Abstract

Several cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors have been identified among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Gut-derived uremic toxins (GDUT) are important modifiable contributors in this respect. There are very few Indian studies on GDUT changes in CKD. One hundred and twenty patients older than 18 years diagnosed with CKD were enrolled along with forty healthy subjects. The patients were classified into three groups of forty patients based on stage of CKD. Indoxyl sulfate (IS), para cresyl sulfate (p-CS), indole acetic acid (IAA), and phenol were estimated along with the assessment of oxidative stress (OS), inflammatory state, and bone mineral disturbance. All the GDUT increased across the three groups of CKD. All patients had higher levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) as compared to controls. IS and IAA showed positive association with MDA/FRAP corrected for uric acid, whereas IS and p-CS showed positive association with IL-6. IS, IAA, and phenol showed a positive association with calcium × phosphorus product. GDUT increase OS and inflammatory state in CKD and may contribute to CVD risk.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease risk, chronic kidney disease, gut-derived uremic toxins

Introduction

Several cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors have been identified among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).[1] The presence of CKD itself has been identified as a CVD risk factor,[2] contributing to endothelial dysfunction. One feature responsible for this is accumulation of uremic toxins. Intestine is an important source of some uremic toxins. Apart from acting as a route for entry of uremic toxins, intestine undergoes changes in the composition of fermenting flora, leading to altered processing of uremic toxin precursors.[3] The gut-derived uremic toxins (GDUT) include endogenously produced molecules without interference by intestinal absorption (uric acid, xanthine), ingested exogenous toxins (advanced glycation end-products), and ingested exogenous products undergoing metabolic modification (derivatives of amino acids, phenol, and indoles). GDUT release inflammatory substances by leukocytes causing endothelial dysfunction.[4] Studying GDUT levels have come to focus with the development of strategies to modify intestinal absorption and metabolism of these toxins with the use of pre/probiotics, dietary modification, and adsorbent therapies. Available literature on GDUT is mostly from the western countries. The GDUT levels can also depend on serum albumin, ethnic variations, and dietary habits,[5] thereby indicating the need for Indian data. However, there are very few Indian studies.[6] Hence, the present study was taken up to estimate GDUT, namely, indoxyl sulfate (IS), para cresyl sulfate (p-CS), indole acetic acid (IAA), and phenol along with the role of GDUT on oxidative stress (OS), inflammation, and mineral metabolism in various stages of CKD in a South Indian cohort.

Material and Methods

The present study was conducted between September 2011 and December 2013 in the Department of Biochemistry, Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India. One hundred and twenty patients older than 18 years of age diagnosed to have CKD and willing to participate were enrolled along with forty healthy subjects. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The patients were classified into three groups of forty patients each (G1 = stages 1 and 2 or early CKD; G2 = stages 3 and 4 or advanced CKD; G3 = end-stage renal disease) based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated using Cockcroft-Gault formula.[7] Patients undergoing hemodialysis/peritoneal dialysis, those on antioxidant therapy or vitamin supplementation, taking pro/prebiotics, anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive drugs, and patients with active inflammatory disease or with abnormal liver function were excluded from the study.

Five milliliters of the peripheral venous blood was collected into heparinized bulb. Plasma was separated and was either analyzed immediately or stored at −80°C. GDUT were estimated using high-performance liquid chromatography with a fluorescence detector[8] using Schimadzu HPLC system (LC-20A, Kyoto, Japan). Serum deproteinization and bound uremic solutes displacement were done as part of sample pretreatment. Mobile phase A consisted of 2.76 g/L (20 mM) NaH2 PO4, H2O, and 1.85 g/L (5 mM) tetrabutylammonium iodide in water, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile. For elution, a 1.5 mL/min isocratic flow with 22:78 of A: B mobile phase was used. Twenty microliters of the sample was spiked, and quantification was done using fluorescence detection at specific excitation and emission wavelengths for individual molecules. The concentrations of uremic solutes were calculated using the standard calibration curves using fluorescence detector. The retention times were 4.8 min for phenol, 5.9 min for IAA, 12.5 min for IS, and 16.5 min for p-CS. Three samples spiked to study recovery showed 93% recovery in the normal range and 97% in the uremic range.

