK, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–4295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong SH, Lee JE, Kim BB, Ko Y, Park JB. Evaluation of the effects of Cimicifugae Rhizoma on the morphology and viability of mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:629–634. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JB. Treatment of multiple gingival recessions using subepithelial connective tissue grafting with a single-incision technique. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:317–321. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JB. Root coverage with 2 connective tissue grafts obtained from the same location using a single-incision technique. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:371–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelava T, Cavar I, Culo F. Influence of small doses of various drug vehicles on acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:960–967. doi: 10.1139/Y10-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JB, Zhang H, Lin CY, Chung CP, Byun Y, Park YS, Yang VC. Simvastatin maintains osteoblastic viability while promoting differentiation by partially regulating the expressions of estrogen receptors α. J Surg Res. 2012;174:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha DH, Yong CS, Kim JO, Jeong JH, Park JB. Effects of tacrolimus on morphology, proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from gingiva tissue. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:69–76. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong Po, Foo C, Kaplan DL. Genetic engineering of fibrous proteins: Spider dragline silk and collagen. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggiero F, Exposito JY, Bournat P, Gruber V, Perret S, Comte J, Olagnier B, Garrone R, Theisen M. Triple helix assembly and processing of human collagen produced in transgenic tobacco plants. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:132–136. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01259-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]