Abstract

Nucleic-acid-related events in the HIV-1 replication cycle are mediated by nucleocapsid, a small protein comprising two zinc knuckles connected by a short flexible linker and flanked by disordered termini. Combining experimental NMR residual dipolar couplings, solution X-ray scattering and protein engineering with ensemble simulated annealing, we obtain a quantitative description of the configurational space sampled by the two zinc knuckles, the linker and disordered termini in the absence of nucleic acids. We first compute the conformational ensemble (with an optimal size of three members) of an engineered nucleocapsid construct lacking the N- and C-termini that satisfies the experimental restraints, and then validate this ensemble, as well as characterize the disordered termini, using the experimental data from the full-length nucleocapsid construct. The experimental and computational strategy is generally applicable to multidomain proteins. Differential flexibility within the linker results in asymmetric motion of the zinc knuckles which may explain their functionally distinct roles despite high sequence identity. One of the configurations (populated at a level of ≈40%) closely resembles that observed in various ligand-bound forms, providing evidence for conformational selection and a mechanistic link between protein dynamics and function.

Keywords: HIV-1, nuclear magnetic resonance, nucleocapsid, protein engineering, X-ray scattering

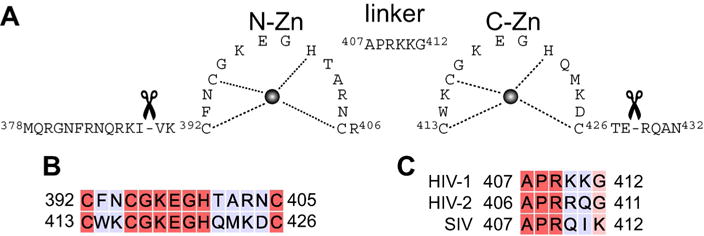

The human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) nucleocapsid protein plays a critical role in various stages of the HIV-1 replication cycle including viral genome recognition and packaging, immature virion assembly and reverse transcription.[1] Nucleocapsid is a 55-residue polypeptide, one of the smallest constituents of the Gag precursor polyprotein, comprising two highly conserved zinc (Zn) knuckles that are separated by a basic linker (407APRKKG412; numbering based on Gag polyprotein precursor from strain HXB2) and flanked by disordered N- and C-termini (Figure 1A). Both Zn knuckles—N-Zn and C-Zn—are characterized by a C-X2-C-X4-H-X4-C motif. Despite their high (≈57%) sequence identity (Figure 1B), the two Zn knuckles are functionally distinct,[2] and enable nucleocapsid to interact with almost any nucleic acid, albeit with different specificity. Nucleocapsid binds to single stranded RNA with very high affinity culminating in selective packaging of the viral genome, and drives nucleic acids into thermodynamically stable conformations, a vital prerequisite for reverse transcription.[3] The exact mechanism for this chaperone activity is unclear, but is thought to involve entropy exchange[4] whereby binding to nucleic acids is coupled to a structural transition in nucleocapsid and partial melting of the oligonucleotide, allowing the oligonucleotide to sample multiple conformations, eventually resulting in a stable protein-nucleic acid complex.

Figure 1.

Domain organization of HIV-1 nucleocapsid. A) Nucleocapsid constructs used in the current work: full-length (residues 378–432) includes the N- and C-terminal tails, while the tails have been removed in the truncated version (residues 390–428). Residue numbering is based on the full-length Gag polyprotein precursor from HIV-1 strain HXB2. B) Sequence comparison of the N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles. C) Sequence comparison of the linker from HIV-1, HIV-2 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV).[5]

The functional versatility of nucleocapsid relies upon plasticity in the spatial orientation of the two Zn knuckles, a quantitative description of which would provide a deeper mechanistic understanding of nucleocapsid function. Several structures of intact nucleocapsid have been solved by NMR in the presence of nucleic acids which lock the two Zn knuckles into a single configuration.[6,7] In the absence of nucleic acids, however, 15N relaxation data indicate significant motion between the two knuckles, precluding crystallization, and the few, observed weak inter-knuckle nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOE) are inconsistent with a single structure.[8] Moreover, both the N- and the C-termini, which constitute significant portions of nucleocapsid, are unstructured in the absence of nucleic acids, further complicating structural characterization. In such cases integrating NMR-derived residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) with small angle solution X-ray scattering (SAXS) can be used to generate conformational ensembles that accurately describe the accessible conformational space.[9] This is because RDCs acquired using a steric alignment medium, such as neutral bicelles, provide orientational information on bond vectors relative to an external alignment tensor whose elements (magnitude and orientation) can be directly calculated from molecular shape (derived from the coordinates) using a steric obstruction model.[9,10] SAXS provides complementary information on overall molecular size and shape. Combining these two different sets of experimental data is necessary to remove their respective intrinsic ambiguities. Here we make use of a novel simulated annealing approach driven by RDC and SAXS data acquired on two engineered nucleocapsid constructs—full length (residues 378–432) and truncated (residues 390–428), where the latter lacks the disordered N- and C-termini of the former (Figure 1A), to obtain a quantitative description of the configurational space sampled by the two Zn-knuckles relative to one another, as well as the disposition of the disordered tails.

