SUMMARY

Proteins of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family mediate cellular responses to cytokines and growth factors. Aberrant regulation of the STAT3 oncogene contributes to tumor formation and progression in many cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), where hyperactivation of STAT3 is implicated in both treatment resistance and immune escape. There are no oncogenic gain-of-function mutations in HNSCC. Rather, aberrant STAT3 signaling is primarily driven by upstream growth factor receptors, such as Janus kinase (JAK) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Moreover, genomic silencing of select protein tyrosine phosphatase receptors (PTPRs), tumor suppressors that dephosphorylate STAT3, may lead to prolonged phosphorylation and activation of STAT3. This review will summarize current knowledge of the STAT3 pathway and its contribution to HNSCC growth, survival, and resistance to standard therapies, and discuss STAT3-targeting agents in various phases of clinical development.

Keywords: STAT3, Head and neck cancer

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth leading incident cancer worldwide with 55,000 cases in the United States and 550,000 cases globally in 2014 [1,2]. Despite advances in surgical and radiotherapy techniques, as well as integration of chemotherapy into multimodality treatment paradigms, HNSCC is frequently lethal. Five-year overall survival (OS) is 40–60% and has increased only marginally since 1990 [3]. Incremental improvements in prognosis are largely attributable to changing epidemiology, rather than treatment per se. An increasing proportion of oropharyngeal HNSCC is caused by oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV), rather than the classic risk factors of tobacco and alcohol; HPV etiology is associated with improved survival after standard treatments [4,5]. Although two distinct causes of HNSCC exist, environmental carcinogenesis or transformation by HPV oncogenes, both etiologies are associated with aberrant regulation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family [6–8]. However, the transcription factor (TF) signatures of HPV-related HNSCC and HPV-negative HNSCC have been elucidated and differ in respect to the activity of several key TFs, with upregulation of STAT3 and NF-κB gene targets demonstrated in HPV-negative HNSCC [9].

Proteins of the STAT family mediate cellular response to cytokines, such as IL-6, and growth factors. In particular, STAT3 transforms human epithelial cells, thereby meeting the definition of an oncogene [10,11]. Aberrant regulation of STAT3 in HNSCC underlies malignant behaviors, contributing to growth, survival and resistance to standard therapies including chemoradiation and blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [12–16]. Aberrant tumoral STAT3 signaling is also immunosuppressive, protecting HNSCC cells from recognition and lysis by cytotoxic T lymphocytes [17,18]. Tumor and lymphocyte STAT3 signaling increases production of immunosuppressive cytokines including TGF-β1, VEGF, IL-6 and IL-10; this cytokine profile negatively regulates innate danger signals, dendritic cell maturation, and cytolysis by effector cells [17–20]. In vitro STAT3 inhibition reverses the immunosuppressive phenotype of HNSCC [21]. The association of STAT3 hyperactivation with poor prognosis, resistance to standard therapies, and immune escape makes it a compelling target in HNSCC, particularly in HPV-negative HNSCC where functional studies suggest targeting this pathway may be effective [9]. As for other transcription factors, STAT3 historically has been considered “undruggable.” However, innovative and promising therapeutic strategies are in development. This review will summarize current knowledge of STAT3 pathway activation in HNSCC, and discuss STAT3-targeting agents in various phases of clinical development.

STAT3 activation in HNSCC

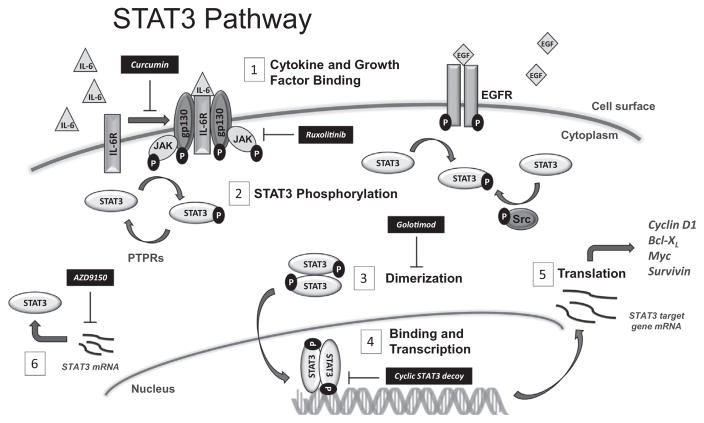

The STAT3 transcription factor exhibits its pro-transcription effects in response to signals from upstream receptors including the IL-6 cytokine receptor family, growth factor receptors such as the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), or nonreceptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs) such as Janus-activated kinases (JAK) and Src family kinases (SFK) [22–24]. Fig. 1 depicts the activation of STAT3 and its target genes in schematic form. First, STAT3 is recruited to the plasma membrane upon binding of cytokines or growth factors to their respective cell surface receptors. STAT3 becomes activated by phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue within its Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (Tyr705), either by the activated RTKs directly, or by intracellular NRTKs. Phosphorylation of STAT3 then induces spontaneous dimerization of the transcription factor via a reciprocal phosphotyrosine–SH2 interaction between two STAT3 molecules. STAT3 can also heterodimerize with STAT1, though the molecular consequence of this interaction remains unknown [25]. Following STAT3:STAT3 dimerization, phospho-STAT3 translocates to the nucleus where dimers bind to consensus sequences on the promoter regions of target genes with the resultant cascade of gene transcription. Activated STAT3 thus upregulates the transcription of cyclin D1, survivin, and Bcl-xL.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the STAT3 pathway and therapeutic targets. (1) Cytokines and growth factors, such as IL-6 and EGF, bind to receptors to activate phosphorylation and cell signaling. Curcumin inhibits cell surface signaling, (2) STAT3 molecules are activated by phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue by activated RTKs, such as EGFR, or intracellular NRTKs like JAK or Src. Inactivation by dephosphorylation occurs by PTPRs. Targeted therapies, including the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, inhibit these pathways. (3) Spontaneous dimerization of two phosphorylated STAT3 molecules occurs via the reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 interactions, and the homodimer translocates to the nucleus. Golotimod, an immunomodulating peptide, inhibits homodimerization of STAT3 molecules in the cytoplasm. (4) pSTAT3 homodimer binds to consensus sequences on the promotor regions of target genes. STAT3 decoy molecules are under development to target this step in the STAT3 transcription pathway. (5) The resultant transcripts are translated into pro-proliferative, pro-survival oncogenic proteins. (6) AZD9150 is an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits the translation of STAT3 mRNA.

