Abstract

Background

Vancouver, Canada has a pilot supervised injecting facility (SIF), where individuals can inject pre-obtained drugs under the supervision of medical staff. There has been concern that the program may facilitate ongoing drug use and delay entry into addiction treatment.

Methods

We used Cox regression to examine factors associated with the time to the cessation of injecting, for a minimum of six months, among a random sample of individuals recruited from within the Vancouver SIF. In further analyses, we evaluated the time to enrollment in addiction treatment.

Results

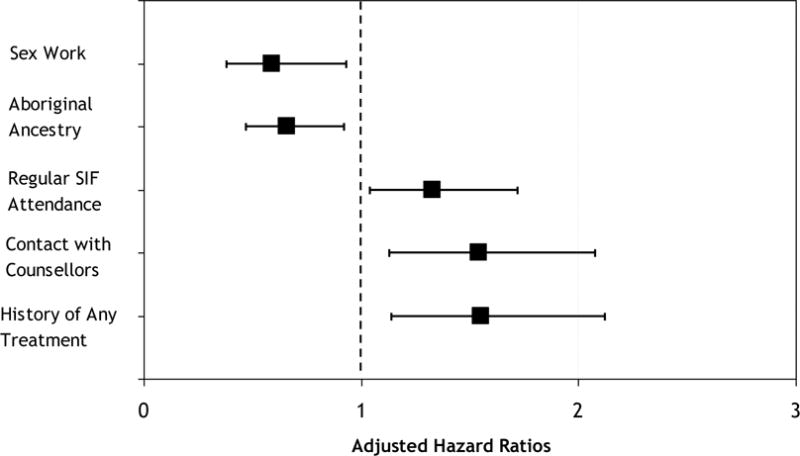

Between December 2003 and June 2006, 1090 participants were recruited. In Cox regression, factors independently associated with drug use cessation included use of methadone maintenance therapy (Adjusted Hazard Ratio [AHR] =1.57 [95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.02–2.40]) and other addiction treatment (AHR =1.85 [95%CI: 1.06–3.24]). In subsequent analyses, factors independently associated with initiation of addiction treatment included: regular SIF use at baseline (AHR =1.33 [95%CI: 1.04–1.72]); having contact with the addiction counselor within the SIF (AHR =1.54 [95%CI: 1.13–2.08]); and Aboriginal ancestry (AHR =0.66 [95%CI: 0.47–0.92]).

Conclusions

While the role of addiction treatment in promoting injection cessation has been well described, these data indicate a potential role of SIF in promoting increased uptake of addiction treatment and subsequent injection cessation. The finding that Aboriginal persons were less likely to enroll in addiction treatment is consistent with prior reports and demonstrates the need for novel and culturally appropriate drug treatment approaches for this population.

Keywords: injection drug use, supervised injection, injection cessation, addiction treatment, Aboriginal ancestry

1. INTRODUCTION

Illicit injection drug use continues to fuel infectious disease and fatal overdose epidemics in many settings, and has prompted substantial community concerns due to public drug use and publicly discarded syringes (Doherty et al., 1997; Garfield and Drucker, 2001; Karon et al., 2001). Public health programming aimed at reducing the harms of injection drug use have been limited, in part, due to the difficulties in reaching people who use injection drugs (IDU) for the purposes of providing addiction treatment services, even when such services are available (Grund et al., 1992; Neaigus et al., 1994).

In an effort to address outstanding public health and public disorder concerns stemming from injection drug use, an increasing number of cities have opened medically supervised safer injection facilities (SIF), where people who use injection drugs can inject pre-obtained illicit drugs under the supervision of health care professionals (Kimber et al., 2003; MSIC Evaluation Committee, 2003; Wood et al., 2004a). Within SIF, individuals are typically provided with sterile injecting equipment and emergency intervention in the event of an accidental overdose, as well as medical care either on site or through referral (Dolan et al., 2000; Wright and Tompkins, 2004). There are now approximately 65 sanctioned supervised drug consumption facilities in operation internationally (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2006).