Comparison of 1HN/15N chemical shifts of full-length and truncated nucleocapsid, acquired under identical experimental conditions, reveal only a few perturbations—specifically for Glu398 and Gly399 in the N-Zn knuckle and Lys415 in the C-Zn knuckle, primarily due to interactions between the disordered termini and surface exposed regions of the knuckles (Supporting Information, Figure S1 A). The 1HN/15N chemical shifts for the linker residues (407APRKKG412) connecting the N-and C-Zn knuckles are virtually identical for the two constructs indicating that the conformational and dynamic properties of the linker remain unchanged.

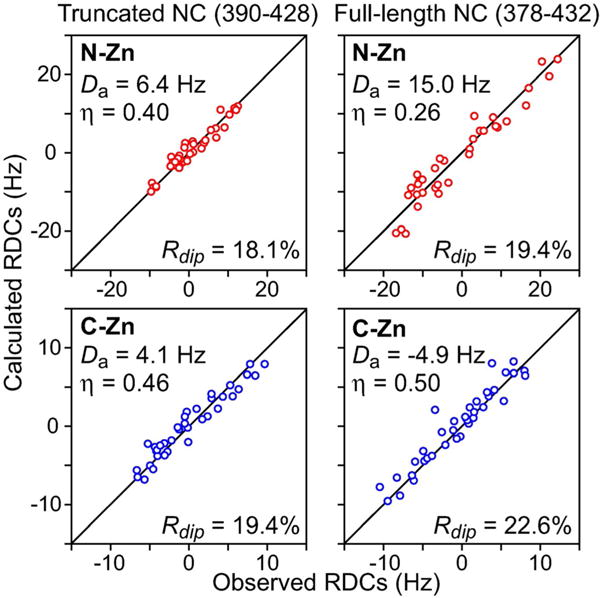

The structures of the knuckles are unaffected by the presence or absence of the disordered termini as the RDCs of the individual knuckles (measured in neutral lipid bicelles) display excellent agreement to those calculated from the coordinates of the respective knuckles taken from the NMR structure of a nucleocapsid–inhibitor complex (PDB 2M3Z)[11] with RDC R-factors[13] less than 25% (Figure 2). Moreover, the magnitude (Da) and rhombicity (η) of the alignment tensors calculated for the N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles are different from one another (especially evident for the full-length construct; cf. right panels in Figure 2), indicating that the two knuckles align (and therefore tumble) semi-independently of one another.[14] Although the RDCs for the full-length and truncated constructs are correlated to one another, the correlation is poor (ρ=0.83 and 0.75 for N-Zn and C-Zn, respectively; Supporting Information Figure S1 B) as the presence of disordered tails alters the overall shape of the conformational ensemble sampled by nucleocapsid resulting in different alignment tensors.

Figure 2.

Backbone RDC analysis of truncated and full-length nucleocapsid (NC) constructs (left and right panels, respectively). Panels show the best-fit agreements from singular value decomposition (SVD) between backbone (N-H, N-C′ and Cα-C′) RDCs measured in 5% lipid bicelles and those calculated from coordinates of the individual N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles taken from the NMR structure of a nucleocapsid–inhibitor complex (PDB ID 2M3Z).[11] Cα-C′ and N-C′ RDCs were normalized relative to the N-H RDCs by scaling them by factors of 5.05 and 8.33, respectively, based on bond lengths and gyromagnetic ratios.[12] The data for the N-Zn (residues 392–406) and C-Zn (residues 413–426) knuckles are depicted in red and blue, respectively. The RDC R-factor, Rdip, is given by {<(Dobs–Dcalc)2>/(2<Dobs2>)}1/2, where Dobs and Dcalc are the observed and calculated RDC values, respectively.[13] Da and η are the magnitude (normalized to the N-H RDCs) and rhombicity, respectively, of the alignment tensor obtained by SVD.