Mechanisms of STAT3 hyperactivation in human cancer are incompletely understood. Despite near-universal STAT3 signaling activation in HNSCC, gain-of-function STAT3 mutations have not been observed; neither have activating mutations in upstream growth factor receptors such as EGFR or JAK [26,27]. In general, STATs are positively regulated by upstream cytokine or growth factor receptors or intracellular NRTKs, and negatively regulated by protein tyrosine phosphatase receptors (PTPR). Thus, STAT3 can be constitutively activated either as a consequence of enhanced signaling from positive effectors, or by decreased activity of negative effectors – as observed in HNSCC and glioma cell lines [14,28]. Aberrant protein tyrosine phosphorylation is a hallmark of human cancer. Of all known protein tyrosine phosphatases, the PTPRs comprise the largest family within the human tyrosine phosphatome [29]. Some PTPRs, including PTPRD and PTPRT, have been reported to function as tumor suppressors because gene mutations or methylation contribute to growth and survival in preclinical models [29]. STAT3 has been reported to be a substrate of PTPRT in colorectal cancer models [30], and a substrate of PTPRD in glioblastoma cells [31]. This suggests that many members of the PTPR family may be involved in tumor suppression by dephosphorylating STAT3. Of significant interest, mutations in the PTPR gene family have been described in 31% of HNSCC tumors, independent of HPV status, while methylation of PTPRD or PTPRT has been observed in 60% of the HNSCC cases within the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [31,32]. The varied distribution and absence of hotspot mutations suggest that these PTPRs function as tumor suppressors. Moreover, many mutations cluster in the catalytic phosphatase domain, supporting that de-phosphorylation of the STAT3 oncoprotein may be important to the hypothesized tumor suppressor function. Such a function was mechanistically corroborated in HNSCC tumor specimens, where selected PTPRT mutations correlated with in situ up-regulation of phospho-STAT3 expression, as compared to tumors that were PTPRT wild type (WT) [32]. Moreover, when WT HNSCC cells were engineered to over-express WT PTPRT, decreased STAT3 phosphorylation was observed, whereas transfection of a PTPRT phosphatase domain mutation resulted in increased STAT3 phosphorylation. PTPRT promoter methylation has been shown to upregulate pSTAT3 expression and is associated with sensitivity to STAT3 inhibition in HNSCC cells [33]. Conversely, mutations in PTPRD lead to loss of function and subsequent hyper-phosphorylation of its substrates, including STAT3, and HNSCC cell lines harboring PTPRD mutations are more sensitive to STAT3 inhibition [34]. Epigenetic or genetic silencing of PTPRs, negative regulators of the STAT3 pathway, may therefore represent direct drivers for tumor growth in HNSCC by hyperactivation of STAT3. This discovery suggests that tumors harboring PTPR loss-of-function events may be uniquely amenable to STAT3 pathway inhibitors, and PTPRD mutation and PTPRT promoter methylation may serve as predictive biomarkers for responsiveness to STAT3 blockade. PTPRD mutations found in HNSCC are summarized in Table 1 [34].

Table 1.

PTPRD gene mutations identified in HNSCC.

| Mutation | Location on gene | |

|---|---|---|

| D50E | Immunoglobulin (Ig) | Extracellular domain |

| T111N | Ig | |

| Q196H | Second Ig-like domain of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase (IG2) | |

| K204E | IG2 | |

| P249L | IG2 | |

| L308P | IG2 | |

| S384R | Fibronectin type 3 domain (FN3) | |

| L503I | FN3 | |

| E529Q | FN3 | |

| T820P | FN3 | |

| L1014M | FN3 | |

| L1036P | FN3 | |

| T1100M | Transmembrane region | |

| L1147F | Transmembrane region | |

| S1247T | Transmembrane region | |

| V1270L | Transmembrane region | |

| P1311T | Transmembrane region | |

| K1502M | Catalytic domain |

STAT3 activation and resistance to standard therapeutics

In addition to serving as an oncogene in HNSCC, STAT3 also represents a key resistance mechanism for standard therapeutics including platinum chemotherapy and radiation. Radiation is a modality of therapy paramount to the local control and improved survival of HNSCC, either as a single-modality option in definitive doses or in the adjuvant setting, or in a multimodal approach with chemotherapy. The effects of tumor cell damage, facilitated by damage to DNA, result directly from ionization of DNA or from the action of free radical formation [35,36]. STAT3 has been described as a key mediator of chemoradiotherapy (CRT) resistance in numerous cancers, including gliomas [37–39], breast cancer [40–43], colorectal cancer [44,45], and prostate and cervical cancers [42], in addition to HNSCC.

Targeting the STAT3 pathway has been shown to abrogate EGFR inhibitor resistance in HNSCC. EGFR overexpression occurs in the majority of HNSCC, and is associated with advanced stage and reduced overall survival [46–48]. As such, EGFR is a validated therapeutic target. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFR, is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of locally advanced HNSCC when combined with radiation, as well as for advanced disease when administered during front line treatment with platinum doublet chemotherapy or after platinum failure. STAT3 upregulation and activation via both EGFR-dependent and -independent pathways contributes to intrinsic or acquired resistance to EGFR targeting in HNSCC and other solid tumors. STAT3 activation has been found in the setting of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in preclinical models of gliomas and HNSCC [14,28]. Resistance to EGFR TKI treatment of non-small cell lung cancer was associated with elevated STAT3 activity in tumors [49]. Combined treatment of HNSCC cell lines with an EGFR TKI and a STAT3 decoy molecule, an oligonucleotide designed to block STAT3 binding to DNA response elements, was associated with enhanced tumor effects relative to EGFR TKI alone [50]. Targeting STAT3 using the decoy oligonucleotide in cetuximab- or TKI-resistant cells sensitizes the cells to EGFR inhibitor treatment in vitro and in vivo [15]. These findings suggest that targeting the STAT3 pathway may enhance the antitumor effects of EGFR inhibitors and therefore abrogate resistance to anti-EGFR therapies.