On September 22, 2003, Vancouver, Canada opened North America’s first government sanctioned SIF (Wood et al., 2004a). Although the opening of the SIF has been associated with reduced public drug use (Wood et al., 2004b), and HIV risk behaviour (Kerr et al., 2005), the program is controversial and there remains concern that it enables drug use and reduces the likelihood that IDU will seek to reduce or quit their illicit drug use (Yamey, 2000; Gandey, 2003; Wood et al., 2004a; Jones, 2006; Wood et al., 2008; International Narcotics Control Board., March 5, 2008).

To examine this question, a number of studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between SIF attendance and engagement with addiction treatment programs. An evaluation of the SIF in Sydney Australia, demonstrated that individuals who frequently used the facility were more likely to be referred to drug treatment than other clients (Kimber et al., 2008). In Vancouver, an earlier analysis found that frequent use of the SIF and contact with addictions counsellors at the facility were both independently associated with increased entry into medical detoxification, and that entry into detoxification spurred entry into other treatments (Wood et al., 2006). Another study subsequently found that the SIF opening was independently associated with a 30% increase in detoxification service use among SIF clients (Wood et al., 2007a). Although these analyses imply a positive impact of SIF use on enrolment in detoxification programs, no studies have examined the direct relationship between the use of Vancouver’s SIF and entry into other types of addiction treatment (e.g., residential treatment, methadone maintenance therapy), and more importantly, no studies have evaluated rates of injection cessation among SIF clients. The present study was conducted to examine factors associated with drug use cessation among IDU using Vancouver’s SIF, and to examine the potential role of SIF in facilitating injection cessation among this population.

2. METHODS

The Vancouver SIF has been evaluated through the Scientific Evaluation of Supervised Injecting (SEOSI) cohort, which has been described in detail previously (Wood et al., 2004c). Briefly, the cohort was assembled through random recruitment of IDU from within the SIF. Among individuals who were recruited, an interviewer-administered questionnaire was administered at baseline and at semi-annual follow-up visits. Since health service use may be over-reported by IDU (Wood et al., 2004c), the informed consent included a request to perform linkages with administrative health databases. The present study was approved by a Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

2.1. Factors associated with time to cessation of injecting

As previously (Shah et al., 2006; DeBeck et al., 2009), injection cessation was based on self-report and defined as a period of at least six months without any episodes of drug injecting. To assess the potential connection between SIF attendance, participation in addiction treatment, and injection cessation, we began by examining factors potentially associated with the time to cessation of injection drug use. Variables of interest included: age (per 10 years older), number of years injecting illicit drugs (per additional year), gender (female vs. male), Aboriginal ancestry defined as a person who self-reported as being Aboriginal, Métis, Inuit or First Nations (yes vs. no), homelessness defined as having no fixed address (yes vs. no), sex work involvement (yes vs. no), daily cocaine injection (yes vs. no), daily heroin injection (yes vs. no), daily crack cocaine use (yes vs. no), current methadone maintenance use (yes vs. no), and current use of other addiction treatment (excluding methadone) defined as reporting being enrolled in a detoxification program, a recovery house, a residential addiction treatment centre, or engaging with an addictions counselor or participating in peer support programs, i.e., Narcotics Anonymous (yes vs. no). Injection drug use variables were measured at baseline while all other drug use and behavioural variables were time-updated based on each semi-annual follow-up period and, unless otherwise noted, refer to the six month period prior to the interview. Unless otherwise indicated, all variable definitions have been used extensively and were identical to earlier reports (Wood et al., 2005b).