As the useful residue-specific experimental data for the disordered N- and C-terminal tails are limited to RDCs, we used a two-stage calculation strategy. Specifically, RDC and SAXS-driven ensemble simulated annealing was used to first characterize the conformational space sampled by the N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles in the truncated nucleocapsid construct lacking the tails. Subsequently, the full-length construct was used to validate the conformational ensemble obtained for the truncated construct and to characterize the conformational space sampled by the tails. Full details of the calculation strategy using Xplor-NIH[15] is provided in the Supporting Information.

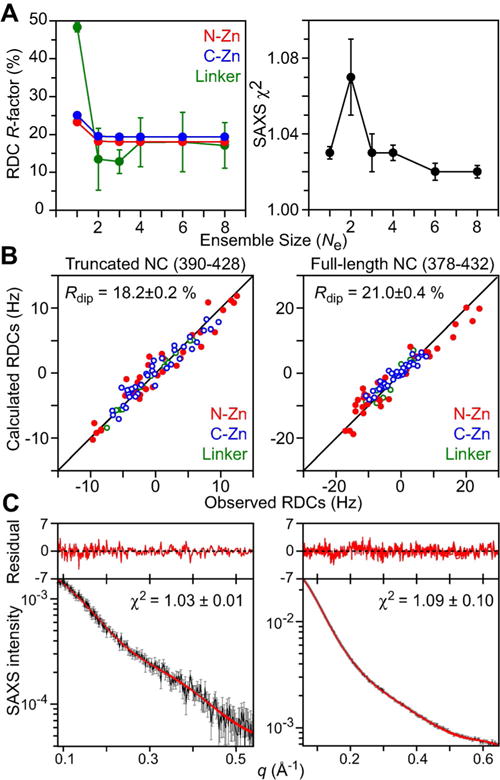

The initial coordinates for the simulated annealing calculations were taken from PDB 2M3Z.[11] The N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles were treated as rigid bodies while the linker (residues 407–412) was given all degrees of freedom. Calculations were carried out with ensemble sizes Ne ranging from one to eight, and the population weights of the ensemble members were optimized during the course of simulated annealing (Figure 3A). While a Ne=1 ensemble can account for the SAXS data, it fails to account satisfactorily for the RDC data. The optimal ensemble size for which both RDC R-factors for the N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles reach their target values (from the SVD fits to the individual Zn knuckles; cf. Figure 2) and the SAXS χ2 approaches a value of one, is Ne=3. Agreement between observed and calculated RDC and SAXS data for the Ne=3 truncated ensemble is shown in the left panels of Figures 3B and C, respectively, and the results are summarized in Table 1. The Ne=3 ensemble is characterized by two major, approximately equally populated, clusters (pcluster1≈0.40; pcluster2≈0.50) and one minor cluster (pcluster3 ≈0.10) which are best visualized when the ensembles are fit to the C-Zn knuckle (Figure 4A). Since only a single set of 1HN/15N cross-peaks is observed, interconversion between the three states is fast on the chemical shift time scale (i.e. sub-millisecond).

Figure 3.

RDC- and SAXS-driven ensemble-simulated annealing calculations for truncated and full-length nucleocapsid (NC) constructs. A) RDC R-factors and SAXS χ2 as a function of ensemble size, Ne, for the truncated construct. Note that the increase in the SAXS χ2 for Ne=2 simply indicates that there is conflict between the RDC and SAXS data at Ne=2 that is resolved for Ne ≥ 3. B) Agreement between observed and calculated RDCs for truncated (left) and full-length (right) NC ensembles. C) Agreement between observed and calculated SAXS curves for truncated (left) and full-length (right) NC ensembles. The experimental SAXS data are shown in black with gray vertical bars equal to ±1 standard deviation, and the calculated curves for the ten (truncated) and seven (full-length) lowest energy ensembles are shown in red. The residuals, given by (Iicalc–Iiobs)/Iierr, are plotted above the curves.

Table 1.