Specific targets of the STAT3 pathway

Targeting the STAT3 pathway has been a major focus of drug development, due to its contribution to treatment resistance and immune escape in most epithelial malignancies [13,17,51,52]. Strategies for targeting STAT3 can be conceptualized according to its activation cascade as depicted in Fig. 1. Abrogation of oncogenic STAT3 signaling could be disrupted by (1) inhibition of upstream extracellular or intracellular receptors, thereby decreasing phosphorylation; (2) inhibition of the pSTAT3 SH2 domain, thereby blocking dimerization; (3) inhibition of STAT3-DNA binding, thereby preventing target gene transcription; and 4) inhibition of STAT3 transcription, thereby down-modulating total STAT3 expression. The agents described below are summarized in Table 2 with selected agents shown along the pathway schematic in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Therapeutic agents targeting STAT3.

| Drug (company) | Target | Type | Phase of development, human cancer | HNSCC development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of upstream receptors | ||||

| Ruxolitinib (Incyte Pharmaceuticals, Novartis) | JAK 1/2 | Small molecule | I/II/III (FDA-approved myelofibrosis) | Phase I (afatinib combination) |

| Tofacitinib (Pfizer) | JAK 3 | Small molecule | (FDA-approved RA) | – |

| AZD1480 (AstraZeneca) | JAK 1/2 | Small molecule | I (terminated) | – |

| Fedratinib (Sanofi) | JAK 2 | Small molecule | I/II/III | – |

| Tocilizumab (Genentech) | JAK 3, IL6R | Monoclonal antibody | I/II (FDA-approved RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis) | – |

| Curcumin | JAK 1/2, IL6 | Natural compound | I/II | Phase 0 (biomarker) |

| Quercetin | JAK 2, IL-6 | Natural compound | I/II | – |

| Inhibition of STAT3 Domain | ||||

| STA-21 | Small molecule | (Phase I/II in psoriasis) | – | |

| WP1066 | Small molecule | I (brain cancer) | – | |

| OPB-51602 (Otsuka Pharmaceutical) | Small molecule | I | Phase I (nasopharyngeal carcinoma; terminated) | |

| OPB-31121 (Otsuka) | Small molecule | I/II | – | |

| Pyrimethamine | Small molecule | I/II (CLL/SLL) | – | |

| Golotimod (SCV-07; SciClone Pharmaceuticals) | Peptide mimetic | II | Phase II (attenuating oral mucositis) | |

| Inhibition of STAT3-DNA Binding | ||||

| STAT3 decoy molecule | Oligonucleotide | Phase 0 (intratumoral injection) | ||

| Cyclic STAT3 decoy | Oligonucleotide | – | ||

| Inhibition of STAT3 Transcription | ||||

| AZD9150 (AstraZeneca); previously known as ISIS 481464 (Isis Pharmaceuticals) | Antisense oligonucleotide | I/II (Advanced cancers, lymphoma, HCC, malignant ascites) | Phase I/II (monotherapy; in combination with MEDI14736) | |

Blocking STAT3 activation: targeting upstream receptors

JAK kinase inhibitors

Inhibiting the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of STAT3 is a logical target for inhibiting the downstream transcription products of STAT3 and can be accomplished by small molecule inhibition of the JAK kinase. Ruxolitinib, an oral small molecule inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, is FDA-approved for the treatment of intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis [53]. Tofacitinib, an inhibitor of JAK3, is FDA-approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and is being studied in other inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis [54,55]. Though nonspecific JAK-STAT3 inhibition has been mentioned to involve cytokine inflammatory activity and downstream transcription products of ruxolitinib [56] and efficacy studies in the tofacitinib trials have suggested that other pathways of inhibition may be affected [57], very little has been published on the effects of JAK inhibition on solid tumors. Another oral JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, AZD1480, was shown to abrogate IL-6 induced STAT3 phosphorylation and also suppressed the growth of human solid tumor xenografts with constitutive STAT3 activity [58,59]. In preclinical studies, AZD1480 was shown to inhibit proliferation of eight HNSCC cell lines at low concentrations [60].

These drugs are not without adverse effects, and toxicity is a concern. Ruxolitinib has been associated with cytopenias, gastroin-testinal disturbances, peripheral neuropathy, and metabolic abnormalities [61,62]. However, data from a phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus ruxolitinib to capecitabine plus placebo indicate that ruxolitinib was well tolerated with very few toxicities [63]. Adverse events reported for tofacitinib include hepatic and renal impairment, neutropenia, and an increased incidence of infections, including tuberculosis [64]. Clinical trials involving AZD1480 were terminated due to significant neurotoxicities [65]. Still another JAK2-selective inhibitor, fedratinib, showed promise in a phase III placebo-controlled trial in patients with myelofibrosis where the primary endpoint of spleen response rate was reached [66]. Unfortunately, while early clinical trials of fedratinib demonstrated the drug to be well tolerated [67,68], occurrence of neurotoxicity also forced the discontinuation of clinical development of this drug. WP1066 is a small molecule that blocks STAT3 activation by JAK2 signaling inhibition [69,70]. This molecule was studied in preclinical glioma cell models, but unfortunately exhibited poor efficacy and thus its development was terminated [71].

In addition to synthetically-derived compounds, naturally-occurring products inhibit STAT3 function by various mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo. 2-Methoxystypandrone, a naphthoquinone isolated from roots of the herb Polygonum cuspidatum, has activity against STAT3 activation and blocks the STAT3 pathway upstream at JAK2 [72,73]. This compound is not currently under clinical investigation but offers a potential natural alternative for future study.

Currently, many ongoing clinical trials are studying JAK inhibitors in cancer patients. Ruxolitinib is being evaluated in breast cancer (in combination with trastuzumab, NCT02066532; preoperatively in triple negative disease, NCT02041429; in combination with capecitabine, NCT02120417; in combination with exemestane, NCT01594216), colorectal cancer (NCT02119676), nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (NCT02119650), acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (NCT02257138), and lymphoma (NCT01965119). A phase II trial in castrate-resistance prostate cancer was terminated due to lack of clinical response (NCT00638378).

IL-6 receptor inhibitors

Cytokine proteins, including interleukins, regulate cellular growth, proliferation, and signaling in tumor environments. IL-6, an inflammatory cytokine, has been detected in high concentrations in serum of patients with HNSCC and correlates with disease relapse [74]. IL-6 activates the JAK1 and 2 pathway through signal transduction, which leads to the activation of STAT3 by phosphorylation [75], thereby making the IL-6 receptor a target for drug development.

Tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) to the IL-6-receptor-alpha (IL6Rα), is FDA-approved in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [76–78]. This drug has been studied in other autoimmune disorders, including ankylosing spondylitis and systemic lupus erythematosus [79,80] and is currently being studied in CLL (NCT02336048). A phase I trial in ovarian cancer has been completed, with results forthcoming (NCT01637532).

Another anti-IL-6 mAb, siltuximab, binds highly to IL-6, neutralizing its bioactivity [81]. It has been studied in various malignancies, including myelodysplastic syndrome, prostate cancer, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [82–85], and is under study in multiple myeloma (NCT01484275).

