Abstract

Context:

Infection caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) producing organism is a major problem regarding antibiotic resistance.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to find out the antibiogram of ESBL producing organisms isolated from various samples.

Settings and Design:

This cross-sectional study was carried out in the Department of Microbiology of a Tertiary Care Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh from January to June 2014.

Subjects and Methods:

One Hundred and seventy-nine ESBL producing Gram-negative organisms detected phenotypically by double-disc synergy test were enrolled in this study. Required data were collected from the records of the Microbiology laboratory.

Results:

ESBL production was detected in 16.07% (179/1114) of isolated organism. Of Escherichia coli, 15.75% were ESBL producers; 14.01% Pseudomonas spp., 36.84% Proteus spp., 18.57% Klebsiella spp., and 21.05% of Acinetobacter spp., were ESBL producers. Maximum (43.58%) ESBL producers were isolated from surgery departments, and wound swabs yielded majority (53%) of them. About 13% ESBL producers were isolated in outdoor patients mostly from community-acquired infections. Most ESBL producers were resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Carbapenems especially imipenem was the most effective drug showing excellent sensitivity; colistin and piperacillin/tazobactam also had better sensitivity result. Most of the ESBL producers showed a good sensitivity to amikacin, but all of them were highly resistant to ciprofloxacin.

Conclusions:

ESBL production should be detected routinely in all Microbiology laboratories. Infection control, rational use of antibiotics must be done promptly to prevent the development and spread of ESBL producing organisms.

Keywords: Antibiogram, Bangladesh, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases

Introduction

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) are enzymes that mediate resistance to extended spectrum, for example, third generation cephalosporins as well as monobactams.[1] Infections caused by ESBL producing organism represent a major problem, antibiotic resistance and is of great importance because of its clinical implication with higher mortality rate and health-care cost.[2,3]

ESBL is found in a variety of Enterobacteriaceae and other organisms including Pseudomonas species.[4] ESBL producing organisms were initially isolated from nosocomial infections but are now also from community-acquired infections.[5,6] Plasmid coding for ESBL enzymes may carry coresistance genes for other non-β-lactam antibiotics.[7] Carbapenems are considered to be the antibiotic of choice in infections caused by ESBL-producer.[8,9] Hospital acquired isolates are more resistant than community-acquired isolates.[10]

The prevalence and distribution of ESBL producers differ from country to country and from hospital to hospital.[11] A limited number of studies on the prevalence of ESBL in Bangladesh show a high rate of ESBL producers.[12,13] It is essential to report ESBL production along with the routine sensitivity reporting, which will help proper antibiotic selection.[14]

This study was performed to find out the antibiotic sensitivity pattern of ESBL producing organisms isolated from the various clinical specimens in a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh.

Subjects and Methods

This study was done in the Department of Microbiology of a tertiary care hospital, Dhaka from January 2014 to June 2014. Phenotypically detected 179 Gram-negative bacilli that were reported as ESBL producing isolates were included in this cross-sectional study. Data regarding the identity of the patient, referring departments, type of specimen, isolated organisms, and the culture sensitivity pattern was collected from the records of the microbiology laboratory using a predesigned data collection form.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Various specimens (wound swab, pus, blood, tracheal aspirate, body fluids, urine, sputum, high vaginal swab, etc.,) were processed for culture, and the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of the isolated organisms was determined by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method using commercially available antibiotic discs (Oxoid, UK).[15] The organisms were tested against different antibiotics and commonly used discs were amikacin (30 μg), amoxyclav (20 μg amoxycillin/10 μg clavulanic acid), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), colistin (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), meropenem (10 μg), and piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 μg). Zone of inhibition was recorded as “Sensitive” or “Resistant” according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline.[16]

Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases by double-disc diffusion synergy method

ESBL production in Gram-negative organism was detected by double-disc synergy test on Mueller-Hinton agar media as described by Jarlier et al. and following the CLSI guideline.[16,17]

Results

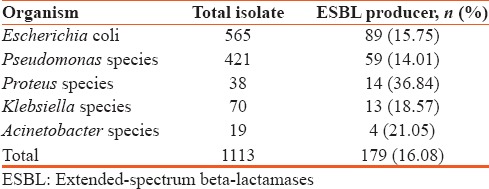

Among the isolated Gram-negative bacteria, 16.07% (179/1114) were ESBL producing organisms. Escherichia coli was the most commonly isolated ESBL producers, 15.75% of which produced ESBL; 14.01% of the isolated Pseudomonas spp., 36.84% Proteus spp., 18.57% Klebsiella spp., and 21.05% of isolated Acinetobacter spp., were ESBL producing organisms [Table 1].

Table 1.