Structural statistics for the Ne=3 ensemble obtained from RDC and SAXS-driven simulated annealing.[a]

| Truncated NC (residues 390–428) |

Full-length NC (residues 378–432) |

|

|---|---|---|

| RDC R-factors [%][b] | ||

| N-Zn (37/34)[c] | 18.1±0.03 | 20.3±0.2 |

| C-Zn (37/37)[c] | 19.4±0.06 | 26.4±1.5 |

| Linker (13/11)[c] | 12.8±3.1 | 35.5±3.0 |

| N-terminal tail (−/11) | – | 9.8±0.6 |

| C-terminal tail (−/12) | – | 26.0±2.9 |

| Overall (87/105) | 18.2±0.2 | 21.0±0.4 |

| SAXS χ2 | 1.03±0.01 | 1.09±0.10 |

For truncated nucleocapsid, values are reported for the ten lowest energy Ne=3 ensembles. These ten ensembles were used to generate the full-length nucleocapsid ensembles (Ne=3×5, with five copies of the tails per ensemble member; see text and Supporting Information), where only the tails are allowed to move during simulated annealing (i.e. the knuckles and linker are treated as single rigid bodies held fixed to the configurations obtained from the truncated construct calculations). The values reported for the full-length nucleocapsid represent the averages for seven of the ten ensembles, as three of the ensembles showed significant deviations between observed and calculated N-C′ and/or Cα-C′ RDCs for Arg 409 within the linker (see text).

The RDCs comprise backbone N-H, N-C′ and Cα-C′ RDCs. In calculating the RDC R-factors,[13] all RDCs are normalized relative to the N-H RDCs (see Figure 2, caption). The numbers of RDCs are given in parentheses, with the first and second numbers relating to the truncated and full-length nucleocapsid (NC) constructs. At each step of simulated annealing refinement, the RDC alignment tensor of each ensemble member is calculated in Xplor-NIH[15] directly from its overall molecular shape (derived from the molecular coordinates) using a steric obstruction model.[9,10]

The N-Zn, C-Zn and linker comprise residues 392–406, 413–426 and 407–412, respectively. The target RDC R-factors for the N-Zn and C-Zn knuckles, obtained by SVD fitting[15b] against the individual knuckle template coordinates (PDB 1M3Z),[11] are 18.1 and 19.4%, respectively, for the truncated construct, and 19.4 and 22.6%, respectively, for the full-length construct.

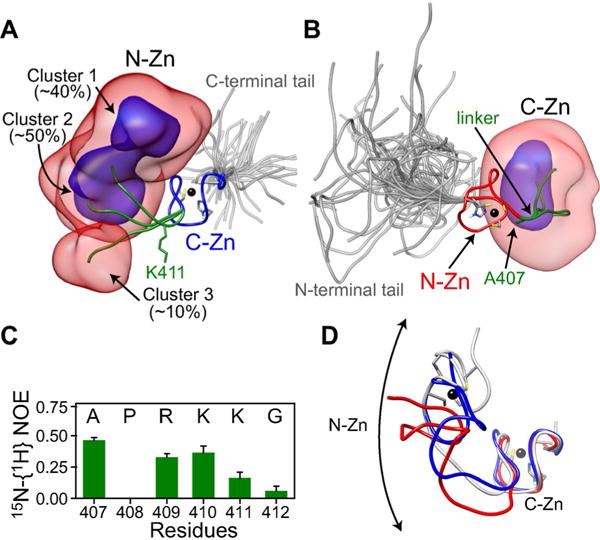

Figure 4.

Three-member ensemble of full-length unliganded nucleocapsid derived from RDC and SAXS-driven simulated annealing. Overall distribution of: A) the N-Zn knuckle when best-fitting to the C-Zn knuckle and B) the C-Zn knuckle when best-fitting to the N-Zn knuckle, displayed as reweighted atomic probability maps[16] plotted at 10% (semi-transparent red) and 50% (blue) of maximum, and calculated from the seven lowest energy Ne=3 ensembles. Representative structures from the three clusters are shown as ribbon diagrams with the N-Zn in red, the C-Zn in blue, the linker in green, and the tails in gray (for each ensemble member within the Ne=3 ensemble, the tails are represented by a five-member sub-ensemble). Zinc atoms are depicted by black spheres. A few residues including those that coordinate the zinc atoms are also shown. C) 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE data for linker residues in the context of full-length nucleocapsid (data were recorded in the absence of nucleic acids at 35 °C and a 1H frequency of 500 MHz.) D) Comparison of the cluster 1 conformation (gray) with the ligand-bound conformations observed in structures of nucleocapsid-DNA (blue, PDB 2EXF)[6c] and RNA (red, PDB 1F6U)[6b] complexes. For the sake of clarity, the nucleic acids are not shown.

