Abstract

Background:

Gallstones have become a major health problem because of their silent manifestation and unclear pathogenesis. Although the association between the disturbed lipid metabolism and formation of gallstones has been elucidated in many studies, the effect of cholecystectomy on lipid profile has not been studied in detail.

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to study the effect of cholecystectomy on lipid levels in patients with gallstones.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted on 50 patients with gallstones and 30 healthy volunteers for comparison of lipid levels. Subsequently, cholecystectomy was conducted on patients with gallstones and pre- and post-operative lipid levels were compared.

Results:

There was a significant decrease in total cholesterol, and triglycerides levels and increase in high-density lipoprotein levels after 1 month of surgery, while low-density lipoprotein levels and very low-density lipoprotein were not statistically changed.

Conclusion:

Cholecystectomy can significantly improve lipid levels in patients with gallstones.

Keywords: Cholecystectomy, cholelithiasis, cholesterol, lipids

Introduction

Gallstone disease is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases with worldwide distribution and with a substantial burden to health-care delivery system.[1,2] Gallstone disease is a chronic recurrent hepatobiliary disease, which may result from impaired metabolism of cholesterol, bilirubin and bile acid (BA), and is characterized by the formation of the gallstone in hepatic bile duct, common bile duct or gallbladder.[3] Many studies have shown an association between gallstones and abnormal lipids.

Most of the gallstones patients present with severe abdominal pain requiring investigations and treatment. Many of them need surgical intervention by the time they are symptomatic.[4] If the gallbladder is removed, the bile in the liver will directly enter the upper part of the intestine. As a result, BA circulate faster, thus exposing the enterohepatic system to a greater BA flux. Lipid and BA metabolisms are functionally interrelated.[5]

Even though lipid and BA metabolisms are functionally related, how gallbladder removal affects lipids is not well understood. Therefore, the current study was planned with a goal to determine the difference in the serum lipid levels in patients with gallstones compared to normal healthy individuals and study the changes in serum lipid levels in patients after cholecystectomy.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried in the Department of Surgery and Department of Biochemistry in a tertiary care center attached to a medical college, prospectively from July 2014 to June 2016. The study was approved by Institutional Research and Ethical Committee.

Fifty patients in the age group of 20–70 years, of both sexes, who presented with acute abdominal pain, with a high degree of suspicion of biliary calculi and thirty healthy age-matched individuals with no present or history of cholelithiasis were enrolled for the study. The confirmation of cholelithiasis and its complications was done by ultrasonography (USG). Patients with intrahepatic calculi, not undergoing cholecystectomy, patients on antilipidemic drugs or patients with renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, pancreatitis, cardiac failure, morbid obesity, hypothyroidism, sickle cell disease, hemoglobinopathies, and pregnancy were excluded from the study. The patient group and control group were labeled A and B, respectively. A detailed history to assess the various risk factors was taken, with particular attention to the hepatobiliary system. Each patient was examined physically to assess the general condition, and the vital data were recorded. Per abdominal examination was done according to the standard protocol and the findings were documented. Based on the severity of the signs and symptoms and the USG reports, the treatment modality was decided. Patients who presented with acute pain abdomen, rigidity and obstructive symptoms with cholelithiasis were managed with intravenous fluids and Ryle's tube aspiration. After taking the written informed patient's consent, they were taken up for surgery.

Two milliliters of fasting blood samples were obtained before surgical intervention and after surgery 1 week and 1 month in Group A by venipuncture under all aseptic conditions, while in Group B blood samples were collected at one time. Samples were allowed to clot at room temperature. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 3500 ×g for 10 min. The separated serum samples were immediately processed for biochemical estimations or stored at −20°C for further use.

Gallstones were collected after cholecystectomy and further divided into three categories depending on their shape, size, and texture; pale yellow and whitish stones-the cholesterol calculi; black and blackish brown-the pigment calculi and brownish yellow; or greenish with laminated features-mixed calculi. The various physical parameters of stones such as number, shape, size, texture, and cross-section were noted.

Serum lipid parameters such as serum total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and serum triglycerides (TGs) were estimated on AIA-360, fully automatic analyzer Tosoh, Japan with kits from Alere, Tosoh, Japan. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using Friedwald's formula after taking into consideration its limitation, LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + [TG/5]). Very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) was calculated by TG/5.

The stones were washed by distilled water and dried; then they were powdered in a pestle and mortar to detect the organic and inorganic compounds such as cholesterol, phosphates, calcium, bilirubin, oxalates, and carbonates.

All statistical analyses were performed using Excel spreadsheets. The results of laboratory tests in the study and control groups were summarized as mean ± standard deviation. Comparison between subjects (both participating groups) was done using Student's unpaired t-test. 95% confidence interval was taken into consideration and P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Group A consisted of 32 females and 18 males with female to male ratio of 1.7:1, while Group B had 18 females and 12 males with ratio of 1.5:1. The average body mass index of patients in both the groups was 27.45 and 25.66 kg/m2 respectively.

The biochemical analysis of stones revealed that maximum stones were cholesterol stones (36, 72%) followed by mixed (8, 16%) and pigment stones (6, 12%). 82% (41) of patients presented with multiple stone, while in only 18% solitary stones were present.