Other inhibitors of STAT3 phosphorylation

Flavonoids, such as quercetin, have been found to reduce inflammation [86], and this pathway has been exploited for its effects on the tumor microenvironment. Quercetin is found in fruits, vegetables, leaves, and grains and used as a supplement in many foods and beverages. It has been studied in several disease states, including asthma, fibromyalgia, metabolic syndrome, and cancer. Its antitumor effects were initially described in 2000 and thought to be related to immune stimulation, free radical scavenging, alterations in mitosis, apoptotic induction, and gene regulation [87]. Quercetin was shown to be a potent inhibitor of IL-6 driven STAT3 signaling in glioblastoma cell lines [88], where it also reduced downstream expression of cyclin D1 and MMP-2. Similar results were found in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, where treatment with quercetin suppressed the JAK2/STAT3 pathway activation with a subsequent decrease in pSTAT3 proteins [89]. Quercetin has also been observed to block tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 induced by IL-12 [90] and inhibited the proliferation of melanoma cells [91]. Oral quercetin was given daily to Balb/c mice with colon-25 tumors with an observed reduction in tumor size by day 20 [92]. Mukherjee et al. described the downregulation of IL-6-mediated STAT3 activation by quercetin in a NSCLC cell line [93].

Curcumin is a polyphenol derived from the plant Curcuma longa and is the main component of the spice turmeric. A naturally-occurring phenol with a bright yellow color, curcumin is used as a food coloring or additive and has been studied in diseases such as psoriasis, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and various malignancies [94,95]. Anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin were classically attributed to the suppression of NF-κB activation, thereby downregulating the transcription of IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines [96]. Kim et al. demonstrated that curcumin suppresses the phosphorylation of upstream kinases JAK1 and JAK2, resulting in downstream inhibition of STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation and activation [97]. Treatment of activated T-cells with curcumin was shown to inhibit IL-12-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 [98] and inhibited STAT3 activation and nuclear translocation in myeloma cells [99]. This was also exhibited when curcumin was administered to murine glioma cell lines [100]. Curcumin decreased STAT3 phosphorylation in both constitutive and IL-6 induced ovarian and endometrial cells, resulting in decreased cell viability, which was shown to be reversible with normalization of pSTAT3 levels within 24 h of curcumin removal [101]. In preclinical studies specifically in HNSCC cell lines, curcumin was shown to inhibit proliferation and invasion by the inhibition of phosphorylation of EGFR and its downstream molecules, including STAT3 [102]. Curcumin also suppressed IL-6 mediated STAT3 phosphorylation [103].

Curcumin is being actively studied in various malignancies, including colorectal cancer (NCT01490996, NCT01859858), breast cancer (NCT01740323, NCT01975363), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (NCT02100423), and prostate cancer (NCT01917890, NCT02064673, and NCT02095717). Studies are also evaluating the cancer prevention abilities of curcumin in familial adenomatous polyposis (NCT00927485, NCT00641147). Quercetin is being studied in prostate and pancreatic cancers (NCT01912820 and NCT01879878, respectively).

Blocking STAT3 dimerization: SH2 domain inhibition

Small molecule inhibitors

Inhibiting the SH2 domain of the STAT3 transcription factor blocks the two major steps required for the formation of STAT3 dimers: first, recruitment of the molecule to the plasma membrane for phosphorylation of Tyr705 by activated RTKs or non-receptor kinases, and second, the subsequent dimerization of two activated STAT3 molecules. Thereby dimer translocation to the nucleus is prevented, and transcription of target genes does not occur. Several small molecules targeting the SH2 domain have been described, and many are in various phases of development.

STA-21, a small molecule antibiotic discovered through computational methods and a virtual library of the SH2 domain, hinders dimerization of STAT3 and downregulates expression of STAT3 target genes in human carcinoma cells with constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation [104]. Despite its pathway inhibitory activity, there is no biochemical evidence to support its binding to the SH2 domain. STA-21 has been studied in patients with psoriasis, where Miyoshi et al. reported clinical improvement in psoriatic skin lesions after topical use of this molecule [105].

Direct dephosphorylation of p-STAT3 by protein tyrosine phosphatases, which includes members of the SH2-domain containing tyrosine phosphatase family (SHP-1 and SHP-2), is another mechanism that leads to downregulation of STAT3 transcription products. SHP-1, the loss of which has been shown to enhance JAK3/STAT3 signaling in various non-Hodgkin lymphomas [106,107], represents another target in STAT3 modulation. The novel small molecule SC-2001 was shown to inhibit the transcriptional activities of STAT3 by enhancing SH-1 activity in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells [108]. This molecule has also been studied in combination with sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor approved for treatment of unresectable HCC, advanced RCC, and thyroid cancer, where it was shown to overcome sorafenib resistance through the SH-1 pathway in HCC cell lines [109].

OPB-51602 is an oral small molecule that has high affinity for the STAT3 SH2 domain with resulting interference in STAT3 activity in numerous in vitro and in vivo models (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., unpublished data). A phase I study in advanced solid tumors showed partial responses in two patients with NSCLC who previously were treated with EGFR TKIs [110]. However, a second phase I study in patients with hematologic malignancies demonstrated significant toxicity at doses where clinical responses were observed, and lower doses required a more difficult dosing schedule and no responses were observed, thus further clinical development of OPB-51602 was terminated [111]. A clinical trial to determine safety and tolerability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients (NCT02058017) was subsequently terminated.

OPB-31121 has also been shown to have a high affinity for the SH2 domain of STAT3 [112]. Preclinical studies show promise of this drug in hematologic malignancies [113], and phase I studies have been conducted in patients with advanced solid tumors [114] and hematologic malignancies (NCT10129509). Due to an unfavorable pharmacokinetic profile and no objective observed responses, clinical development was halted. Prior to termination of the development of OPB-31121, a phase I/II trial in patient with progressive HCC was completed with results not yet available (NCT01406574).

Pyrimethamine is an anti-parasitic drug used for both the treatment and prevention of malaria. This drug was identified as a STAT3 inhibitor through a chemical library screen and shown to reduce pSTAT3 levels in a human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) cell line [115]. A phase I/II clinical trial is currently studying pyrimethamine for safety and dose-finding in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) patients (NCT01066663).