The results obtained for the truncated nucleocapsid were validated against the RDC and SAXS data for full-length nucleocapsid as follows. The ten lowest energy Ne=3 ensembles for the truncated nucleocapsid were used as starting coordinates with the disordered N- and C-terminal tails added to the coordinates. For each ensemble member, the tails were represented by a five-member sub-ensemble. The knuckles and linker for each ensemble member were held fixed in the configuration obtained from the calculations with the truncated construct, while only the tails were allowed to move (in torsion space) subject to RDC and SAXS-driven simulated annealing. Seven of the ten resulting ensembles satisfy both the RDC and SAXS data within experimental error for the full-length nucleocapsid, including the RDCs within the tails (Figures 3B and 3C, right panels, and Table 1). Three of the full-length ensembles, however, showed significant deviations for the N-C′ and/or Cα-C′ RDCs of Arg 409 (the third residue of the linker) due to very subtle changes in the distribution of the ϕ/ψ ensemble for this residue (see Supporting Information Figure S2), illustrating the discriminating power of cross-validation against the full-length nucleocapsid data. Note also how the two-fold increase in the span of the RDCs for the N-Zn (≈ ±20 Hz) versus C-Zn (≈ ±10 Hz) knuckle of the full-length nucleocapsid is faithfully reproduced. The origin of this effect lies in the impact of the longer N-terminal tail (12 residues) relative to the shorter C-terminal one (4 residues) on the alignment of the respective adjacent Zn-knuckles.

Reweighted atomic probability maps[16] generated from the seven lowest energy full-length nucleocapsid ensembles are shown in Figure 4, and depict the positional distributions of the N- and C-Zn of nucleocapsid relative to one another. While the overall configurational space sampled by the full-length nucleocapsid is large, the conformational distribution of the N-Zn is clearly distinct from that of the C-Zn as a result of differential flexibility along the linker region, with increased conformational flexibility from the N- to the C-terminal end of the linker. Thus, the three clusters are clearly visualized when best-fitting to the C-Zn knuckle where the N-Zn knuckle exhibits a boomerang-like distribution (Figure 4A), but not when best-fitting to the N-Zn knuckle (Figure 4B).

Examination of the ϕ/ψ backbone torsion angles for the linker residues reveal that interconversion between the three configurational states involves changes in ϕ/ψ angles within the most favorable regions of Ramachandran space (Supporting Information, Figure S2). For Ala 407, Pro 408, Arg 409 and Lys410, the variations in ϕ/ψ are relatively minor, occur within the β-region and therefore involve minimal energy barriers. Likewise, the larger variation in ϕZ/ψ space sampled by Gly 412 involves contiguous low energy regions. For Lys411, however, significant barriers have to be overcome since hops between β, α-helix and possibly left-handed helix regions are observed. The larger ϕ/ψ space sampled by Lys411 and Gly 412 is fully consistent with their smaller (0 to 0.1) heteronuclear 15N-{1H} NOE values compared to those for Ala 407 (0.46), Arg 409 (0.33) and Lys410 (0.36) (Figure 4C), in agreement with previous NMR relaxation data.[8e] Interestingly, the residues at either end of the linker, Pro 408 and Gly 412, are highly (≥99%) conserved in all HIV-1 strains,[5] and further, Pro 408 and Arg 409 are completely conserved in HIV-1, HIV-2 and SIV (Figure 1C). Moreover, mutational analysis of linker residues indicate that both Pro 408 and Arg 409 are essential for HIV-1 replication[17] which would support the functional importance of Pro408 in limiting the conformational flexibility at the N-terminal end of the linker.

There are inter-knuckle contacts ≤ 4 Å in Clusters 1 and 2, but none in Cluster 3 (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Those in cluster 1 are fully consistent with the previously observed weak inter-knuckle 1H-1H NOEs.[8d,e] All three clusters exhibit contacts ≤ 4 Å between Asn393 of the N-Zn knuckle and residues within the linker, also consistent with previously reported NOE data.[8e] The majority of residues involved in inter-knuckle and knuckle-linker contacts are highly conserved throughout all HIV-1 strains (Supporting Information, Figure S3).

Comparison of the three spatial configurations of the Zn-knuckles of free nucleocapsid with that observed in ligand-bound forms complexed to either DNA[6c] or RNA[6b] indicate that cluster 1 is closest to the ligand-bound conformation (Figure 4D). Thus, ligand binding involves a degree of conformational selection in which a configuration close, but not necessarily identical, to the final ligand-bound form is preferentially recognized by the ligand.