2.2. Factors associated with time to addiction treatment use

After exploring for a potential relationship between engagement with addiction treatment programs and injection cessation, we then assessed whether SIF use was associated with entry into any of these same addiction treatment programs (combined endpoint included all treatment modalities described above). Specifically, we tested whether regular SIF use at baseline (at least one visit per week vs. less than one visit per week as identified through linking to each participant’s record in the SIF database) was associated with time to enrollment in any addiction treatment program. In addition, we recognized that a primary causal mechanism through which IDU could be encouraged to enter other addition treatment programs would be through contact with the addiction counselor who works within the SIF. Therefore, we linked to each participant’s service use history within the SIF database to determine if each participant had met with the addiction counselor before the event or censor date. The other variables of interest considered to be potentially associated with time to entry into addiction treatment programs included any history of engaging in addiction treatment programs, as well as the same socio-demographic and drug use variables included in the previous analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

For both analyses, variables potentially associated with each outcome of interest were modeled in unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression analyses. Here, time zero was the date of recruitment into the study for all participants and the event dates were defined as the date of the first questionnaire at which participants reported either injection cessation in the previous six months or engagement in addiction treatment. In the first analysis participants who remained persistent active injectors were censored as of their last study follow-up or June 2006 whichever came first. Similarly, participants in the second analysis who did not enroll into addiction treatment were censored as of their last study follow-up or June 2006 whichever came first. The multivariate models included all a priori defined variables of interest to adjust for potential confounding. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1. All p-values were two-sided.

3. RESULTS

By June 2006, 6747 unique individuals were registered at the SIF, and between 1 December 2003 and 1 June 2006, 1090 individuals were randomly recruited into SEOSI. Among this group 188 (17%) individuals did not return for a second study visit during our study period and were therefore not included in our statistical analyses. These 188 participants were more likely to younger in age, to have been injecting for fewer years, to be homeless, and less likely to be enrolled in methadone treatment, or any addition treatment program (all p < 0.02). Otherwise, the two groups were similar in terms of all other variables listed in Table 2 (all p >0.05). The baseline characteristics of the remaining 902 participants are presented in Table 1. This sample contributed 3315 observations and the median number of study visits was 3 (IQR= 2–4).

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard analyses of factors associated with time to injection cessation among clients of Vancouver’s supervised injecting facility.

| Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Hazard Ratio | (95% CI)a | Hazard Ratio | (95% CI) |

| Methadone Treatmente | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.56 | (1.03 – 2.36) | 1.57 | (1.02 – 2.40) |

| Other Addiction Treatmente | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.79 | (1.04 – 3.07) | 1.85 | (1.06 – 3.24) |

| Older Age | ||||

| per 10 years older | 1.07 | (0.85 – 1.35) | 0.99 | (0.95 – 1.02) |

| Years Injecting | ||||

| per additional year | 1.01 | (0.99 – 1.03) | 1.01 | (0.98 – 1.04) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female vs. Male | 0.67 | (0.41 – 1.09) | 0.79 | (0.44 – 1.42) |

| Aboriginal Ancestryb | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.83 | (0.48 – 1.42) | 0.94 | (0.54 – 1.64) |

| HomelessC | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.87 | (0.51 – 1.49) | 0.96 | (0.55 – 1.68) |

| Sex WorkC | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.65 | (0.36 – 1.19) | 0.83 | (0.40 – 1.73) |

| Daily Cocaine Injectiond | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.74 | (0.48 – 1.16) | 0.78 | (0.50 – 1.22) |

| Daily Heroin Injectiond | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.62 | (0.41 – 0.95) | 0.69 | (0.44 – 1.06) |

| Daily Crack Cocaine Smokingc | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.75 | (0.50 – 1.14) | 0.90 | (0.59 – 1.38) |

Note:

CI = Confidence Interval;

Aboriginal ancestry was defined as a person who self-reported as being Aboriginal, Métis, Inuit or First Nations;

Denotes activities or situations referring to previous 6 months;

Measured at baseline, referring to 6 months prior to baseline;

Represents current engagement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample at baseline (n=902).