Peptide mimetics

Several peptidomimetic inhibitors targeting the SH2 domain of STAT3 have been derived from sequences in the SH2 domain. The SH2 protein sequences around phosphotyrosine 705 (Pro-pTyr705-Leu-Lys-Thr-Lys) participate directly in STAT3 dimerization, and these sequences served as the starting point [116,117]. ISS-610, a tripeptide mimic, and its interaction with the SH2 domain of STAT3 was combined with structural information from X-ray crystallography of STAT3, leading to the development of an analogue peptidomimetic, S3I-M2001 [117–119]. This compound also exhibited inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation in NIH 3T3/v-Src and MDA-435-MB cells and tumor growth in human breast tumor xenografts.

Golotimod (SCV-07; γ-D-glutamyl-L-tryptophan) is a novel immunomodulating peptide that inhibits STAT3 signaling and was found to modulate the duration and severity of oral mucositis in animal models that received radiation or a combination of radiation and cisplatin [120]. A subsequent phase 2 trial suggested this drug also favorably attenuated the course of mucositis in patients with HNSCC [121].

Phosphopeptide prodrug

Phosphopeptide prodrugs derived from gp130 Tyr904 represent another class of compounds targeting the SH2 domain of STAT3. These prodrugs were found to be potent inhibitors of STAT3 phosphorylation in several cancer cell lines [122]. Intratumoral injection of PM 73G in an orthotopic xenografts significantly inhibited tumor growth, tumor vascularization, and VEGF expression [123,124]. This suggests that selective inhibition of STAT3 leads to impaired VEGF signaling and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis.

Natural products

Cryptotanshinone, a natural product in the tanshinone class (compounds isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza, an herb used in traditional Chinese medicine [125]), has been identified as a potent STAT3 inhibitor [126]. Because cryptotanshinone rapidly inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT3 Tyr705 in a human prostate cancer cell line while phosphorylation of JAK2 was inhibited in a protracted manner, a JAK2-independent mechanism is hypothesized. Furthermore, cryptotanshinone and STAT3 co-localized in the cytoplasm and the formation of STAT3 dimers was suppressed, providing evidence that the binding site is SH2. The agent also decreased expression of target genes cyclin D1, survivin, and Bcl-xL, with similar results found in glioma cell lines [127]. While this compound has not been formally studied in a clinical trial context, its use in traditional Chinese medicine makes it attractive for clinical development.

Inhibition of STAT3-DNA binding

Metal complexes and small molecules

Novel platinum compounds, CPA-1 and CPA-7, are considered analogs of cisplatin and preferentially interfere with STAT3 and disrupt its ability to bind to DNA [61]. This was shown to occur in vitro, in mouse fibroblast cells, and in various cell lines including breast, prostate, melanoma, and colon tumor cells. The most potent compound, CPA-7, also induced tumor regression in a murine colon cancer model. This molecule was also active in murine glioma models, inhibiting STAT3 activity and tumor growth and downregulating IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine [128]. However, Assi et al. showed that CPA-7 elicited effects on peripheral glioma cell lines but not intracranial cells, suggesting that this molecule is unable to penetrate the central nervous system [71] and that further drug development is not warranted.

STX-0119, an N-[2-(1,3,4-oxadiazolyl)]-4-quinolinecarboxa mide derivative, selectively blocked DNA binding activity of STAT3, suggesting the mechanism of binding to either the SH2 or DNA binding domains [129]. This molecule suppressed the expression of various STAT3 target proteins, including c-myc, cyclin D1, and Bcl-xL and the growth of many cancer cell lines [130]. An oral agent, STX-0119 was found to abrogate the growth of a lymphoma xenograft model, suppressing levels of c-myc, Ki-67, and pSTAT3 within the tumors. These studies were also extended to glioblastoma multiforme stem-like cells (GBM-SC) derived from patient with recurrent GBM tumors where again target gene expression of STAT3 was strongly inhibited [131].

A curcumin analogue, FLLL32, was developed with special biochemical properties for more specificity for STAT3 [132]. This compound decreased STAT3 binding to DNA and cell proliferation in canine and human osteosarcoma cells with decreased levels of both total and pSTAT3. FLLL32 also downregulated pSTAT3 in head and neck squamous cell cancer lines, inducing a potent anti-tumor effect and increased the proportion of apoptotic cells [133].

STAT3 oligonucleotides

Transcription factor decoys consist of nucleotide sequences derived from conserved genomic regulatory elements that are recognized and bound by the transcription factor being targeted. Decoys elicit their biological effects by competitively inhibiting binding of the endogenous transcription factor to corresponding cis elements in genomic DNA, thus preventing expression of target genes. Various oligonucleotide molecules have been developed and studied. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short sequences of nucleotides developed to alter downstream protein expression [134]. STAT3 oligonucleotide decoy was derived from the conserved hSIE genomic element found in the c-fos gene promoter, and was comprised of a 15-bp duplex oligonucleotide with free ends and phosphorothioate modifications of the three 5′ and 3′ nucleotides. It binds specifically to pSTAT3 and blocks its binding to DNA, resulting in inhibition of transcription and potentially tumor cell proliferation [135].

Studies in preclinical models of many human cancers have demonstrated antitumor efficacy of this STAT3 decoy [136–141]. A phase 0 clinical trial of 30 HNSCC patients undergoing surgical resection demonstrated significant downregulation of STAT3 target gene expression in the tumors that received the intratumoral injection of decoy compared with saline controls [135]. The “parent” STAT3 decoy oligonucleotide used in the phase 0 trial is limited by relatively rapid thermal and enzymatic degradation upon systemic administration, thereby limiting broad clinical translation. The parent STAT3 decoy has been modified by adding carbon spacers on both ends creating a cyclic STAT3 decoy, which is resistant to thermal degradation and is stable in serum for up to 12 h.

Further investigation demonstrated antitumor efficacy in HNSCC xenograft models with intravenous administration [135,142]. Toxicology studies demonstrated no evidence of organ hematopoietic toxicity, and tumor growth inhibition was accompanied by downregulation of STAT3 target gene expression in the tumors [142,143]. Currently, the cyclic STAT3 decoy is being developed for a proposed phase I clinical trial and will be a first-in human model.

Decreasing total STAT3 expression

A final target in the STAT3 pathway is the quantitative reduction in STAT3 expression by inhibition of mRNA. ISIS 481464 (AZD9150) is a synthetic ASO that is complementary to mRNA for STAT3 and demonstrated antiproliferative effects in various xenograft models resulting in reduction of STAT3 mRNA and protein in preclinical monkey and mouse models [144]. In a first-in-human phase I trial in patients with advanced cancers, this ASO was well-tolerated and shown to have anti-tumor activity in patients with lymphoma [145]; a dose-expansion phase II trial in lymphoma is ongoing (NCT01563302). Other active clinical trials studying ISIS 481464 (AZD9150) include phase II studies in patients with malignant ascites (NCT02417753) and metastatic HNSCC (monotherapy or in combination with MEDI4736, NCT02499328). A phase I trial in patients with advanced or metastatic HCC has been completed; results are not yet reported (NCT01839604).