Rate of isolation of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing gram negative organism

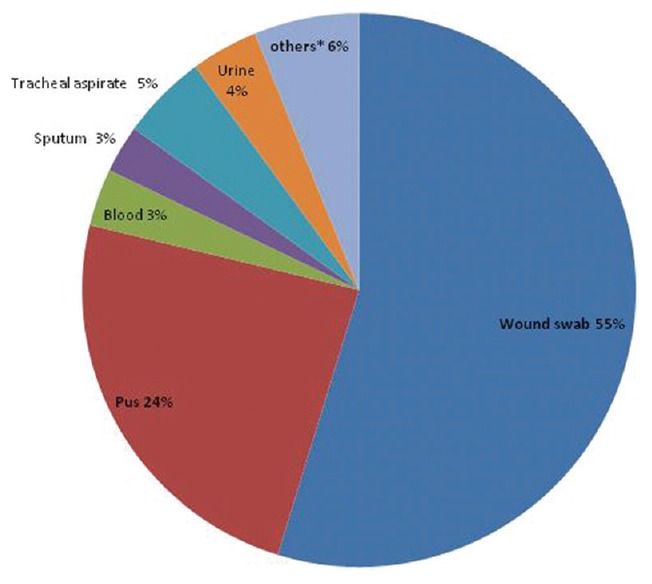

Maximum 54.75% of ESBL producing organisms were isolated from wound swab specimen followed by pus (24.02%). Others specimens that yielded the growth of ESBL producers were tracheal aspirate (5.03%), urine (3.91%), blood (3.35%), sputum (2.79%), and others (6.15%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Rate of isolation of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing bacteria from different clinical specimens (*others –high vaginal swab, ascitic fluid, pleural fluid, pus from liver abscess, bile, etc.)

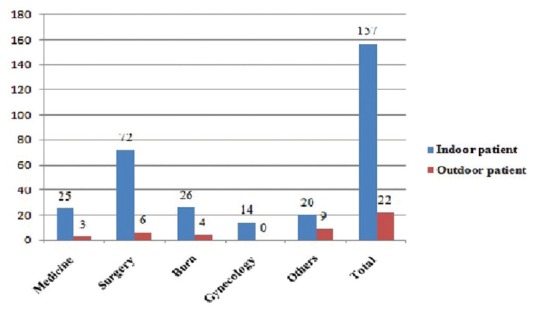

Highest ESBL producers (43.58%) were isolated from admitted patients of different surgery units which were followed by the National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery (16.76%). More than 87% ESBL producing bacteria were isolated from inpatient departments [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Pattern of distribution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing isolates in hospital and community

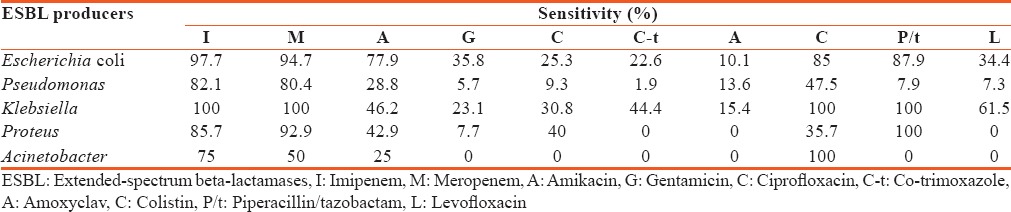

Carbapenems were the most effective antibiotics against E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and Pseudomonas spp.; colistin was found most efficacious against Acinetobacter spp. and Klebsiella spp. Piperacillin/tazobactam was the most effective antibiotic against Klebsiella spp. and Proteus spp. [Table 2].

Table 2.

Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing organisms

Discussion

The detection of ESBL-mediated resistance in microorganism is of paramount importance because of limited therapeutic options.[2] Although the prevalence of ESBL producer varies from country to country, it is more in Asia.[18] In Bangladesh, rate of ESBL producing bacteria isolated were 23% in 2008 and 24.85% in 2012.[12,19] In the present study, 16.07% of the Gram-negative organisms were detected as ESBL producer. The low rate of ESBL in the present study could be due to the inclusion of all indoor and outdoor patients' samples for study while previous studies were done on infected surgical wound, burn wound or ICU patients only.[12,19]

E. coli was the most commonly isolated organism in this study followed by Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp. In Bangladesh, the prevalence of ESBL producer among different organisms varied in different studies and the reported prevalence was higher than the present study.[12,13] The discrepancy of the isolation rate may be due to the varying prevalence of infection causing bacteria from area to area and even hospital to hospital. Different hospital deals with different types of disease and use different antibiotics.