To study the effect of OS, malondialdehyde (MDA) and ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) were measured using spectrophotometric methods. The effect of inflammation was assessed by the measurement of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Nitric oxide (NO) levels were estimated to study the status of endothelial function. Calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) were estimated for assessing the mineral metabolism status. Urea and creatinine were estimated for assessing renal function. MDA, FRAP, and NO were estimated using spectrophotometric methods.[9,10,11] Urea, creatinine, Ca, P, and hsCRP were quantified using commercially available kits on Beckman Synchron autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA). IL-6 was estimated by ELISA using commercial kits on ChemWell analyzer (Awareness Technology, USA). A comprehensive score was calculated to have an estimate of the sum effect of GDUT on the pathophysiological factors for CVD risk studied. MDA/FRAP corrected for uric acid (FRAP_U), IL-6, and Ca × P product were included in the generation of the score. Values below or equal to control median level of each of the parameters were taken as no risk (score of 0), up to 25% above control median were given a score of 1, between 25% and 50% above control median were given a score of 2, and more than 50% above control median were given a score of 3.

Statistical analysis

Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to test the significance of difference in parameters studied. Data for uremic toxins were normalized by logarithmic transformation for regression analysis to study association between uremic toxins and CVD risk factors. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

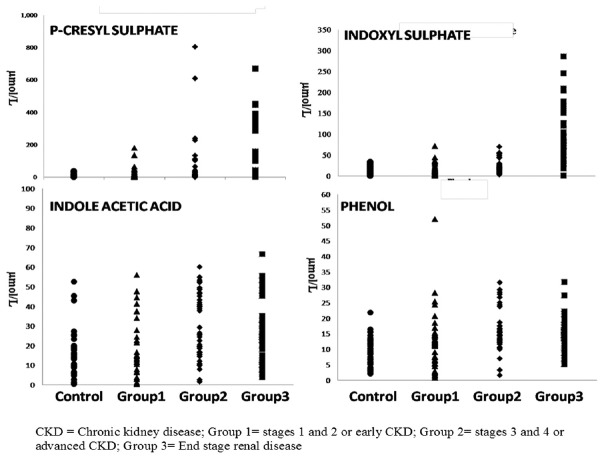

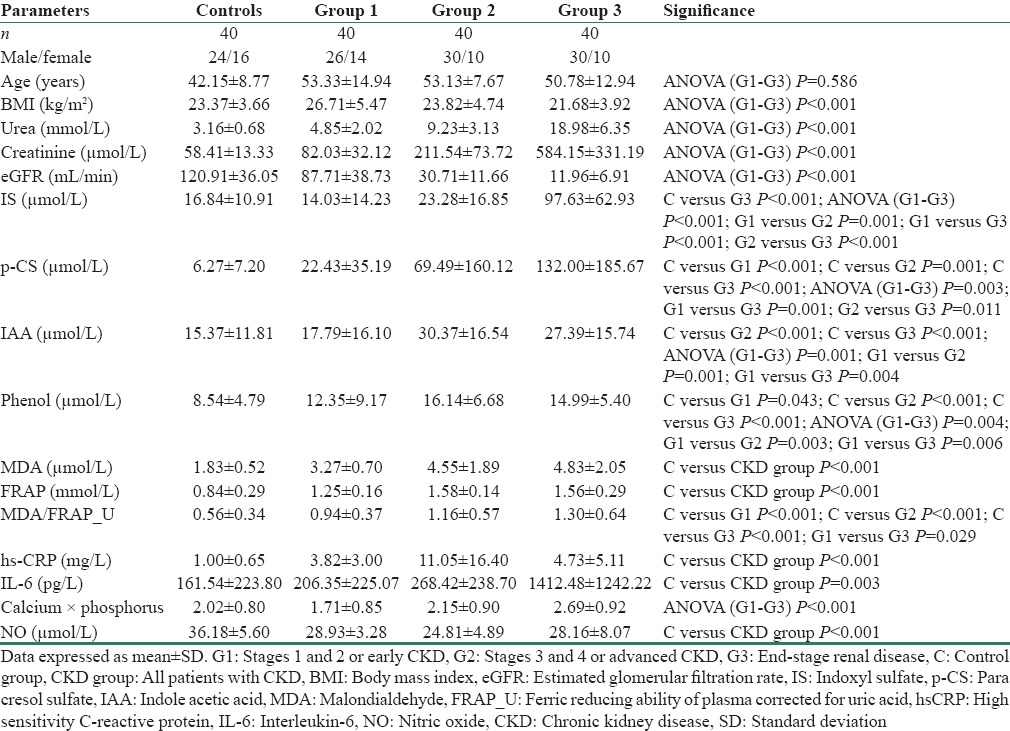

Demographic data and the biochemical parameters studied are presented in Table 1. The scatterplots showing the distribution of GDUT are shown in Figure 1. There was an increase in all the GDUT across the three groups of CKD. Plasma levels of IS and p-CS were increasing with progression of CKD. The increase found in IS, IAA, and phenol was earlier to p-CS. All patients with CKD had significantly higher levels of MDA, FRAP, hsCRP, IL-6, and calculated comprehensive score (P < 0.001) compared to controls. NO levels showed a significant decrease (P < 0.001) compared to controls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and biochemical markers studied in controls and chronic kidney disease patients

Figure 1.

Scatterplots showing the distribution of gut-derived uremic toxins

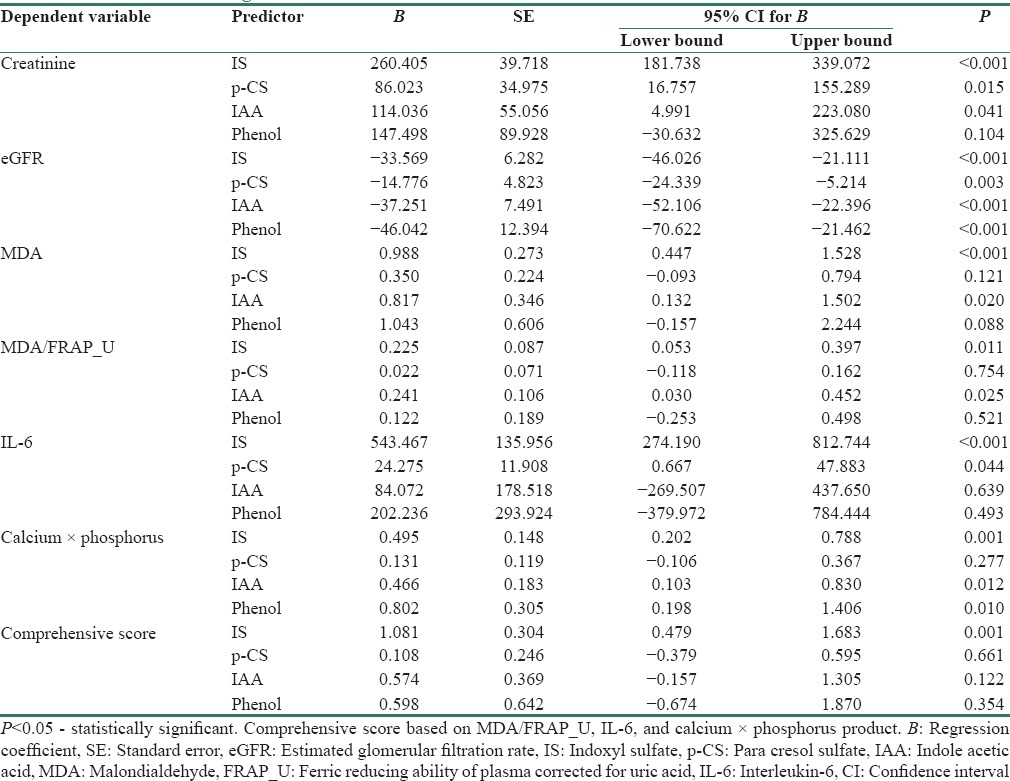

The association of GDUT with renal function and CVD risk factors is shown in Table 2. All the four uremic toxins showed significant negative association with eGFR. IS and IAA showed significant positive association with MDA and MDA/FRAP_U. IS and p-CS showed significant positive association with IL-6. IS, IAA, and phenol showed a significant positive association with Ca × P product. Only IS showed a positive association with the comprehensive score, indicating its involvement in all the three pathophysiological factors studied.