It is tempting to speculate from the current structural and dynamic data that differential flexibility of the residues within the linker connecting the N- and C-Zn knuckles of nucleocapsid may play an important role in the functional diversity of nucleocapsid. For example, the binding specificity of nucleocapsid is dependent upon the oligomerization state of the Gag precursor, and varies from high affinity towards A-rich mRNA sequences in an assembled immature Gag lattice to GU-rich motifs in cytosol and mature virions, as well as under in vitro conditions.[18]

The coordinates and experimental restraints have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank accession code 5I1R.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Fang (NCI), Zuo (APS) and Seifert (APS) for assistance with SAXS data collection; Drs. Baber, Cai, Garrett, Ghirlando and Tugarinov for discussions. We acknowledge use of the Advanced Photon Source (DOE contract #W-31-109-ENG-38 and PUP-77 agreement between NCI, NIH and Argonne National Laboratory). This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIDDK (to G.M.C.) and CIT (to C.D.S.), and the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the NIH (to G.M.C.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this article can be found under: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201600212.

References

- 1.a) Darlix JL, Godet J, Ivanyi-Nagy R, Fosse P, Mauffret O, Mely Y. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:565–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bell NM, Lever AM. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Gorelick RJ, Chabot DJ, Rein A, Henderson LE, Arthur LO. J Virol. 1993;67:4027–4036. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4027-4036.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tanchou V, Decimo D, Pechoux C, Lener D, Rogemond V, Berthoux L, Ottmann M, Darlix JL. J Virol. 1998;72:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4442-4447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Houzet L, Morichaud Z, Didierlaurent L, Muriaux D, Darlix JL, Mougel M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2311–2319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin JG, Guo J, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;80:217–286. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tompa P, Csermely P. FASEB J. 2004;18:1169–1175. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1584rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak KJ, Starcich B, Josephs SF, Doran ER, Rafalski JA, Whitehorn EA, Baumeister K, et al. Nature. 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) De Guzman RN, Wu ZR, Stalling CC, Pappalardo L, Borer PN, Summers MF. Science. 1998;279:384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Amarasinghe GK, De Guzman RN, Turner RB, Chancellor KJ, Wu ZR, Summers MF. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:491–511. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bourbigot S, Ramalanjaona N, Boudier C, Salgado GF, Roques BP, Mely Y, Bouaziz S, Morellet N. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1112–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Deshmukh L, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:1025–1028. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:1043–1046. [Google Scholar]; b) Deshmukh L, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501985112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Omichinski JG, Clore GM, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Gronenborn AM. FEBS Lett. 1991;292:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80825-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Morellet N, Jullian N, De Rocquigny H, Maigret B, Darlix JL, Roques BP. EMBO J. 1992;11:3059–3065. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Morellet N, de Rocquigny H, Mely Y, Jullian N, Demene H, Ottmann M, Gerard D, Darlix JL, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:287–301. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lee BM, De Guzman RN, Turner BG, Tjandra N, Summers MF. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:633–649. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zargarian L, Tisne C, Barraud P, Xu X, Morellet N, Rene B, Mely Y, Fosse P, Mauffret O. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Deshmukh L, Schwieters CD, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Baber JL, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16133–16147. doi: 10.1021/ja406246z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Venditti V, Schwieters CD, Grishaev A, Clore GM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:11565–11570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515366112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Zweckstetter M, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3791–3792. [Google Scholar]; b) Huang JR, Grzesiek S. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:694–705. doi: 10.1021/ja907974m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goudreau N, Hucke O, Faucher AM, Grand-Maitre C, Lepage O, Bonneau PR, Mason SW, Titolo S. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:1982–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottiger M, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12334–12341. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clore GM, Garrett D. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9008–9012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Braddock DT, Cai M, Baber JL, Huang Y, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8634–8635. doi: 10.1021/ja016234f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Braddock DT, Louis JM, Baber JL, Levens D, Clore GM. Nature. 2002;415:1051–1056. doi: 10.1038/4151051a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schwieters CD, Kuszewski J, Clore GM. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]; c) Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2014;80:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwieters CD, Clore GM. J Biomol NMR. 2002;23:221–225. doi: 10.1023/a:1019875223132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottmann M, Gabus C, Darlix JL. J Virol. 1995;69:1778–1784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1778-1784.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutluay SB, Zang T, Blanco-Melo D, Powell C, Jannain D, Errando M, Bieniasz PD. Cell. 2014;159:1096–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.