Maximum ESBL producers were isolated from specimen of different surgery departments. The majority of the ESBL producing isolates were from inpatients which are in agreement with a study by Bindayna in Bahrain.[3] The reason might be due to the fact that drug-resistant gene that are carried by plasmid, are easy to transmit to other bacteria in hospital setting. The ESBL isolation of 13% from the outdoor patients, representing community-acquired infections, shows that ESBL producing organisms are not uncommon in the community and is in agreement with Helfand and Bonomo.[6]

Almost all types of specimen that were sent for culture yielded growth of ESBL producing organisms. The majority of them were isolated from wound swab and pus. This tertiary care hospital deals with a large number of patients including causality and surgical departments and also has the biggest burn unit in the country. This is the reason of huge number of wound swab and pus specimen that may also yielded the growth of maximum ESBL producers. Many of these patients were receiving long-time treatment and frequent antibiotic switch without culture sensitivity. Organisms may develop resistance during prolonged antimicrobial therapy, and initially susceptible bacteria may become resistant within few days after initiation of treatment.[16]

ESBL producing organisms usually show resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics as the genes encoding β-lactamases are often located on plasmids that also encode genes for resistance to other antibiotics.[20,21] ESBL producers were mostly resistant to antibiotics that are commonly used in Bangladesh. Carbapenems were the most efficacious drugs; imipenem and meropenem showed 80% to 100% sensitivity except against Acinetobacter spp. in this study, which is in accordance with findings of recent studies.[9,12] Although only few cases showed resistance this resistance to carbepenems is a matter of great concern in the treatment of infection.

The majority of the ESBL producers showed a comparatively good sensitivity to amikacin, and the pattern is consistent with other studies in Bangladesh.[9,12,22] The reason behind such low resistance might be the less use of this antibiotic in this hospital. The result indicates that amikacin may be considered as an alternative drug in infections caused by ESBL producers. Ciprofloxacin is a very important antibiotic, but all ESBL producers showed high resistance to it. This finding is consistent with studies who reported ESBL-producing organisms were highly resistant to ciprofloxacin.[9,12,22] The higher rate of resistance to ciprofloxacin might be due to the fact that this drug is used widely for many infections such as enteric fever which is endemic in Bangladesh.

Colistin and piperacillin/tazobactam showed good sensitivity in this study. All isolated Klebsiella and Acinetobacter spp. were sensitive to colistin, and except for Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp. piperacillin/tazobactam showed a good sensitivity to ESBL producers. These two injectable drugs are not usually used outside of hospital settings, and they are considered mainly as reserved drugs and are being used for those who are resistant to most other antibiotics.

There are very limited treatment options available for these pathogens. Hence, early detection and appropriate antibiotic application remain a significant priority in controlling the development and spread of ESBL producing organisms.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the Department of Microbiology, Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge to Prof. Dr. K. M. Shahidul Islam, Professor and Head of the Department of Microbiology of Dhaka Medical College for providing all the facilities.

References

- 1.CLSI. Twentieth Informational Supplement, CLSI Document M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2010. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: A clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bindayna KM, Senok AC, Jamsheer AE. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Bahrain. J Infect Public Health. 2009;2:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhary U, Aggarwal R. Extended spectrum-lactamases (ESBL)-An emerging threat to clinical therapeutics. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: An emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:159–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helfand MS, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli: Changing the therapy for hospital-acquired and community-acquired infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1415–6. doi: 10.1086/508891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacoby GA, Sutton L. Properties of plasmids responsible for production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:164–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitout JD. Infections with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Changing epidemiology and drug treatment choices. Drugs. 2010;70:313–33. doi: 10.2165/11533040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begum S, Salam MA, Alam KhF, Begum N, Hassan P, Haq JA. Detection of extended spectrum ß-lactamase in Pseudomonas spp. isolated from two tertiary care hospitals in Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shobha KL, Gowrish RS, Sugandhi R, Sreeja CK. Prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamases in urinary isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Citrobacter species and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pract Dr. 2007;3:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali AM. Frequency of Extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) producing nosocomial isolates in a tertiary care hospital in Rawalpindi. J R Army Med Corps. 2009;155:105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farzana R, Shamsuzzaman SM, Mamun KZ, Shears P. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing gram-negative bacteria isolated from wound and urine in a tertiary care hospital, Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2013;44:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haque R, Salam MA. Detection of ESBL producing nosocomial gram negative bacteria from a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26:887–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umadevi S, Kandhakumari G, Joseph NM, Kumar S, Easow JM, Stephen S, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5:236–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CLSI. Twenty-third Informational Supplement, CLSI Document M100-S23. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarlier V, Nicolas MH, Fournier G, Philippon A. Extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: Hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:867–78. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantón R, Novais A, Valverde A, Machado E, Peixe L, Baquero F, et al. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 1):144–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam MS, Yusuf MA, Begum SA, Sattar AF, Hossain A, Roy S. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Bacteriol Res. 2015;7:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denholm JT, Huysmans M, Spelman D. Community acquisition of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli: A growing concern. Med J Aust. 2009;190:45–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez F, Endimiani A, Hujer KM, Bonomo RA. The continuing challenge of ESBLs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:459–69. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarker JN, Bakar SM, Barua R, Sultana H, Anwar S, Saleh AA, et al. Susceptibility pattern of extended spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp. to Ciprofloxacin, amikacin and imipenem. J Sci Res Rep. 2015;8:1–9. [Google Scholar]