Table 2.

Association of gut-derived uremic toxins with renal function and cardiovascular disease risk factors

Discussion

Uremic toxins have been identified to be important links in the causation of accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with CKD.[12] GDUT have come to particular focus with the development of strategies to reduce intestinal absorption of these toxins. In the present study, all the GDUT studied, i.e., IS, p-CS, IAA, and phenol, were found to be higher in CKD patients (P = 0.009 for IS, P < 0.001 for p-CS and phenol, P = 0.001 for IAA) compared to controls. The levels of these toxins also increased progressively with increasing stage of CKD (IS: P < 0.001; p-CS: P = 0.003; IAA: P = 0.001; phenol: P = 0.004). However, except for IS which showed a continuous increase, other GDUT studied did not show further increase after Group 2 CKD [Figure 1]. Similar increase was reported for IS,[13,14] p-CS,[14,15] IAA,[16] and phenol.[17] The mechanisms proposed for increased generation of GDUT include decreased absorption of amino acids resulting in availability of substrate for metabolism by microbes, alteration of gut flora in favor of proteolytic microorganisms producing more toxin precursors, abnormal intestinal motility resulting in increased absorption of bacterial toxins along with decreased renal clearance.[18]

Association of gut-derived uremic toxin with renal function

All four GDUT studied except phenol showed significant positive association with creatinine, whereas all showed negative association with eGFR [Table 2]. Meijers et al.[19] showed significant positive correlation between total IS and creatinine but not with p-CS, whereas Lin et al.[20] observed significant positive correlation with both IS and p-CS. Liabeuf et al.[15] and Barreto et al.[13] reported significant inverse association of GFR with p-CS and IS, respectively. These and our findings suggest decreased clearance as one of the reasons for accumulation of GDUT.

Gut-derived uremic toxins and oxidative stress

Both OS markers studied, MDA and FRAP were found to be elevated in patients with CKD (P < 0.001) as compared to controls. Similar findings were reported in other studies.[21,22] About 60% of the total antioxidant power measured by FRAP assay is contributed by uric acid.[23] Hence, FRAP_U and MDA/FRAP_U were considered as the combined effect of oxygen radical production and nonenzymatic antioxidant defense. MDA/FRAP_U was significantly higher in CKD patients (P < 0.001) compared to controls, indicating increased production of oxygen-free radicals as the main reason for OS in CKD. Among the GDUT studied, IS and IAA showed positive association with MDA (P < 0.001 and 0.020 for IS and IAA, respectively) as well as with MDA/FRAP_U (P = 0.011 and 0.025 for IS and IAA, respectively). These results suggest that the OS in CKD is predominantly due to overproduction of oxygen-free radicals and IS and IAA contribute to the increased production of oxygen radicals.

Rossi et al.[24] reported that free IS and p-CS were associated with glutathione peroxidase in patients with stages 3 and 4 CKD. Chao and Chiang[25] reported that uremic toxins are potent inducers of OS and contribute to tissue damage. Studies involving animal models showed that upregulation of cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2), a source of renal reactive oxygen species (ROS) through nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) dependent or independent pathways, may induce OS.[25,26] IAA was shown to increase COX-2 levels, thereby contributing to ROS generation.[16] Dou et al.[27] showed that IS significantly increased ROS production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells through activation of NADPH oxidase. They also observed that both oxidized and reduced forms of glutathione were inhibited by IS.