| Characteristic | Median | IQRa |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 39 | 33–45 |

| Yrs Injecting | 17 | 9–26 |

|

| ||

| n | % | |

|

| ||

| Female Gender | 266 | 29 |

| Aboriginal Ancestry | 180 | 20 |

| Homelessb | 167 | 19 |

| Sex Workb | 204 | 23 |

| Daily Cocaine Injectionb | 286 | 32 |

| Daily Heroin Injectionb | 448 | 50 |

| Daily Crack Smokingb | 439 | 49 |

| Regular SIF Useb | 335 | 37 |

| Current Methadone Treatment | 209 | 23 |

| Current Other Treatment (no MT) | 87 | 10 |

| Current Any Treatment | 281 | 31 |

| History of Any Treatment | 746 | 83 |

Note:

Inter Quartile Range;

Denotes activities or situations referring to previous 6 months.

After 24 months of enrollment in the cohort the cumulative incidence of injection cessation was 23.06% (95% Confidence interval CI: [16.2% – 29.9%]). For the analysis of injection cessation 902 participants contributed 2162 observation and there were a total of 95 events of injection cessation. In the unadjusted Cox analysis (see Table 2), factors statistically associated with time to injection cessation were daily heroin injection, methadone maintenance therapy, and use of other addiction treatment. In the adjusted Cox model (see Table 2), factors independently associated with time to injection cessation were methadone maintenance therapy and use of other addiction treatment.

In our analysis of time to entry into addiction treatment, the cumulative incidence of entry into addiction treatment after 24 months of enrolment in the cohort was 57.21% (95% CI: 50.9% – 63.5%). At baseline 281 participants were currently enrolled in some type of addiction treatment. The remaining 621 participants contributed 1234 observations and there were a total of 261 events of entry into addiction treatment. In the unadjusted Cox analysis, factors statistically associated with the time to initiation of addiction treatment included Aboriginal ancestry (HR = 0.65 [95% CI: 0.47 – 0.90]), regular SIF use at baseline (HR = 1.42 [95% CI: 1.11 – 1.81]), any contact with the addiction counselor within the SIF (HR = 1.67 [95% CI: 1.24 – 2.25]), and history of any engagement with addiction treatment (HR = 1.62 [95% CI: 1.19 – 2.20]). In the adjusted Cox model (Figure 1), factors independently and positively associated with the time to initiation of addiction treatment were regular SIF use at baseline (AHR = 1.33 [95% CI: 1.04 – 1.72]), having any contact with the addiction counselor within the SIF (AHR = 1.54 [95% CI: 1.13 – 2.08]), and history of any engagement with addiction treatment (AHR = 1.55 [95% CI: 1.14 – 2.12]); engagement in sex work became significantly negatively associated with initiation of addiction treatment (AHR = 0.59 [95% CI: 0.38 – 0.93]), and Aboriginal ancestry remained negatively associated with time to initiation of addiction treatment after adjustment (AHR = 0.66 [95% CI: 0.47 – 0.92]).

Figure 1. Factors Associated with Time to Enrolment in Addiction Treatment among Clients of Vancouver’s Supervised Injection Facility.

Notes for Figure 1: ‘Regular SIF Attendance’ was measured at baseline and defined as visiting the SIF at least once per week vs. visiting the SIF less than once per week; ‘Contact with Counsellors’ refers to meeting with an addictions councillor at the SIF and was measured through data linkage to the SIF administrative database; ‘History of Any Treatment’ was defined as any history of engaging in any type of addiction treatment programs.

4. DISCUSSION

Among IDU who attended Vancouver’s supervised injecting facility, regular use of the SIF and having contact with counselors at the SIF were associated with entry into addiction treatment, and enrollment in addiction treatment programs was positively associated with injection cessation. Although SIF in other settings have been evaluated based on wide range of outcomes (Dolan et al., 2000; Kimber et al., 2003; MSIC Evaluation Committee, 2003), our study is the first to consider the potential role of SIF in supporting injection cessation. While our study is unique, our findings build on previous international analyses demonstrating a link between SIF attendance and entry into detoxification programs (Wood et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2007a; Kimber et al., 2008).