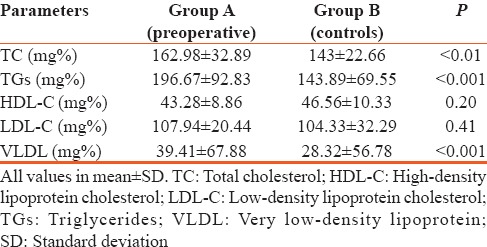

The mean of serum lipids of controls and in patients taken before surgery is shown in Table 1. The mean levels of TC, TGs, and VLDL-C were observed to be significantly elevated in patients with cholelithiasis as compared to controls. The mean levels of LDL-C were although higher in patients, but the rise was not statistically significant. Similarly, the mean levels of HDL-C were lower in patients, but the decrease was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Serum lipid profile in Groups A and B

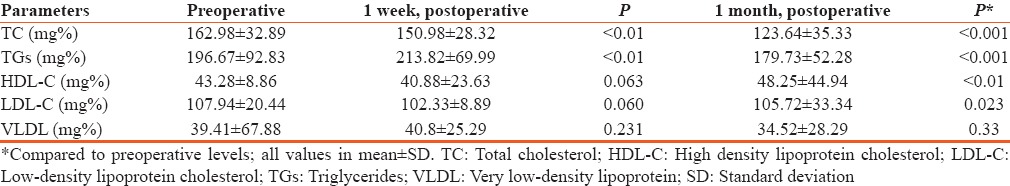

The mean levels of serum lipid levels of Group A preoperative, postoperative (1 week and 1 month after surgery) are shown in Table 2. The decrease in mean levels of serum cholesterol was significant after 1 week of surgery and highly significant after 1 month of surgery. There was a significant increase in serum TGs after 1 week of surgery, but after 1 month they reverted back to normal, and this decrease was highly significant. The serum HDL-C slightly decrease after 1 week of surgery, but it significantly increased after 1 month of surgery, however, no significant difference was observed in LDL-C and VLDL-C after 1 week and 1 month of surgery.

Table 2.

Serum lipid profile in Group A preoperative, 1 week and 1 month postoperative

Discussion

Around half of the patients of cholilithiasis have abnormal lipid profile. This increases the incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke.[6,7,8,9] Recent studies have shown that hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, and low level of HDL-C are commonly associated with cholilithiasis.[10,11] It is a well-known fact that this association can further lead to CAD and stroke.[12,13,14] In the present study, the mean levels of TC, TGs, and VLDL-C were significantly elevated in patients with cholelithiasis as compared to controls, while there was the insignificant difference for LDL-C and HDL-C levels.

In the present study, there was a significant decrease in levels of TC after one week of surgery and after 1 month of surgery. Similarly, TGs levels after 1 month of surgery were significantly decreased. Other studies have shown similar results.[15,16] In the present study, the serum HDL-C slightly decrease after 1 week of surgery, but it significantly increased after 1 month of surgery. This effect is in contrast to the study conducted by Malik et al.,[17] who reported no change on HDL-C levels after 6 months of surgery.

From the study, it can be concluded that cholecystectomy leads to normalization of lipid levels and thus can be helpful in blocking the subsequent development of CAD and stroke.

Limitations of the study

Patients were on medications postoperatively, and effect of medications was not checked. This can be a confounding as well as a limitation in the study. At the same time, no distinction was made between open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, again a limitation of the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–11. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aerts R, Penninckx F. The burden of gallstone disease in Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(Suppl 3):49–53. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-0673.2003.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belousov Yu V. Up-to-date guide. Moscow: Exma; 2006. Pediatric gastroenterology; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaraari AM, Jagannadharao P, Patil TN, Hai A, Awamy HA, El Saeity SO, et al. Quantitative analysis of gallstones in Libyan patients. [Last cited on 2017 Jun 06];Libyan J Med. 2010 5 doi: 10.4176/091020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3066788/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amigo L, Husche C, Zanlungo S, Lütjohann D, Arrese M, Miquel JF, et al. Cholecystectomy increases hepatic triglyceride content and very-low-density lipoproteins production in mice. Liver Int. 2011;31:52–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson S, Wilhelmsen L, Lappas G, Rosengren A. High lipid levels and coronary disease in women in Göteborg – outcome and secular trends: A prospective 19 year follow-up in the BEDA study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:704–16. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh BK, Mehta JL. Management of dyslipidemia in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002;17:503–11. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hachinski V, Graffagnino C, Beaudry M, Bernier G, Buck C, Donner A, et al. Lipids and stroke: A paradox resolved. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:303–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550040031011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson TA, Miller M, Schaefer EJ. Hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular risk reduction. Clin Ther. 2007;29:763–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurtul N, Pençe S, Kocoglu H, Aksoy H, Capan Y. Serum lipid and lipoproteins in gallstone patients. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2002;45:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Völzke H, Baumeister SE, Alte D, Hoffmann W, Schwahn C, Simon P, et al. Independent risk factors for gallstone formation in a region with high cholelithiasis prevalence. Digestion. 2005;71:97–105. doi: 10.1159/000084525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitchett DH, Leiter LA, Goodman SG, Langer A. Lower is better: Implications of the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study for Canadian patients. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:835–9. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298:299–308. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Maroni J, Szarek M, Grundy SM, et al. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1301–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Micheal J, Walmsley J, Schofield PF. Serial serum cholesterol estimation after biliary tract surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;57:829–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800571109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juvonen T, Kervinen K, Kairaluoma MI, Kesäniemi YA. Effect of cholecystectomy on plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik AA, Wani ML, Tak SI, Irshad I, Ul-Hassan N. Association of dyslipidaemia with cholilithiasis and effect of cholecystectomy on the same. Int J Surg. 2011;9:641–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]