Gut-derived uremic toxins and Inflammation

CKD has been reported to be associated with inflammation. In the present study, both the inflammatory markers studied, hsCRP and IL-6, were elevated in CKD patients when compared with controls (P < 0.001). The rise in hsCRP occurred early in CKD and there was no further increase with progression of the disease. However, IL-6 showed a continuous increase with progression of CKD (P < 0.001). Among the GDUT studied, IS (P < 0.001) and p-CS (P = 0.044) showed significant positive association with IL-6. Thus, findings of the present study show that GDUT mainly IS and p-CS have a pro-inflammatory effect.

The increase in the levels of inflammatory markers in CKD patients could be due to their decreased renal clearance and other coexisting factors.[28] Rossi et al.[24] found that IS and p-CS correlated significantly with IL-6 in stages 3 and 4 CKD patients. Dou et al.[16] found significant positive correlation between IAA and CRP. Accumulated IS is shown to cause injury to tubular cells and induce leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells through endothelial cell inflammation.[29,30] In experimental models, p-CS promoted expression of inflammatory genes and contributed to renal cell injury.[31] However, some studies found no significant association between uremic toxins and hsCRP.[25] Increased hsCRP levels observed in the present study could be a result of increased synthesis of CRP by liver which is triggered in response to IL-6.[32]

Gut-derived uremic toxins and mineral metabolism

Disturbances in Ca and P metabolism are observed in CKD[33] and GDUT have been identified to contribute to this disturbance in mineral metabolism through causing OS in bone and cardiovascular systems.[34] In the present study, there was an increase in Ca × P product with progressing CKD (P < 0.001). IS, IAA, and phenol showed significant positive association with Ca × P product (P = 0.001, P = 0.012, and P = 0.010, respectively). A previous study has similarly reported a significant positive correlation of p-CS and IS with Ca × P.[35] IS has been shown to be vasculotoxic by promoting aortic calcification.[36]

To understand the influence of GDUT on the pathophysiological factors leading to increased CVD risk associated with CKD, a comprehensive score was calculated. It was observed that CKD patients had higher risk score when compared to controls (5.47 ± 1.99 vs. 2.85 ± 2.26; P < 0.001). IS, which was involved in all the factors, showed positive association with this risk score.

Thus, findings of the present study suggest that GDUT are associated with increased OS, inflammatory state, and bone mineral disturbance. As a result, the increased GDUT levels observed in CKD patients contribute to the increased CVD risk of CKD patients. Hence, treatment in the form of use of pre/probiotics and adsorbent therapies or dietary modifications to reduce the levels of GDUT can be useful in reducing CVD risk in CKD.