A postulated benefit of SIF is that, by providing a sanctioned space for illicit drug use, a hidden population of IDU can be drawn into a healthcare setting so that service delivery can be improved. The present study provides additional evidence that SIF appear to promote utilization of addiction services and builds on past evaluations to demonstrate that, through this mechanism, they may also lead to increased injecting cessation. While these findings are encouraging, it is concerning that Aboriginal participants were less likely to enter addiction treatment. This finding is consistent with prior reports (Wood et al., 2005a; Wood et al., 2007b), and highlights the need for innovative and culturally appropriate addiction treatment services developed with full consultation with Aboriginal people who use drugs.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, given that addiction is recognized to be a chronic relapsing condition (Galai et al., 2003; Evans et al., 2009), our definition of injection cessation is restricted to a relatively short period of injection cessation. Nevertheless, our findings are compelling and it is noteworthy that this definition of cessation has been consistently used in the injection drug use literature. Secondly, there are a number of limitations associated with the observational nature of our study. For one, the present study is limited in that the control group included non-frequent SIF users. As has been described previously (Lurie, 1997), selecting adequate control groups is particularly challenging in observational studies examining use of healthcare services for IDU. While a randomized control trial would be an optimal evaluation strategy, interventional study designs to evaluate SIF have been deemed unethical (Christie et al., 2004). Given this limitation it is possible that individuals who are more concerned with their health may be independently more likely to visit a SIF, seek addiction treatment and experience periods of injection cessation. However, previous studies have shown that SIF attract individuals with markers generally associated with lower rates of health-related behaviours (Wood et al., 2005b; Tyndall et al., 2006). Furthermore, although cohort studies can not demonstrate causality, our analyses adjusted for potential confounders, and the present study complements emerging data from several sources that imply SIF can help link IDU to addiction treatment. Nevertheless, the observational nature of our study precludes inferences regarding causation.

There are also a number of limitations associated with some of our measures. Specifically, we do not have information on the level of psychological counselling involved in the various types of addiction treatment, which is a factor that could influence the relationship between addiction treatment and injection cessation. In addition, many of our measures relied on self-report and are susceptible to socially-desirable reporting as well as recall bias. However, we have no reason to suspect that this would be differential based on our outcomes of interest and note that all study participants openly reported injection drug use at baseline. Lastly, it is important to recognize that although our sample is representative of SIF clients in Vancouver, these findings may not be generalizable to other settings.

The present study demonstrates associations between attendance and contact with addiction counselors at SIF, entry into addiction treatment programs, and cessation of injection drug use. Although our observational study can not determine causation, these findings contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting a link between SIF attendance and entry into addiction treatment.

References

- Christie T, Wood E, Schechter M, O’Shaughnessy M. A comparison of the new Federal Guidelines regulating supervised injection site research in Canada and the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Human Subjects. Int J Drug Policy. 2004;15:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Kerr T, Li K, Milloy MJ, Montaner J, Wood E. Incarceration and drug use patterns among a cohort of injection drug users. Addiction. 2009;104:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Junge B, Rathouz PJ, Galai N, Anthony JC, Beilenson P. Discarded needles do not increase soon after the opening of a needle exchange program. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:730–737. doi: 10.1093/aje/145.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K, Kimber J, Fry C, McDonald D, Fitzgerald J, Trautmann F. Drug consumption facilities in Europe and the establishment of supervised injecting centres in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19:337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JL, Hahn JA, Lum PJ, Stein ES, Page K. Predictors of injection drug use cessation and relapse in a prospective cohort of young injection drug users in San Francisco, CA (UFO Study) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galai N, Safaeian M, Vlahov D, Bolotin A, Celentano D. Longitudinal patterns of drug injection behavior in the ALIVE Study Cohort, 1988–2000: description and determinants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:695. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandey A. US slams Canada over Vancouver’s new drug injection site. CMAJ. 2003;169:1063. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield J, Drucker E. Fatal overdose trends in major US cities: 1990–1997. Addiction Research & Theory. 2001;9:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Grund JP, Blanken P, Adriaans NF, Kaplan CD, Barendregt C, Meeuwsen M. Reaching the unreached: targeting hidden IDU populations with clean needles via known user groups. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24:41–47. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2007. 2008 Mar 5; http://www.incb.org/pdf/annual-report/2007/en/annual-report-2007.pdf (Accessed 04/07/2010)