Conclusions

The STAT3 pathway involves complex interactions between cell surface receptors, cytokine signaling, and non-receptor tyrosine kinases, and ultimately directs aberrant protein synthesis, growth, and survival. Although hyperactivation of the STAT3 transcription factor is a hallmark of HNSCC, oncogenic mutations are not described. Rather, aberrant signaling is associated with activation by upstream growth factor receptors and a loss of function of selective PTPRs that de-phosphorylate pSTAT3. Due to the association of STAT3 with oncogenic behavior and resistance to standard therapeutics in HNSCC, it remains a compelling target. Identification of predictive biomarkers for STAT3 dependence is essential, as STAT3-targeting drugs can be associated with hematologic toxicity, in some cases leading to early termination of trials. Balancing toxicity with benefit remains a challenge, especially in the recurrent/metastatic setting, where palliation of symptoms is of utmost importance. Predictive biomarkers for STAT3 dependence could lead to clinical responses to lower doses of STAT3-targeting drugs, thereby also leading to lower treatment-related toxicities. Although no direct STAT3 inhibitor has reached FDA approval, due to inherent challenges in targeting transcription factors, the field is poised for breakthroughs. Promising targets include STAT3 mRNA translation, upstream cell surface receptors, the SH2 domain of STAT3, and binding of the STAT3 dimer to DNA. Ongoing, early phase clinical trials may lead to efficacy studies in HNSCC and other malignancies, ultimately filling a major gap in our therapeutic arsenal against human cancer.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, et al. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and - unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi AK, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leeman RJ, Lui VW, Grandis JR. STAT3 as a therapeutic target in head and neck cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6(3):231–41. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla S, et al. Aberrant expression and constitutive activation of STAT3 in cervical carcinogenesis: implications in high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:282. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grandis JR, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling abrogates apoptosis in squamous cell carcinogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(8):4227–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaykalova DA, et al. NF-kappaB and stat3 transcription factor signatures differentiate HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(8):1879–89. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bromberg JF, et al. Stat3 activation is required for cellular transformation by v-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(5):2553–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkson J, et al. Stat3 activation by Src induces specific gene regulation and is required for cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(5):2545–52. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yue P, Turkson J. Targeting STAT3 in cancer: how successful are we? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(1):45–56. doi: 10.1517/13543780802565791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandis JR, et al. Requirement of Stat3 but not Stat1 activation for epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated cell growth In vitro. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(7):1385–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kijima T, et al. STAT3 activation abrogates growth factor dependence and contributes to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumor growth in vivo. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13(8):355–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sen M, et al. Targeting Stat3 abrogates EGFR inhibitor resistance in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(18):4986–96. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masuda M, et al. Constitutive activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 correlates with cyclin D1 overexpression and may provide a novel prognostic marker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T, et al. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):48–54. doi: 10.1038/nm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kortylewski M, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11(12):1314–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta S, et al. Inhibition of NK cell activity through TGF-beta 1 by downregulation of NKG2D in a murine model of head and neck cancer. J Immunol. 2005;175(8):5541–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JC, et al. Elevated TGF-beta1 secretion and down-modulation of NKG2D underlies impaired NK cytotoxicity in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2004;172(12):7335–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albesiano E, et al. Immunologic consequences of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation in human squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70(16):6467–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, et al. Clinical impact of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, epidermal growth factor receptor, p53, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 expression in resected adenocarcinoma of lung by using tissue microarray. Cancer. 2010;116(3):676–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindler C, Darnell JE., Jr Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: the JAK-STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:621–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao X, et al. Activation and association of Stat3 with Src in v-Src-transformed cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(4):1595–603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzzo C, Che Mat NF, Gee K. Interleukin-27 induces a STAT1/3- and NF-kappaB-dependent proinflammatory cytokine profile in human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(32):24404–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.112599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stransky N, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333(6046):1157–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agrawal N, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333(6046):1154–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo HW, et al. Constitutively activated STAT3 frequently coexpresses with epidermal growth factor receptor in high-grade gliomas and targeting STAT3 sensitizes them to Iressa and alkylators. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(19):6042–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julien SG, et al. Inside the human cancer tyrosine phosphatome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(1):35–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, et al. Identification of STAT3 as a substrate of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(10):4060–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veeriah S, et al. The tyrosine phosphatase PTPRD is a tumor suppressor that is frequently inactivated and mutated in glioblastoma and other human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(23):9435–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900571106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lui VW, et al. Frequent mutation of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases provides a mechanism for STAT3 hyperactivation in head and neck cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(3):1114–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319551111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peyser ND, et al. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of PTPRT increases STAT3 activation and sensitivity to STAT3 inhibition in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peyser ND, et al. Loss-of-function PTPRD mutations lead to increased STAT3 activation and sensitivity to STAT3 inhibition in head and neck cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz D, Ito E, Liu FF. On the path to seeking novel radiosensitizers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(4):988–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seiwert TY, Salama JK, Vokes EE. The concurrent chemoradiation paradigm–general principles. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(2):86–100. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birner P, et al. STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation influences survival in glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2010;100(3):339–43. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao L, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 and ErbB2 suppresses tumor growth, enhances radiosensitivity, and induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in glioma cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(4):1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brantley EC, Benveniste EN. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3: a molecular hub for signaling pathways in gliomas. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(5):675–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman T, et al. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2474–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia R, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 in fibroblasts transformed by diverse oncoproteins and in breast carcinoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8(12):1267–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page C, et al. Elevated phosphorylation of AKT and Stat3 in prostate, breast, and cervical cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2000;17(1):23–8. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson CJ, Miller WR. Elevated levels of members of the STAT family of transcription factors in breast carcinoma nuclear extracts. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(4):840–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham D, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1030–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauer R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1731–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(15):3579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung CH, et al. Integrating epidermal growth factor receptor assay with clinical parameters improves risk classification for relapse and survival in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung CH, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number is associated with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4170–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haura EB, et al. A pilot study of preoperative gefitinib for early-stage lung cancer to assess intratumor drug concentration and pathways mediating primary resistance. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(11):1806–14. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f38f70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boehm AL, et al. Combined targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor, signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, and Bcl-X(L) enhances antitumor effects in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(6):1632–42. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(11):798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston PA, Grandis JR. STAT3 signaling: anticancer strategies and challenges. Mol Interv. 2011;11(1):18–26. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harrison C, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kremer JM, et al. The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP-690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):1895–905. doi: 10.1002/art.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papp KA, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two, randomised, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bjd.14018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tefferi A, Pardanani A. JAK inhibitors in myeloproliferative neoplasms: rationale, current data and perspective. Blood Rev. 2011;25(5):229–37. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghoreschi K, et al. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550) J Immunol. 2011;186(7):4234–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hedvat M, et al. The JAK2 inhibitor AZD1480 potently blocks Stat3 signaling and oncogenesis in solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(6):487–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xin H, et al. Antiangiogenic and antimetastatic activity of JAK inhibitor AZD1480. Cancer Res. 2011;71(21):6601–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sen M, et al. JAK kinase inhibition abrogates STAT3 activation and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumor growth. Neoplasia. 2015;17(3):256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turkson J, et al. Inhibition of constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation by novel platinum complexes with potent antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(12):1533–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tefferi A. JAK inhibitors for myeloproliferative neoplasms: clarifying facts from myths. Blood. 2012;119(12):2721–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-395228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hurwitz H, et al. JANUS 1: a phase 3, placebo-controlled study of ruxolitinib plus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPC) after failure or intolerance of first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (suppl; asbtr TPS4147) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cutolo M. The kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: latest findings and clinical potential. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5(1):3–11. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12470753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plimack ER, et al. AZD1480: a phase I study of a novel JAK2 inhibitor in solid tumors. Oncologist. 2013;18(7):819–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pardanani A, et al. Safety and efficacy of fedratinib in patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang M, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and tolerability of the oral JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib (SAR302503) in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(4):415–21. doi: 10.1002/jcph.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pardanani A, et al. Safety and efficacy of TG101348, a selective JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):789–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwamaru A, et al. A novel inhibitor of the STAT3 pathway induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2007;26(17):2435–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kong LY, et al. A novel inhibitor of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation is efficacious against established central nervous system melanoma and inhibits regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5759–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Assi HH, et al. Preclinical characterization of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 small molecule inhibitors for primary and metastatic brain cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349(3):458–69. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.214619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, et al. Small-molecule STAT3 signaling pathway modulators from Polygonum cuspidatum. Planta Med. 2012;78(14):1568–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuang S, et al. 2-Methoxystypandrone inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by inhibiting Janus kinase 2 and IkappaB kinase. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(4):473–80. doi: 10.1111/cas.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allen C, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB-related serum factors as longitudinal biomarkers of response and survival in advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(11):3182–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heinrich PC, et al. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374(Pt 1):1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emery P, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1516–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smolen JS, et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):987–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yokota S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):998–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sieper J, et al. Assessment of short-term symptomatic efficacy of tocilizumab in ankylosing spondylitis: results of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):95–100. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Illei GG, et al. Tocilizumab in systemic lupus erythematosus: data on safety, preliminary efficacy, and impact on circulating plasma cells from an open-label phase I dosage-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):542–52. doi: 10.1002/art.27221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayer CL, et al. Dose selection of siltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75(5):1037–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dorff TB, et al. Clinical and correlative results of SWOG S0354: a phase II trial of CNTO328 (siltuximab), a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6, in chemotherapy-pretreated patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(11):3028–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fizazi K, et al. Randomised phase II study of siltuximab (CNTO 328), an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody, in combination with mitoxantrone/prednisone versus mitoxantrone/prednisone alone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garcia-Manero G, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing siltuximab plus best supportive care (BSC) with placebo plus BSC in anemic patients with International Prognostic Scoring System low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(9):E156–62. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rossi JF, et al. A phase I/II study of siltuximab (CNTO 328), an anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, in metastatic renal cell cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(8):1154–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prasad S, et al. Targeting inflammatory pathways by flavonoids for prevention and treatment of cancer. Planta Med. 2010;76(11):1044–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lamson DW, Brignall MS. Antioxidants and cancer, part 3: quercetin. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(3):196–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Michaud-Levesque J, Bousquet-Gagnon N, Beliveau R. Quercetin abrogates IL-6/STAT3 signaling and inhibits glioblastoma cell line growth and migration. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318(8):925–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Senggunprai L, et al. Quercetin and EGCG exhibit chemopreventive effects in cholangiocarcinoma cells via suppression of JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 2014;28(6):841–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Muthian G, Bright JJ. Quercetin, a flavonoid phytoestrogen, ameliorates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-12 signaling through JAK-STAT pathway in T lymphocyte. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24(5):542–52. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCI.0000040925.55682.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cao HH, et al. Quercetin exerts anti-melanoma activities and inhibits STAT3 signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87(3):424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayashi A, Gillen AC, Lott JR. Effects of daily oral administration of quercetin chalcone and modified citrus pectin on implanted colon-25 tumor growth in Balb-c mice. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(6):546–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mukherjee A, Khuda-Bukhsh AR. Quercetin down-regulates IL-6/STAT-3 signals to induce mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in a nonsmall-cell lung-cancer cell line, A549. J Pharmacopuncture. 2015;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2015.18.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hatcher H, et al. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(11):1631–52. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mancuso C, Barone E. Curcumin in clinical practice. Myth or reality? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(7):333–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(2):141–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim HY, et al. Curcumin suppresses Janus kinase-STAT inflammatory signaling through activation of Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 in brain microglia. J Immunol. 2003;171(11):6072–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Natarajan C, Bright JJ. Curcumin inhibits experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-12 signaling through Janus kinase-STAT pathway in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168(12):6506–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bharti AC, Donato N, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits constitutive and IL-6-inducible STAT3 phosphorylation in human multiple myeloma cells. J Immunol. 2003;171(7):3863–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weissenberger J, et al. Dietary curcumin attenuates glioma growth in a syngeneic mouse model by inhibition of the JAK1,2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(23):5781–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saydmohammed M, Joseph D, Syed V. Curcumin suppresses constitutive activation of STAT-3 by up-regulating protein inhibitor of activated STAT-3 (PIAS-3) in ovarian and endometrial cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110(2):447–56. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhen L, et al. Curcumin inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma proliferation and invasion via EGFR signaling pathways. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(10):6438–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chakravarti N, Myers JN, Aggarwal BB. Targeting constitutive and interleukin-6-inducible signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) Int J Cancer. 2006;119(6):1268–75. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Song H, et al. A low-molecular-weight compound discovered through virtual database screening inhibits Stat3 function in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(13):4700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409894102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miyoshi K, et al. Stat3 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of psoriasis: a clinical feasibility study with STA-21, a Stat3 inhibitor. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(1):108–17. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Han Y, et al. Loss of SHP1 enhances JAK3/STAT3 signaling and decreases proteosome degradation of JAK3 and NPM-ALK in ALK+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2006;108(8):2796–803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Witkiewicz A, et al. Loss of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase expression correlates with the advanced stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2007;38(3):462–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen KF, et al. A novel obatoclax derivative, SC-2001, induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through SHP-1-dependent STAT3 inactivation. Cancer Lett. 2012;321(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Su JC, et al. SC-2001 overcomes STAT3-mediated sorafenib resistance through RFX-1/SHP-1 activation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2014;16(7):595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wong AL, et al. Phase I and biomarker study of OPB-51602, a novel signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 inhibitor, in patients with refractory solid malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):998–1005. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ogura M, et al. Phase I study of OPB-51602, an oral inhibitor of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, in patients with relapsed/refractory hematological malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(7):896–901. doi: 10.1111/cas.12683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brambilla L, et al. Hitting the right spot: mechanism of action of OPB-31121, a novel and potent inhibitor of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) Mol Oncol. 2015;9(6):1194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hayakawa F, et al. A novel STAT inhibitor, OPB-31121, has a significant antitumor effect on leukemia with STAT-addictive oncokinases. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e166. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bendell JC, et al. Phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation, and pharmacokinetic study of STAT3 inhibitor OPB-31121 in subjects with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(1):125–30. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Takakura A, et al. Pyrimethamine inhibits adult polycystic kidney disease by modulating STAT signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(21):4143–54. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Becker S, Groner B, Muller CW. Three-dimensional structure of the Stat3beta homodimer bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;394(6689):145–51. doi: 10.1038/28101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Turkson J, et al. Phosphotyrosyl peptides block Stat3-mediated DNA binding activity, gene regulation, and cell transformation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):45443–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Turkson J, et al. Novel peptidomimetic inhibitors of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 dimerization and biological activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(3):261–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Siddiquee KA, et al. An oxazole-based small-molecule Stat3 inhibitor modulates Stat3 stability and processing and induces antitumor cell effects. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2(12):787–98. doi: 10.1021/cb7001973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Watkins B, et al. Attenuation of radiation- and chemoradiation-induced mucositis using gamma-D-glutamyl-L-tryptophan (SCV-07) Oral Dis. 2010;16(7):655–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Alterovitz G, et al. Personalized medicine for mucositis: bayesian networks identify unique gene clusters which predict the response to gamma-D-glutamyl-L-tryptophan (SCV-07) for the attenuation of chemoradiation-induced oral mucositis. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(10):951–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mandal PK, et al. Potent and selective phosphopeptide mimetic prodrugs targeted to the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. J Med Chem. 2011;54(10):3549–63. doi: 10.1021/jm2000882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Auzenne EJ, et al. A phosphopeptide mimetic prodrug targeting the SH2 domain of Stat3 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2012;10(2):155–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McMurray JS, et al. The consequences of selective inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) tyrosine705 phosphorylation by phosphopeptide mimetic prodrugs targeting the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain. JAKSTAT. 2012;1(4):263–347. doi: 10.4161/jkst.22682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang Y, et al. Tanshinones: sources, pharmacokinetics and anti-cancer activities. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(10):13621–66. doi: 10.3390/ijms131013621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shin DS, et al. Cryptotanshinone inhibits constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 function through blocking the dimerization in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):193–202. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lu L, et al. Cryptotanshinone inhibits human glioma cell proliferation by suppressing STAT3 signaling. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;381(1–2):273–82. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1711-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhang L, et al. Stat3 inhibition activates tumor macrophages and abrogates glioma growth in mice. Glia. 2009;57(13):1458–67. doi: 10.1002/glia.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Matsuno K, et al. Identification of a new series of STAT3 inhibitors by virtual screening. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1(8):371–5. doi: 10.1021/ml1000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ashizawa T, et al. Antitumor activity of a novel small molecule STAT3 inhibitor against a human lymphoma cell line with high STAT3 activation. Int J Oncol. 2011;38(5):1245–52. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ashizawa T, et al. Effect of the STAT3 inhibitor STX-0119 on the proliferation of cancer stem-like cells derived from recurrent glioblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2013;43(1):219–27. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fossey SL, et al. The novel curcumin analog FLLL32 decreases STAT3 DNA binding activity and expression, and induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Abuzeid WM, et al. Sensitization of head and neck cancer to cisplatin through the use of a novel curcumin analog. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(5):499–507. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Crooke ST, et al. Mechanisms of antisense drug action; antisense drug technology, principles, strategies and applications, an introduction. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2007. pp. 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sen M, et al. First-in-human trial of a STAT3 decoy oligonucleotide in head and neck tumors: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(8):694–705. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Leong PL, et al. Targeted inhibition of Stat3 with a decoy oligonucleotide abrogates head and neck cancer cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):4138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0534764100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chan KS, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(5):720–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Xi S, Gooding WE, Grandis JR. In vivo antitumor efficacy of STAT3 blockade using a transcription factor decoy approach: implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2005;24(6):970–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhang X, et al. Therapeutic effects of STAT3 decoy oligodeoxynucleotide on human lung cancer in xenograft mice. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sun X, et al. Growth inhibition of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by blocking STAT3 activation with decoy-ODN. Cancer Lett. 2008;262(2):201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gu J, et al. Blockage of the STAT3 signaling pathway with a decoy oligonucleotide suppresses growth of human malignant glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2008;89(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Paul M, Sen Majumder S, Bhadra A. Selfish mothers? An empirical test of parent-offspring conflict over extended parental care. Behav Processes. 2014;103:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Leibowitz MS, et al. Deficiency of activated STAT1 in head and neck cancer cells mediates TAP1-dependent escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(4):525–35. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0961-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Burel SA, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the toxicological effects of a novel constrained ethyl modified antisense compound targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in mice and cynomolgus monkeys. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013;23(3):213–27. doi: 10.1089/nat.2013.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hong DS, et al. A phase I study of ISIS 481484 (AZD9150), a first-in-human, first-in-class, antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of STAT3, inpatients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013:31. (suppl; abstr 8523) [Google Scholar]