Financial support and sponsorship

We thank Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences and Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, Tirupati, for providing financial support under Sri Balaji Arogya Vara Prasadini Scheme (Grant No.: SBAVP-RG/Ph. D/08).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Muntner P, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Chen J, Whelton PK, He J. The prevalence of nontraditional risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:9–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2003;42:1050–65. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102971.85504.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schepers E, Glorieux G, Vanholder R. The gut: The forgotten organ in uremia? Blood Purif. 2010;29:130–6. doi: 10.1159/000245639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moradi H, Sica DA, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Cardiovascular burden associated with uremic toxins in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38:136–48. doi: 10.1159/000351758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccoli GB, Vigotti FN, Leone F, Capizzi I, Daidola G, Cabiddu G, et al. Low-protein diets in CKD: How can we achieve them? A narrative, pragmatic review. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:61–70. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfu125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babu SK, Sivakumar V, Agarwal R, Kumar BS, Solomon A, Kumar A. Serum indoxylsulphate in chronic uraemics. Indian J Nephrol. 1998;8:85–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botev R, Mallié JP, Couchoud C, Schück O, Fauvel JP, Wetzels JF, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate: Cockcroft-Gault and modification of diet in renal disease formulas compared to renal inulin clearance. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:899–906. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05371008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calaf R, Cerini C, Génovésio C, Verhaeghe P, Jourde-Chiche N, Bergé-Lefranc D, et al. Determination of uremic solutes in biological fluids of chronic kidney disease patients by HPLC assay. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cortas NK, Wakid NW. Determination of inorganic nitrate in serum and urine by a kinetic cadmium-reduction method. Clin Chem. 1990;36(8 Pt 1):1440–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pletinck A, Glorieux G, Schepers E, Cohen G, Gondouin B, Van Landschoot M, et al. Protein-bound uremic toxins stimulate crosstalk between leukocytes and vessel wall. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1981–94. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, Meert N, Glorieux G, Temmar M, et al. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1551–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03980609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi M, Campbell K, Johnson D, Stanton T, Pascoe E, Hawley C, et al. Uraemic toxins and cardiovascular disease across the chronic kidney disease spectrum: An observational study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liabeuf S, Barreto DV, Barreto FC, Meert N, Glorieux G, Schepers E, et al. Free p-cresylsulphate is a predictor of mortality in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1183–91. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dou L, Sallée M, Cerini C, Poitevin S, Gondouin B, Jourde-Chiche N, et al. The cardiovascular effect of the uremic solute indole-3 acetic acid. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:876–87. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niwa T. Phenol and p-cresol accumulated in uremic serum measured by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Clin Chem. 1993;39:108–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanholder R, Glorieux G. The intestine and the kidneys: A bad marriage can be hazardous. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:168–79. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meijers BK, De Loor H, Bammens B, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P. p-Cresyl sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1932–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02940509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CJ, Chen HH, Pan CF, Chuang CK, Wang TJ, Sun FJ, et al. p-Cresylsulfate and indoxyl sulfate level at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 2011;25:191–7. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durak I, Kaçmaz M, Elgün S, Oztürk HS. Oxidative stress in patients with chronic renal failure: Effects of hemodialysis. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:84–7. doi: 10.1159/000075634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdogan C, Unlüçerçi Y, Türkmen A, Kuru A, Cetin O, Bekpinar S. The evaluation of oxidative stress in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;322:157–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi M, Campbell KL, Johnson DW, Stanton T, Vesey DA, Coombes JS, et al. Protein-bound uremic toxins, inflammation and oxidative stress: A cross-sectional study in stage 3-4 chronic kidney disease. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao CT, Chiang CK. Uremic toxins, oxidative stress, and renal fibrosis: An interwined complex. J Ren Nutr. 2015;25:155–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai Y, Sigala W, Adams GR, Vaziri ND. Effect of exercise on cardiac tissue oxidative and inflammatory mediators in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2009;29:213–21. doi: 10.1159/000156715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dou L, Jourde-Chiche N, Faure V, Cerini C, Berland Y, Dignat-George F, et al. The uremic solute indoxyl sulfate induces oxidative stress in endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1302–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu HJ, Yen CH, Wu IW, Hsu KH, Chen CK, Sun CY, et al. The association of uremic toxins and inflammation in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niwa T. Uremic toxicity of indoxyl sulfate. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2010;72:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito S, Osaka M, Higuchi Y, Nishijima F, Ishii H, Yoshida M. Indoxyl sulfate induces leukocyte-endothelial interactions through up-regulation of E-selectin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38869–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poveda J, Sanchez-Niño MD, Glorieux G, Sanz AB, Egido J, Vanholder R, et al. p-cresyl sulphate has pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic actions on human proximal tubular epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:56–64. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surekha RH, Madhavi G, Srikhant BM, Jharna P, Rao UR. Serum ADA and C-reactive protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Hum Genet. 2006;6:195–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lekawanvijit S, Kompa AR, Wang BH, Kelly DJ, Krum H. Cardiorenal syndrome: The emerging role of protein-bound uremic toxins. Circ Res. 2012;111:1470–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.278457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka H, Komaba H, Koizumi M, Kakuta T, Fukagawa M. Role of uremic toxins and oxidative stress in the development of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:98–101. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu IW, Hsu KH, Lee CC, Sun CY, Hsu HJ, Tsai CJ, et al. p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:938–47. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adijiang A, Goto S, Uramoto S, Nishijima F, Niwa T. Indoxyl sulphate promotes aortic calcification with expression of osteoblast-specific proteins in hypertensive rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1892–901. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]