- Jones D. Injection site gets 16-month extension. CMAJ. 2006;175:859. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation. The Report of the Independent Working Group on Drug Consumption Rooms. Joseph Rowntree Foundation; York: 2006. http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/9781859354711.pdf (Accessed 12/12/2009) [Google Scholar]

- Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060–1068. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Tyndall M, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Safer injection facility use and syringe sharing in injection drug users. The Lancet. 2005;366:316–318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J, Dolan K, Van Beek I, Hendrich D, Zurhold H. Drug consumption facilities: an update since 2000. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:227–233. doi: 10.1080/095952301000116951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J, Mattick RP, Kaldor J, van Beek I, Gilmour S, Rance JA. Process and predictors of drug treatment referral and referral uptake at the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:602–612. doi: 10.1080/09595230801995668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie P. Invited commentary: le mystere de Montreal. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:1003–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009227. discussion 1007–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSIC Evaluation Committee. Final report of the evaluation of the Sydney medically supervised injecting centre. 2003 http://www.sydneymsic.com/Bginfo.htm (Accessed 03/27/2010)

- Neaigus A, Friedman SR, Curtis R, Des Jarlais DC, Furst RT, Jose B, Mota P, Stepherson B, Sufian M, Ward T. The relevance of drug injectors’ social and risk networks for understanding and preventing HIV infection. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NG, Galai N, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Longitudinal predictors of injection cessation and subsequent relapse among a cohort of injection drug users in Baltimore, MD, 1988–2000. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall M, Kerr T, Zhang R, King E, Montaner J, Wood E. Attendance, drug use patterns, and referrals made from North America’s first supervised injection facility. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Montaner JS, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Hankins CA, Schechter MT, Tyndall MW. Rationale for evaluating North America’s first medically supervised safer-injecting facility. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004a;4:301–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Marsh D, Montaner J, Tyndall M. Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. CMAJ. 2004b;171:731–734. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Lloyd-Smith E, Buchner C, Marsh D, Montaner J, Tyndall M. Methodology for evaluating Insite: Canada’s first medically supervised safer injection facility for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Journal. 2004c;1 doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Li K, Palepu A, Marsh DC, Schechter MT, Hogg RS, Montaner GJS, Kerr T. Sociodemographic Disparities in Access to Addiction Treatment a Among a Cohort of Vancouver Injection Drug Users. Subst Use Misuse. 2005a;40:1153–1167. doi: 10.1081/JA-200042287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Li K, Lloyd-Smith E, Small W, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Do supervised injecting facilities attract higher-risk injection drug users? Am J Prev Med. 2005b;29:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Stoltz JA, Lai C, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Attendance at supervised injecting facilities and use of detoxification services. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2512–2514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc052939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JS, Li K, Barney L, Tyndall MW, Kerr T. Rate of methadone use among Aboriginal opioid injection drug users. CMAJ. 2007a;177:37. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Rate of detoxification service use and its impact among a cohort of supervised injecting facility users. Addiction. 2007b;102:916–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG. The Canadian government’s treatment of scientific process and evidence: Inside the evaluation of North America’s first supervised injecting facility. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright NM, Tompkins CN. Supervised injecting centres. BMJ. 2004;328:100–102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7431.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamey G. UN condemns Australian plans for “safe injecting rooms”. BMJ. 2000;320:667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]